Mixed Methods in Analysis of Aggressiveness and Attractiveness: Understanding PE Class Social Networks with Content Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Interpersonal Attractiveness

1.2. Verbal Aggressiveness

1.3. Aim of the Study

2. Methodology of the Study

2.1. Analysis of Social Networks

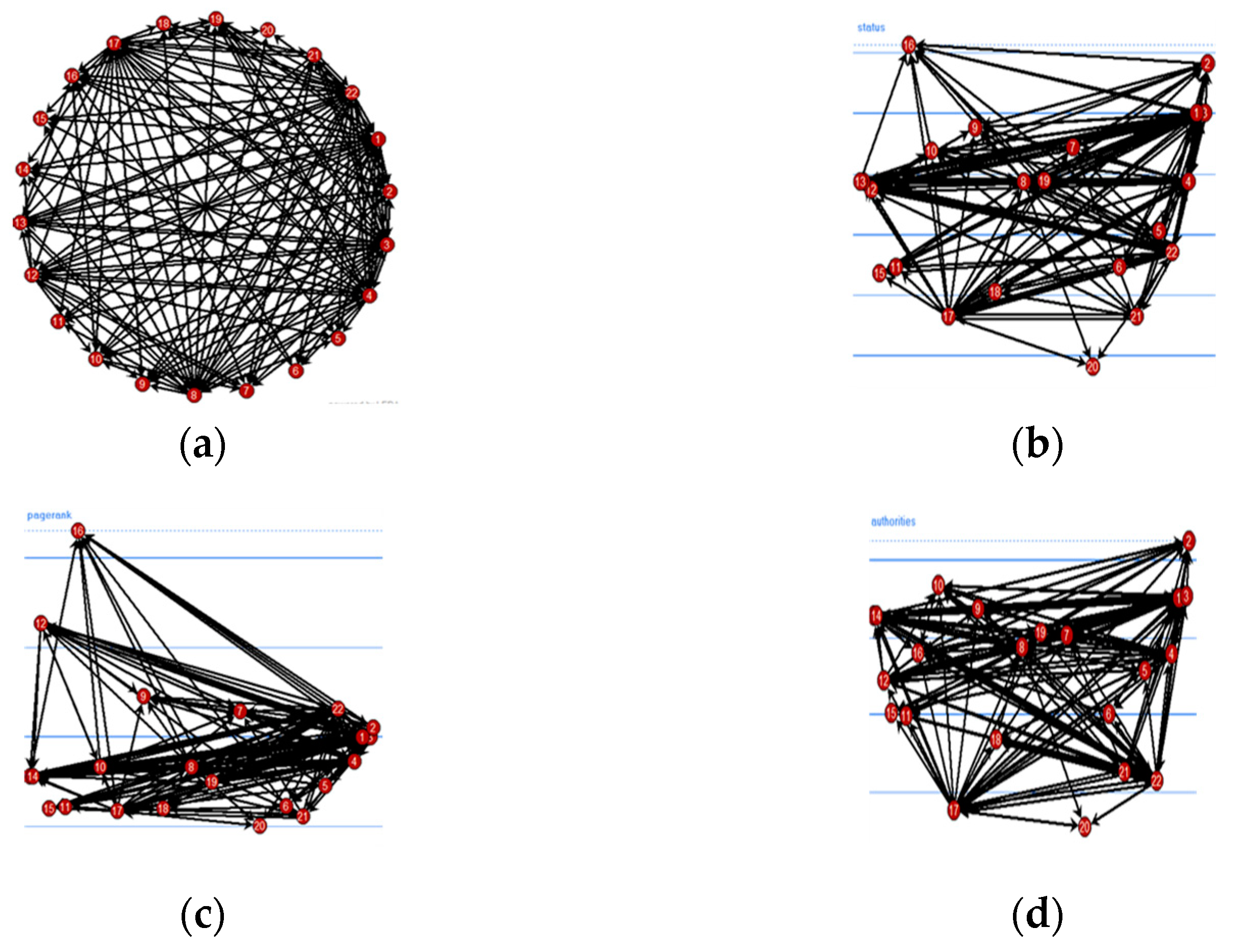

- (a)

- In- and Out-degree (occasional influence) concerns direct contact: the in-going means influence one receives from the other nodes and the influence that one creates towards the other nodes having out-going contact to them;

- (b)

- Katz status (cumulative influence) means the influence exerted by a person through a successive process: the number and size of the chain-contacts leading from each node to the next one successively. Thereby, there is a deeper, long-chain relationship rather than an occasional one;

- (c)

- Pagerank (distributional influence) is similar to Katz status but narrows the edges because it is based on the transferred value from one node to another: it counts the number of nodes that come into contact with each other and not the length of chain-relationships;

- (d)

- Authority (special competitiveness or dominant position) shows the nodes that attracts the most links from the other nodes, among those that intensively seek to maintain relationships. In this case, it reveals a clear tendency to become a target. For example, high authority in case of attractiveness characterizes a student who has attracted links from many other students who are intensively looking for attractive students. Their formulas are easily accessible on the web (https://visone.ethz.ch/wiki/images/6/67/VisoneTutorial-archeology.pdf, accessed on 25 June 2021). The above indicators are centrality analysis indicators. Centrality indicates the number of connections each node has in their network. Thus, it represents the individual characteristics of the nodes and consists of an expression of the social structures (relationships between the top and bottom nodes of the hierarchies). Centrality indicates the importance of each node in the network and the extent of potential change in the network in case of a particular node’s withdrawal.

