Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused a worldwide unexpected interruption of face-to-face teaching and a sudden conversion to emergency remote teaching (ERT). In this exploratory study, a sample of 244 secondary mathematics teachers was considered to analyze their perception of their readiness to ERT during the COVID-19 pandemic based on their technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK), their previous training in digital teaching tools, their level of digital competence for teaching mathematics, and their adaptation to ERT. An online questionnaire was applied, and the answers were quantitatively analyzed. Given the use of a large number of digital resources and the high percentage of self-developed materials using educational software, secondary mathematics teachers reflected adequate digital competence and TPCK for teaching mathematics. The sudden transition to ERT forced teachers to slow down the pace of teaching and to reduce the content taught. Significant differences were observed based on gender and age with respect to teachers’ perception of their adaptation to ERT. Despite the positive influence of previous training on their perception of readiness for ERT, in general, teachers recognized that they need more training. The demand for preparation for video editing and online quiz composition can be considered for the design of future training programs.

1. Introduction

Despite the importance that information and communications technology (ICT) acquired in the teaching and learning of mathematics in the last quarter of the 20th century, the challenges for teachers in the 21st century are exponentially increasing. Today, teachers must face a generation of students who were born in a digital world, being users of different devices and having access to the Internet since their early childhood [1].

Teachers are now being asked not only to transmit knowledge, but to promote the integral development of their students, including digital literacy. There are different definitions of this term, some of which relate it with other literacies, such as reading literacy, mathematical literacy, media literacy, or data literacy [2]. The Horizon Report [3] highlights three dimensions of digital literacy: universal literacy (using basic digital tools, mainly referring to software and the Internet), creative literacy (more advanced skills in producing richer content such as videos, animations, or programming) and literacy across disciplines (specific applications to a certain knowledge domain and learning context).

Research has focused on how teachers are trained in different ICT tools, how ICT is integrated into the curriculum or into the classroom, the impact of ICT on teaching and learning, or teachers’ attitudes towards the use of ICT [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Additionally, the teaching and learning of mathematics in a digital context has attracted the attention of researchers to the efficiency of different modalities, resources, or platforms, the attitudes and behavior of students, the social and contextual variables, or the didactic features of specific domains [10,11,12,13,14]. However, before the COVID-19 pandemic, few research studies had been developed about how mathematics teachers’ technological knowledge, previous training in digital teaching tools, and digital competence level influence their readiness to teach within remote teaching environments [9].

1.1. Teaching during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, almost all countries had to temporarily interrupt face-to-face teaching to keep teachers, students, and staff members safe. In Spain, the context in which this research was developed, face-to-face teaching was interrupted at all educational levels (university included) from 10 March 2020 to the end of the academic year (July 2020). To sustain instruction during the pandemic, teaching and learning were forced to move to an online environment. This temporary change in the mode of instruction to using electronic devices and being completely remote due to crisis circumstances is conceptualized as emergency remote teaching (ERT) [15,16,17]. Some researchers differentiate ERT from other online teaching and learning systems (such as the different varieties of e-learning: distance learning, blended learning, or mobile learning) by arguing that the latter require careful instructional design and planning [15,16]. The closure of schools caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, in Spain and other countries, resulted in an abrupt, sudden, and unexpected rearrangement of teaching without previously planned artifacts or resources. Although e-learning was the goal teachers and schools wanted to achieve, we relied on recent literature to assume that ERT was the teaching approach implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although several research studies about this transition have been recently published [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26], few looked at the preparation of secondary mathematics teachers for ERT during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although this crisis will hopefully be a piece of history in the future, the skills of teachers to overcome this type of situation should be part of their training and professional development to guarantee the continuity of quality teaching [15,17,25].

Undoubtedly, ERT requires teachers’ readiness in terms of their technological knowledge, their training in digital teaching tools, and their digital competence for teaching, but it also needs online infrastructures and resources. Although powerful online environments have been developed in recent years, many schools were still not properly digitized when the COVID-19 pandemic struck. Furthermore, when we consider the situation in the teachers’ home, where ERT usually took place, the situation was far from optimal. A report prepared by a union during the COVID-19 pandemic [27] evidenced that 2% of teachers did not have a computer or Internet connection at home, while 12.4% of them had a poor Internet connection. According to [18], ICT facilities are a significant mediator in the relation between teachers’ readiness and ICT application in mathematics teaching and learning.

Teachers who were adequately trained in educational uses of ICT in and outside the classroom were at an optimal starting point to turn to ERT when the COVID-19 pandemic struck. However, [28] affirms that, in general, teachers receive a low level of preparation for the educational uses of ICT both in pre-service and in-service training, leaving a large part of the effort to individuals and not to institutions. Under these circumstances, ERT emphasized individual differences in teachers’ training and attitudes towards the use of ICT, which influence the quality and efficiency of teaching [28].

In Spain, there is no digital professional framework for teachers [29], but rather a ministerial body (the National Institute of Educational Technologies and Teacher Training, INTEF in Spanish acronym) established a framework of digital teaching competences [30] based on the DigCompEdu (Digital Competence of Educators) project [31]. This framework comprises five areas (information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, security, and problem solving) and three proficiency levels (A = Basic, B = Intermediate, and C = Advanced), each fine-tuned in two sub-levels. According to this framework, Spanish secondary teachers show low levels of attainment, especially in areas related to security and the creation of digital content, while they perform better in communication and information skills [13,14]. For the development of the research instrument, both the INTEF framework and previous research studies on teachers’ preparation for remote teaching were considered. In particular, the teachers’ perception of their level of digital teaching competence was measured considering the six sub-levels of competence of the INTEF framework [30].

