Evaluation of Diversity Programs in Higher Education Training Contexts in Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Reality and Evolution of Disability in Universities

2. Materials and Methods

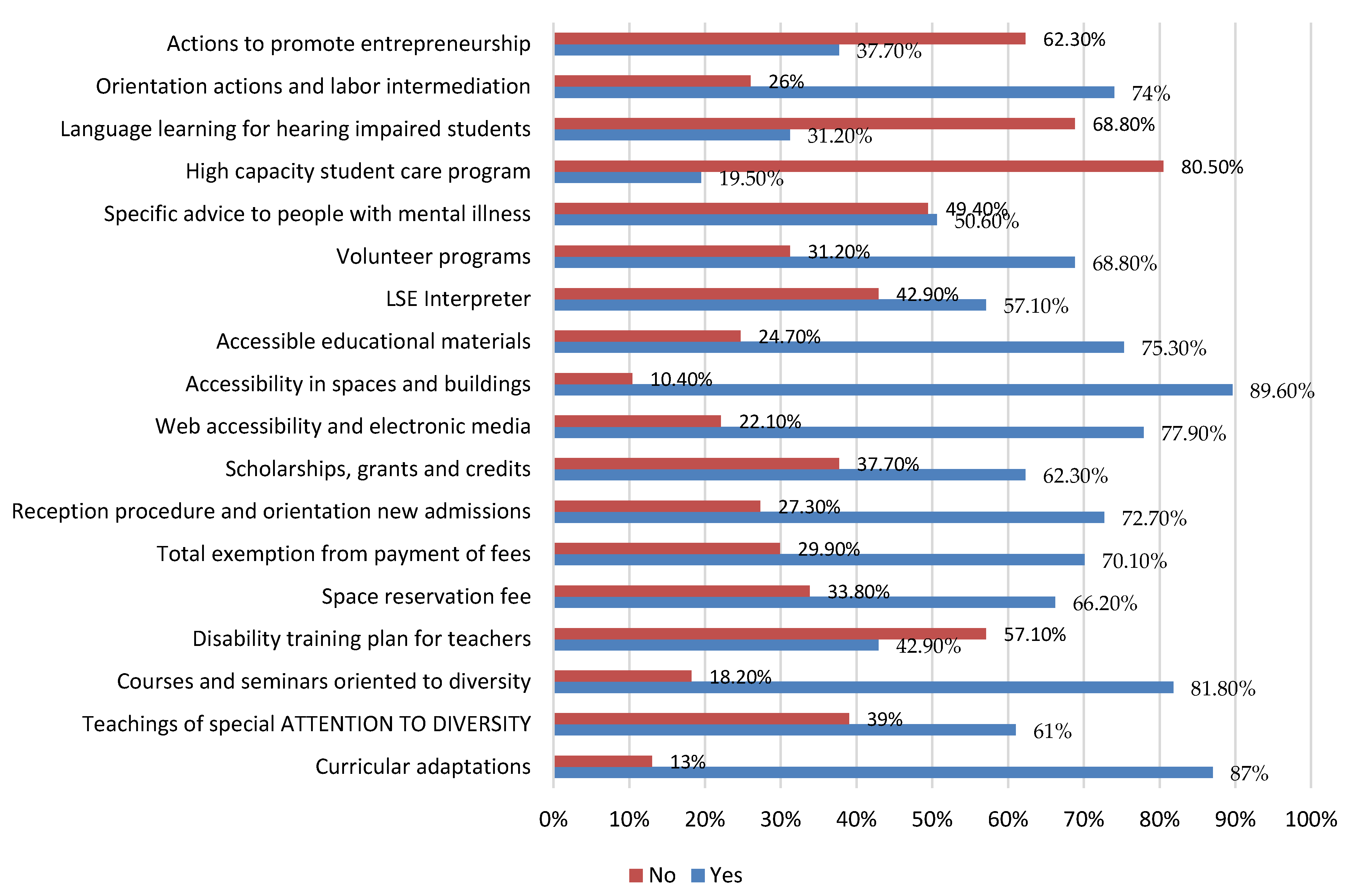

3. Results

3.1. University Type (Public/Private)

3.2. Teaching Modality (Face-to-Face/Virtual)

3.3. Autonomous Communities with More Than 10 Universities

3.4. Communities with Four and Eight Universities

3.5. Communities with three or Fewer Universities

3.6. Students with Disabilities in Universities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruiz-Ruiz, J.; Pérez-Jorge, D.; García García, L.; Lorenzetti, G. Gestión de la Convivencia; Ediciones Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2021. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Moriña, A. Inclusive education in higher education: Challenges and opportunities. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2017, 32, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Jorge, D.; de la Rosa, O.M.A.; del Carmen Rodríguez-Jiménez, M.; Márquez-Domínguez, Y. La Identificación Del Conocimiento Y Actitudes Del Profesorado Hacia Inclusión De Los Alumnos Con Necesidades Educativas Especiales. Eur. Sci. J. 2016, 12, 64–81. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Jorge, D.; Barragán, F.; Molina-Fernández, E. A Study of Educational Programmes that Promote Attitude Change and Values Education in Spain. Asian Soc. Sci. 2017, 13, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Jorge, D.; Pérez-Martín, A.; Barragán-Medero, F.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, M.C.; Hernández-Torres, A. Self-and Hetero-Perception and Discrimination in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danforth, S. Becoming the rolling quads: Disability politics at the university of California, Berkeley, in the 1960s. Hist. Edu. Q. 2018, 58, 506–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutcheon, E.J.; Wolbring, G. Voices of ‘Disabled’ Post Secondary Students: Examining Higher Education ‘disability’ Policy Using an Ableism Lens. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2012, 5, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Jorge, D.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, M.C.; Ariño-Mateo, E.; Barragán-Medero, F. The effect of Covid 19 on synchronous and asynchronous models of university tutoring. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konur, O. Teaching disabled students in higher education. Teach. High. Educ. 2016, 211, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universia Foundation. IV Estudio Sobre el Grado de Inclusión del Sistema Universitario Español Respecto de la Realidad de la Discapacidad. 2019. Available online: https://www.consaludmental.org/publicaciones/IV-estudio-universidad-discapacidad.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- OECD. Disability at Higher Education. 2003. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/school/CBR%20Spain%20Spanish%20version.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- EADSNE-European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education. Mapping the Implementation of Policy For. Inclusive Education: An. Exploration of Challenges and Opportunities for Developing Indicators; European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education: Odense, Denmark, 2011; Available online: https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/mapping-implementation-policy-inclusive-education-exploration-challenges-and (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Eurydice. The European Higher Education Area in 2012: Bologna Process. Implementation Report; Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency. 2012. Available online: https://www.ehea.info/media.ehea.info/file/2012_Bucharest/79/5/Bologna_Process_Implementation_Report_607795.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Aguilar, N.M.; Moriña, A.; Perera, V.H. Acciones del profesorado para una práctica inclusiva en la universidad. Rev. Bras. Educ. 2019, 24, 1–19. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ebersold, S. Adapting higher education to the needs of disabled students: Development, challenges and prospects in OECD. In Higher Education to 2030; OECDiLibrary: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- López-Bastias, J.L.; Moreno-Rodríguez, R.; Díaz-Vega, M. Attention to the special educational needs of university students with disabilities: The Caussen tool as part of the educational inclusion process. Cult. Educ. 2020, 32, 27–42. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, D.; Pure, T.; Rabinowitz, S.; Kaufman-Scarborough, C. Disability awareness, training, and empowerment: A new paradigm for raising disability awareness on a university campus for faculty, staff, and students. Soc. Incl. 2018, 6, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lopez-Gavira, R.; Moriña, A.; Morgado, B. Challenges to inclusive education at the university: The perspective of students and disability support service staff. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2019, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, A. Special Needs Education Country Data 2010. European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education. 2011. Available online: https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/special-needs-education-country-data-2010_SNE-Country-Data-2010.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Bedrossian, L. Understand and promote use of Universal Design for Learning in higher education. Disabil. Compliance High. Educ. 2018, 23, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesús, M.I.; Méndez, R.; Andrade, R.; Martínez, D.R. Didáctica: Docencia y método. Una visión comparada entre la universidad tradicional y la multiversidad compleja. Rev. Teor. Didact. Cien. Soc. 2007, 12, 9–29. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Morín, E. Introducción al Pensamiento Complejo; Gedisa: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1998. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Morín, E. Los Siete Saberes Necesarios Para La Educación Del Future; Santillana: Madrid, Spain, 1999. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Morín, E. La Cabeza Bien Puesta. Repensar La Reforma. Reformar El Pensamiento; Nueva Visión: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2001. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Lanz, R.; Fergusson, A. La Reforma Universitaria en el Contexto de la Mundialización del Conocimiento (Documento Rector). Available online: http://debatecultural.org/Observatorio/RigobertoLanz22.html (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- López Gavira, R.; Moriña, A. Hidden Voices in Higher Education: Inclusive Policies and Practices in Social Science and Law Classrooms. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2015, 19, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, S. Student suggestions for improving learning at university for those with learning challenges/disability. In Strategies for Supporting Inclusion and Diversity in the Academy; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2020; pp. 329–352. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.; Aquino, K.C. (Eds.) Disability as Diversity in Higher Education: Policies and Practices To Enhance Student Success; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aust, R. Disability in higher education: Explanations and legitimisation from teachers at Leipzig University. Soc. Incl. 2018, 6, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillotta, F.; Rozengarten, T.; Mahar, C. Inclusive post-secondary education: The university experience for people with an intellectual disability. In Proceedings of the 4th IASSIDD Europe Congress, Vienna, Austria, 15 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Araya-Cortés, A.; González-Arias, M.; Cerpa-Reyes, C. Actitud de universitarios hacia las personas con discapacidad. Educ. Educ. 2016, 17, 289–305. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, J.F.; Abad, M. La incorporación a los estudios superiores: Situación del alumnado con discapacidad. Rev. Qurriculum 2009, 22, 165–188. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- De la Red, N.; De La Puente, R.; Gómez, M.C.; Carro, L. El Acceso a los Estudios Superiores de las Personas con Discapacidad Física y Sensorial; Universidad de Valladolid: Valladolid, Spain, 2002. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, G.; Lledó Carreres, A. Dificultades Percibidas por los Docentes Universitarios en la Atención del Alumnado con Discapacidad; Ediciones Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Parra, D.J.L.; Luque-Rojas, M.J.; Bandera, E.E.; Arjona, D.C.; del Portal, L.M.I. Estudiantes universitarios con discapacidad. Cuestiones para una reflexión docente en un marco inclusivo. Rev. Educ. Incl. 2019, 12, 131–151. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, A.; Álvarez, E. Estudiantes con discapacidad en la Universidad. Un estudio sobre su inclusión. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2016, 25, 457–479. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alcantud, F.; Ávila, V.; Asensi, C. La Integración de Estudiantes con Discapacidad en los Estudios Superiores; Universitat de València Estudi General: València, Spain, 2000. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Méndez, R.; Martínez, D.R.; De Jesús, M.I.; Andrade, R. El aula de la educación superior: Un enfoque comparado desde la visión y misión de la universidad tradicional y la multiversidad compleja. Educere 2008, 12, 41–52. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Barragán-Medero, F.; Pérez-Jorge, D. Combating homophobia, lesbophobia, biphobia and transphobia: A liberating and subversive educational alternative for desires. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. Educación 2030. 2016. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656_spa (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Arias, M.G.B.; de Luna Velasco, L.E. Actitudes de alumnos hacia las personas con discapacidad en el centro universitario del sur. Enseñ. Investig. Psicol. 2019, 65–78. Available online: https://www.revistacneip.org/index.php/cneip/article/view/59 (accessed on 1 December 2020). (In Spanish).

