Advancing Engineering Students’ Technical Writing Skills by Implementing Team-Based Learning Instructional Modules in an Existing Laboratory Curriculum

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Design and Implementation of TBL Instructional Modules

3.1. Design of TBL Instructional Modules

- Mini-lecture: A traditional TBL class that requested students to complete the reading assignment prior to the class. However, most students failed to do so and therefore were not able to prepare themselves well. A mini-lecture was delivered by the instructor to cover the technical writing topic in a concise manner, which focused on the conceptual knowledge and common practices relevant to the topic. The mini-lecture typically took 15 min.

- Individual readiness assurance test (iRAT): Five multiple-choice questions were designed in iRAT, which was to evaluate students’ conceptual knowledge of a technical writing topic. Students were asked to complete the iRAT in five minutes, and fill out the answer table by placing points on each equation. An example of iRAT questions is provided in Appendix A, focusing on “Module I: Introduction and Technical Language”. An example of an iRAT answer sheet is provided in Appendix B.

- Team readiness assurance test (tRAT): After iRAT, students in the same team discussed the questions using the immediate feedback assessment technique (IFAT®) in which the correct answers were hidden in the covering for each question. Students were asked to discuss and work together to scratch off the coverings to find the correct answer. The correct answer was denoted as a star under the covering. If a team scratched off covering for one time to expose the correct answer, this team earned 5 points. Otherwise, the more scratching, the fewer points they earned. Most students actively engaged in seeking answers, discussing with teammates, and finalizing their choices. In the end, the instructor collected all teams’ final scores, wrote them on the whiteboard for the class, and announced the winners. All teams were able to see other teams’ scores. This fostered competition among teams, and students enjoyed the competition.

- Appeal: If a team was not satisfied with the earned points, they received a chance to appeal on one question for which they lost the most points. The appeal was held and judged by the instructor like a courtroom, and each team took turns to appeal by stating their reasons. If their appeal failed, they would lose all points of the question they appealed to; if succeeded, they would recover the lost points for that question. The instructor has found that the appeal session greatly inspired students to participate and engage in reasoning and arguing, and teaming up allowed them to work out the problem quickly.

- Application: A small application activity was undertaken after the appeal activity. Each student was asked to practice a 5 min application exercise. Such writing exercises were in versatile forms, such as describing a laboratory experiment procedure, providing an in-text citation and a reference, plotting a chart and inserting it into text with the appropriate title, inserting a table in the text, and describing a sentence with the appropriate embedded equation. The instructor walked around the class and checked students’ writing and provided immediate feedback. Finally, the instructor wrapped up the application exercise and highlighted the critical issues.

- Peer evaluation: Peer evaluation was undertaken to collect each student’s experience in the TBL application and also provided peer pressure on the team. Each student evaluated other teammates’ performance and contributions. An example of a peer evaluation sheet is exhibited in Appendix C. In addition, two questions were included: “What is the single most valuable contribution this person makes to your team?” and “What is the single most important way this person could alter their behavior to more effectively help your team?”

