5.1. Reaction Level

We used questionnaires to measure the reaction level immediately after completion of the training.

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 provide descriptive statistics for the trainees’ reaction level, which included three dimensions: trainer, training delivery and training environment.

The literature confirms the importance of satisfaction with the trainer for achieving effective training [

77]. Findings from this study show that among the three dimensions, namely the trainer, training delivery and training environment, the trainees had the highest level of satisfaction with the trainer, with a weighted average score of 4.076. More than 70 percent of participants reported that they strongly agreed or agreed with all the statements related to aspects of the trainer that were evaluated. A number of studies have highlighted the importance of the quality and efficiency of the trainer and their style if the success of the training programme is to be assured. An effective trainer can be very influential and make a difference in achieving training success [

100,

101] since the trainers play a role in trainees’ learning transfer. Marsh and Overall [

102] found that if a trainee liked their instructor, they were more likely to be satisfied and motivated to do better in the course. Therefore, it is clear that satisfaction with the trainer plays a role in the trainees’ transfer of the skills and knowledge delivered through the training programme [

103]. The trainer, instructor style and human interaction have the strongest effect on trainees’ reactions [

77]. Morgan and Casper [

70] also asserted that the trainer is of high importance in trainees’ overall perceptions of the training. This is consistent with the results of this study, which show that the trainees’ satisfaction with the trainer predicts good reactions of the trainees to training. However, three of the participants believed that the changes after training programmes were not positive: for example, #246 reported that “trainers lack efficiency in skills of presenting the training content and in discussion and dialogue with trainees”, #205 believed that “the training programmes lack sufficient preparation by the trainer” and #174 stated that “trainers in training centres do not have training skills”.

The above results show that, in the current study, the reactions of trainees to the trainer were satisfactory. This shows that the trainers were of a good standard and were chosen well by the training centres. This finding is consistent with the findings of Hassan et al. [

104] and Yusoff et al. [

105] in studies that also indicated that trainees were satisfied with the trainers as they assessed their trainers positively.

Training delivery refers to the training scheduling, the programme length, the training content, the methods of providing training, training equipment and technology resources [

25,

38,

49,

51,

55,

106]. In this study, training delivery ranked second in predicting the satisfaction of the trainees, which indicates its importance and priority in the opinion of the participants. The findings show that the average score for the responses of participants was 3.918, which suggests that the trainees’ opinion of the training delivery was satisfactory.

However, four participants believed that the changes after training programmes were not positive, since only the lecture method was used in the training programmes and they lacked practical application and practice. For instance, #8 believed that “the majority of the training programmes are theoretical and devoid of practice; therefore, they are extremely detached from the practical field and vision of the Ministry of Education”, and #184 reported that “most of the training programmes cannot be implemented practically in the field because they are theoretical”. This corresponds to the finding of Albahussain’s [

107] study, that the most popular training methods used by Arab organisations are seminars, conferences and lectures, and that of Albabtain’s [

108] study, that the methods used in the training of educational leaders in the Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia still depend on the lecture. Studies in the Saudi context have indicated that the reasons for the prevalence of the lecture approach in training programme delivery in Saudi Arabia are the prevailing culture that imposes the method of indoctrination, the conviction of senior management regarding the success of traditional methods of training, such as the lecture approach, and the trainers’ lack of ability to use other approaches [

108,

109].

Although the lecture style is effective in training for many types of tasks and skills [

66], it can be an unengaging and ineffective training delivery method [

110]. Pashiardis [

111] suggested that the most effective training is that which combines different methods, since using multiple methods keeps learners interested, arouses curiosity and leads to enhanced understanding and retention, as individuals learn in different ways. Therefore, using a variety of training methods will increase the likelihood that learners will have been touched by at least one method [

56]. According to Gauld and Miller [

112] and Browne-Ferrigno and Muth [

113], training content should combine theoretical and practical aspects, as well as the transfer of new knowledge and skills, since trainees measure the usefulness of training based on its balance of theoretical and practical content. Similarly, when trainees perceive an imbalance between theoretical and practical training, their satisfaction will generally be low [

14]. Therefore, training centres and trainers must consider the diversity of methods in the implementation of training programmes to achieve greater training effectiveness for trainees. All the elements above suggest that correcting the misconceptions of senior management about the effectiveness of the lecture method and recruiting qualified trainers may address this problem. Trainees’ satisfaction with the training programmes offered to them has also been reported by other studies on training and its evaluation. For example, Chang and Chen [

114] and Yusoff et al. [

105] found that most respondents were satisfied with training delivery and that training programmes were effective.