1.2. A Model for Teachers’ Technological Pedagogical and Mathematical Knowledge

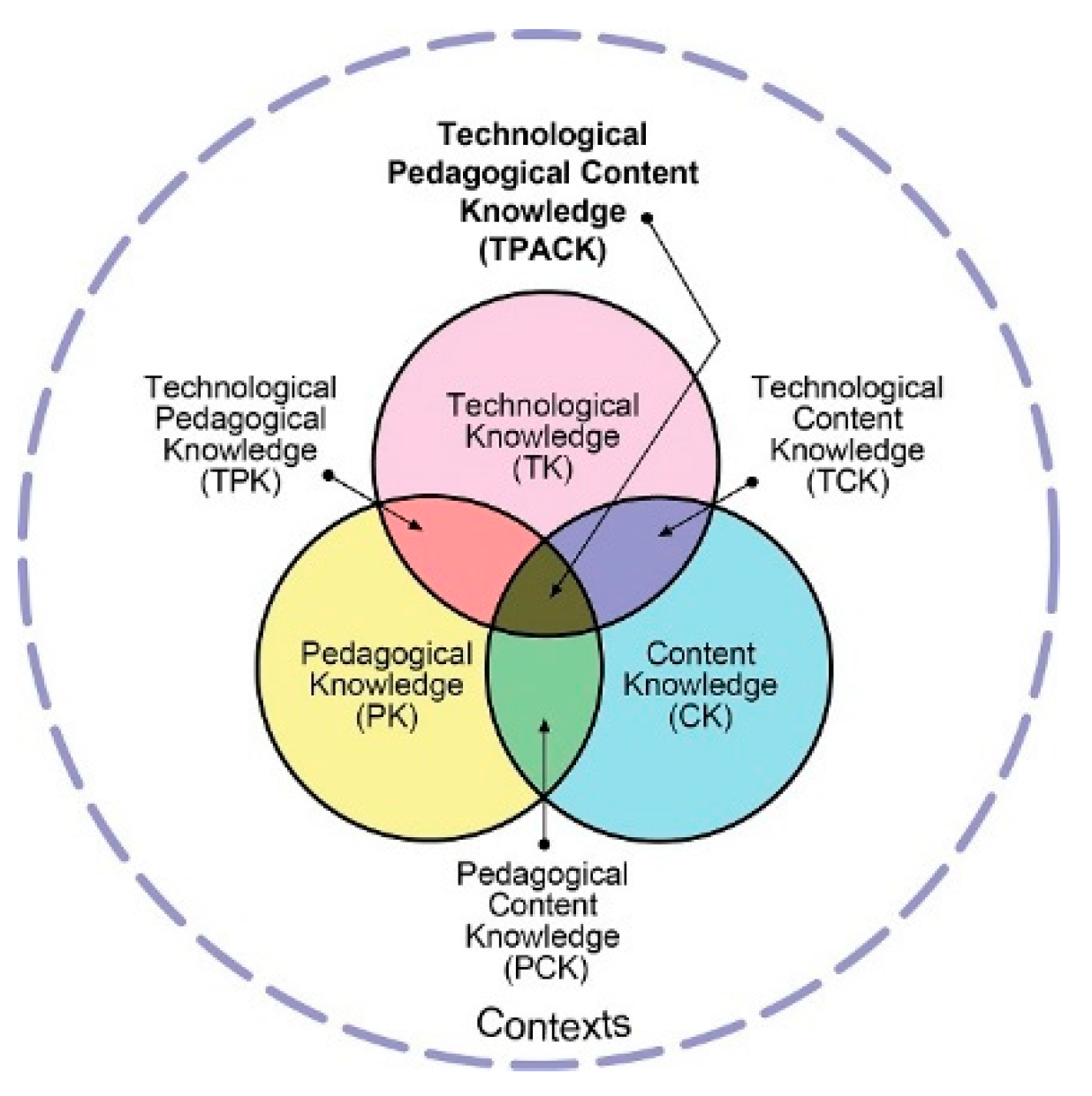

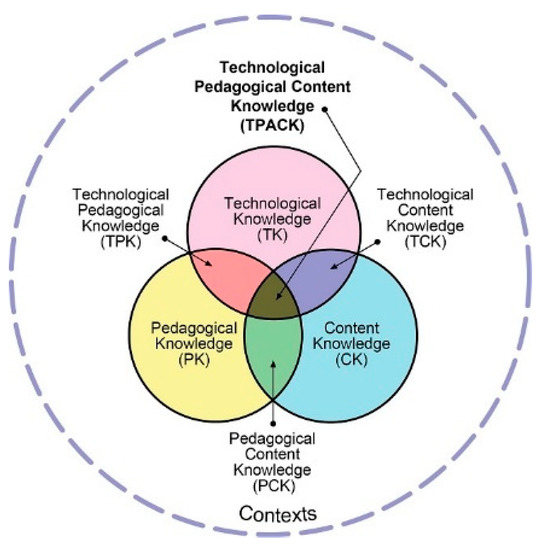

Research on the characterization of mathematics teachers’ knowledge includes a wide variety of theoretical models that conceptualize the knowledge that teachers should master for effective teaching (see [32] for a review). Some of these frameworks are aware of the introduction of technology to the educational process. In this regard Mishra and Koehler [33,34] developed the so called Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK or TPACK) framework, building on Shulman’s [35,36] notion of Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK). The PCK avoids the dichotomy between the content and the pedagogy of teaching by introducing a third domain that considers the relation between teachers’ subject-matter knowledge and pedagogical knowledge. The TPCK is consistent with the previous idea but integrates the significant role of technology in education and, therefore, in teachers’ knowledge. Thus, the approach of Mishra and Koehler’s [33,34] is based on the intersection of three sources of knowledge: content (C), pedagogy (P), and technology (T). In doing so, seven domains of knowledge emerge (see Figure 1). This framework grounds how teachers should be trained and what competences they should master in terms of readiness for the profession in a digital world.

Figure 1.

The TPACK model [37] (reproduced with permission from Tpack.org, Copyright 2012).

The authors of the model [33,34] describe each domain as follows:

- Content knowledge (CK) applies to the knowledge of concepts, theories, ideas, organizational frameworks, evidence, and proof, as well as practices and approaches necessary to develop the subject-matter knowledge to be taught. The subject-matter knowledge refers to the knowledge of the discipline. In this research study, CK concerns teachers’ mathematical knowledge.

- Pedagogical knowledge (PK) refers to the knowledge of cognitive, social, and developmental theories of learning and how they apply to students. As such, it includes an understanding of teaching and learning methods, classroom management practices, lesson planning systems, and assessment techniques.

- Technological knowledge (TK) goes beyond a basic understanding of ICT. TK requires being able to apply the appropriate digital tools to complete a specific task or to achieve a particular goal and to devise alternative ways of doing it. This domain of knowledge requires teachers to evolve as technology develops.

- Pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) alludes, in accordance with Shulman [34,35], to the transformation of the subject-matter for teaching. In mathematics, the key to PCK is not only being aware of students’ mathematical errors and misconceptions, but also making connections between the different areas of mathematics and between mathematics and other areas of knowledge and students’ contexts.

- Technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK) is particularly aligned with the universal and creative dimensions of digital literacy [3], which not only implies using digital tools for teaching, but also being able to produce educational content using ICT and understanding the contribution of ICT to a specific learning context. In this sense, TPK requires looking beyond the common uses of ICT, seeking tailored pedagogical purposes.

- Technological content knowledge (TCK) means understanding which ICT are best suited to address the specific subject-matter learning, and vice versa. In mathematics, certain technologies can assist in the representation of mathematical concepts or ideas that are tough to figure out without pictorial support. Likewise, certain mathematical notions or theories restrict the range of digital tools that are suitable for understanding such contents.

- Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK) requires an understanding of the representation of subject-matter concepts that use ICT, pedagogical techniques that use ICT to constructively teach disciplinary contents, knowledge of what makes specific subject-matter concepts are difficult or easy to learn and how ICT can help to address these problems, knowledge of students’ prior subject-matter knowledge and theories of epistemology, and knowledge of how technologies build on existing subject-matter knowledge to develop new learning or strengthen the old one. In summary, the TPCK adds the dimension of literacy across disciplines of digital literacy [3] to the TPK. In this research study, TPCK refers to the specific applications of technology for the teaching and learning of mathematics. As well as TK and TPK, this knowledge domain requires teachers to keep up to date with technology advances.

Considering the focus of this research study on secondary mathematics teachers’ perception of their readiness to ERT, it seems reasonable to build on a model with a strong emphasis on technology. Given that teaching practices inform about teachers’ TPCK [4], by knowing the practices connected to technology that teachers developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, we can obtain information about their TPCK. Obviously, this is not a complete overview of all the features in that domain, but we can infer some ideas about teachers’ readiness.

1.3. Objectives and Research Questions

The main objective of this exploratory study was to analyze the secondary mathematics teachers’ perception of their readiness to ERT under the COVID-19 pandemic based on their TPCK, their previous training in digital teaching tools, their perception of their level of digital teaching competence, and their perception of their adaptation to the ERT situation regarding different factors. The following research questions guided the achievement of this goal:

- RQ1.

- How can the TPCK of secondary mathematics teachers be described considering their teaching practices adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- RQ2.

- To what extent had secondary mathematics teachers been trained in digital teaching tools when the COVID-19 pandemic struck?

- RQ3.

- What is the secondary mathematics teachers’ perception of their level of digital teaching competence?

- RQ4.

- What factors influence secondary mathematics teachers’ perception of their adaptation to the ERT situation?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population and Sample

The target population consisted of in-service Spanish secondary mathematics teachers. A non-random sampling was carried out. The target individuals were asked to participate in the research study by means of different forms of communication, in particular e-mail and social networks. Since the invitation was linked to the authors’ Twitter® (San Francisco, CA, USA) profile (which is public), it was not possible to quantify how many people were invited to participate. The call for participation began on 25 April 2020 and ended on 4 May 2020. The start date was selected because on 25 April, Spain began the sixth week of lockdown. Thus, teachers had already had time to adapt and react to the ERT situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and they could talk about the experience with some hindsight.

The number of answers received was 250. Six of them were rejected because they were either incomplete or presented clear patterns of automatic response. Therefore, the final sample size was 244. Due to the non-randomness of the sampling, we cannot consider this sample to be representative. However, it is a fairly large sample, and few research studies about secondary mathematics teachers’ readiness to ERT can be found in the literature handling such a sample size.

Table 1 shows the age distribution of the sample. There were 151 women, 89 men, and 4 people who preferred not to be classified by gender. Regarding teaching experience, 75.4% of the sample had more than 10 years of experience, 5.3% had between 6 and 10 years, 9.8% between 3 and 6 years, and 9.4% less than three. Most of the participants (43.5%) were teaching at the two levels of Spanish secondary education (compulsory and non-compulsory), called Educación Secundaria Obligatoria (ESO) and Bachillerato in Spanish, while 36.9% of them only were teaching at ESO level and 6.6% only at Bachillerato level.

Table 1.

Age distribution of the sample.

Regarding the geographical distribution of the sample, Spain has 17 autonomous communities and 2 autonomous cities, with 16 of the regions and 1 of the cities represented in the sample. Most of the answers came from Asturias (XXX, 20.1%), Andalusia (the most populated Spanish region, 19.7%), Castile and Leon (12.3%), and Madrid (10.2%). These four regions covered two-thirds of the answers. The remaining regions were represented with a range of 0.4% to 5.3% of the answers.

2.2. Research Instrument

The research instrument consisted of a 28-item questionnaire designed and administered in Spanish using Google Forms® (Mountain View, CA, USA). A text version translated into English can be found in Appendix A. Since no previous questionnaire was useful or adaptable for the sudden situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic at the time of the data collection process, the questionnaire was designed entirely for the purpose of this exploratory study.

Construct validity was achieved by orienting the different items to what the research literature stated about the problem. Thus, in addition to certain contextual information, for designing the instrument previous research studies on ERT, teachers’ digital competence and knowledge frameworks (already addressed in the introduction) were taken into account. To address the first research question, secondary mathematics teachers’ TPCK was explored considering the teaching practices adopted by the participants during the COVID-19 pandemic (items 6–8, 15–28). To answer the second research question, the previous training of secondary mathematics teachers in digital tools was analyzed in terms of the number of training hours both in specific software for the teaching mathematics and in ICT tools and their perception of training needs (items 9–12). In view of the third research question, secondary mathematics teachers’ perception of their digital teaching competence level according to the INTEF framework and its adequacy to adapt to the ERT situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic was considered (items 13–14). Regarding the fourth research question, secondary mathematics teachers’ perception of their adaptation to the ERT situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic was measured according to different factors such as the age of the participants, their gender, their teaching experience, the educational level at which they teach (items 1–5), their previous training in digital tools, and their perception of their level of digital teaching competence.

The authors carried out the content validation after discussions with some secondary mathematics teachers and other mathematics education experts. Considering the mother tongue of the participants, the instrument was originally written and administered in Spanish (being translated into English for publication). Therefore, translation validation was not necessary. During the questionnaire administration process, no further controversial questions or content issues arose.

