3.1. Trend 1: Larger

The elementary and secondary teaching force in the U.S. has increased in size—a trend we refer to as “ballooning.” The U.S. Census Bureau indicates that PreK-12 teachers form one of the largest occupational groups in the nation [

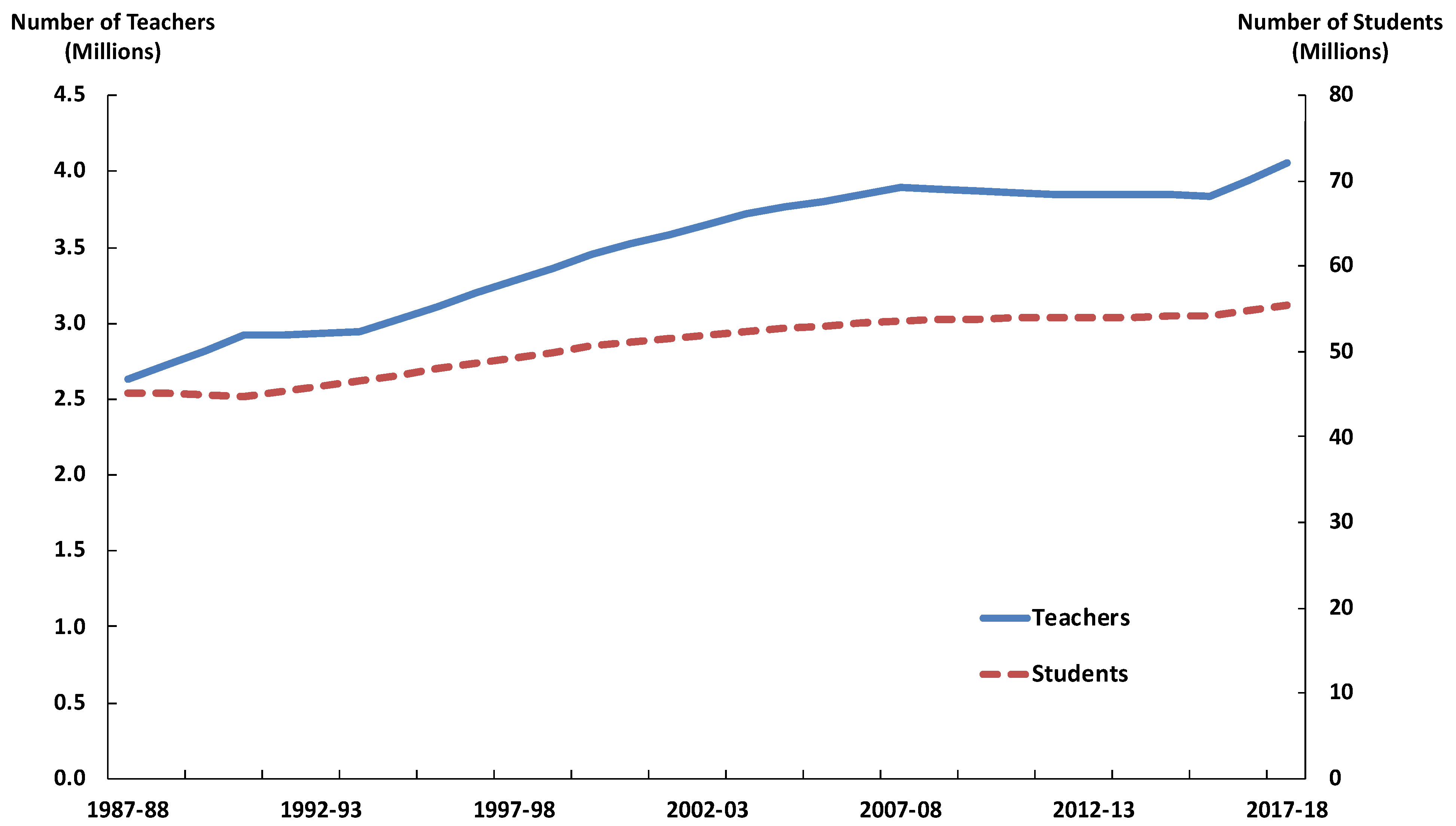

7], and the teaching force is growing even larger. Growth in the numbers of students and teachers is not new. The numbers of both students and teachers grew throughout the 20th century, and the rate of growth for both groups began to soar in the late 1940s with the post–World War II baby boom. Student enrollment peaked by 1970 and then declined until the mid-1980s. During this period, the numbers of teachers also peaked, and then leveled off. In the mid-1980s, elementary and secondary student enrollment again began to grow. Since then, the teaching force has also been increasing in size (see

Figure 1).

The rate of these increases has not matched the magnitude of the baby boom years—with one large difference. In recent decades, the rate of increase for teachers has far outpaced the rate of increase for students—that is, the number of teachers has been going up far faster than the number of students.

As illustrated in

Figure 1, from the late 1980s to 2008, the teaching force increased at a more rapid pace than the student population. Then during the economic downturn after 2008, growth in the teaching force leveled off. Between 2007–2008 and 2015–2016, while the student population slightly increased (by 1 percent), the teaching force slightly decreased (by approximately 1.6 percent). It is unclear how much of this decrease in teachers was due to layoffs or to hiring freezes combined with teacher attrition. After 2016, growth picked up again.

As the top of

Figure 2 summarizes, from 1987–1988 to 2017–2018 total K-12 student enrollment in all U.S. schools went up by 22 percent. During the same period, the teaching force employed in schools increased at over double that rate, by 54 percent. This resulted in a sharp decrease in the overall pupil–teacher ratio in schools.

What accounts for this ballooning of the teaching force between the late 1980s and 2018?

As shown in

Figure 2, the growth in the number of both students and teachers has not been evenly distributed across schools. In the U.S., approximately one-fifth of elementary and secondary schools are privately owned and operated institutions. Approximately one-third of private schools are non-sectarian and the remainder are operated by religious groups. Among the latter, Catholic schools comprise the largest group. Interestingly, the number of teachers employed in private schools as a whole has increased at a faster rate than in public schools relative to the student population (bottom of

Figure 2). But, surprisingly, while the total number of teachers in private schools has increased, the number of students in private schools has decreased. This also varies by type of private school. The three decades from 1987 to 2018 saw a 21 percent increase in the number of teachers employed in Catholic schools, while there was a 27 percent decrease in the number of Catholic schools and a 36 percent decrease in the total number of students enrolled in them. On the other hand, there were increases in the total number of schools, students, and teachers in the non-Catholic religious private school sector and in the non-sectarian private school sector. The overall result has been a sharp decrease in the average pupil–teacher ratio and average class sizes in private schools as a whole, which were already lower than in public schools. However, this increase in private sector teachers and reduction in the student-to-teacher load in private schools does not account for much of the overall ballooning because private schools account only for a small portion of the student population (approximately 8 percent) and of the teaching force (approximately 13 percent).

