Does a Strong Bicultural Identity Matter for Emotional, Cognitive, and Behavioral Engagement?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

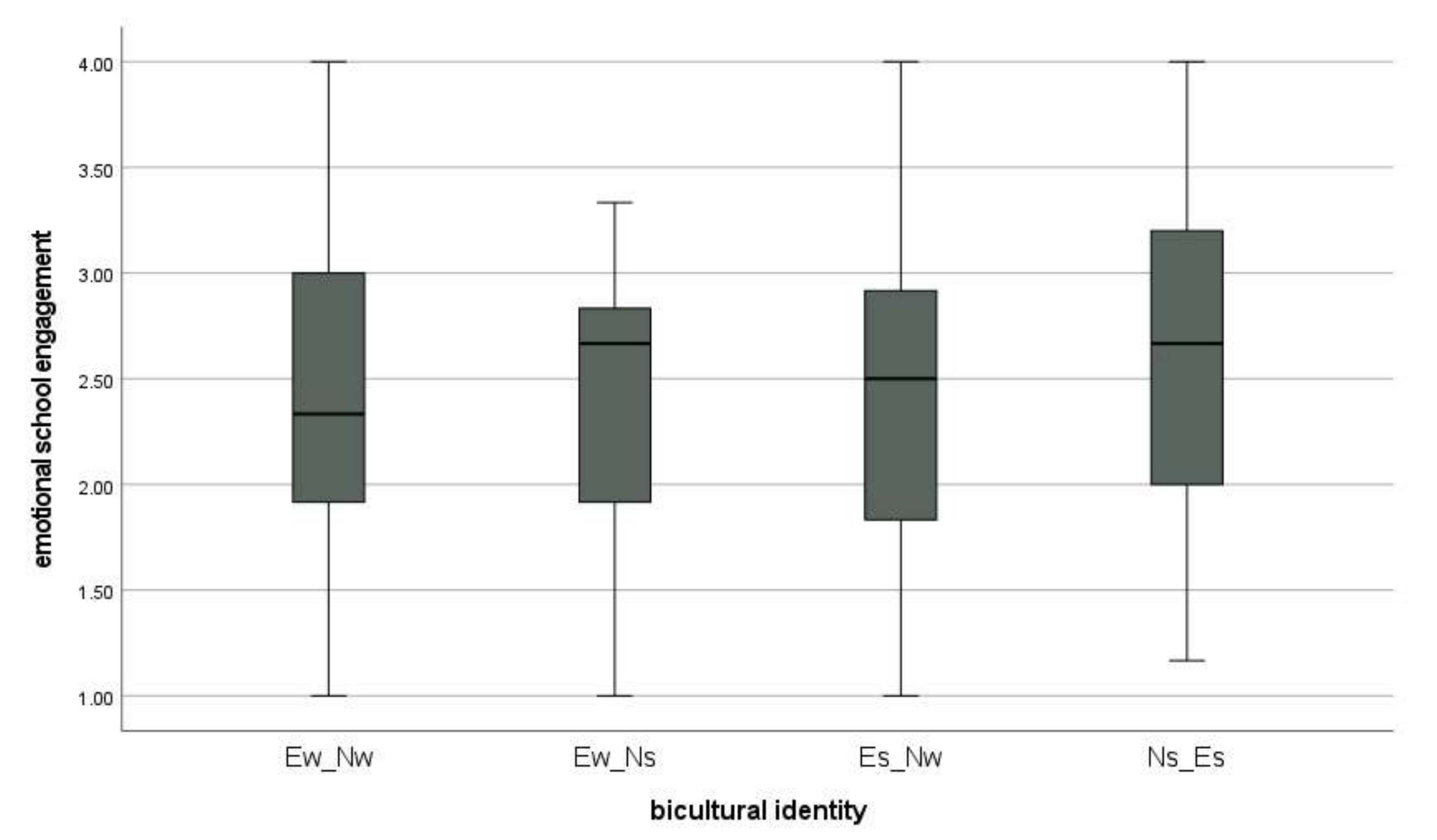

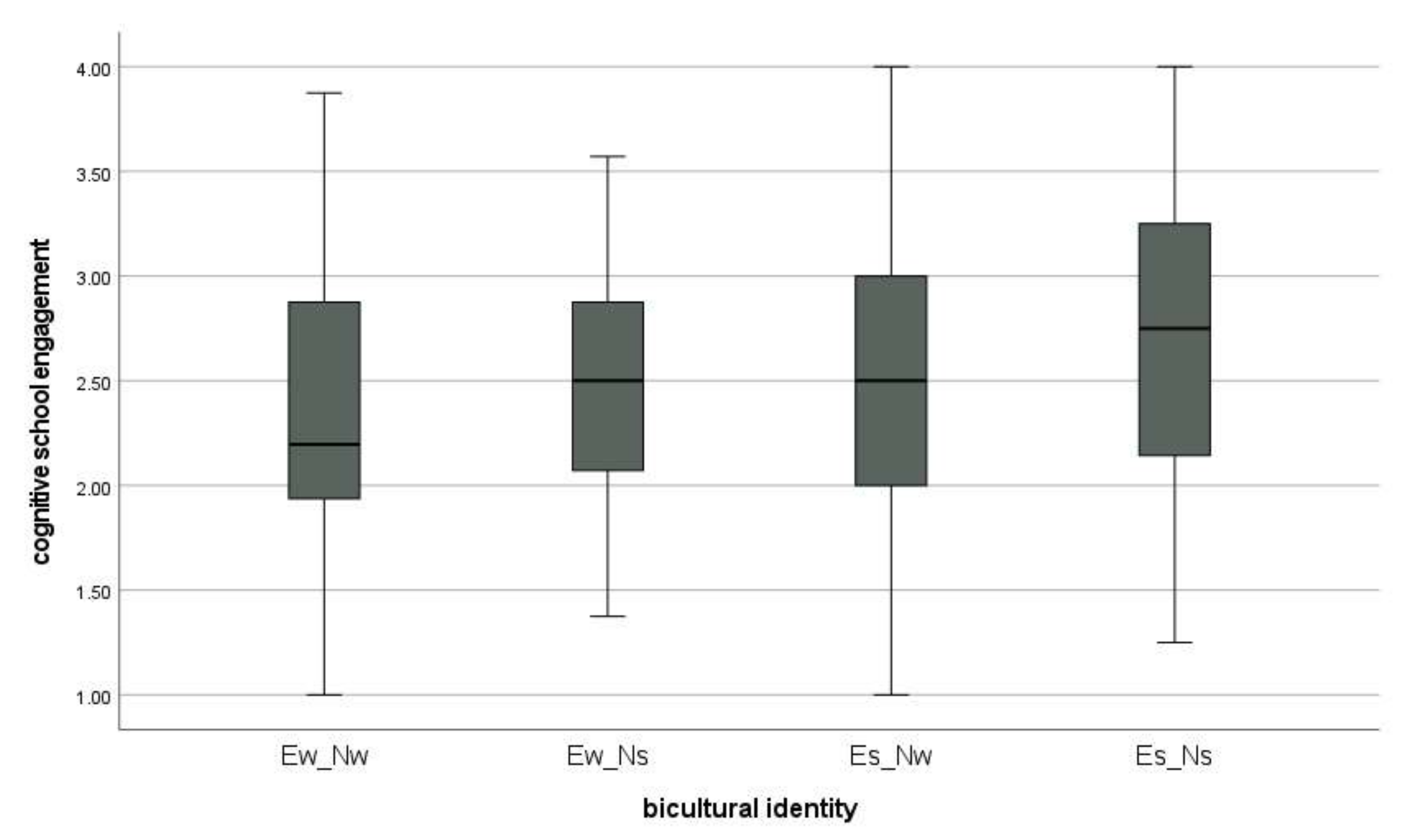

1.1. Bicultural Identity

1.2. Bicultural Identity and Well-Being

1.3. Bicultural Identity and School Engagement

1.4. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Analysis

2.3. Participants

2.4. Bicultural Group Comparison

2.5. Measure

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Göbel, K.; Buchwald, P. Interkulturalität und Schule: Migration—Heterogenität—Bildung; UTB: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, A.-T.D.; Benet-Martínez, V. Biculturalism and Adjustment. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2013, 44, 122–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesamt, S. Bevölkerung Und Erwerbstätigkeit. Bevölkerung und Migrationshintergrund—Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2017; Statistisches Bundesamt DESTATIS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chirkov, V. An introduction to the theory of sociocultural models. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 23, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, J.S. Ethic identity and Acculturation. In Acculturation: Advances in Theory, Measurement, and Applied Research; Chun, K.M., Organista, P.B., Marín, G., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; Volume 18, pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Vedder, P.; Phinney, J.S. Identity Formation in Bicultural Youth: A Developmental Perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Multicultural Identity; Benet-Martínez, V., Hong, Y.-Y., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 335–354. [Google Scholar]

