1. Introduction

Technological progress, and in particular the wide use of internet and smart phones, has drastically changed the way we provide and receive information, communicate and interact with each other [

1,

2,

3]. Digital and social media, web applications and online forums have entered school reality and have gained teachers’ and parents’ interest appearing as facilitators of their communication [

4] and as tools for straightening their relationships [

5]. The present study makes an effort to contribute to furthering our understanding on the role of social media in parent–teacher relationships, by focusing on school parents’ online groups and investigating Greek teachers’ perceptions concerning them.

The internet has become a place where parents expose their personal life [

1], ask for and give information on parental or children habits [

6] and share their experiences [

3]. The online publishing of the way that parents fulfill their social role or parental obligations, as well as the online exposure of their children’s everyday life, has been described as “sharenting” [

7,

8]. Sharenting, apart from a spontaneous action or momentum need, seems to become a conscious practice and even a common habit of parents of children at every age. Participation in various social media facilitates it [

3] as social media constitute the field in which parenting can be exposed, information about it can be shared and difficulties around it can be overcome through support, advice and empathy from other parents, members of social media groups and thus sharenting communicants.

However, last decade’s changes do not only concern the means and types of communication or the ways and practices of parenting. They also concern family-school and parent-teacher relationships, which are not only affected by technological and web progress, but they are transformed by it in several aspects [

9,

10,

11]. Digital media, the internet and other new technologies conquer step-by-step the communication between school and family [

11]. They gradually replace the face-to-face parent-teacher interaction [

12,

13] and they often emerge as a source of knowledge even more significant than school [

2,

6]. Through the web, teachers tend to inform parents about school events, school program and class activities. Through synchronous and asynchronous web applications teachers increasingly communicate to parents the evaluation of their children’s school performance, they provide the children’s grades, they organize meetings with parents and they share moments of every-day school life more and more systematically than the years before.

Research argues that, the more actively the teacher uses digital media, the more active parents become in doing so too [

14,

15] and that when school management team encourages digital communication with families, most parents respond positively [

10]. Furthermore, as education and school constitute two of the parents’ most searched online topics [

6], one would not exaggerate in proposing that parents have nowadays added one more dimension to their social role. In addition to education’s consumers [

16], teachers’ partners [

17] and school clients [

18] parents have also become school and education digital users.

New advances in technology have irreversibly influenced school education around the globe [

15]. Schools in Greece, and generally in Europe, rely on digital media and the internet to form and update their everyday schedule, to collect and arrange data concerning teachers, pupils and parents, to inform their personnel and to communicate with pupils’ families [

11,

15]. Digital communication with families is considered more efficient, more immediate and more convenient than traditional one [

10,

19] and thus schools are encouraged to adopt it and gradually establish it as their main form of communication with families. Research suggests that teachers are positive to such a development, but also in need of training in digital communication skills [

10,

11,

20,

21], as misunderstandings and conflicts with parents can occur from ambiguous digital messages or inaccurate online comments.

Under this evolution, parent-teacher digital communication and online parental school involvement become topics of great scientific interest. Very limited research, though, deals with this matter [

10,

11,

15] and as for Greek parents and teachers, we did not manage to locate any related studies. Investigation of online parental involvement revealed that parents adopt behaviors similar to offline ones when contacting school and teachers [

14].

Parents tend to perceive school education and communication with teachers as a maternal responsibility [

22], so, compared to fathers, mothers participate more eagerly in digital school platforms and communicate more regularly with teachers via online applications or other digital media [

14,

15]. Research also suggests that in schools where e-communication with families is implemented parents and teachers express positive statements on the use of digital media [

10] and affirm that in some cases parent-teacher partnership is more efficiently promoted when using digital communication [

11]. Finally, few studies focus their interest on the role of socio-economic status of parents in the use of digital media for their children’s education [

23], demonstrating that the wealthy and well-educated parents are in position to better provide for their children.

Realizing that the role that parents play in supporting their children’s school education has become intricately tied to their information technology use and based on the fact that there has been surprisingly very limited work performed related to parents’ online activity concerning schooling [

6,

11,

23], the present study focuses on online groups formed by school parents and investigates teachers’ perceptions about them.

