A Non-Randomised Controlled Study of Interventions Embedded in the Curriculum to Improve Student Wellbeing at University

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Objectives

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Setting

2.2. Sample Size

2.3. Interventions

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Factor Analysis to Determine Wellbeing Measures

2.6. Time 2 Survey Measures

2.7. Blinding

2.8. Statistical Methods

3. Results

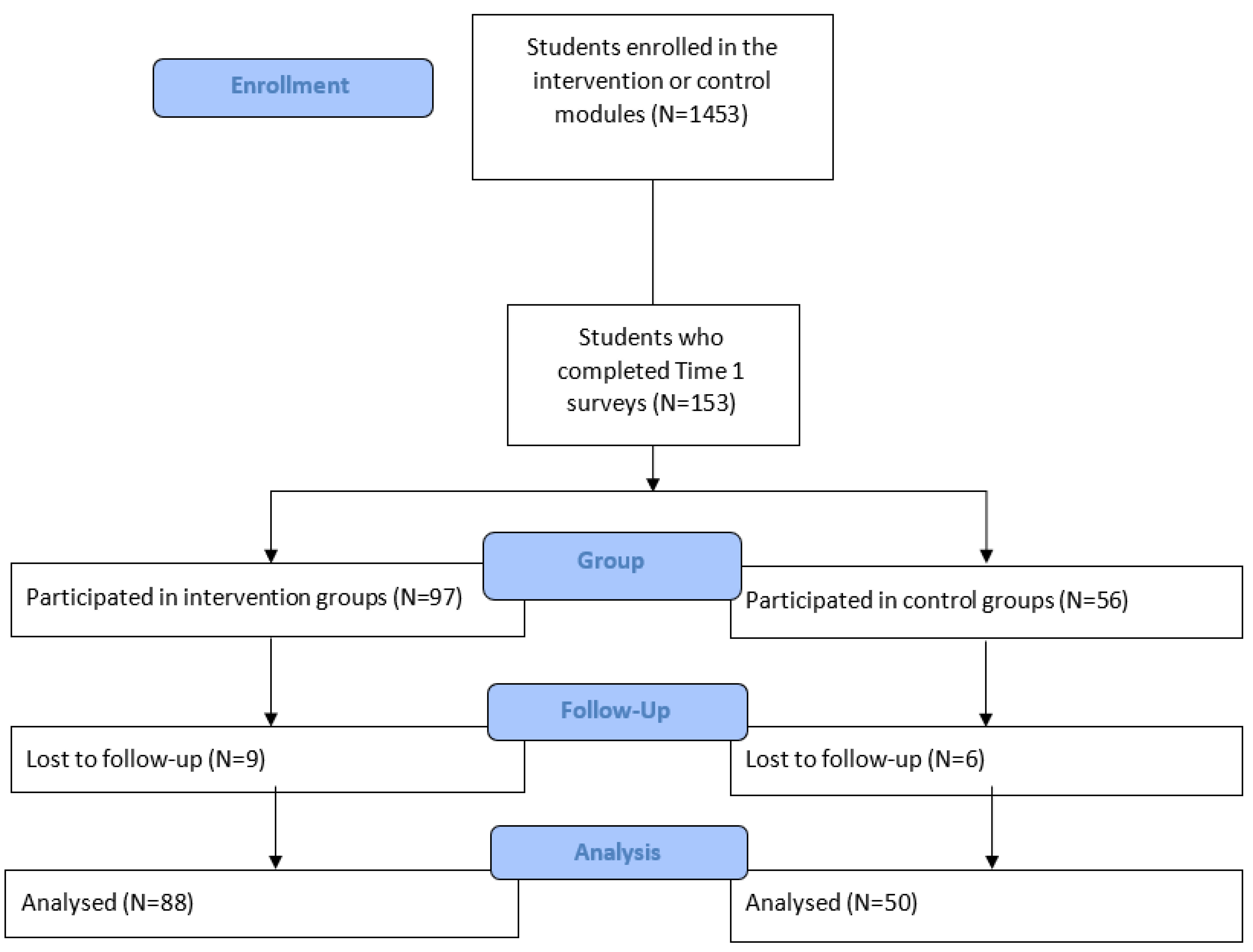

3.1. Participant Flow

3.2. Baseline Data

3.3. Outcomes and Estimation

3.4. Wellbeing Outcomes

3.5. Learning Approach

3.6. Views on Embedding Wellbeing in the Curriculum

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Generalisability

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McManus, S. General Population Surveys: Comparing Student and Non-Student Mental Health. 2019. Available online: https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/general-population-surveys(5f7c10f4-b901-441d-878f-55a9826e725e).html (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Mortier, P.; Auerbach, R.P.; Alonso, J.; Axinn, W.G.; Cuijpers, P.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hwang, I.; Kessler, R.C.; Liu, H.; et al. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among college students and same-aged peers: Results from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabor, E.; Patalay, P.; Bann, D. Mental health in higher education students and non-students: Evidence from a nationally representative panel study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auerbach, R.P.; Alonso, J.; Axinn, W.G.; Cuijpers, P.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hwang, I.; Kessler, R.C.; Liu, H.; Mortier, P.; et al. Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 2955–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auerbach, R.P.; Mortier, P.; Bruffaerts, R.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hasking, P.; et al. WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2018, 127, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubble, S.; Bolton, P. Support for Students with Mental Health Issues in Higher Education in England. 2020. Available online: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8593/CBP-8593.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Thorley, C. Not by Degrees: Improving Student Mental Health in the UK’s Universities; IPPR: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lipson, S.K.; Lattie, E.G.; Eisenberg, D. Increased rates of mental health service utilization by US college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orygen. Under the Radar: The Mental Health of Australian University Students; Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health: Parkville, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barkham, M.; Broglia, E.; Dufour, G.; Fudge, M.; Knowles, L.; Percy, A.; Turner, A.; Williams, C.; SCORE Consortium. Towards an evidence-base for student wellbeing and mental health: Definitions, developmental transitions and data sets. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2019, 19, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broglia, E.; Millings, A.; Barkham, M. Challenges to addressing student mental health in embedded counselling services: A survey of UK higher and further education institutions. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2018, 46, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G.J.; Spanner, L.; The University Mental Health Charter. Student Minds. 2019. Available online: https://www.studentminds.org.uk/charter.html (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- WHO. Health Promotion: Ottawa Charter. 1995. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/59557/Ottawa_Charter_G.