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Data Collection: Procedure

2.1.3. Research Tools

2.1.4. Data Analysis

2.2. Analysis of Qualitative Approach

2.2.1. Qualitative Data Collection

2.2.2. Data Analysis of Qualitative Data

3. Results

3.1. Social Network Analysis

3.2. Statistical Analysis

3.3. Content Analysis of Open-Ended Questions

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berscheid, E.; Reis, H.T. Attraction and close relationships. In Handbook of Social Psychology, 4th ed.; Gilbert, D.T., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 193–281. [Google Scholar]

- McCroskey, J.C.; Hamilton, P.R.; Weiner, A.N. The effect of interaction behavior on source credibility, homophily, and interpersonal attraction. Hum. Commun. Res. 1974, 1, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berscheid, E.; Walster, E.H. Interpersonal Attraction; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, R.J.; Roberts, B.W. A socioanalytic perspective on person-environment. In Person-Environment Psychology: New Directions and Perspectives, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.P.; Bailey, J.M.; Kenrick, D.T.; Linsenmeier, J.A. The necessities and luxuries of mate preferences: Testing the tradeoffs. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, B. Friendship formation. In Handbook of Relationship Initiation; Sprecher, A.W.S., Harvey, J., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, K.; Holderness, N.; Riggs, M. Friendship chemistry: An examination of underlying factors. Soc. Sci. J. 2015, 52, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Singh, R.; Jen Ho, L.; Tan, H.L.; Bell, P.A. Attitudes, personal evaluations, cognitive evaluation and interpersonal attraction: On the direct, indirect and reverse-causal effects. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 46, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunnafrank, M.; Ramirez, A., Jr. At first sight: Persistent relational effects of get-acquainted conversations. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2004, 21, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zalk, M.; Denissen, J. Idiosyncratic versus social consensus approaches to personality: Self-view, perceived, and peer-view similarity. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winch, R.F.; Ktsanes, T.; Ktsanes, V. The theory of complementary needs in mate-selection: An analytic and descriptive study. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1954, 19, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, A.; Aron, E.N. Handbook of Personal Relationships: Theory, Research and Intervention, Self-Expansion Motivation and Including Other in the Self; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 251–270. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin, I.E. Relationship between Affective Learning, Instructor Attractiveness and Instructor Evaluation in Videoconference-Based Distance Education Courses. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol.-TOJET 2012, 11, 247–252. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ989274.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2020).

- Myers, S.A.; Horan, S.M.; Kennedy-Lightsey, C.D.; Madlock, P.E.; Sidelinger, R.J.; Byrnes, K.; Frisby, B.; Mansson, D.H. The relationship between college students’ self-reports of class participation and perceived instructor impressions. Commun. Res. Rep. 2009, 26, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrmpas, I.; Bekiari, A. The Relationship between Perceived Physical Education Teacher’s Verbal Aggressiveness and Argumentativeness with Students’ Interpersonal Attraction. Inq. Sport Phys. Educ. 2015, 13, 21–32. Available online: http://research.pe.uth.gr/emag/index.php/inquiries/article/view/160 (accessed on 20 February 2017).