Growth in the number of teachers was also not even among public schools. The number of students from poverty-level families, and hence who qualify for the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) has dramatically increased over the past three decades (middle of

Figure 2). (The National School Lunch Program is a federal program that offers free and reduced-price school lunches to school-age children from poverty-level families and it is widely used as a measure of the poverty level of students in schools in the U.S.). It is unclear whether this is due to increases in overall poverty, increases in poverty among families with school-age children, or changes in either student applications or the eligibility requirements for the NSLP. But the result is that there have been large increases in the number of high-poverty public schools (defined as those in which three-quarters or more of the students were eligible for the lunch program) and in the numbers of students and teachers in such schools. Over half of the total increase in the number of teachers in public schools during this period took place in high-poverty schools. This group went from 10 percent of all public schools in the period 1987–1988 to over one-third of all public schools by 2017–2018. On the other hand, there have been large decreases in the number of lower-poverty public schools (defined as those in which less than 15% of the students were eligible for the lunch program) and in the numbers of students and teachers in such schools.

Charter schools are publicly funded schools that are granted a greater degree of autonomy from governmental regulations than traditional public schools. They are a relatively new model of schooling in the U.S that have dramatically grown in number over the past couple of decades. But they account for only a small portion of the ballooning of the teaching force because they represent a small segment of all schools (approximately 7.9 percent in the period 2017–2018) and of the teaching force (approximately 5.8 percent).

Another possible explanation for the ballooning is that a reduction in teachers’ workloads—class sizes, hours worked, or classes taught per day—necessitated an increase in the number of teachers employed. For instance, some states, such as California, implemented class size reduction reforms to great fanfare, leading to a demand for more teachers.

On close examination, this explanation does account for part of the ballooning of teachers, but not as much as one might expect. Elementary-level class size did decrease by 18 percent during this period (late 1980s to 2017–2018), from an average of 25.6 to 21 students per general elementary school classroom. Accordingly, the number of general elementary school teachers increased, and because elementary teachers comprise the largest field in teaching—almost one-third of the entire teaching force—their increase explains approximately 27 percent of the ballooning in the school system.

However, in contrast to elementary classrooms, typical subject-area teachers at middle and secondary schools experienced, if anything, increases in their workloads. Average class sizes at these levels went up slightly during this period. The average number of classes taught per day changed little, and, at all grade levels, the average number of instructional hours that teachers work per week slightly increased.

As shown in

Figure 3, there have also been large differences in the growth rates of different teaching fields. In particular, there have been dramatic increases in the number of teachers whose main field was bilingual or English as a second language (ESL), and those whose main assignment was elementary enrichment/elementary subject specialist (these are teachers who teach only one subject, such as art, music, physical education, computer science, or mathematics, to different classes of students in an elementary school). (The increase in teachers in the field of elementary enrichment/subject specialist is from 1990–1991 to 2017–2018. This question was not included in the 1987–1988 SASS.)

It is important to also note that these data on percentage increases in fields do not take into account the relative size of fields and can be misinterpreted if a large percentage increase occurs in a small field, or vice versa. In the case of the above two fields of teaching (bilingual/ESL and elementary subject specialists), while each is undergoing dramatic growth, combined, they remain a small segment of the teaching force, and hence, their rapid increases together account for only approximately 16 percent of the increase in teachers during this three-decade period.

The data also indicate that a significant source of the ballooning has been the growth of the field of special education, likely linked to changes in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, the main U.S. special education legislation. As

Figure 3 shows, the number of teachers whose main field was special education increased by 84 percent, compared to 42 percent for general elementary school teachers. Special education classes average approximately half the size of typical classes in elementary and secondary schools, and special education is a relatively large field (11% of all teachers). Hence, the increase in special education teachers alone accounts for approximately 15 percent of the increase in the teaching force.

As the teaching force has grown, it has also experienced large shifts at the middle and secondary levels during this period. Overall, the number of typical subject-area teachers at the middle and secondary school level has increased by 59 percent. But there has also been a large redistribution of these teachers across fields, with some growing far faster than others. Among those growing the slowest from the late 1980s to 2018 were career/technical education (CTE), art, music, and physical education. Among those growing the fastest, besides special education and bilingual education, were the core academic subjects of English/language arts, foreign languages, mathematics, and science. For example, the number of teachers whose main field was English/English language arts increased by 76 percent. This is one of the largest fields and comprises a variety of subfields, such as literature, composition, reading, and language arts. The number of teachers whose main field was reading increased by 80 percent during this period.

The number of teachers of mathematics went up by 78 percent. The number of teachers of science went up by 84 percent. Although there are two and a half times as many general elementary teachers as mathematics and science teachers, the increase in math and science teachers accounts for approximately 20 percent of the overall ballooning in public schools. A major factor in the growth in the number of mathematics and science teachers appears to be changes in secondary school graduation requirements across the nation. While the number of courses required for graduation went up slightly for English, social studies, and foreign languages, they increased far more for mathematics and science during this period. This change meant that students took more mathematics and science courses. The data show that the number of 9th- through 12th-grade students enrolled in mathematics and science went up dramatically, in turn driving the large increase in the employment of teachers qualified in those subjects during this period.

However, we have not yet uncovered all of the reasons for, and sources behind, the ballooning of the teaching force. One possible set of factors behind the ballooning could be ongoing increases in the number and range of programs, courses, and curricula that schools are required to offer, especially at the secondary level. Educational historians tell us that programmatic expansion has been going on for a century, as schools have continually been asked to take on more and more goals and tasks that were once the responsibility of parents, families, and communities, and as our schools are continually asked to address larger problems and changes of our society and economy [

8,

9](Kirst, 1984; Vollmer, 2010). Indeed, it is important to note that the hiring of more math, science, special education, ESL/bilingual, foreign language, reading, and elementary enrichment/specialist teachers is simply in response to what the public wants. These are fields that have been in high demand.

There are, however, good reasons to further investigate the sources of the rapid growth in the teaching force, given the broad implications. For instance, the expansion of the teaching force, while in response to public demand, and to many of course entirely beneficial, has not been cost free, especially considering that teacher salaries are the largest item in school budgets. To illustrate the overall cost of teacher salaries, we aggregated the base salaries paid to teachers in the 2017–2018 NTPS teacher sample, by teachers’ fields. To give several examples, the total of the base salaries paid to mathematics teachers in the U.S. in the period 2017–2018 was almost $29 billion; for special education teachers, it was just over $26 billion; for physical and health education teachers, it was just over $10 billion; for career/technical education, it was just over $8 billion; and for ESL/bilingual teachers, it was just over $4 billion.