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Ashton, J. The historical shift in public health. In Health Promoting Universities: Concept, Experience and Framework for Action; Tsouros, A.D., Dowding, G., Thompson, J., Dooris, M., Eds.; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/108095/9789289012850-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Taylor, P.; Saheb, R.; Howse, E. Creating healthier graduates, campuses and communities: Why Australia needs to invest in health promoting universities. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2019, 30, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, A.M.; Anderson, J. Embedding Mental Wellbeing in the Curriculum: Maximising Success in Higher Education. Higher Education Academy, 2017. Available online: https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets.creode.advancehe-document-manager/documents/hea/private/hub/download/embedding_wellbeing_in_he_1568037359.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Burgess, S.; Greaves, E. Test Scores, Subjective Assessment, and Stereotyping of Ethnic Minorities. J. Labor Econ. 2013, 31, 535–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putwain, D.; Sander, P.; Larkin, D. Academic self-efficacy in study-related skills and behaviours: Relations with learning-related emotions and academic success. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 83, 633–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G.; Upsher, R.; Nobili, A.; Kirkman, A.; Wilson, C.; Bowers-Brown, T.; Foster, J.; Bradley, S.; Byrom, N.; Education for Mental Health. Advance HE. 2022. Available online: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/teaching-and-learning/curricula-development/education-mental-health-toolkit (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Worsley, J.; Pennington, A.; Corcoran, R. What Interventions Improve College and University Students’ Mental Health and Wellbeing? A Review of Review-Level Evidence. 2020. Available online: https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3089948/1/Student-mental-health-full-review%202020.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Fernandez, A.; Howse, E.; Rubio-Valera, M.; Thorncraft, K.; Noone, J.; Luu, X.; Veness, B.; Leech, M.; Llewellyn, G.; Salvador-Carulla, L. Setting-based interventions to promote mental health at the university: A systematic review. Int. J. Public Health 2016, 61, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upsher, R.; Nobili, A.; Hughes, G.; Byrom, N. A systematic review of interventions embedded in curriculum to improve university student wellbeing. Educ. Res. Rev. 2022, 37, 100464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.M.; Keough, K.A.; Sexton, J.D. Social connectedness, social appraisal, and perceived stress in college women and men. J. Couns. Dev. 2002, 80, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, F. Psychometric analysis of the short-form UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-6) in older adults. Eur. J. Ageing 2014, 11, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart-Brown, S.; Tennant, A.; Tennant, R.; Platt, S.; Parkinson, J.; Weich, S. Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): A Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish health education population survey. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2009, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.-W.; Oishi, S.; Biswas-Diener, R. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F.; Pommier, E.; Neff, K.D.; Van Gucht, D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2011, 18, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, R.W.; Hendin, H.M.; Trzesniewski, K.H. Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, B.; Gaus, W. Guidelines for reporting non-randomised studies. Complement. Med. Res. 2004, 11 (Suppl. S1), 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, R.; Bachteler, T.; Reiher, J. Improving the use of self-generated identification codes. Eval. Rev. 2010, 34, 391–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penberthy, J.K.; Williams, S.; Hook, J.N.; Le, N.; Bloch, J.; Forsyth, J.; Schorling, J. Impact of a Tibetan Buddhist Meditation Course and Application of Related Modern Contemplative Practices on College Students’ Psychological Well-Being: A Pilot Study. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.; Glasziou, P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Gesundheitswesen 2016, 78, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kift, S. The next, great first year challenge: Sustaining, coordinating and embedding coherent institution-wide approaches to enact the FYE as everybody’s business. In Proceedings of the 11th Pacific Rim First Year in Higher Education Conference 2008, Hobart, TAS, Australia, 30 June–2 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, J.; Kember, D.; Leung, D.Y. The revised two-factor study process questionnaire: R-SPQ-2F. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 71, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelamour, B.; George Mwangi, C.; Ezeofor, I. “We need to stick together for survival”: Black college students’ racial identity, same-ethnic friendships, and campus connectedness. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2019, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fat, L.N.; Scholes, S.; Boniface, S.; Mindell, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): Findings from the Health Survey for England. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 1129–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.J.; Buro, K. Measuring and predicting student well-being: Further evidence in support of the flourishing scale and the scale of positive and negative experiences. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 121, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, R.B. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1966, 1, 245–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurstone, L.L. Multiple-Factor Analysis; a Development and Expansion of The Vectors of Mind; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Stata, A. Stata Base Reference Manual Release 14; Press Publications: College Station, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Baik, C.; Larcombe, W.; Brooker, A. How universities can enhance student mental wellbeing: The student perspective. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2019, 38, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, A.L.; Priestley, M.; Tyrrell, K.; Cygan, S.; Newell, C.; Byrom, N.C. University student well-being in the United Kingdom: A scoping review of its conceptualisation and measurement. J. Ment. Health 2021, 30, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelson, J.L. Educational research with real-world data: Reducing selection bias with propensity score analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2013, 18, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, C.; McNeish, S.; McColl, J. The impact of part time employment on students’ health and academic performance: A Scottish perspective. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2005, 29, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Gonzalo, S.; González-Pascual, J.L.; Gil-Del Sol, M.; Esteban-Gonzalo, L. Exploring new tendencies of gender and health in university students. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2021, 24, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, S.; Lichtenstein, G.R.; Safdi, M.A. 5-ASA dose-response: Maximizing efficacy and adherence. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Geertshuis, S.A. Slaves to our emotions: Examining the predictive relationship between emotional well-being and academic outcomes. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.P.; Firman, K. Associations between the wellbeing process and academic outcomes. J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2019, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Psychology (All Years) | English Studies (All Years) | Nursing (1st Years) | International Politics (2nd Years) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention N = 50 | Control N = 25 | p-Value | Intervention N = 11 | Control N = 6 | p-Value | Intervention N = 12 | Control N = 8 | p-Value | Intervention N = 24 | Control N = 17 | p-Value | |