- Infante, D.A.; Rancer, A.S. Argumentativeness and verbal aggressiveness: A review of recent theory and research. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 1996, 19, 319–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliligka, S.; Bekiari, A.; Syrmpas, I. Verbal aggressiveness and argumentativeness in physical education: Perceptions of teachers and students in qualitative and quantitative exploration. Psychology 2017, 8, 1693–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avtgis, T.A.; Rancer, A.S. Arguments, Aggression, and Conflict: New Directions in Theory and Research; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bekiari, A.; Hasanagas, N. Suggesting indicators of superficiality and purity in verbal aggressiveness: An application in adult education class networks of prison inmates. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 4, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, S.A.; Brann, M.; Martin, M.M. Identifying the content and topics of instructor use of verbally aggressive messages. Commun. Res. Rep. 2013, 30, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancer, A.S.; Avtgis, T.A. Argumentative and Aggressive Communication: Theory, Research, and Application; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bekiari, A.; Hasanagas, N. Verbal aggressiveness exploration through complete social network analysis: Using physical education students’ class as an illustration. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2015, 3, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aloia, L.S.; Solomon, D.H. Emotions Associated with Verbal Aggression Expression and Suppression. West. J. Commun. 2015, 80, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, D.A. Teaching students to understand and control verbal aggression. Commun. Educ. 1995, 44, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samp, J.A. Communicating Interpersonal Conflict in Close Relationships: Contexts, Challenges, and Opportunities; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bekiari, A.; Spyropoulou, S. Exploration of Verbal Aggressiveness and Interpersonal Attraction through Social Network Analysis: Using University Physical Education Class as an Illustration. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 4, 145–155. Available online: http://www.scirp.org/journal/PaperInformation.aspx?PaperID=67520&#abstract (accessed on 1 May 2022). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bekiari, A.; Kokaridas, D.; Sakellariou, K. Associations of students’ self-reports of their teachers’ verbal aggression, intrinsic motivation, and perceptions of reasons for discipline in Greek physical education classes. Psychol. Rep. 2006, 98, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekiari, A. Perceptions of instructor’s verbal aggressiveness and physical education students’ affective learning. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2012, 115, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekiari, A.; Patsiaouras, A.; Kokaridas, D.; Sakellariou, K. Verbal aggressiveness and state anxiety of volleyball players and coaches. Psychol. Rep. 2006, 99, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infante, D.A.; Wigley, C.J., III. Verbal aggressiveness: An interpersonal model and measure. Commun. Monogr. 1986, 53, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brann, M.; Edwards, C.; Myers, S.A. Perceived instructor credibility and teaching philosophy. Commun. Res. Rep. 2005, 22, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekiari, A.; Petanidis, D. Exploring teachers’ verbal aggressiveness through interpersonal attraction and students’ intrinsic motivation. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 4, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moolenaar, N.M.; Daly, A.J.; Sleegers, P.J. Occupying the principal position: Examining relationships between transformational leadership, social network position, and schools’ innovative climate. Educ. Adm. Q. 2010, 46, 623–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Daly, A.; Liou, Y.H. Improving trust, improving schools: Findings from a social network analysis of 43 primary schools in England. J. Prof. Cap. Community 2016, 1, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, A.J.; Moolenaar, N.M.; Bolivar, J.M.; Burke, P. Relationships in reform: The role of teachers′ social networks. J. Educ. Adm. 2010, 48, 359–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Theocharis, D.; Bekiari, A. Dynamic Analysis of Verbal Aggressiveness Networks in School. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 6, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Theoharis, D.; Bekiari, A.; Koustelios, A. Exploration of Determinants of Verbal Aggressiveness and Leadership through Network Analysis and Conventional Statistics. Using School Class as an Illustration. Sociol. Mind 2016, 7, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruggiero, T.E.; Lattin, K.S. Intercollegiate female coaches′ use of verbally aggressive communication toward African American female athletes. Howard J. Commun. 2008, 19, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.H.; Grange, P. Athlete-to-athlete verbal aggression: A case study of interpersonal communication among elite Australian footballers. Int. J. Sport Commun. 2009, 2, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice and Using Software; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. Social network analysis. Sociology 1988, 22, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. Social Network Analysis: A Handbook, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Heidler, R.; Gamper, M.; Herz, A.; Eßer, F. Relationship patterns in the 19th century: The friendship network in a German boys’ school class from 1880 to 1881 revisited. Soc. Netw. 2014, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popitz, H. Phänomene der Macht; Mohr Siebeck: Tübingen, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bekiari, A.; S. Deliligka, A.; Vasilou, A.; Hasanagas, N. Socioeducational Determinants of “Bad Behaviour” of Students: A Comparative Analysis among Primary, Secondary, and High School. Int. J. Learn. Divers. Identities 2019, 26, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friborg, O.; Rosenvinge, J.H. A comparison of open-ended and closed questions in the prediction of mental health. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 1397–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popping, R. Analyzing open-ended questions by means of text analysis procedures. Bull. Sociol. Methodol./Bull. Méthodol. Sociol. 2015, 128, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meitinger, K.; Behr, D.; Braun, M. Using apples and oranges to judge quality? Selection of appropriate cross-national indicators of response quality in open-ended questions. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2019, 39, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl, E.; Jacoby, A.; Thomas, L.; Soutter, J.; Bamford, C.; Steen, N.; Thomas, R.; Harvey, E.; Garratt, A.; Bond, J. Design and use of questionnaires: A review of best practice applicable to surveys of health service staff and patients. Health Technol. Assess. 2001, 5, 1–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Given, L.M. The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Given, L.M., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. What counts as qualitative research? Some cautionary comments. Qual. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 9, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspers, P.; Corte, U. What is qualitative in qualitative research. Qual. Sociol. 2019, 42, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodwin, J.; Horowitz, R. Introduction: The methodological strengths and dilemmas of qualitative sociology. Qual. Sociol. 2002, 25, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Neuendorf, K. The Content Analysis Guidebook; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Radiker, S.; Kuckartz, U. Focused Analysis of Qualitative Interviews with MAXQDA: Step by Step; MAXQDA Press: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, M.; Ann, S. Methodological pluralism and the possibilities and limits of interviewing. Qual. Sociol. 2014, 37, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, J.L.; Galvan, J.; Villasenor, J.; Henkin, J. You’ve been on my mind ever since”: A content analysis of expressions of interpersonal attraction in Craigslist. Org′s Missed Connections posts. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezlek, J.B.; Schütz, A.; Schröder-Abé, M.; Smith, C.V. A cross-cultural study of relationships between daily social interaction and the five-factor model of personality. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 79, 811–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lösch, T.; Rentzsch, K. Linking Personality with Interpersonal Perception in the Classroom: Distinct Associations with the Social and Academic Sides of Popularity. J. Res. Personal. 2018, 75, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veelen, R.; Eisenbeiss, K.K.; Otten, S. Newcomers to social categories: Longitudinal predictors and consequences of ingroup identification. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 42, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, J.; Brauer, J.R.; Ellonen, N. Beauty is in the eye of the offender: Physical attractiveness and adolescent victimization. J. Crim. Justice 2020, 66, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, M.; Henttonen, P.; Ravaja, N. The role of personality in dyadic interaction: A psychophysiological study. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2016, 109, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.G.; McCroskey, J.C. The association of perceived communication apprehension, shyness, and verbal aggression with perceptions of source credibility and affect in organizational and interpersonal contexts. Commun. Q. 2003, 51, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lybarger, J.E.; Rancer, A.S.; Lin, Y. Superior–Subordinate Communication in the Workplace: Verbal Aggression, Nonverbal Immediacy, and Their Joint Effects on Perceived Superior Credibility. Commun. Res. Rep. 2017, 34, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekiari, A.; Nikolaidou, Z.A.; Hasanagas, N. Typology of Motivation and Aggression on the Basis of Social Network Variables: Examples of Complementary and Nested Behavioral Types through Conventional Statistics. Soc. Netw. 2017, 6, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vasilou, A.; Bekiari, A.; Hasanagas, N. Aggressiveness networks at school classes: Dynamic analysis and comparison of structures. Int. J. Interdiscip. Educ. Stud. 2020, 15, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekiari, A.; Balla, K. Instructors and Students Relations: Argumentativeness, Leadership and Goal Orientations. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 5, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muñoz Reyes, J.A.; Guerra, R.; Polo, P.; Cavieres, E.; Pita, M.; Turiégano, E. Using an evolutionary perspective to understand the relationship between physical aggression and academic performance in late adolescents. J. Sch. Violence 2019, 18, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuzer, Y.; Karataş, Z. Associations between popularity and aggression in Turkish early adolescents. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Network Variables | Argumentativeness | Social Power | Verbal Aggressiveness | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Network Variables | Disagreement | Agreement | Weakness | Advice_Lessons | Advice_Personal | Sympathy | Hurt | Irony | Rudeness | Threat |

