Enhancing Learning in Tourism Education by Combining Learning by Doing and Team Coaching

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Combined Use of LBD and Team Coaching

1.1.1. Learning by Doing

- Motivation and emotional involvement. Some students show over-motivation. In many cases, some students will use their better preparation, superior communication and persuasion skills, extroverted personality, reputation, or seniority to dominate others and impose their preferred solutions.

- Uncertainty. Instructors structure and frame the problem. However, the student is an active part of the process and responsible for the content and learning dynamics. Sometimes the problem is not clearly defined, therefore leading to confusion and even disorientation.

- Alienation. This stems from a lack of interest, communication problems, not knowing how to work in a team, or the personal characteristics of the students (shyness, apathy, etc.).

- Hostility. Although in general, most students prefer LBD, some students are not comfortable with experiential learning and prefer traditional methods.

1.1.2. Facilitating LBD through Team Coaching

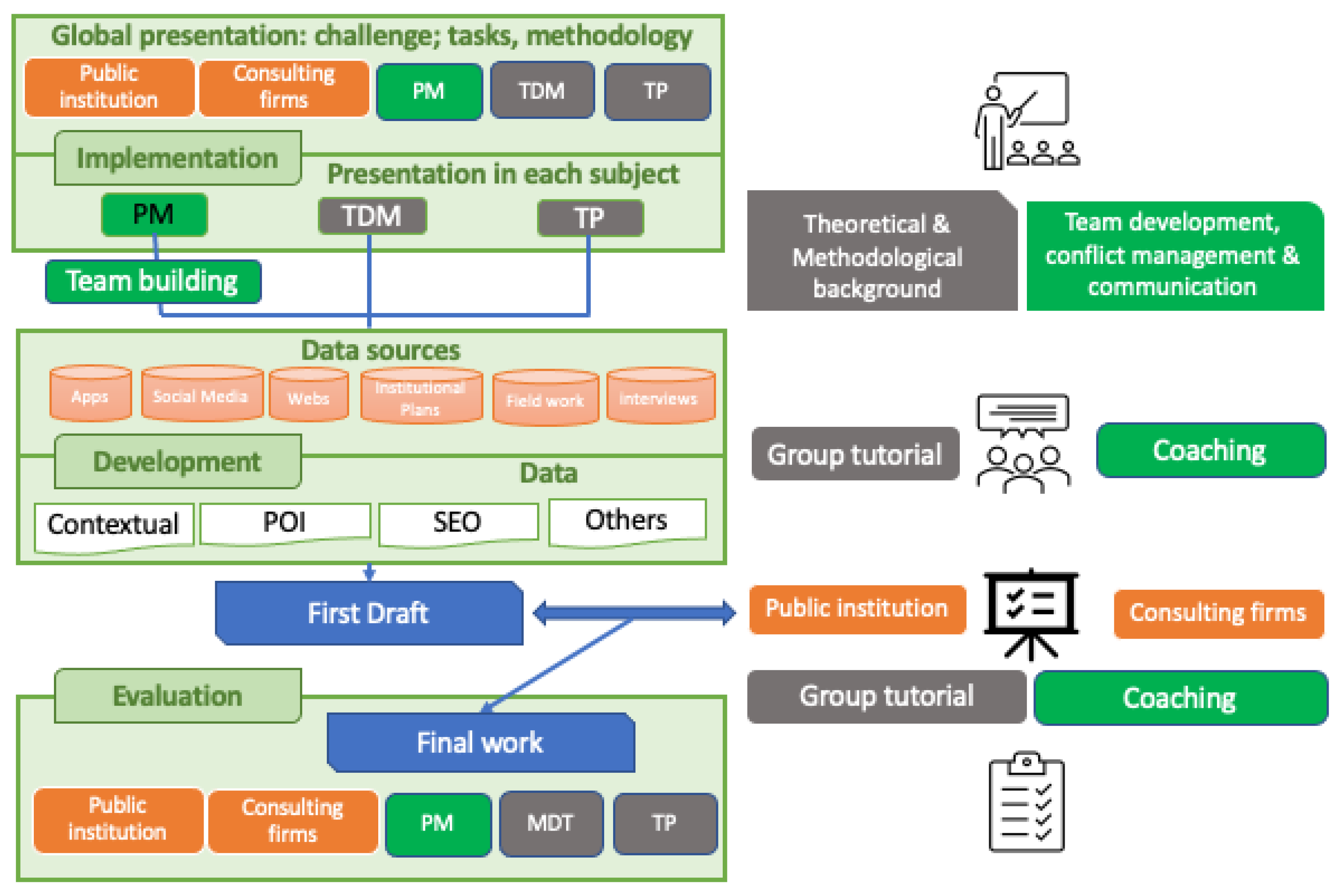

2. Project Design

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

3.2. Project Evaluation

4. Results

4.1. Positive Aspects of Team Coaching and LBD

4.1.1. Team Performance and Engagement

“I think that we learned to connect and work better”(S4#)

“It has helped define our common goal”(S9#)

“Group coaching encourages open conversations”(S11#)

“We had serious and deep conversations”(S14#)

“We know ourselves and others better”(S21#)

“We know each other better and we understand the positive aspects of each one”(S24#)

“Group coaching enhanced transparency and improved our communication, leading to better outcomes”(S105#)

“Knowing the roles of each member is useful to work in a more efficient way”(S112#)

“We worked better, because even if we had a team crisis, after these sessions and our own meeting we could solve the situation”(S97#)