The training environment is “all about the condition or surrounding of the medium the training programme takes place in” ([

115], p. 34). The training environment is key factors responsible for the successful implementation of a training programme is the training environment [

115]. It includes the suitability of the physical facilities, equipment, classrooms and accommodation [

106,

116]. If the training environment is unsatisfactorily prepared, it will impact on the intake of participants or distract them [

117], which might influence next year’s intake if potential trainees hear bad reports.

In this study, the results indicated that the participants were satisfied with the training environment, as the average response for training environment was 0.902. However, among the elements assessed at the reaction level, the training environment had the lowest level of satisfaction.

The participants were satisfied with all the statements in this section, with the highest satisfaction relating to the statement that the techniques and tools in the training environment were good and appropriate. This may be due to the fact that the training centres do not suffer from a lack of financial resources to equip them, since they are affiliated with the MOE and are especially for training MOE employees, including teachers and head teachers. Therefore, MOE manages and finances them and provides them with full support and the necessary technical resources and tools [

118].

However, one participant (#174) believed that the changes after training were not positive, since the training environment was not clean and was uncomfortable, which negatively affected her attitudes towards the training. The satisfaction of the trainees with the training environment predicts a good reaction to the training, as indicated by the results of this study and other studies. Therefore, if a suitable and comfortable training environment is lacking, this may negatively affect trainees’ attitudes towards the training [

50].

Therefore, it is evident that the training environment positively influences the learning outcomes [

56,

68,

106]. Consequently, the training environment’s role is critical in terms of the emphasis and usefulness of the knowledge gained and the training programme’s success [

119,

120]. This is why the trainees and supervisors highlighted that an inappropriate training environment was one of the barriers to the effectiveness of the training.

The findings on this theme are consistent with those of previous studies [

121] in that the trainees believed that the training environment was satisfactory and that the training environment was important in ensuring participants’ comfort during training.

In summary, trainee female head teachers generally reported satisfaction with the training programmes they received through the training centres in Saudi Arabia. Trainees’ satisfaction with the training included satisfaction with the trainers, the training delivery and the training environment, which reflect the efforts made by the training centres in Saudi Arabia to implement successful training programmes.

However, since the training process is continued every academic year and the programmes vary from one academic year to the next, the training content, method of implementation and trainers differ from one programme to another. This means it is crucial to continue the evaluation process for training programmes to maintain the level of trainees’ satisfaction with training.

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 show to what extent the trainee head teachers had a positive reaction in this first level of Kirkpatrick’s model. The study results showed that trainee female head teachers had positive reactions to and were satisfied with all three dimensions of the training programmes, since each dimension had a mean score greater than 3.60 out of 5.

5.3. Behavioural Level

The behaviour of the trainees was evaluated three months after completion of the training. At this level, the opinions of respondents were investigated using both qualitative and quantitative methods, via questionnaires with open-ended and closed-ended questions.

Table 8 presents the results of the closed-ended questions.

The introductory part of the qualitative investigation included a closed-ended question that examined whether participants felt that their behaviour change was positive after completing the training course or not. Subsequently, a further in-depth investigation was conducted to determine their reasons for choosing a positive or negative response, and the impact of the changes on them and their jobs.