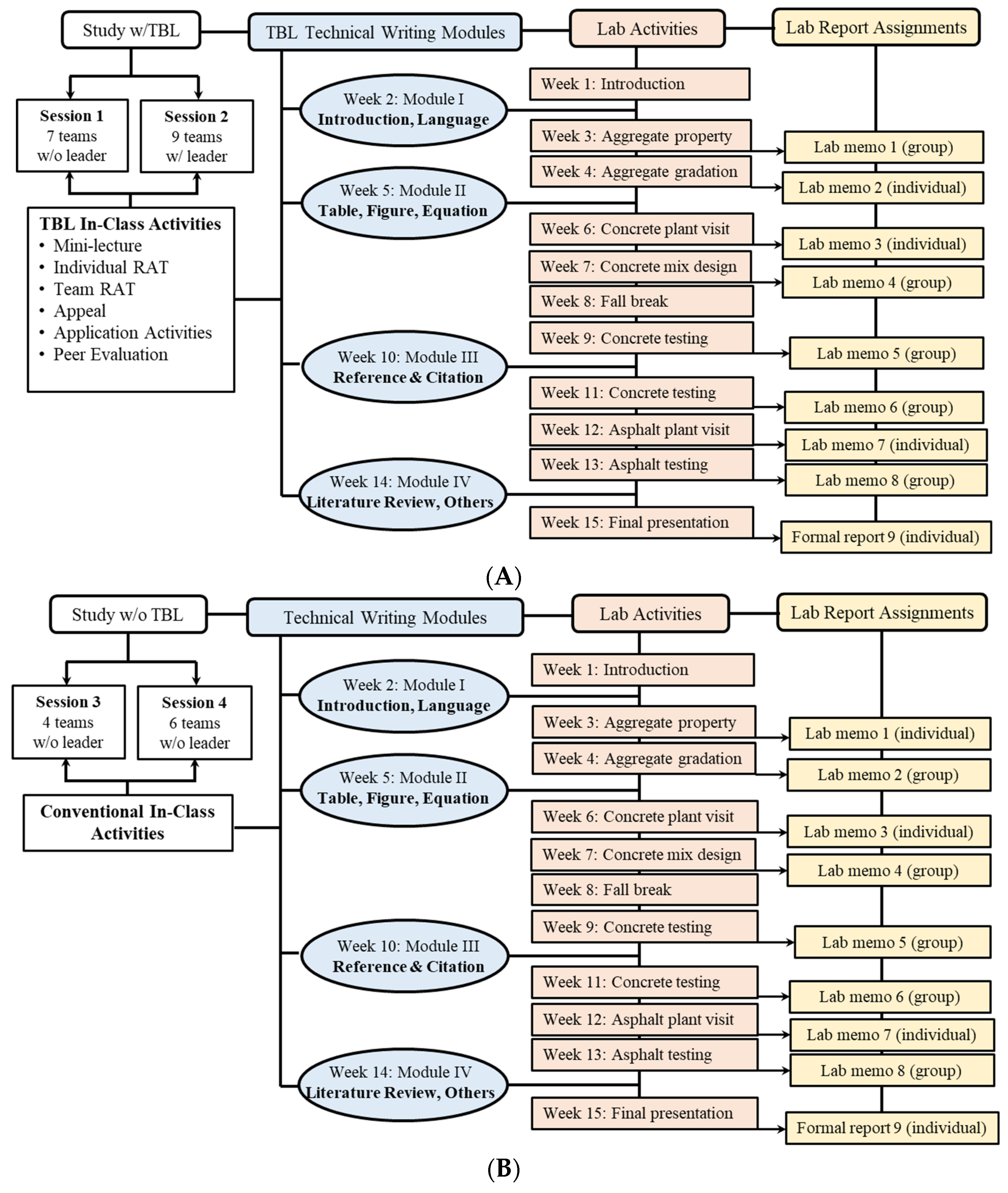

3.2. Design and Implementation of Study

4. Methods

4.1. Student Participants

4.2. Data Collection Procedures

4.2.1. Perception Survey

4.2.2. Technical Writing Evaluation by Instructor

4.3. Data Analysis Procedures

5. Results

5.1. Comparison between Non-TBL and TBL

5.1.1. Students’ Perception of Technical Writing Skills

5.1.2. Instructors’ Perception of Students’ Technical Writing Skills

5.1.3. Correlation between Instructors’ Evaluation and Students’ Perception

5.2. Effect of Team Leader in TBL

5.2.1. Students’ Perception of Technical Writing Skills

5.2.2. Instructors’ Evaluation of Reports: TBL with Team Leader vs. TBL without Team Leader

5.3. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Example of iRAT Module I: Introduction and Technical Language

- Which of the following is inappropriate statement about technical writing?

- Technical writing should be neutral and unbiased.

- Technical writing is to educate students.

- Technical writing should be Fact-based and fact-driven.

- Technical writing can express authors′ opinion from technical point of view.

- Using third-person and passive tense makes technical writing objective.

- ____ introduces a formal list, long quotation, equation, or definition.

- Comma (,)

- Dash (-)

- Semi-Colon (;)

- Colon (:)

- Period (.)

- Run-on is _____.

- two or more independent clauses that are joined properly

- two or more independent clauses that are not joined properly

- group of words that either is missing a subject or a verb or does not express a complete thought

- group of words with a subject and a verb that expresses a complete thought

- group of words that neither is missing a subject nor a verb but express a complete thought

- Read the sentences below:“To conclude this report, I think we had different numbers in each. We have learned the aggregate testing, the specific gravity, and absorption. We used the equations that we took in lecture.”Which is major issue for the above sentences?

