What Can We Learn about Science Teachers’ Technology Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Willingness to Use Technology

1.2. Frequency and Variety in the Use of Technology

1.3. What Makes Technology Difficult to Use?

1.4. The Present Study

- Which groups of teachers can be distinguished based on the teachers’ descriptions of their technology use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic based on three aspects:

willingness to use technologychange in technology use from pre-COVID to distanced learning, andvariety in the use of technology?

- 2.

- How do the perceived obstacles of technology use differ between groups of teachers?

2. Methods

2.1. Context and Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instrument

2.4. Data Analysis

- Regarding the integrity of the data: interviews were prepared and conducted by the authors of the current paper; authors had a consensual agreement in interpreting data; all interpretations are exemplified with direct quotes from teachers’ answers; 4 out of 12 interviews were co-analysed by the authors of the study; any differences in coding were discussed and a common agreement was reached; these interviews were used as referents for the other cases, if needed, to find the relative positioning of the remaining cases; as the interview was in Estonian, all quotes were subsequently translated into English;

- in terms of the balance between reflexivity and subjectivity—in order to check the meaning of the answers given we asked reflective questions during the interview;

- pertaining to the clear communication of findings: all analyses are interpreted and compared with findings from other studies.

3. Results

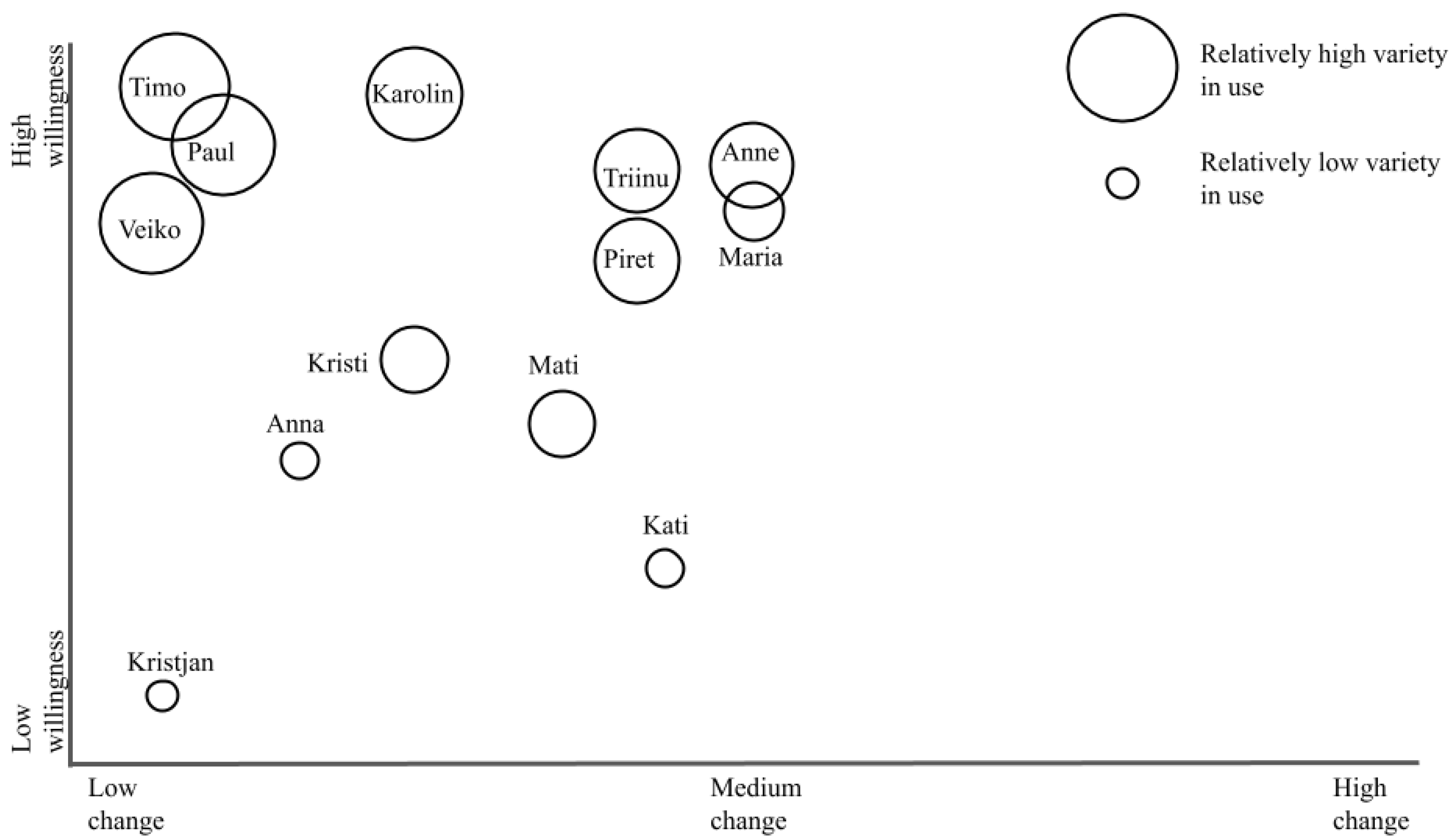

3.1. Teachers’ Willingness, Change, and Level of Technology Use

3.1.1. Teachers with High Willingness (Timo, Paul, Karolin, Triinu, Maria, Anne, and Piret)

“I was a frequent user already before the crisis and I can say that this has increased during the current situation.”(Piret)

“It was quite a challenge, but not very scary.”(Maria)

“I am very much pro-technology; I enjoy it when a solution works very well. But we also want to do things in real life.”(Karolin)

“I’m aware that it takes more time to prepare lessons, but I’m making efforts to keep pushing at my own pace … technology is motivational and brings excitement to the students.”(Anne)

3.1.2. Teachers with Low Willingness (Kristjan and Kati)

“Right now, this digital and distanced learning is still unknown/unusual.”(Kristjan)

“I still lean towards the principle that in science subjects (students) should get to do more real experiments and that videos are supportive material.”(Kati)

3.1.3. Teachers with Medium Willingness (Anna, Kristi, and Mati)