“I think that it motivated us and made us participate more in the group, and as a consequence, we were more engaged”(S114#)

“Group coaching improved the motivation level of the team, and we were more committed to the assignments”(S115#)

“It was helpful for improving our cohesiveness”(S118#)

“The sessions made the group stronger, and we felt part of something important”(S120#)

4.1.2. Coach

“It was a nice time to talk about our problems and solve them with external help”(S34#)

“We could talk about and discuss our problems and we had a professional opinion”(S35#)

“Team coaching was helpful in finding solutions to problems”

4.1.3. Skills Development

“It has improved our behavior and individual skills”(S47#)

“It improved our confidence”(S48#)

4.2. Negative Aspects of Team Coaching

“Not everyone participated in the sessions”(S58#)

“Not all the members gave an opinion in each coaching session”(S59#)

“The team coaching process was too short”(S65#)

“There were not enough sessions”(S66#)

“Maybe it was a little time consuming”(S68#)

4.3. Recommendations to Enhance Learning by the Combination of Learning by Doing and Coaching

“Having more sessions would be helpful for team performance and engagement”(S129#)

“I would like to have coaching sessions in all subjects”(S123#)

“The instructor should encourage all the participants to speak in the coaching sessions at least for two minutes or have at least two compulsory minutes each to speak in every session. That would improve our results and motivation”(S137#)

“The instructor should take more control of the members that do not speak in the sessions to make sure that we are all engaged”(S140#)

“Focus the coaching more on the explanation of tasks and activities rather than on team’s internal situation”(S142#)

“Encourage students to be open-minded and resourceful to take advantage of the sessions”(S144#)

“Encourage students to let all emotions out, leave it all inside the sessions and not to take it personally”(S145#)

5. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernández-Villarán, A.; Rodríguez-Zulaica, A.; Ageitos, N.; Lecuona, M.J. El Aprendizaje basado en problemas como metodología docente. In Innovación docente en Educación Superior. Buenas prácticas que nos inspiran; Eizaguirre, A., Bezanilla, M.J., García Olalla, A., Eds.; Pearson: Madrid, Spain, 2008; pp. 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer, M.R.; Otting, H. Student’s Voice in Problem-based learning: Personal experiences, thoughts and feelings. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2011, 23, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Lopa, J.M.; Elsayed, Y.N.M.K.; Wray, M.L. The State of Active Learning in the Hospitality Classroom. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2018, 30, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, L.; Barreira, E.M.; Rial, A. Formación profesional dual: Comparativa entre el sistema alemán y el incipiente modelo español. Rev. Esp. Educ. Comp. 2015, 25, 149–166. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Villarán, A.; Rodríguez, A. El binomio universidad-empresa en el diseño curricular de asignaturas de Grado. In Espacios de aprendizaje en Educación Superior; Eizaguirre, A., Bezanilla, M.J., Arruti y Nerea Sáenz, A., Eds.; Octaedro: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Hains, B.J.; Smith, B. Student-centered course design: Empowering students to become self-directed learners. J. Exp. Educ. 2012, 35, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargallo, B.; Morera, I.; García, E. Metodología innovadora en la universidad: Sus efectos sobre los procesos de aprendizaje de los estudiantes universitarios. An. Psicol. 2015, 31, 901–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, C.V.; Coelho, A. Game-Based Learning, Gamification in Education and Serious Games. Computers 2022, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krath, J.; Schürmann, L.; von Korflesch, H.F.O. Revealing the theoretical basis of gamification: A systematic review and analysis of theory in research on gamification, serious games and game-based learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 125, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Simon, A.; Bech, S.; Bæntsen, K.; Forchhammer, S. Defining immersion: Literature review and implications for research on audiovisual experiences. J. Audio Eng. Soc. 2020, 68, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, D.; Bilgram, V. Gamification: Best practices in research and tourism. In Open Tourism; Egger, R., Gula, I., Walcher, D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 363–370. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Buhalis, D.; Weber, J. Serious games and the gamification of tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.; Buzady, Z.; Ferro, A. Exploring the role of a serious game in developing competencies in higher tourism education. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 29, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortara, M.; Catalano, C.E.; Bellotti, F.; Fiucci, G.; Houry-Panchetti, M.; Petridis, P. Learning cultural heritage by serious games. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A.; Carter, L. Serious games as interpretive tools in complex natural tourist attractions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Gamification for Crowdsourcing Marketing Practices: Applications and Benefits in Tourism. In Advances in Crowdsourcing; Garrigos-Simon, F.J., Gil-Pechuán, I., Estelles-Miguel, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Bot, L.; Gossiaux, P.-B.; Rauch, C.-P.; Tabiou, S. ‘Learning by Doing’: A teaching method for active learning in scientific graduate education. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2005, 30, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, A.W. Teaching in a Digital Age: Guidelines for Designing Teaching and Learning. 2015. Available online: https://opentextbc.ca/teachinginadigitalage/ (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Bradberry, L.; De Maio, J. Learning by Doing: The Long-Term Impact of Experiential Learning Programs on Student Success. J. Political Sci. Educ. Simul. Games 2019, 15, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, J.A. Learning by doing. NACTA J. 2011, 55, 98–99. [Google Scholar]

- Tabak, F.; Lebron, M. Learning by Doing in Leadership Education: Experiencing Followership and Effective Leadership Communication through Role-Play. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2017, 16, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. A comparison of student perceptions of learning in their co-op and internship experiences and the classroom environment: A study of hospitality management students. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mikalayeva, L. Motivation, Ownership, and the Role of the Instructor in Active Learning. Int. Stud. Perspect. 2016, 17, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selingo, J. There is Life after College; William Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöstedt, R. Assessing A Broad Teaching Approach: The Impact of Combining Active Learning Methods on Student Performance In Undergraduate Peace And Conflict Studies. J. Political Sci. Educ. 2015, 11, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, F.; García-Carbonell, A.; Rising, B. Student Perceptions of Collaborative Work in Telematic Simulation. J. Simul. Gaming Learn. Dev. 2011, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, P.M.C.; Hanqin Qiu, Y.K.; Ren, L. Experiential Learning in Hospitality Education through a Service-Learning Project. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2017, 29, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnesota State University. Experiential Education: Internships and Work-Based Learning. A Handbook for Practitioners and Administrators. 2017. Available online: https://www.minnstate.edu/system/asa/workforce/docs/experiential_learningv4.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Hickman, M.; Stokes, P. Beyond learning by doing: An exploration of critical incidents in outdoor leadership education. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2016, 16, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, C.S. Measuring the value of experiential learning. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 1990, 31, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, K. The Role of Experiential Learning in Nurturing Management Competencies in Hospitality and Tourism Management Students: Perceptions from Students, Faculty, and Industry Professionals. Ph.D. Thesis, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Černá, M. Increasing Team Skills of Students of Tourism by Problem-Based Learning. Paidagog. J. Educ. Contexts 2014, 1, 156–167. [Google Scholar]

