Abstract

Amid the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, this study conducts a rigorous analysis of the online learning landscape within higher education. It scrutinizes the manifold issues that emerged during the era of quarantine restrictions, investigating the perspectives and experiences of students and academic staff in this transformative educational paradigm. Employing a comprehensive suite of research methodologies, including content analysis, observation, comparative analysis, questionnaires, correlation studies, and statistical and graphical methods, this research unearths the substantial challenges faced by participants in online learning. It meticulously evaluates the advantages and limitations of this pedagogical shift during the pandemic, probing into satisfaction levels regarding the quality of online instruction and the psychological aspects of adapting to new learning environments. Moreover, this study offers practical recommendations to address the identified challenges and proposes solutions. The findings serve as invaluable insights for higher education management, particularly within the framework of quality assurance, equipping administrators with the requisite tools and strategies to confront the extraordinary challenges that have arisen in contemporary higher education. These lessons gleaned from the crucible of the pandemic’s trials also hold a unique promise. The results of this research are not confined to a singular crisis but carry a profound implication: the effective application of online learning, even under the most arduous conditions. These ‘pandemic lessons’ become the guiding light for resilient education in the face of any adversity.

1. Introduction

In today’s world, the use of information and communication technologies has radically changed the possibilities of teaching and learning. When the COVID-19 pandemic paused face-to-face learning, online learning became the most available form in higher education. The current situation in the world has clearly demonstrated the active transition from traditional teaching methods through lectures, seminars, laboratory works, and consultations to online education.

Online learning has become one of the forms of learning that has emerged, is improving with the development of Internet technologies, and has clear characteristics, principles, and methods. Until recently, online learning was aimed mainly at adults or students who sought to improve and deepen their knowledge, skills, and abilities in a particular field. The principles of the application of online learning are in the process of development, and its features have become serious challenges for the higher education system. It is worth noting that there are a number of issues that are related to the use of online learning and need to be studied in detail.

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, thousands of higher education institutions around the world were forced to close their doors to visitors and switch from traditional teaching methods to online learning. Students as well as research and teaching staff had to move very quickly to telecommunication technologies using online courses, platforms, digital textbooks, and so on. Today, most online learning users are in the United States and Canada. Among European countries, the leaders are Germany, France, Great Britain, Finland, and Estonia [1,2].

It was predicted that the global online learning market would exceed $243 billion by 2022 [3] and it is slated to hit $475 billion by the end of 2030 with a CAGR of nearly 9.1% between 2023 and 2030 [4]. It should be noted that a significant number of research and teaching staff showed a willingness to support the use of online learning as opposed to traditional teaching methods. According to [3], about 65% of surveyed teachers supported the use of open educational resources in teaching, and 63% expressed support for the education system based on the competencies.

As a result of the COVID-19 outbreak, the use of online learning was accelerated, as evidenced by the research of many scientists [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. However, the world experience shows that there are a number of issues that need to be addressed and researched in online learning.

In this regard, it is important to study the attitude of students as well as research and teaching staff to online learning, identify the advantages and disadvantages of this form of education in the period of COVID-19, and develop proposals that will help management staff of higher education institutions to respond effectively to the modern challenges and improve the provision of quality educational services in this difficult period for all of us.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents some basic definitions and considerations, including the influence of COVID-19 on the education in the world and Ukraine, the main problems that students face within online learning, and some benefits of online education. Section 3 informs that the study was performed to determine the perceptions of the positive and negative aspects of online learning by students and teachers, identify the strengths and weaknesses of online education as well as the benefits and challenges of online learning from the perspective of students and teachers, and examine their willingness to continue online learning in case of further severe quarantine restrictions. Section 4 comprises research results, their analysis and discussion, including some affirmations and comparison with other research findings. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Basic Definitions and Considerations

The situation with the spread of COVID-19 has posed a number of challenges to humanity that need to be addressed quickly and effectively in the shortest possible time. The COVID-19 pandemic has become a turning point, changing approaches in many areas of socio-economic life. One such area is higher education. The situation with COVID-19 clearly shows that without online learning, modern education seems impossible.

At the same time, the abrupt closure of higher education institutions due to quarantine restrictions has created a number of issues in the technical support and psychological perception of the need to move from traditional to distance learning. In such a difficult situation, only those higher education institutions able to successfully overcome modern challenges, where conditions will be created for rapid adaptation in such conditions, in particular the transition from traditional to alternative models of educational services, will be successful. One such model is online learning.

Rapid scientific and technological progress in the field of Internet technologies through the introduction of modern means of communication has allowed movement to a new level of knowledge and skills in the higher education sphere. In particular, it is possible to better adapt to modern conditions through online learning. When, in the spring of 2020, higher education institutions had to switch to online learning in a relatively short time, many said that the future finally arrived, and online education was becoming the norm. However, several months have passed and students and teachers are saying more and more often that it is necessary to return to traditional methods, as during the pandemic online education demonstrated all its limitations and weaknesses.

Before proceeding to the analysis of the main issues related to online learning in the higher education sphere during the quarantine restrictions related to COVID-19, it is necessary to provide some clarifications on the main definitions related to this study.