- Faulty parallelism

- Unclear pronoun reference

- Vague definition

- Tense inconsistency

- Inappropriate use of number and unit

- For the sentence below, which one is grammar error free?

- Table 1 shows the data of compressive strength and modulus for concrete.

- Smith (2019) shows that lower water-cement ratio result in higher compressive strength.

- Once the drying was completed, we weigh the sample and recorded the amount.

- Future work is needed to work on the correlation between strength and modulus.

- Three different types of recycled materials are studied in this project, recycled glass, recycled steel, and recycled woods.

Appendix B. iRAT Answer Sheet

- Washington, D.C.

- Washington state

- New York

- New York State

- Columbia

| Q # | A | B | C | D | E | Individual Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | ||||||

| 3 | ||||||

| 4 | ||||||

| 5 | ||||||

| Total | ||||||

Appendix C. Peer Evaluation during TBL Application in Class

| Scale | Never | Sometimes | Often | Always |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrives on time and remains with team during activities | ||||

| Demonstrates a good balance of active listening & participation | ||||

| Asks useful or probing questions | ||||

| Shares information and personal understanding | ||||

| Is well prepared for team activities | ||||

| Shows appropriate depth of knowledge | ||||

| Identifies limits of personal knowledge | ||||

| Is clear when explaining things to others | ||||

| Gives useful feedback to others | ||||

| Accepts useful feedback from others | ||||

| Is able to listen and understand what others are saying | ||||

| Shows respect for the opinions and feelings of others |

Appendix D. Survey Questions on Students’ Perception of Their Technical Writing Skills

| No. | Proficiency Statement |

|---|---|

| 1 | I am able to write a project report using the correct format. |

| 2 | I am able to write technical documents with correct grammar. |

| 3 | I am able to write technical documents with correct spelling. |

| 4 | I am able to write technical documents with correct capitalization (capital and small letters). |

| 5 | I am able to write technical documents with correct punctuation. |

| 6 | I am able to construct concise objectives for a project. |

| 7 | I am able to conceptualize a problem |

| 8 | I am able to compose an abstract in a report. |

| 9 | I am able to illustrate a process |

| 10 | I am able to construct figures that present data clearly and precisely. |

| 11 | I am able to construct tables that present data clearly and precisely. |

| 12 | I am able to interpret graphic presentations such as figures and tables. |

| 13 | I am able to analyze data of a research project accurately. |

| 14 | I am able to collate research data |

| 15 | I am able to qualify claims based on gathered data |

| 16 | I am able to transpose verbal data to non-verbal materials and vice versa. |

| 17 | I am able to define technical terms in my own words. |

| 18 | I am able to construct conclusion from research findings in a project report. |

| 19 | I am able to propose recommendations from research findings |

| 20 | I am able to write references for a project report using a correct way. |

| 21 | I am able to differentiate the features of technical reports |

| 22 | I am able to distinguish an opinion from a fact |

| 23 | I am able to spot errors in a technical report |

| 24 | I am able to analyze content of technical reports |

| 25 | I am able to recognize classification of terms according to methods and functions |

| 26 | I am able to distinguish the differences between technical writing and other forms of writing. |

| 27 | I am able to write using various technical writing styles. |

| 28 | I am able to distinguish between formal and informal English in technical writing. |

| 29 | I am able to show that proper ethics are followed in my report. |

Appendix E. Evaluation Rubrics on the Technical Writing Reports

| Criteria | Poor 3 pts | Fair 6 pts | Good 8 pts | Excellent 10 pts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content & Development (20%) | Content is incomplete. Major points are not clear, not persuasive. Equation, figure and table are inappropriate. | Content is not comprehensive or not persuasive. Major points are addressed, but not well supported. Most points required by the assignment are covered. Content is inconsistent with regard to purpose and clarity of thought. Equation, figure and table are appropriate. | Content is somewhat comprehensive, accurate, and persuasive. Major points are mostly clear and supported. Most of the points required by the assignment are covered. Content and purpose of the writing are mostly clear. Equation, figure and table are almost correct. | Content is somewhat comprehensive, accurate, and persuasive. Major points are mostly clear and supported. Most of the points required by the assignment are covered. Content and purpose of the writing are mostly clear. Equation, figure and table are correct and appropriate. |

