2. Informal Education Approaches—A Brief Introduction

Firstly is a brief discussion of informal education pedagogy through the discovery of the academic role becoming that of a ‘duality’ function. The approach to teaching and learning and how this presents itself between academic and student, ‘macro’ and ‘micro’ contexts will be touched upon, highlighting the marketised higher education environment, where power and politics play out.

Considering the concept of informal education as posed by Freire, he notes that “informal education is a dialogical (or conversational) rather than a curricula form…” and that such “dialogue involves respect” [

1]. Such an approach is not just theoretical but has practical application, as and when required. This can also be explored when he argues the notion of the teacher-student roles that can play out both in the established traditional education setting, and other learning domains such as within communities, workplaces and society at large. The ‘duality of roles’ is created rather than the binary traditional definition that can be seen as maintaining hegemonic power. He argues that:

“Through dialogue, the teacher-of-the-students and the students-of-the-teacher cease to exist and a new term emerges: teacher-student with student-teachers. The teacher is no longer merely the-one-who-teaches, but one who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who in turn while being taught also teach. They become jointly responsible for a process in which all grow”.

A similar notion can be suggested for the academic who has been, or still is, a practitioner with relevant practice experience, knowledge and understanding of informal education contexts and settings. A symbiotic role thus emerges as the practitioner becomes the academic or the academic remains a practitioner. The significance of this relates to the key argument being posed that educators create a ‘duality of roles’ within the learning setting, such as the lecture theatre or classroom. This ‘duality of roles’ is where the theoretical concepts and the experienced practice merge in offering validity to the theory and authenticity for the students. Opportunities are created to expand and develop teaching and learning through an array of differing educational practices, such as the use of informal education pedagogy methods and approaches.

If academics consider themselves as practitioners and/or ‘practice the practice’ then this can suggest several possible notions. A synergy of the practitioner and the academic can combine, forming that of a ‘pr-academic’, not a theoretical based and valid definition, but more of an anecdotal observation. The suggestion that those that have practice experience and embed the core values of informal education pedagogy, such as youth work methodology, also embed these within their academic contexts is not one that can be assumed or expected. As the UK has become more and more marketised over the past few decades with the focus upon quantifiable numbers of students completing degrees to maintain the marketisation discourse, the curriculum can be diluted or replaced. Concepts such as ‘reflection, anti-oppressive practice, etc.’ can be topics that are reduced or removed from the curriculum to focus upon other directed themes. The argument posed, as by Ryan, presents a ‘critical activist type approach’ in enabling such informal education pedagogical concepts to remain in the curriculum;

“Pedagogic decisions about reflective activities should be cognizant of the stage of the program/course and should recognise where students have been introduced to reflective practice; how and where it is further developed; and what links can be made between and across the years of the program/course. Choosing reflective tasks with due consideration to levels of professional knowledge and prior experiences with reflection, can enable higher education students to develop these higher order skills across time and space”.

Applying such reflexive activities within the teaching and learning environment from the perspective of being an integrative and important function embeds the concept of reflection itself. As the collection of teaching and learning methods are encountered by the students through a systematic planning approach, these become the ‘norm’ for students as educational practices alongside traditional theory-based knowledge acquisition. Informal education pedagogy can offer students access to explore ‘how’ concepts can be understood and utilised within practice. Reflecting upon their learning as they encounter formative tasks and exercises (case studies, researching and presenting, argument forming, positionality, moral and ethical debates, etc.), individually and in groups, enables the development of their learning before they apply it in practice. Through such activities the theoretical concepts can be discussed and critiqued in the learning space, exploring the meaning, with the ideal of moving from being ‘reflective to reflexive’. Using informal education pedagogy approaches students can develop the meaning of the subject matter, in readiness to expand their deeper knowledge and understanding in discovering other concepts as they draw upon this continual developing learning process.

Within this ‘duality of roles’ there are also instances where core values are able to be maintained that form the personal and professional identity of the individual and thus become the bedrock of the ‘duality’ role they play as an academic. If such conflicts exist within the ‘marketised academy’, the very same skills and abilities the practitioner holds within a practice context can become transferable to the academy. However, the ‘academic’ may or may not see their role or function in such a way, but rather just as the teacher of knowledge. This is posed by Waite et al. explaining that “activism can take place in a variety of settings, including education. Although most educators may not think of themselves as activists, their actions may nevertheless qualify as activism” [

4] (p. 9). These include the ability to be ‘problem-posing and solving’, solution focused, imaginative and creative, empathic and understanding, developing opportunities and possibilities, offering alternative suggestions, facilitating shared dialogue etc. This can be presented within a notion of a continuum whereby the focus is to continue to engage with the prescribed challenges faced, but creating solutions and practices within the constraining framework of the institution. However, it could also be presented as one of the fundamental building blocks of informal education pedagogy, the willingness to challenge and critique where some form of injustice or ‘control and contain’ infrastructure exists. Such approaches are evident more in the ‘macro’ sphere of an institution whereby waves of power exist at varying levels of structural organisational hierarchies. The relevance of the ‘problem-posing’, ‘solution-focused’ concepts and methods as an academic are paramount; as mentioned, the ‘marketised academy’ can become consumed with external drivers that can influence and impact upon the internal organisation of the functions and role of the institution. Where this does happen, such methods can offer firstly an awareness raising function regarding the issues at hand, and secondly methods in considering and presenting possible solutions. If these are utilised and modelled by academics, then they can offer significance to students too within their own learning and, within practice.

To consider the areas where we can explore and try to understand the ‘micro’ contexts whereby such pedagogy may exist, then we move to the space where the teaching itself takes place, the classroom and/or lecture theatre. Such domains can be those where power can exert itself, with the ‘teacher’ or ‘lecturer’ being the one holding the power over the learner or student. This is possible in such an environment where assessment and grading are very much at the behest of the marker with some options open to students to challenge. This power dynamic can be held and maintained both by the potential holder or the receiver of the power. If the hegemonic pedagogy is not challenged in such a way as to unpick and change it, then this will remain. Waite et al. remind us that “if educators and leaders are to advance social justice in schools and communities, they must acknowledge that educational institutions are political entities. The various approaches to politics in education, each in their own way, are useful in this enterprise” [

4] (p. 8). The core values of informal education pedagogy lays this as a key bedrock of practice. This does not necessarily place itself within formalised curriculum-based courses but exists as an addition, usually by the ‘pr-academic’ who creates the space and place for such discoveries to be made, while such themes are collated within the curriculum, understanding and application, usually by how these are interpreted by both the academic and learner, within the ‘classroom’ and practice settings. Such spaces and places exist as Jeffs and Smith [

5] explain, it is often a spontaneous process of helping people to learn. This spontaneous aspect can only take place if such environments are created for the learner to explore such notions, then transfer the learning to practice. This has been identified as being the significant difference between the subject-based curriculum of formal learning and humanistic-based learning which occurs in the process of informal education pedagogy, for example, about identity, about others and our relationships with them, about relationships with the wider world and the contexts of our lives [

6] (p. 2). The theoretical concept of informal education pedagogy can be found within specific degree modules as a continuum from formal educational pedagogy, or applies itself within more generic modules that can have limited coverage. However, within such a hegemonic ‘academy’ whereby specific pedagogies have dominance, the challenges that exist are apparent in how aspects are presented and perceived. As Batsleer [

6] (p. 2) suggests, the notion of empowerment…asking the questions…What is power? How do informal educators engage with power dynamics and conflicts that are relevant? The ‘art of conversation’ is one such notion that exists within the informal education toolkit. This is a key learning tool that encounters many aspects of communication including linguistic, cognitive, purpose, exploration, etc. As is well documented, this works through conversation [

5] and learning through conversation…as the most important method of informal learning [

6] (p. 2). However, conversation also requires a more Socratic approach in discovering learning which is why the notion of dialogue [

6] (p. 2) enables the exploration and enlargement of experience [

5] to develop.