In particular, according to the UNESCO-UNEVOC International Center for Technical and Vocational Education and Training, online learning is the learning through information and communication technologies to improve distance education, implement open and accessible learning policies, and create more flexible learning activities and the possibility of using such technologies by higher education institutions [28].

M. Rosenberg states that online learning involves primarily the use of Internet technologies to ensure the effectiveness of knowledge acquisition and is based on three key principles:

- The work is carried out in the Internet network;

- The delivery of educational content to the end user is carried out using a computer using Internet technology;

- The system focuses on a broader view of learning [29].

According to E. Rosette, online learning is the learning that takes place using a computer or server connected to the World Wide Web. She also notes that the online learning process takes place in whole or in part through electronic equipment and software [30].

K. Adrich defines online learning as a broad combination of processes, content, and infrastructure using computers and networks to improve the value chain of learning, including provisioning and management. Its application is aimed at reducing management costs, while increasing access to the latest learning technologies [31].

T. Bates notes that online learning is a vector for students in the new paradigm of education and contributes to the development of their skills and abilities for further lifelong learning [32]. V. Eurissen, Head of IBM Management Development Solutions, explains online learning as the process of using innovative technologies and learning models to provide people with new skills, abilities, and access to knowledge [33].

Online learning is a general term that describes learning conducted on a computer, usually connected to a network, which allows a student to learn almost anytime, anywhere. This is not like any other form of education. It is generally accepted that e-learning can be as complete and valuable as traditional or even more, explains N. Sawhey [34].

In our opinion, online learning is a learning process carried out with the help of IT technologies in order to provide all participants in the learning process opportunities to transfer and acquire knowledge, as well as the acquisition of skills and abilities that meet modern life requirements.