How much has the ballooning itself cost the U.S. in additional teacher salaries? In other words, how much has it cost to hire teachers at a rate beyond what would have been necessary to have simply kept pace with student enrollment increases?

To answer these questions, we undertook an analysis to estimate the increase in aggregate salaries for teachers across the nation due to the ballooning in the number of teachers. Our approximate and conservative estimate is that in the almost three-decade period between 1987–1988 and 2015–2016 the additional aggregate cost of salaries due to hiring more teachers, beyond what would have been necessary to have kept pace with student enrollment increases, was over 40 billion dollars.

Our point is not that ballooning has been unnecessary or excessive or that the additional funds were not well spent. Indeed, having more teachers per students appears to be what the public wants. Our point is simply that the ballooning trend also leaves us with sobering questions: how have school systems been able to cope with such an increase in their largest budget item, who has been paying for it and what will this ballooning mean for the possibility of future increases in teachers’ salaries—as proposed by reformers?

The ballooning of the teaching force also raises related questions regarding the performance and cost-effectiveness of the school system. Economists have long pointed out that, through technological advances, employees in many industries and occupations have become far more productive. A key example is the remarkable changes in agricultural production over the past century—far fewer farmers produce far more produce. Our data raise the question of whether the opposite has been true for teachers. That is, does a decrease in the pupil–teacher ratio mean that teachers have become less “productive”?

A closer look suggests that more teachers per student does not necessarily mean that there has been a decrease in teacher “output”. For instance, a portion of the ballooning is accounted for by the increased demand for, and employment of, bilingual/ESL and special education teachers. These fields appear to require a more intensive teaching process and smaller class sizes. Hence, fewer students per teacher in these fields does not necessarily mean that there has been a decline in the output of teachers.

Moreover, it is important to note that teaching is not the only occupation in which the number of practitioners has been increasing at a faster rate than the client base. For example, data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020) show that the number of nurses, dentists, and pharmacists have all increased in recent decades at a faster rate than the populations they serve [

7]. It is unclear why this has happened, but such increases do not necessarily mean that nurses, pharmacists and dentists are less productive than in the past.

Another implication of the ballooning is for the much-heralded teacher shortages, especially in mathematics and science. We have explored this issue in depth elsewhere [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. As shown in

Figure 3, these have been relatively high-growth fields. Among other findings from our research on shortages, our data analyses show that, contrary to conventional wisdom, the growth in the new supply and employment of qualified mathematics and science teachers has not only more than kept pace with increases in mathematics and science student enrollments, but also with mathematics and science teacher retirement increases—a point we address in Trend 2.

The significant increase in teachers over the past few decades has often been missed or misunderstood by commentators on both sides of the ideological and political spectrum. For instance, some liberal-left economists argued that the economic recession that began in 2008 could have been kick-started into recovery if those teachers who were laid off beginning in 2008 had simply been rehired [

15]. Rehiring teachers as a means to stimulate the economy during the economic recession may well have been a worthwhile initiative. But it is important to recognize that the decline in the size of the teaching force from 2007–2008 to 2015–2016 (see

Figure 1) was modest compared to the ballooning of previous decades. Our data show that the teaching force increased by approximately 1.3 million from 1987–1988 to 2007–2008, but only declined by approximately 64,000 teachers between 2007–2008 and 2015–2016, over half of which were from private schools. In other words, put into a historical context, reductions in the teaching force were neither large nor severe.

On the right side of the political spectrum, some advocates of education reform have cited the ballooning of the teaching force as evidence of “bureaucratic bloat” and “negative productivity” in the public sector [

16,

17]. This view holds that ballooning is evidence of a reduction in teacher productivity—more teachers per students, coupled with little change in test scores. The solution this view espouses is school choice and enhanced competition or privatization, based on the argument that private schools (and charter schools) are in a competitive, market environment, are leaner and more efficient, and hence marked by greater teacher productivity—in other words, they get better student achievement with fewer teachers.

However, these critics overlook the larger ballooning of the teacher force in private schools. Private schools have long had lower pupil–teacher ratios and smaller average class sizes—no doubt in response to what their market and clients want. But, as we show in

Figure 2, it is important to recognize that not only has the teaching force grown faster in private schools than in public schools since the late 1980s, this has happened while the overall number of students in private schools has decreased. In other words, overall, the private school sector has been employing more teachers to serve fewer students. Not surprising, average full tuition at private schools rose 137 percent (after adjusting for inflation) during the 24 year period from 1987–1988 to 2011–2012.

The ballooning of the U.S. teaching force is a dramatic trend, and it is no surprise that a variety of commentators have noticed this trend and have offered explanations for it. However, the reasons for, and implications of, this dramatic growth are still unclear. We hope to address these questions with further research.

3.3. Trend 3: Less Experienced

Graying is not the only change in the age and experience of the U.S. teaching force. Another opposite and unrecognized trend has occurred simultaneously. As

Figure 4 shows, by 2017–2018, the teacher age distribution had spread out, with multiple peaks. As the number of older, veteran teachers increased, so has the number of beginning teachers. The increase in beginning teachers is largely driven by the ballooning trend, that is, by the huge increase in new hires.

Most of these new hires are young, recent college graduates; however, a significant number are older, but inexperienced, beginning teachers. For instance, in the period 2017–2018, approximately 36 percent of new teachers in schools were over age 29, and approximately 15 percent were over 40—the phenomenon often referred to as mid-career switching. This has been fostered by recruitment programs such as Troops-to-Teachers. But mid-career switching into teaching is neither new nor an upward trend. Indeed, despite an increase in the number of older new hires, the current proportion of new hires age 29 or older is little different from that in the late 1980s.

Regardless of their age, these many new hires have resulted in a third trend—a dramatic increase in the number of teachers who are beginners—which we have labeled the “greening” of the teaching force. This trend is illustrated by the distribution of teachers by their years of teaching experience. In the period 1987–1988, the modal, or most common, teacher had 15 years of teaching experience under his or her belt, and the shape of the distribution was a single peak, as shown in

Figure 6. By 2007–2008, the modal teacher was not a gray-haired veteran; he or she was a beginner in his or her first year of teaching. With the advent of the economic downturn beginning in the period 2007–2008 and the subsequent decrease in hiring, which was accompanied by layoffs—usually of beginners [

30,

31]—this greening of the teaching force slowed down. Hence, by 2011–2012, the modal teacher was someone in his or her fifth year. However, with the pickup in hiring, by 2017–2018, the modal teacher was again a beginner—in their first year.

