What Matters for Boys Does Not Necessarily Matter for Girls: Gender-Specific Relations between Perceived Self-Determination, Engagement, and Performance in School Mathematics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Perceived Support for Self-Determination in the Classroom

1.2. Cognitive and Behavioral Engagement

1.3. Sustained Attention

1.4. Interrelations between these Bariables and the Role of Gender

2. The Present Study

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

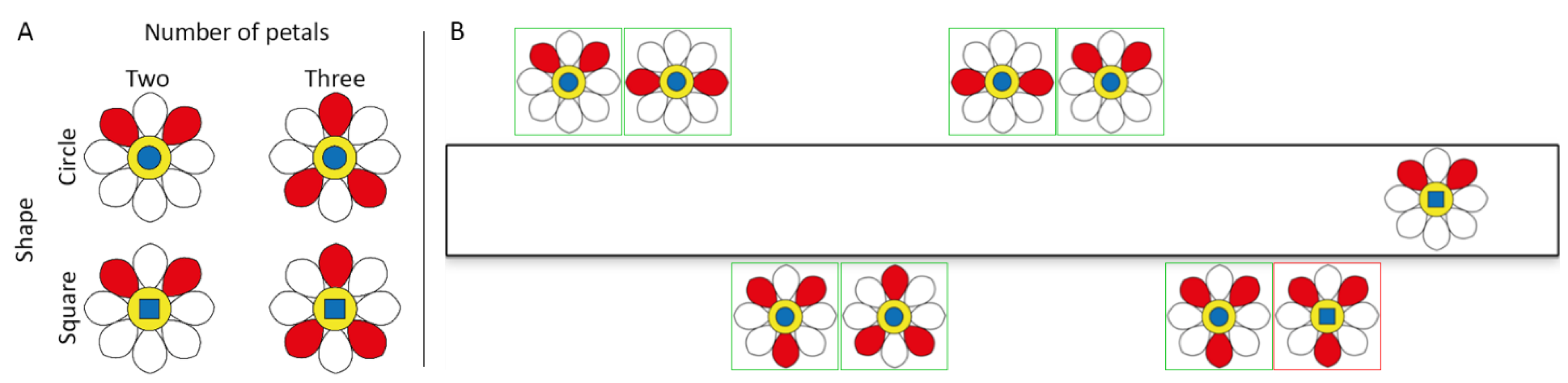

3.2. Instruments and Scales

3.3. Statistical Analysis

3.4. Transparency and Openness

4. Results

4.1. Basic Gender Differences

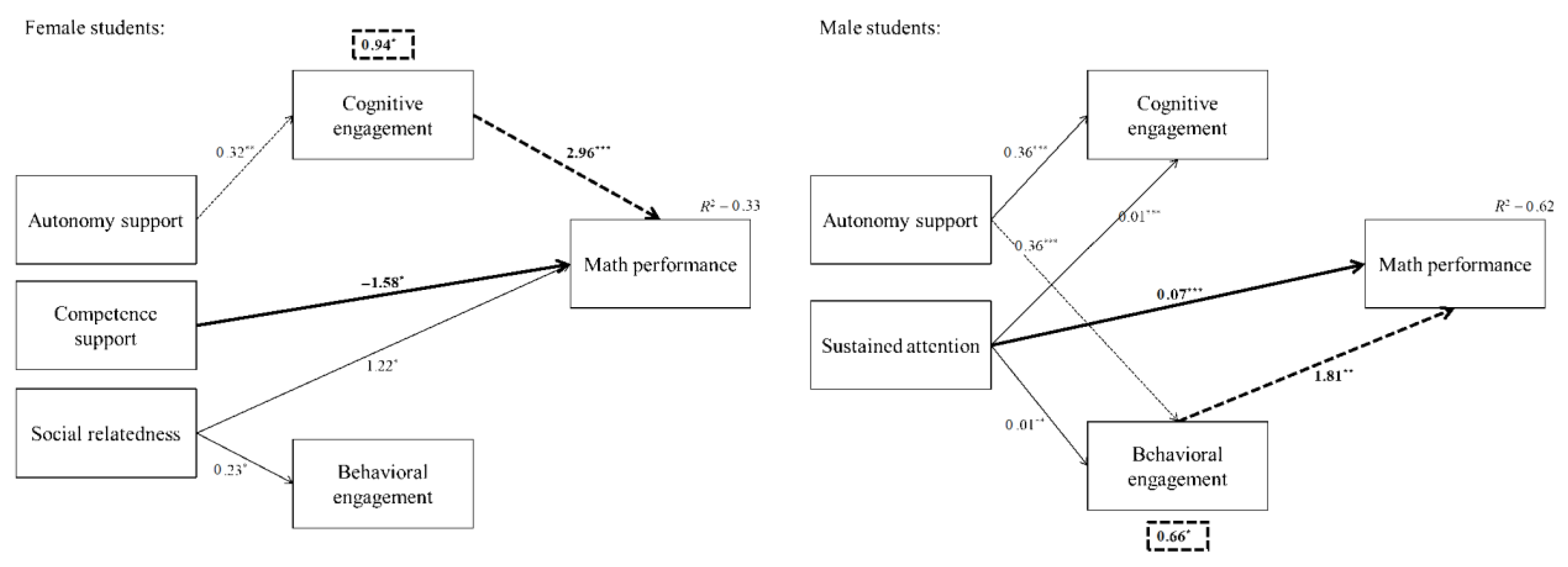

4.2. Main Multiple Group Path Analysis

4.3. Extended Multiple Group Path Analysis including Sustained Attention Based on Reduced Sample

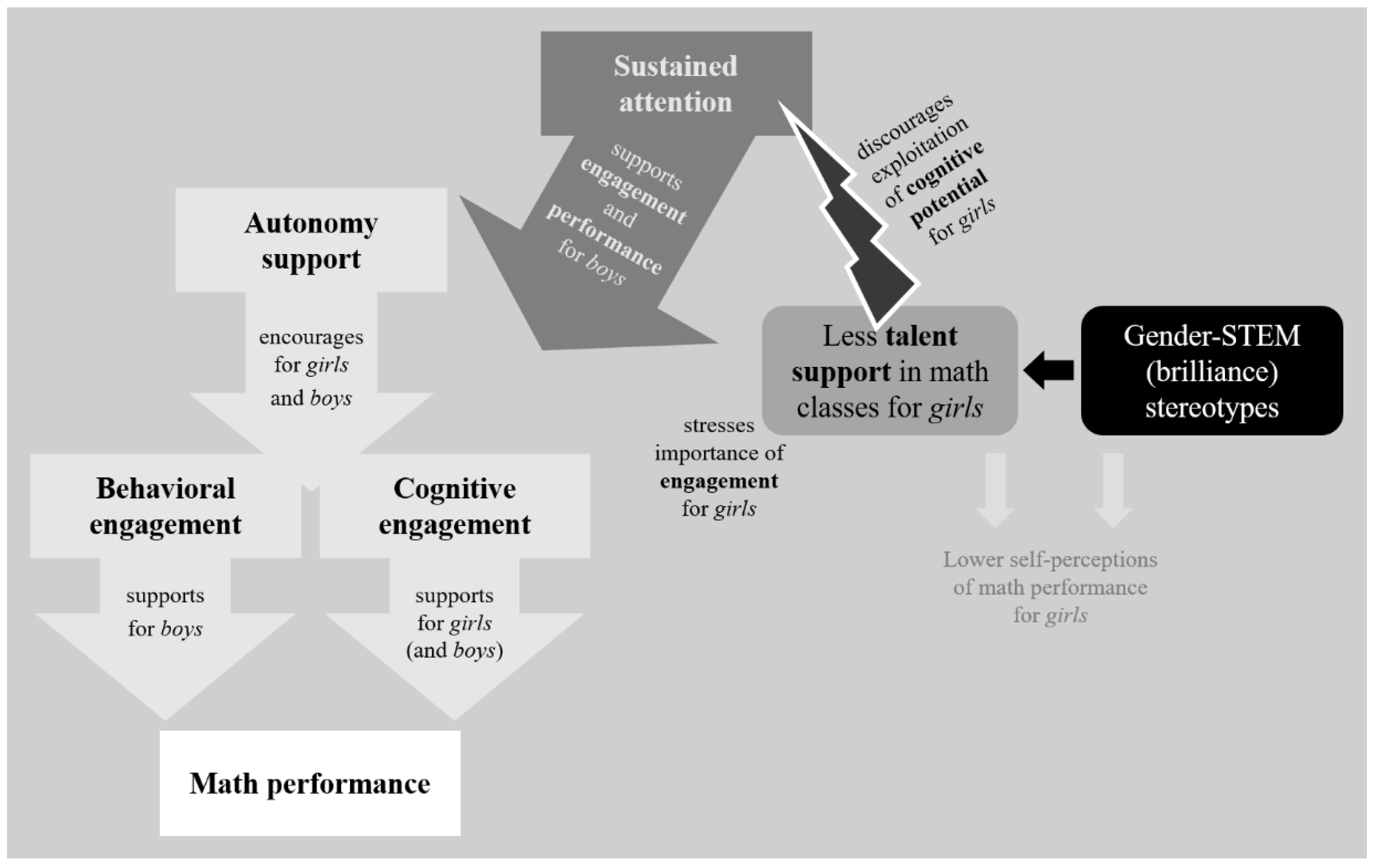

5. Discussion

5.1. The Paths Predicting Math Performance

5.2. Limitations and Implications for Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ceci, S.J.; Ginther, D.K.; Kahn, S.; Williams, W.M. Women in academic science: A changing landscape. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest J. Am. Psychol. Soc. 2014, 15, 75–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Halpern, D.F. It’s complicated-in fact, it’s complex: Explaining the gender gap in academic achievement in science and math. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest J. Am. Psychol. Soc. 2014, 15, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, D.F.; Benbow, C.P.; Geary, D.C.; Gur, R.C.; Hyde, J.S.; Gernsbacher, M.A. The science of sex differences in science and math. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest J. Am. Psychol. Soc. 2007, 8, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hyde, J.S. The gender similarities hypothesis. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stewart-Williams, S.; Halsey, L.G. Men, women, and STEM: Why the differences and what should be done? Eur. J. Personal. 2021, 35, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoet, G.; Geary, D.C. The gender-equality paradox in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 29, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, M.T.; Degol, J. Motivational pathways to STEM career choices: Using expectancy–value perspective to understand individual and gender differences in STEM fields. Dev. Rev. 2013, 33, 304–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, J.I. An overview of employment and wages in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) groups. Beyond Numbers Employ. Unempl. 2014, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, J.R.; Alfeld, C.; Pearson, D. Rigor and Relevance: Enhancing High School Students’ Math Skills Through Career and Technical Education. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2008, 45, 767–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimpian, J.R.; Kim, T.H.; McDermott, Z.T. Understanding persistent gender gaps in STEM. Science 2020, 368, 1317–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, J.S.; Lindberg, S.M.; Linn, M.C.; Ellis, A.B.; Williams, C.C. Gender similarities characterize math performance. Science 2008, 321, 494–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosek, B.A.; Banaji, M.R.; Greenwald, A.G. Math = Male, Me = Female, therefore Math ≠ Me. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L. The interplay among stereotypes, performance-avoidance goals, and women’s math performance expectations. Sex Roles 2006, 54, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, S.-J.; Cimpian, A.; Meyer, M.; Freeland, E. Expectations of brilliance underlie gender distributions across academic disciplines. Science 2015, 347, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ceci, S.J.; Williams, W.M. Sex differences in math-intensive fields. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 19, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Else-Quest, N.M.; Hyde, J.S.; Linn, M.C. Cross-national patterns of gender differences in math: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez, S.; Regueiro, B.; Piñeiro, I.; Estévez, I.; Valle, A. Gender differences in math motivation: Differential effects on performance in primary education. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindberg, S.M.; Hyde, J.S.; Petersen, J.L.; Linn, M.C. New trends in gender and math performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 1123–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sewasew, D.; Schroeders, U.; Schiefer, I.M.; Weirich, S.; Artelt, C. Development of sex differences in math achievement, self-concept, and interest from grade 5 to 7. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 54, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Hao, Y. Gender differences in math achievement in Beijing: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 88, 566–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, F.; Reiss, K.; Diedrich, J.; Hofer, S.I.; Heinze, A. Mathematische Kompetenz in PISA 2018—Aktueller Stand Und Entwicklung [Math Competence in PISA 2018—Current Status and Development]. In PISA 2018. Grundbildung im Internationalen Vergleich; Reiss, K., Weis, M., Klieme, E., Köller, O., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2019; pp. 187–210. [Google Scholar]

