1. Introduction

The California State University system, the largest four-year public university system in the United States, was among the first to call for an immediate transition to online learning in Spring 2020 across the whole 23-campus system. It was also the first system across the country to announce that both the Fall 2020 and Spring 2021 semesters would remain primarily online, with limited hybrid course offerings. These early decisions prompted a group of faculty members in the College of Engineering (COE) at SJSU to survey students and faculty members to better understand their experiences as a result of the sudden shift to online learning due to the shelter-in-place order, with the intent to better prepare for Fall 2020 and Spring 2021 online instruction. The rapid switch to online instruction in March 2020 did not allow faculty members to train, plan, and reflect upon the best teaching modes for online instruction, unless they had previously taught an online class. Therefore, as with many other researchers [

1], we consider the Spring semester to be an example of emergency remote learning rather than planned online learning.

Online education (also called online learning, remote learning, distance learning, or e-learning) has grown in popularity across the U.S. over the last 10+ years, with increased online options across all universities, including public, private, non-profit, and for-profit institutions. Online learning is defined as education that takes place online, either synchronously and/or asynchronously. In Fall 2018, approximately 35% of undergraduates in U.S. two and four year colleges took at least one online course [

2].

One consistent factor for effective online learning is the recognition that quality online education requires careful and effective design, delivery, and assessment that goes beyond shifting in-person practices to an online environment. The need for high quality online education tools is greatest when student populations are underserved or at-risk, including students who are low-income, first-generation, and persons of color [

3] The students of the College of Engineering and SJSU are diverse, with a significant number of students identified as one or more “at-risk” markers including first-generation college students, low-income students, and underrepresented students.

Table 1 presents demographic data for SJSU and the College of Engineering.

Online course offerings are an important component of higher education. However, online education, similar to other major transitions in higher education, has been met with resistance from instructors [

5]. Administrators who promote online education are accused of prioritizing cost over quality, student outcomes, and faculty expertise [

6]. In engineering, there are few online courses or degrees available in the U.S.; however, online engineering courses are more available at the graduate level.

Online instruction, which has grown in popularity in the last decade in the US, requires thoughtful instructional design, delivery, and assessment. Online instruction is different from teaching in-person and requires skills and expertise that are generally not part of faculty members’ education and experience. Use of technology, which is of paramount importance in online instruction, can be a barrier to some of the faculty members.

Generally, online learning comprises of a combination of synchronous (real-time) and asynchronous learning (on-demand). Most common pedagogies in online teaching include discussion boards, audio and video submissions, text-based assessment, collaboration, emails exchanges, text-based chat, audio and video conferencing, real-time polls, real-time collaboration, and real-time assessment [

7,

8]. These teaching modes can be classified as “surface structures” (pedagogies that transmit the information between the teacher and students), “deep structures” (pedagogies that encourage higher order thinking and problem-solving), and “implicit structures” (pedagogies that develop a moral dimension in terms of professional values and attitudes). According to Eaton et al. [

7], some teaching activities in the online environment have “the potentials to cultivate deeper learning experiences, but they can fail to do so if activities are not designed and implemented properly”.

Since the emergency move online in Spring 2020, there have been several surveys of faculty to ask them about their experiences. The Higher Education Data Sharing Consortium (HEDS), in their survey of faculty, received responses from 4000 faculty from 28 different colleges [

9]. The faculty felt overwhelmed in Spring 2020 by the increased amount of work in the newly online classes, with 61% of faculty indicating they had too many things to do, 55% felt that they were in a hurry, and 51% felt under pressure from deadlines.

A second survey of university faculty in Spring 2020 was done by Tyton Partners, in conjunction with Every Learner Everywhere [

3]. Nearly 5000 faculty from over 1500 institutions responded. This survey found that almost all faculty (91%) had to move online in Spring 2020 because of COVID-19. Fewer than half of the faculty had ever taught online. The Tyton study also found that faculty had difficulties in engaging and motivating their students after the move online. Faculty also indicated that child or elder care was a significant challenge for 40% of faculty, with women and tenure-track faculty more likely to report this concern. In addition, research indicates that many faculty had technical issues after the move online [

10], such as lack of reliable internet connection, no access to a webcam or camera for use during online instruction, and no access or technical difficulties with online writing tools.