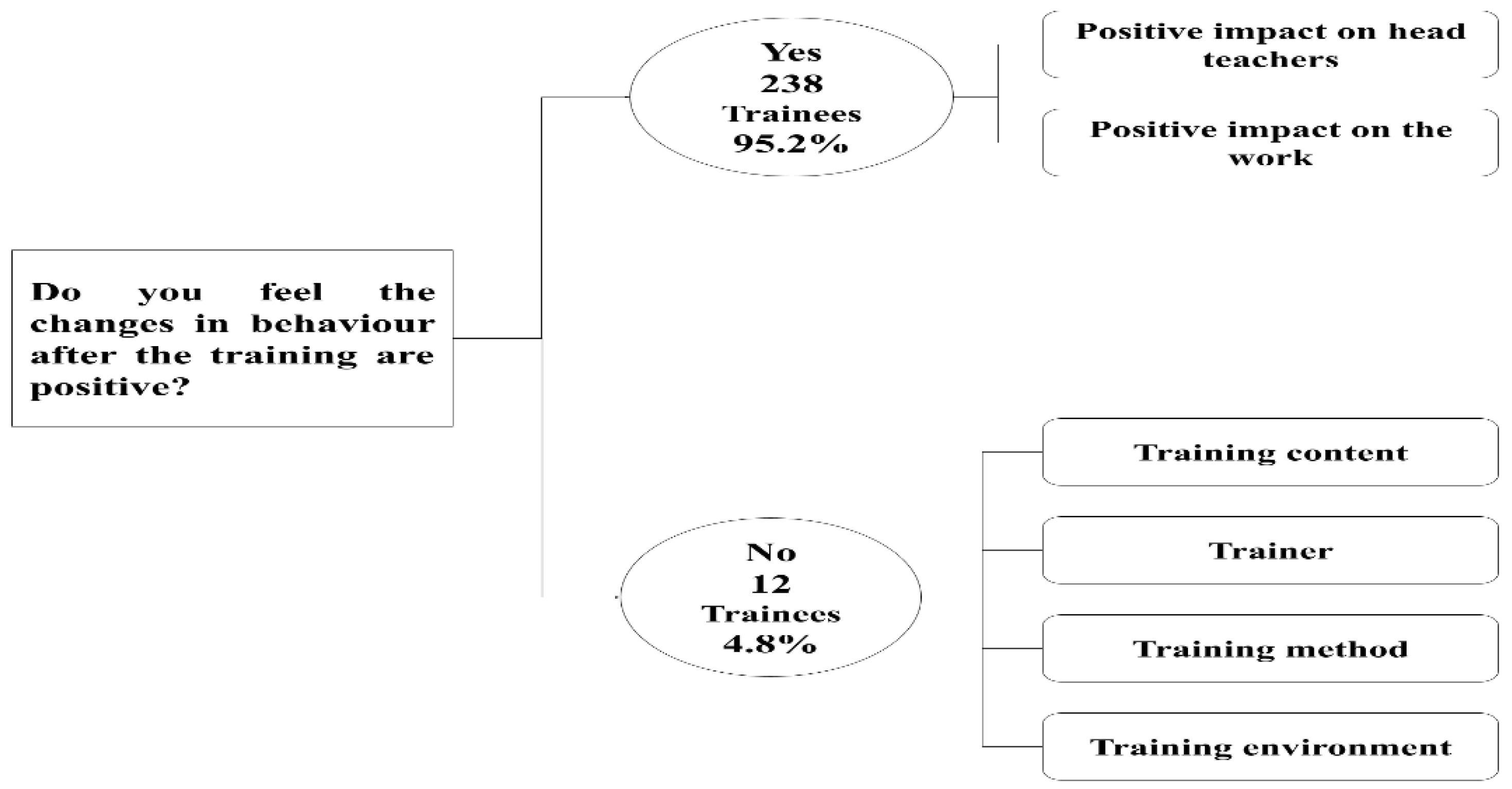

As shown in

Figure 1, 238 participants (95.2 percent) believed that the changes after training were positive, and among the participants who believed that the changes after training were positive, 75 gave reasons for their choice. All the answers were analysed using NVivo Pro 11 software, since there was a large variety of answers. The symbol (N) in front of each value in