In general, school parents’ online groups (SPOGs) are created in widely known social media, such as Viber, WhatsApp or Messenger, so that even parents who are less familiar with digital communication can have immediate and constant access through their smartphones [

24]. Participants are restricted to parents whose children are in the same classroom. A systematic circulation of school information is realized within a SPOG in absence and ignorance of the teachers and school principals [

24]. So, as with other social media and digital platforms, “the locus of information control shifts from the expert or teacher to the consumer or parent” [

2] (p. 12) and one can support that teachers find themselves not only “weakened”, in a sense that their authority is questioned, but also “expelled” from online discussions about schooling and from digital interactions of school community members.

Thus, realizing that the introduction of digital technologies in school-family communication create a critical turning point in parent-teacher interactions and relationships, the present study aimed to answer the following research questions:

What is the content that teachers attribute to SPOGs?

How do they believe that SPOGs influence their work and their relationships with other school agents?

What are the positive and negative aspects of SPOGs?

2. Materials and Methods

The objective and the research questions of the study dictated the choice of a quantitative approach, as it allows to collect data during a specific time period, to describe the nature of the existing conditions and to identify the general tendency concerning a specific matter [

25,

26,

27]. The questionnaire was selected as the basic instrument for the data collection, since bibliography [

25,

26,

27] describes it as an effective research tool, which is reliable and consistent as it handles numerical metrics and decreases potential bias. The questionnaire provides to the researcher the possibility to collect specific data quickly and efficiently and to the participant the ability to answer with honesty, out of the influence of the researcher [

25].

For the needs of the present research an anonymous closed-ended online questionnaire was created to address the forementioned research questions. The questionnaire was divided in two parts. The first part gathered questions concerning the demographics of the participants and the level of their digital skills (Q. 1–20) and the second part included questions that tried to seize teachers’ perceptions concerning SPOGs (Q. 21–33, 40–42) and their influence on their teaching (Q. 34–39, 43–48) and the relationships with other school members (Q. 49–57). All questions were closed-ended and were followed by five-level or four-level scale responses depending on the question.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 28. Descriptive statistics were implemented for both categorical and qualitative variables of rating scale. Percentage of the overall cases (%), frequency (N), mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) were calculated. Also, chi-square tests were performed, and

p-value was used to describe statistical significance [

27]. The questionnaire’s reliability was tested using Cronbach-a coefficient [

27] and was proven of high internal consistency (0.907). Similarly, all standards were respected to secure the validity of values (e.g., questionnaire created to measure exactly what we wanted to know, choice of a high-quality measurement technique, analysis via a generally approved program, etc.) [

25,

27]. Through a non-probable sampling 246 questionnaires were gathered using convenient sampling, followed by a snowball sampling [

27]. The link for the online questionnaire, which was created in Google Forms, was sent to teachers’ private emails, as well as to school emails and participants were then encouraged to forward it to their colleagues.

The sample was formed as described in

Table 1. The majority of the participants work in primary schools (85%), hold a master’s degree (68.7%) and are between 31 and 45 years old (54.5%). Furthermore, 83.5% of the participants work in a permanent working status in public schools (67.9%) and 61.8% are married. As expected [

28], the majority (78.9%) are women.

3. Results

The results of our statistical analysis are presented in the present chapter. At this point, it is critical to mention that all possible correlations to the independent variables that characterize the sample were tested, but only the ones with significance are going to be addressed bellow. The application of chi-square tests was performed aiming to offer a more in-depth analysis of our collected data and to characterize the differences in teachers’ perceptions that might depend on their social characteristics [

27].