2.3. Data Analysis Process

Data analysis was performed using SPSS® (version 24, Chicago, IL, USA). To answer the first three research questions, all responses were first examined through descriptive statistical analysis. To analyze the factors influencing the secondary mathematics teachers’ perception of their adaptation to the ERT situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., the fourth research question), several inferential statistical analyses were carried out. In particular, we set out to determine whether there were significant differences in their teaching practices during the COVID-19 pandemic depending on age, gender, teaching experience, educational level at which they teach, previous training, and perceptions of their level of digital teaching competence. Since no normality was found in any of the distributions (according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests), Chi-square (CS), Spearman rank (SR), Mann–Whitney U-test (MW), and Kruskal–Wallis (KW) tests were used based on the different combinations and type of variables. In the next section, the acronyms CS, SR, MW, and KW, respectively, are used to refer to the tests.

3. Results

The results are organized into subsections following the four research questions.

3.1. Secondary Mathematics Teachers’ TPCK Considering Their Teaching Practices during the COVID-19 Pandemic (RQ1)

Table 2 shows the results to the question: “What platforms are you using to share educational resources, teach, and/or communicate with your students?”. When individually analyzing the answers, we found that the median number of platforms used by teachers was 3, and about 80% of the participants used two, three, or four platforms at the same time.

Table 2.

Type of platforms used with students.

For 40% of the participants, it was the first time they used any of these platforms. Likewise, 57.8% had agreed that the platform to be used with other people in the school (46.7% at school level, 9.4% at teachers’ level, and 1.6% at department level), and the rest (42.2%) acted individually.

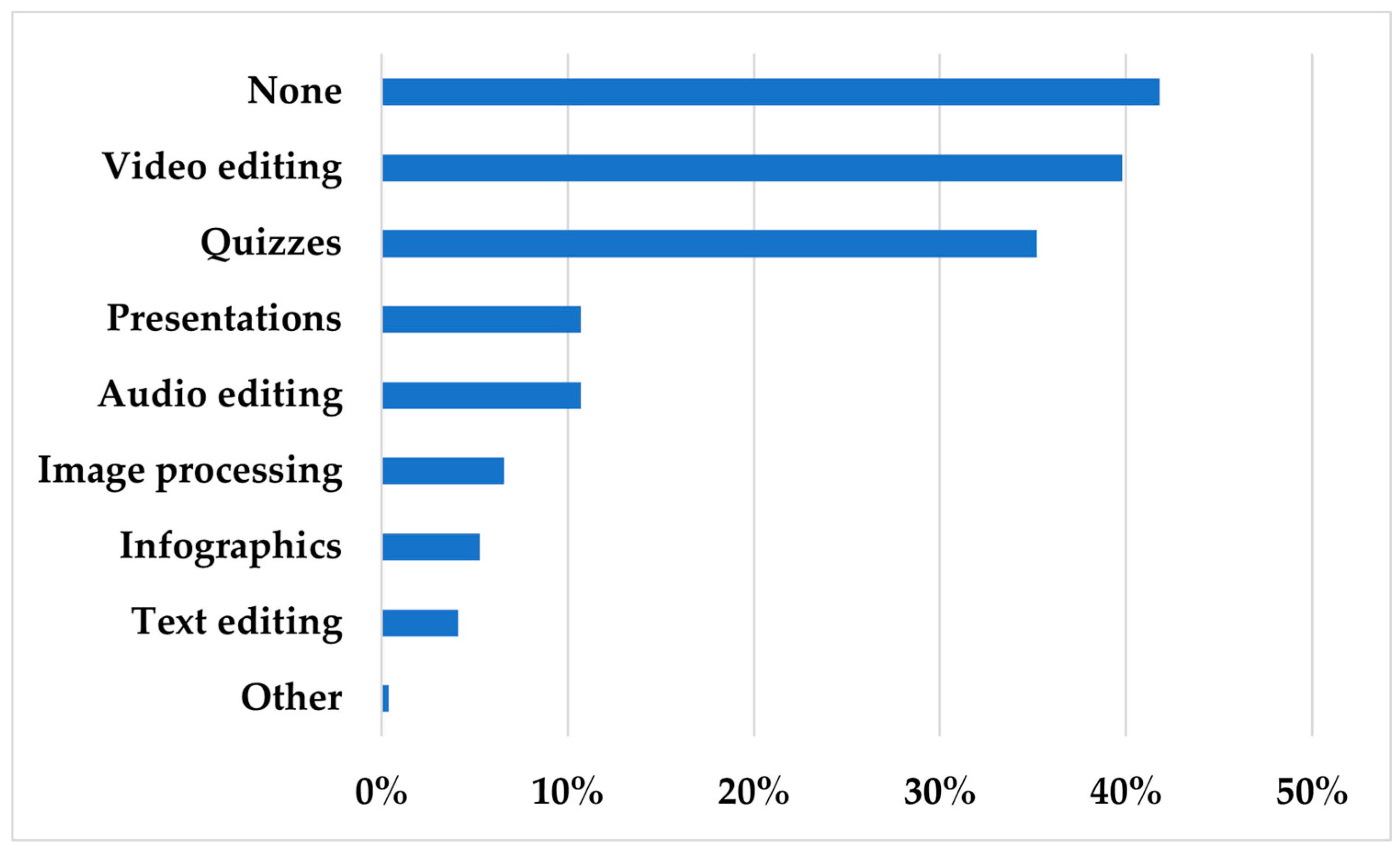

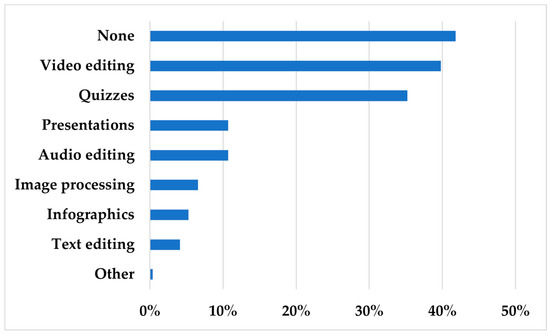

Figure 2 shows the answers to what type of editing and/or processing software teachers needed to learn due to the ERT situation. In general, 41.8% of the teachers answered that during this period they did not need to learn to use editing and/or processing programs, and only 13.93% needed to learn more than three different programs. As we can see, most of the needs focused on video editing and quiz composing. In addition, one in five participants (19.3%) recognized the need to learn specific software for teaching mathematics.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the answers about the type of editing/processing software learned.