3. Pedagogical Synergies

As Batsleer states;

“most professional informal educators are not described in this way in job descriptions. The term ‘non-formal learning’ is also used in the context of European debates, as are the terms ‘social pedagogue’…”.

This leads to consideration of the possible synergies between informal education pedagogy and social pedagogical theory and practice. Notions of dialogue, accompaniment and situational learning are key factors of informal education, but similar notions exist within social pedagogy. This is supported as Eichsteller and Holthoff [

7] (p. 34) explain: social pedagogy is a social construct, ‘it emerges through dialogue about theory and practice…’ [

8]. The exploration and understanding of ‘Life–space’ is where the space that exists between the professional and the service user (e.g., young person) is one where the life of the young person explores, develops, learns, usually through an everyday activity, a notion that many informal educators can recognise and resonate with and holds significance within social pedagogic contexts, especially within residential care settings.

If we consider that social pedagogy is about enabling holistic learning and well-being through empowering and supportive relationships [

9], these could be aspects that the informal educator could validate as a basis for how they carry out their practice. Relating to the notion of students becoming social justice champions:

“…social pedagogy is concerned with well-being, learning and growth. This is underpinned by humanistic values and principles which view people as active and resourceful agents, highlight the importance of including them into the wider community, and aims to tackle or prevent social problems and inequality…”.

Such focus upon preventing social problems and inequality situates itself well within the value-based theory and practice of informal education pedagogy. This is more so as “within informal education and social pedagogy, the character and integrity of practitioners are seen as central to the processes of working with others” [

11] (p. 3). The synergies mentioned here have significance and relevance within society as the consideration of preventing social problems and inequality can be seen as key subject matter that is explored within HE curricula that are heavily informed by such pedagogies. The purpose here is enabling students to unearth the complexities of such issues alongside theoretical methods and approaches in tackling them.

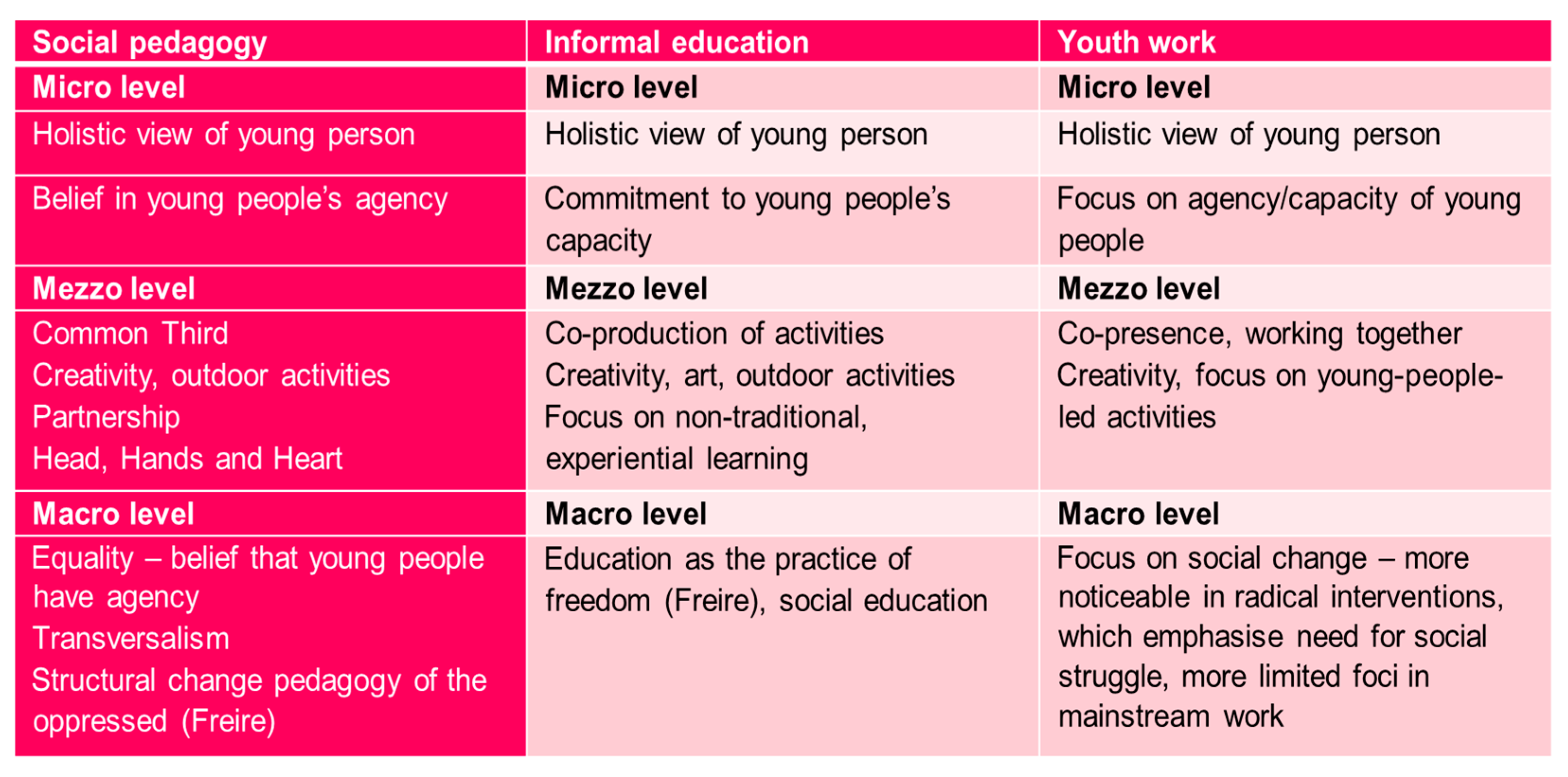

The infographic by Hatton offers an overview across social pedagogy, informal education, and youth work synergies (See

Figure 1).

We can see that across the three levels from ‘micro’, through ‘mezzo’ to ‘macro’ that many similarities and synergies exist. The micro level highlights the common approach of agency and a holistic view of the young person is applied, the application of a shared space and/or activity that enables the learning journey to begin and flourish across the mezzo level. Finally, the overarching macro level considerations are presented as social justice and social change through education pedagogy informed and led by the young people.