Faculty challenges with the emergency remote learning include a decreased interaction with students during class time and decreased students’ engagement [

11,

12], increasing concerns about students well-being [

13], and a general feeling that their course quality has decreased [

12]. In addition, faculty members needed to juggle work with personal needs. Some of the strategies that faculty members adopted to adapt to the remote environment include modifying or dropping assignments and exams and lowering their expectations about the quantity and quality of the work performed by the students [

14]. Despite the challenges, according to Williams [

12], faculty members had a positive experience in teaching remotely in Spring 2020.

Almost all faculty members in the United States were required to shift their pedagogy in Spring 2020, in what has probably been the quickest shift in teaching pedagogy that the academic environment ever experienced. In order to understand the underlying assumptions that drove faculty members in re-evaluating their teaching practices and adapting them to the remote environment at the end of the Spring 2020 semester, Deters et al. [

15] conducted semi-structured interviews of three mechanical engineering faculty members and eight students. This study identified three main core beliefs that motivated faculty members’ decision: fear of cheating, valuing of hardness, and views on flexibility. The personal challenges that faculty members experienced likely influenced their ability to effectively shift their pedagogy and testify to the resilience of the faculty body. Morelock et al. [

16] created a novel research platform to collect the experience of students, faculty members, and staff (for a total of 70 participants, of which 25 were faculty members). The study identifies that students and instructors struggled to recover a sense of connectedness in a remote environment, as well as a disconnect between faculty members’ and students’ experiences. Students and faculty members faced a range of COVID-19-related challenges within and outside of academia.

There also has been increased stress reported by faculty after the move online because of COVID-19 [

17,

18,

19]. For example, Bizot et al. [

19] found that over half of the computer science faculty who responded to the survey had used active learning before the move online. However, 34.9% of the faculty discontinued their use of active learning after the move online, while 43.4% made minor changes and 21.3% made significant changes. Bizot also found that the Computer Science faculty had higher levels of stress after the switch online because of COVID-19.

In October 2020, the Chronicle of Higher Education conducted a survey among faculty members at U.S. institutions to gain insights into how the pandemic affected faculty members from a mental and emotional perspective [

20]. A total of 1122 faculty members responded to the survey from four-year and two-year universities. The analysis of the data highlights that the majority of faculty members experienced elevated levels of frustration, anxiety, and stress as they struggled with increased workloads and a deterioration of work–life balance. This is especially true for female faculty members. The survey also highlights that more than two-thirds of all faculty members were discouraged enough to consider retiring or changing careers and leaving higher education, with tenured faculty members even more likely to retire than others. In addition, tenure-track faculty had some of the highest levels of stress and fatigue. Faculty members faced a multitude of challenges at the same time: abruptly changing their work strategies and habits, learning new technologies, job insecurity due to the economic challenges of higher education, worries about the health and well-being of their families as well as students, and losing collaboration opportunities. The Chronicle of Higher Education’s survey, however, did not explore the experiences of the faculty members from a teaching perspective.

This paper is part of a larger study completed at SJSU which looked at the impact of COVID-19 on students and faculty members [

21,

22,

23,

24]. We surveyed all the faculty members that taught a class in the College of Engineering at SJSU in Spring 2020 (more than a hundred of responses) and interviewed 23 of them. In addition, we surveyed all the students enrolled in the College of Engineering at SJSU in Spring 2020 and interviewed 40 students [

22,

23]. This paper presents a comprehensive description of the results of the survey and of the set of interviews with engineering faculty members at SJSU University after the end of Spring 2020 semester and explores faculty members’ experiences as well as the novel teaching approaches they used in the emergency remote environment.

This paper is organized as follows: there is a description of the research questions in

Section 2, the methodology for the survey is in

Section 3, and the methodology for the faculty interviews is in

Section 4. The results of the survey and interviews are presented in

Section 5 and extensively discussed in

Section 6, followed by a conclusion section (

Section 7). A discussion of the limitations of the approach is presented in

Section 8 and

Section 9 discusses possible future work.