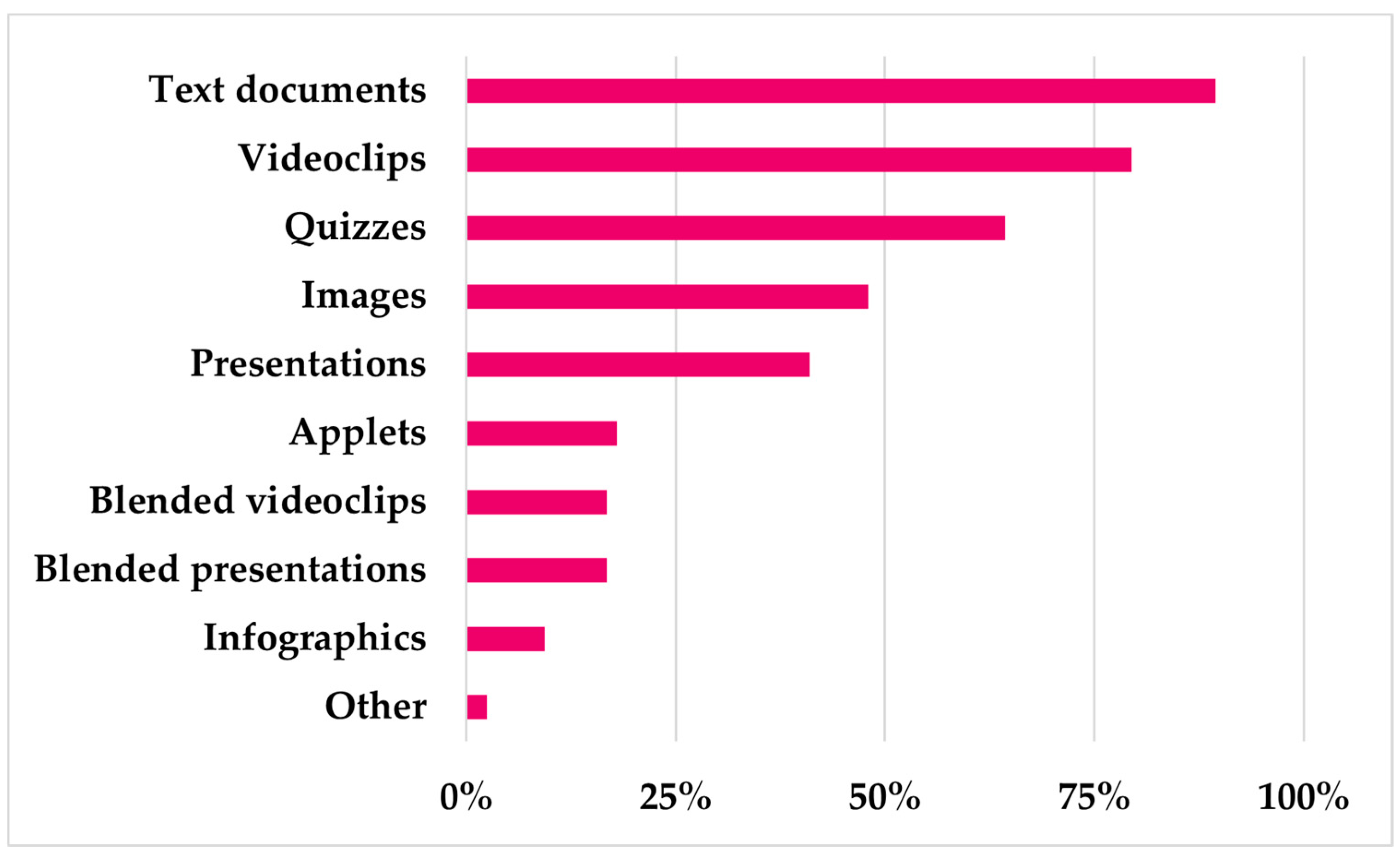

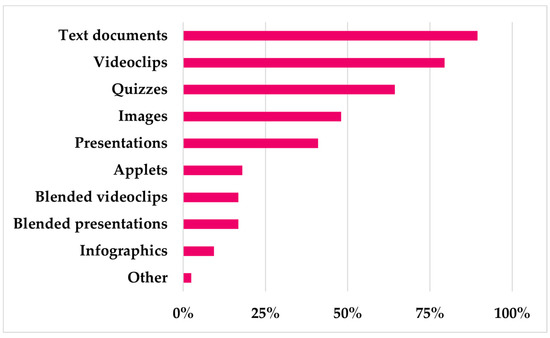

Figure 3 shows the type of resources used by teachers during the ERT period and their frequency of appearance in the sample. The median and mode number of different types of resources used was four, which shows a significant variety (for instance, 14.8% of the respondents used six different types, and 9.8% used seven types).

Figure 3.

Distribution of the answers about the type of resources used.

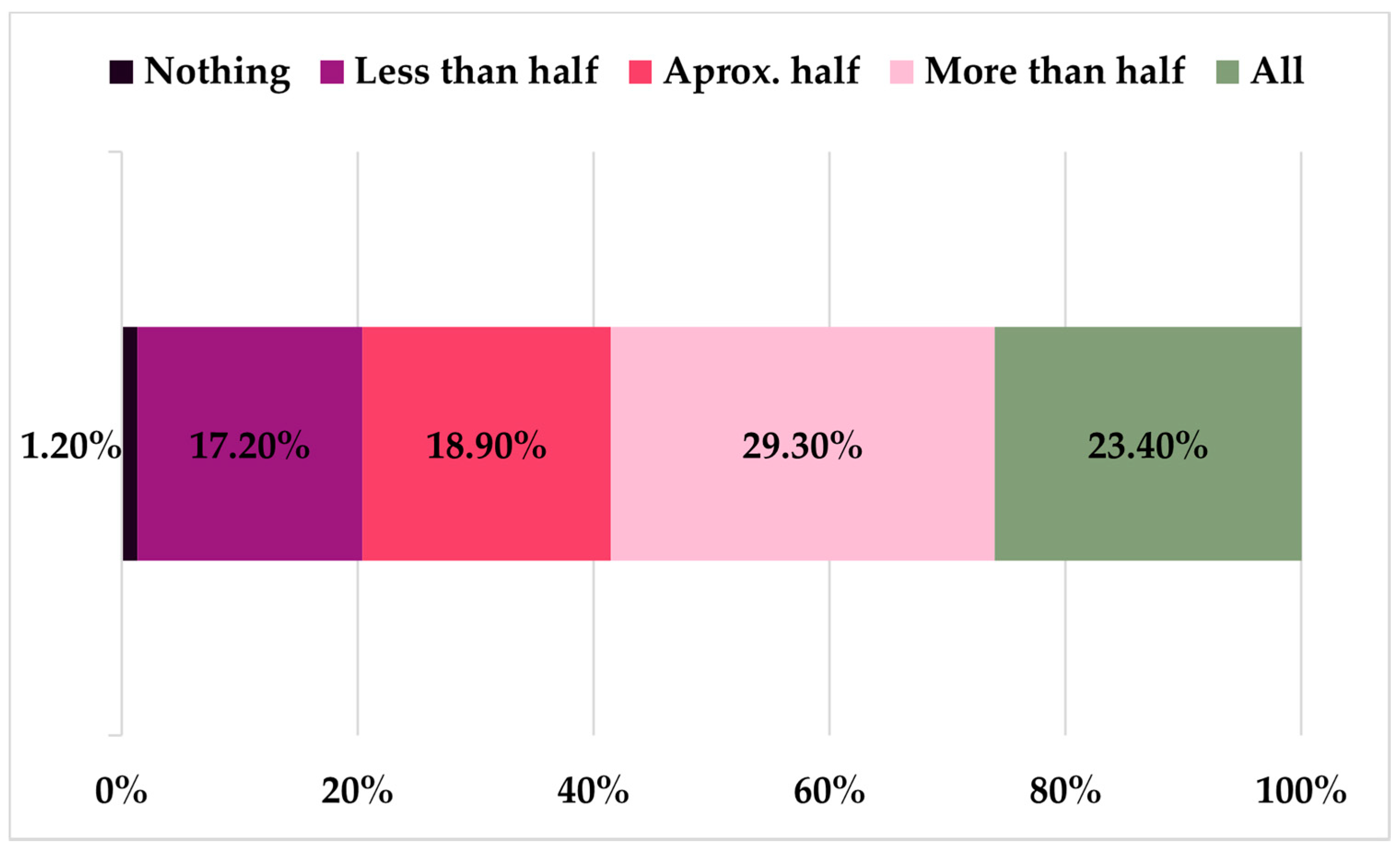

The percentage of self-developed materials was very high, since more than 50% of the participants indicated that all or more than half of the materials were developed by themselves (Figure 4). Furthermore, 69.7% of the participants acknowledged that, prior to the ERT situation, they did not have any ready-to-use or collected material usable in a remote teaching environment or simply an insufficient quantity. In this sense, 60.2% of the respondents used specific software for mathematics to make their own materials.

Figure 4.

Percentage of own-developed materials used by teachers.

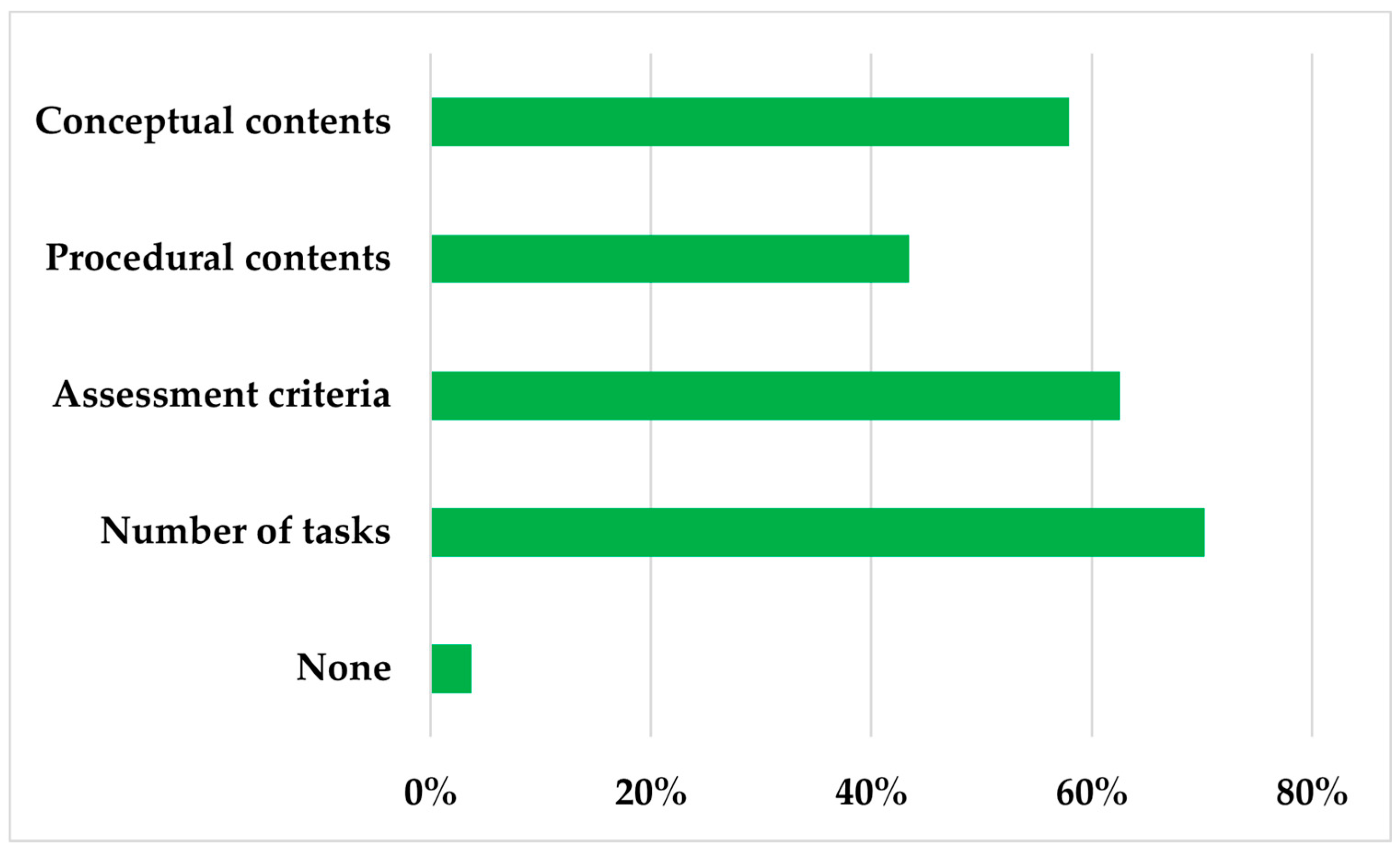

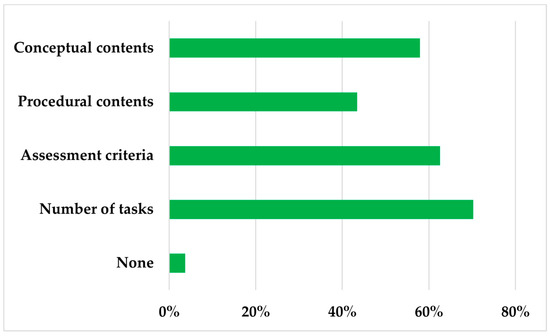

Regarding items related to content, 77.5% of the teachers surveyed answered that they taught new content, but mainly (90.1%) by slowing down the pace of the teaching compared to the previous situation. Considering the topics they taught, teachers were also asked if they had to reduce/soften their depth or extension (Figure 5). Teachers indicated that they had to reduce/soften conceptual content (55.7%), procedural content (41.8%), assessment criteria (60.2%), and, mainly, the number of tasks (67.6%). Of the four referred features, 23.4% of the teachers had to reduce/soften them all.