- Bastías, J.L.L.; Rodríguez, R.M. Las actitudes de los estudiantes universitarios de grado hacia la discapacidad. Rev. Educ. Incl. 2019, 12, 51–65. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Moore, E.J.; Schelling, A. Postsecondary inclusion for individuals with an intellectual disability and its effects on employment. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2015, 19, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abreu, M.; Hillier, A.; Frye, A.; Goldstein, J. Student experiences utilizing disability support services in a university setting. Coll. Stud. J. 2017, 50, 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- Giust, A.M.; Valle-Riestra, D.M. Supporting mentors working with students with intellectual disabilities in higher education. J. Intellect Disabil. 2016, 21, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ONCE Foundation. Informe de la funcación ONCE. 2019. Available online: https://biblioteca.fundaciononce.es/publicaciones/colecciones-propias/memoria-de-actividades/informe-de-valor-compartido-2019-de (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Cayo, L. Guía para la elaboración de un Plan de acción al alumnado con discapacidad en la universidad. Cuest. Univ. 2008, 6, 103–116. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Observatorio Estatal de la Discapacidad. 2020. Available online: https://www.observatoriodeladiscapacidad.info/comienza-el-curso-2019-2020-situacion-de-las-personas-con-discapacidad-en-las-universidades-espanolas/ (accessed on 19 November 2020).