3. Materials and Method: Faculty Survey

The research team based the surveys on the questions that were developed by researchers at Georgetown [

25] and HEDS [

9] to survey the student population, and modified them to be relevant to the faculty participants. In designing our students’ survey, we used questions from the Georgetown survey that related to the students’ personal experiences with life during COVID-19, including questions about the students’ medical situation, living situation, financial situation, and perceptions about the future. We added questions from the HEDS survey about student worries including stress levels, satisfaction with institutional responses to COVID-19, and intent to return. The research team also added questions that investigated student access to resources, student communication with instructors, the availability of faculty for office hours, experiences with controlled testing environments, and specific questions related to laboratories and project-based classes that are relevant to the engineering classes at SJSU. As much as possible, the faculty survey asked similar questions as our student survey. We mirrored the questions for the faculty survey from the Georgetown [

25] survey, which related to personal experiences with life during COVID-19 including questions about the faculty member’s medical situation, living situation, and financial situation. We also mirrored the questions about stress from the HEDS [

9] student survey for the faculty survey. The team submitted an IRB application, and it was approved on 28 May 2020.

The survey design was based upon the Lazarus’ Theory of Stress: “psychological stress is a particular relationship between the person and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and endangering his or her well-being” ([

26] p. 19). This theory is defined as a transactional theory of stress and coping and is related to other constructs in psychology including locus of control [

27] and self-efficacy [

28]. Existing research has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic was stressful to many colleges students and faculty who underwent changes that taxed their resources. According to Lazarus and Folkman, there are two phases in psychological stress: appraisal and coping. An individual in a potentially stressful situation first appraises the situation in relationship to their own sense of well-being: “Primary appraisal is an assessment of what is at stake: “Am I in trouble or being benefited, now or in the future, and in what ways?” If the answer to this question is yes, then people categorize the situation as being a threat, a challenge or a loss.” [

29]. Coping relates to a secondary appraisal of the situation and the individual’s self-confidence to have the resources to deal with the situation. The resources can include physical, social supports, or financial or psychological resources. According to Lazarus and Folkman [

26], coping has two major purposes. First, it regulates the negative emotions that relate to the stressful situation, in this case, the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, individuals can manage the problem by attempting to change the stressful situation. In the COVID-19 pandemic, since the situation was not usually able to be managed by some faculty and students, most of the coping relates to faculty and students attempting to regulate their emotions or distress caused by the pandemic.

Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic was a unique experience for most faculty members students and challenged their regular patterns of coping behaviors. Most faculty and students were not prepared for the lifestyle and education changes initiated by the pandemic and found they lacked the coping strategies to deal with it. “If the individual does not believe he or she has the capacity to respond to the challenge or feels a lack of control, he or she is most likely to turn to an emotion-focused coping response such as wishful thinking (e.g., I wish that I could change what is happening or how I feel), distancing (e.g., I’ll try to forget the whole thing), or emphasizing the positive (e.g., I’ll just look for the silver lining)” [

30].

3.1. Recruitment

The survey was distributed to all lecturers and tenured/tenure-track faculty using the SJSU College of Engineering email distribution list. An email distributed to all faculty teaching in Spring 2020 contained a link to the faculty survey. About one week after the initial email, a reminder was sent to the faculty who have not filled out the survey or have not finished it. A final reminder was sent in week 3. One of the last questions in the survey asked for volunteers to participate in an interview.

3.2. Participants

There were 288 faculty (lecturers, tenure-track and tenured) that taught a class in the College of Engineering at SJSU in Spring 2020. Overall, 98 faculty completed this survey, which represents 34% of the faculty population and equates to a confidence level of 95% with a margin of error of 8%. Because of this low margin of error, the research team is confident that this survey is representative of the faculty teaching in the College in Spring 2020 [

31].

The majority of the respondents who answered the question about rank were lecturers (58); there were fewer tenure-track (18), tenured (13), adjunct (1), and Teaching Associates (1) responding. Of the faculty who identified their gender, 66 were men and 27 were women. It is interesting to note that there were more responses from newer faculty; 45.1% of the faculty responses were from faculty with five or fewer years teaching at SJSU (see

Table 2). Before Spring 2020, only 26 of the 88 respondents had taught a course online. Of the faculty who previously taught online, only seven had taught online for five or more years.

Faculty from every department in the College responded to the survey. The survey respondents were generally representative of the faculty in the College of Engineering with the exception of the faculty in Computer Engineering and Chemical and Materials Engineering who were under-sampled and the faculty in Civil and Environmental Engineering and General Engineering who were over-sampled, as shown in

Table 3.