| Year of study, N(%) | 0.06 | 0.002 * | - | - | ||||||||

| 1st year | 15 (30) | 2 (8) | 9 (82) | 0 (0) | 12 (100) | 8 (100) | - | - | ||||

| 2nd year | 24 (48) | 13 (52) | 0 (0) | 3 (50) | - | - | 24 (100) | 16 (100) | ||||

| 3rd year | 11 (22) | 10 (40) | 2 (18) | 3 (50) | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Age (years), N(%) | 0.02 * | 1.00 | 0.51 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 17–20 | 41 (84) | 14 (56) | 9 (90) | 5 (83) | 9 (75) | 4 (57) | 16 (67) | 11 (65) | ||||

| 21–24 | 6 (12) | 8 (32) | 1 (10) | 1 (17) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 7 (29) | 6 (35) | ||||

| 25+ | 2 (4) | 3 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (17) | 3 (43) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Gender, N(%) | 0.26 | 1.00 | 0.61 | 0.03* | ||||||||

| Female | 48 (98) | 23 (92) | 8 (80) | 5 (83) | 11 (92) | 6 (86) | 16 (67) | 5 (29) | ||||

| Male | 1 (2) | 2 (8) | 2 (20) | 1 (17) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 8 (33) | 12 (71) | ||||

| I use another term | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Ethnicity, N(%) | 0.94 | 0.79 | 0.16 | 0.32 | ||||||||

| White British | 10 (20) | 5 (20) | 4 (40) | 2 (33) | 3 (25) | 2 (29) | 8 (33) | 3 (18) | ||||

| Other white background | 12 (25) | 5 (20) | 3 (30) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 2 (29) | 7 (29) | 9 (53) | ||||

| BAME $ | 27 (55) | 15 (60) | 3 (30) | 2 (33) | 9 (75) | 3 (43) | 9 (38) | 5 (29) | ||||

| Prefer not to say | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Part-time job, N(%) | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.01* | ||||||||

| Yes | 11 (22) | 7 (28) | 6 (60) | 1 (17) | 6 (50) | 0 (0) | 12 (50) | 3 (18) | ||||

| No | 38 (78) | 18 (72) | 4 (40) | 5 (83) | 6 (50) | 7 (100) | 12 (50) | 14 (82) | ||||

| Student status, N(%) | 0.20 | 0.46 | 0.37 | 0.52 | ||||||||

| Home (UK) | 24 (49) | 18 (72) | 9 (90) | 4 (68) | 12 (100) | 6 (86) | 12 (50) | 5 (29) | ||||

| EU | 10 (20) | 3 (12) | 1 (10) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 6 (25) | 6 (35) | ||||

| International | 15 (31) | 4 (16) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (25) | 6 (35) | ||||

| Disability status, N(%) | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.52 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Yes | 2 (4) | 21 (84) | 2 (20) | 1 (17) | 1 (8) | 2 (29) | 1 (4) | 1 (6) | ||||

| No | 46 (94) | 4 (16) | 8 (80) | 5 (83) | 11 (92) | 5 (71) | 22 (92) | 15 (88) | ||||

| Prefer not to say | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 1 (6) | ||||

| First in family to study at university, N(%) | 0.17 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.78 | ||||||||

| Yes | 16 (33) | 4 (16) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) | 6 (50) | 2 (29) | 3 (13) | 1 (6) | ||||

| No | 33 (67) | 21 (84) | 7 (70) | 6 (100) | 6 (50) | 5 (71) | 20 (83) | 16 (94) | ||||

| Unsure | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Caring responsibilities, N(%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.31 | 0.29 | ||||||||

| Yes | 3 (6) | 2 (8) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 2 (17) | 3 (43) | 1 (4) | 3 (18) | ||||

| No | 46 (94) | 23 (92) | 9 (90) | 6 (100) | 10 (83) | 4 (57) | 23 (96) | 14 (82) | ||||

| Name | Number of Students Taking Module; Year of Study | Why: Wellbeing Approach | What | Who Provided | How/Where | When and How Much |