- Vedder, P.; Horenczyk, G. Acculturation and the School. In The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology; Sam, D.L., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 419–438. [Google Scholar]

- Gutentag, T.; Horenczyk, G.; Tatar, M. Teachers’ Approaches toward Cultural Diversity Predict Diversity-Related Burnout and Self-Efficacy. J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W.; Phinney, J.S.; Sam, D.L.; Vedder, P. Immigration Youth: Acculturation, Identity, and Adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 55, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berry, J.W. Stress Perspectives on Acculturation. In The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology; Sam, D.L., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Vertovec, S. Super-diversity and Its Implications. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2006, 30, 1024–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.S.; Chu, H. Discrimination, ethnic identity, and academic outcomes of Mexican immigrant children: The importance of school context. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 1477–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, E.; Gilde, J.; Birman, D. Teachers as risk and resource factors in minority students’ school adjustment: An integrative review of qualitative research on acculturation. Intercult. Educ. 2019, 30, 448–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, G.; Tienda, M. Optimism and Achievement: The Educational Performance of Immigrant Youth. Soc. Sci. Q. 1995, 76, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Pisa 2015 Results—Students’ Well-Being III; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Başkaya, S.; Boos-Nünning, U. Bildungsbrücken Bauen: Stärkung der Bildungschancen von Kindern mit Migrationshintergrund; ein Handbuch für die Elternbildung; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J.D. Linguistic Interdependence and the Educational Development of Bilingual Children. Rev. Educ. Res. 1979, 49, 222–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-T.; Degol, J.L.; Henry, D.A. An integrative development-in-sociocultural-context model for children’s engagement in learning. Am. Psychol. 2019, 74, 1086–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habermas, T. Identitätsentwicklung im Jugendalter. Psychol. Jugendforsch. 2008, 5, 363–387. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oudenhoven, J.P.; Benet-Martínez, V. In search of a cultural home: From acculturation to frame-switching and intercultural competencies. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2015, 46, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Tajfel, H., Ed.; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; Volume 33, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zander, L.; Hannover, B. Die Bedeutung der Identifikation mit der Herkunftskultur und mit der Aufnahmekultur Deutschland für die soziale Integration Jugendlicher mit Migrationshintergrund in ihrer Schulklasse. Z. Entwickl. Pädagogische Psychol. 2013, 45, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña-Taylor, A.J. Ethnic identity. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, K.J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 791–809. [Google Scholar]