| gender | −0.076 | 0.102 | −0.088 | 0.269 | 0.142 | −0.046 | −0.033 | 0.008 | −0.04 | −0.224 |

| 0.487 | 0.35 | 0.415 | 0.012 | 0.188 | 0.674 | 0.763 | 0.938 | 0.716 | 0.037 | |

| height | −0.029 | −0.146 | −0.013 | −0.161 | −0.159 | −0.001 | 0.2 | 0.074 | 0.219 | 0.392 |

| 0.808 | 0.219 | 0.91 | 0.173 | 0.179 | 0.992 | 0.09 | 0.535 | 0.062 | 0.001 | |

| weight | 0.011 | −0.316 | 0.066 | −0.242 | −0.251 | −0.171 | 0.203 | 0.093 | 0.153 | 0.099 |

| 0.928 | 0.008 | 0.589 | 0.043 | 0.036 | 0.158 | 0.091 | 0.441 | 0.207 | 0.414 | |

| place of living(town–village) | −0.208 | −0.001 | 0.157 | −0.084 | −0.15 | −0.069 | −0.287 | −0.116 | −0.334 | −0.167 |

| 0.062 | 0.996 | 0.162 | 0.457 | 0.18 | 0.539 | 0.009 | 0.304 | 0.002 | 0.137 | |

| financial_status_family | 0 | 0.006 | −0.047 | −0.235 | −0.242 | −0.049 | 0.029 | −0.114 | 0.045 | −0.056 |

| 0.999 | 0.958 | 0.701 | 0.05 | 0.044 | 0.685 | 0.814 | 0.349 | 0.711 | 0.647 | |

| general_grade | −0.177 | 0.37 | −0.324 | 0.713 | 0.341 | 0.175 | 0.011 | −0.121 | −0.037 | 0.068 |

| 0.14 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0 | 0.004 | 0.144 | 0.927 | 0.314 | 0.762 | 0.572 | |

| travel_abroad_last_5_years | −0.06 | −0.075 | −0.103 | −0.111 | −0.413 | −0.024 | 0.003 | −0.051 | −0.091 | −0.114 |

| 0.595 | 0.505 | 0.358 | 0.322 | 0 | 0.833 | 0.976 | 0.65 | 0.418 | 0.311 | |

| surf_the_net_entertainment | 0.131 | −0.087 | −0.073 | 0.079 | 0.106 | 0.035 | 0.252 | −0.012 | 0.152 | −0.034 |

| 0.249 | 0.446 | 0.524 | 0.491 | 0.353 | 0.76 | 0.025 | 0.917 | 0.182 | 0.769 | |

| surf_the_net_hours | 0.252 | 0.053 | 0.068 | −0.143 | −0.062 | −0.078 | 0.057 | 0.108 | 0.202 | 0.096 |

| 0.033 | 0.661 | 0.569 | 0.231 | 0.602 | 0.517 | 0.636 | 0.366 | 0.088 | 0.421 | |

| be_inspired_positively_lessons | −0.15 | 0.07 | 0.034 | −0.093 | 0.035 | −0.229 | 0.018 | −0.067 | −0.025 | −0.006 |

| 0.191 | 0.543 | 0.767 | 0.42 | 0.763 | 0.043 | 0.875 | 0.56 | 0.83 | 0.96 | |

| inspire_positively_lessons | −0.295 | 0.212 | −0.07 | 0.179 | 0.061 | 0.043 | −0.133 | −0.044 | −0.121 | 0.046 |