| Intervention modules | ||||||

| Psychology: Graduate Attributes | N = 296; All years | Academic-based strategy | Sessions on core study skills, digital literacy, skills for mental wellbeing, communication skills, and building a career. | Senior lecturers and teaching fellows in Psychology department | Online; mixture of synchronous and asynchronous (LinkedIn learning videos) | Two semesters (October 2020–March 2021); 20 sessions |

| English Studies: Skills and Support for your Degree | N = 220; All years | Academic-based strategy | Skills development for degree, career support to improve wellbeing. | Senior lecturers in English department | Online; synchronous | Two semesters (October 2020–March 2021); 22 sessions |

| Nursing: Wellbeing in London | N = 36; 1st years | Five ways to wellbeing | Supports students to engage in the ‘5 ways to wellbeing’ approach: keep moving, invest in relationships, never stop learning, give to others and savour the moment. | Lecturer in Nursing Education | Online; synchronous | One semester (January–March 2021); 6 sessions |

| International Politics: Issues in International Politics | N = 89; 2nd years | Curriculum infusion | Teaches theoretical and empirical content regarding international relations. Sessions are structured around human emotions. | Teaching fellow and graduate teaching assistant | Online; synchronous | One semester (January–March 2021); 10 sessions |

| Control modules | ||||||

| Psychology: Graduate Attributes | N = 348; All years | Less intensive intervention, i.e., same as intervention but attended <4 sessions | Two semesters (October 2020–March 2021); <4 sessions | |||

| English Studies: Skills and Support for your Degree | N = 380; All years | Less intensive intervention, i.e., same as intervention but attended <4 sessions | Two semesters (October 2020–March 2021); <4 sessions | |||

| Nursing: Mental Health in Context | N = 38; 1st years | Did not aim to improve student wellbeing | Teaches students about the multiplicity of mental health presentations, their different management styles, and the ethical issues that surround them. | Lecturer in Nursing Education | Online; synchronous | One semester (January–March 2021); 6 sessions |

| International Politics: Economics of the Public Sector | N = 46; 2nd years | Did not aim to improve student wellbeing | Teaches economic analysis of taxation and spending on the welfare state in the UK. | Reader in Political Economy | Online; synchronous | One semester (January–March 2021); 10 sessions |

| Measure | Number of Items | Scoring | Scores Range from… | What Scores Represent | Example Item | Internal Consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCS* | 12 | 1–7 Strongly disagree to strongly agree | 12 to 84 | Higher scores = higher campus connectedness | There are people at university with whom I feel a close bond. | 0.92 [36] |

| UCLA-6 | 6 | 1–4 Never, rarely, sometimes, often | 6 to 24 | Higher scores = greater loneliness | I lack companionship. | 0.82 [24] |

| SWEMWBS | 7 | 1–5 None of time, rarely, some of time, often, all of time | 7 to 35 | Higher scores = more positive mental wellbeing | I have been feeling optimistic about the future. | 0.84 [37] |

| Flourishing Scale * | 8 | 1–7 Strongly disagree to strongly agree | 8 to 56 | Higher scores = greater sense of flourishing | I lead a purposeful and meaningful life. | 0.89 [38] |

| SC-SF | 12 | 1–5 Almost never to almost always | 12 to 60 | Higher scores = higher self-compassion | I try to be understanding and patient towards those aspects of my personality I do not like. | 0.86 [27] |

| Short Burnout | 3 | 1–6 Strongly disagree to strongly agree | 3 to 18 | Higher scores = higher burnout | I feel burned out from my studies. | Exhaustion and cynicism subscales = 0.66 and 0.79, respectively [28] |

| SISE | 1 | 1–5 Strongly disagree to strongly agree | 1 to 5 | Higher scores = higher self-esteem | I have high self-esteem. | 0.75 [29] |

| R-SPQ-2F: Deep learning approach subscale | 10 | 1–5 Never or only rarely true of me, sometimes true of me, true of me about half the time, frequently true of me, always or almost always true of me | 10 to 50 | Higher scores = greater use of deep learning approach | I find that, at times, studying gives me a feeling of deep personal satisfaction. | 0.73 [35] |