- Downey, D.B.; Vogt Yuan, A.S. Sex differences in school performance during high school: Puzzling patterns and possible explanations. Sociol. Q. 2005, 46, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyer, D.; Voyer, S.D. Gender differences in scholastic achievement: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1174–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Hofkens, T.; Wang, M.-T.; Mortenson, E.; Scott, P. Supporting girls’ and boys’ engagement in math and science learning: A mixed methods study. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2018, 55, 271–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiefele, U. The role of interest in motivation and learning. In Intelligence and Personality: Bridging the Gap in Theory and Measurement; Collins, J.M., Messick, S., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 163–194. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. The development of competence beliefs, expectancies for success, and achievement values from childhood through adolescence. In Development of Achievement Motivation; Wigfield, A., Eccles, J.S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 91–120. [Google Scholar]

- Blotenberg, I.; Schmidt-Atzert, L. Towards a process model of sustained attention tests. J. Intell. 2019, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schweizer, K.; Moosbrugger, H. Attention and working memory as predictors of intelligence. Intelligence 2004, 32, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbuto, J.E.; Scholl, R.W. Motivation sources inventory: Development and validation of new scales to measure an integrative taxonomy of motivation. Psychol. Rep. 1998, 82, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S. Studying the development of learning and task motivation. Learn. Instr. 2005, 15, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S.; Fredricks, J.A.; Simpkins, S.; Roeser, R.W.; Schiefele, U. Development of achievement motivation and engagement. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science; Lerner, R.M., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–44. ISBN 978-1-118-96341-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroet, K.; Opdenakker, M.-C.; Minnaert, A. Effects of need supportive teaching on early adolescents’ motivation and engagement: A review of the literature. Educ. Res. Rev. 2013, 9, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, J.; Watt, H.M.G. Perception shapes experience: The influence of actual and perceived classroom environment dimensions on girls’ motivations for science. Learn. Environ. Res. 2013, 16, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory. In The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation; Ryan, R.M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 84–108. ISBN 978-0-19-539982-0. [Google Scholar]