| 0.01 | 0.065 | 0.549 | 0.122 | 0.601 | 0.713 | 0.254 | 0.704 | 0.296 | 0.694 | |

| inspire_positively_appearance | −0.032 | 0.12 | −0.272 | 0.238 | −0.01 | 0.124 | 0.095 | −0.07 | 0.065 | −0.001 |

| 0.784 | 0.303 | 0.018 | 0.04 | 0.929 | 0.29 | 0.416 | 0.55 | 0.581 | 0.995 | |

| distinction at school | −0.128 | 0.239 | −0.09 | 0.3 | 0.202 | 0.024 | 0.037 | 0.059 | 0.025 | 0.113 |

| 0.256 | 0.032 | 0.426 | 0.006 | 0.071 | 0.833 | 0.743 | 0.603 | 0.825 | 0.314 | |

| distinction_professional | 0.019 | 0.225 | −0.151 | 0.293 | 0.208 | 0.076 | −0.039 | 0.072 | −0.083 | 0.18 |

| 0.864 | 0.045 | 0.18 | 0.008 | 0.064 | 0.501 | 0.734 | 0.527 | 0.466 | 0.11 | |

| scientific distinction | −0.149 | 0.133 | −0.219 | 0.348 | −0.043 | 0.005 | −0.073 | 0.105 | 0.028 | 0.067 |

| 0.187 | 0.241 | 0.051 | 0.002 | 0.705 | 0.967 | 0.521 | 0.353 | 0.803 | 0.553 | |

| distinction in life | 0.151 | 0.237 | −0.595 | 0.307 | 0.006 | 0.29 | 0.235 | 0.214 | 0.104 | 0.062 |

| 0.301 | 0.101 | 0 | 0.032 | 0.966 | 0.043 | 0.104 | 0.139 | 0.477 | 0.671 | |

| opt for friends_knowledge | 0.043 | −0.326 | 0.143 | −0.143 | −0.215 | −0.059 | 0.141 | 0.07 | 0.074 | −0.062 |

| 0.705 | 0.003 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.057 | 0.608 | 0.215 | 0.542 | 0.519 | 0.587 | |

| opt for smart friends | −0.238 | 0.088 | −0.054 | 0.095 | 0.151 | 0.102 | −0.119 | −0.094 | −0.057 | −0.017 |

| 0.035 | 0.44 | 0.636 | 0.406 | 0.185 | 0.372 | 0.296 | 0.409 | 0.619 | 0.883 | |

| opt for attractive friends | 0.061 | −0.157 | 0.048 | 0.057 | −0.134 | −0.235 | −0.033 | −0.056 | 0.114 | 0.098 |

| 0.596 | 0.17 | 0.676 | 0.621 | 0.243 | 0.038 | 0.777 | 0.627 | 0.319 | 0.392 | |

| Network Variables | Scientific Attractiveness | Social Attractiveness | Physical Attractiveness | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Network Variables | Help_Homework | Help_Homework_ Others | Friendly_to_ You | Friendly_to_ Others | Attractive_to_ You_ | Attractive_to_ Others_ |

| gender | 0.329 | 0.254 | −0.047 | 0.099 | 0.197 | 0.129 |

| 0.002 | 0.018 | 0.668 | 0.361 | 0.068 | 0.233 | |

| height | −0.167 | −0.284 | 0.14 | −0.038 | −0.029 | −0.058 |

| 0.157 | 0.015 | 0.236 | 0.749 | 0.805 | 0.626 | |

| weight | −0.309 | −0.463 | 0.014 | −0.093 | −0.228 | −0.194 |

| 0.009 | 0 | 0.907 | 0.444 | 0.057 | 0.108 | |

| financial_status_family | −0.198 | −0.233 | −0.095 | −0.075 | −0.285 | −0.246 |

| 0.1 | 0.052 | 0.433 | 0.539 | 0.017 | 0.041 | |

| general_grade | 0.725 | 0.411 | 0.243 | 0.453 | 0.032 | 0.047 |

| 0 | 0 | 0.041 | 0 | 0.791 | 0.696 | |

| travel_abroad_last_5_years | −0.12 | −0.13 | −0.142 | −0.266 | −0.216 | −0.165 |

| 0.285 | 0.249 | 0.208 | 0.016 | 0.053 | 0.14 | |

| surf_the_net_hours | −0.256 | −0.163 | 0.004 | −0.093 | 0.225 | 0.236 |

| 0.03 | 0.171 | 0.974 | 0.435 | 0.058 | 0.046 | |

| inspire_positivelt_behaviour | 0.233 | 0.123 | 0.033 | −0.03 | −0.055 | −0.019 |

| 0.04 | 0.285 | 0.777 | 0.792 | 0.634 | 0.868 | |

| inspire_positively_lessons | 0.276 | 0.264 | 0.119 | 0.17 | 0.029 | 0.051 |

| 0.016 | 0.021 | 0.308 | 0.143 | 0.806 | 0.661 | |

| inspire_positively_appearance | 0.277 | 0.176 | −0.04 | 0.017 | 0.193 | 0.182 |