About half of those who responded to this question (48.9%) did not work outside of SJSU in Spring 2020; however, a significant number, 27 faculty members (31%), worked full-time outside of SJSU in Spring 2020.

6. Discussion

For the discussion, we related the results of our interviews back to the research questions. We will summarize the results in this manner.

Research Question 1: Did faculty experience pressure and stress during the COVID-19 transition to emergency online learning?

Faculty members, in general, had a positive experience teaching in the online environment and defined the transition as easy. For some faculty members, online teaching is convenient. The transition to online teaching was defined by the interviewed faculty members as “smooth”, “seamless”, “pretty easy”, “not that hard”, “not as challenging”, and “convenient”.

Most faculty reported feeling more stress as a result of COVID-19, in particular tenure-track faculty, as described in

Table 6. A large number (31) of faculty members provided comments about their quality of life. As

Figure 2 shows, the most common words mentioned were work, home, and stress. These findings agree with those of other researchers [

13,

14,

15]. For example, Bizot et al. [

19] found that over half of the computer science faculty who responded to the survey had used active learning before the move online. However, 34.9% of the faculty discontinued their use of active learning after the move online, while 43.4% made minor changes and 21.3% made significant changes. Bizot also found that the Computer Science faculty had higher levels of stress after the switch online because of COVID-19.