There are, of course, still large numbers of veteran teachers—in the period 2017–2018, approximately one-quarter of all teachers had 20 years or more of teaching experience. But it is useful to recognize that the percentages on greening included above do not take into account the ballooning of the teaching force. Because the teaching force has dramatically grown, numerically there are far more beginners than before. For example, in the period 1987–1988, there were approximately 84,000 first-year teachers; by 2017–2018, there were approximately 300,000 first-year teachers. Similarly, in the period 1987–1988, approximately 1 million teachers (approximately 37 percent of all teachers) had 10 or fewer years of teaching experience; in the period 2017–2018, there were over 1.8 million teachers (approximately 44 percent of the teaching force) with 10 or fewer years of experience.

What are the implications of this trend?

New teachers can be a source of fresh ideas and energy, and it can be beneficial to have new faculty coming into schools. On the other hand, having an increasing number of beginners, along with a decreasing number of veterans, in a school could also have a negative impact. Being taught by more experienced teachers, for example, can make a positive difference for students’ academic achievement. A growing number of empirical studies document what is common sense among those who have taught—that teachers’ effectiveness at improving their students’ test scores usually increases significantly through their first several years on the job [

32,

33]. Beyond academic instruction, as they collect more experience, teachers also have more opportunity to develop many other skills crucial to teaching, such as how to deal with student behavior problems, how to teach students with diverse backgrounds and abilities, how to work and communicate with parents, how to best promote good work habits in students, and how to nurture students’ self-esteem. Having sufficient numbers of veteran teachers in a school can also make a positive difference for beginning teachers. A solid body of empirical research documents that support, including mentoring by veteran teachers, has a positive effect on beginning teachers’ quality of instruction, retention, and capacity to improve their students’ academic achievement [

34].

Greening also has large financial implications for several reasons. First, greening has implications for overall teacher salary costs. A teaching force with an increasingly large portion of beginners at the low end of the pay scale is less expensive, and this could ameliorate some of the increased payroll costs of the ballooning trend mentioned above. For instance, our analyses of the NTPS data show that in the period 2015–2016, the average starting salary for public school teachers with a college degree and no teaching experience was approximately $38,800; while that same year, the average salary for veteran public-school teachers, with over 15 years of experience and a master’s degree, was approximately $66,500.

Second, greening has implications for pension systems. Greening may defray some of the increased pension costs resulting from the graying trend. Economic analysts have been arguing that there has been an alarming decrease in the ratio of new employees who pay into pension systems and Social Security, compared to retired employees who withdraw from pension systems and Social Security [

28,

29]. This imbalance does not appear to be the case for teaching, which is one of the largest occupational groups in the nation. As

Figure 4 and

Figure 6 illustrate, both the proportion and the numbers of younger and less experienced teachers have increased, not decreased.

Moreover, as we will show in Trend 7, early attrition has remained high among this growing number of beginners, meaning that a significant number will never withdraw all of the funds accrued in their school system’s pension plan. In many states it can take 5 to 10 years for a teacher to become fully vested, and hence eligible, upon leaving a school system, to receive any funds contributed by their employers to their pension plan [

35,

36,

37]. In addition, school system pension plans are sometimes backloaded: pension payout levels do not increase evenly with each year of increased classroom experience. Rather, payouts are often relatively small until a teacher has accumulated two or three decades of classroom experience, after which they suddenly jump. High attrition combined with delayed vesting and pension backloading could result in a reduction in payouts from state pension plans, for more detailed discussion, see references [

28,

29].

In sum, greening (along with high attrition) means more of the teaching force is less expensive and more teachers are paying into pension plans, while fewer of them will fully withdraw from pension systems.

3.4. Trend 4: More Female

Educational historians and scholars have documented that when the public school system was created in the U.S. at the end of the 19th century, teaching was intentionally designed to be a predominantly female occupation [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. There were a number of reasons for this, among them were that, since women had fewer other employment options compared to men, and generally paid less, they were less expensive for school districts to employ than men. Moreover, teaching seemed to fit the traditional gender-role stereotype—that women are assumed more naturally suited to child rearing and caregiving than men [

43]. As a result, in this view, historically, in the U.S., K-12 teaching became stereotyped as lower-paid “women’s work”.

For the same reasons, both financial and social, these scholars have held, teaching became less attractive to males. Unlike women, males had more and better-paid occupational options, hence becoming a teacher entailed greater financial “wage sacrifice”, “alternatives foregone”, and “opportunity costs” for males [

44]. Hence, males were less likely to both enter and to stay in the teaching occupation. Indeed, some have concluded that women essentially subsidized the education system for most of the previous century because they were relatively well-qualified employees working for relatively low wages [

43,

45,

46].

However, in recent decades, educational scholars have predicted that this would change as gender stereotypes softened, many occupations became less sex-segregated, and women’s employment options and career opportunities expanded [

47,

48,

49]. Over the past four decades, many occupations and professions that traditionally have been predominantly male have opened up to women. For instance, data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that in 1972, only 10 percent of physicians, 4 percent of lawyers, 2 percent of dentists, and 13 percent of pharmacists were female; by 2019, these proportions had risen to 41 percent (physicians), 37 percent (lawyers), 36 percent (dentists), and 63 percent (pharmacists) [

7]. With career and employment alternatives increasingly available, especially in higher-paid, and/or more prestigious occupations and professions, some have predicted that fewer women would enter lines of work that traditionally have been predominantly female.

Perhaps surprisingly, this has not happened for teaching in the U.S. Both the number of women entering teaching and the proportion of teachers who are female have gone up. The SASS data, along with other NCES data, show that since the early 1980s there has been a slow but steady increase in the proportion of teachers who are female, from 67 percent in the period 1980–1981 to over 76 percent in the period 2017–2018 (see

Figure 7).

It is unclear why this increase has occurred. Here we will offer four possible hypotheses for this increase in the female-to-male ratio in teaching. These hypotheses are neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive.

(1). One possible hypothesis for the increase in the female-to-male ratio in teaching is that teaching has continued to be less attractive and less welcoming to men than women because of the persistence of traditional gender roles and segregation as well as issues with financial rewards, occupational status, and social pressures associated with these roles.

For example, some analysts have argued that males continue to be discouraged from entering teaching due to the persistence of a “wage sacrifice”—as men continue to be able to earn substantially more in other lines of work. For an insightful summary, see references [

49,

50].