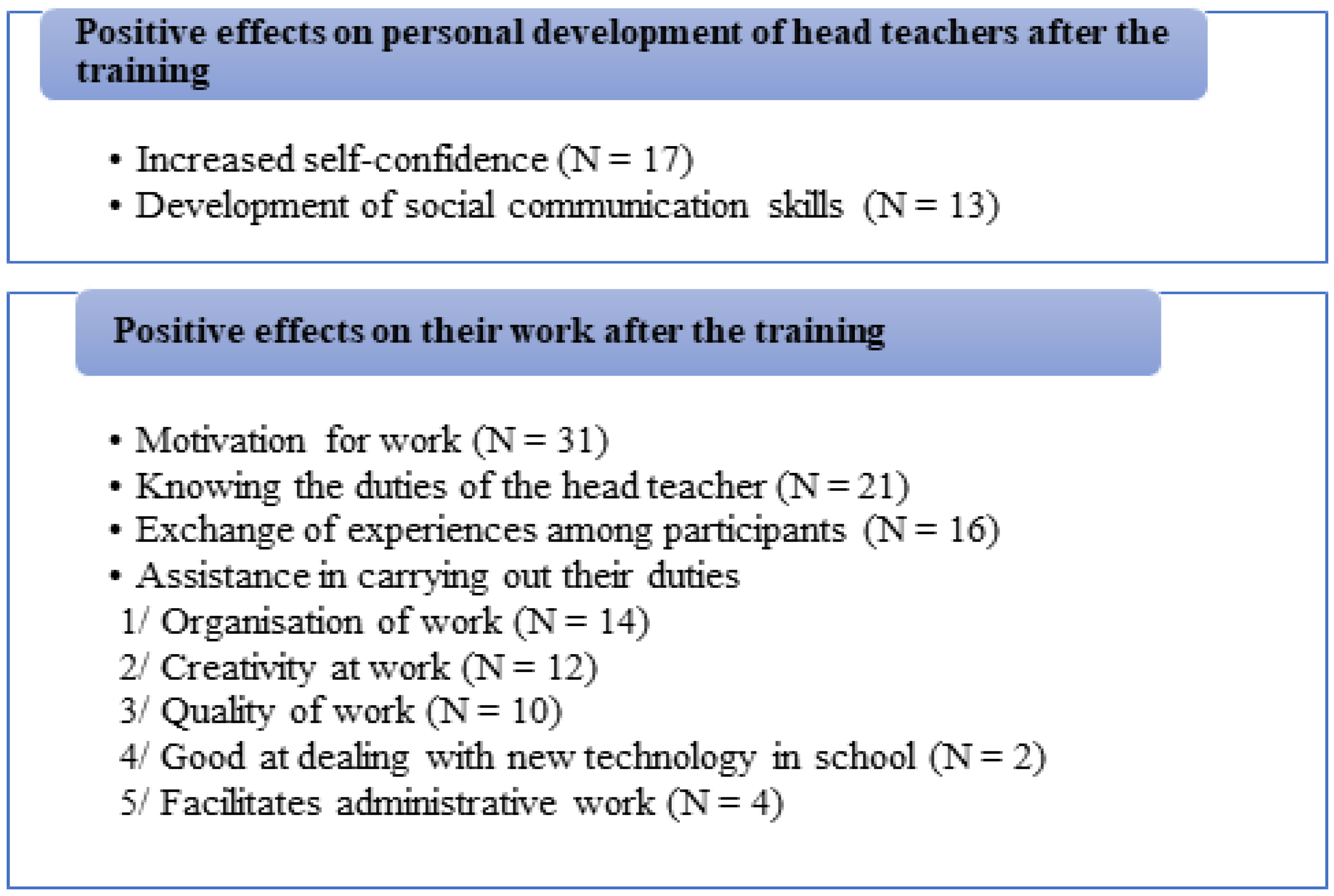

Figure 2 indicates the sample size of participants who mentioned that.

We divided these changes into two themes: (1) positive impact of the training on the personal development of head teachers and (2) positive impact on their work. The first theme included items such as increased self-confidence, with trainee #42 saying that she felt “self-confident after training” and #49 stating that her “self-confidence increased after training”. Moreover, communication skills with others, such as teachers, students and their parents, were enhanced. For example, one trainee (#75) believed that “training developed our communication skills with staff members and students in school”. Moreover, eight supervisors referred to the development of trainee head teachers’ skills in communicating with others as a result of training. Under the second theme, positive impact on work, the major positive change that the participants noticed in their behaviour after the training and reported in this study was the motivation to transfer learning to their work, with 31 trainees stating that they intended to use and apply the training content in their job. For example, one trainee (#13) stated “I felt motivation for work after the training programme”, and another (#25) asserted that “the training gave me strong motivation to work according to education systems”. They may now be confident in using the skills and aware of where demonstration of the new skills in work situations is appropriate [

124], or they believe that the new training knowledge and skills are helpful in solving work-related problems and meeting frequent job demands [

124].