2.1. Influence of COVID-19 on the Education in the World

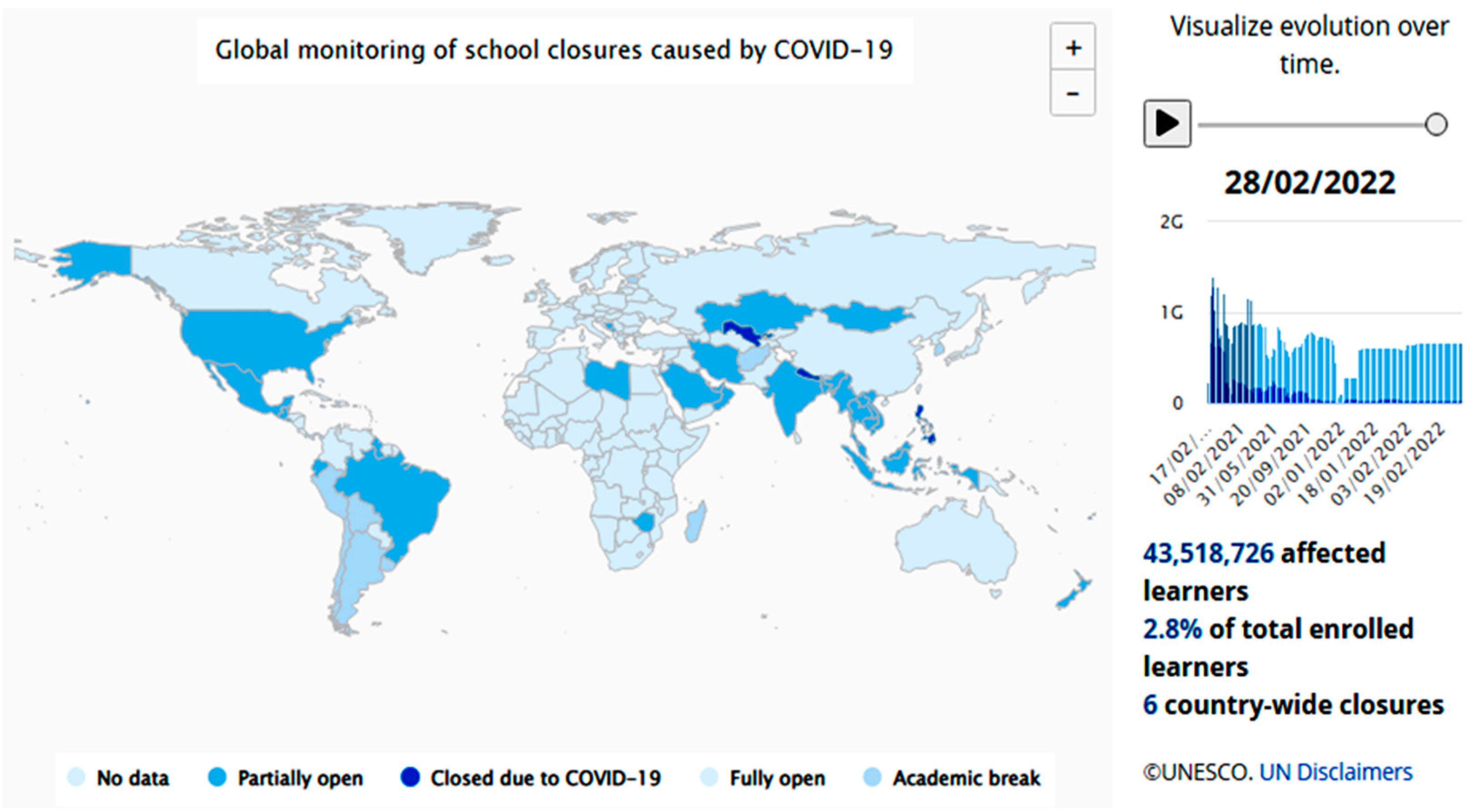

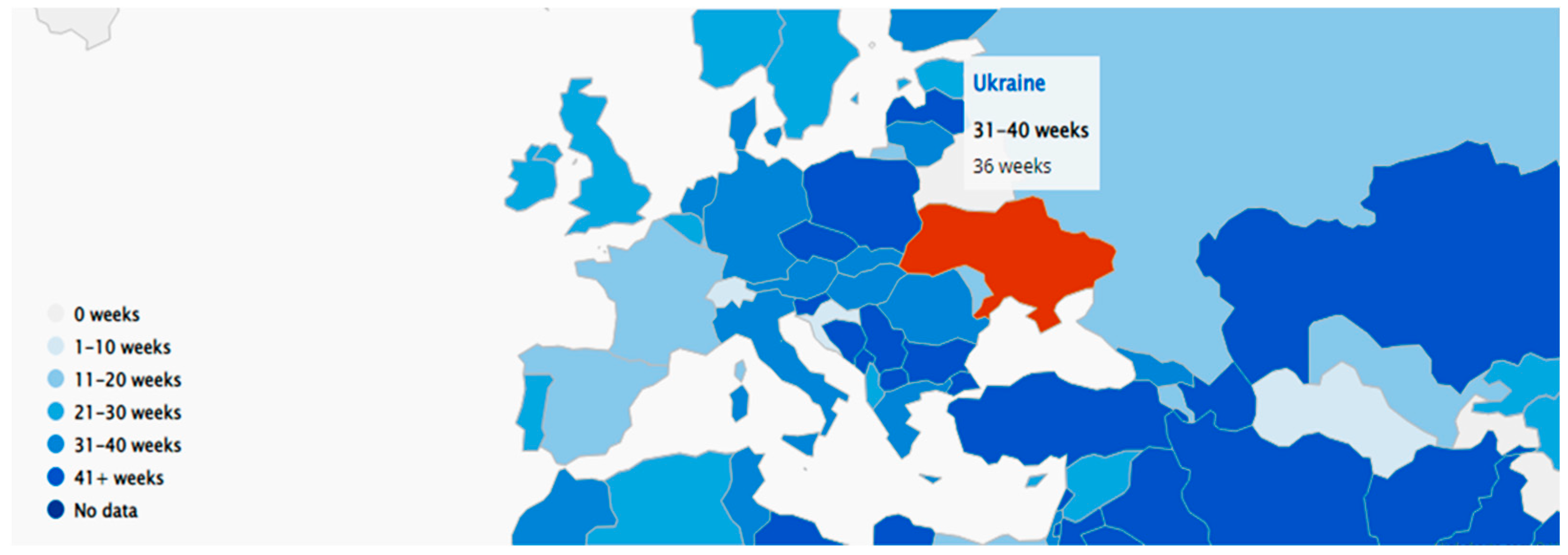

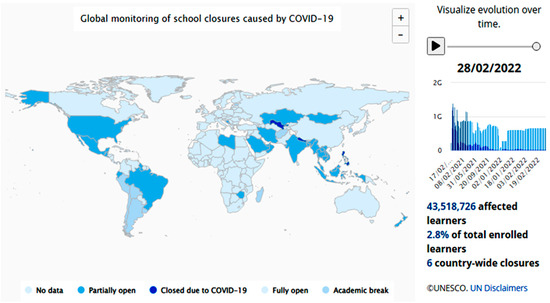

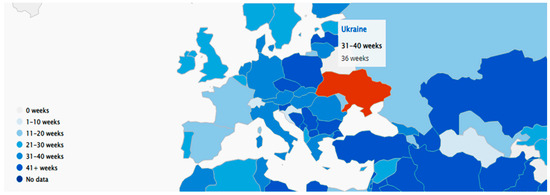

According to UNESCO, as of the end of April 2021, more than 1.7 billion students and schoolchildren worldwide were not attending educational institutions due to their temporary closure by governments in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Today, according to the latest UNESCO data, almost 900 million students, more than half of the world’s student population, face serious barriers to learning. Data on the situation with school attendance and decisions on online learning opportunities during this period are updated daily [35].

Figure 1.

Countries that closed educational institutions due to the COVID-19 pandemic as of 28 February 2022 (figures correspond to the number of students enrolled in pre-school, primary, lower secondary and upper secondary education [ISCED levels 0 to 3], and higher education [levels 5–8 to ISCED]) [36].

Figure 2.

Total duration of the closure of educational institutions in Ukraine (the red colour shows the analysed area) [36].