- Liebkind, K.; Jasinskaja-Lahti, I.; Solheim, E. Cultural Identity, Perceived Discrimination, and Parental Support as Determinants of Immigrants’ School Adjustments. J. Adolesc. Res. 2014, 19, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, J.S.; Horenczyk, G.; Liebkind, K.; Vedder, P. Ethnic Identity, Immigration, and Well-Being: An Interactional Perspective. J. Soc. Issues 2001, 57, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lilla, N.; Thürer, S.; Nieuwenboom, W.; Schüpbach, M. Exploring Academic Self-Concepts Depending on Acculturation Profile. Investigation of a Possible Factor for Immigrant Students’ School Success. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horenczyk, G. Language and Identity in the School Adjustment of Immigrant Students in Israel. Z. Padagog. 2010, 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Horenczyk, G.; Jasinskaja-Lahti, I.; Sam, D.; Vedder, P. Mutuality in Acculturation Toward an Integration. Z. Psychol. 2013, 4, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis, H.; Gelfand, M.A. theory of Individualism and collectivism. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; Van Lange, P.A.M., Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012; pp. 498–520. [Google Scholar]

- Phalet, K.; Claeys, W. A comparative study of Turkish and Belgian youth. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1993, 24, 319–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phalet, K.; Schönpflug, U. Intergenerational transmission in Turkish immigrant families: Parental collectivism, achievement values and gender differences. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2020, 32, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, S.; Deaux, K. The Bicultural Identity Performance of Immigrants Identity and Participation in Culturally Diverse Societies: A Multidisciplinary Perspective; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Jugert, P.; Titzmann, P.F. Trajectories of victimization in ethnic diaspora immigrant and native adolescents: Separating acculturation from development. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirkov, V. Alfred Schutz’s “Stranger,” the Theory of Sociocultural Models, in print. Available online: https://artsandscience.usask.ca/profile/VChirkov#Research (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Chirkov, V. The sociocultural movement in psychology, the role of theories in sociocultural inquiries, and the theory of sociocultural models. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 23, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirim, İ. Umgang mit migrationsbedingter Mehrsprachigkeit in der schulischen Bildung, Schule in der Migrationsgesellschaft. In Ein Handbuch; Leiprecht, R., Steinbach, A., Schwalbach, T., Eds.; Debus Pädagogik Verlag: Schwalbach am Taunus, Germany, 2015; pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, R.; Moore, H.; Astor, R.A.; Benbenishty, R.A. Research Synthesis of the Associations Between Socioeconomic Background, Inequality, School Climate, and Academic Achievement. Rev. Educ. Res. 2017, 87, 425–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azzi, A.E.; Chryssochoou, X.; Klandermans, B.; Simon, B. Identity and Participation in Culturally Diverse Societies. A Multidisciplinary Perspective; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Makarova, E.; Döring, A.K.; Auer, P.; Birman, D. School adjustment of ethnic minority youth: A qualitative and quantitative research synthesis of family-related risk and resource factors. Educ. Rev. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwald, P.; Hobfoll, S.E. Die Theorie der Ressourcenerhaltung: Implikationen für Stress und Kultur. In Handbuch Stress und Kultur; Ringeisen, T., Genkova, P., Leong, F.T.L., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Benner, A.D.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Boyle, A.E.; Polk, R.; Cheng, Y.P. Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: A meta-analytic review. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 855–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasinskaja-Lahti, I.; Liebkind, K.; Horenczyk, G.; Schmitz, P. The interactive nature of acculturation: Perceived discrimination, acculturation attitudes and stress among young ethnic repatriates in Finland, Israel and Germany. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2003, 27(1), 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulis, S.; Marsiglia, F.F.; Nieri, T. Perceived ethnic discrimination versus acculturation stress: Influences on substance use among Latino youth in the Southwest. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2009, 50, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Göbel, K.; Preusche, Z.M. Emotional school engagement among minority youth: The relevance of cultural identity, perceived discrimination, and perceived support. Intercult. Educ. 2019, 30, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuyten, M. The Integration Paradox: Empiric Evidence From the Netherlands. Am. Behav. Sci. 2016, 60, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Toro, J.; Hughes, D.; Way, N. Inter-Relations Between Ethnic-Racial Discrimination and Ethnic-Racial Identity Among Early Adolescents. Child Dev. 2021, 92, 106–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balidemaj, A.; Small, M. Acculturation, ethnic identity, and psychological well-being of Albanian-American immigrants in the United States. Int. J. Cult. Ment. Health 2018, 11, 712–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, E.; Hogge, I.; Salvisberg, C. Effects of Self-Esteem and Ethnic Identity. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2014, 36, 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vemde, L.; Hornstra, L.; Thijs, J. Classroom Predictors of National Belonging: The Role of Interethnic Contact and Teachers’ and Classmates’ Diversity Norms. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.J.; Molina, L.E. Is Pluralism a Viable Model of Diversity? The Benefits and Limits of Subgroup Respect. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2006, 9, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, S.X.; Benet-Martínez, V.; Harris-Bond, M. Bicultural identity, bilingualism, and psychological adjustment in multicultural societies: Immigration-based and globalization-based acculturation. J. Personal. 2008, 76, 803–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkuyten, M.; Martinovic, B. Social identity complexity and immigrants’ attitude towards the host nation: The intersection of ethnic and religious group identification. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenni Hoti, A.; Heinzmann, S.; Müller, M.; Buholzer, A. Psychosocial adaptation and school success of Italian, Portuguese and Albanian students in Switzerland: Disentangling migration background, acculturation and the school context. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2017, 18, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klylioglu, L.; Heinz, W. The Relationship Between Immigration, Acculturation and Psychological Well Being. Nesne Psikoloji Dergisi 2015, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bandorski, S. Ethnische Identität als Ressource für die Bildungsbeteiligung? Bildungsforschung 2008, 5, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgramm, C.; Morf, C.C.; Hannover, B. Ethnically based rejection sensitivity and academic achievement: The danger of retracting into one’s heritage culture. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 44, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, E.; Herzog, W. Hidden School Dropout among Immigrant Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Intercult. Educ. 2013, 24, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuller-Rowell, T.E.; Ong, A.D.; Phinney, J.S. National Identity and Perceived Discrimination Predict Changes in Ethnic Identity Commitment: Evidence from a Longitudinal Study of Latino College Students. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 62, 406–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, J.S.; Devich-Navarro, M. Variations in bicultural identification among African American and Mexican American adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 1997, 7, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edele, A.P.; Stanat, S.; Radmann, M.; Segeritz, M. Kulturelle Identität Und Lesekompetenz Von Jugendlichen Aus Zugewanderten Familien. In PISA 2009—Impulse für Die Schul- und Unterrichtsforschung; Jude, N., Klieme, E., Eds.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2013; pp. 84–110. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 46, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, L.E.; Phillips, N.L.; Sidanius, J. National and ethnic identity in the face of discrimination: Ethnic minority and majority perspectives. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 2015, 21, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Branscombe, N.R.; Schmitt, M.T.; Harvey, R.D. Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African-Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunyu, D.K.; Juang, L.P.; Schachner, M.K.; Schwarzenthal, M. Discrimination among youth of immigrant descent in Germany: Do school and cultural belonging weaken links to negative socio-emotional and academic adjustment? Ger. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 52, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris-Britt, A.; Valrie, C.R.; Kurtz-Costes, B.; Rowley, S.J. Perceived Racial Discrimination and Self-Esteem in African American Youth: Racial Socialization as a Protective Factor. J. Res. Adolesc. Off. J. Soc. Res. Adolesc. 2007, 17, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spiegler, O.; Sonnenberg, K.; Fassbender, I.; Kohl, K.; Leyendecker, B. Ethnic and Naitonal Identity Development and School Adjustment: A Longitudinal Study with Turkish Immigrant Origin Children. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2018, 49, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumert, J.; Watermann, R.; Schümer, G. Disparitäten der Bildungsbeteiligung und des Kompetenzerwerbs. Z. Erzieh. 2003, 6, 46–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, K. Bildungsgerechtigkeit. Rekonstruktionen eines Umkämpften Begriffs; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kunyu, D.K.; Schachner, M.K.; Juang, L.P.; Schwarzenthal, M.; Aral, T. Acculturation hassles and adjustment of adolescents of immigrant descent: Testing mediation with a self-determination theory approach. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2021, 177, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, F.; Phalet, K. Integration and religiosity among the Turkish second generation in Europe: A comparative analysis across four capital cities. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2018, 35, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walton, G.M.; Cohen, G.L.; Cwir, D.; Spencer, S.J. Mere belonging: The power of social connections. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steele, C.M.; Aronson, J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiny, S.E.; Götz, T.; Keller, M. Emotionsregulation im Kontext von Stereotype Threat: Die Reduzierung der Effekte negativer Stereotype bei ethnischen Minderheiten. In Handbuch Stress und Kultur; Ringeisen, T., Genkova, P., Leong, F.T.L., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fredericks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.; Friedel, J.; Paris, A. School engagement. In What Do Children Need to Flourish?: Conceptualizing and Measuring Indicators of Positive Development; Moore, K.A., Lippman, L., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 305–321. [Google Scholar]