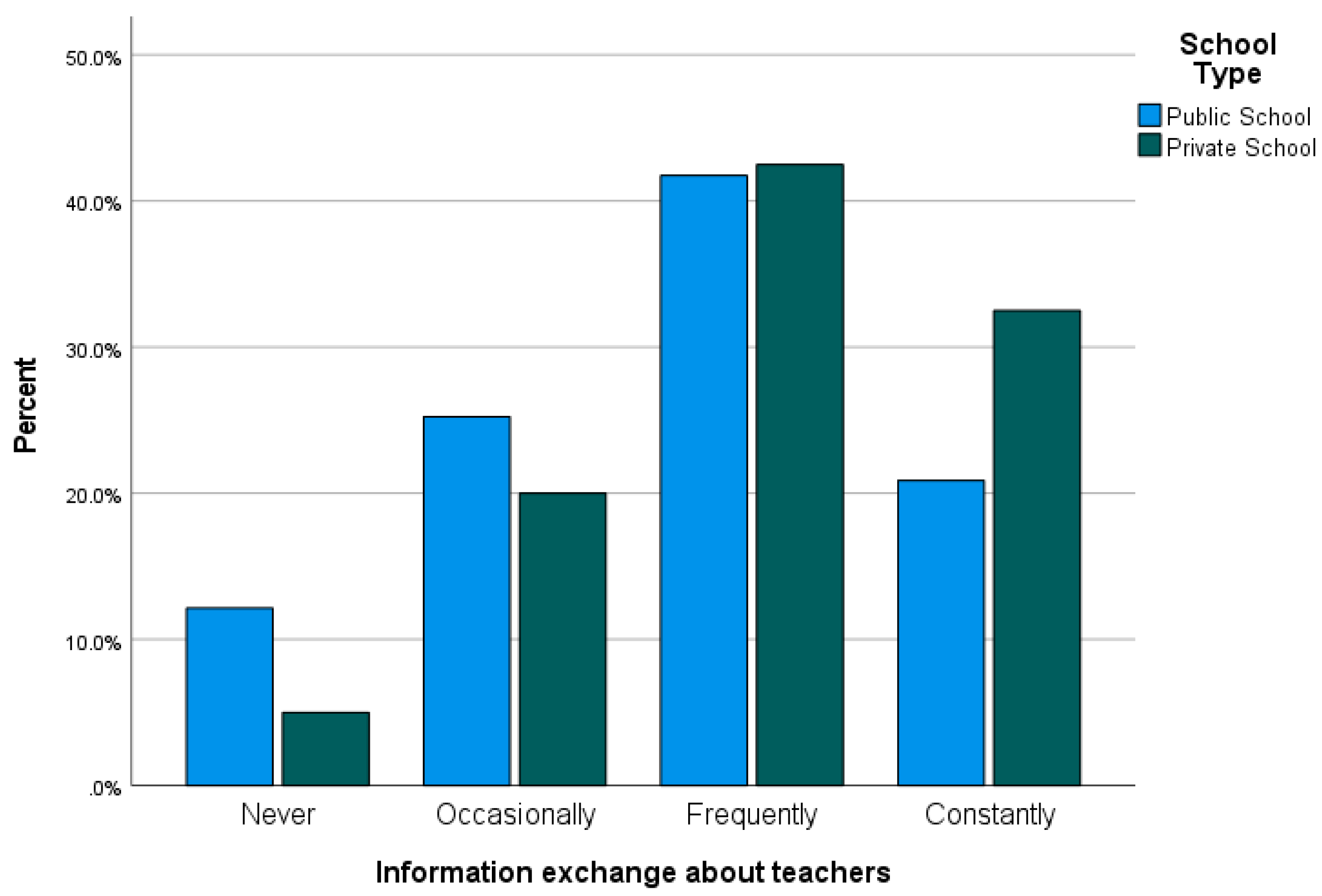

Teachers’ perceptions regarding SPOG content was the first topic of interest of the present study. Requested responses concerned frequency of discussed topics within SPOGs and options ranged from never (1) to constantly (4). Participating teachers seem to believe that parents most frequently share information about school incidents, assigned homework and about what has happened in the classroom during teaching (

Table 2). They also believe that parents frequently share information about teachers within their online group (

Table 2).

A significant differentiation is observed between teachers in private and public schools (x

2 = 3.925, df = 3,

p = 0.05), as the first believe that parents within SPOG exchange comments and information about them on a frequent basis (frequently: 41.5%, constantly: 32.5%), while public school teachers think that this kind of information is rarely discussed within SPOGs (never: 12.1%, constantly: 20.9%) (

Figure 1).

On the other hand, exchange of homework answers and solutions is believed to rarely occur within SPOGs. Similarly, discussions about children school fights and disagreements are not a topic which preoccupies parental discussions in their online group according to our participants (

Table 3).

Concerning parents’ complaints and negative comments regarding teachers’ behaviors, teaching or homework assignments, participants seem to have a rather vague opinion and most participants believe that parents only occasionally complain in SPOGs, as the following table shows (

Table 4).