UNICEF research indicates that more than 460 million students at different levels of education worldwide cannot be enrolled in online learning programs, especially in low-income and rural areas, because they simply do not have access to the necessary facilities or infrastructure [37].

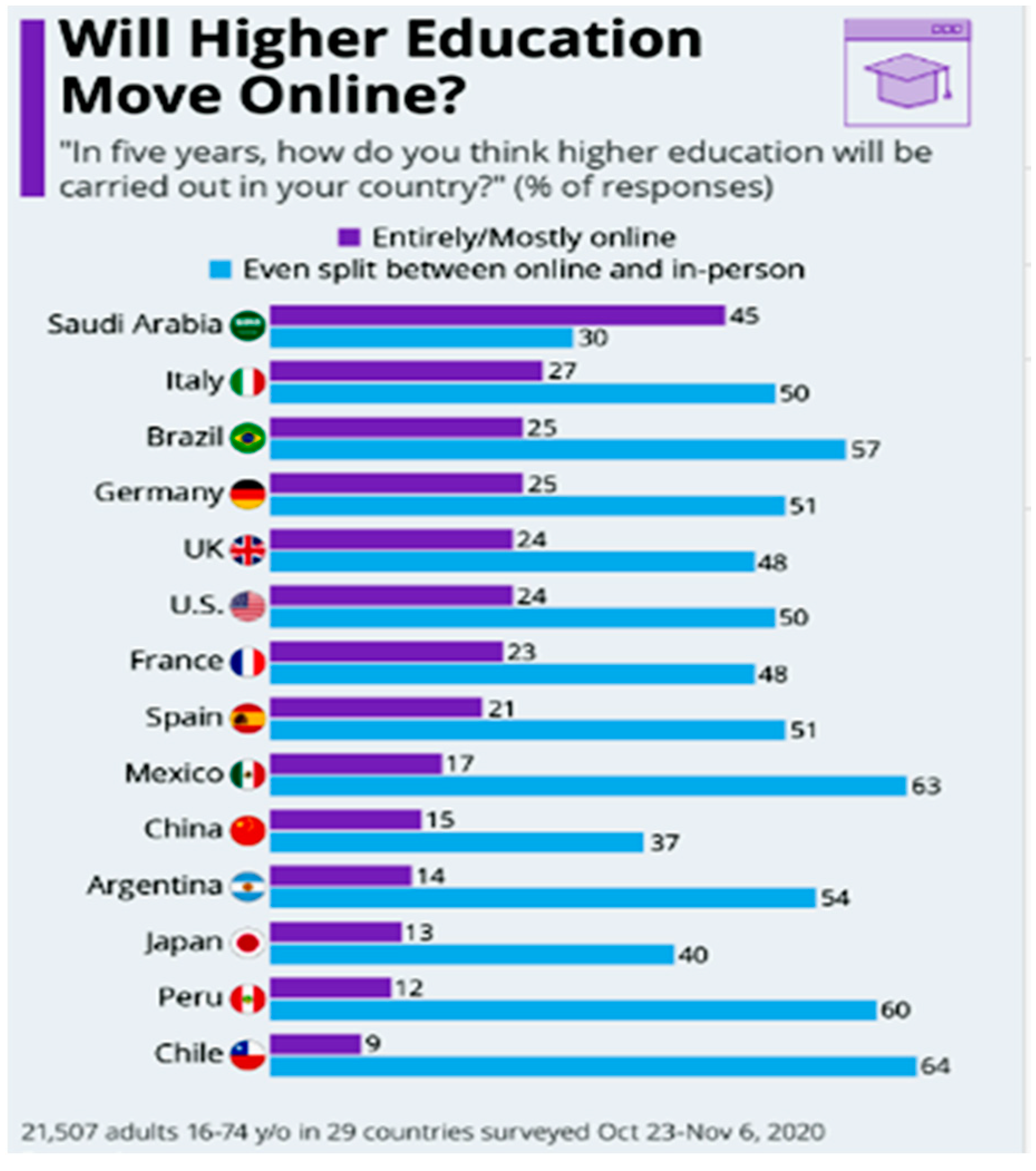

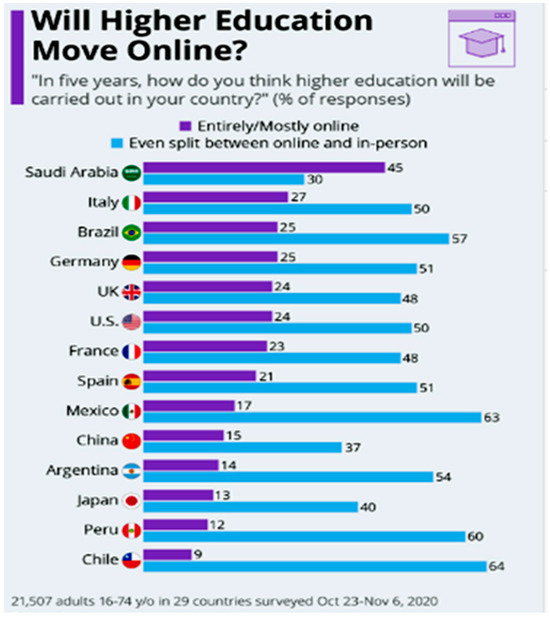

A survey conducted by the research and consulting company Ipsos [38] asked students from 29 countries the question: “How do you think higher education in your country will be carried out in five years?” In total, 23% of respondents believe that higher education in their country will be provided in full or in the vast majority online within five years, and 49% believe that online learning and traditional forms of education will occupy the same part in higher education (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The students’ answers to the question: “How do you think higher education in your country will be carried out in five years?” [38,39].