- Morellato, M. Digital Competence in Tourism Education: Cooperative-experiential Learning. J. Teach. Travel Tour. Tour. Educ. Glob. Citizensh. 2014, 14, 184–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Best, G. Short Study Tours Abroad: Internationalizing Business Curricula. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2014, 14, 240–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Caton, K.; Hill, D. Lessons from the Road: Travel, Lifewide Learning, and Higher Education. J. Teach. Travel Tour. Transform. Learn. Act. Empower. Political Agency Tour. Educ. 2015, 15, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A. Using Scenario-Based Learning to Teach Tourism Management at the Master’s Level. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2015, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitompul, S.; Kustono, D.; Suhartadi, S.; Setyaningsih, R. The Relationship of the Learning of Tourism Marketing, Hard Skills, Soft Skills and Working Quality of the Graduates of Tourism Academy in Medan. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Stud. 2017, 3, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosan, C.; Dawson, M.; Whalen, E.A. Using Active Learning Activities to Increase Student Outcomes in an Information Technology Course. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2017, 29, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, X.; Aubke, F. Experience care: Efficacy of service-learning in fostering perspective transformation in tourism education. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2018, 18, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer-Silveira, J.C. A multimodal approach to business presentations for the tourism industry: Learning communication skills in a master’s programme. Iberica 2019, 37., 39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Machingambi, S. Enhancing the hospitality student learning experience through student engagement: An analysis. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2020, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou, J.F. Coaching para Docentes: El Desarrollo de Habilidades en el Aula; Editorial Club Universitario: San Vicente, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hargrove, R. Masterful Coaching; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore, J. Coaching for Performance, 3rd ed.; Nicholas Brealey Publishing: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, G.; Castagna, C.; Moir, E.; Warren, B. Blended Coaching: Skills and Strategies to Support Principal Development; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tolhurst, J. The Essential Guide to Coaching and Mentoring; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.Y.; Pirola-Merlo, A.; Yang, C.A.; Huang, C. Disseminating the functions of team coaching regarding research and development team effectiveness: Evidence from high-tech industries in Taiwan. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2009, 37, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimbecker, D.R. The Effects of Expert Coaching on Team Productivity at the South Coast Educational Collaborative. Ph.D. Thesis, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Buljac-Samardzic, M. Healthy Teams: Analyzing and Improving Team Performance in Long Term Care. Ph.D. Thesis, Erasmus Universeit, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Garmston, R.; Linder, C.; Whitaker, J. Reflections on cognitive coaching. Educ. Leadersh. 1993, 51, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A.; Garmston, R. Cognitive coaching: A strategy for reflective teaching. In Northeast Georgia RESA. Teacher Support Specialist Instructional Handbook; Northeast Georgia RESA: Winterville, GA, USA, 1992; pp. 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A.L.; Garmston, R.J. Cognitive Coaching: Developing Self-Directed Leaders and Learners; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Skiffington, S.; Zeus, P. The Complete Guide to Coaching at Work; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, K. Personal coaching: A model for effective learning. J. Learn. Des. 2005, 1, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, L.; Kimsey-House, H.; Sandahl, P. Co-Active Coaching; Davies Blade Publishing: Mountain View, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Skiffington, S.; Zeus, P. Behavioral Coaching: How to Build Sustainable Personal and Organizational Strength; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, J.R.; Wageman, R. A theory of team coaching. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rué, J.; Amador, M.; Gené, J.; Rambla, F.X.; Pividori, I.; Torres-Hostench, O.; Bosco, A.; Armengol, J.; Font, A. Evaluar la calidad del aprendizaje en Educación Superior: El modelo ECA08 como base para el análisis de evidencias sobre la calidad de la E-A en Educación Superior. Red U. Rev. Docencia Univ. 2008, 7, 3. Available online: http://www.um.es/ead/Red_U/3/ (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, A.; Poblete, M. Aprendizaje Basado en Competencias, una Propuesta para la Elaboración de las Competencias Genéricas. Vicerrectorado de Innovación y Calidad; ICE Universidad de Deusto: Bilbao, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, M.J.; Feather, N. Some Correlates of Structure and Purpose in the Use of Time. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 55, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, B.K.; Tesser, A. Effects of time-management practices on college grades. J. Educ. Psychol. 1991, 83, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macan, T.H. Time management: Test of a process model. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation | 3.69 | 1.01 |