Along with financial disincentives, researchers have held that males continue to be faced with a “prestige penalty” if they enter teaching [

51]. The occupational status and stature of teaching has long been a source of both hope and frustration for educational reformers. Historically, during the development of the school system, elementary and secondary teaching was viewed as requiring less ability, skill and training, and in turn, was afforded less pay and less occupational prestige than the well-established professions, such as medicine, law, academia, engineering, dentistry, and accounting. For example, in his classic work,

The Sociology of Teaching, published in 1932, Willard Waller, noted that, “The difficulties of the teacher … are greatly increased by the low social standing of the teaching profession and its’ general disrepute in the community at large … Concerning the low social standing of teachers much has been written. The teacher in our culture has always been among the persons of little importance and his place has not changed for the better in the last few decades” [

52] (pp. 11, 58). Similarly, C. Wright Mills (1951, pp. 129) in his classic study

White Collar published in 1951, referred to schoolteachers as the “proletarians of the professions” in the U.S. [

53] (p. 129).

Not surprisingly, in response, educational reformers have repeatedly sought to promote the view that elementary and secondary teaching is in reality a highly complex kind of work, requiring specialized knowledge and skill, and deserving of the same status, pay and standing as highly regarded professions, like law, academia and medicine. These aspirations have yielded mixed results. Scholars have found that, as far as prestige and status, elementary and secondary teaching in the U.S. lies in the middle—compared with a wide cross-section of occupations and professions. As documented in the General Social Surveys over the past half century the prestige and stature of K-12 teaching has been well below that of professionals, such as doctors, lawyers, professors, dentists and engineers, has been slightly higher than that of the skilled trades, such as plumbers, electricians, and well above that of the lowest status types of work, such as secretaries, waiters and barbers [

54,

55]. However, when compared solely to the subset of white-collar occupations and professions, teaching lies near the bottom, at a similar level as nurses, police, librarians and social workers.

International comparisons of the stature of teachers have also confirmed this finding. In the recent Global Teacher Status Index, teachers were ranked against 14 other white-collar occupations in 35 nations [

56]. On average, teachers’ status was ranked near the bottom of the 14, well below doctors, engineers, lawyers and accountants and only above librarians, social workers and web designers. There were also large differences across nations; China, Malaysia, Taiwan and Indonesia respect their teachers more than other countries, Brazil and Israel were at the lower end of the Teacher Status Index, and the U.S was in the middle.

Given this relative lack of professional legitimacy and prestige, social scientists have argued that the status and social role of teaching has been akin to that of a “semi-profession” in the U.S. [

57,

58,

59]. The persistence of this view may discourage some males from entering teaching.

In addition to financial and status factors, the persistence of social pressures surrounding the gender roles could also be a factor discouraging males from becoming teachers—especially at the elementary school level. An insightful field study conducted over three decades ago found that enduring gender stereotypes made it very difficult for males to teach in elementary schools, despite a strong desire from the public to employ more male teachers in elementary schools [

60]. Male elementary school teachers faced suspicion and distrust, especially from female teachers, who felt that men were simply not suited to work with young children. It is unclear whether such attitudes still persist and it might be illuminating if this study were to be updated and replicated in today’s schools. Interestingly, some recent research has found that socialization factors such as parental influence may be partly responsible for the continued gender homogeneity of the teaching profession, as the children of teachers are disproportionately likely to also become teachers [

61].

However, it is possible the influence of gender roles and their associated financial, status, and social pressures, in dissuading males from entering teaching, has diminished over time. The data show that the increase in the female-to-male ratio in teaching is not due to a decrease in males entering, or an increase in males exiting, the occupation. While the data show that the elementary school teaching force remains overwhelmingly female (89% in 2017–2018), there has been a strong increase (57%) in the number of male teachers employed in elementary schools in the past three decades (

Figure 8). Many of these males are employed as elementary enrichment/subject specialists, a high-growth field (see

Figure 3). Moreover, the TFS data show that there is little difference in the turnover rates of male and female teachers. The number of male teachers employed in schools has grown overall by 29 percent since the late 1980s, which is also faster than the rate of increase in the student population (22%). The increase in the female-to-male ratio in teaching is because the number of females in teaching has increased at over twice the rate of males (see

Figure 8). Rather than males being increasingly “pushed back”, or “pushed out”, it may be that females are increasingly being “pulled into” teaching.

(2). A second possible hypothesis for the increase in the female-to-male ratio in teaching could be a variant of the above mentioned increasing-career-opportunities hypothesis—females have other employment options in general, but also growing opportunities in the educational sector, both at the secondary level and in leadership. The increase in female teachers is not spread evenly across teaching fields, levels and roles within schools. As shown in

Figure 8, increases in the proportion of female teachers have been concentrated at the secondary level, where the majority of teachers were male until the late 1970s. The largest increase in the representation of females in particular fields has been in mathematics and science. In the period 1987–1988, these were both male-dominated fields. By 2017–2018 approximately two-thirds of math and science teachers were female. Moreover, as shown in

Figure 3, these have both been high-growth fields.

As also shown in

Figure 8, there have been far sharper increases in the proportion of female school heads—principals. By 2017–2018, over half of all school principals were female, up from 31 percent in the period 1987–1988, although the distribution of female principals varies by school level, as it does for teachers (see

Figure 9). There has also been a similar increase in females at the position at top of the hierarchy in local educational agencies—school superintendents. Data from the American Association of School Administrators show that, while superintendents remain predominantly male, there has been an increase in the numbers of females holding these positions over the past five decades—from 1.2 percent in 1982 to 27 percent in 2020 [

62].

The trend in female school leaders could be a factor in the recruitment, as well as the retention, of females, including those of high academic ability—an issue we address in Trend 6. Historically, while teaching was designed as a predominantly female occupation, educational administration was designed to be “men’s work” [

38,

40]. Part of the rationale was that the recruitment and retention of capable males in schools required a career ladder with opportunities for advancement and enhancement in status, pay, and authority. Likewise, the contemporary opening up of educational management and leadership to women—demonstrated by the rapid growth in the numbers of female school leaders—could be one possible explanation for the continuing attraction of teaching and education careers for women, despite the growth of other employment opportunities.

(3). A third hypothesis to explain the increase in the female-to-male ratio in teaching might be that the overall proportion of adult women obtaining college degrees, and entering the paid workforce, has dramatically increased over the past four decades. Hence, while women have more job choices than in the past, the large overall increase in women with college degrees and women seeking employment may be partly responsible for the increase in females entering teaching.

Data from the NCES’ Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System show that since the late 1990s over half of college Bachelor’s degrees in any given year are awarded to women [

63]. This is especially the case for degrees in education. In 2018, approximately 43 percent of all Bachelor’s degrees awarded in the U.S. went to males, while only approximately 18 percent of Bachelor’s degrees in education awarded went to males. Moreover, the above cited data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that in a number of specific occupations and professions the number of women has gone up at a faster rate than in teaching [

7].