2.2. The Main Problems That Students Face during Online Learning

A study [40] notes that the population of low-income countries use the least online platforms (64%) and instead use the opportunities of television (92%) and radio (93%). At the same time, the population of higher income countries use online platforms the most (95%), using television (63%) and radio the least (22%). Among the 29 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean analysed in 2020, the most frequently used was online learning implemented by 26 countries in the region. In the survey, only 27% of low-income countries said that learning through television was effective. About 15% of students in Western Europe and North America do not have Internet access, compared to almost 80% in Africa. Loss of quality learning opportunities can reduce the quality of learning for students around the world and increase the number of low-achieving students due to unsatisfactory learning conditions.

In June 2020, a survey was conducted among the management of colleges and universities, in which they expressed different views on the success of online learning implemented in their educational institutions. Namely, 55% of respondents believe that they managed to achieve high academic standards, and 47% said that the measures they have taken were successful in training of less experienced teachers [40].

The study also found that during the 2020 pandemic, students who were forced to study their courses online faced a number of challenges, including:

- Problems with Internet connection, which often prevented them from fully participating in the courses—16% of respondents.

- Hardware/software problems that sometimes affected their participation and attendance—23% of students, with 8% indicating that this happened often.

- The main problem is finding a quiet place to work on the Internet—20% of students surveyed.

- Staying motivated when doing term papers on the Internet—42% of students, and 37% said it was a minor problem.

- 79% of students used a laptop to access their courses, 15% used a desktop computer, and 5% used smartphones or tablets.

- 10% said they should share the device with other users, and 3% said the device they used was provided to them by their school [40].