| R-SPQ-2F: Surface learning approach subscale | 10 | 1–5 Never or only rarely true of me, sometimes true of me, true of me about half the time, frequently true of me, always or almost always true of me | 10 to 50 | Higher scores = greater use of surface learning approach | My aim is to pass the course while doing as little work as possible. | 0.64 [35] |

| Psychology | English Studies | Nursing | International Politics | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |||||||||

| N | M(SD) | N | M(SD) | N | M(SD) | N | M(SD) | N | M(SD) | N | M(SD) | N | M(SD) | N | M(SD) | ||

| Wellbeing | Pre | 50 | 21.40 (3.93) | 25 | 20.36 (3.41) | 11 | 19.22 (2.20) | 6 | 19.31 (2.74) | 8 | 19.94 (2.96) | 6 | 20.27 (2.91) | 19 | 19.19 (4.37) | 13 | 21.95 (4.60) |

| Post | 50 | 20.51 (3.87) | 25 | 19.22 (3.35) | 11 | 18.53 (4.62) | 6 | 17.67 (5.83) | 8 | 21.59 (3.42) | 6 | 21.83 (2.80) | 19 | 19.79 (3.06) | 13 | 21.17 (3.96) | |

| Mean difference | −0.89 | −1.14 | −0.69 | −1.64 | 1.65 | 1.56 | −0.60 | −0.78 | |||||||||

| Loneliness | Pre | 50 | 14.46 (4.40) | 25 | 15.00 (5.23) | 11 | 17.64 (3.93) | 6 | 15.33 (4.46) | 8 | 16.25 (3.85) | 6 | 18.33 (3.20) | 19 | 14.42 (3.83) | 13 | 14.46 (4.47) |

| Post | 50 | 14.64 (4.26) | 25 | 16.60 (5.37) | 11 | 16.55 (5.05) | 6 | 16.83 (3.97) | 8 | 15.38 (3.58) | 6 | 14.67 (2.07) | 19 | 13.79 (3.90) | 13 | 13.54 (5.03) | |

| Mean difference | 0.18 | 1.60 | −1.09 | 1.50 | −0.87 | −3.66 | −0.63 | −0.92 | |||||||||

| Self-compassion | Pre | 50 | 35.22 (8.54) | 25 | 33.16 (8.84) | 11 | 28.82 (6.00) | 6 | 30.83 (2.86) | 8 | 30.88 (9.98) | 6 | 35.50 (10.73) | 18 | 36.06 (7.82) | 13 | 38.23 (8.79) |

| Post | 50 | 35.14 (8.24) | 25 | 33.20 (6.65) | 11 | 30.81 (8.36) | 6 | 27.33 (4.23) | 8 | 34.00 (8.82) | 6 | 37.67 (11.13) | 18 | 35.06 (8.34) | 13 | 35.23 (7.01) | |

| Mean difference | −0.08 | 0.04 | 1.99 | −3.50 | 3.12 | 2.17 | −1.00 | −3.00 | |||||||||

| Self-esteem | Pre | 49 | 2.76 (1.11) | 25 | 2.48 (1.05) | 11 | 2.20 (0.79) | 6 | 3.17 (0.98) | 8 | 3.00 (0.93) | 6 | 2.33 (0.82) | 19 | 3.47 (1.17) | 13 | 3.77 (0.83) |

| Post | 49 | 3.04 (1.11) | 25 | 2.60 (1.04) | 11 | 2.00 (0.78) | 6 | 1.83 (0.98) | 8 | 3.13 (1.13) | 6 | 2.33 (0.82) | 19 | 3.53 (1.22) | 13 | 3.85 (0.80) | |

| Mean difference | 0.28 | 0.12 | −2.00 | −1.34 | 0.13 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.83 | |||||||||

| Burnout | Pre | 50 | 9.04 (3.72) | 25 | 10.96 (4.07) | 11 | 11.10 (3.21) | 6 | 11.33 (5.20) | 7 | 11.86 (3.98) | 6 | 9.67 (4.03) | 19 | 11.68 (4.45) | 13 | 11.62 (2.69) |