| 0.016 | 0.131 | 0.732 | 0.883 | 0.097 | 0.119 | |

| distinction at school | 0.418 | 0.14 | 0.156 | 0.246 | −0.105 | −0.015 |

| 0 | 0.212 | 0.165 | 0.027 | 0.353 | 0.893 | |

| distinction _professional | 0.328 | 0.025 | 0.108 | 0.257 | −0.103 | −0.024 |

| 0.003 | 0.825 | 0.338 | 0.021 | 0.364 | 0.832 | |

| scientific distinction | 0.365 | 0.229 | 0.094 | 0.118 | −0.044 | −0.081 |

| 0.001 | 0.041 | 0.409 | 0.297 | 0.701 | 0.475 | |

| distinction in life | 0.344 | 0.265 | 0.003 | −0.009 | 0.253 | 0.236 |

| 0.015 | 0.065 | 0.985 | 0.952 | 0.08 | 0.103 | |

| opt for friends with knowledge | −0.202 | −0.258 | −0.215 | −0.261 | −0.101 | −0.13 |

| 0.074 | 0.022 | 0.057 | 0.02 | 0.376 | 0.252 | |

| opt for smart friends | 0.093 | 0.122 | 0.251 | 0.109 | 0.045 | 0.018 |

| 0.414 | 0.283 | 0.026 | 0.338 | 0.695 | 0.875 | |

| opt for attractive friends | −0.047 | −0.203 | −0.13 | −0.178 | −0.257 | −0.134 |

| 0.68 | 0.074 | 0.256 | 0.118 | 0.023 | 0.241 | |

| Argumentativeness | Social Power | Verbal Aggressiveness | Scientific Attractiveness | Social Attractiveness | Physical Attractiveness | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disagreement | Agreement | Weakness | Advice_ Lessons | Advice_ Personal | Sympathy | Hurt | Irony | Rudeness | Threat | Help_ Homework | Help_Homework_ Others | Friendly_ to_You | Friendly_ to_Others | Attractive_ to_You_ | Attractive_ to_Others | |

| disagreement | 1 | −0.342 | 0.136 | −0.206 | −0.098 | −0.215 | 0.416 | 0.311 | 0.419 | 0.172 | −0.313 | −0.235 | −0.375 | −0.246 | 0.050 | −0.053 |

| - | 0.001 | 0.208 | 0.056 | 0.369 | 0.045 | - | 0.003 | - | 0.112 | 0.003 | 0.028 | - | 0.022 | 0.648 | 0.629 | |

| agreement | −0.342 | 1 | −0.355 | 0.345 | 0.494 | 0.536 | −0.173 | −0.126 | −0.106 | 0.041 | 0.519 | 0.298 | 0.614 | 0.639 | 0.388 | 0.328 |

| 0.001 | - | 0.001 | 0.001 | - | - | 0.108 | 0.246 | 0.330 | 0.708 | - | 0.005 | - | - | - | 0.002 | |

| weakness | 0.136 | −0.355 | 1 | −0.430 | −0.038 | −0.494 | −0.029 | 0.149 | 0.008 | 0.036 | −0.474 | −0.191 | −0.180 | −0.173 | −0.215 | −0.142 |

| 0.208 | 0.001 | - | - | 0.723 | - | 0.788 | 0.169 | 0.945 | 0.741 | - | 0.077 | 0.095 | 0.108 | 0.046 | 0.189 | |

| advice_lessons | −0.206 | 0.345 | −0.430 | 1 | 0.359 | 0.328 | −0.099 | −0.184 | −0.069 | −0.065 | 0.810 | 0.495 | 0.367 | 0.326 | 0.208 | 0.133 |

| 0.056 | 0.001 | 0.000 | - | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.361 | 0.087 | 0.525 | 0.547 | - | - | - | 0.002 | 0.053 | 0.221 | |

| advice_personal | −0.098 | 0.494 | −0.038 | 0.359 | 1 | 0.385 | −0.038 | −0.076 | - | 0.089 | 0.481 | 0.232 | 0.448 | 0.430 | 0.417 | 0.319 |

| 0.369 | - | 0.723 | 0.001 | - | - | 0.729 | 0.486 | 0.996 | 0.412 | - | 0.031 | - | - | - | 0.003 | |

| sympathy | −0.215 | 0.536 | −0.494 | 0.328 | 0.385 | 1 | 0.027 | −0.125 | 0.110 | 0.032 | 0.428 | 0.308 | 0.437 | 0.331 | 0.455 | 0.413 |

| 0.045 | - | 0.000 | 0.002 | - | - | 0.802 | 0.248 | 0.309 | 0.766 | - | 0.004 | - | 0.002 | - | - | |

| hurt | 0.416 | −0.173 | −0.029 | −0.099 | −0.038 | 0.027 | 1 | 0.324 | 0.734 | 0.360 | 0.019 | −0.202 | −0.116 | −0.162 | 0.141 | 0.075 |

| 0.000 | 0.108 | 0.788 | 0.361 | 0.729 | 0.802 | - | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.861 | 0.060 | 0.285 | 0.134 | 0.192 | 0.490 | |

| irony | 0.311 | −0.126 | 0.149 | −0.184 | −0.076 | −0.125 | 0.324 | 1 | 0.353 | 0.243 | −0.112 | −0.324 | −0.034 | −0.099 | −0.020 | −0.098 |

| 0.003 | 0.246 | 0.169 | 0.087 | 0.486 | 0.248 | 0.002 | - | 0.001 | 0.023 | 0.303 | 0.002 | 0.752 | 0.363 | 0.856 | 0.367 | |