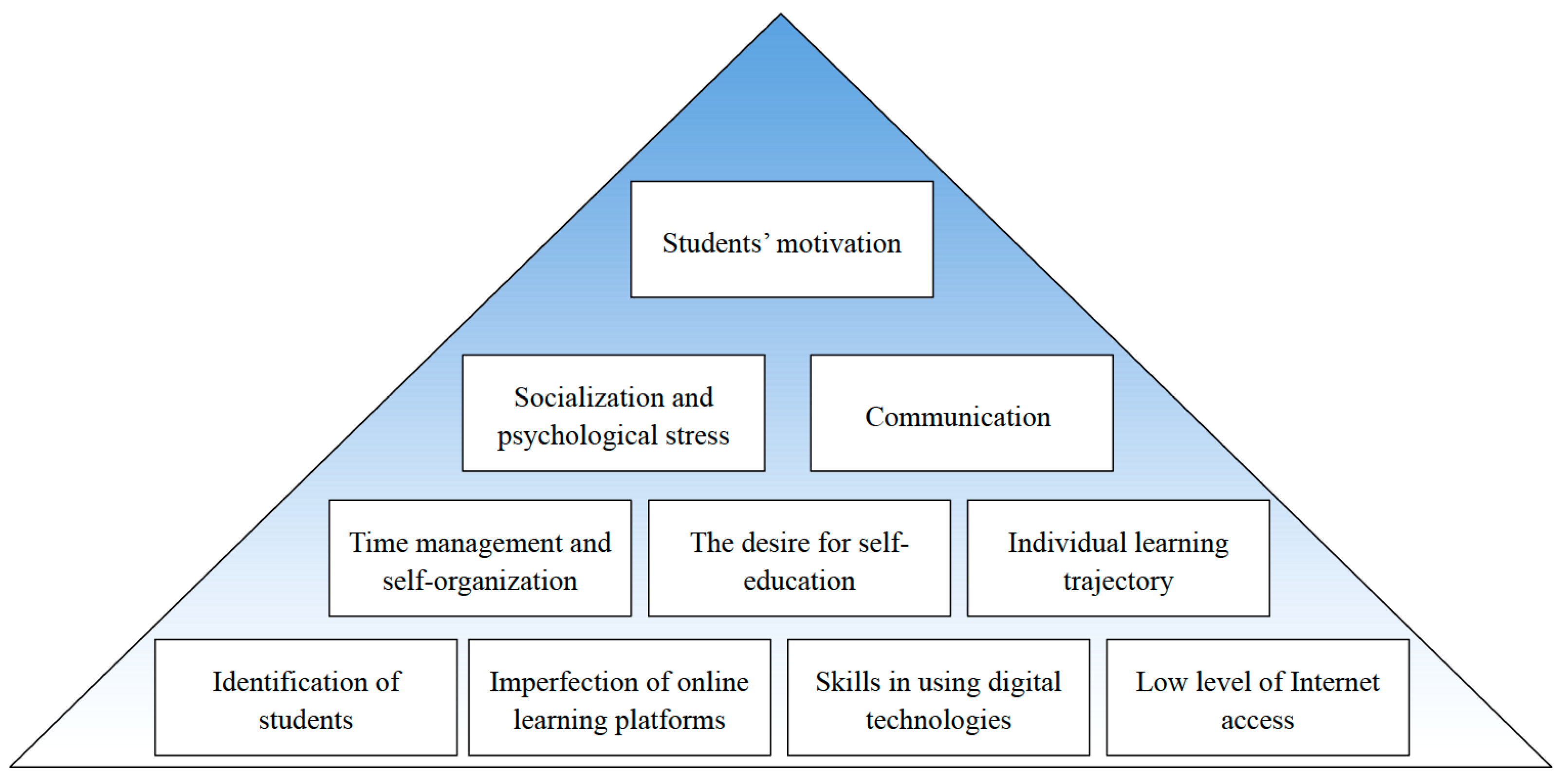

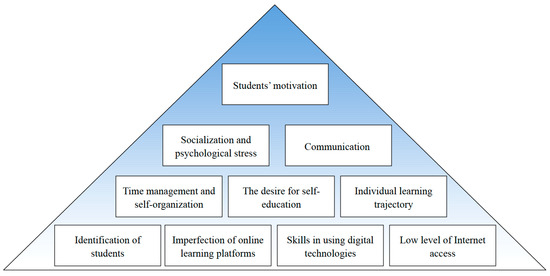

Analysing the work of many scientists from around the world, in particular [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,41,42], we can identify the main issues faced by students and teachers during online learning. For clarity, we present them graphically (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The main factors impacted students and teachers during online learning.

1. Motivation of students is one of the main problems of modern education, and in the conditions of online learning, it becomes even more relevant because constant control by teachers is impossible. Therefore, the situation requires students to independently understand the motivation to learn.

2. Socialization and psychological stress in such conditions becomes a new challenge, as students face many threats to learning: illness, poverty, death of loved ones, information pressure, and so on. In addition, it has been proven that students learn and absorb information better through live communication with peers than in front of a computer. University life helps students socially; they become more independent and confident, learning to work in a team and distribute their time.

3. Communication in the learning process is an extremely important factor. As noted above, in the context of live communication, which took place in traditional learning, there is a constant verbal and nonverbal communication between students, as well as between teachers and students. During online learning, the communication aspect is significantly reduced, which negatively affects the formation of important social communication and cooperative skills.

4. Time management and self-organization. Clear timing is an important aspect of effective learning. During the period of quarantine restrictions, students and teachers faced the problem of allocating time for quality preparation and timely completion of tasks. In the context of online learning, many students find it difficult to organize themselves to work without being distracted by external factors. As a result, both students and faculty have to spend much more time fulfilling their responsibilities.

5. The desire for self-education. Unfortunately, a small percentage of students have a desire for self-education. However, online education requires the student to master the majority of the study material independently. Therefore, teachers face the issue of effective motivation, organization, and control of independent work of students.

6. An individual learning trajectory is one of the main advantages and principles of online learning, i.e., the ability for each student to independently choose the pace of learning as well as time of classes and tasks. In modern conditions, it is rather difficult to carry out in the organizational plan as teachers’ workloads have increased several fold, including emotional pressure.

7. Identification of students. Many teachers have faced the problem of so-called “black rectangles”, when students simply do not turn on the camera during the lesson. Under such conditions, this can lead to falsification of learning outcomes, i.e., performing tasks or providing answers by another person, in some cases.

8. Imperfections of online learning platforms. Nowadays, there are many online services through which training can be performed. However, they all have certain disadvantages and require some time, both from teachers and students, to master them. In addition, each teacher uses the platform that is most convenient and understandable to him/her, which causes dissatisfaction among students, because they have to install and master all these online services, distracting from the learning process.

9. Skills in using digital technologies. Especially for teachers, this problem is complicated by the fact that they need not only to master new programs, online services, and platforms, but also to change their own years-old teaching methods as well as find and apply new methods and forms to achieve mandatory learning outcomes. Students are quite active in the use of digital technologies; however, they also often face certain problems at work but quickly solve them.

10. Low level of Internet access. This is still an acute problem, especially in small towns and villages. The poor quality or lack of internet communication has become a serious obstacle to the provision of quality educational services and needs to be addressed immediately because such a situation can lead to an even greater socio-economic gap between different segments of the population.

Experts from the World Economic Forum in their report [43] note that online learning allows one to get more information and do everything much faster, which means that changes that have been implemented in education because of COVID-19 can be maintained after the pandemic.

Professor R. Ellison from Oxford University disagrees with them, arguing that the purpose of education is to learn to think critically, to analyse, and to question facts and opinions, including one’s own. However, online learning, in his opinion, does not allow a student to achieve this because it is an artificial environment where it is impossible to create the atmosphere of live communication, where students can communicate, make friends, discuss, express their own opinions and so on. In his opinion, a person is a social being, he/she learns and masters information better during ordinary communication, rather than in front of a computer [44].