- Universia Foundation. Disability Care at University. 2018. Available online: https://www.fundacionuniversia.net/content/dam/fundacionuniversia/pdf/guias/Atencion-a-la-discapacidad_2018.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Observatorio Internacional de Reformas Universitarias. 2005. Available online: http://debatecultural.com/Observatorio/RigobertoLanz22 (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Bilbao, M.C.; Martínez, M.A.; De Juan, M.N.; García, M.I. Evolución de los servicios de apoyo a personas con discapacidad en las universidades españolas. In Proceedings of the I Congreso Internacional Universidad y Discapacidad, Madrid, Spain, 22–23 November 2012. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, D.; Schreuer, N. Inclusion of Students with Disabilities in Higher Education: Performance and Participation In Student’s Experiences. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2012, 31, 1561–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, P.R.; Alegre, O.M.; López, D. Las dificultades de adaptación a la enseñanza universitaria de los estudiantes con discapacidad: Un análisis desde un enfoque de orientación inclusiva. Relieve 2012, 18, 1–18. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conder, J.; Mirfin-Veitch, B.; Payne, D.; Channon, A.; Richardson, G. Increasing the participation of women with intellectual disabilities in women’s health screening: A role for disability support services. Res. Pract. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 6, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, E.; Verdugo, M.A.; Campo, M.; Sancho, I.; Alonso, A.; Moral, E.; Calvo, I. Protocolo de Actuación Para Favorecer la Equiparación de Oportunidades de los Estudiantes con Discapacidad en la Universidad; Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 2008. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Forteza, D.; Ortego, J.L. Los servicios y programas de apoyo universitario para personas con discapacidad. Estándares de calidad, acción y evaluación. Rev. Educ. Espec. 2003, 33, 9–26. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Lipka, O.; Forkosh Baruch, A.; Meer, Y. Academic support model for post-secondary school students with learning disabilities: Student and instructor perceptions. Int.J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, E.; Cayo, L. Guía de Recursos Sobre Universidad y Discapacidad; Grupo Editorial Cinca: Madrid, Spain, 2006. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Avramidis, E.; Norwich, B. Teachers’ attitudes toward integration/inclusion: A review of the literature. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2002, 17, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, K. Educación inclusiva: Concepciones del profesorado ante el alumnado con necesidades educativas especiales asociadas a discapacidad. Rev. Educ. Incl. 2019, 12, 171–186. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, J.M. Competencias docentes para la inclusión del alumnado universitario en el marco del Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior. Rev. Educ. Incl. 2011, 4, 137–147. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Pais, M.E.M.; Salgado, F.R. La atención a la diversidad en el aula: Dificultades y necesidades del profesorado de educación secundaria y universidad. Contextos Educ. Rev. Educ. 2020, 25, 257–274. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, M.D.; Álvarez, Q.; Malvar, M.L. Accesibilidad e inclusión en el Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior: El caso de la Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. Aula Abierta 2012, 40, 71–82. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Guasch, D.; Dotras, P.; Llinares, M. Los Principios de Accesibilidad Universal y Diseño; para Todos en la Docencia Universitaria; Universidad de Córdoba: Córdoba, Spain, 2010. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Broomhead, K.E. Acceptance or rejection? The social experiences of children with special educational needs and disabilities within a mainstream primary school. Education 3–13 2019, 47, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnasser, Y.A. The perspectives of Colorado general and special education teachers on the barriers to co-teaching in the inclusive elementary school classroom. Education 3–13 2020, 48, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Brown, Z.; Hodkinson, A. What is considered good for everyone may not be good for children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities: Teacher’s perspectives on inclusion in England. Education 3–13 2020, 48, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Regulatory Development | Inputs |

|---|---|

| Organic Law 6/2001, Organic Law of Universities (LOU) | Promulgates equal opportunities and non-discrimination, configuring them as student rights. Universities are responsible for their statutory development. Introduction and promotion of active policies that guarantee the accessibility of the university environment, as well as equal opportunities for people with disabilities who are at the university. |