This section is focused upon the similarities and synergies argued to exist between social pedagogy and informal education pedagogy, rather than a broader and deeper theoretical based discussion, and thus does not relate to such. The reader may be interested in a deeper exploration of social pedagogic theory that would offer an underpinning knowledge base, including the long historical context and an overview relating to its emerging theoretical concepts; culturally informed variations; and the array of key theoretical thinkers from a range of disciplines, mainly sociology, psychology and philosophy. As Hamalainen states:

“Social pedagogy is not a method, nor even a set of methods. As a discipline it has its own theoretical orientation to the world. An action is not social pedagogical because certain methods are used therein, but because some methods are chosen and used as a consequence of social pedagogical thought…”.

As such the historical theoretical underpinning of the varying influences would be useful to consider how these emerge and transcend across domains of current practice. This is argued by Eichsteller and Holthoff [

7] as social pedagogy is:

“…transcending national boundaries to the extent that inspiring ideas can be influential across different cultures”.

The synergies I would highlight are concepts in social pedagogy such as the ‘diamond model’; ‘head, heart, hands’; ‘the relational universe’; ‘the common third’; the ‘learning zone’; ‘the ‘zone of proximal development’; the ‘3 P’s—professional, personal and private’; and finally, ‘Haltung’. Further explanation, alit in summary form, offers some understanding as to their relevance, significance and relation to informal education pedagogy.

‘Diamond Model’—this is the notion that individuals have many ‘riches’ of knowledge, skills and abilities inherent within them and these can be ‘rough’ to begin with but over time can be smoothed to develop their potential in order to shine. To enable positive experiences through this process, social pedagogy has four core aims closely linked: well-being and happiness, holistic learning, relationships and empowerment [

13]. Such experiences are argued to be fundamental and Eichsteller and Holthoff [

14] suggest that positive experiences become an important vehicle in meeting the four core aims [

8] (p. 49). This concept relates to the academy learning environment as the students begin their academic journey as ‘rough diamonds’, having existing knowledge, understanding and skills that they bring with them as valuable capital to draw upon. Through the learning journey, students can smooth their sometimes more strategic understanding to become much more detailed and deeper thinkers. Using a holistic approach to students’ learning the academic can harness their development in such a way as to enable them to develop academically but also personally and professionally. It is argued that if students are happy and have a healthy well-being then they can engage with academic learning more effectively. Drawing upon a range of differing teaching and learning methods also presents a holistic approach whereby the students’ learning styles, even though this concept is contested, can be adhered to across the student cohort. Holistic learning, though, can go further as the adoption of the importance of relationships and empowerment of students is applied, then their potential to become ‘shining diamonds’ is in reach.

‘Head, Heart, Hands’—this concept considers the three domains of a person who draws upon social pedagogic theory to inform their practice. The ‘head’ engages in reflection to consider the concepts and theory being used and refers to the knowledge we have and our ability to connect this to the information we are given [

8]. The ‘heart’ is where the emotional domain is encountered and offers the opportunity to use one’s personality and positive attitude to build relationships. This is sometimes a controversial aspect of professional discourse, but in social pedagogy is inherent, as the notion of love is considered as a means of conveying the passion for incorporating human rights and social justice [

8] (p. 36). The ‘hands’ are the vehicle by which engagement and interaction between people is enacted via a mutually beneficial activity. This activity can be varied according to the interests, relevance and purpose of the interaction. Even though this was suggested to be a concept that can be applied within the practice context, it can also be argued that it can be applied within the ‘academy’. If the logic of this concept is applied to the classroom setting, then it can be considered in such a way as to aid the learning process itself. The ‘head’ brings cognitive functions to the fore in drawing upon the notion of reflection to support the uncovering of the complexities of theories within the subject matter and consider how these relate. Engaging with reflection from the ‘head’ domain offers opportunities for thinking to take place before any future action is considered and applied, a very relevant method in relation to working with people. The ‘hands’ enable the academic to draw upon a range of differing activities that are relevant for the specific subject matter to be explored. These can vary and can include, but are not exhaustive to, activities such as icebreaker games; role-play scenarios; case study deliberation; creative and arts-based activities; visual and audio based activities, etc.

‘Relational Universe’—this is where the ‘agency and emancipatory’ practice of individuals is fundamental. The relevance of those around the individual is the most important aspect as they determine the significance of each person. The universe around them includes spinning relationships, like planets that are constantly moving, and thus such relationships may change over time. This is where the significance of those around them can change. As Thempra explains:

“In practice, it is therefore important for the child to define their relational universe, supported in this by carers and others as the child explores who they feel is able to support them now or in the future”.

However, we must remember that from the moment we are born, we are connected to various individuals [

8] (p. 46). Some of these are thrust into an individual’s relational universe, but hopefully over time these can be chosen and applied significance or importance to by the individual. Within the ‘academy’ context the ‘relational universe’ for students will also vary, influenced and/or impacted upon by the social and cultural capital that students bring with them. This can be a very useful resource for many students as many will be exploring a whole new place, environment, expectations, independence, and responsibilities for the first time. From this the ‘relational universe’ will be wide reaching, complex, with new relationship building, re-alignment of those they rely upon, developing new ‘persons of importance’, etc. For others this will be limited, simplistic, relationship-building but not by choice, relying upon ‘persons of importance’ too much, or not enough. Students’ ‘relational universe’ will also be informed and influenced by their particular ‘needs and wants’ as they travel through their new learning journey. This self-defining moment for many is a valued and fundamental building block for developing as a person, whereas for others it can be a very challenging and difficult period. However, as this journey unfolds the ‘persons of importance’ will change according to the context of the present situation, whether it is not a choice, such as which academic teaches the students, or is a choice, where the student can choose who to speak to regarding an issue of concern. For the academic this is of importance as awareness of this can enable the students to grow, thrive and flourish, as well as creating a circle of support if needed.

‘Common Third’—This requires the intervention of an activity between individuals as a way to support relationship building and thus strengthen the relationship [

8,

16]. The shared situation of the activity taking place is the focus of the learning, with an equal status placed upon each individual, rather than the relationship itself. Exploring this shared situation of equal status within the ‘academy’ can be somewhat difficult where organisations inherently have systems, and sometimes (but not always) cultures are contrary to this approach. However, such shared situations can be found within the classroom environment, with the academic enabling these educational practices, again, applying the concept of equal status, even though it could be argued that this will not be fully reached. Using activities that explore, critically analyse and consider methods and approaches to aspire to equal status is where student learning can be developed to enable application in practice. As with the ’hands’ domain mentioned above, the activity is the mutual method by which the process takes place and is where the individuals concerned, in the academy, both students and academics, experience the shared situation.