- Black, A.E.; Deci, E.L. The effects of instructors’ autonomy support and students’ autonomous motivation on learning organic chemistry: A self-determination theory perspective. Sci. Educ. 2000, 84, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Grolnick, W.S. Origins and pawns in the classroom: Self-report and projective assessments of individual differences in children’s perceptions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froiland, J.M.; Davison, M.L.; Worrell, F.C. Aloha teachers: Teacher autonomy support promotes native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander students’ motivation, school belonging, course-taking and math achievement. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2016, 19, 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, M.; Sancho, P.; Galiana, L.; Tomás, J.M. Autonomy support, psychological needs satisfaction, school engagement and academic success: A mediation model. Univ. Psychol. 2018, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wagner, M.; Christiano, E.R.A.; Shattuck, P.; Yu, J.W. Special Education Services Received by Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders from Preschool through High School. J. Spec. Educ. 2014, 48, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szulawski, M.; Kaźmierczak, I.; Prusik, M. Is self-determination good for your effectiveness? A study of factors which influence performance within self-determination theory. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, F.; Ratelle, C.F.; Chanal, J. Optimal learning in optimal contexts: The role of self-determination in education. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 2008, 49, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patall, E.A.; Steingut, R.R.; Freeman, J.L.; Pituch, K.A.; Vasquez, A.C. Gender disparities in students’ motivational experiences in high school science classrooms. Sci. Educ. 2018, 102, 951–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syzmanowicz, A.; Furnham, A. Gender differences in self-estimates of general, mathematical, spatial and verbal intelligence: Four meta analyses. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2011, 21, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, L.; Höhne, E.; Harms, S.; Pfost, M.; Hornsey, M.J. When grades are high but self-efficacy is low: Unpacking the confidence gap between girls and boys in math. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 552355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvencek, D.; Meltzoff, A.N.; Greenwald, A.G. Math-gender stereotypes in elementary school children. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 766–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, C. Effect of teachers’ stereotyping on students’ stereotyping of math as a male domain. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 141, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Zuo, B.; Wen, F.; Yan, L. Math-gender stereotypes and career intentions: An application of expectancy–value theory. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2017, 45, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Cimpian, J.P.; Lubienski, S.T.; Ganley, C.M.; Copur-Gencturk, Y. Teachers’ perceptions of students’ math proficiency may exacerbate early gender gaps in achievement. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 1262–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Appleton, J.J.; Christenson, S.L.; Kim, D.; Reschly, A.L. Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the Student Engagement Instrument. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 44, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkatsas, A.T.; Kasimatis, K.; Gialamas, V. Learning secondary mathematics with technology: Exploring the complex interrelationship between students’ attitudes, engagement, gender and achievement. Comput. Educ. 2009, 52, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, F.; Tan, C.Y.; Chen, G. Student engagement and mathematics achievement: Unraveling main and interactive effects. Psychol. Sch. 2018, 55, 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.A.; Furrer, C.; Marchand, G.; Kindermann, T. Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: Part of a larger motivational dynamic? J. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 100, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greene, B.A. Measuring cognitive engagement with self-report scales: Reflections from over 20 years of research. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 50, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; McColskey, W. The measurement of student engagement: A comparative analysis of various methods and student self-report instruments. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Christenson, S.L., Reschly, A.L., Wylie, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 763–782. ISBN 978-1-4614-2017-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, K.S. Eliciting engagement in the high school classroom: A mixed-methods examination of teaching practices. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 51, 363–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.K.; Crosnoe, R.; Elder, G.H. Students’ attachment and academic engagement: The role of race and ethnicity. Sociol. Educ. 2001, 74, 318–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.; Jimerson, S.; Kikas, E.; Cefai, C.; Veiga, F.H.; Nelson, B.; Hatzichristou, C.; Polychroni, F.; Basnett, J.; Duck, R. Do girls and boys perceive themselves as equally engaged in school? The results of an international study from 12 countries. J. Sch. Psychol. 2012, 50, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamote, C.; Speybroeck, S.; Van Den Noortgate, W.; Van Damme, J. Different pathways towards dropout: The role of engagement in early school leaving. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2013, 39, 739–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietaert, S.; Roorda, D.; Laevers, F.; Verschueren, K.; De Fraine, B. The gender gap in student engagement: The role of teachers’ autonomy support, structure, and involvement. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 85, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, H.M. Student engagement in instructional activity: Patterns in the elementary, middle, and high school years. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2000, 37, 153–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombie, G.; Pyke, S.W.; Silverthorn, N.; Jones, A.; Piccinin, S. Students’ perceptions of their classroom participation and instructor as a function of gender and context. J. High. Educ. 2003, 74, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, F.; Strohmaier, A.; Hoch, S.; Reiss, K.; Böheim, R.; Seidel, T. Process Data from Electronic Textbooks Indicate Students’ Classroom Engagement. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2020, 83–84, 101934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, L.M.; Kannass, K.N.; Shaddy, D.J. Developmental changes in endogenous control of attention: The role of target familiarity on infants’ distraction latency. Child Dev. 2002, 73, 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmayr, R.; Ziegler, M.; Träuble, B. Do intelligence and sustained attention interact in predicting academic achievement? Learn. Individ. Differ. 2010, 20, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarter, M.; Givens, B.; Bruno, J.P. The cognitive neuroscience of sustained attention: Where top-down meets bottom-up. Brain Res. Rev. 2001, 35, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, M.I.; Zhe, E.J.; Haugen, K.A.; Klein, J.A. Self-management of on-task homework behavior: A promising strategy for adolescents with attention and behavior problems. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 38, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, T.; Burstein, K.; Bryan, J. Students with learning disabilities: Homework problems and promising practices. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 36, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wu, Y.; Fossella, J.A.; Posner, M.I. Assessing the heritability of attentional networks. BMC Neurosci. 2001, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banz, B.C.; Wu, J.; Crowley, M.J.; Potenza, M.N.; Mayes, L.C. Gender-related differences in inhibitory control and sustained attention among adolescents with prenatal cocaine exposure. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2016, 89, 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, R.C.K. A further study on the sustained attention response to task (SART): The effect of age, gender and education. Brain Inj. 2001, 15, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatter, K.; Graw, P.; Münch, M.; Knoblauch, V.; Wirz-Justice, A.; Cajochen, C. Gender and age differences in psychomotor vigilance performance under differential sleep pressure conditions. Behav. Brain Res. 2006, 168, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; He, Y.; Qinglin, Z.; Chen, A.; Li, H. Gender differences in behavioral inhibitory control: ERP evidence from a two-choice oddball task. Psychophysiology 2008, 45, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, E.; Okabe, H.; Germine, L.; Wilmer, J.; Esterman, M.; DeGutis, J. Gender differences in sustained attentional control relate to gender inequality across countries. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simpkins, S.D.; Davis-Kean, P.E.; Eccles, J.S. Math and science motivation: A longitudinal examination of the links between choices and beliefs. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 42, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.B. Sense of relatedness boosts engagement, achievement, and well-being: A latent growth model study. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, M.R.; Brackett, M.A.; Rivers, S.E.; White, M.; Salovey, P. Classroom emotional climate, student engagement, and academic achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 104, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shernoff, D.J.; Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Shneider, B.; Shernoff, E.S. Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2003, 18, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.K.F. Applying the self-determination theory (SDT) to explain student engagement in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2022, 54, S14–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Holloway, S.D.; Arendtsz, A.; Bempechat, J.; Li, J. What makes students engaged in learning? A time-use study of within-and between-individual predictors of emotional engagement in low-performing high schools. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Jang, H.; Carrell, D.; Jeon, S.; Barch, J. Enhancing students’ engagement by increasing teachers’ autonomy support. Motiv. Emot. 2004, 28, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carini, R.M.; Kuh, G.D.; Klein, S.P. Student engagement and student learning: Testing the linkages. Res. High. Educ. 2006, 47, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, C.-D. Scaffolding student engagement with written corrective feedback: Transforming feedback sessions into learning affordances. Lang. Teach. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Simons, J.; Lens, W.; Sheldon, K.M.; Deci, E.L. Motivating learning, performance, and persistence: The synergistic effects of intrinsic goal contents and autonomy-supportive contexts. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reilly, D.; Neumann, D.L.; Andrews, G. Sex differences in math and science achievement: A meta-analysis of National Assessment of Educational Progress assessments. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 107, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reinhold, F.; Hofer, S.; Berkowitz, M.; Strohmaier, A.; Scheuerer, S.; Loch, F.; Vogel-Heuser, B.; Reiss, K. The Role of Spatial, Verbal, Numerical, and General Reasoning Abilities in Complex Word Problem Solving for Young Female and Male Adults. Math. Educ. Res. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.A.; Carvalho, P.S.; Ventura, D.R. How to Study the Doppler Effect with Audacity Software. Phys. Educ. 2016, 51, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, S.I.; Reinhold, F.; Koch, M. Students Home Alone—Profiles of Internal and External Conditions Associated with Mathematics Learning from Home. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.T.; Fredricks, J.A.; Ye, F.; Hofkens, T.L.; Linn, J.S. The math and science engagement scales: Scale development, validation, and psychometric properties. Learn. Instr. 2016, 43, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prenzel, M. Mehrdimensionale Bildungsziele Im Mathematikunterricht Und Ihr Zusammenhang Mit Den Basisdimensionen Der Unterrichtsqualität. Multi-Dimens. Educ. Goals Math. Classr. Their Relatsh. Instr. Qual. 2016, 44, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Möller, C.; Spinath, F.M. Are You Swiping, or Just Marking? Exploring the Feasibility of Psychological Testing on Mobile Devices. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 2021, 63, 507–524. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5–12 (BETA). J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Satorra, A.; Bentler, P.M. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika 2001, 66, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, D.; Zhang, D.; He, J.; Bobis, J. The impact of perceived teachers’ autonomy support on students’ mathematics achievement: Evidences based on latent growth curve modelling. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 35, 703–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meece, J.L.; Jones, M.G. Gender differences in motivation and strategy use in science: Are girls rote learners? J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1996, 33, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metallidou, P.; Vlachou, A. Motivational beliefs, cognitive engagement, and achievement in language and math in elementary school children. Int. J. Psychol. 2007, 42, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffing, S.; Wach, F.-S.; Spinath, F.M.; Brünken, R.; Karbach, J. Learning strategies and general cognitive ability as predictors of gender-specific academic achievement. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hofer, S.I.; Stern, E. Underachievement in Physics: When Intelligent Girls Fail. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2016, 51, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, S.I. Studying Gender Bias in Physics Grading: The Role of Teaching Experience and Country. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2015, 37, 2879–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, L. Women in physics: A review. Phys. Teach. 2002, 40, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meece, J.L.; Glienke, B.B.; Burg, S. Gender and motivation. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 44, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taasoobshirazi, G.; Carr, M. Gender differences in science: An expertise perspective. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 20, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, A.C.; Pekrun, R.; Goetz, T. Girls and mathematics—A “hopeless” issue? A control-value approach to gender differences in emotions towards mathematics. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2007, 22, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goetz, T.; Bieg, M.; Lüdtke, O.; Pekrun, R.; Hall, N.C. Do girls really experience more anxiety in mathematics? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 2079–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lohbeck, A.; Grube, D.; Moschner, B. Academic self-concept and causal attributions for success and failure amongst elementary school children. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2017, 25, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, M.M.C.; Kennedy, K.J.; Moore, P.J. Academic attribution of secondary students: Gender, year level and achievement level. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesperance, K.; Hofer, S.; Retelsdorf, J.; Holzberger, D. Reducing Gender Differences in Student Motivational-affective Factors: A Meta-analysis of School-based Interventions. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, bjep.12512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, A.; Stoeger, H. Evaluation of an attributional retraining (modeling technique) to reduce gender differences in chemistry instruction. High Abil. Stud. 2010, 15, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernán, M.; Hernández-Díaz, S.; Robins, J. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology 2004, 15, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smart, R.G. Subject selection bias in psychological research. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 1966, 7, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls (n = 115) | |||||||