| Perceived team performance | 3.96 | 0.66 |

| Learning-teaching methodology | 3.80 | 0.92 |

| I understand the evaluation criteria | 4.46 | 0.50 |

| The learning objectives are clear | 4.27 | 0.66 |

| The professors provided accessible tutorial support | 4.19 | 0.80 |

| The project has allowed me to apply what I studied to real situations | 4.15 | 0.73 |

| I have analyzed information and developed conclusions | 4.12 | 0.51 |

| The project has allowed me to work on professional realities | 4.08 | 0.84 |

| The project has allowed me to exchange ideas and learn with my classmates | 4.04 | 0.66 |

| I have been able to design and develop proposals | 4.04 | 0.72 |

| I have had spaces for personal initiative | 4.00 | 0.69 |

| I have been able to develop activities with my own criteria | 3.77 | 0.81 |

| The project has allowed me to manage personal relationships in the work carried out | 3.73 | 0.91 |

| The project has allowed me to relate the new information to what I already knew | 3.58 | 0.75 |

| I had sufficient information and documents to carry out the activity | 3.50 | 1.03 |

| The project has allowed me to understand the theoretical background of the subjects | 3.38 | 1.02 |

| The workload was adequate for the objectives | 3.23 | 1.27 |

| The amount of work was adequate | 3.00 | 1.16 |

| Coordination between courses has been adequate | 2.96 | 1.11 |

| Collaboration with public institutions | 3.58 | 1.00 |

| The public institutions provided helpful feedback | 3.69 | 0.67 |

| The experience exchange with the public institutions has been enriching | 3.58 | 1.13 |

| The public institutions have been accessible and supportive | 3.46 | 1.14 |

| Theme | Subtheme | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Team performance | Group dynamics | Students find that group coaching enhances group dynamics |

| Communication | Students find that group coaching fosters communication among team members | |

| Awareness of self and others | Students find that group coaching helps them know and understand themselves and others | |

| Conflict management | Students find that group coaching helps to find solutions to problems | |

| Coach | Support from the coach | Students value the support and guidance of the coach |

| Skill development | Development of individual skills | Students find that group coaching is helpful for developing individual skills |

| Theme | Subtheme | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Team performance | Communication | Students find that group coaching fosters team performance through the improvement of communication among team members |

| Awareness of self and others | Students find that group coaching supports team performance through a deeper understanding of themselves and others | |

| Conflict management | Students find that group coaching enhances team performance by supporting problem-solving processes | |

| Engagement | Motivation | Students find that group coaching improves students’ engagement by increasing their motivation |

| Group cohesion | Students find that group coaching improves students’ engagement by increasing their group cohesion |

| Theme | Definition |

|---|---|

| Participation | Students find that some students did not participate in the sessions |

| Duration | Students find that the number of sessions was inadequate |

| Skill development | Students find that group coaching is helpful for developing individual skills |

| Theme | Definition |

|---|---|

| Duration | Students find that increasing the duration of group coaching sessions would be helpful |

| Participation | Students find that encouraging participation of team members would be helpful |

| Content | Students indicate that the content of the sessions should focus on task-related issues |

| Training | Students find that providing training to students would be helpful |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Azanza, G.; Fernández-Villarán, A.; Goytia, A. Enhancing Learning in Tourism Education by Combining Learning by Doing and Team Coaching. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 548. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080548

Azanza G, Fernández-Villarán A, Goytia A. Enhancing Learning in Tourism Education by Combining Learning by Doing and Team Coaching. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(8):548. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080548

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzanza, Garazi, Asunción Fernández-Villarán, and Ana Goytia. 2022. "Enhancing Learning in Tourism Education by Combining Learning by Doing and Team Coaching" Education Sciences 12, no. 8: 548. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080548

APA StyleAzanza, G., Fernández-Villarán, A., & Goytia, A. (2022). Enhancing Learning in Tourism Education by Combining Learning by Doing and Team Coaching. Education Sciences, 12(8), 548. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080548