| Organic Law 4/2007, which modifies Organic Law 6/2001. | Organizational and structural changes focused on the design of degrees and on the roles of teachers and students. |

| Royal Decree 1791/2010. | It approves the Statute of the University Student and supposes a modification of the LOU. It contains 17 articles in relation to the group of students with disabilities: basic principles of non-discrimination (arts. 4 and 13.j), participation (arts. 38.3.c, 38.5, 62.5 and 64.4), representation (arts. 35.5 and 36. f), access and admission (art. 15), tutorials (art. 22), academic practices (art. 24.4); mobility (art. 18), assessment tests (art. 26), communication and review of grades (arts. 29.2 and 30.2) and creation of student care services (arts. 65.5 to 8 and 66.4). Article 12.b obliges universities to establish the necessary resources and adaptations so that students with disabilities exercise all their rights on equal terms without lowering their academic level. |

| Law 26/2011. | Normative adaptation to the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Designation of the Spanish Committee of Representatives of People with Disabilities (CERMI) as a supervisory and control body, which controls universities in the application of the Convention and regulations on disability. |

| Royal Legislative Decree 1/2013 of November 29, which approves the Consolidated Text of the General Law on the rights of people with disabilities and their social inclusion Royal Legislative Decree 1/2013 of November 29, by which approves the Consolidated Text of the General Law on the rights of persons with disabilities. | It reiterates its commitment to the principles and mandates of the convention and international and national regulations. They establish the following mandates: (a) education must be inclusive, of high quality and free; (b) equality of conditions must be respected; (c) guarantees to be ensured by educational administrations; regulation of support and reasonable adjustments, especially in learning, and inclusion of students who require special attention. |

| Royal Decree 412/2014, which establishes the regulations for the admission procedures for official undergraduate university studies | It establishes access to undergraduate education from the principles of equality and non-discrimination, and the accessibility of entrance exams for students with disabilities or special needs. Regarding the entrance tests, it establishes the appropriate measures with respect to the organizing committees of the tests and the qualifying processes. Place reservation system for disabled people; 5% for students who have a recognized disability level of at least 33%. |

| Royal Decree 592/2014. | Regulates the external academic practices of university students and establishes: That they are accessible to students with disabilities, ensuring the availability of the necessary human, material and technological resources that ensure equal opportunities. Have the necessary resources for the access of students with disabilities to guardianship, information, evaluation and the performance of the practices in equal conditions. Reconcile for students with disabilities, practical lessons with activities and personal situations derived from the disability situation. |

| 2011–2012 | 2013–2014 | 2015–2016 | 2017–2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undergraduate | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.8% | 1.8% |

| Postgraduate and Master | 0.5% | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.2% |

| Doctorate | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.9% | 0.7% |

| Gender | Studies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Undergraduate | Postgraduate | Doctorate | |

| Women | 49.1% | 48.7% | 43.4% |

| Men | 50.9% | 51.3% | 56.6% |

| Type of disability | |||

| Physical | 55.9% | ||

| Psychosocial/Intellectual/Developmental | 26.5% | ||

| Sensory | 17.6% | ||

| Branch of studies | |||

| Social and Legal Sciences | 54% | ||

| Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics | 26% | ||

| Arts and Humanities | 19.5% | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Jorge, D.; Ariño-Mateo, E.; González-Contreras, A.I.; del Carmen Rodríguez-Jiménez, M. Evaluation of Diversity Programs in Higher Education Training Contexts in Spain. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050226

Pérez-Jorge D, Ariño-Mateo E, González-Contreras AI, del Carmen Rodríguez-Jiménez M. Evaluation of Diversity Programs in Higher Education Training Contexts in Spain. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(5):226. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050226

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Jorge, David, Eva Ariño-Mateo, Ana Isabel González-Contreras, and María del Carmen Rodríguez-Jiménez. 2021. "Evaluation of Diversity Programs in Higher Education Training Contexts in Spain" Education Sciences 11, no. 5: 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050226

APA StylePérez-Jorge, D., Ariño-Mateo, E., González-Contreras, A. I., & del Carmen Rodríguez-Jiménez, M. (2021). Evaluation of Diversity Programs in Higher Education Training Contexts in Spain. Education Sciences, 11(5), 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050226