| rudeness | 0.419 | −0.106 | 0.008 | −0.069 | 0 | 0.110 | 0.734 | 0.353 | 1 | 0.409 | −0.034 | −0.212 | −0.091 | −0.032 | 0.059 | 0.033 |

| 0.000 | 0.330 | 0.945 | 0.525 | 0.996 | 0.309 | - | 0.001 | - | - | 0.752 | 0.049 | 0.400 | 0.769 | 0.590 | 0.762 | |

| threat | 0.172 | 0.041 | 0.036 | −0.065 | 0.089 | 0.032 | 0.360 | 0.243 | 0.409 | 1 | 0.021 | −0.044 | 0.239 | 0.068 | 0.038 | −0.033 |

| 0.112 | 0.708 | 0.741 | 0.547 | 0.412 | 0.766 | 0.001 | 0.023 | - | - | 0.848 | 0.685 | 0.026 | 0.533 | 0.724 | 0.762 | |

| help_homework | −0.313 | 0.519 | −0.474 | 0.810 | 0.481 | 0.428 | 0.019 | −0.112 | −0.034 | 0.021 | 1 | 0.510 | 0.458 | 0.371 | 0.278 | 0.119 |

| 0.003 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.861 | 0.303 | 0.752 | 0.848 | - | - | - | - | 0.009 | 0.273 | |

| help_homework_others | −0.235 | 0.298 | −0.191 | 0.495 | 0.232 | 0.308 | −0.202 | −0.324 | −0.212 | −0.044 | 0.510 | 1 | 0.236 | 0.198 | 0.266 | 0.194 |

| 0.028 | 0.005 | 0.077 | - | 0.031 | 0.004 | 0.060 | 0.002 | 0.049 | 0.685 | - | - | 0.028 | 0.066 | 0.013 | 0.071 | |

| friendly_to_you | −0.375 | 0.614 | −0.180 | 0.367 | 0.448 | 0.437 | −0.116 | −0.034 | −0.091 | 0.239 | 0.458 | 0.236 | 1 | 0.646 | 0.184 | 0.074 |

| - | - | 0.095 | 0 | - | - | 0.285 | 0.752 | 0.400 | 0.026 | - | 0.028 | - | - | 0.087 | 0.495 | |

| friendly_to_others | −0.246 | 0.639 | −0.173 | 0.326 | 0.430 | 0.331 | −0.162 | −0.099 | −0.032 | 0.068 | 0.371 | 0.198 | 0.646 | 1 | 0.098 | 0.028 |

| 0.022 | 0.000 | 0.108 | 0.002 | - | 0.002 | 0.134 | 0.363 | 0.769 | 0.533 | - | 0.066 | - | - | 0.368 | 0.800 | |

| attractive_to_you | 0.050 | 0.388 | −0.215 | 0.208 | 0.417 | 0.455 | 0.141 | −0.020 | 0.059 | 0.038 | 0.278 | 0.266 | 0.184 | 0.098 | 1 | 0.783 |

| 0.648 | - | 0.046 | 0.053 | - | - | 0.192 | 0.856 | 0.590 | 0.724 | 0.009 | 0.013 | 0.087 | 0.368 | - | - | |

| attractive_to_others | −0.053 | 0.328 | −0.142 | 0.133 | 0.319 | 0.413 | 0.075 | −0.098 | 0.033 | −0.033 | 0.119 | 0.194 | 0.074 | 0.028 | 0.783 | 1 |

| 0.629 | 0.002 | 0.189 | 0.221 | 0.003 | - | 0.490 | 0.367 | 0.762 | 0.762 | 0.273 | 0.071 | 0.495 | 0.800 | - | - | |

| PCA | The Untargeted Powerful | The Targeted Powerful | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Power | Agreement | 0.838 | 0.039 |

| Advice lessons | 0.607 | 0.151 | |

| Sympathy | 0.594 | 0.085 | |

| Advice personal | 0.539 | 0.236 | |

| Social Attraction | Friendly to you | 0.778 | 0.265 |

| Friendly to others | 0.754 | 0.236 | |

| Scientific Attraction | Help homework others | 0.396 | 0.260 |

| Physical Attraction | Attractive to others | 0.296 | −0.834 |

| Attractive to you | 0.348 | −0.785 | |

| Argumentativeness | Disagreement | −0.489 | 0.103 |

| Weakness | −0.317 | 0.099 | |

| Verbal Aggression | Rudeness | −0.282 | 0.346 |

| Threat | −0.112 | 0.335 | |

| Network Variables | Friendship | Attractiveness | Argumentativeness | Verbal Aggressiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondents | 13 | 45 | 42 | 66 |

| Open-ended comments and codes generated | 19 | 45 | 42 | 66 |

| Ranking | Categories | Code Counts | Percent | Theme Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Behaviour and character | 6 | 31% | Traits of personality |

| 2 | Confidentiality | 3 | 16% | Traits of personality |

| 3 | Sense of humor | 3 | 16% | Traits of personality |

| 4 | Fairness | 2 | 10.5% | Traits of personality |

| 5 | Peace and quiet | 2 | 10.5% | Traits of personality |

| 6 | Respectfulness | 2 | 10.5% | Traits of personality |

| 7 | Regular contact | 1 | 5.5% | Traits of friendships |

| Ranking | Categories | Code Counts | Percent | Theme Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Combination of physical appearance, character, personality and behavior | 12 | 30% | Physical and social attractiveness |