| 1. Autonomy support | - | ||||||

| 2. Competence support | 0.45 *** | - | |||||

| 3. Social relatedness | 0.54 *** | 0.46 *** | - | ||||

| 4. Cognitive engagement | 0.45 *** | 0.31 ** | 0.34 *** | - | |||

| 5. Behavioral engagement | 0.38 *** | 0.25 ** | 0.32 *** | 0.75 *** | - | ||

| 6. Math performance | 0.18 | −0.03 | 0.15 | 0.51 *** | 0.33 *** | - | |

| 7. Sustained attention a | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.28 * | - |

| Boys (n = 106) | |||||||

| 1. Autonomy support | - | ||||||

| 2. Competence support | 0.53 ** | - | |||||

| 3. Social relatedness | 0.65 ** | 0.58 ** | - | ||||

| 4. Cognitive engagement | 0.47 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.43 ** | - | |||

| 5. Behavioral engagement | 0.48 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.76 ** | - | ||

| 6. Math performance | 0.39 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.56 ** | - | |

| 7. Sustained attention a | 0.30 * | 0.20 | 0.48 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.70 ** | - |

| Variables | Girls (n = 115) | Boys (n = 106) | t | 95% CI [LL; UL] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Autonomy support | 1–4 | 2.80 | 0.46 | 2.83 | 0.53 | −0.47 | [−0.16; 0.10] |

| Competence support | 1–4 | 2.97 | 0.50 | 3.14 | 0.60 | −2.25 * | [−0.31; −0.02] |

| Social relatedness | 1–4 | 3.04 | 0.55 | 3.03 | 0.66 | 0.10 | [−0.15; 0.17] |

| Cognitive engagement | 1–4 | 3.15 | 0.49 | 3.02 | 0.53 | 1.90 | [−0.01; 0.27] |

| Behavioral engagement | 1–4 | 3.08 | 0.50 | 2.94 | 0.53 | 2.09 * | [0.01; 0.28] |

| Math performance | 0–12 | 8.75 | 3.34 | 8.53 | 3.80 | 0.46 | [−0.73; 1.17] |

| Sustained attention a | - | 12.45 | 23.89 | 4.07 | 28.53 | 1.94 | [−0.17; 16.94] |

| Main Model | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls (n = 115) | Boys (n = 106) | Gender Differences | ||||||||

| Model Path | β | SE | z | p | β | SE | z | p | Δchi2 | p |

| Aut. sup. → Cog. eng. | 0.37 | 0.11 | 3.34 | <0.001 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 2.77 | 0.006 | 0.14 | 0.713 |