- Makarova, E.; Herzog, W. Teachers’ Acculturation Attitudes and Their Classroom Management: An Empirical Study among Fifth-Grade Primary School Teachers in Switzerland. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 12, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raufelder, D.; Hoferichter, F.; Ringeisen, T.; Regner, N.; Jacke, C. The Perceived Role of Parental Support and Pressure in the Interplay of Test Anxiety and School Engagement Among Adolescents: Evidence for Gender-Specific Relations. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2014, 24, 3742–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reschly, A.L.; Christenson, S.L. Jingle, Jangle, and Conceptual Haziness: Evolution and Future Directions of the Engagement Construct. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Christenson, S.L., Reschly, A.L., Wylie, Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Perdue, N.H.; Manzeske, D.P.; Estell, D.B. Early predictors of school engagement: Exploring the role of peer relationships. Psychol. Schs. 2009, 46, 1084–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2014, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiu, M.M.; Pong, S.L.; Mori, I.; Chow, B.W.Y. Immigrant students’ emotional and cognitive engagement at school: A multilevel analysis of students in 41 countries. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 1409–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia-Reid, P.; Peterson, C.H.; Reid, R.J. Parent and Teacher Support Among Latino Immigrant Youth. Educ. Urban Soc. 2015, 47, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S. The effects of the teacher–student relationship and academic press on student engagement and academic performance. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2012, 53, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benbow, A.E.F.; Aumann, L.; Paizan, M.A.; Titzmann, P.F. Everybody needs somebody: Specificity and commonality in perceived social support trajectories of immigrant and non-immigrant youth. N. Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2021, 176, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Zabala, A.; Goñi, E.; Camino, I.; Zulaika, L.M. Family and school context in school engagement. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 9, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brewster, A.B.; Bowen, G.L. Teacher Support and the School Engagement of Latino Middle and High School Students at Risk of School Failure. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2004, 21, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civitillo, S.; Göbel, K.; Preusche, Z.M.; Jugert, P. Disentangling the effects of perceived personal and group ethnic discrimination among secondary school students: The protective role of teacher-student relationship quality and school climate. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2021, 177, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Civitillo, S.; Juang, L. How to best prepare teachers for multicultural schools: Challenges and perspectives. In Youth in Super Diverse Societies: Growing up with Globalization, Diversity, and Acculturation; Titzmann, P.F., Jugert, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Vietze, J.; Juang, L.P.; Schachner, M.K. Peer cultural socialisation: A resource for minority students’ cultural identity, life satisfaction, and school values. Intercult. Educ. 2019, 30, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schachner, M.K.; Juang, L.; Moffitt, U.; van de Vijver, F.J. Schools as acculturative and developmental contexts for youth of immigrant and refugee background. Eur. Psychol. 2018, 23, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, K.; Frankemölle, B. Interkulturalität und Wohlbefinden im Schulkontext. In Handbuch Stress und Kultur; Ringeisen, T., Genkova, P., Leong, F.T.L., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Özdemir, S.B.; Özdemir, M. The role of perceived inter-ethnic classroom climate in adolescents’ engagement in ethnic victimization: For whom does it work? J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 1328–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abacioglu, C.S.; Zee, M.; Hanna, F.; Soeterik, I.M.; Fischer, A.H.; Volman, M. Practice what you preach: The moderating role of teacher attitudes on the relationship between prejudice reduction and student engagement. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 86, 102887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysu, G.; Phalet, K. The Up- and Downside of Dual Identity: Stereotype Threat and Minority Performance. J. Soc. Issues 2019, 75, 568–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannover, B.; Morf, C.C.; Neuhaus, J.; Rau, M.; Wolfgramm, C.; Zander-Musić, L. How immigrant adolescents’ self-views in school and family context relate to academic success in Germany. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H. Ethnic Identity and Perceived Discrimination as Predictors of Academic Attitudes: The Moderating and Mediating Roles of Psychological Distress and Self-Regulation. Master’s Thesis, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shernoff, D.J.; Schmidt, J.A. Further Evidence of an Engagement–Achievement Paradox among U.S. High School Students. J. Youth Adolesc. 2008, 37, 564–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation and adaptation: A general framework. In Mental Health of Immigrants and Refugees; Holtzman, W.H., Bornemann, T.H., Eds.; Hogg Foundation for Mental Health: Austin, TX, USA, 1990; pp. 90–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ganzeboom, H.B.G.; De Graaf, P.M.; Treiman, D.J. A Standard International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status. Soc. Sci. Res. 1992, 21, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kunter, M. PISA 2000. Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente; Max-Planck-Inst. für Bildungsforschung: Berlin, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney, J. The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A new scale for use with adolescents and young adults from diverse groups. J. Adolesc. Res. 1992, 7, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.; Phinney, J.S.; Masse, L.; Chen, Y.; Roberts, C.; Romero, A. The Structure of Ethnic Identity of Young Adolescents from Diverse Ethnocultural Groups. J. Early Adolesc. 1999, 19, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, L.-t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, K.; Lewandowska, Z.M.; Diehr, B. Lernziel Interkulturelle Kompetenz—Lernangebote Im Englischunterricht Der Klassenstufe 9—Eine Reanalyse Der Unterrichtsvideos Der DESI-Studie. Z. Fremdspr. 2017, 22, 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Juang, L.P.; Schachner, M.K.; Pevec, S.; Moffitt, U. The Identity Project intervention in Germany: Creating a climate for reflection, connection, and adolescent identity development. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2020, 173, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berliner Institut für Empirische Integrations- und Migrationsforschung (BIM). Wie Lehrkräfte Gute Leistung Fördern können. Forschungsbereich beim Sachverständigenrat Deutscher Stiftungen für Integration und Migration (SVR-Forschungsbereich); Vielfalt im Klassenzimmer: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, G.M.; Crum, A.J. Handbook of Wise Interventions; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schachner, M.K.; Noack, P.; van de Vijver, F.J.R.; Eckstein, K. Cultural Diversity Climate and Psychological Adjustment at School-Equality and Inclusion Versus Cultural Pluralism. Child Dev. 2016, 87, 1175–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachner, M.K.; Schwarzenthal, M.; van de Vijver, F.J.R.; Noack, P. How all students can belong and achieve: Effects of the cultural diversity climate amongst students of immigrant and nonimmigrant background in Germany. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 111, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, S.; Kneer, J.; Kovacs, C. Preservice teachers’ implicit attitudes toward students with and without immigration background: A pilot study. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2013, 39, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenthal, M.; Schachner, M.K.; van de Vijver, F.J.R.; Juang, L.P. Equal but different: Effects of equality/inclusion and cultural pluralism on intergroup outcomes in multiethnic classrooms. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 2018, 24, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Scale | Statistics | Source/Item Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional Engagement | 6 items, α = 0.839, M = 2.50, SD = 0.74, n = 444, 4-point-Likert scale (completely disagree to completely agree) | Fredricks et al. [79] (adapted); e.g., “I feel happy in school.” |