For many students, the value of university education is not just in getting a qualification. Almost 60% of students and graduates surveyed said that university life helped them socially, they became more independent and confident and learned to work in a team and distribute their time.

2.3. The Benefits of Online Education

Professor R. Ellison argues that online learning is not a new model of education, but simply a fallback option that is used until the situation with the coronavirus in the world stabilizes. However, he acknowledges some advantages of the current situation. In particular, virtual learning helps to create a more open educational environment. Specifically, the more programs that become virtually available, the better it is for students with special needs. In addition, well-known guest lecturers, whom universities invited to speak to students, are more willing to agree to give their lectures without leaving home [44].

Students have to some extent found it easier to communicate with teachers. For example, in the past, students could very rarely “disturb” lecturers during vacations. Now, it has become more acceptable. What research and teaching staff think about that, many of whom spend more time on research during the holidays, is another matter. Nevertheless, for some students, the virtual environment has opened up new opportunities.

Professor R. Ellison notes that easier access to the teacher via the Internet is especially important for international students who went home during the pandemic, and teachers will act as assistants in the future. They will not just pass information by standing in front of students sitting at desks, but will guide students, give them the opportunity to try different teaching methods, and intervene when help is needed [44].

Dr. A. Barutsis, a researcher at the Institute for Educational Research at Griffith University (Australia), says there are many things in education that promote or encourage certain outcomes, which can be considered as successful learning. Some are positive and productive; others are less effective. The use of technology in learning at different times and in different situations can be both. However, there are four key factors that can be considered positive when using technology in learning:

- Availability: the availability of a sufficient number of digital technologies.

- Time and skills: teachers should have enough time to be able to develop and improve their knowledge, skills, and ability to use modern educational technologies.

- Perception: the use of modern gadgets in online learning should be seen as a natural aspect of the learning process, not just a distraction.

- Learning space: the use of modern technologies, in particular online, is a positive factor in learning because today, for most students, they have become the only available tools in the education system and can be used almost without restrictions anywhere and anytime [45].

3. Survey Design and Results

3.1. Survey Design

In this study, the following research questions were addressed:

- -

- What is the perception of the positive and negative aspects of online learning during COVID-19?

- -

- What is the level of satisfaction with the organization of online learning at the university during COVID-19?

- -

- How ready are students and teachers to continue online learning?

- -

- What challenges did students and faculty face in online learning during COVID-19?

- -

- What format of education better promotes the development of knowledge, skills, and social skills according to students and teachers?

- -

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of online learning during COVID-19 according to students and teachers?

The data were collected online using the Google Forms. Following approval by the Chernihiv Polytechnic National University’s Higher Education Quality Systems Management Division, the questionnaire was distributed through communication channels. Students and faculty questionnaires were available to all full-time students and all faculties, including part-time workers. Invitations to take the survey and the link to the questionnaire were distributed in Telegram chats of all full-time academic groups. Invitations to take the survey and the link to the questionnaire of teachers were distributed in Viber chats of departments.

Respondents included students and teachers of Chernihiv Polytechnic National University. The survey was answered by 1323 full-time students (of whom 93.9% were bachelor’s degree students and 6.1% were master’s degree students) and 110 research and teaching staff (of whom 61.8% had more than 10 years of teaching experience, 23.6% had from 5 to 10 years, and 14.6% had up to 5 years).

Based on the analysis of the scientific literature, taking into account the research using the tool for measuring students’ perceptions of quality online classes [45], the authors developed non-standardized questionnaires to collect data, which were separately for students and teachers. The questionnaires included questions that correlate to the research questions.

In this study, we identified the attitudes of students and teachers regarding online learning after six months of quarantine restrictions. At this timepoint, the participants of the educational process have already passed the first stage of online learning during the first stage of quarantine restrictions with the subsequent gradual transition to mixed mode and return to online education due to the second lockdown in Ukraine.

3.2. Results

The aim of the study was to determine the perceptions of the positive and negative aspects of online learning by students and teachers, identify the strengths and weaknesses of online education, determine the benefits and challenges of online learning from the perspective of students and teachers, and examine their willingness to continue online learning in case of further severe quarantine restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The results of the survey (the sum of percentages is not equal to 100, as the respondents chose all the options that satisfy them) show the attitude of students and teachers to online learning (what they like and do not like in this format), the level of satisfaction with the format of distance learning at the university, the challenges faced by students and teachers during online learning under quarantine restrictions, and the priority forms of further education according to students and teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, students and teachers identify the advantages and disadvantages of online learning. The answers are given in ranked order from the option chosen by the largest number of respondents to the smallest. Table 1 shows 5 priority areas for a positive perception of online education from the standpoint of students and teachers.

Table 1.

Top 5 positive aspects of online learning, according to students and teachers.

Table 2 shows 5 priority areas for negative perception of online education from the standpoint of students and teachers.

Table 2.

Top 5 negative aspects of online learning, according to students and teachers.

Among the challenges that students faced during online learning, the answers were distributed as follows:

- lack of continuous access to the Internet (36.4%);

- many difficulties during online learning (34.9%);

- inconvenience in using the university platform for distance education (28.4%);

- inconvenience in using other platforms for online lectures (28.4%);

- impossibility of regular communication with the teacher (17.7%).