‘Learning Zone’—This approach requires the need to go through a particular learning process in order to further achieve. As Gardner [

8] explains, growth and development can only take place in the ‘learning zone’, but to arrive at this zone the individual must reflect and establish their current starting point. This starting point is identified as the ‘comfort zone’ where [

17] things are familiar to us, we feel comfortable, and we don’t take any risks. However, if we move too far too quickly then the ‘panic zone’ is entered where developments can be hindered, with risks not being manageable. The ‘learning zone’ is where carefully managed risk is situated but sufficient support needs to be available to enable the learning to take place. For many students, the ‘comfort zone’ or the ‘panic zone’ can be the places they tend to fall within, foregoing the ‘learning zone’ altogether. This can be presented as students maintaining a safe space and position in not exploring new knowledge, concepts, skills, etc., with the repeating of subjects in their learning. The opposite is where sometimes students jump from a safe space to the area where major issues of concern and problems begin to occur as they fall into their own ‘panic zone’. This can present itself as students struggling with engagement, missing deadlines, lower grades, reduced attendance. This is where such teaching and learning pedagogies carefully support students to keep, as much as possible, between the ‘comfort zone’ and ‘panic zone’ and within the ‘learning zone’ where new knowledge, understanding and skills can be explored and potentially mastered. This will need careful consideration to maintain an approach of both ‘challenge’ and ‘support’ for students to further develop, while ensuring that they don’t become fearful or anxious about their learning. The process can be one of ‘constant flux’ as students fluctuate ‘back-and-forth’ between the zones as they manage the complexity of the varied subject matter they are exploring.

‘Zone of Proximal Development’—This concept [

8,

18] was created by Russian psychologist Vygotsky who defined this as;

“…the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers’…”.

The ability to explore a process together with the intervention of another to share potential abilities can offer consideration of increased options, rather than exploring individually. This reflects and draws upon the notion of learning from others as well as oneself. This concept sits well within the ‘academy’ as there are inherent systematic processes that enable and support this to take place. These can include the various assessment types (diagnostic, formative, summative) and development methods (feedback, feed-forward, grading, threshold concepts). Such systems can aid focus on where the actual development has taken place and where potential development could lie. This could enable higher grades, deeper and wider content exploration, and improved critical analytical arguments. However, the ability to draw upon such systems is one that relies upon engagement to enable potential to be explored and possibly reached. If ‘problem-solving’ techniques are explored and understood within the teaching material, then these can be drawn upon in supporting the above processes.

‘3-P’s: Professional, Personal, Private’—these are suggested to be intertwined with each other as the practitioner encounters relationships and intervention with others, while recognising ‘how’ they impact upon this. As Charfe and Gardner [

8] explain, the 3-P’s offer a reflexive framework which allows practitioners to understand and manage these three aspects of self. The ‘professional’ explores the purpose of the role and is fundamental [

20] to the relationship. The ‘personal’ draws upon the exploration of who one is [

20] in enabling the relationship to become more genuine. The ‘personal’ also enables the opportunity to share attributes that can foster connectivity between individuals. The ‘private’ [

20] sets the personal boundaries of what we do not want to share and is not brought into the relationship. The ‘3-P’s’ become a ‘moral compass’ [

8] as they enable navigation through the process in keeping these in check. Such a concept within the ‘academy’ may hold more relevance to many as they explore the role that they play as academic, educator, and person of knowledge. Some academics would revert to the ‘teacher-pupil’ perspective where the boundaries and lines are clearly demarcated and never overlap. The personal and private are never dawn upon within the professional domain of the relationship, with a particular status of authority being applied. However, considering another perspective, students in HE are adults (over 18 years old in the UK) and the same approach may not succinctly fit this context. If such roles are not explicitly demarcated as both ‘learner and educator’ as adults, with the expectation that ‘social-norms’ apply in how they are to be treated, regarded, related to, etc. then this can cause a ‘fuzzing’ of the three domains. However, from a pedagogic perspective this would be welcomed, albeit carefully applied and led by the individual and organisational policies and procedures. For the academic to share some very carefully chosen and relevant personal aspects of their lives with students for the purpose of developing learning can be useful, offering authenticity to the learning. This does not compel either student and/or academic to do so and should be a carefully considered choice. For example, if the subject matter is exploring the ‘education system and its impact upon young people’s development’, then an academic sharing some personal experiences of how their education journey impacted upon them could offer some connection to the students in considering their own educational experiences, and more importantly that of others.

‘Haltung’—This concept could arguably be considered as the core element of social pedagogy and can resonate extremely well with informal education pedagogy, as it is derived from within the person and how they think, see the world around them and those within it. ‘Haltung’ is a German word or term which roughly translates as ethos, mindset or attitude [

7,

8,

21]. This is where beliefs and values [

8] (p. 35) shape us as individuals and is based upon our values, philosophy, morality and concept of the world [

7]. For the academic, this concept can be one that can either be the ‘guiding light’ as they navigate through the ‘academy’, or a constant challenge as they wrangle with conflicting issues and demands and with their own values and beliefs. Within the pandemic, this has been ‘played out’ as it impacted upon the HE sector with an array of issues for students including morale and well-being, general health, motivation and engagement, attainment and attendance, limited ability to travel and meet others, anxiety and worry, changing approaches to teaching and learning from initial expectations. Whilst students were affected in differing ways, it impacted upon all. The ‘Haltung’ that was applied across the sector varied as many HE institutions took an approach so as to enable a connectiveness to be continued through a number of initiatives; adapting assessments, applying reasonable adjustment to deadlines, increasing the remit of ‘exceptional circumstances’, working with professional and regulatory standards bodies for many ‘applied courses’ for guidance to apply reasonable adjustment to the standard requirements, offering increased pastoral support, re-alignment of learning and IT resources to meet changing needs, additional support with accommodation, offering food parcels, etc. For some academics this would resonate with how practice settings responded to the pandemic, as many did, with many academics applying similar approaches with their student cohorts. To align this with the classroom setting, ‘Haltung’ can sit well within the subject matter of many ‘applied courses’, working with people as the bedrock of exploration before other concepts are covered, thus setting the foundation for how and why the subjects covered are relevant. More importantly the approach taken is to understand these concepts and their purpose for both knowledge acquisition and their understanding of how to apply in practice.

To summarise these concepts, social pedagogy encompasses a range of aspects including being child/person-centred; has a strong focus upon relationships, increasing engagement and agency; and draws upon the rights of the individual in challenging social problems and social injustice. This is underpinned in seeing the individual in a holistic way regarding both education and well-being. The various concepts discussed above, individually explored with significant examples, have links and connections to each other and are not necessarily suggested to be used separately. The ‘head, heart, hands’ and the ‘common third’ concepts have overlapping aspects with the use of ‘activity’ in the shared learning experience. Others have ethical and value-based aspects that overlap: ‘Haltung’ and the ‘3-P’s: Professional, Personal, Private’, with the ‘Zone of Proximal Development’ and the ‘Learning Zone’ lending themselves more to an understanding of exploring what is possible to further develop, while carefully challenging oneself. While these concepts are not mutually exclusive, and many others can be considered in relation to learning in the ‘academy’, it is argued that they are an inter-linked tautology and can be utilised as such. These can form a part of the academics’ educational practice in developing a teaching and learning strategy that becomes a framework or scaffolding to hold the various subject matter together. This can have significance, enabling students to feel that they can ‘hold on to’ and manage their own learning.