| Organization & Structure (20%) | Organization and structure detract from the message of the writer. Paragraph is disjointed and lack transition of thoughts. | Structure of the paragraph is not easy to follow. Paragraph transitions need improvement. | Structure of the paragraph is mostly clear and easy to follow. | Structure of the paragraph clear and easy to follow. |

| Format (20%) | Paper lacks many elements of correct formatting. Paragraph is inadequate in length. No citation. | Paper follows some of guidelines. Paper is under word length. Citation is inappropriate. | Paper follows most of designated guidelines. Paper is the appropriate length as described for the assignment. Citation is correct. | Paper follows all the designated guidelines. Paper is the appropriate length as described for the assignment. Correction is correct and include all components. |

| Grammar, Punctuation & Spelling (20%) | Paper contains numerous grammatical, punctuations, and spelling errors. Language uses jargon or conversational tone. | Paper contains few grammatical, punctuations, and spelling errors. Language lacks clarity or includes the use of some jargon or conversational tone. | Rules of grammar, usages, and punctuations are mostly followed; spelling is mostly correct. Language is mostly clear and precise; sentences display good structure. | Rules of grammar, usages, and punctuations are followed; spelling is correct. Language is clear and precise; sentences display consistently strong, varied structure. |

| Conclusion (20%) | There is a 1-2 sentence that does not include all the necessary elements of a closing paragraph. | The conclusion is recognizable, but does not tie up several loose ends. Does not include all the necessary elements of a closing paragraph. | The conclusion is recognizable and ties up almost all the loose ends including restating the thesis. Include all the necessary elements of a paragraph. | The conclusion is strong and leaves the reader satisfied. The thesis statement is restated. Sums up the main topic successfully and leaves a potent final statement. |

References

- Wheeler, E.; McDonald, R.L. Writing in Engineering Courses. J. Eng. Educ. 2013, 89, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET). Accreditation Policy and Procedure Manual Effective for Reviews during the 2022–2023 Accreditation Cycle; ABET Inc.: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.abet.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Ramamuruthy, V.; DeWitt, D.; Alias, N. The Need for Technical Communication Pedagogical Module for 21st Century Learning in TVET Institutions: Lecturers’ Typical Instructional Strategies. Malays. Online J. Educ. Sci. 2021, 9, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Schwebel, D.C. The Challenge of Advanced Scientific Writing: Mistakes and Solutions. Teach. Learn. J. 2021, 14, 22–25. Available online: https://journals.kpu.ca/index.php/td/index (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Cantera, M.A.; Arevalo, M.-J.; García-Marina, V.; Alves-Castro, M. A Rubric to Assess and Improve Technical Writing in Undergraduate Engineering Courses. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyser, G.F.; De Loatch, E.M. Learning Through Writing in an Engineering Course. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 1984, 27, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissbach, R.S.; Pflueger, R.C. Collaborating with Writing Centers on Interdisciplinary Peer Tutor Training to Improve Writing Support for Engineering Students. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2018, 61, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.; Olson, W.M. Using a Transfer-Focused Writing Pedagogy to Improve Undergraduates’ Lab Report Writing in Gateway Engineering Laboratory Courses. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2020, 63, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejene, W. The Practice of Modularized Curriculum in Higher Education Institution: Active Learning and Continuous Assessment in Focus. Cogent Educ. 2019, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, S. A Comparison of Practitioner and Student Writing in Civil Engineering. J. Eng. Educ. 2017, 106, 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumb, C.; Scott, C. Outcomes Assessment of Engineering Writing at the University of Washington. J. Eng. Educ. 2002, 91, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K. Integrating Writing Instruction into Engineering Courses: A Writing Center Model. J. Eng. Educ. 2000, 89, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalvac, B.; Smith, H.D.; Troy, J.B.; Hirsch, P. Promoting Advanced Writing Skills in an Upper-Level Engineering Class. J. Eng. Educ. 2007, 96, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, P.T.; Scarola, L. Using an English Tutor in the Engineering Classroom. J. Eng. Educ. 1998, 87, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, R.A.; Ellis, R.A. Students’ Conceptions of Tutor and Automated Feedback in Professional Writing. J. Eng. Educ. 2010, 99, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitz, I.A.; Barrett, E.C. Integrated Teaching of Experimental and Communication Skills to Undergraduate Aerospace Engineering Students. J. Eng. Educ. 1997, 86, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lerner, N. The Idea of a Writing Laboratory, 9th ed.; Southern Illinois University Press: Carbondale, IL, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-8093-2914-4. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, A.D.; Larios-Sanz, M.; Amin, S.; Rosell, R.C. Using Mini-reports to Teach Scientific Writing to Biology Students. Am. Biol. Teach. 2014, 76, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, R.; Guarienti, K.; Brydon, B.; Robb, J.; Royston, A.; Painter, H.; Sutherland, A.; Passmore, C.; Smith, M.H. Writing Better Lab Reports. Sci. Teach. 2010, 77, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, G.; Hassett, M.F. Developing Critical Writing Skills in Engineering and Technology Students. J. Eng. Educ. 2013, 86, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, S.; Banta, L. Using Log Assignments to Foster Learning: Revisiting Writing Across the Curriculum. J. Eng. Educ. 2000, 89, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, H.H.; Williams, J.M. Using Writing Assignments to Improve Self-Assessment and Communication Skills in an Engineering Statics Course. J. Eng. Educ. 2008, 97, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, A.; Hendrayana, A.; Senjaya, A. Using Project-based Learning in Writing an Educational Article: An Experience Report. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 5, 960–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, Y. Teaching Technical Writing to Engineering Students: Design, Implementation, and Assessment for Project-based Instruction. Interdisciplinary STEM Teaching & Learning Conference. 2019. Available online: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/stem/2019/2019/16 (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Tatzl, D.; Hassler, W.; Messnarz, B.; Flühr, H. The Development of a Project-Based Collaborative Technical Writing Model Founded on Learner Feedback in a Tertiary Aeronautical Engineering Program. J. Tech. Writ. Commun. 2012, 42, 279–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, J.M.; Levis, G.M. A Project-Based Approach to Teaching Research Writing to Nonnative Writers. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2003, 46, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelsen, L.K.; Knight, A.B.; Fink, L.D. Team-Based Learning: A Transformative Use of Small Groups in College Teaching, 1st ed.; Stylus Publishing: Sterling, VA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-1579220860. [Google Scholar]

