A Black Mirror of Bright Ideas: Could Media Educate towards Positive Creativity?

Abstract

:1. Media Content and Creative Self-Beliefs

2. Vicarious Learning through Media

3. A Million Different Ways to Engage: New Media Perspectives for Creativity

4. Reach, Evaluation, and Creative Learning Opportunities

5. Collaboration and Co-Creation: A Creative Selfie

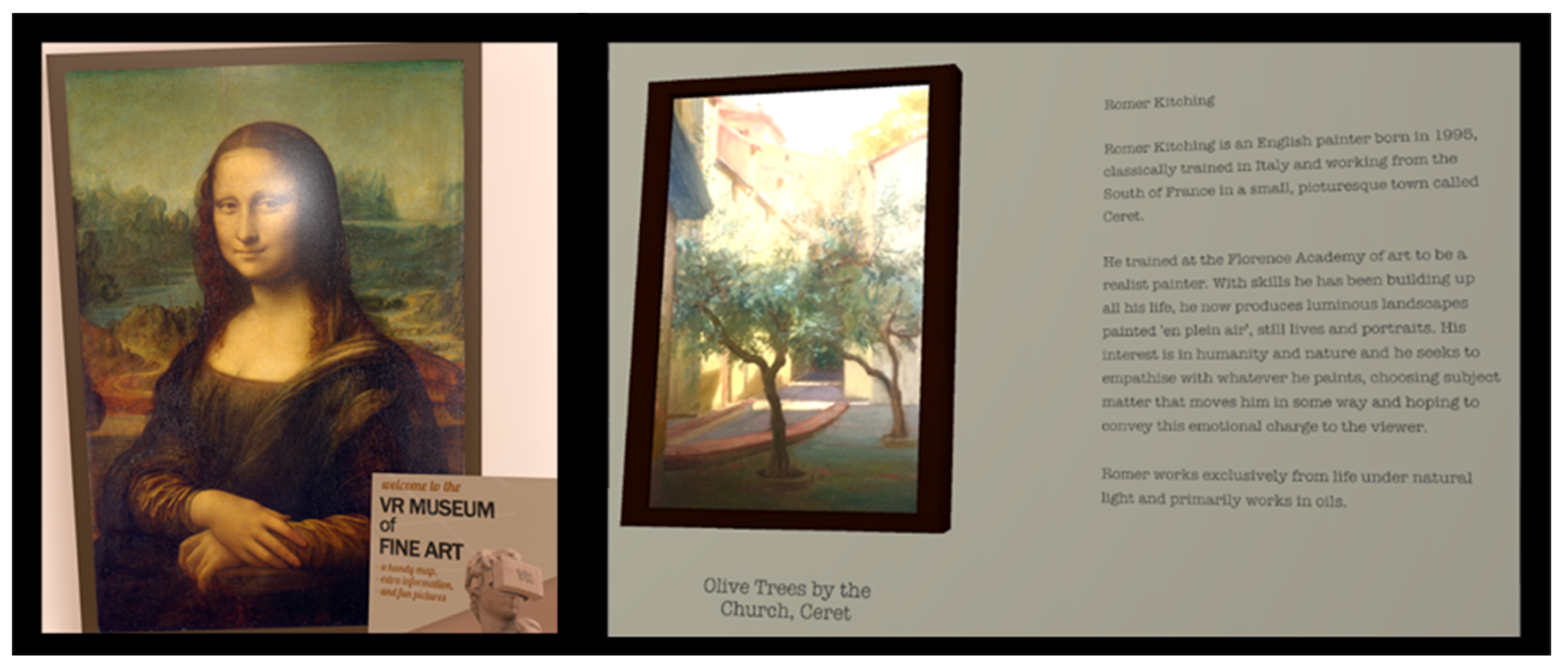

6. Creative Immersion in Games and Virtual Reality

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prescott, J.; Wilson, S.; Becket, G. Facebook use in the learning environment: Do students want this? Learn. Media Technol. 2012, 38, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarella, C.V.; Wagner, T.F.; Kietzmann, J.; McCarthy, I.P. Social media? It’s serious! Understanding the dark side of social media. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, M.A. Creativity and Human Development: The Real Creativity Crisis. 2015. Available online: http://www.creativityjournal.net/index.php/component/k2/item/286-the-real-creativity-crisis (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Cirucci, A.M.; Vacker, B. (Eds.) Black Mirror and Critical Media Theory; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Herrero, D.; Rodríguez-Contreras, L. The risks of new technologies in Black Mirror: A content analysis of the depiction of our current socio-technological reality in a TV series. In ACM International Conference Proceeding Series; ACM International: Florissant, MD, USA, 2019; pp. 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hütter, M.; Sweldens, S. Dissociating Controllable and Uncontrollable Effects of Affective Stimuli on Attitudes and Consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2018, 45, 320–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, N.; Veglis, A.; Gardikiotis, A.; Kotsakis, R.; Kalliris, G. Web Third-person effect in structural aspects of the information on media websites. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 44, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davison, W.P. The Third-Person Effect in Communication. Public Opin. Q. 1983, 47, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, Y.; Pan, Z.; Shen, L. Understanding the Third-Person Perception: Evidence form a Meta-Analysis. J. Commun. 2008, 58, 280–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, E.; Blank, G. The echo chamber is overstated: The moderating effect of political interest and diverse media. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2018, 21, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lachlan, K.A.; Hutter, E.; Gilbert, C. COVID-19 Echo Chambers: Examining the Impact of Conservative and Liberal News Sources on Risk Perception and Response. Health Secur. 2021, 19, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Qian, Y. Echo Chamber Effect in Rumor Rebuttal Discussions about COVID-19 in China: Social Media Content and Network Analysis Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, M.; Karstendiek, M.; Ceh, S.M.; Grabner, R.H.; Krammer, G.; Lebuda, I.; Silvia, P.J.; Cotter, K.N.; Li, Y.; Hu, W.; et al. Creativity myths: Prevalence and correlates of misconceptions on creativity. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 182, 111068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowski, M.; Beghetto, R.A. Creative behavior as agentic action. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2019, 13, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.J. Creativity as a decision. Am. Psychol. 2002, 57, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternberg, R.J. The development of creativity as a decision-making process. In Creativity and Development; Sawyer, R.K., John-Steiner Moran, V.S., Sternberg, R.J., Feldman, D.H., Nakamura, J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 91–138. [Google Scholar]

- Jaussi, K.S.; Randel, A.; Dionne, S.D. I Am, I Think I Can, and I Do: The Role of Personal Identity, Self-Efficacy, and Cross-Application of Experiences in Creativity at Work. Creat. Res. J. 2007, 19, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plucker, J.A.; Makel, M.C. Assessment of creativity. In The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity; Kaufman, J.C., Sternberg, R.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 48–73. [Google Scholar]