Finally, as Storro [

22] (p. 70) reminds us…“it is everyday life that a social pedagogue carries out much of [their] work…in…ordinary everyday situations.” The notion that such practice takes place in the ‘everyday’ is also where informal education pedagogy takes place, suggesting that such pedagogies are in synergy. Considering the notions of dialogue, accompaniment and situational learning along with ‘Life-Space’, it could be suggested that these have many aspects in common with each other.

4. Pedagogical Impact

To explore and understand where such examples of pedagogical impact exist and what they present themselves as, we need to consider the many actions, direct and in-direct, that academics or ‘pr-academics’ carry out. These are usually supported with a core rationale and/or purpose for carrying out such types of practice within the classroom environment. Some education pedagogies suggest that these teaching practice examples are not necessarily possible to be drawn upon in lecture theatre environments due to the practical and logistical arrangements of tiered seating and tables. However, this is contested as informal education pedagogy can take place in any setting and context. The exploration of how learning is connected is a key factor as Bridgstock et al. put forward: “much learning is inherently social, and the roles that social relationships and networks play in professional and lifelong learning are of great relevance to universities that wish to strengthen the employability of their graduates (Field, 2009)” [

23] (p. 6). Examples of this could be using the ‘art of conversation’ and ‘dialogue’ so that students discuss and debate a relevant issue with peers besides, above and below them. Practice activity could lend itself to the explanation of informal education approaches as students are able to explore and develop new learning experiences while in such a confined space, hence situational learning [

24] taking place. Others are the planned tasks and formative exercises placed within the formal teaching schedule that offer students the opportunity to experience such practice, exploring topics of interest in such a way as to pose the problem to the students in applying the task of solving the issue posed. This then creates and enables the space, as Freire suggested, for ‘problem-posing’ learning activity to take place [

1]. Such a space can generate an almost organic unfolding of social interaction, problem solving, conversation and dialogue, understanding, knowledge, experiences, and group work through the shared learning experience. However, it is not just the tacit activity in which informal education pedagogy takes place, but also in the continuous social interaction between academic and student or ‘teacher’ and ‘learner’. As Bovill argues;

“You need positive relationships between teacher and students, and between students and their peers, in order to establish the trust necessary for co-creating learning and teaching. And through co-creating learning and teaching—involving shared decision-making, shared responsibility and negotiation of learning and teaching—teachers and students, and students and their peers, form deep, meaningful relationships…”.

The focus of relationship building is one of the key concepts and methods that informal education pedagogy draws upon in establishing a meaningful learning environment. This becomes the ‘vehicle’ for the individual and shared learning journey to flourish. The notion of who is the teacher and who is the learner in this duality of relationships is not in question, but does offer some reflection upon the consideration of how the learning takes place. This is also underpinned with the concept of reflection, as the learning experience, even within the classroom setting, becomes one that enables the exploration of reflection in considering the above problem-posing issues. Teaching in such a way offers experiential learning within a ‘safe space’ for students to practice their developing skills set in readiness for the practice context. As Brookfield re-affirms; “teaching in a critically reflective key is teaching that keeps us awake and alert. It is mindful teaching practiced with the awareness that things are rarely what they seem” [

26] (p. 22). The theoretical concepts that underpin the pedagogy can be drawn upon by the professional (academic) in how these are utilised and delivered. This, however, is where the teacher then needs to provide a ‘modelling’ of the concepts for students to model themselves with their peers, through group work exercises and other formative tasks assigned within the classroom setting. This presents the transparency of shared learning in that “showing students how we apply critical reflection to our own teaching and naming for them that this is what we’re doing, also helps us earn the moral right to ask them to engage in the same process” [

26] (p. 21). The showing of engagement by the teacher can enable students to engage in the learning process. This approach is one that informal education pedagogy draws upon when working within the practice context. The ability and openness of the practitioner to engage in the learning journey together enables and develops a stronger relationship between them and those they are supporting. This can present an authentication of shared learning, as Freire noted;

“The teacher’s thinking is authenticated only by the authenticity of the students’ thinking. The teacher cannot think for her students, nor can she impose her thought on them. Authentic thinking, thinking that is concerned about reality, does not take place in ivory tower isolation, but only in communication”.

A further key concept of informal pedagogy is that of drawing upon a ‘toolkit’ of skills that enable engagement to take place using ‘activity’. This draws together individuals through the shared experience of the activity itself. Within the teaching context, utilising such methods and approaches can offer a wider accessibility for students with varying learning needs. As Brookfield re-affirms in relation to using a varied teaching approach: “if skillful teachers create classrooms that connect to what we know about how students learn, then we need to work intentionally to integrate imagination, play, and creativity into our teaching” [

26] (p. 126). This varied approach is where the practitioner can adapt and apply the ‘toolkit’ of methods in relating to and engaging with others across many contexts and environments. Again, such approaches bring together the concepts of problem-posing, creativity and reflection through Freires’ praxis cycle when he states: “problem-posing education bases itself on creativity and stimulates true reflection and action upon reality, thereby responding to the vocation of persons as beings who are authentic only when engaged in inquiry and creative transformation” [

2] (p. 57).

This can encounter the academic’s personal value base that informs their professional values and principles when presenting themselves to their students. This too has links with Freires’ praxis concept as “…praxis–action that is informed (and linked to certain values). Dialogue wasn’t just about deepening understanding—but was part of making a difference in the world” [

1]. Through this process a cycle can occur of reflection, action, development of theory and thus development of new knowledge. This new knowledge can be further developed as the cycle is constantly drawn upon. This is further supported through the work of Ford and Profetto-McGrath who drew upon the praxis concepts as informed by Freire, Habermas and Grundy [

27]. They argued that “praxis is a form of action and reflection; action that is informed by reflection, and reflection that is informed by action” [

27] (p. 342). Examples of this can be the various types of support and guidance offered including the caring for others’ well-being. As well as the usually timetabled student tutorials that take place, whether individual, group or peer, many academics go beyond this forging space and time to offer more support as needed. This additional time and space could be just the moment that the student is in a metaphorical place of self-fulfillment, achievement, or safety/well-being. Other aspects are also important to consider as the approach used by the academic with the student can be the fundamental trigger for acceptance or refusal of any support or guidance. As Jeffs and Smith [

1] explain:

“In these settings there are specialist workers/educators whose job it is to encourage people to think about experiences and situations. Like friends or parents, they may respond to what is going on but, as professionals, these workers are able to bring special insights and ways of working”.

This ability to respond in such a way is also supported by Bridgstock et al. “Valuable learning is achieved through situated practice that is embedded into the framework of social support and development” [

23] (p. 6). This also reinforces the ‘modelling’ approach for students in the hope that they can also re-enact this within the practice context.