Figure 5.

Features that teachers reduced/soften during the ERT period.

Regarding the assessment criteria and guidelines, 47.1% of the teachers set or planned to set exams. However, 48.4% still had doubts at the time of the data collection (exams usually take place at the end of May or June, that is, after the application of the research instrument).

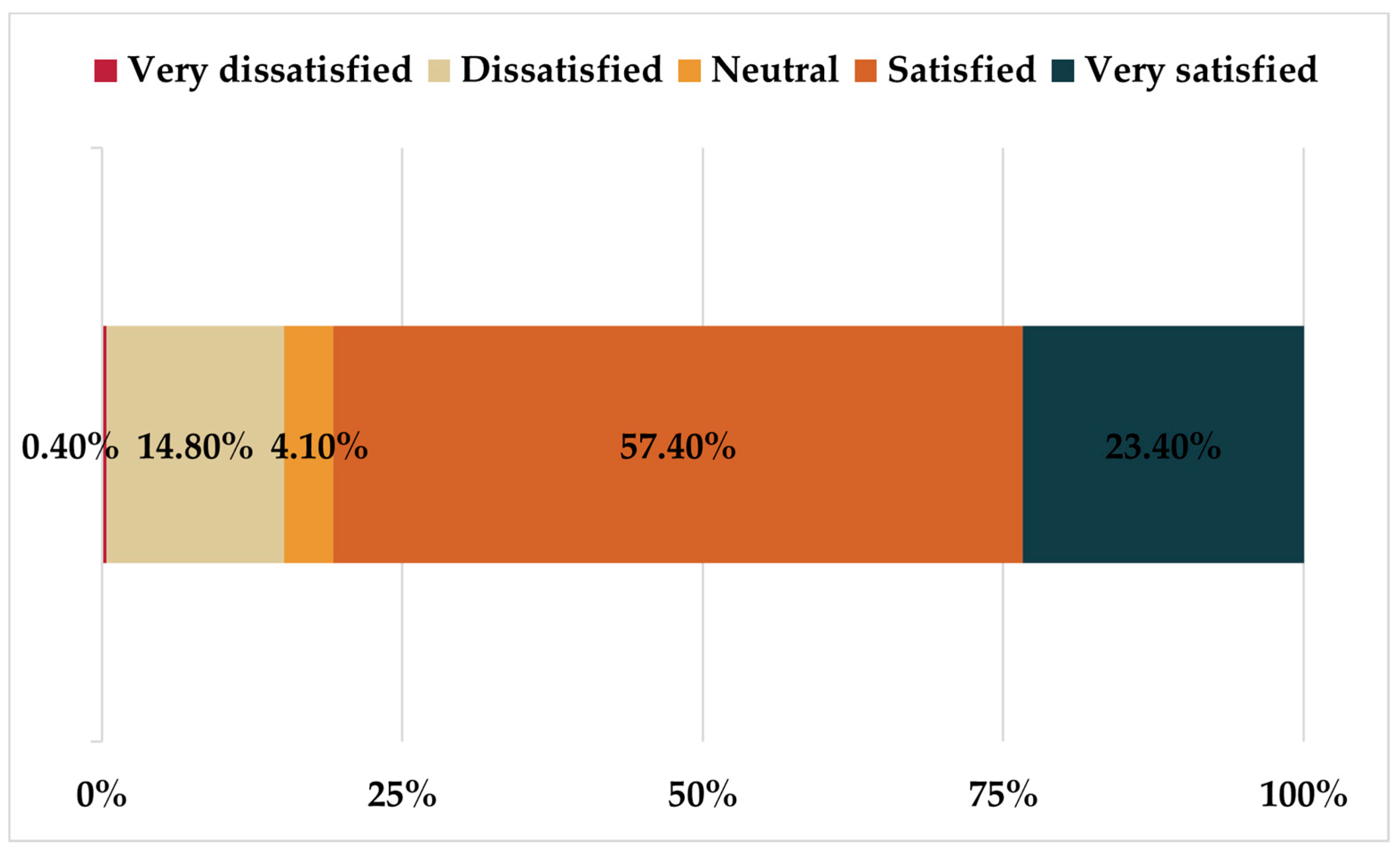

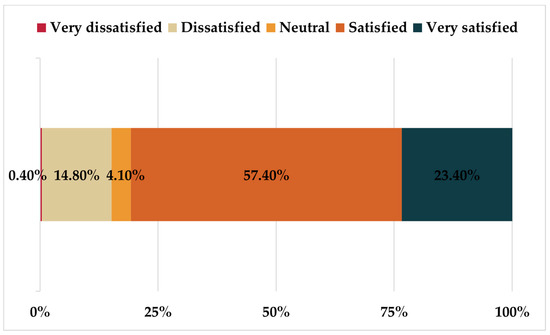

Regarding how difficult it was to adapt to the ERT situation, only 7.8% said it was not difficult, 25% said it was a bit difficult, 43.6% declared it was quite difficult, and 24.6% said it was very difficult. When asked about the comparison between the workload before and during the ERT, 82% of the teachers said they worked much more during the ERT than in normal conditions, 13.5% said a little more, 2.5% the same, and only 1.6% less and 0.4% much less. However, when asked about their satisfaction with the work done during the COVID-19 pandemic, 80.8% were satisfied or very satisfied (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Degree of teachers’ satisfaction with the work done during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.2. Secondary Mathematics Teachers’ Previous Training in Digital Teaching Tools (RQ2)

Almost three-quarters of the participants had received prior training in specific software for teaching mathematics (GeoGebra, Wiris, etc.) and 35.2% had received training for more than 30 h (Table 3), when the pandemic struck. However, around two-thirds of the participants (67.2%) considered they needed more training in these tools. It was also relevant that 59% of the participants agreed that they had received more than 30 h of training in ICT tools (Table 3), although 61.1% of the participants considered they needed more training on this topic.

Table 3.

Training hours in specific software for teaching mathematics and in ICT tools.