- Beghetto, R. Creative Self-Efficacy: Correlates in Middle and Secondary Students. Creat. Res. J. 2006, 18, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M. Creative self-efficacy development and creative performance over time. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M. Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Dewett, T. Exploring the Role of Risk in Employee Creativity. J. Creat. Behav. 2006, 40, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, V.; Hanoch, Y.; Hall, S.D.; Runco, M.; Denham, S.L. The Risky Side of Creativity: Domain Specific Risk Taking in Creative Individuals. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kwaśniewska, J.M.; Lebuda, I. Balancing between the roles and duties—Creativity of mothers. Creat. Theor. –Res. –Appl. 2017, 4, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lebuda, I.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. All You Need Is Love: The Importance of Partner and Family Relations to Highly Creative Individuals’ Well-Being and Success. J. Creat. Behav. 2020, 54, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Condren, M.; Lebuda, I. Deviant heroes and social heroism in everyday life: Activists and artists. In The Handbook of Heroism and Heroic Leadership; Allison, S.T., Goethals, G.R., Kramer, R.M., Eds.; Routledge Press: London, UK, 2016; pp. 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Lebuda, I. Political pathologies and Big-C Creativity—Eminent Polish creators’ experience of restrictions under the communist regime. In The Palgrave Handbook of Creativity and Culture Research; Glăveanu, V.P., Ed.; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 329–354. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory for personal and social change by enabling media. In Entertainment—Education and Social Change: History, Research, and Practice; Singhal, A., Cody, M.J., Rogers, E.M., Sabido, M., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Mass Communication. Media Psychol. 2001, 3, 265–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sestir, M.; Green, M. You are who you watch: Identification and transportation effects on temporary self-concept. Soc. Influ. 2010, 5, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Growing Primacy of Human Agency in Adaptation and Change in the Electronic Era. Eur. Psychol. 2002, 7, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Karwowski, M.; Czerwonka, M.; Lebuda, I.; Jankowska, D.M.; Gajda, A. Does thinking about Einstein make people entity theorists? Examining the malleability of creative mindsets. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2020, 14, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajares, F.; Prestin, A.; Chen, J.A.; Nabi, R.L. Social cognitive theory and mass media effects. In The SAGE Handbook of Media Processes and Effects; Nabi, R.L., Oliver, M.B., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 283–297. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi, R.L.; Krcmar, M. Conceptualizing media enjoyment as attitude: Implications for mass media effects research. Commun. Theory 2004, 14, 288–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.T. DIY videos on YouTube: Identity and possibility in the age of algorithms. First Monday 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, R.L. Cosmetic surgery makeover programs and intentions to undergo cosmetic enhancements: A consideration of three media effects theories. Hum. Commun. Res. 2009, 35, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, R.L.; Clark, S. Exploring the Limits of Social Cognitive Theory: Why Negatively Reinforced Behaviors on TV May Be Modeled Anyway. J. Commun. 2008, 58, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.-C.; Tsai, C.-C. Taiwan college students’ self-efficacy and motivation of learning in online peer assessment environments. Internet High. Educ. 2010, 13, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedding, D.; Niemiec, R.M. Positive Psychology at the Movies: Using Films to Build Virtues and Character Strengths; Hogrefe Publishing: Newburyport, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ceh, S.M.; Benedek, M. Where to Share? A Systematic Investigation of Creative Behavior on Online Platforms. Creat. Theor.–Res.–Appl. 2021, 8, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, S.; Neumayer, M.; Burnett, C. Social Media Use and Creativity: Exploring the Influences on Ideational Behavior and Creative Activity. J. Creat. Behav. 2021, 55, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowski, M.; Brzeski, A. Selfies and the (Creative) Self: A Diary Study. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Upshaw, J.D.; Davis, W.M.; Zabelina, D.L. iCreate: Social media use, divergent thinking, and real-life creative achievement. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2022, 8, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.; Malycha, C.P.; Schafmann, E. The Influence of Intrinsic Motivation and Synergistic Extrinsic Motivators on Creativity and Innovation. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dollinger, S.J.; Burke, P.A.; Gump, N.W. Creativity and values. Creat. Res. J. 2010, 19, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasof, J.; Chen, C.; Himsel, A.; Greenberger, E. Values and Creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2007, 19, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andsager, J.L.; Bemker, V.; Choi, H.L.; Torwel, V. Perceived similarity of exemplar traits and behavior: Effects on message evaluation. Commun. Res. 2006, 33, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Audience identification with media characters. In Psychology of Entertainment; Bryant, J., Vorderer, P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Defining Identification: A Theoretical Look at the Identification of Audiences with Media Characters. Mass Commun. Soc. 2001, 4, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schunk, D.H.; Meece, J.L. Self-efficacy development in adolescence. In Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents; Pajares, F., Urdan, T., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2006; pp. 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Roessler, P. Media Content Diversity: Conceptual Issues and Future Directions for Communication Research. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2007, 31, 464–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Wurff, R. Do audiences receive diverse ideas from news media? Exposure to a variety of news media and personal characteristics as determinants of diversity as received. Eur. J. Commun. 2011, 26, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, F.; Bessi, A.; Del Vicario, M.; Scala, A.; Caldarelli, G.; Shekhtman, L.; Havlin, S.; Quattrociocchi, W. Debunking in a world of tribes. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, P.M. Technology and Informal Education: What Is Taught, What Is Learned. Science 2009, 323, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avcı, Ü.; Ergün, E. Online students’ LMS activities and their effect on engagement, information literacy and academic performance. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2019, 30, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.R.; Chen, T.T. Digital creativity: Research themes and framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 42, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, C. Digital creativity dimension: A new domain for creativity. In Creativity in the Design Process; Springer Series in Design and Innovation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.C.; Glăveanu, V.P. Making the CASE for shadow creativity. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2022, 16, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Literat, I.; Glaveanu, V.P. Distributed creativity on the Internet: A theoretical foundation for online creative participation. Int. J. Commun. 2018, 12, 893–908. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen, D.; Creely, E.; Henderson, M.; Mishra, P. Creativity and technology in teaching and learning: A literature review of the uneasy space of implementation. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2021, 69, 2091–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, C.; Koenitz, H. Bandersnatch, Yea or Nay? Reception and User Experience of an Interactive Digital Narrative Video. In Proceedings of the TVX 2019—2019 ACM International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video, Aveiro, Portugal, 5–7 June 2019; pp. 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, A. Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and Beyond: From Production to Produsage; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ribble, M. Digital Citizenship in the Frame of Global Change. Int. J. Stud. Educ. Sci. 2021, 2, 74–86. Available online: https://ijses.net/index.php/ijses/article/view/30 (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Amabile, T.M. Attributions of Creativity: What Are the Consequences? Creat. Res. J. 1995, 8, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasof, J. Explaining Creativity: The Attributional Perspective. Creat. Res. J. 1995, 8, 311–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Farrell, J.R. More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowski, M.; Jankowska, D.M. Four faces of creativity at school. In Nurturing Creativity in the Classroom; Beghetto, R.A., Kaufman, J.C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 337–354. [Google Scholar]