5. The Pandemic and the Potential Impact within Society

Since the unfolding of the pandemic, society as a whole has changed insurmountably as it has affected the general population so significantly that the infrastructure has been under major pressure to maintain its current state. The impact has been both personal and professional for so many, as has been seen in the public admiration for those working in the National Health Service, social care and those deemed as key workers. Informal educators such as youth workers were eventually given key worker status along with the array of support that was offered to many young people and families in need within many communities across the UK. In contrast, the devastation it has inflicted upon many families of loved ones lost, and many still living with the aftereffects of COVID-19, has been evident. The professional impact has also created an environment of possible change in how the workplace is perceived, with the previously argued need to work ‘on-site’ or ‘in the office’ no longer relevant, as was shown when many had to work from home, and still do. For informal educators this in itself presented many challenges, but an array of creative methods and approaches were used to continue to meet needs. These ranged from continuing 1:1 support work via online platforms or telephone, home visits with carefully ‘socially distanced’ rules applied, and adapting the usual programmes of work to respond to the local needs of communities, such as delivering food parcels and offering outside leisure activities. Where informal education pedagogy came to the fore was in how the population came to adapt to the situation in learning new modes of everyday life activity such as using technology to link with family, friends, and colleagues. The emergence of new knowledge, understanding and skills development has shown that learning can take place when not expected, as again “it is often] a spontaneous process of helping people to learn” [

1]. The exploration of the ‘personal’ has also been highlighted within society as the means to ‘stop’ or ‘slow down’ has created space for personal connections to be reviewed or re-established, and even for the forging of new ones. These created spaces can be suggested to be where learning has taken place in a unique situation through a variety of methods seldom drawn upon, such as more virtual platforms, increased interaction with those not usually in contact, and even a conscious effort to connect with those not normally or frequently connected with. This could present the suggestion of situational learning that Lave and Wenger [

24] explain as social relationships forming through a process of co-participation where informal education pedagogic learning is seen to be a process of social participation, even if using differing methods or approaches and in differing contexts and settings. Such learning can be deemed to occur through the everyday situations of the action’s individuals take via the social process of thinking, perceiving, problem solving and interacting in forming such relationships. These everyday situations can be described as individual narratives or life narratives as Goodson et al. suggest: “the stories we tell about our lives and ourselves can play an important role in the ways in which we can learn from our lives” [

28] (p. 2). As the pandemic has presented an array of life changing narratives, both positive and negative, such stories have been fundamentally impacted upon by the pandemic in ways that could not have been imagined. However, there has also been a differing approach to learning both in the ‘academy’ and society at large. With the increase in virtual learning, teaching from home, developing new skills, social structures (e.g., families) being in the same place for longer periods of time, and the emerging support for a range of public services and for neighbours, new learning can take place: “such learning, in turn, can be important for the ways in which we live our lives. But the relationship between life, self, story and learning is a complicated one” [

28] (p. 2). Such learning has also offered the opportunity for shared learning experiences, both through choice and being forced to change as circumstances change.

To offer relevance to informal education pedagogy within the pandemic environment and situation, a possible ‘community of practice’ can be considered to have been formed. The population shares the same pandemic environment which could be suggested to be where practice emerges at being one community (within the pandemic bubble). As [

29] explained, learning is formed from a combination of community, identity, meaning and practice. The community creates belonging from the physical and social disconnection the pandemic has created; while the new or developing individual and their identity become more than before, in that the experience that takes place creates a new meaning of the different social world surrounding oneself, and the notion that learning is formed through the ‘doing of activity’ that forms developed practice [

29] (p. 220). Even though the social world around us has changed, the ability still to be involved is still present, but in different forms and contexts, as we are all involved in communities of practice all the time; at work, at school, in family life [

29].

Such new spaces and places of learning that have emerged within situations forming ‘communities of practice’ may also need a more emotional state of mind to carry them through to whatever a post-pandemic environment, if there is to be one, will look like. Through this dialogue, Burbules [

30] alludes to the human feeling of hope that is central to our achievements through learning, as often it is not clear what we will gain or learn, but faith in the inherent value of education carries us forward. If so, then we can flourish in the changing world, via the informal education pedagogy that has presented itself to us. This, it could be argued that this is needed more so now in the current context of the pandemic as well as due to other socio-economic factors (austerity cuts, marketisation of education, marginalisation of particular demographic groups) which have impacted upon society, and which will be discussed further in the following section.

6. Transcendence of Pedagogy

The final section argues that such pedagogy transcends into the wider society in how students become ‘social justice champions’, personally, professionally, and societally (value-based theory into practice). It explores the notion that student practice in the field is influenced by the pedagogical style they have experienced within their learning.

There is an array of literature relating to this notion across a selection of differing disciplines and disciplinary professional fields, investigating the possible link between learning experience and field practice. Many present the case that existing teaching and learning tends to be highly theoretically based, with only some having opportunities to explore links with practice, but an expectation that the student has the inherent ability to make these links. A selection of research literature across disciplines such as nursing, teacher education and some arts based subjects seemed to adopt this theoretical, expected approach, whereas other disciplines such as social work and some medical areas tend to relate to the importance of the learning experience for practice. However, there are mixed opinions regarding nursing degree learning, with some adopting this approach while others lack focus upon practice and experiential learning, especially relating to leadership practice. Some of the previously discussed methods and approaches drawing from an informal education pedagogic perspective, such as observation, feedback and modelling forming a ‘community of practice’, can be drawn upon from the researched literature. Additional methods explored include using ‘simulation-based learning’, ‘interpretative pedagogy’ and ‘problem-based learning’. When exploring students’ ability to master the art of conducting, Postema (2015) noted that students struggled to link the approach of ‘professional artistic direction’ with a shift of approach to ‘educational conducting’ [

31]. He argued that:

“Students through observation and feedback have the opportunity to create their own ideas about what is appropriate or inappropriate behaviour when conducting an orchestra. Observation and modelling also provided possibilities for students to develop and evaluate their self-efficacy and self-reactiveness”.

Observation and feedback are key attributes within an informal education pedagogical approach to education practice, both within the classroom setting and within the practice context. Students’ practice experience is monitored by supervisors in the field offering feedback as they progress, hopefully achieving a standard that will enable them to become independent practitioners themselves. Within the learning environment academics can draw upon observation within formative tasks and activities and the use of visual assessments such as presentations, offering verbal feedback accordingly. This can also include the method of ‘modelling’ whereby the student re-enacts the approaches of others both in practice and in the classroom. Postema (2015) noted that learning together in groups and/or with peers was also seen as a useful method;

“The theory of ‘communities of practice’ suggested learning itself, is an improvised practice and apprentices learn mostly by their relationship and participation with other apprentices and expert others”.

This can also be echoed when students work with their peers on tasks and group assessments, as well as learning from others in practice. A repository of experience can be stored and built upon as students develop and master new knowledge, understanding and skills. This importance of experience was identified as Jones and Vesilind (1996) explored reasons as to why student teachers became more reliant upon experience than was expected, throughout their training period and assessment. It was noticed that “pre-service teacher education programs traditionally offer students courses in theory and methods and then require student teachers to implement these during student teaching” [

32] (p. 111) with the expectation that they can apply them accordingly. Their research found that this was the area where such expectations changed to drawing upon a differing method, that of experience. This was alluded to as follows: “the picture of student teaching that emerges from this study is of several processes by which student teachers used experience to reconstruct prior beliefs and definitions” [

32] (p. 111), whereby the student brings with them some prior resource that they can draw upon, but with the requirement of further experience to build upon this resource. The findings were profound as they highlighted in their conclusions: “this study suggests that student teaching experiences do more than simply confirm or elaborate the pedagogical knowledge held by student teachers prior to teaching” [

32] (p. 111), thus highlighting the importance of experiential learning. Within disciplines and professional fields where experiential learning, a key informal education pedagogic method, is part of the learning process, this can support the arguments posed by Jones and Vesilind (1996).