“I have never been hostile (towards technology), but now it was a bit more difficult …”(Anna)

“I know there are so many interesting things, but I haven’t had the time to make them work for me and haven’t had that now either.”(Kristi)

“I did not get any braver and will not do things differently than I used to (after the distance teaching).”(Anna)

“I look with envy at how already, only a few days later, younger ones (colleagues) are already working in Classroom (authors’ note: program Classroom) and have made their videos with smartphones.”(Mati)

3.2. Technology Use: Change in Behaviour and the Level of Technology Adoption

Change in Technology Use

“The use of technology (in the classroom) was rising (before the lockdown); however, now it is absolute.”(Timo)

- Low change (Timo, Paul, Karolin, Kristjan, Anna, and Kristi)

“A teacher in a state of emergency is still a teacher.”(Timo)

“There is not much difference when it comes to the environments that I use.”(Anna)

“I haven’t had the need to work in anything new (referring to the environments used for teaching), besides Zoom.”(Kristi)

“I use about 18 different technological solutions.”(Karolin)

“I give more individual feedback on independent work. Before, I didn’t give feedback on every step.”(Kristi)

“With some sentences in the e-school, I give instructions on which pages to go through, to which questions to pay extra attention. … Otherwise in the classroom there was oral answering, reporting/answering in front of the class.”(Kristjan)

“Now, the focus is more on which tools we can use to work together or what they can use for that …”(Timo)

“Before, I checked (Messenger or emails) once a day … and I did not … answer right away … now, when I read it, I answer right away.”(Anna)

“For me, it was nothing new. I have experience of online teaching, I have prepared e-learning materials and conducted video lessons.”(Veiko)

- Medium change (Kati, Mati, Piret, Triinu, Anne, and Maria)

“Everything had to be redone/adapted to a digital version.”(Maria)

“For me it has changed substantially. … Some things we watched before, simulations, videos which connected to physics. But the thought that we have some real things to deal with (authors’ note: in the classroom, referring to experiments and discussions in the classroom).”(Kati)

“(The distanced learning situation) forced me to work on things, to work on things that I was thinking of using, but …”(Maria)

The teachers also said that even though they had some things “worked in” at the time of the interviews some weeks into the distanced learning period, it takes time.

“Now we have agreed upon which environments we use. Learning new things takes time.”(Mati)

Additionally, teacher’s described the maintaining of students’ motivation as a reason behind their decision use more technology than before the COVID-19 pandemic.