On the contrary, it seems clear to them that parents rarely praise teachers in their online discussions, while most of them affirm that parents only occasionally express their satisfaction about school function or teaching (

Table 5).

The questionnaire also investigated teachers’ perceptions regarding the influence that parental online group discussions exert to their work. More specifically, responses were grouped in a five-level agreement-disagreement scale concerning SPOGs influence to the teachers’ teaching, their communication with parents, their professionalism and the pedagogical aspect of their school activity. As it is shown below, teachers strongly believe that SPOGs do not affect their teaching, nor their professional profile or their daily school activities. The importance of SPOGs to their work is minor or even inexistent according to their answers (

Table 6 and

Table 7).

A significant differentiation based on gender is though observed. Parents seem to inform male teachers more frequently than female ones (x

2 = 8.860, df = 3,

p = 0.02) about SPOG discussion topics (

Figure 2). Furthermore, they want to discuss issues raised within SPOGs with male teachers more than they do with female teachers (x

2 = 8.530, df = 3,

p = 0.009) (

Figure 3) and they expect from them to deal with and resolve those issues (x

2 = 6.951, df = 3,

p = 0.01) (

Figure 4).

Similarly to previous topics, participants provided more neutral responses when asked about the SPOG’s impact to their relationships with other school community members (

Table 8).

However, age appears to be an important factor concerning their responses to the question of whether SPOGs create problems to teacher–principal relationship (x

2 = 21.062, df = 8,

p = 0.01), with teachers of 31–45 years old affirming their disagreement to the proposition (41.1%) (

Figure 5).

Gender also influences participants’ responses concerning the negative impact of SPOGs to relationships among colleagues (x

2 = 10.582, df = 4,

p = 0.02) (

Figure 6). Women state their disagreement to that proposition (54.1%), while men believe that SPOGs can harm their relationships with colleagues (33.7%).

The existence of SPOGs began a few years after the dominance of smartphones, so at this point teachers have formed their perceptions regarding their positive and negative aspects. Participants in the present research think that information that is circulated within SPOGs and concerns schooling and teachers is most times distorted (62%). Fake news can be shared on a frequent, even everyday basis, all along with inaccurate information and gossips about teachers (

Table 9).

Furthermore, most teachers affirm that discussions in SPOGs frequently create tensions to parents’ relationships (41.3%), while most importantly topics discussed in their online groups become more serious and more stressed out. Also, teachers identify the intention of certain parents to create problems and tensions among school community members (

Table 10).

A correlation was found between public and private school teachers (x

2 = 4.539, df = 4,

p = 0.04), as the latter believe that the more parents discuss in SPOGs, the more problems are created (67.5%) (

Figure 7).

Finally, parental interventionism is positively related to SPOGs (

Table 11). Teachers affirm that SPOG discussions favor parental interventionism and facilitate parental hyper-information. So, according to teachers, parents are not always able to distinguish between real and distorted information and they should be more skeptical and suspicious of SPOG information.

On the other hand, teachers refer to positive aspects of SPOG function, while declaring to be mostly neutral to the fact that parents of their classroom have created and participate in one (neither like, nor dislike: 63%). However, they recognize that SPOGs provide parents with useful information concerning schooling and learning and can strengthen their relationships (

Table 12).

Gender seems to play an important role in the recognition of positive aspects of SPOGs. Men agree more than women that SPOGs positively influence parents (x

2= 7.248, df = 4,

p = 0.05) (

Figure 8) and support children’s learning (x

2= 5.272, df = 4,

p = 0.05) (

Figure 9), while women believe more than men that SPOGs reinforce parents’ relationships (x

2= 5.239, df = 4,

p = 0.05) (

Figure 10).

4. Discussion

As online communication has entered people’s everyday life, it is crucial to study its insertion in education and in school members’ interactions. The present study took the first step in doing so by examining Greek teachers’ perceptions regarding school parents’ online communication and sharenting. The interest focused on school parents’ online groups (SPOGs), which are groups created in social media by parents with children in the same classroom and which are restricted to specific, invited members, i.e., the classroom parents. The aim of the study was to seize teachers’ perceptions regarding the topics discussed in these groups, the influence that SPOGs have to teachers’ work and to intraschool relationships and the negative and positive aspects that teachers attribute to SPOG function.