3.3. Secondary Mathematics Teachers’ Perception of Their Level of Digital Teaching Competence (RQ3)

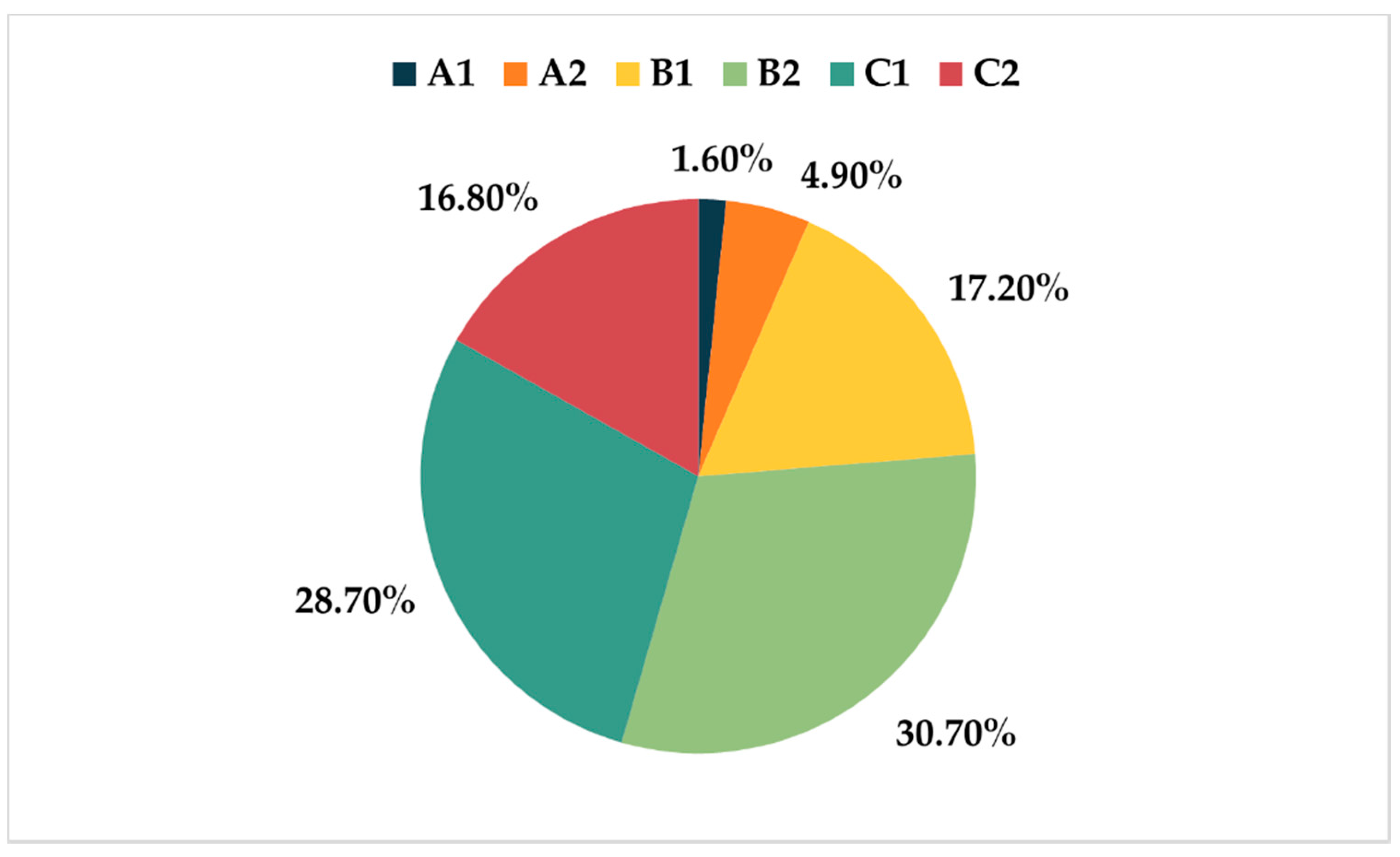

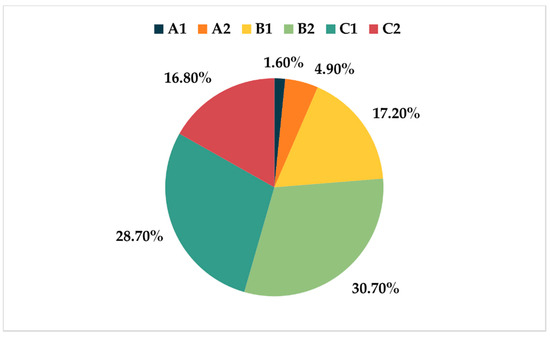

When asked about their perception digital teaching competence according to the INTEF framework, more than three-quarters of the participants classified themselves as intermediate (B2) or advanced (C1 and C2) levels (Figure 7). Moreover, 59.5% of the participants considered that their level of digital competence was rather or totally adequate to face the ERT situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, while 31.6% considered it sufficient, 8.2% quite inadequate, and only 0.8% totally inadequate.

Figure 7.

Distribution of the answers on teachers’ perception their level of digital teaching competence according to the INTEF framework (basic: A1 and A2; intermediate: B1 and B2; advanced: C1 and C2).

3.4. Factors That Influence the Secondary Mathematics Teachers’ Perception of Their Adaptation to the ERT Situation Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic (RQ4)

Statistically significant differences were found in terms of gender in several items of the research instrument. For this analysis, we omitted the option “prefer not to say/nonbinary” due to its low frequency and because its behavior was similar in many cases to some of the other options. Women perceived that their level of digital teaching competence was significantly lower than that of men (MW p-value < 0.000), they needed to learn more different types of editing/processing programs than men (MW, p-value = 0.008), they also considered a greater increase than that of men in their workload during the COVID-19 pandemic (MW, p-value = 0.021), and experienced a more difficult adaptation to the ERT situation (MW, p-value < 0.000). Furthermore, if we consider only teachers who have received training, women received significantly fewer hours of training in specific software for teaching mathematics (CS, p-value = 0.034).

To analyze the differences by age, we reduced the ranges to three in order to correctly apply the Chi-square test. Thus, since 40–49 years old was the original modal class, the ranges finally considered were 20–39, 40–49, and 50–69 years old. Significant differences were found with respect to the following factors. The number of hours of training increased with age, which is obvious since we asked about the training received thorough life. The group 20–39 years old received fewer hours of training in ICT tools (KW, p-value = 0.009), while the other two groups can be considered similar (MW, p-value = 0.539). The perception the increase in workload was lower for the youngest group (KW, p-value = 0.001), teachers between 40–49 years old perceiving the greatest increase.

To analyze the differences by teaching experience, the sample was regrouped into two classes: less than 10 years of teaching experience (24.6% of the individuals) and more than 10 years (75.4%). Despite the fact that both classes were quite unbalanced, we considered 10 years of experience to be a good breaking point due to the changes in ICTs in recent times. As expected, teachers with less than 10 years of teaching experience received less training in ICT tools (MW, p-value = 0.006) and specific software for teaching mathematics (MW, p-value < 0.000), they were less experienced in the use of some of the platforms (CS, p-value = 0.043), they had to learn more about specific software for teaching mathematics (CS, p-value = 0.015), and they had fewer materials ready-to-use or previously collected (MW, p-value = 0.003), than more experienced teachers. On the other hand, teachers with less than 10 years of experience felt they had to put in less effort than more experienced teachers to adapt to the ERT situation (MW, p-value = 0.048).

Regarding teachers’ previous training, the greater the number of hours of training in specific software for teaching mathematics, the more likely it was to use it (CS, p-value = 0.001). Additionally, those teachers who had been trained for more than 30 h in the use of specific software for teaching mathematics considered themselves more digitally competent in teaching according to the INTEF framework (SR p-value < 0.000). Having been trained more than 30 h in ICT tools was also positively correlated with having more ready-to-use or collected materials for remote teaching before the COVID-19 pandemic (SR, p-value < 0.000) and also positively correlated with considering oneself more digitally competent in teaching with respect to the INTEF framework (SR, p-value < 0.000).

Not surprisingly, teachers who considered themselves more digitally competent in teaching also used more different types of resources and editing/processing programs (SR, p-value < 0.000). There was a positive correlation between teachers’ perceptions of their level of digital teaching competence and the percentage of materials developed by themselves (SR, p-value < 0.000), with differences among almost all levels of competence (KW, p-value < 0.000). Teachers’ perception of their level of digital teaching competence was also positively correlated with having ready-to-use or collected materials for remote teaching before the COVID-19 pandemic struck (SR, p-value < 0.000). In particular, there was a negative correlation between teachers’ perception of their level of digital teaching competence (which is intended to increase from A1 to C2) and their perception of the effort to adapt to ERT (SR, p-value < 0.000).

4. Discussion

The results in gender show an image that is quite close to the panorama of Spanish secondary teachers, since there are 61.8% of women in the sample, 61.2% being in the population [38]. Additionally, young teachers (under 30 years old) represent 4.1% of the sample, which is coherent with the population [39].

Teaching practices during the accidental COVID-19 pandemic forced secondary mathematics teachers to expand their TPCK. This finding is consistent with the results of some research studies conducted in other countries under the same circumstances [17,18,40], where secondary education teachers rated their TPCK as average. In particular, in [17], the results of an online survey involving an international sample of teachers pointed out that less than half of the teachers lacked knowledge about remote teaching and communication strategies and tools. Regarding the platforms that teachers used to share educational resources, teach, and/or communicate with students during the ERT situation, we see how email is still prevalent (as noticed in [21,22]), but the emergence of many newer resources that integrate communication tools is also observed (Table 2). This trend is consistent with [22,26], where Google Meet® (Mountain View, CA, USA), Skype® (Palo Alto, CA, USA), WhatsApp® (Menlo Park, CA, USA), or Zoom® (San Jose, CA, USA) were widely used for teaching during this period. In [22], the authors explain that the main reasons behind this decision were the ease of use and the ease of sharing information or communicating with these platforms. The prevalence of email is probably related to the advanced average age of the sample, but it is also interesting to see how teachers began to integrate interactivity with specific educational resources or with other types of software (more than 50% in both cases). Despite the fact that text documents are the most used type of resources, we see (Figure 3) how other formats are gaining importance, such as videoclips and quizzes, which were used by more than 50% of teachers. The data indicate that the shift claimed in [8] from ICT supporting the learning process to ICT integrated into it has occurred for these mathematics teachers before or, at least, during the COVID-19 pandemic [24]. Additionally, embedding interaction into the software also became a relevant teaching practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a consequence, as claimed in [6], students increased their leading role in the learning process. As in [40], we have no evidence to contrast whether or not these uses of software and devices changed the paradigm of teaching through the definition/example/exercise scheme. However, it seems that this paradigm was maintained considering the type of resources and software used by the participants. In summary, the shift towards the use of fashionable educational platforms and resources reflects that teachers’ TPCK is broadened, as this knowledge domain requires that teachers keep up with technological advances [33,34]. The development of teachers’ TPCK and the digital competence for teaching thanks to the ERT is also evidenced by the fact that 40% of the participants were beginning users of some of the platforms or by the fairly high percentage of teachers who developed their own material during this time or needed to learn about editing and/or processing programs. Considering that most of them did not have enough ready-to-use or collected materials that would be usable in a remote teaching environment before school closings and noting that the vast majority made individual decisions regarding the platforms to be used, we can acknowledge that secondary mathematics teachers demonstrated significant TPCK to adapt to the ERT situation. Notwithstanding, according to [17,18,40], the practices of secondary mathematics teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic also pointed to some challenges related to TPCK. Some potential resources for teaching or monitoring student learning are still rarely used (such as applets or blended videoclips and presentations). Therefore, it is necessary to promote greater professional training in this regard.