Increased motivation to work is one of the most significant results indicating the success of a training programme [

125], and it is the main goal for designers of training [

126].

In addition, the trainee head teachers believed that the training programmes helped them to perform their duties and responsibilities as head teachers in several ways. First, they explained that training helped them to organise their work, which is necessary since they have many overlapping jobs and responsibilities, such as organising meetings and agendas, discussing protocols of the educational process, following up in meetings and implementing measures [

127]. Another aspect that trainees reported was that the training helped them to improve their creativity at work. Creativity is generally defined as the production of new, useful ideas or solutions to problems [

128]. Therefore, the trainees believed that the training programmes and what they included, and the exchange of experiences with peers, inspired them to be creative at work and find solutions to the problems they face.

Moreover, ten trainee head teachers believed that training helped them to perform their tasks in the correct manner, which enhanced the quality of their work, and four trainees believed that training facilitated their performance of tasks. The trainee head teachers might be new head teachers in the position and feel that leadership tasks are onerous and difficult; therefore, the training programmes help them by teaching them how to fulfil their role. Finally, two trainees believed that the training helped them to deal with new technology in education, which two supervisors cited as a positive impact of training. The ability to use new technology, including devices, software and electronic technologies, in their work is a skill head teachers should have [

129] to facilitate their job performance.

In summary, the responses suggest that most of the respondents believed that training programmes developed their behaviour by improving their skills and enhancing the character traits they need as head teachers.

Since training has a positive influence on the performance of trainees, training-related changes should result in improved job performance of trainees and other positive changes, such as acquisition of new skills, attitudes and motivation [

130]. The Ministry of Education’s efforts to train, support and induct head teachers provide a strong foundation to enable them to acquire the required leadership skills and to help them change their behaviour positively.

Conversely, 12 participants (4.8%) did not believe that the changes after training were positive. They attributed this to four barriers that affected positive behavioural changes after training: the limited professional skills of the trainer, the type of training delivery, content of training that includes repetition and lack of content diversity of training and the lack of preparedness of the training environment.

5.4. The Effect of Trainees’ Characteristics on Learning and Behavioural Change

This subsection will explore whether there is a relationship between independent variables (the age, qualifications and experience of participants) and dependent variables, namely change in the learning and behaviour of training participants, by using a stepwise linear regression test. The results on the relationship between the age and change in the learning and behaviour of participants are displayed in

Table 9.

Table 9 illustrates that there is no correlation between age and learning and behaviour change, since R

2 has very small values. In addition, the regression analysis is not statistically significant: for learning, F = 1.139 and Sig. (significance level) = 0.287 (>0.05), and for behaviour, F = 0.954 and Sig. = 0.330 (>0.05). This result indicates that the effectiveness of training programmes and self-reported change in the learning and behaviour levels of the trainees neither depends on nor is influenced by the age of the trainees.

Table 10 explores the influence of the head teachers’ experience on learning and behaviour after training programmes.

Table 10 illustrates that there is no correlation between experience and responses to learning and behaviour, since the R

2 has very small values.

In addition, regression is not statistically significant, with F = 0.481 and Sig. = 0.489 (>0.05) for learning, and F = 3.675 and Sig. = 0.056 (>0.05) for behaviour. These results show that the number of years of experience of head teachers does not influence the degree of self-reported change affected by training programmes through learning and behaviour.

Table 11 explores the correlation between head teachers’ qualifications and responses to learning and behaviour. It confirms that there is a weak positive correlation between trainees’ qualifications and self-reported change in their behaviour after training, since R = 0.170 and R2 = 0.029, which indicates that the level of qualifications explains 3 percent of the variance in behaviour.