- Huitt, T.W.; Killin, A.; Brooks, W.S. Team-Based Learning in the Gross Anatomy Laboratory Improves Academic Performance and Students’ Attitudes Toward Teamwork. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2015, 8, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Janke, K.K.; Larson, A.; St. Peter, W. Understanding the Early Effects of Team-Based Learning on Student Accountability and Engagement Using a Three Session TBL Pilot. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2017, 9, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardo, M.T.B.; Hufana, E.R. Development and Evaluation of Modules in Technical Writing. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 2, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isnin, S.F. Exploring the Needs of Technical Writing Competency in English Among Polytechnic Engineering Students. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belser, C.T.; Prescod, D.J.; Daire, A.P.; Cushey, K.F.; Karaki, R.; Yound, C.Y.; Dagley, M.A. The Role of Faculty Guest Speakers and Research Lab Visits in STEM Major Selection: A Qualitative Inquiry. J. Career Tech. Educ. 2018, 33, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hartberg, Y.; Gunersel, A.B.; Simspon, N.; Balester, V. Development of Student Writing in Biochemistry Using Calibrated Peer Review. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 2008, 1, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

| TBL | Lab Session | Students Number | Number of Teams | Non-Native Speaker (%) vs. Native Speaker (%) | Female (%) vs. Male (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without TBL | 3 (without team leader) | 14 | 4 | 0 (0%): 14 (100%) | 4 (29%): 10 (71%) |

| 4 (without team leader) | 22 | 6 | 1 (5%): 21 (95%) | 5 (23%): 17 (77%) | |

| Total | 36 | 10 | 1 (3%): 35 (97%) | 9 (25%): 27 (75%) | |

| With TBL | 1 (without team leader) | 21 | 7 | 1 (5%): 20 (95%) | 6 (29%):15 (71%) |

| 2 (with team leader) | 27 | 9 | 6 (22%): 21 (78%) | 4 (15%): 23 (85%) | |

| Total | 48 | 16 | 7 (15%): 41 (85%) | 10 (21%): 38 (79%) | |

| Overall | 84 | 26 | 8 (10%): 76 (90%) | 19 (23%): 65 (77%) | |

| No. | Technical Writing Skill Dimension | Non-TBL | TBL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Survey | Post-Survey | Ratio | Pre-Survey | Post-Survey | Ratio | ||