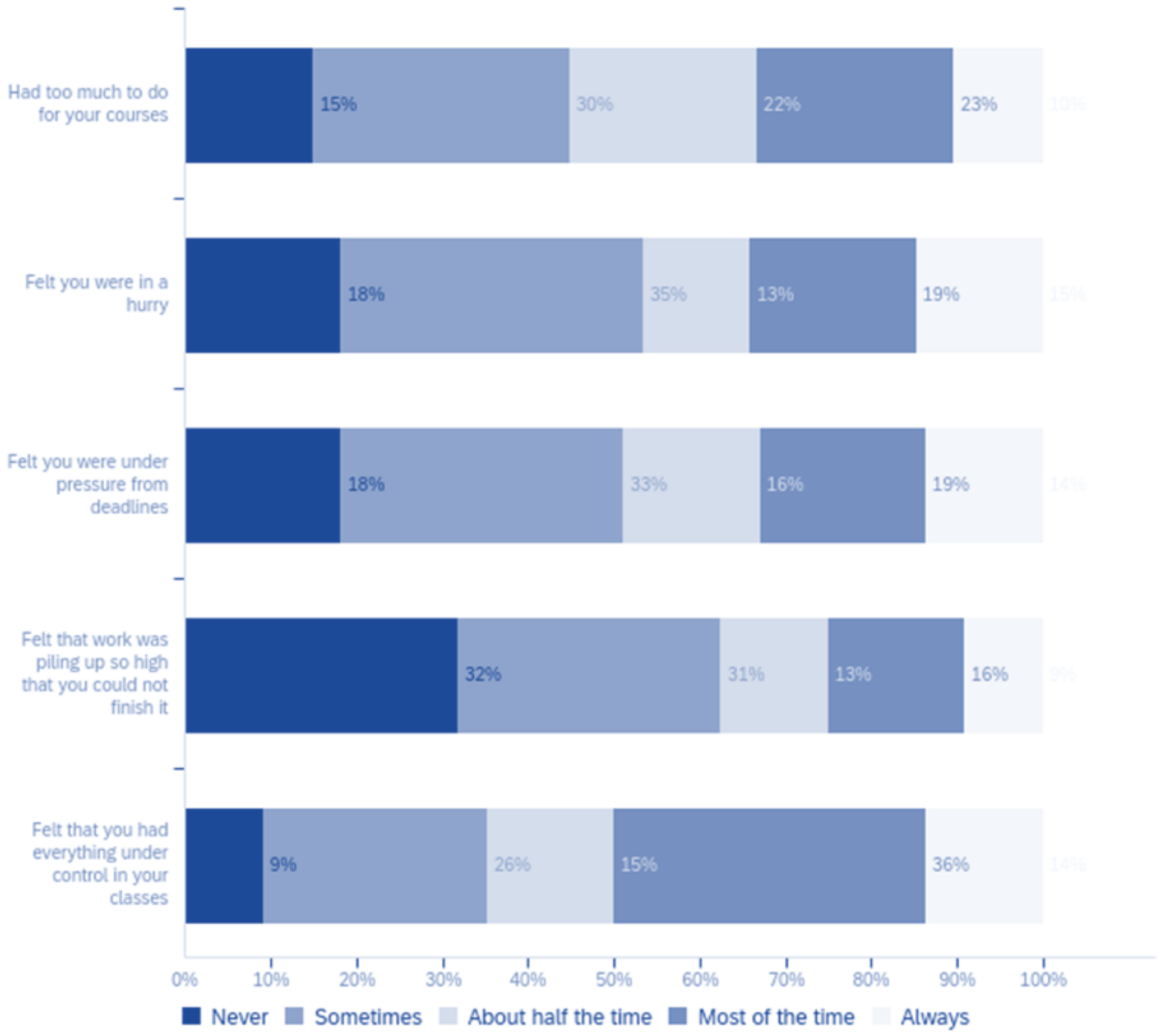

In the Higher Education Data Sharing Consortium (HEDS) survey of faculty [

9], faculty felt overwhelmed in Spring 2020 by the increased amount of work in the newly online classes, with 61% of faculty indicating that they had too many things to do, 55% felt that they were in a hurry, and 51% felt under pressure from deadlines. A second survey, the Chronicle of Higher Education faculty survey [

20], also showed that faculty were experiencing elevated levels of frustration, anxiety, and stress and were struggling with increased workloads and a deterioration of work–life balance. These findings agree with our survey of faculty. However, in our survey, there was a gender difference in stress levels and in the pressures experienced by faculty. Female faculty experienced higher stress levels than male faculty; 73% of female faculty reported a moderate or great deal of stress compared to 63% of male faculty. In addition, fewer male faculty (37.7%) felt they were under pressure from deadlines compared to female faculty (77%), and the female faculty felt they had too much to do in their classes (76%) compared to male faculty (47%).

Research Question 2: What challenges have faculty identified during the online transition and how do they plan to improve instruction?

The Chronicle of Higher Education survey of U.S. faculty [

20] also showed that faculty faced a multitude of challenges at the same time: abruptly changing their work strategies and habits and learning new technologies. Our survey also documented that faculty used new online tools after the switch to a remote learning environment. After the move to online learning, more faculty reported using audio and video conferencing tools (90.6%), webcams (77.3%), online videos or tutorials (68.8%), and YouTube (50%) (See

Table 9).

Most faculty (70.4%) in our survey spent more hours than usual on course preparation after the shelter-in-place. All the female faculty who responded to this survey indicated that they spent more hours than usual on course preparation. In addition, faculty members in Engineering were highly concerned about finding assessments that are meaningful and allow them to assess both lower taxonomy and higher taxonomy skills. The interviewed faculty members changed their assessment strategies, moving from traditional, closed book exams to open books exams, and experimented with different types of assessment strategies such as open-ended exams, multiple choice, or take-home exams. Kyle (see comment above), for example, discussed the need to experiment with different types of online assessment strategies during the semester. This finding agrees with other research on the impact of COVID-19 on assessments which showed that faculty members adopted new strategies to adapt to the remote environment including modifying or dropping assignments and exams and lowering their expectations about the quantity and quality of the work performed by the students [

10,

14].

Most of the faculty members in SJSU engineering have always viewed online teaching with skepticism, and prior to Spring 2020, very few classes in the STEM disciplines were taught fully online. The traditional teaching approach was completely shifted by the COVID-19 pandemic and all engineering classes at SJSU transitioned to online learning in Spring 2020, with limited training and planning for the faculty members. As a result, faculty members experienced an increase in workload at a time in which many also experience an increase in personal needs. Faculty members were also challenged to keep students engaged online and by the organization of hands-on laboratories in a fully online environment.

The survey would have been strengthened if we had asked faculty more details about specific challenges they had during the move to remote learning in Spring 2020. Other studies have shown that faculty challenges with the emergency remote learning include a decreased interaction with students during class time and decreased students’ engagement [

11,

12], increasing concerns about students well-being [

13], and a general feeling that their course quality has decreased [

12]. We did not include questions that asked faculty about these issues specifically in our survey.