- Karwowski, M. Creative mindsets: Measurement, correlates, consequences. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2014, 8, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Agrawala, M.; Bernstein, M.S. Mosaic: Designing online creative communities for sharing works-in-progress. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Portland, OR, USA, 25 February–1 March 2017; pp. 246–258. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M. Effects of feedback on individual creativity in social learning: An experimental study. Kybernetes 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter-Palmon, R.; Kramer, W.; Allen, J.A.; Murugavel, V.R.; Leone, S.A. Creativity in Virtual Teams: A Review and Agenda for Future Research. Creat. Theor. –Res. –Appl. 2021, 8, 165–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, D.; Yomogida, I.; Shijun, W.; Okada, T. Exploring the Potential of Art Workshop: An Attempt to Foster People’s Creativity in an Online Environment. Creat. Theor. Res. Appl. 2021, 8, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachher, P.; Levonian, Z.; Cheng, H.F.; Yarosh, S. Understanding community-level conflicts through Reddit r/place. In Conference Companion Publication of the 2020 on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing; Kyushu University Library: Tokyo, Japan, 2020; pp. 401–405. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, F. The VR Museum of Fine Art [Video game]. Sinclair F. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fogden, N. Infinite Art Museum [Video game]. Infinite Art Museum. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Barbot, B.; Kaufman, J.C. What makes immersive virtual reality the ultimate empathy machine? Discerning the underlying mechanisms of change. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 111, 106431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois-Bougrine, S.; Richard, P.; Burkhardt, J.-M.; Frantz, B.; Lubart, T. The Expression of Users’ Creative Potential in Virtual and Real Environments: An Exploratory Study. Creat. Res. J. 2020, 32, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, K.L.; Brooks, P.J.; Aldrich, N.J.; Palladino, M.A.; Alfieri, L. Effects of video-game play on information processing: A meta-analytic investigation. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2013, 20, 1055–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sauce, B.; Liebherr, M.; Judd, N.; Klingberg, T. The impact of digital media on children’s intelligence while controlling for genetic differences in cognition and socioeconomic background. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedek, M.; Jauk, E.; Sommer, M.; Arendasy, M.; Neubauer, A.C. Intelligence, creativity, and cognitive control: The common and differential involvement of executive functions in intelligence and creativity. Intelligence 2014, 46, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guilford, J.P. Creativity: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. J. Creat. Behav. 1967, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A. Creative minecrafters: Cognitive and personality determinants of creativity, novelty, and usefulness in minecraft. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Stickler, U.; Herodotou, C.; Iacovides, I. Expressivity of creativity and creative design considerations in digital games. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 105, 106206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greipl, S.; Moeller, K.; Ninaus, M. Potential and limits of game-based learning. Int. J. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2020, 12, 363–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, P.; Looney, J. Nurturing Creativity in Education. Eur. J. Educ. 2014, 49, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbagh, N.; Kitsantas, A. Personal Learning Environments, social media, and self-regulated learning: A natural formula for connecting formal and informal learning. Internet High. Educ. 2012, 15, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunn, T.; Kennedy, M. Technology Enhanced Learning in higher education; motivations, engagement and academic achievement. Comput. Educ. 2019, 137, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewson, E.R.F. Students’ Emotional Engagement, Motivation and Behaviour over the Life of an Online Course: Reflections on Two Market Research Case Studies. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2018, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muir, T.; Milthorpe, N.; Stone, C.; Dyment, J.; Freeman, E.; Hopwood, B. Chronicling engagement: Students’ experience of online learning over time. Distance Educ. 2019, 40, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhow, C.; Lewin, C. Social media and education: Reconceptualizing the boundaries of formal and informal learning. Learn. Media Technol. 2015, 41, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves-Pereira, M.S. Creativity and Remote Teaching in Pandemic Times: From the Unpredictable to the Possible. Creat. Theor. –Res.–Appl. 2021, 8, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, M.; De Dreu, C.K.W.; Nijstad, B.A. A meta-analysis of 25 years of mood-creativity research: Hedonic tone, activation, or regulatory focus? Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 779–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, M.; Jauk, E.; Kerschenbauer, K.; Anderwald, R.; Grond, L. Creating art: An experience sampling study in the domain of moving image art. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2017, 11, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, T.S.; Silvia, P.J. Creative days: A daily diary study of emotion, personality, and everyday creativity. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2015, 9, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yefet, M.; Glicksohn, J. Examining the Influence of Mood on the Bright Side and the Dark Side of Creativity. J. Creat. Behav. 2020, 55, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A.; Rogers, E.M. A Theoretical Agenda for Entertainment-Education. Commun. Theory 2002, 12, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittman, M. Changing behavior through TV heroes. Monit. Psychol. 2004, 35, 70. [Google Scholar]