| 1 | I am able to write a project report using the correct format. | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 8% | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 17% |

| 2 | I am able to write technical documents with correct grammar. | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 3% | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 10% |

| 3 | I am able to write technical documents with correct spelling. | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 2% | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 9% |

| 4 | I am able to write technical documents with correct capitalization (capital and small letters). | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 3% | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 4% |

| 5 | I am able to write technical documents with correct punctuation. | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 6% | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 13% |

| 6 | I am able to construct concise objectives for a project. | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 11% | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 12% |

| 7 | I am able to conceptualize a problem. | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 7% | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 11% |

| 8 | I am able to compose an abstract in a report. | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 13% | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 27% |

| 9 | I am able to illustrate a process. | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 5% | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 16% |

| 10 | I am able to construct figures that present data clearly and precisely. | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 7% | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 14% |

| 11 | I am able to construct tables that present data clearly and precisely. | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 8% | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 13% |

| 12 | I am able to interpret graphic presentations such as figures and tables. | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 6% | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 9% |

| 13 | I am able to analyze data of a research project accurately. | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 6% | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 18% |

| 14 | I am able to collate research data. | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 11% | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 17% |

| 15 | I am able to qualify claims based on gathered data. | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 8% | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 17% |

| 16 | I am able to transpose verbal data to non-verbal materials and vice versa. | 3.7 ± 0.8 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 14% | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 18% |

| 17 | I am able to define technical terms in my own words. | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 12% | 3.8 ± 1.0 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 17% |

| 18 | I am able to construct conclusion from research findings in a project report. | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 5% | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 13% |

| 19 | I am able to propose recommendations from research findings. | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 4% | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 18% |

| 20 | I am able to write references for a project report using a correct way. | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 11% | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 21% |

| 21 | I am able to differentiate the features of technical reports. | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 16% | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 37% |

| 22 | I am able to distinguish an opinion from a fact. | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 8% | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 3% |

| 23 | I am able to spot errors in a technical report. | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 15% | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 29% |

| 24 | I am able to analyze content of technical reports. | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 14% | 3.7 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 22% |

| 25 | I am able to recognize classification of terms according to methods and functions. | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 12% | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 27% |

| 26 | I am able to distinguish the differences between technical writing and other forms of writing. | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 15% | 3.6 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 23% |

| 27 | I am able to write using various technical writing styles. | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 19% | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 42% |

| 28 | I am able to distinguish between formal and informal English in technical writing. | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 9% | 4.0 ± 0.9 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 15% |

| 29 | I am able to show that proper ethics are followed in my report. | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 4% | 4.0 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 13% |

| Average | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 9% | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 17% | |

| Report No. | Lab Report Content | Non-TBL | TBL | Mann–Whitney p-Value | Significant Difference? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aggregate property | 86 ± 6 | 83 ± 9 | 1.99 | YES |

| 2 | Aggregate gradation | 90 ± 3 | 84 ± 11 | 4.69 | YES |

| 3 | Concrete plant | 97 ± 3 | 95 ± 4 | 1.94 | NO |

| 4 | Concrete mix design and batch | 95 ± 3 | 88 ± 7 | 5.10 | YES |

| 5 | Concrete 7-day test | 87 ± 11 | 86 ± 7 | 1.19 | NO |

| 6 | Concrete 28-day test | 93 ± 5 | 91 ± 6 | 1.00 | NO |

| 7 | Asphalt plant visit | 96 ± 3 | 97 ± 4 | 0.52 | NO |

| 8 | Asphalt test | 88 ± 4 | 93 ± 6 | 5.26 | YES |

| 9 | Final formal report | 88 ± 4 | 93 ± 4 | 4.52 | YES |

| No. | Technical Writing Skill Dimension | No Assigned Team Leader | Assigned Team Leader | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Survey | Post-Survey | Ratio | Pre-Survey | Post-Survey | Ratio | ||

| 1 | I am able to write a project report using the correct format. | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 11% | 3.7 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 22% |

| 2 | I am able to write technical documents with correct grammar. | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 3% | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 16% |

| 3 | I am able to write technical documents with correct spelling. | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 7% | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 10% |