But the data also show that the number of women in teaching has continued to increase at a rapid rate. The number of women employed in the U.S. labor force overall increased by 36 percent between 1988 and 2016, from 55 million to 74 million. However, the number of women in K-12 public school teaching increased by more than twice that rate during the same period. The proportion of all employed females who were teachers rose from 3 percent to 3.9 percent during the same period. That is, teaching’s share of employed women has gone up, not down, during the same time that the number of women dramatically increased in many male-dominated occupations and professions. It appears that the increase in women in teaching is more than simply a result of more women obtaining college degrees and entering the labor force.

(4). Finally, a fourth possible hypothesis for the increasing proportion of female teachers might have to do with negotiating the dual roles of homemaker and breadwinner—the fit between work-life and family life. Scholars have long held that an important factor behind the high proportion of women in teaching over the past century was the perception of a relatively workable fit between the job of teaching and the work of child rearing [

38,

39,

40,

41,

49]. Compared to many lines of work, teaching has long been characterized as a relatively flexible, easy entry/easy exit/easy re-entry occupation, with fewer career and financial penalties for temporary leaves, such as for raising children [

44,

48,

64]. Moreover, given the perception of a shorter workday and summers off, caring for family was thought to be more manageable for teachers than for those in many other jobs and careers. Given the continuing disproportionate responsibility on the part of women for the domestic labor and childrearing in families [

50,

65], this perceived workday structure may still be disproportionately attracting women to teaching and hence a factor in the increase in the female-to-male ratio. But it is also important to recognize that teaching may not be as amenable to family life as this perception and stereotype holds, given the SASS/NTPS data documenting that teachers in the U.S. typically work more than a 40 hour week and many seek additional employment during the school year and in the summer.

What are the implications of this trend?

One set of questions raised by the data concerns the possible implications for students of the increasing female-male ratio in teaching. If the trend continues, 8 of 10 teachers in the U.S. may soon be female. A large percentage of elementary schools will have few, if any, male teachers. An increasing number of students may encounter few male teachers during their time in either elementary or secondary school. Given the importance of teachers as role models, and even as surrogate parents for some students, certainly some may see this trend as a problem and a policy concern.

Another set of questions raised by the data concerns the implications of an increase in the female-male ratio for the stereotype of teaching as “women’s work” and for the future status and standing of teaching as an occupation. The direction of causality and of the relationships between gender, pay and occupational status are a source of debate, but as discussed above, scholars have long documented that female-dominated occupations are more likely to have lower salaries and more likely to be held in lower esteem than many male-dominated well-established professions [

45,

46,

50,

51,

59,

61]. This raises a troubling question: if teaching continues to become an increasingly female-dominated occupation, would this lead to a further solidification of the stereotype of teaching as “women’s work”, and in turn, make it harder in the future for teaching to improve its pay and its’ status as a respected profession in the U.S.?

3.5. Trend 5: More Diverse, by Race/Ethnicity

While the teaching force is becoming more homogenous gender-wise, the opposite is true for the race/ethnicity of teachers. At first this finding may also seem surprising. For several decades, shortages of minority teachers have been a major issue for U.S schools. It is widely held that, as the nation’s population and students have grown more racially/ethnically diverse, the teaching force has not kept pace. The result, in this view, is that minority students in the nation’s schools increasingly lack minority adult role models, lack contact with teachers who understand their racial and cultural background, and often lack access to qualified teachers of any background, because white teachers eschew schools with large percentages of minorities [

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73]. This minority teacher shortage, in turn, is widely viewed as one of a number of key factors behind the minority achievement gap and, ultimately, unequal occupational and life outcomes for minority students [

74,

75,

76,

77]. In response, in recent decades, numerous government and nongovernment organizations have instituted and funded a variety of programs and initiatives to recruit minorities into teaching. Moreover, often these efforts seek to place these new teachers in schools serving disadvantaged and minority student populations. By 2008, over half of the states had some kind of minority teacher recruitment policies or programs in place. (Throughout this report, we use U.S. Census Bureau classifications of race/ethnicity: “Minority” includes those identified as: Black/African American; native Hawaiian/Pacific/Islander and Asian; Native American/Indian/Alaska Native; Hispanic/Latino; and those of multiple races. “Hispanic/Latino” refers to ethnicity and includes those of all races. Over half of those identifying as Hispanic also identify as White. Hence, the term “person of color” is not synonymous with minority, and, following Census Bureau usage, we will not use the former term.)

However, our extensive analysis of national data show that this portrait is changing [

78,

79]. Our data analyses confirm that teachers remain a primarily White, non-Hispanic workforce and that a parity gap continues to persist between the percentage of minority students and the percentage of minority teachers in U.S. schools. For instance, in the 2017–2018 school year, approximately 40 percent of the nation’s population belonged to minority groups, 51 percent of all elementary and secondary school students were minority, but only 20 percent of all elementary and secondary school teachers were minority (see

Figure 10). Moreover, this gap between percentages of students and teachers holds for each of the main minority groups—Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Native American.

But the data also show that this parity gap is not due to a failure to recruit minority teachers. The gap has persisted in recent years largely because the number of white, non-Hispanic students has decreased, while the number of minority students has increased. The percent of all teachers who belonged to minority groups increased from 12.5 percent in the period 1987–1988 to 20 percent in the period 2017–2018. Growth in the number of minority teachers outpaced growth in the number of minority students and was more than three times the growth rate of white teachers (see

Figure 11). Moreover, during this period, increases in teachers outpaced increases in students for Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians. However, the data also show large differences in the pace of these teacher increases by group. For instance, the number of Black teachers increased by 29 percent, the number of Asian teachers increased by 263 percent, while the number of Hispanic teachers increased by 373 percent [

78,

79].

Moreover, these percentages do not take into account the ballooning of the teaching force. Since the teaching force has dramatically grown, numerically there are far more minority teachers than before. In the period 1987–1988, there were approximately 327,000 minority teachers employed in public and private schools; by 2017–2018, there were over 810,000 minority teachers. Our data also show that the increase in the number of minority teachers has not been even across different types of schools. Most of the increase has been in higher-poverty public schools [

1]. Minority teachers are two to three times more likely than white teachers to work in hard-to-staff schools serving high-poverty, high-minority, and urban communities.

This increase in the number of minority teachers has been something of an unheralded victory. Commentators and researchers have tended to discuss the minority teacher shortage and the outcome of minority recruitment efforts in dire and pessimistic terms. However, although the proportion of minority students in schools is still far greater than the proportion of minority teachers (

Figure 10), the teaching force has in fact grown more diverse. While we have not evaluated the efficacy of particular programs, our data suggest that the widespread efforts over recent decades to recruit more minority teachers and place them in schools serving disadvantaged and minority student populations appear to have made a difference. Moreover, given the continued parity gap, the data suggest that it would be worthwhile to continue such efforts.