“For me, technology carries the motivational aim … students do not like to just fill in worksheets.”(Anne)

3.3. The Level of Technology Adoption during the COVID-19 Pandemic (How Teachers Described the Aims of Using Technology)

3.3.1. Enhancement-Focused Adoption (Substitution and Augmentation) (Anna, Kati, Maria, Kristjan, and Kristi)

- Instructing

“They send it (referring to a photo of a textbook page) to my email … and I send it back with my evaluation or comment.”(Kristjan)

“I started using Socrative … now instead of the (open-ended questions) test we do with a multiple-choice test. … Most of the time goes to giving feedback.”(Maria)

In some cases, teachers described how technological solutions set some limitations on giving instructions and controlling processes, indicating that during their usual teaching practice they would have performed their task differently. As one teacher indicated,

“Testing is done more in the multiple-choice test format. … We have less of these longer exams where they had to verbalize (their answers).”(Kristi)

- Communicating

“Children do not read emails or pick up their phones. … Now I am accessible all the time. … I need to be on social media all the time.”(Maria)

- Sharing materials

“They take a photo of page 14 (referring to the textbook) for which they have read the theory from the book.”(Kristjan)

“e-õpik (collection of electronic textbooks and workbooks), where I ask students to read the textbook and fill in the workbook”(Anna)

“To explain the topic further, there are some video clips or a link to an e-textbook.”(Kati)

3.3.2. Transformation-Focused Adoption

“With the worksheets in Wiser, they can check themselves if they are correct. With the workbooks this doesn’t happen, maybe they wait until the teacher collects (the workbooks) … and then get to know (the right answers), but now they get (them) right away.”(Karolin)

“Google slides where you can work on something together, rearrange pictures.”(Timo)

3.4. Perceived Obstacles to Technology Use for the Three Groups of Teachers

3.4.1. Overlaps Common for all Three Groups

- Infrastructure

“All students do not have the means. It is assumed that they would, but they still do not.”(Karolin)

“Some have poor internet. … Some have only one computer for the whole family … there are still a few with these problems.”(Maria)

“We heard about some (families) that were lent a computer.”(Anna)

- Feedback

“It is more of a mystical and dark territory (how the student reacts and if they are listening), which makes it also more difficult to adapt the tasks to the specific needs of the student in that situation.”(Timo)

“I see that everything is filled out (referring to students’ work); however, I don’t see the state (of the student) behind.”(Karolin)

- Students’ digital skills

“I have chosen environments where I know that they have acquired (the skills) already.”(Timo)

“There are (students) who will never start wanting (to try to figure out environments) and those who can’t.”(Karolin)

“Give them a file and they can’t use the speller. They know certain things, things that you wouldn’t even think of.”(Maria)

“There are so many environments, to consider when thinking about which one the student can manage (on her own) at home.”(Anna)

3.4.2. Overlap between Group B and Group C

- Time-consuming for the teacher

“It takes time to learn how to use (different solutions), after that it’s useful.”(Mati)

“Making videos is extremely time-consuming, I cannot make a video for them for every class.”(Maria)

“Revising is time-consuming, there are no easy, simple solutions for revising (referring to the lack of technological solutions).”(Mati)

Time was also an obstacle in cases where the teacher saw that in the usual teaching situation reliance on a colleague made the preparation time was less costly.

“I’m ready for the technology, but it takes more time for me to prepare materials … at home, I don’t have colleagues who can help … before it was easier.”(Anne)

- Students’ study skills

“The biggest difficulty is that (students) lack the skills to work on their own with the textbook.”(Kristjan)

“More self-discipline is needed, how do I focus on this, how long it takes …”(Maria)

“I have to give things in smaller chunks. In the classroom, I would go through everything in one lesson, now it takes two lessons. … Plus, we don’t leave homework, as they do everything at home.”(Kati)

3.4.3. Distinctive Obstacles for the Three Groups

“The problem is not technology but distance. We do not know and can’t evaluate what the situation is (for the student), if they have a place to focus …”(Timo)

- Limitations of technological solutions

“If I don’t have the energy to look that much to pay to find the best solutions for my needs. … There are not many environments or I don’t know how to find them. I want more complex environments.”(Karolin)