| Cognitive Engagement | 7 items, α = 0.679, M = 2.54, SD = 0.67, n = 445, 4-point-Likert scale (completely disagree to completely agree) | Fredricks et al. [79] (adapted); e.g., “I study at home even when I don’t have a test.” |

| Behavioral Engagement | 8 items, α = 0.801, M = 3.28, SD = 0.47, n = 446, 4-point Likert scale (completely disagree to completely agree) | Fredricks et al. [79] (adapted); e.g., “I pay attention in class.” |

| National Identity | 4 items, α = 0.932, M = 3.11, SD = 1.20, n = 361, 5-point Likert scale (completely disagree to completely agree) | Berry et al. [10] based on Phinney [101] and Roberts et al. [102]; e.g., “I am proud of being German.” |

| Ethnic Identity | 4 items, α = 0.887, M = 4.39, SD = 0.82, n = 324, 5-point Likert scale | Berry et al. [10] based on Phinney [101] and Roberts et al. [102]; e.g., “I am proud of being a member of my heritage culture.” |

| Model 0 | Model 1a | Model 1b | Model 1c | Model 1d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | β | β | β | β | |

| BI_Ew_Nw | −0.051 | ||||

| BI_Ew_Ns | −0.027 | ||||

| BI_Es_Nw | −0.092 | ||||

| BIt_Es_Ns | 0.151 * | ||||

| gender | 0.008 | −0.008 | −0.010 | −0.002 | 0.002 |

| HISEI | 0.063 | 0.052 | 0.048 | .042 | 0.051 |

| cult. capital | 0.237 ** | 0.236 ** | 0.241 ** | 0.227 ** | 0.223 ** |

| adjusted R2 | 0.059 | 0.054 | 0.052 | 0.060 | 0.074 |

| Model 0 | Model 1a | Model 1b | Model 1c | Model 1d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | β | β | β | β | |

| BI_Ew_Nw | −0.115 * | ||||

| BI_Ew_Ns | −0.040 | ||||

| BI_Es_Nw | −0.003 | ||||

| BI_Es_Ns | 0.106 * | ||||

| gender | 0.002 | 0.003 | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.008 |

| HISEI | −0.003 | 0.024 | 0.013 | 0.023 | 0.015 |

| cult. capital | 0.346 ** | 0.317 ** | 0.326 ** | 0.321 ** | 0.310 ** |

| adjusted R2 | 0.093 | 0.108 | 0.096 | 0.094 | 0.106 |

| Model 0 | Model 1a | Model 1b | Model 1c | Model 1d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | β | β | β | β | |

| BI_Ew_Nw | −0.041 | ||||

| BI_Ew_Ns | −0.082 | ||||

| BI_Es_Nw | −0.039 | ||||

| BI_Es_Ns | 0.113 * | ||||

| gender | 0.068 | 0.080 | 0.075 | 0.082 | 0.086 |

| HISEI | 0.008 | −0.006 | −0.009 | −0.012 | −0.008 |

| cult. capital | 0.301 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.291 ** | 0.277 ** | 0.270 ** |

| adjusted R2 | 0.091 | 0.079 | 0.084 | 0.079 | 0.090 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Preusche, Z.M.; Göbel, K. Does a Strong Bicultural Identity Matter for Emotional, Cognitive, and Behavioral Engagement? Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12010005

Preusche ZM, Göbel K. Does a Strong Bicultural Identity Matter for Emotional, Cognitive, and Behavioral Engagement? Education Sciences. 2022; 12(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12010005

Chicago/Turabian StylePreusche, Zuzanna M., and Kerstin Göbel. 2022. "Does a Strong Bicultural Identity Matter for Emotional, Cognitive, and Behavioral Engagement?" Education Sciences 12, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12010005

APA StylePreusche, Z. M., & Göbel, K. (2022). Does a Strong Bicultural Identity Matter for Emotional, Cognitive, and Behavioral Engagement? Education Sciences, 12(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12010005