However, while minority candidates have entered teaching at higher rates than whites in recent decades, the data also show that the rates at which minority teachers depart from schools is higher, at a statistically significant level, than that of white teachers, and has also been increasing. In the decades from the late 1980s to 2012–2013, the annual rate of minority teacher turnover from public schools increased by 45 percent, undermining minority teacher recruitment efforts [

78,

79]. Indeed, the diversification of the teaching force is all the more remarkable because it has occurred in spite of the high turnover rate among minority teachers. Our data suggest that ameliorating the minority teacher shortage will require focusing on both minority teacher recruitment and teacher retention. We return to the issue of minority teacher turnover in Trend 7.

3.6. Trend 6: Consistent Academic Ability

It has long been held that higher academic achieving college students—“the best and brightest”—are likely to find elementary and secondary teaching less attractive than other career and job options in the U.S. [

19,

44,

47], as well as England [

80]. Over the years, data from different sources have seemed to confirm this. For instance, based on the assumption that academic ability is accurately captured by standardized tests, a number of analyses have shown that the Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT)/American Collegiate Test (ACT) and other standardized college entrance exam scores of college graduates going into teaching have long been well below the average for college graduates [

81]. In our own analyses of national data on college seniors from the NCES’ Baccalaureate and Beyond Survey (in both 1999–2000 and 2007–2008), we found that this was especially true for those majoring in Education, who tended to have among the lowest average SAT scores. Moreover, within most fields and majors, we found that those who became teachers had lower SAT scores than those in the same field/major who did not go into teaching.

Not only do teachers tend to have below-average academic test scores, some researchers and commentators maintain that the academic ability of teachers has been declining over time—and that gender is at the root of the issue. While the number of women going into teaching has increased, as discussed in Trend 4, proponents of this view have argued that the academic quality of women who choose to go into teaching has gone down. With alternative careers and jobs increasingly available, this view holds that the “best and brightest” women have decreasingly entered traditionally female-dominated occupations and professions, such as teaching [

82,

83]. As mentioned, some have argued that women essentially subsidized the U.S. education system for most of the previous century because they were relatively high-ability employees working for relatively low wages. But, the argument continues, this subsidy has stopped, and as a result, the academic caliber of the female portion of the teaching force has declined in recent years [

47,

48].

In the data, however, support for this proposition appears to be mixed. For instance, using longitudinal survey data of birth cohorts from the 1940s to 1990, Bacolod (2007) found that females within the top quintile of standardized test results increased as a share of professionals while decreasing as a share of teachers. Similarly, another study looking at trends in female standardized test scores from the 1960s to 2000 found a decline in the proportion of female teachers who scored in the high deciles [

83]. But another study with data from the Educational Testing Service (ETS) showed no decline in SAT scores of teachers as a whole from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000’s [

84].

Of course, we cannot assume that either the “best and brightest,” or those scoring higher on standardized tests, are the best or the most effective teachers. Accurately measuring both academic ability and teaching quality are subjects of controversy. Moreover, the relationship between them is unclear. But academic ability is often assumed to be an important indicator of both the caliber of employees in any line of work and the attractiveness of an occupation or profession.

We examined these trends using another possible measure of academic ability—the selectivity or competitiveness of one’s undergraduate institution, which is no doubt correlated with SAT/ACT and other standardized college entrance exam scores. The measure we used is Barron’s six-category ranking of colleges and universities: most competitive, highly competitive, very competitive, competitive, less competitive, not competitive [

85]. The top two categories have accounted for approximately 14 percent of institutions and approximately 21 percent of undergraduates. The bottom two categories have accounted for approximately 19 percent of institutions and approximately 13 percent of undergraduates.

What did we find?

Under one tenth of newly hired first-year public school teachers come from the top two categories of higher education institutions. Because in some of the data cycles there is a large amount of missing data on undergraduate institutions for private teachers, for this trend we only report data for public school teachers. Approximately one-quarter come from the bottom two categories. Approximately two-thirds of first-year teachers come from middle-level institutions. From 1988 to 2018 these proportions tended to fluctuate both up and down slightly, but over this three decade period, it appears that there has been a slight overall increase in the proportion of new teachers from the least selective colleges and a slight overall decrease in the proportion from the most selective schools (see

Figure 12).

There are, however, differences in college selectivity by gender. Interestingly, beginning male teachers in public schools have often been slightly more likely to come from top-ranked institutions than have female teachers (see

Figure 13). And, while the levels fluctuated between 1987–1988 and 2017–2018, there appears to have been an overall decrease in the proportion of first-year male teachers in public schools coming from the top two ranks of institutions—from 13 percent in the period 1987–1988, to 10 percent in the period 2011–2012, and to 7 percent in the period 2017–2018.

For first-year female teachers in public schools the proportion coming from the top two categories of institutions has also slightly fluctuated from year to year. There also appears to have been a decrease in the proportion of first-year female teachers in public schools from the top two ranks of institutions—from 2011–2012 to 2017–2018. However, this decrease—from 8 to 6 percent—has been less than for male teachers.

Once again, however, these percentages do not tell the whole story. Although the percentage of female teachers from top institutions has not changed much since the late 1980s, because the teaching force has ballooned (Trend 1) and has also become more female (Trend 4), numerically teaching has been employing far more female candidates from all of higher education, including top colleges and universities.

Hence, assuming our college selectivity measure of academic ability is valid, our data show that there has been a decrease in the proportion of male teachers from top institutions since the late 1980s. But these data also show that this trend has been less true of female teachers. Perhaps we should call the latter a non-trend. So, contrary to the view that there has been a sharp decline in the academic caliber of female teachers, our data suggest that this has not been true in the past three decades.

Along with the increase in the numbers and proportions of female teachers, we do not know the reasons for the apparent stability in the academic ability of females entering teaching in recent decades. As we suggested in Trend 4, perhaps the increased opportunities for women in school leadership and positions in secondary schools (see

Figure 8) have been attractive incentives for able and ambitious females to enter education.

3.7. Trend 7: Unstable

Elementary and secondary teaching in the U.S. has long been marked by relatively high rates of annual departures of teachers from schools and from teaching altogether [

38,

44,

86], and especially in the past three decades, there has been a burgeoning of empirical research on a wide variety of aspects of teacher turnover, mobility, and attrition [

10,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91]. Here we will draw from our own extensive research findings on teacher turnover—especially focusing on trends for beginning teachers.

To contextualize the stability of teachers we empirically investigated how attrition for teachers compares to that of employees in other lines of work, by analyzing national data from the Baccalaureate and Beyond survey on cross-occupational attrition rates of college graduates through their first 10 years after graduation from college. We found that teaching does have less attrition—those leaving the occupation entirely—than some other occupations, such as the child-care, secretarial, and paralegal fields (see

Figure 14). Attrition rates are similar for teachers and police officers. Perhaps surprisingly, teacher attrition is higher than nursing attrition, and teachers have far higher attrition than traditionally highly respected professions, such as law, engineering, and architecture.