- Too many solutions in use in parallel

“Now all schools are mixed up for me. Earlier I was quite precise with school days (e.g., on Wednesday I’m at one school and on Friday I’m at another school) and I had a clear system. This made it easy to keep track, but now I’m not moving physically from one school to another. Now students contact me at a random time, so I always have to first understand which school, which platform.”(Veiko)

“I asked students to take part in a forest quiz … basically, it meant that I had to manually insert students name by name … at some point, I thought I would stop, but as I had already added the task description in the e-school, I did finish adding the names of more than 100 students … it took time.”(Triinu)

- Difficulties with technological solutions

“I live in an apartment building, and the internet can just stop working at one point during the day … there are five class sets of students on the call.”(Kati)

“They (referring to students) cannot use it very well. First of all, you need to teach how, where and then you learn yourself alongside it.”(Kati)

“One parent was even upset that so much work is on the computer. … The students may sit there for 30 min, but when checking (student work), the teacher is there longer … this is tiring for the eyes.”(Kati)

- Teachers’ attitudes and beliefs

“I have thought (about using Zoom) but the system that I use … I am happy and students are happy … they are used to sending me the worksheets (authors’ comment: pictures of worksheets on paper) on time.”(Kristjan)

“I took the position (before COVID-19) that as technology is used in many subjects anyway, then in science classes we do ‘real things’.”(Kati)

4. Discussion

- Similar to previous studies on willingness and technology use [6,7,8], we observed based on teachers’ descriptions a rather clear connection between willingness and technology use and integration level. Teachers who reflected higher willingness to use technology also described more technology integration within their teaching (before and after the COVID-19 pandemic) and were more likely to be working on the transformational level with this integration. However, when it came to willingness and change in technology use, this relationship was not as straightforward.

- It is essential to consider that the lack of change in the usage behaviour from pre-COVID-19 to the COVID-19 pandemic might not reflect the extent to which teachers use technology in their work. Teachers with relatively high willingness described frequent technology use already before the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, the change in their technology use was rather low. On the other hand, several teachers whose willingness was relatively low gave a similar description of their technology use during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we observed that within the medium willingness group the change in technology use from classroom teaching to teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic was quite diverse. Based on this, it could be argued that the impact the distanced teaching situation on the use of technology [23] may vary across the levels of willingness to use technology. To gain more insight into what may inhibit different groups of teachers from adopting technology in their teaching practices, we focused on the kinds of obstacles emerging from the descriptions given by the teachers in these three groups.

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Implications for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- What does it mean to be a teacher working under distanced learning conditions?

- What are you doing differently in your teaching compared to the period before the distanced learning?

- What has been the biggest change in preparing the lessons; in conducting the lessons; and in giving feedback to the students.

- What role does technology play in your current lessons? How does it differ from before?

- What kind of technology do you usually apply to your lessons?

- What are the main goals of using technology in your lessons during distanced learning?Give some examples.

- What are the main obstacles to using technology under distanced learning conditions?

- What is positive about using technology under the conditions of distanced learning?

- Does distanced learning change your attitude to technology?

- What were the main goals of using technology in your lessons before distanced learning?

- Age

- Years taught

- Subject(s) taught

References

- Scherer, R.; Teo, T. Editorial to the special section—Technology acceptance models: What we know and what we (still) do not know. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 50, 2387–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adov, L.; Pedaste, M.; Leijen, Ä.; Rannikmäe, M. Does it have to be easy, useful, or do we need something else? STEM teachers’ attitudes towards mobile device use in teaching. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2020, 29, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Spoel, I.; Noroozi, O.; Schuurink, E.; van Ginkel, S. Teachers’ online teaching expectations and experiences during the Covid19-pandemic in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabakçi-Yurdakul, I.; Ursavas, Ö.F.; Becit-Isçitürk, G. An Integrated Approach for Preservice Teachers’ Acceptance and Use of Technology: UTAUT-PST Scale. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.; Siddiq, F.; Teo, T. Becoming more specific: Measuring and modeling teachers’ perceived usefulness of ICT in the context of teaching and learning. Comput. Educ. 2015, 88, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.; Siddiq, F.; Tondeur, J. The technology acceptance model (TAM): A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach to explaining teachers’ adoption of digital technology in education. Comput. Educ. 2019, 128, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.; Siddiq, F.; Tondeur, J. All the same or different? Revisiting measures of teachers’ technology acceptance. Comput. Educ. 2020, 143, 103656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adov, L.; Pedaste, M.; Leijen, Ä.; Rannikmäe, M. Moving from intention to behaviour: Predicting teachers’ mobile device use for teaching. (submitted).