It is interesting to analyze teachers’ previous training and the perception of their training needs, given their influence on teachers’ TPCK and the level of digital competence. Even though the teachers surveyed showed a large number of hours of training in specific software for teaching mathematics and in ICT tools and perceived that their training should be sufficient to face the situation of ERT, more than 60% of the respondents considered that they still needed more training. Considering the predictive validity of teachers’ knowledge on teachers’ competences [21], the fact that more than three-quarters of the teachers perceived that they have an intermediate or advanced level of teaching digital competence indicates that teachers’ TPCK was quite comprehensive. This finding is also consistent with previous research studies looking at teachers’ digital competence and TPCK before and during the COVID-19 pandemic [6,7,9,40,41]. However, the demands of secondary mathematics teachers in terms of technological training should not be neglected in Spain or in other countries [40]. As previously stated, technology is constantly changing. During the COVID-19 pandemic, all citizens unfortunately experienced how important technology is to continue our daily routines. The latter especially applies to the educational field. Therefore, considering the notable effect of previous training on the level of digital teaching competence and on teachers’ TPCK, it is essential to continue promoting the training and professional development of teachers in terms of ERT [17,25,40]. Taking into account the results of this research study, it seems necessary to reinforce secondary mathematics teachers’ training in video editing and quiz composing, which is also an increasing demand in other contexts [21,26]. As stated in [17], there is also an urgent need for teacher education programs to renew instructional approaches and develop courses that address teaching and learning in online environments.

Although secondary mathematics teachers recognized the harshness of the sudden adaptation to ERT and agreed on the additional workload it entailed, in Spain and also in other countries [17,20], they were highly satisfied with the work done during the COVID-19 pandemic. We understand that most of the problems stemmed from the abrupt transition from the face-to-face teaching to ERT. In [17,18], the authors highlight the reliability of Internet access, personal needs, and unclear or shifting guidelines as some of the most frequently perceived difficulties. Consequently, secondary mathematics teachers were forced to reduce/soften content and to slow down the usual pace of teaching.

Gender differences emerged as a relevant issue. Despite being the majority, women teachers were less trained in ICT tools and specific software to teach mathematics. In addition, they considered themselves less digitally competent in teaching and acknowledged a greater adaptation effort, which may reflect a slight TPCK in women. This is consistent with some previous results within the Spanish framework [42] that found differences in ICT skills between men and women, although different results have been found in developing countries during the COVID-19 pandemic [18]. In any case, our results seem to corroborate the existence of the so-called gender gap in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), which calls for direct interventions from the school years to empower women in the field of ICT [43].

Age is another important factor in terms of adaptation. We found that young teachers received less training but made less effort. Previous studies [44] have shown that young teachers may be considered more competent than older ones in instrumental and ICT skills. Even if we did not find differences regarding their level of digital competence for teaching, the lower effort acknowledged by young teachers to adapt to ERT could mean that they either underestimated their digital teaching competence (and therefore their TPCK) or that older teachers overestimated theirs. Notwithstanding, recent research studies that analyze the situation during the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that belonging to young generations did not guarantee greater digital teaching competence [18,21]. In any case, as we will point out later, the profile of the participants could be limiting the extent of the results, particularly for older teachers.

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a trigger for ERT and a challenge for equity [22]. According to [17,19,23,25], readiness for ERT plays a fundamental role in ensuring the quality of education. In this paper, the secondary mathematics teachers’ perception of their readiness for ERT during the COVID-19 pandemic was analyzed, taking into account their TPCK, their previous training in digital teaching tools, their perception of their level of digital teaching competence, and their perception of their adaptation to the ERT situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic regarding different factors. Thus, we conclude that despite the abrupt transition, secondary mathematics teachers demonstrated adequate TPCK and level of digital teaching competence. Although they were previously trained in terms of different specific software for teaching mathematics and ICT tools, teachers perceived that they need more preparation for remote teaching. This finding supports previous results within the international framework [18,22,40], not only within the mathematics field, but also in other disciplines and educational levels [17,21,45,46,47]. Teacher training, not only in terms of ERT, is essential to guarantee the quality of education. Building on the previous findings, it seems necessary to strengthen secondary mathematics teachers’ TPCK regarding video editing and quiz composing. Their positive attitude towards work and extra effort they made to cope with the situation evidence the teachers’ willingness to continue learning in order to enhance their digital literacy.

One of the contributions of this research study is the finding that despite the differences observed in the hours of training received previously (which were considerably higher in the case of teachers over 40 years old), there are no significant differences in the effort perceived for adapting to the ERT when considering the age of teachers. Undoubtedly, this is related to the high levels of achievement of student teachers’ TPCK during initial teacher education programs in Spain in recent years [41]. In addition, results confirm the gender gap that exists regarding digital teaching competence and TPCK.

The limitations of the study are in the applied sampling techniques and the analysis of a still image of the educational situation at the time of the interruption of face-to-face teaching and the implementation of the ERT. Notwithstanding, this study contributes to the research by showing how secondary mathematics teachers’ TPCK is developing as technology evolves, and it provides evidence about some of the technological teaching practices that have been adopted during the adaptation to ERT. From the situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the educational community has realized the need for continuous training and professional development of teachers in ICT tools in order to ensure their readiness to remote teaching. Along with other studies [6,7,8,9,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26], this research advocates the need to reinforce teachers’ digital competence and TPCK and it provides some hints about which aspects of ICT can be integrated into initial teacher training programs, as claimed in the recent literature [23,24,26,40].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.J.R.-M., D.B. and L.M.-R.; Data curation, L.J.R.-M. and D.B.; Formal analysis, L.J.R.-M.; Funding acquisition, L.J.R.-M.; Investigation, L.J.R.-M., D.B., Á.A.-G. and L.M.-R.; Methodology, L.J.R.-M., D.B. and Á.A.-G.; Project administration, L.J.R.-M.; Resources, D.B.; Software, D.B.; Supervision, L.J.R.-M.; Validation, L.J.R.-M., Á.A.-G. and L.M.-R.; Visualization, L.J.R.-M.and Á.A.-G.; Writing—original draft, L.J.R.-M., D.B. and L.M.-R.; Writing—review & editing, L.J.R.-M., Á.A.-G. and L.M.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (Spain): TIN2017-87600-P.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical review and approval of this study was waived, because it was an anonymous online questionnaire and it was impossible to verify the identity of the participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the collaboration of all the teachers who participated in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Research Instrument

- Age:□ 20 to 29 □ 30 to 39 □ 40 to 49 □ 50 to 59 □ 60 to 69

- Gender:□ Male □ Female □ Prefer not to say/Nonbinary

- Autonomous community in which you work as a teacher:□ Andalusia □ Aragón □ Asturias □ Canary Islands □ Cantabria□ Castile-La Mancha □ Castile and León □ Catalonia □ Ceuta□ Community of Valencia □ Extremadura □ Galicia □ Balearic Islands□ La Rioja □ Community of Madrid □ Melilla □ Navarre□ Basque Country □ Region of Murcia

- Years of experience as a teacher:□ From 0 to 3 □ From 3 to 6 □ From 6 to 10 □ More than 10

- In what year of secondary education do you teach?□ 1st year □ 2nd year □ 3rd year □ 4th year □ 1st year of Bachillerato□ 2nd year of Bachillerato

- What platforms are you using to share educational resources, teach and/or communicate with your students?□ File storage platforms (OneDrive, Google Drive, etc.) □ Blogs □ e-mail□ Mobile messaging □ Videocalling platforms □ Social networks□ Integrate chat, videocalling and file storage platforms (Microsoft Teams, etc.)□ Specific remote learning platforms □ Others: (please, specify)

- Are you using any of these platforms for the first time?□ Yes □ No

- Have you agreed on the platforms you use?□ At the school level □ At the teachers’ level □ At the department level□ They have not been agreed

- How many hours of training in specific software for teaching mathematics (GeoGebra, WIRIS, etc.) have you received?□ 0 □ From 1 to 10 □ From 10 to 20 □ From 20 to 30 □ More than 30

- Do you think you need more training?□ Totally unnecessary □ Quite unnecessary □ Indifferent □ Quite necessary□ Totally necessary

- In general, how many hours of training in ICT tools have you received?□ 0 □ From 1 to 10 □ From 10 to 20 □ From 20 to 30 □ More than 30

- Do you think that you need more training?□ Totally unnecessary □ Quite unnecessary □ Indifferent □ Quite necessary□ Totally necessary

- According to the INTEF classification, what level of digital teaching competence do you have?□ Basic A1 (you need support to develop your digital competence)□ Basic A2 (you have a certain level of autonomy and, with the right support, you can develop your digital competence)□ Intermediate B1 (by yourself and solving simple problems, you can develop your digital competence)□ Intermediate B2 (independently, responding to your needs and solving well-defined problems, you can develop your digital competence)□ Advanced C1 (you can guide other people to develop their digital competence)□ Advanced C2 (responding to your needs and those of other people, you can develop your digital competence in complex contexts)

- I consider that, to adapt to the ERT, my teaching digital competence is:□ Completely inadequate □ Fairly inadequate □ Sufficient □ Fairly adequate□ Completely adequate

- During the ERT period, I have needed to learn how to use editing and/or processing programs to:□ Text editing □ Video editing □ Presentations □ Audio editing□ Image processing □ Infographics □ Quizzes □ None□ Other: (please, specify)

- During the ERT period, did you need to learn to use specific software to teach mathematics?□ Yes □ No