But these overall figures mask large differences in departure rates among different types of teachers and different locales, revealing the need to disaggregate our data. The flow of teachers out of schools is not equally distributed across states, regions, and school districts. The largest variations in teacher departures by location, however, are those between different schools, even within the same district. This includes both major components of total turnover—migration (teachers who move between districts and schools) and attrition (those who leave teaching altogether). The data show that almost half of all public-school teacher turnover takes place in just one-quarter of the population of public schools. The data show that high-poverty, high-minority, urban, and rural public schools have among the highest rates of turnover.

Moreover, by analyzing the SASS/TFS data on the demographic characteristics of both the schools migrating teachers move from and also those they move to for the following school year, we have been able to compare the flows of teachers between different kinds of schools. For instance, we found that of teachers who migrated between the 2004 and 2005 school years, over four times as many went from high-poverty schools to low-poverty schools as in reverse. Likewise, of teachers who moved, over three times as many went from urban to suburban schools, as in reverse [

13]. The net result is a large annual asymmetric reshuffling within the school system of a significant portion of the teaching force, with a net loss on the part of poor, minority and urban schools and a net gain to non-poor, non-minority, and suburban schools. For instance, Lankford, Loeb, and Wyckoff offer an insightful examination of teacher migration to and from New York City schools and the suburbs [

92].

The data also show that rates of both moving between schools and leaving teaching altogether differ by the race/ethnicity of the teacher. As mentioned in Trend 5, over the past couple of decades, minority teachers have had significantly higher rates of turnover than white teachers. Moreover, the gap has widened in recent years. Why is this? Strikingly, while the demographic characteristics of schools appear to be highly important to minority teachers’ initial decisions as to where to teach, this appears to be less the case for their later decisions about whether to stay or depart. What does impact their decisions, our analyses show, are school working conditions, in particular the degree of autonomy and discretion teachers are allowed over issues that arise in their classrooms, and the level of collective faculty influence over school- wide decisions that affect teachers’ jobs. The same difficult-to-staff schools that are more likely to employ minority teachers are also more likely to offer less-than-desirable working conditions, according to our data, and these conditions account for the higher rates of minority teacher turnover. These high levels of turnover, of course, undermine efforts to diversify the teaching force [

78,

79].

Beginning teachers, regardless of their race, have among the highest rates of turnover of any group of teachers. Almost two decades ago we estimated that between 40 to 50 percent of those who enter teaching leave teaching within 5 years [

11]. This figure has been widely reported since, but it was only a rough estimate using cross-sectional national data. More recently, using national longitudinal data from the Baccalaureate and Beyond survey, we were able to more accurately document rates of cumulative beginning attrition (see

Figure 15). We found that more than 44 percent of new teachers leave teaching within 5 years of entry.

Moreover, we have also found, despite a temporary dip after the 2008 recession, that high levels of attrition among beginning teachers have been holding steady or even slightly increasing since the late 1980s up to 2012–2013 (

Figure 16). Note: the last cycle of the TFS to be administered was in the period 2012–2013 and it only included public school teachers. Hence, we present turnover data for public school teachers only in

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18.

Again, however, an increase in the annual percentage does not tell the whole story. Because the teaching force has grown dramatically larger, numerically there are more beginners than before (Trend 3), and hence the actual numbers of teachers who quit the occupation after their first year on the job has also increased. Soon after the 1987–1988 school year, approximately 7500 first-year public school teachers left teaching, while just after the 2012–2013 school year, approximately 11,000 first-year public school teachers left the occupation. There are more beginners in the teaching force, and these beginners are less likely to stay in teaching than others.

Along with analyzing TFS data on the rates and cross-school variations of turnover, we also analyzed data drawn from an additional set of items in the TFS questionnaire that asked teacher-respondents to indicate the reasons for their departures from a list in the survey questionnaire. Of first-year teachers who departed from their school after the end of the 2011–2012 school year (including both movers and leavers), one-third indicated that they had been involuntarily transferred, laid off, or terminated (see

Figure 17). This included for both budgetary and performance reasons. A larger portion indicated that family or personal issues played an important part in their decision to depart. This set included reasons of health, pregnancy, a residence move, and caring for family members. Another one-third indicated that they departed to pursue further education or another career. Finally, the most frequently cited set of reasons concerned dissatisfaction. Of those who indicated that dissatisfaction was a major reason for departure, most cited a variety of school and working conditions, including salaries, classroom resources, student misbehavior, accountability, opportunities for development, input into decision making, and school leadership (

Figure 18).

In sum, beginners—the largest group within one of the largest occupations in the nation—have been leaving at relatively high rates, and these rates have held steady or even increased, in recent decades. Together, ballooning (Trend 1) and turnover (Trend 7) indicate a growing flux and instability in the teaching occupation, as both the large numbers of those entering teaching and the large numbers of those leaving teaching have been increasing in recent years.

These changes have large implications. Employee turnover in any occupation has pros and cons, costs and benefits. On the one hand, some degree of employee turnover, with the accompanying job and career changes, is normal, inevitable, and can be efficacious for individuals, for organizations, and for the economic system as a whole. Too little turnover of employees is tied to stagnancy in organizations; effective organizations usually both promote and benefit from a limited degree of turnover by eliminating low-caliber performers and bringing in “new blood” to promote innovation.

On the other hand, high levels of employee departures are consequential not only because they can be a symptom of underlying problems in how well organizations function, but also because departures can entail costs and other negative effects for organizations and for the larger system These include large financial costs [

93,

94,

95], and decreases in student achievement [

96,

97,

98].

As mentioned earlier, we have found that one negative consequence of teacher turnover is its important but often overlooked role in teacher shortages [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Turnover is a major factor behind the problems that many schools have staffing their classrooms with qualified mathematics, science, and other teachers. Moreover, increases in turnover among minority teachers, especially in disadvantaged schools, undermine efforts to recruit new teachers in hard-to-staff schools and to diversify the teaching force. Additionally, research using longitudinal administrative data shows that teacher turnover disproportionately impacts some schools and districts more than others [

99,

100].

As mentioned in Trend 3, a possible financial consequence of high levels of teacher attrition among beginning teachers is a reduction in payouts from state pension plans, because increasing numbers of those who paid into systems remain in teaching long enough to reap full pension benefits.

A further negative consequence of high levels of beginning teacher attrition is the loss of newcomers before they are able to fully develop their skills. As mentioned earlier, a number of studies have documented the reasonable proposition that teachers’ academic effectiveness—as measured by gains in their students’ test scores—increases significantly with additional experience for the first several years in teaching [

32,

33].