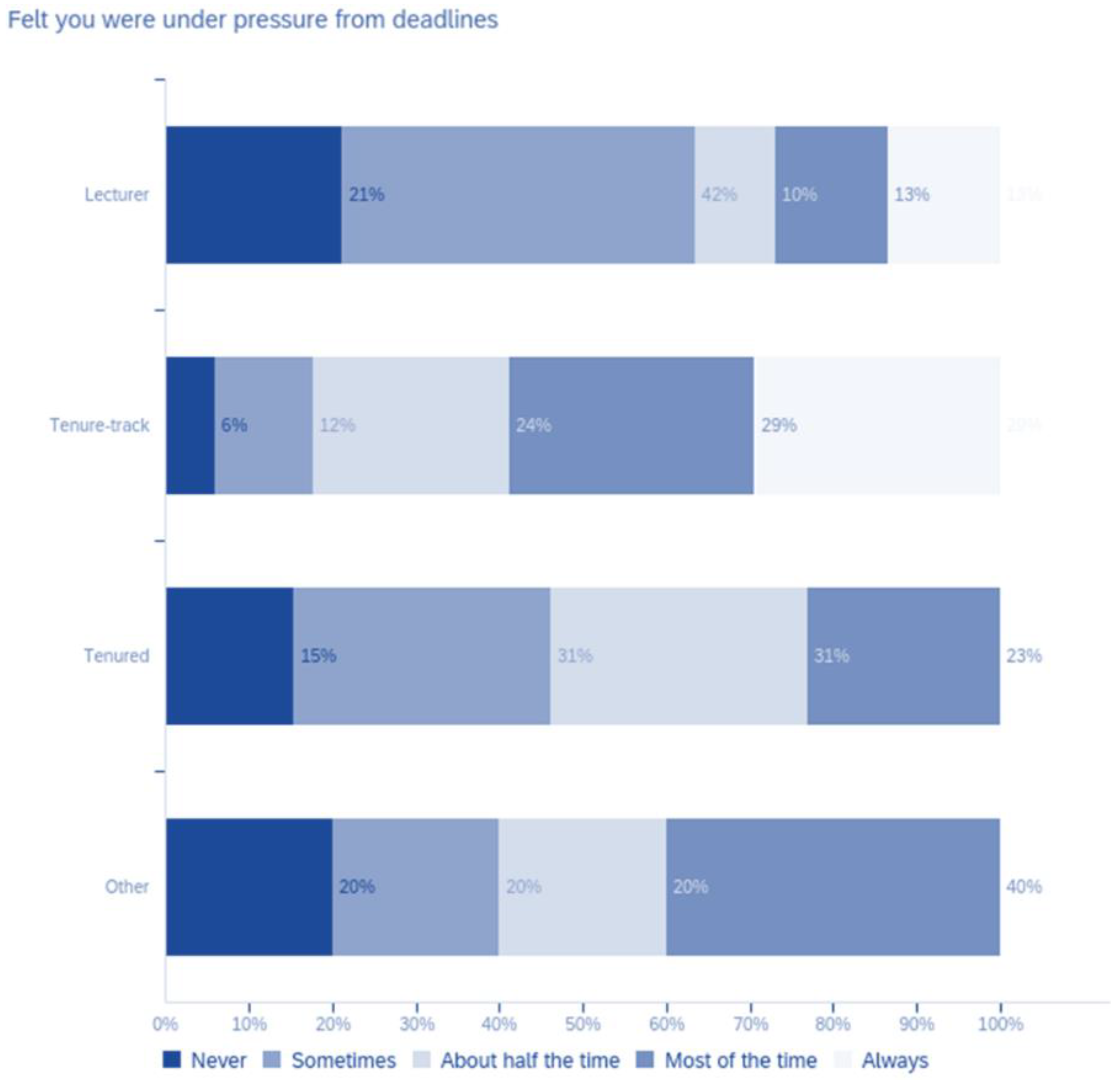

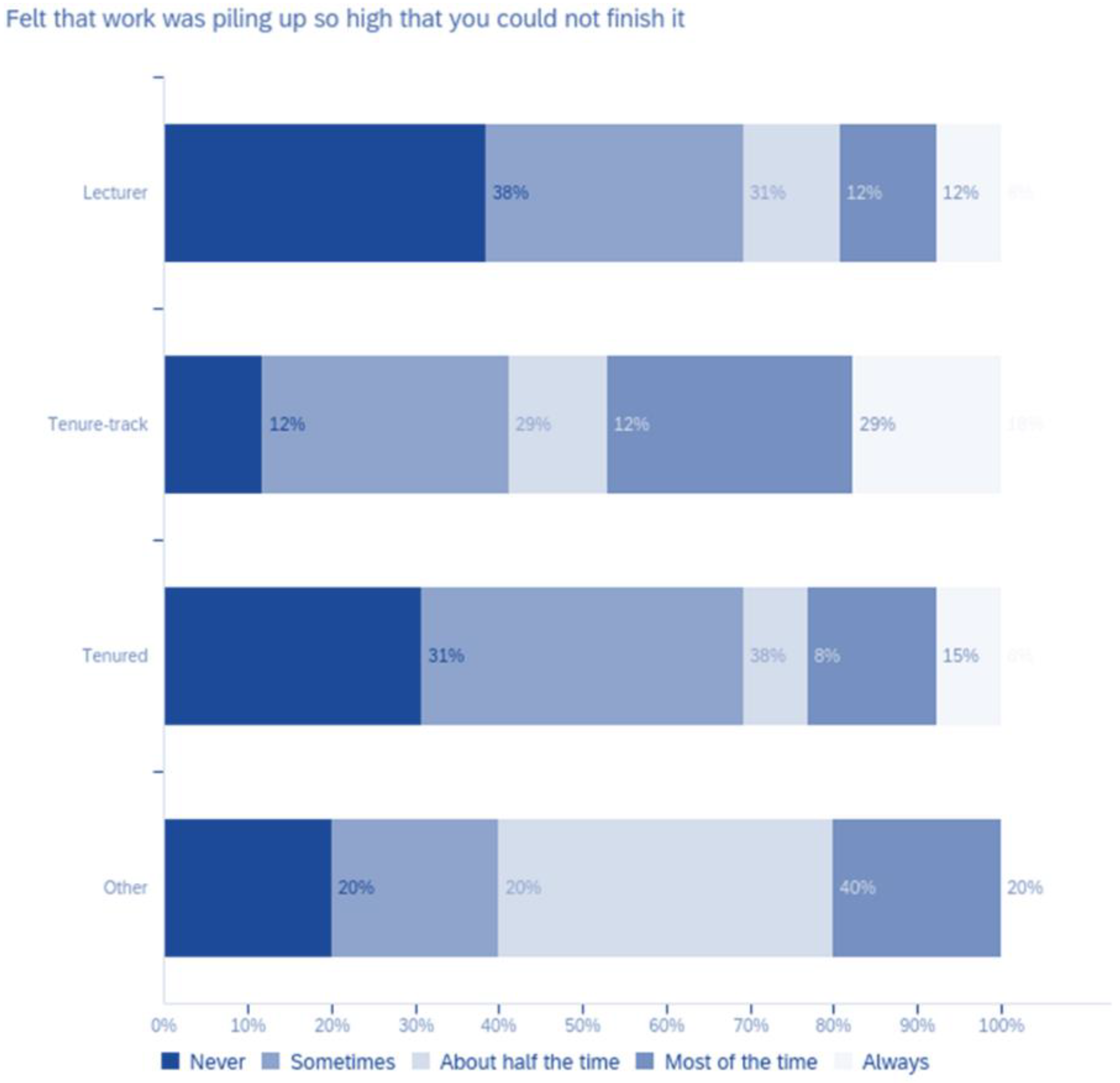

Research Question 3: Is there a difference in the effect of COVID-19 among tenured faculty, tenure-track faculty, and lecturers?

Table 7 and

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show that the perception about the Spring 2020 transition was felt differently by faculty of different ranks. Overall, tenure-track faculty were more likely to report negative feelings than both lecturers and tenured faculty. For example, 33% of all faculty (

Figure 4) felt they had too much to do for their courses all or most of the time, but this percentage increases to 69% for tenure-track faculty and 53% of the tenured faculty (

Figure 5). Moreover, 58% of the tenure-track faculty (

Figure 6) felt they were in a hurry as a result of online instruction, which is in contrast with 34% of all faculty (

Figure 4). Lecturers were the least likely to feel hurried, as 68% reported they never or only sometimes felt this way. Similarly, 33% of all faculty (

Figure 4) felt under pressure from deadlines all or most of the time; this percentage rises to 58% for tenure-track faculty (

Figure 7). Additionally, only 25% of the entire faculty (

Figure 4) felt that work was piling up so high that they could not finish it all or most of the time, but the same answer was given by 47% of tenure-track faculty (

Figure 8). In terms of teaching, 35% of the entire faculty (

Figure 4) felt they were in control of the class only sometimes or never, but this same feeling of loss of control was felt by 65% of tenure-track faculty members (

Figure 9).