| 2 | Attractive physical appearance | 9 | 22.5% | Physical attractiveness |

| 3 | Mutual attractiveness | 8 | 20% | Similarity- attraction principle |

| 4 | Confidentiality | 5 | 12.5% | Power |

| 5 | Smart and helpful | 3 | 7.5% | Scientific attractiveness |

| 6 | Companion | 2 | 5% | Social attractiveness |

| 7 | Similar interests | 1 | 2.5% | Similarity-attraction principle |

| Ranking | Categories | Code Counts | Percent | Theme Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Use of arguments | 17 | 40.5% | Arguing |

| 2 | Persuasion | 9 | 21.5% | Arguing |

| 3 | Support an opinion | 7 | 16% | Arguing |

| 4 | Justification–explanation | 4 | 9.5% | Arguing |

| 5 | Proof | 2 | 5% | Arguing |

| 6 | Public speaking | 2 | 5% | Speaking ability |

| 7 | Excuses | 1 | 2.5% | Other |

| Ranking | Categories | Code Counts | Percent | Theme Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Swearing | 30 | 45% | Verbal aggressiveness |

| 2 | Derogatory comments | 10 | 15% | Verbal aggressiveness |

| 3 | Humiliating others | 7 | 11% | Verbal aggressiveness |

| 4 | Hurting comments | 5 | 8% | Verbal aggressiveness |

| 5 | Pushing–Forcing out | 3 | 4.5% | Physical aggressiveness |

| 6 | Facial aggression | 3 | 4.5% | Non-verbal aggressiveness |

| 7 | Violence | 2 | 3% | Physical aggressiveness |

| 8 | Irony | 2 | 3% | Verbal aggressiveness |

| 9 | Bullying and cyber-bullying | 2 | 3% | Bullying |

| 10 | Threat | 2 | 3% | Verbal aggressiveness |

| Categories | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Behavior and character | Nice behavior; human behavior; nice character; being serious |

| Confidentiality | Keep secrets; trustworthy; gain one’s trust; discretion |

| Sense of humour | Fun to be around; make others laugh |

| Fairness | Just; not exploit others |

| Peace and quiet | Not being nervous; not give on one’s nerves |

| Respectfulness | Respect others’ choices |

| Regular contact | Spend time together |

| Categories | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Combination of physical appearance, character, personality and behaviour | Beauty of body and character; beauty, character, behaviour; mature character, gentle personality, outer beauty; something on someone or their character that attracts; nice appearance, behaviour, respectfulness and being gentle; physical appearance and character |

| Attractive physical appearance | Body that attracts; physical characteristic that attracts; look at someone more often than at others |

| Retrospective attractiveness | When you attract and are attracted; attract and be attracted in a friendly or romantic relationship; be compatible with someone; |

| Confidentiality | Gain confidence by showing love and affection through deeds; |

| Smart and helpful | Smart and helpful; smart, wise, gentle |

| Companion | Others want to approach you and spend time with you |

| Similar interests | The dreams we share |

| Categories | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Use of arguments | The use of arguments during a discussion to show that someone is right; logical and strong arguments |

| Persuasion | Persuade in a nice way and suggest something; use of arguments that make others agree; make others listen to you; persuade others follow; |

| Support an opinion | Support an opinion with arguments; support an opinion and others cannot contradict; support something |

| Justification–explanation | Justify what they say; |

| Proof | Prove that you are right; concrete proof; nice explanation |

| Public speaking | Skillfulness at speaking |

| Excuses | Many excuses |

| Categories | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Swearing | Swearing; swearing and spreading rumors; swear someone that may be better than me; talking dirty; bad phrases |

| Derogatory comments | Make others feel bad about themselves using comments on their appearance or clumsiness |

| Humiliating others | Making someone feel bad about themselves by laughing at them; |

| Hurting comments | Hurting by what they say; words that hurt; phrases that hurt |

| Pushing–Forcing out | Pushing others with no reason; pushing others while swearing; verbal abuse; |

| Facial aggression | Staring at people aggressively |

| Violence | Violence and non-ethical behavior |

| Irony | Ironic comments; |

| Bullying and cyber bullying | Bullying and cyber bullying |

| Threat | Attack by threatening |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Litsa, M.; Bekiari, A. Mixed Methods in Analysis of Aggressiveness and Attractiveness: Understanding PE Class Social Networks with Content Analysis. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12050348

Litsa M, Bekiari A. Mixed Methods in Analysis of Aggressiveness and Attractiveness: Understanding PE Class Social Networks with Content Analysis. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(5):348. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12050348

Chicago/Turabian StyleLitsa, Maria, and Alexandra Bekiari. 2022. "Mixed Methods in Analysis of Aggressiveness and Attractiveness: Understanding PE Class Social Networks with Content Analysis" Education Sciences 12, no. 5: 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12050348

APA StyleLitsa, M., & Bekiari, A. (2022). Mixed Methods in Analysis of Aggressiveness and Attractiveness: Understanding PE Class Social Networks with Content Analysis. Education Sciences, 12(5), 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12050348