Furthermore, the regression is statistically significant, with F = 7.379 and Sig. = 0.007 (<0.05). Therefore, the result shows that the change in the behaviour of participants after training is affected by their level of qualifications while the result for learning is not significant.

Table 12 shows the extent to which qualifications affect behaviour.

Table 12 displays the coefficients of regression models, which indicate that the behaviour of participants was affected by their qualifications, since an increase of one unit in the level of qualifications led to an increase in participants’ behaviour scores of 0.264.

Therefore, a positive relationship was found between participants’ behavioural change after training and their qualification level. The more qualified participants were, the more they were able to modify their behaviour after training as compared with those who were less qualified; that is, the trainees’ qualification level appears to affect their impact in terms of the training outcomes. Trainees with a high level of education tend to be more motivated learners and accomplish more [

131]; therefore, they are more ready to accept new studies and modern theories and transfer them to the workplace.

The literature indicates that the trainees’ personal characteristics exert an influence on or play a critical role in the level of variance in training outcomes [

132]. These characteristics include demographic variables such as age, degree held and experience [

133]. Such a difference was not found in this study in relation to age and experience; however, the results of this study agree with the literature indicating that trainees’ qualifications affect training outcomes.

This finding is significant, as it demonstrates the need for training centres and training organisers to intensify their training efforts for diploma holders (the least qualified head teachers) and to encourage these trainees to raise their level of education. Moreover, the finding highlights the need for special, targeted training courses for this group.

5.5. Results Level

The final level was explored through interviews with the 12 supervisors.