- De Saint Laurent, C.; Glaveanu, V.; Chaudet, C. Malevolent Creativity and Social Media: Creating Anti-immigration Communities on Twitter. Creat. Res. J. 2020, 32, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilarinho-Pereira, D.R.; Koehler, A.A.; Fleith, D.D.S. Understanding the Use of Social Media to Foster Student Creativity: A Systematic Literature Review. Creat. Theor. Res. Appl. 2021, 8, 124–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, J.E.; Beentjes, J.W.; Konig, R.P. Mapping Media Literacy Key Concepts and Future Directions. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2008, 32, 313–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ceh, S.M.; Lebuda, I. A Black Mirror of Bright Ideas: Could Media Educate towards Positive Creativity? Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060402

Ceh SM, Lebuda I. A Black Mirror of Bright Ideas: Could Media Educate towards Positive Creativity? Education Sciences. 2022; 12(6):402. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060402

Chicago/Turabian StyleCeh, Simon Majed, and Izabela Lebuda. 2022. "A Black Mirror of Bright Ideas: Could Media Educate towards Positive Creativity?" Education Sciences 12, no. 6: 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060402

APA StyleCeh, S. M., & Lebuda, I. (2022). A Black Mirror of Bright Ideas: Could Media Educate towards Positive Creativity? Education Sciences, 12(6), 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060402