Other methods and approaches within the literature, ‘simulation-based learning’, ‘interpretative pedagogy’ and ‘problem-based learning’, appear to have an affinity with that of informal education pedagogical education practice as key skills that would support students learning from the classroom setting to the practice context. As discussed earlier, ‘problem-posing’ techniques from a Freirean perspective were highlighted as an approach that could explore issues using criticality to analyse the details, to be ready for what could emerge in the future. This relates to the research by Kwan (2008) when exploring the adaption of teaching and learning approaches to ‘problem-based learning’ types within teaching education programs. After analysing the data, she found that;

“It appears that the problem-based scenario inductive inquiry workshop mode of delivery, which offers hands-on experience of a variety of teaching approaches, deserves greater attention and has higher preference in the teacher education programme by addressing both conceptual mastery and pragmatic practice”.

The suggested link of particular methods and approaches used, mentioned in the literature, re-affirms that informal education pedagogical approaches offer the link between theory and practice though experience via the use of a collection of methods such as ‘problem-based learning’. Such learning has been claimed to be able to transcend into practice from the classroom as “problem-based learning can also help to strengthen a positive professional attitude by pursuing the ideal of life-long, self-directed and group-based collaborative learning” [

33] (pp. 340–341).

As identified from the literature, ‘simulation-based learning’ and ‘interpretative pedagogy’ was discovered to support the contextualization of learning in McPherson and MacDonald’s (2017) research into how effective leadership practice is needed for qualifying nurses as they venture into their practice settings. They argue that “interpretative pedagogy speaks to a fundamental transformation in the nature of education—moving from the epistemological to the ontological (Doane & Brown, 2011). This shifts a nurse educator’s view of the relationships between teachers and learners, the way learners interact with the material, and how this is connected with clinical practice (McGibbon & McPherson, 2006)” [

34] (p. 50). They noticed that particular types of teaching and learning practice impacted upon trainee nurse’s ability to contextualise the theory as;

“…traditional lectures where learners assume a passive information-receiving role continue to be the mainstay for many nursing programs (Applin, Williams, Day, & Buro, 2011). This passive learning undermines critical thinking skill development and active engagement with the concepts. Active learning strategies have been shown to contextualize learning and to overcome many barriers in nursing education, such as content overload, classroom time constraints, and large student numbers (Hudson, 2014)”.

This highlights the Freirean concept of ‘banking’ teaching where the recipient is the vessel of depositing knowledge and becomes passive in the process. The ‘active learning strategies’ McPherson and MacDonald refer to include methods whereby the student becomes engaged in the learning process as an active part. Referring to such approaches and methods, “in interpretative pedagogy, the focus of study for both student and teacher becomes that of enhancing and evolving students’ ways of being so they become responsive, knowledgeable, ethical, and competent beginning practitioners” (Doane & Brown, 2011) [

34] (p. 50). This change in approach offers the ability to the student nurse to move from trainee to qualified professional and be ready for the demands required. Throughout this process it was claimed that “interpretative pedagogies encourage students to process the multiple perspectives that exist, which can lead to deeper thinking and promote shared learning, bringing students and teachers together in a community of learning (Kuiper, 2012)” [

34] (p. 50). Including “simulation-based learning as an approach to education that provides the learner with an opportunity to contextualize the information and emulate the practice setting” [

34] (p. 50) creates the opportunity to explore the requirements of the practice within the learning environment of the classroom. Again, similarities exist with informal education pedagogical approaches whereby the learning environment creates the space for shared learning to apply the theory to a practice context, where exploratory knowledge and understanding can be harnessed.

The literature discussed argues that student practice in the field is influenced by the pedagogical style they have experienced as McPherson and MacDonald clearly state:

“(simulation-based learning)…supports transition to practice and is more congruent with the needs of professional practice (Curtis, Sheerin, & Vries, 2011),…and ‘interpretative pedagogies’ help us to bridge the science and the art of practice-based professions (Gilkison, 2013), bringing health professional students from merely knowing to informed and effective action”.

Considering the notion that informal education pedagogy offers its purpose as to cultivate communities, associations and relationships that make for human flourishing [

1] it is argued that this has a place in the new post-pandemic world. In doing so the question remains of how this transcends into society at large, especially in those communities most impacted by the pandemic. To transcend such notions then considerations not just from the past and present but the future are needed, including drawing from the pandemic experience in such a way as to move on from the hardship faced by so many. As Rogers [

35] suggests, there are two main ways in which we all learn based on the ideas of Dewey: education as a process of living and education as a process for future living. The shift that the pandemic may have offered is towards the latter, education as a process for future living, in that informal education pedagogy can be presented as a realistic and useful approach to draw from, offering a more credible status across the education continuum.

The ‘messengers’ of such an approach are those placed within the relevant context of such knowledge and understanding, the students. This is how students can become ‘social justice champions’ personally, professionally, and societally (value-based theory into practice). As a reminder, ‘Informal Education’ is an educational practice which can occur in a number of settings, both institutional and non-institutional…and is…a practice undertaken by committed practitioners [

6] (p. 1), such committed practitioners being the students, as they move into the relevant practice settings and professional contexts where informal education pedagogy exists and can be considered. The array of settings and contexts, institutional and non-institutional, vary from the large local authority or charity whose organisational culture enables informal education pedagogy to become one of the many approaches used, to the small-scale local organisation that has a range of committed volunteers offering much needed activities and learning opportunities within communities. This is supported by the idea that informal educators go to meet people and start where those people are, with their own preoccupations and in their own places [

6] (p. 2). This supports the argument as to how transcending of the pedagogy takes place, both in its values and principles, but also in the approaches used. However, this may not be a straightforward task as many challenges could be faced by the informal educator in the post-pandemic world, not just from the health and well-being perspective, but from available allocated resources that could become more targeted than previously. However, returning to the arguments of Ford and Profetto-McGrath, they pose that: “praxis is not action that maintains the status quo, but rather action that changes ‘both the world and our understanding of it’ (Grundy, p. 113)” [

27] (p. 1). This is where informal education pedagogy can maintain its position, as part of the role of the informal educator is to keep the condition for conversation alive, even in situations of conflict [

6] (p. 8).