Few other studies look at the differences between faculty ranks. The Chronicle of Higher Education survey of U.S. faculty [

20] found that tenure-track faculty had some of the highest levels of stress and fatigue. Our faculty survey agrees with this finding. Tenure-track faculty in our survey experienced higher stress levels than other faculty. In addition, 83% of tenure-track faculty reported a moderate or a great deal of stress compared to 63% of lecturers and 46% of the tenured faculty.

The survey by Tyton Partners, in conjunction with Every Learner Everywhere [

3] included some analysis of the differences among different faculty ranks. The Tyton Partners survey found that child or elder care was a significant challenge for 40% of women faculty members, and tenure-track faculty were more likely to report this concern. In our survey, slightly more lecturers (36%) and tenure-track faculty (38%) had to care for children or elderly people either full-time or part-time than the tenured faculty (30%).

Research Question 4: What are the impressions of faculty members to the learning environments in engineering courses after the switch to emergency remote learning in Spring 2020?

Overall, despite the challenges, at the end of the semester faculty members shared a positive experience in how they were able to transition their classes despite the fact that the majority of the interviewed faculty reported never having taught online before Spring 2020 and were therefore required to transition to the emergency online format with very little preparation and formal training. The general positive experience identified by the engineering faculty members is in clear contrast to the experience described by the students in the transition to online learning, who struggled both from an academic and non-academic perspective [

22,

23]. Most faculty (64.8%) in our survey generally felt that they had everything under control in the remote environment although they also felt that there was too much to do in their classes (55%) and they were under pressure from deadlines in their courses (48.9%). When analyzing these questions by gender, we found some differences; 50% of female faculty felt they had things under control compared to 70% of male faculty.

Our faculty interviews showed that faculty reported that they were faced with challenges in their teaching approach during the transition to emergency online teaching. The faculty reported challenges with grading and assessment, forming a personal connection with the students, listening to and supporting students who were struggling because of their personal situation, maintaining students’ engagement, and “Zoom drain.” In many cases, faculty changed their teaching approach “a whole 180 degree” (Dolly) as they recognize that the emergency online format required different strategies to keep students engaged. Some faculty report decreasing the pace of the class and the quantity of material covered, while other faculty were able to cover a bit more material. The majority of the interviewed faculty taught synchronously with the same schedule as during in-person teaching, used PowerPoint slides to present their lessons, recorded their lectures and made them available to students, and had office hours. A large number of faculty lectured for the entire class time, finding it difficult to incorporate active learning activities to keep students engaged. Both the surveys and the interviews of engineering students point to a large disconnect between the faculty members and students’ experiences in remote learning in Spring 2020 with the students describing their experiences as more negative. Some faculty noted a discrepancy between their experience as a faculty and the students’ experience although one of our faculty interviewees (Arthur) noted that students pointed out to him that their perceptions of the Spring were much different than his. Our faculty interviews also indicated that faculty members generally were unaware of best practices in teaching online including best practices in terms of presentations, grading, and assessment strategies. This aspect is fundamental in an online environment, in which visual clues are eliminated and the student–faculty contact time is diminished.

Research Question 5: What was the impact of the switch online in Spring 2020 to lab classes?

The faculty members interviewed found that moving laboratories to a remote mode was difficult. Specifically, the faculty members found it challenging to provide hardware to the students because of campus closure and safety concerns: Faculty members used different strategies to conduct their laboratory activities, such as using “a simulator” (Larry), and conducting demonstrations (Cristobal). In addition, some faculty members discussed their frustration on the inability to conduct labs in a safe environment (Edouard).

We did not ask any specific questions related to the impact of remote learning on labs in our faculty survey. This, in introspect, would have given us more insight to the experiences of a larger number of faculty than our faculty interviews about the impact of the COVID-19 shelter-in-place on instruction in labs.