| Post | 50 | 11.76 (4.17) | 25 | 14.64 (3.09) | 11 | 12.64 (3.04) | 6 | 13.50 (4.59) | 7 | 10.00 (2.24) | 6 | 9.50 (3.83) | 19 | 13.84 (4.23) | 13 | 12.23 (4.87) | |

| Mean difference | 2.72 | 3.68 | 1.54 | 2.17 | −1.86 | −0.17 | 2.16 | 0.61 | |||||||||

| Deep learning approach | Pre | 50 | 32.36 (6.22) | 25 | 28.76 (6.88) | 11 | 31.10 (6.87) | 6 | 28.17 (10.07) | 7 | 27.43 (9.05) | 6 | 35.83 (3.66) | 18 | 29.61 (7.36) | 13 | 33.23 (6.44) |

| Post | 50 | 29.44 (6.82) | 25 | 26.60 (6.80) | 11 | 30.18 (9.13) | 6 | 25.50 (12.28) | 7 | 31.86 (8.60) | 6 | 34.33 (3.61) | 18 | 29.00 (9.27) | 13 | 32.08 (7.06) | |

| Mean difference | −2.92 | −2.16 | −0.92 | −2.67 | 4.43 | −1.5 | −0.61 | −1.15 | |||||||||

| Surface learning approach | Pre | 50 | 23.52 (7.04) | 25 | 23.80 (8.13) | 11 | 21.70 (4.69) | 6 | 23.83 (7.81) | 7 | 26.57 (6.80) | 6 | 18.17 (4.83) | 18 | 26.67 (8.73) | 13 | 24.92 (4.72) |

| Post | 49 | 24.33 (7.70) | 25 | 25.32 (8.15) | 11 | 20.18 (4.85) | 6 | 28.33 (11.72) | 7 | 27.71 (7.39) | 6 | 20.00 (6.99) | 18 | 26.89 (8.13) | 13 | 25.54 (7.48) | |

| Mean difference | 0.81 | 1.52 | −1.52 | 4.50 | 1.14 | 1.83 | 0.22 | 0.62 | |||||||||

| Should universities embed wellbeing in the curriculum? | Pre | 50 | 4.12 (0.69) | 25 | 3.92 (0.86) | 11 | 4.18 (1.17) | 6 | 4.17 (1.17) | 8 | 3.75 (1.17) | 6 | 4.33 (0.52) | 19 | 4.05 (0.91) | 13 | 3.85 (1.46) |

| Post | 50 | 4.04 (1.11) | 25 | 4.08 (0.86) | 11 | 3.91 (1.14) | 6 | 3.83 (1.17) | 8 | 3.88 (1.36) | 6 | 3.83 (1.47) | 19 | 4.21 (1.03) | 13 | 4.00 (1.08) | |

| Mean difference | −0.08 | 0.16 | −0.27 | −0.33 | 0.13 | −0.50 | 0.16 | 0.15 | |||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Upsher, R.; Percy, Z.; Nobili, A.; Foster, J.; Hughes, G.; Byrom, N. A Non-Randomised Controlled Study of Interventions Embedded in the Curriculum to Improve Student Wellbeing at University. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 622. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090622

Upsher R, Percy Z, Nobili A, Foster J, Hughes G, Byrom N. A Non-Randomised Controlled Study of Interventions Embedded in the Curriculum to Improve Student Wellbeing at University. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(9):622. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090622

Chicago/Turabian StyleUpsher, Rebecca, Zephyr Percy, Anna Nobili, Juliet Foster, Gareth Hughes, and Nicola Byrom. 2022. "A Non-Randomised Controlled Study of Interventions Embedded in the Curriculum to Improve Student Wellbeing at University" Education Sciences 12, no. 9: 622. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090622

APA StyleUpsher, R., Percy, Z., Nobili, A., Foster, J., Hughes, G., & Byrom, N. (2022). A Non-Randomised Controlled Study of Interventions Embedded in the Curriculum to Improve Student Wellbeing at University. Education Sciences, 12(9), 622. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090622