Considering that SPOGs have been created just in the recent years, following the extended use of smartphones, which are the main device that parents use to access these groups, research on the topic appears extremely limited. Thus, connecting our results to previous studies proved to be a difficult task, as SPOGs have not yet been studied thoroughly. This fact also became obvious while managing the data and analyzing teachers’ responses.

Most of participants’ answers demonstrate their lack of familiarity with SPOGs, as well as their unformed opinions on the subject. So, teachers adopted a neutral attitude to many of the questionnaire’s questions by choosing “neither agree, nor disagree” option. Overcoming the fact that SPOGs constitute a new parental practice [

24], one can diagnose through teachers’ answers that they demonstrate a minimum interest in this parental activity. In line with previous research [

29,

30], observed teachers’ distancing can be interpreted as revealing their belief in separate parent-teacher responsibilities, roles and activities.

When asked about SPOG main scope, teachers state that this is the circulation of information regarding class incidents, school events, homework, daily school life, teachers and teaching. They perceive SPOGs as informative mostly for groups and they undermine their supportive role. Yet, they characterize information shared within SPOGs as occasionally fake, frequently distorted and constantly exaggerating. This fact, also observed in other social media forums and groups [

3,

31,

32], contributes to parents’ misconception, stimulates parent-teacher alienation and encourages misunderstandings among them.

In accordance with that assumption, participants support that SPOGs encourage parents’ interventionism and inflate discussed school problems, as it is already referred to recent research [

24], especially as male teachers are being more informed by parents about tensions within SPOGs than female teachers and are more eagerly asked to resolve emerging problems. However, even under these circumstances, teachers affirm that SPOG discussions do not influence their work or their relationship with other school members. In order to explain this fact one can rely on previous research [

29,

30] supporting that teachers assign parents a role that is distant from schooling. They do not perceive them as partners and thus they do not acknowledge them the ability to affect their teaching, their professionalism or their intraschool relations.

Complaints seem to appear within SPOG discussions only occasionally, according to teachers, while even more rarely the teachers or the school function are praised within SPOGs. It is however surprising that teachers suggest that parents discuss, share information and express themselves in SPOGs about school matters, without complaining or praising teachers or school at all. In an attempt to interpret this statement, one could support that teachers do not always become recipients of parental complaints or praising, because parents mostly share these comments with principles, who act as information filtering intermediates to teachers [

22].

Finally, participating teachers recognize some positive aspects of SPOG function for school parents. As teachers state, through SPOGs parents get to know each other, parental relationships become stronger and some useful information about schooling is circulated. No positive aspects regarding school-family or teachers-pupils’ relationships were identified by teachers, but as research states good relationships among parents promote pupils’ well-being and school integration [

30].

At this point research limitations should be mentioned and directions for future studies should be provided. At first, despite its originality, the present paper examines SPOG content, influence and aspects through the teachers’ lens of reality. So, in order to obtain a more objective view of the studied phenomenon, further research needs to be performed. An examination of parents’ intragroup exchanged messages is mandatory, as it can provide a detailed description of SPOG content. Also, aiming to fully understand SPOG function and importance, parents’ perceptions and attitudes towards these groups should be thoroughly investigated. Such a study could allow to compare parents’ and teachers’ perceptions regarding SPOGs and capture their similarities and differences.

Another limitation that should be taken into consideration concerns the sample used for this paper. As mentioned above, Greek teachers demonstrate an unwillingness to participate in research. So, our sample, although coming from all over Greece and meeting all statistical requirements, could not be completely representative of the population of primary education teachers. Kindergarten teachers represented only 13.6% of the study’s sample, while preschool education is mandatory since 2010 and thus preschool teachers’ population is proportionally close to that of primary school teachers. Moreover, Greek schools employ a significant number of educators specialized to teaching foreign languages, physical education and arts. The representation of these specialties in our sample is limited and thus one cannot be sure if the current results fully reflect their perceptions. Therefore, the expansion of the present study in school’s specialized personnel is suggested. Finally, it could be interesting to examine if similar perceptions concerning SPOGs are shared among teachers of secondary education.