| Comp. sup. → Cog. eng. | 0.1 | 0.09 | 1.13 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.63 | 0.53 | - | - |

| Soc. relat. → Cog. eng. | 0.09 | 0.09 | 1.02 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 1.46 | 0.143 | - | - |

| Aut. sup. → Beh. eng. | 0.29 | 0.12 | 2.34 | 0.019 | 0.26 | 0.1 | 2.5 | 0.013 | 0.03 | 0.866 |

| Comp. sup. → Beh. eng. | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.74 | 0.461 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.872 | - | - |

| Soc. relat. → Beh. eng. | 0.13 | 0.12 | 1.12 | 0.262 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 3.07 | 0.002 | 0.72 | 0.395 |

| Cog. eng. → Math | 4.52 | 0.63 | 7.22 | <0.001 | 1.77 | 0.65 | 2.74 | 0.006 | 4.49 | 0.034 |

| Beh. eng. → Math | −0.85 | 0.57 | −1.49 | 0.135 | 1.62 | 0.64 | 2.53 | 0.011 | 4.23 | 0.04 |

| Aut. sup. → Math | −0.11 | 0.79 | −0.13 | 0.893 | −0.64 | 0.73 | −0.88 | 0.38 | - | - |

| Comp. sup. → Math | −1.50 | 0.6 | −2.49 | 0.013 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.83 | 0.405 | 5.65 | 0.017 |

| Soc. relat. → Math | 0.43 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.539 | 1.85 | 0.68 | 2.71 | 0.007 | 2.11 | 0.146 |

| Aut. sup. → Cog. eng. → Math | 1.67 | 0.57 | 2.94 | 0.003 | 0.55 | 0.29 | 1.92 | 0.055 | 4.99 | 0.083 |

| Comp. sup. → Cog. eng. → Math | 0.44 | 0.41 | 1.09 | 0.277 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.63 | 0.527 | - | - |

| Soc. relat. → Cog. eng. → Math | 0.42 | 0.41 | 1.02 | 0.305 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 1.2 | 0.232 | - | - |

| Aut. sup. → Beh. eng. → Math | −0.24 | 0.17 | −1.43 | 0.154 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 1.73 | 0.084 | - | - |

| Comp. sup. → Beh. eng. → Math | −0.06 | 0.08 | −0.69 | 0.49 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.872 | - | - |

| Soc. relat. → Beh. eng. → Math | −0.11 | 0.14 | −0.79 | 0.429 | 0.42 | 0.22 | 1.88 | 0.059 | - | - |

| R2 | ||||||||||

| Cognitive engagement | 0.23 | 0.25 | ||||||||

| Behavioral engagement | 0.16 | 0.29 | ||||||||

| Math performance | 0.37 | 0.4 | ||||||||

| Extended Model (Reduced Sample) | Main Model (Reduced Sample) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls (n = 77) | Boys (n = 72) | Gender Diff. | Girls (n = 77) | Boys (n = 72) | ||||||||||||||

| Model Path | β | SE | z | p | β | SE | z | p | Δchi2 | p | β | SE | z | p | β | SE | z | p |

| Aut. sup. → Cog. eng. | 0.32 | 0.12 | 2.61 | 0.009 | 0.36 | 0.11 | 3.32 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.774 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 2.56 | 0.010 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 3.25 | 0.001 |

| Comp. sup. → Cog. eng. | 0.13 | 0.09 | 1.45 | 0.146 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 1.22 | 0.223 | - | - | 0.13 | 0.09 | 1.37 | 0.169 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.67 | 0.500 |

| Soc. relat. → Cog. eng. | 0.14 | 0.09 | 1.59 | 0.112 | −0.07 | 0.14 | −0.49 | 0.623 | - | - | 0.16 | 0.09 | 1.73 | 0.083 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.89 | 0.376 |

| Sust. attent. → Cog. eng. | 0.003 | 0.002 | 1.60 | 0.109 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 3.95 | <0.001 | 2.84 | 0.092 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Aut. sup. → Beh. eng. | 0.18 | 0.12 | 1.49 | 0.136 | 0.36 | 0.10 | 3.52 | <0.001 | 1.27 | 0.260 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 1.48 | 0.140 | 0.37 | 0.11 | 3.39 | 0.001 |

| Comp. sup. → Beh. eng. | 0.11 | 0.09 | 1.13 | 0.258 | −0.002 | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.986 | - | - | 0.10 | 0.09 | 1.05 | 0.294 | −0.06 | 0.13 | −0.46 | 0.645 |

| Soc. relat. → Beh. eng. | 0.23 | 0.10 | 2.24 | 0.025 | 0.06 | 0.11 | .54 | 0.591 | 1.05 | 0.306 | 0.24 | 0.11 | 2.24 | 0.025 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 1.92 | 0.055 |