- Tsybulsky, D.; Levin, I. Science teachers’ worldviews in the age of the digital revolution: Structural and content analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 86, 102921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M.; Mezhuyev, V.; Kamaludin, A. Technology Acceptance Model in M-learning context: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2018, 125, 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kippers, W.B.; Poortman, C.L.; Schildkamp, K.; Visscher, A.J. Data literacy: What do educators learn and struggle with during a data use intervention? Stud. Educ. Eval. 2018, 56, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hatlevik, O.E.; Ottestad, G.; Throndsen, I. Predictors of digital competence in 7th grade: A multilevel analysis. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2014, 31, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transformation, Technology, and Education. Available online: http://hippasus.com/resources/tte/ (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D. Mobile learning and pedagogical opportunities: A configurative systematic review of PreK-12 research using the SAMR framework. Comput. Educ. 2020, 156, 103945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuni, S.; Mujiyanto, J.; Dwi, R.; Fitriati, S. Teachers’ Technology Integration into English Instructions: SAMR Model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Science, Education and Technology (ISET 2019), Semarang, Central Java, Indonesia, 29 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowman, M.A.; Vongkulluksn, V.W.; Jiang, Z.; Xie, K. Teachers’ exposure to professional development and the quality of their instructional technology use: The mediating role of teachers’ value and ability beliefs. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaseva, A.; Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt, P.; Siibak, A. Relationships between in-service teacher achievement motivation and use of educational technology: Case study with Latvian and Estonian teachers. Technol. Pedagog. Inf. 2018, 27, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J.; Roblin, N.P.; van Braak, J.; Voogt, J.; Prestridge, S. Preparing beginning teachers for technology integration in education: Ready for take-off? Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2017, 26, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.N.; Morrow, S.L. Achieving trustworthiness in qualitative research: A pan-paradigmatic perspective. Psychother. Res. 2009, 19, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, W.S.; Han, I.; Kim, I. Teachers’ Technology Use and the Change of Their Pedagogical Beliefs in Korean Educational Context. Int. Educ. Stud. 2014, 7, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrell, S.; Bynum, Y. Factors Affecting Technology Integration in the Classroom. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 5, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Ritzhaupt, A.D.; Dawson, K.; Barron, A.E. Explaining technology integration in K-12 classrooms: A multilevel path analysis model. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2017, 65, 795–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant (Pseudonym) | Working Experience as a Teacher | Subjects |

|---|---|---|

| Anna (female) | 3 years | Science and Geography |

| Kati (female) | 2 years | Science and Physics |

| Kristi (female) | 7 years | Science and Chemistry |

| Mati * (male) | 30 years | Physics |

| Karolin (female) | 10 years | Biology and Science |

| Maria (female) | 20 years | Biology |

| Timo (male) | 4 years | Science |

| Kristjan (male) | 64 years | Physics and Science |

| Triinu (female) | 16 years | Biology, Geography, Science |

| Veiko (male) | 20 years | Biology |

| Paul (male) | 17 years | Physics and Chemistry |

| Anne (female) | 34 years | Biology |

| Piret (female) | 35 years | Biology |

| Groups | Shared Obstacles | Distinctive Obstacles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A: Timo, Karolin, Paul, and Veiko | Problems with infrastructure Problems with giving immediate feedback | - | Limitations of technological solutions Too many solutions in use in parallel |

| Group B: Triinu, Anne, Maria, and Piret | Time-consuming for the teacher Students’ study skills | Difficulties with external learning materials | |

| Group C: Kristjan, Kati, Anna, Mati, and Kristi | Difficulties with technological solutions Teachers’ attitudes and beliefs | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adov, L.; Mäeots, M. What Can We Learn about Science Teachers’ Technology Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11060255

Adov L, Mäeots M. What Can We Learn about Science Teachers’ Technology Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Education Sciences. 2021; 11(6):255. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11060255

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdov, Liina, and Mario Mäeots. 2021. "What Can We Learn about Science Teachers’ Technology Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic?" Education Sciences 11, no. 6: 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11060255

APA StyleAdov, L., & Mäeots, M. (2021). What Can We Learn about Science Teachers’ Technology Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Education Sciences, 11(6), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11060255