| 4 | I am able to write technical documents with correct capitalization (capital and small letters). | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 0% | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 7% |

| 5 | I am able to write technical documents with correct punctuation. | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 8% | 4.0 ± 0.9 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 17% |

| 6 | I am able to construct concise objectives for a project. | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 3% | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 20% |

| 7 | I am able to conceptualize a problem. | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 6% | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 16% |

| 8 | I am able to compose an abstract in a report. | 3.7 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 23% | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 30% |

| 9 | I am able to illustrate a process. | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 10% | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 22% |

| 10 | I am able to construct figures that present data clearly and precisely. | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 8% | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 20% |

| 11 | I am able to construct tables that present data clearly and precisely. | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 10% | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 16% |

| 12 | I am able to interpret graphic presentations such as figures and tables. | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 4% | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 14% |

| 13 | I am able to analyze data of a research project accurately. | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 8% | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 28% |

| 14 | I am able to collate research data. | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 11% | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 24% |

| 15 | I am able to qualify claims based on gathered data. | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 13% | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 21% |

| 16 | I am able to transpose verbal data to non-verbal materials and vice versa. | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 10% | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 25% |

| 17 | I am able to define technical terms in my own words. | 4.0 ± 0.9 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 10% | 3.6 ± 1.0 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 24% |

| 18 | I am able to construct conclusion from research findings in a project report. | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 7% | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 18% |

| 19 | I am able to propose recommendations from research findings. | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 11% | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 26% |

| 20 | I am able to write references for a project report using a correct way. | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 13% | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 28% |

| 21 | I am able to differentiate the features of technical reports. | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 29% | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 44% |

| 22 | I am able to distinguish an opinion from a fact. | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | −1% | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 6% |

| 23 | I am able to spot errors in a technical report. | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 22% | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 36% |

| 24 | I am able to analyze content of technical reports. | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 15% | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 29% |

| 25 | I am able to recognize classification of terms according to methods and functions. | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 24% | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 29% |

| 26 | I am able to distinguish the differences between technical writing and other forms of writing. | 3.8 ± 1.0 | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 17% | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 28% |

| 27 | I am able to write using various technical writing styles. | 3.0 ± 1.1 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 43% | 3.0 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 41% |

| 28 | I am able to distinguish between formal and informal English in technical writing. | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 5% | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 24% |

| 29 | I am able to show that proper ethics are followed in my report. | 4.2 ± 1.0 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 7% | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 18% |

| Average | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 12% | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 23% | |

| Report No. | Lab Report Content | Without Team Leader | With Team Leader | Mann–Whitney p-Value | Significant Difference? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aggregate property | 81 ± 10 | 83 ± 8 | 0.4354 | NO |

| 2 | Aggregate gradation | 89 ± 5 | 84 ± 11 | 0.34722 | NO |

| 3 | Concrete plant | 97 ± 4 | 94 ± 5 | 0.08364 | NO |

| 4 | Concrete mix design and batch | 92 ± 5 | 87 ± 7 | 0.05486 | NO |

| 5 | Concrete 7-day test | 85 ± 7 | 87 ± 7 | 0.38978 | NO |

| 6 | Concrete 28-day test | 91 ± 7 | 90 ± 6 | 0.61006 | NO |

| 7 | Asphalt plant visit | 96 ± 4 | 97 ± 4 | 0.1096 | NO |

| 8 | Asphalt test | 98 ± 2 | 91 ± 5 | <0.00001 | YES |

| 9 | Final formal report | 93 ± 5 | 95 ± 4 | 0.42952 | NO |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, S.; Zha, S.; Estis, J.; Li, X. Advancing Engineering Students’ Technical Writing Skills by Implementing Team-Based Learning Instructional Modules in an Existing Laboratory Curriculum. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080520

Wu S, Zha S, Estis J, Li X. Advancing Engineering Students’ Technical Writing Skills by Implementing Team-Based Learning Instructional Modules in an Existing Laboratory Curriculum. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(8):520. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080520

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Shenghua, Shenghua Zha, Julie Estis, and Xiaojun Li. 2022. "Advancing Engineering Students’ Technical Writing Skills by Implementing Team-Based Learning Instructional Modules in an Existing Laboratory Curriculum" Education Sciences 12, no. 8: 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080520