Keeping such conversations alive has been evidenced throughout history but also through the pandemic environment, with issues raised and brought to the public consciousness more succinctly such as the Black Lives Matter global campaigns emphasising major issues of concern regarding prejudices within mainstream institutions and how citizens are perceived and treated. As well as the loss of life, there has been a challenge to the social, political and economic discourse, underpinned by historical narratives, that has presented an unequal and prejudiced based view of life. This has resulted not just in many campaigns but also in the challenging of civic heritage, statues and other municipal artefacts. Furthermore, the exploration, and much needed, challenging of historical facts, as originally portrayed, in the literature that informs the current discourse, through such approach as decolonisation of education within the academy, is currently the focus of much attention as the HE curriculum is being reconfigured. Other such issues of concern have been the climate change debate, especially placed clearly in the public domain by young people such as Greta Thunberg, with a mass global following. The ability to champion, empower and enable young people to campaign on a key issue against the hegemonic rule of states, such as missing school or college, has been one that has shown that young people do have a voice. The use of ‘campaigns’ to present a shared voice has had mixed results, but the scale of influence and impact has shown that agency can be enacted, with Greta attending the various Climate Change Conferences. Placing this within the context of informal education pedagogy, it could be suggested that these young people stepped outside the usual conformist way of voicing their opinion and sought another. This is another example of where young people have created and gained their own agency in a collective way both to show their views and opinions, but also to challenge the current neo-liberal and capitalist way of thinking. A question posed by many young people is why they should go to school/college based upon an outdated economic system if their future is going to be bleak in relation to climate issues such as severe weather changes, increased poverty, animal species becoming extinct, the poorer getting poorer with the rich getting richer, and further inequalities. This can be noted where …in a shared engagement with everyday problem-posing, new learning occurs…because the learning is of immediate significance to those involved, rather than derived from a pre-established curriculum [

6] (p. 2). This immediate significance has been identified with the young people concerned but, it could be argued, not necessarily with those in power. The question posed could be, are young people citizens of today or tomorrow and is there any significance to this perception? The sometimes suggested apathy of the general public and their lack of interest in wider issues that may not directly affect them could be contradicted by the examples mentioned here. However, the understanding and perceptions of how a citizen is defined varies in differing contexts, culturally and politically. This was explored by Biesta et al. who argued:

“…rather than to blame individuals for an apparent lack of citizenship and civic spirit, we should start at the other end by asking about the actual opportunities for the enactment of the experiment of democracy that are available in our societies, on the assumption that participation in such practices can engender meaningful forms of citizenship and democratic agency”.

These meaningful forms of ‘citizenship and democratic agency’ [

36] exist where individuals come together through a shared concern and/or issue in challenging where the power of citizenship lies, as well as who determines what meaning is defined as.

It can be argued that many students themselves form part of this mass campaign in airing their views and opinions, and indirectly/directly become ‘social justice champions’. Many such students will be participating in professional practice settings as part of their learning experience, or working/volunteering additionally to their academic learning can be situations and contexts in which such informal education pedagogy exists. But does utilising such pedagogies suggest that an individual is also a ‘good citizen’? On the contrary, if such pedagogies were not drawn upon in reaching those most affected within society, then does this make the individual a ‘bad citizen’? It can be said that many ‘good citizen’ acts of kindness and support presented themselves more commonly throughout the pandemic, than would have happened in the pre-pandemic environment. This leads to the question;

“…whether the good citizen is the one who fits in, the one who goes with the flow and the one who is part of the whole, or whether the good citizen is the one who stands out from the crowd, the one who goes against the flow, the one who ‘bucks the trend’ and the one who, in a sense, is always slightly ‘out of order’”.

Asking such critical questions draws attention to how society treats citizens, as objects or subjects? If students are to become ‘social justice champions’, does this mean their role and function is somehow impacted upon, changed, differs from their predecessors? In a globally connected environment where people can immediately see, usually through social media platforms, the array of injustices taking place, then does this offer a purpose, for some, to challenge the current approach? Utilising informal education pedagogy as an approach through ‘social justice champion’ acts of agency may create and develop this sense of purpose through a mixture of new knowledge and previous experiences, in oneself as well others. As Dewey alluded to in his discussion of how experience and education are inherently linked and can offer an alternative philosophical way of learning for educators:

“The formation of purpose is, then, a rather complex intellectual operation. It involves (1) observation of surrounding conditions; (2) knowledge of what has happened in similar situations in the past, a knowledge obtained partly by recollection and partly from the information, advice, and warning of those who have had a wider experience; and (3) judgement which puts together what is observed and what is recalled to see what they signify”.

The combination of citizenship with agency and meaningful purpose could be the tools for students to enact a transcendence of the ‘social justice champion’ role and/or function within society utilising informal education pedagogy.

7. Conclusions

This discussion paper presented the overarching argument that informal education pedagogies within teaching and learning have significance both in the learning environment and in a practice context within society.

Firstly, it explored the notion that the academic role may have a ‘duality’ function through a combination of academic and practitioner activity. ‘Macro’ and ‘micro’ contexts were discussed, highlighting the marketised higher education environment where power and politics play out. Examples of informal education pedagogic concepts for teaching and learning within educational practices were presented for consideration. Secondly, it was argued that synergies between ‘pedagogies’, informal education pedagogy and social pedagogy, have the same value-base and draw upon the same range of methods/approaches. A comparative discussion offered concept examples of how they could be applied both in the classroom and the practice context. Next it was considered how informal education pedagogy could be drawn upon within differing learning settings, posing the argument, for example, of whether it could be utilised within a lecture theatre. This suggested that such teaching and learning pedagogy could be drawn upon in any setting and context as a vehicle to explore the subject matter. The discussion thread moved to the impact that the COVID pandemic has had upon society, including teaching and learning. It was identified, sharing examples, how informal education pedagogy was evident throughout the pandemic within society. Finally, arguments were posed that such pedagogy transcends into the wider society in how students become ‘social justice champions’ personally, professionally, and societally (value-based theory into practice). It argued that student practice in the field is influenced by the pedagogical style they have experienced within their learning.

The current pandemic has brought to the fore many inequalities and injustices, many already existing, but having been thrust into the ‘public eye’ with vivid examples across society. This has touched many aspects of everyday life for many people across health, education, financial security, employment, and poverty. However, it has also brought new ways in which people have related to each other, such as neighbours and work colleagues, within communities and society at large. An outpouring of support for institutions such as the National Health Service, social care, education, and front-line workers maintaining everyday services has also emerged, not necessarily recognised previously. An increased use of social functions such as flexibility, adaptability and change has taken place throughout the pandemic, but for those having the available social, cultural and financial capital, being able to draw upon such capital aids a reduced pandemic impact. The pandemic has also presented many examples of philanthropy for those most in need, supported from those known to them but also initially not known to them, drawing from the perspective of ‘human flourishing’ and a ‘caring nurture’ notion coming to the fore. Such philanthropy has been evident in many individuals but also other bodies, including many small to medium non-governmental organisations, working in communities with a range of issues from food poverty to education support and general well-being.

The value-based, person-centred and reflective elements of informal education pedagogy, and social pedagogy, could be those that can forge such changes. In forging such changes, it is clear that students could be the vehicles as ‘social justice champions’ in transcending informal education pedagogy, and taking it from the ‘academy’ to society, adding to the existing philanthropy. As Freire reminds us “in problem-posing education, people develop their power to perceive critically the way they exist in the world with and in which they find themselves; they come to see the world not as a static reality, but as a reality in process, in transformation” [

2] (p. 56).