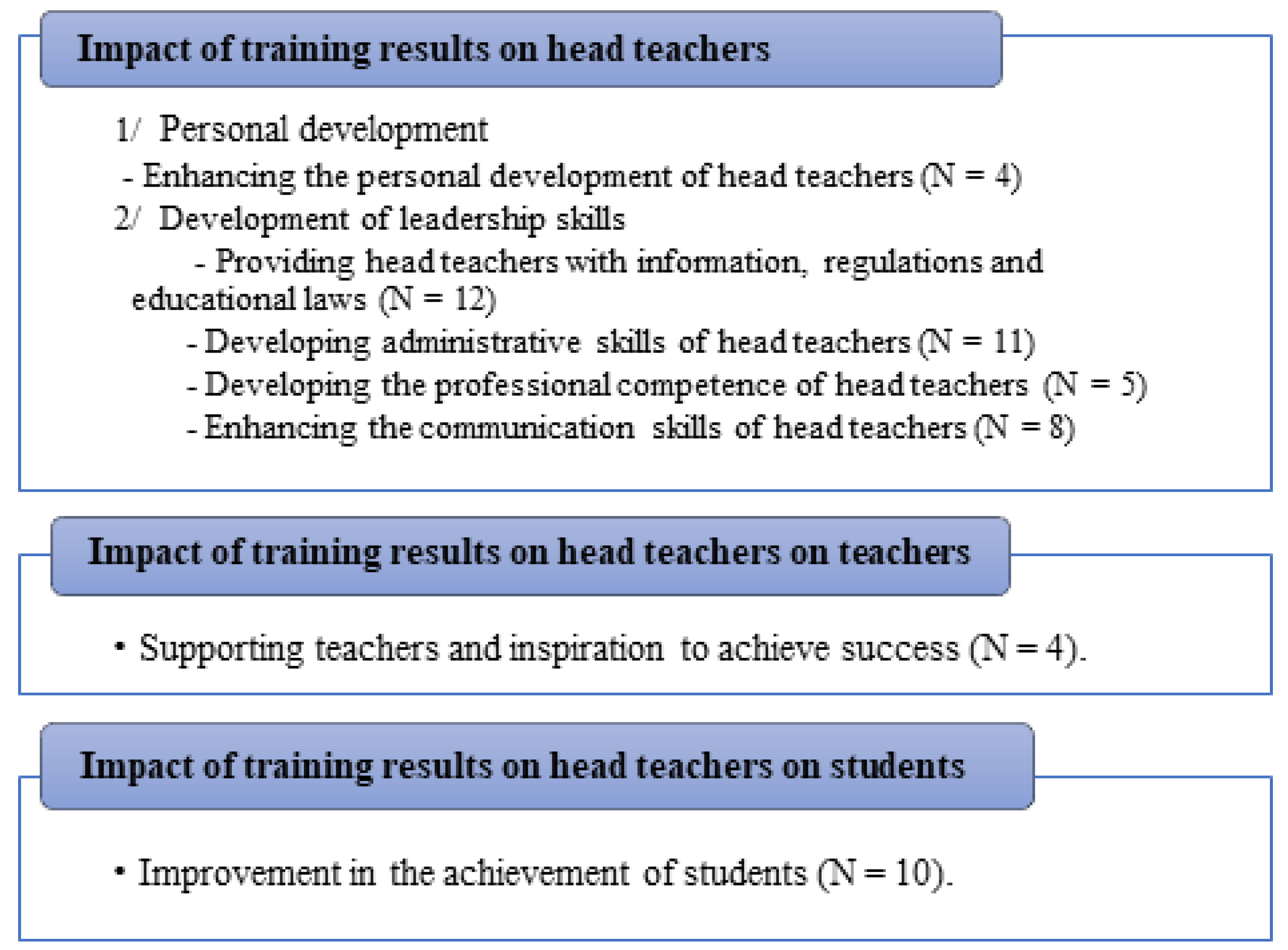

Figure 3 shows the impact of training programmes on head teachers, their work, their teachers and their students.

Supervisors’ perceptions were based on their observations and supervision of the head teachers, job performance and students’ results and achievements. In interviews, the supervisors discussed in depth the impact of the training on head teachers as the primary beneficiaries of the training process. The first aspect, their personal development in building their leadership skills, promotes building of self-confidence and enhancement of social communication skills. This confirms the beliefs of head teachers, as they reported these positive changes in their responses, as discussed in the previous section. The second aspect raised was the development of leadership by providing head teachers with information about regulations and educational laws, developing their administrative skills and enhancing their professional competence and communication skills. These supervisors believed that the training programmes had satisfactory outcomes at the level of head teachers, as supervisor #4 asserted that “training has a positive effect on the improvement and development of the administrative work of the head teachers, as there is data and information at the end of each academic year to measure the results of training on the work of head teachers, and our data indicates the qualitative and quantitative improvement in the administrative behaviour of the head teachers in the school and in the work as a whole”.

Regarding the impact of head teachers’ training on teachers, only four supervisors reported on how the training of head teachers impacted teachers who work in their schools. For example, one supervisor (#2) reported that “if the head teacher has training, this is reflected in her behaviour with her teachers. She supports them to develop their skills and removes barriers to their success in teaching”.

The impact of head teachers’ training on their teachers was noted through their enhanced support of the performance of teachers by inspiring them, which removes barriers to their success, improves their creativity and encourages them to achieve success in their job. This is consistent with the literature, which emphasises the importance and influence of a school principal on her teachers and their professional performance [

90]. Similarly, it aligns with Karaköse’s [

134] assertion that the behaviour and attitudes of leadership influence the actions, attitudes and perspectives of staff.

More attention was given to the ways that training of head teachers were reflected in the achievements of their students. Ten supervisors reported that the training reflected positively on the level of students’ results. The supervisors indicated this outcome through evidence drawn from annual evaluations of head teachers and students.

Other supervisors explained how the training programmes had improved students’ achievement; for example, supervisor #4 reported that “the results of the training and the development of the head teachers are reflected in the teachers who push students to attain high and satisfactory achievements”. In addition, supervisor #8 asserted that “for head teachers who undertake training, that is reflected in their school students. We find that their achievements and results are high because after training, the head teachers create a school climate for students to succeed and encourage students to achieve and they have more contact with parents to support students”.

In general, the analysis showed that programmes provided by the Ministry of Education to train head teachers in Saudi Arabia and prepare them for their roles provided a strong foundation, enabling them to acquire the required leadership skills. However, there were some barriers to the effectiveness of training programmes. Therefore, there is a need to identify the measures that can help to overcome these barriers and to design effective training that helps with the transfer of knowledge to the work environment.