| Sust. attent. → Beh. eng. | 0.003 | 0.002 | 1.50 | 0.134 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 2.81 | 0.005 | 1.64 | 0.200 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cog. eng. → Math | 2.96 | 0.76 | 3.92 | <0.001 | −0.71 | 0.57 | −1.26 | 0.206 | 9.37 | 0.002 | 3.18 | 0.81 | 3.94 | <0.001 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.518 |

| Beh. eng. → Math | −1.20 | 0.83 | −1.44 | 0.149 | 1.81 | 0.65 | 2.80 | 0.005 | 5.25 | 0.022 | −1.08 | 0.87 | −1.24 | 0.214 | 2.28 | 0.76 | 3.00 | 0.003 |

| Aut. sup. → Math | 0.09 | 0.74 | 0.12 | 0.904 | −0.33 | 0.74 | −0.45 | 0.655 | - | - | 0.03 | 0.77 | 0.04 | 0.972 | −0.86 | 0.92 | −0.93 | 0.351 |

| Comp. sup. → Math | −1.58 | 0.71 | −2.23 | 0.026 | 0.99 | 0.60 | 1.67 | 0.096 | 7.89 | 0.005 | −1.69 | 0.72 | −2.34 | 0.019 | 0.35 | 0.73 | 0.48 | 0.630 |

| Soc. relat. → Math | 1.22 | 0.56 | 2.18 | 0.029 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 1.49 | 0.136 | 0.06 | 0.801 | 1.28 | 0.56 | 2.30 | 0.022 | 2.41 | 0.72 | 3.36 | 0.001 |

| Sust. attent. → Math | 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.95 | 0.051 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 4.19 | <0.001 | 4.35 | 0.037 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Aut. sup. → Cog. eng. → Math | 0.94 | 0.44 | 2.12 | 0.034 | −0.26 | 0.21 | −1.23 | 0.220 | 9.38 | 0.009 | 1.01 | 0.47 | 2.14 | 0.032 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.63 | 0.530 |

| Comp. sup. → Cog. eng. → Math | 0.39 | 0.28 | 1.40 | 0.162 | −0.10 | 0.11 | −0.87 | 0.386 | - | - | 0.40 | 0.31 | 1.29 | 0.197 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.53 | 0.598 |

| Soc. relat. → Cog. eng. → Math | 0.42 | 0.30 | 1.43 | 0.154 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.46 | 0.642 | - | - | 0.50 | 0.33 | 1.52 | 0.129 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.48 | 0.633 |

| Sust. attent. → Cog. eng. → Math | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.45 | 0.148 | −0.01 | 0.005 | −1.18 | 0.237 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Aut. sup. → Beh. eng. → Math | −0.21 | 0.21 | −1.00 | 0.317 | .66 | 0.32 | 2.06 | 0.040 | 6.91 | 0.032 | −0.19 | 0.21 | −0.92 | 0.359 | 0.85 | 0.43 | 1.98 | 0.048 |

| Comp. sup. → Beh. eng. → Math | −0.13 | 0.15 | −0.83 | 0.408 | −0.004 | 0.24 | −0.02 | 0.986 | - | - | −0.11 | 0.14 | −0.76 | 0.446 | −0.13 | 0.30 | −0.44 | 0.663 |

| Soc. relat. → Beh. eng. → Math | −0.27 | 0.22 | −1.24 | 0.214 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.54 | 0.591 | - | - | −0.26 | 0.23 | −1.11 | 0.267 | 0.50 | 0.32 | 1.57 | 0.117 |

| Sust. attent. → Beh. eng. → Math | −0.003 | 0.003 | −1.14 | 0.254 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.79 | 0.073 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| R2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cognitive engagement | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.30 | 0.30 | ||||||||||||||

| Behavioral engagement | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.26 | 0.30 | ||||||||||||||

| Math performance | 0.33 | 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.43 | ||||||||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hofer, S.I.; Reinhold, F.; Hulaj, D.; Koch, M.; Heine, J.-H. What Matters for Boys Does Not Necessarily Matter for Girls: Gender-Specific Relations between Perceived Self-Determination, Engagement, and Performance in School Mathematics. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12110775

Hofer SI, Reinhold F, Hulaj D, Koch M, Heine J-H. What Matters for Boys Does Not Necessarily Matter for Girls: Gender-Specific Relations between Perceived Self-Determination, Engagement, and Performance in School Mathematics. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(11):775. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12110775

Chicago/Turabian StyleHofer, Sarah Isabelle, Frank Reinhold, Dilan Hulaj, Marco Koch, and Jörg-Henrik Heine. 2022. "What Matters for Boys Does Not Necessarily Matter for Girls: Gender-Specific Relations between Perceived Self-Determination, Engagement, and Performance in School Mathematics" Education Sciences 12, no. 11: 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12110775

APA StyleHofer, S. I., Reinhold, F., Hulaj, D., Koch, M., & Heine, J.-H. (2022). What Matters for Boys Does Not Necessarily Matter for Girls: Gender-Specific Relations between Perceived Self-Determination, Engagement, and Performance in School Mathematics. Education Sciences, 12(11), 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12110775