- Of the following resources, please list those that you use to teach or monitor student learning:□ Videocalls □ Videoclips □ Blended videos (Edpuzzle, etc.) □ Images□ Infographics □ Text documents (PDF, Word, etc.) □ Applets□ Presentations (Power Point, Prezi, etc.) □ Quizzes (ThatQuiz, Google Forms, etc.)□ Blended presentations (eXeLearning, etc.) □ Other: (please, specify)

- Considering the materials you have used, how much is your own development?□ None □ Less than half □ About half □ More than half □ All

- Before school closed, did you have ready-to-use or collected materials usable in a remote teaching environment?□ No □ Insufficient □ Sufficient □ Quite a lot □ A lot

- To make your own materials, do you use specific software for mathematics?□ Yes □ No

- Have you taught new content?□ Yes □ No, but I have delved into previously taught content

- Compared to a normal situation, how has the pace teaching new contents been?□ Much lower □ A little lower □ The same □ A little faster □ Much faster

- Regarding the topics taught, what have you needed to reduce/soften?□ Conceptual content □ Procedural content □ Assessment criteria □ Number of tasks

- Have you set or are you planning to set exams?□ Yes □ No □ Maybe

- Regarding the assessment of the third term, do you have clear guidelines and criteria?□ Yes □ No

- How difficult was it to adapt to the ERT situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic?□ Not difficult □ A little difficult □ Quite difficult □ Very difficult

- I consider that, compared to a normal situation, I have worked:□ Much less □ A little less □ The same □ A little more □ Much more

- Overall, how satisfied are you with the work done during the COVID-19 pandemic?□ Very dissatisfied □ Dissatisfied □ Neutral □ Satisfied□ Very satisfied

References

- Sánchez Prieto, J.; Trujillo Torres, J.M.; Gómez García, M.; Gómez García, G. Gender and digital teaching competence in dual vocational education and training. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz-Rodríguez, L.; Rodríguez-Muñiz, L.J.; Alsina, A. The absence of statistical and probabilistic literacy in citizens: Effects in a world in crisis. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, B.; Adams Becker, S.; Cummins, M. Digital Literacy: An NMC Horizon Project Strategic Brief, Volume 3.3, October 2016; The New Media Consortium: Austin, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, G.; Valcke, M.; Van Braak, J.; Tondeur, J. Student teachers’ thinking processes and ICT integration: Predictors of prospective teaching behaviors with educational technology. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz Rodríguez, L.; Alonso, P.; Rodríguez-Muñiz, L.J.; De Coninck, K.; Vanderlinde, R.; Valcke, M. Exploring the effectiveness of video-vignettes to develop mathematics student teachers’ feedback competence. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2018, 14, em1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Guerrero, A.J.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, C.; Gómez-García, G.; Ramos Navas-Parejo, M. Educational Innovation in Higher Education: Use of Role Playing and Educational Video in Future Teachers’ Training. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockendorff, M.; Solar, H. ICT integration in mathematics initial teacher training and its impact on visualization: The case of GeoGebra. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 49, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J.; Van Braak, J.; Valcke, M. Curricula and the use of ICT in education: Two worlds apart? Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2007, 38, 962–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apeanti, W.O. Contributing Factors to Pre-Service Mathematics Teachers’ e-Readiness for ICT Integration. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2016, 2, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba, M.C.; Askar, P.; Engelbrecht, J.; Gadanidis, G.; Llinares, S.; Aguilar, M.S. Blended learning, e-learning and mobile learning in mathematics education. ZDM 2016, 48, 589–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolondi, G.; Ferretti, F.; Gimigliano, A.; Lovece, S.; Vannini, I. The use of videos in the training of math teachers: Formative assessment in math teaching and learning. In Integrating Video into Pre-Service and In-Service Teacher Training; Rosi, G., Fedeli, L., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Pellicer, P.; Giacomone, B.; Burgos, M. Online educational videos according to specific didactics: The case of mathematics. Cult. Educ. 2018, 30, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napal Fraile, M.; Peñalva-Vélez, A.; Mendióroz Lacambra, A.M. Development of digital competence in secondary education teachers’ training. Educ. Sci. 2016, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Sánchez, S.; López-Belmonte, J.; Rodríguez-García, A.M.; López-Núñez, J.A. Teachers’ digital competence in using and analytically managing information in flipped learning. Cult. Educ. 2020, 32, 213–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.; Trust, T.; Bond, A. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educ. Rev. 2020, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chirinda, B.; Ndlovu, M.; Spangenberg, E. Teaching Mathematics during the COVID-19 Lockdown in a Context of Historical Disadvantage. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trust, T.; Whalen, J. Should Teachers be Trained in Emergency Remote Teaching? Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2020, 28, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Almanthari, A.; Maulina, S.; Bruce, D. Secondary school mathematics teachers’ view on e-learning implementation barriers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Indonesia. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. 2020, 16, em1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.Y.; Rajkhan, A.A. E-learning critical success factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comprehensive analysis of e-learning managerial perspectives. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, C.; Holmes, K. An exploration of teacher and student perceptions of blended learning in four secondary mathematics classrooms. Math. Educ. Res. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, J.; Jäger-Biela, D.J.; Glutsch, N. Adapting to online teaching during COVID-19 school closure: Teacher education and teacher competences affects among early career teachers in Germany. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.; Wagner, D. Pandemic: Lessons for today and tomorrow? Educ. Stud. Math. 2020, 104, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, J.; Borba, M.C.; Llinares, S.; Kaiser, G. Will 2020 be remembered as the year in which education was changed? ZDM Math. Educ. 2020, 52, 821–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, J.; Llinares, S.; Borba, M.C. Transformation of the mathematics classroom with the internet. ZDM Math. Educ. 2020, 52, 825–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção Flores, M.; Swennen, A. The COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on teacher education. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção Flores, M.; Gago, M. Teacher education in times of COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal: National, institutional and pedagogical responses. J. Educ. Teach. 2020, 46, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisiones Obreras de Asturias. Situación de la Escuela Pública Asturiana Durante la Crisis del COVID19. Available online: http://www2.fe.ccoo.es/comunes/recursos/15588/2470574-Descargar_informe.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Livingstone, S. Critical reflections on the benefits of ICT in education. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2012, 38, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, J.F. Evolución de la percepción del docente de secundaria español sobre la formación en TIC. Edutec Rev. Electrón. Tecnol. Educ. 2020, 71, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Tecnologías Educativas y Formación del Profesorado. INTEF. Marco Común de Competencia Digital Docente; Instituto Nacional de Tecnologías Educativas y Formación del Profesorado: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Redecker, C.; Punie, Y. Digital Competence of Educators DigCompEdu; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz-Rodríguez, L.; Alonso, P.; Rodríguez-Muñiz, L.J.; Valcke, M. Developing and Validating a Competence Framework for Secondary Mathematics Student Teachers through a Delphi Method. J. Educ. Teach. 2017, 43, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M. Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2006, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, M.J.; Mishra, P. What is technological pedagogical content knowledge? Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. 2009, 9, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.S. Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educ. Res. 1986, 15, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.S. Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1987, 57, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technological Pedagogical and Content Knowledge (TPACK). Available online: http://tpack.org/ (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional. Datos y Cifras. Curso Escolar 2020/2021. Available online: http://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/dam/jcr:89c1ad58-80d8-4d8d-94d7-a7bace3683cb/datosycifras2021esp.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Education at Glance 2020: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew Navarro, C.; Jean Balba, M.; In Kim, J.; Addy Garcia, J.; Exploring Filipino Senior High. School Teachers´ TPACK in Emergency Remote Teaching. Available online: https://easychair.org/publications/preprint/F6K9 (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- Muñiz-Rodríguez, L.; Alonso, P.; Rodríguez-Muñiz, L.J.; Valcke, M. Are Secondary Mathematics Student Teachers Ready for the Profession? A Multi-actor Perspective on Mathematics Student Teachers’ Mastery of Related Competences. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on EUropean Transnational Educational (ICEUTE 2020), Burgos, Spain, 24–26 June 2020; Herrero, Á., Cambra, C., Urda, D., Sedano, J., Quintián, H., Corchado, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1266, pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martín, R.; Castejón-Oliva, F.J.; López-Pastor, V.M.; Fraile-Aranda, A. Evaluación formativa, competencias comunicativas y TIC en la formación del profesorado. Comun. Rev. Cient. Comun. Educ. 2017, 25, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavent, X.; de Ves, E.; Forte, A.; Botella-Mascarell, C.; López-Iñesta, E.; Rueda, S.; Roger, S.; Pérez, J.; Portalés, C.; Dura, E.; et al. Girls4STEM: Gender Diversity in STEM for a Sustainable Future. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de la Iglesia, J.C.; Morante, F.M.C.; Cebreiro López, B. Competencias en TIC del profesorado en Galicia: Variables que inciden en las necesidades formativas. Innov. Educ. 2016, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albó, L.; Beardsley, M.; Martínez-Moreno, J.; Santos, P.; Hernández-Leo, D. Emergency Remote Teaching: Capturing Teacher Experiences in Spain with SELFIE. In Addressing Global Challenges and Quality Education, Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning (EC-TEL 2020), Heidelberg, Germany, 14–18 September 2020; Alario-Hoyos, C., Rodríguez-Triana, M.J., Scheffel, M., Arnedillo-Sánchez, I., Dennerlein, S.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsdottir, G.B.; Hathaway, D.M. We always make it work: Teachers’ agency in the time of crisis. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2020, 28, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Xiao, J. The Emergency Online Classes during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Chinese University Case Study. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2020, 15, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).