As for teachers, the biggest difficulties in online learning for them are related to the following:

- passiveness of students during classes (noted by 60.9% of respondents);

- lack of students connected (55.5%);

- lack of a continuous Internet connection (24.5%);

- inconvenience in using platforms for online lectures (18.2%);

- no difficulties (13.6%).

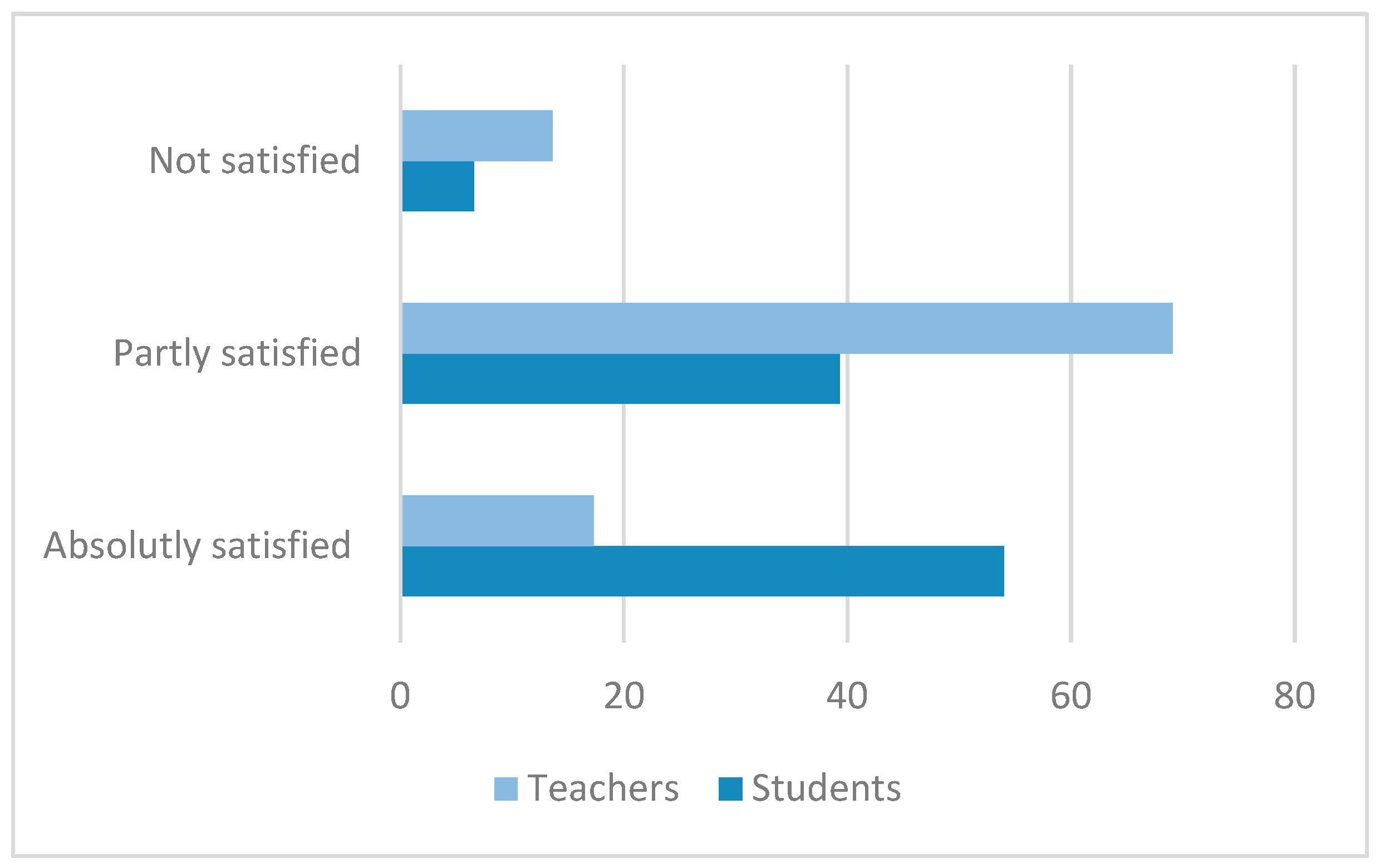

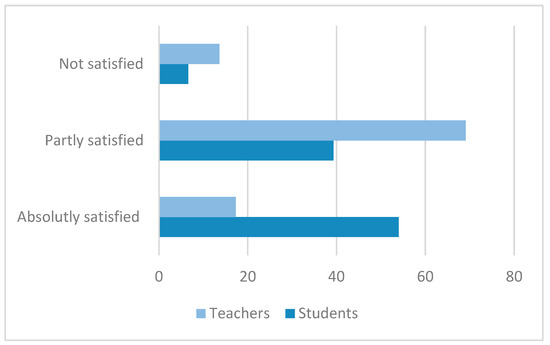

The level of satisfaction with the organization of online learning at the university according to students and teachers is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Result of satisfaction of the organization’s online-studies format (%).

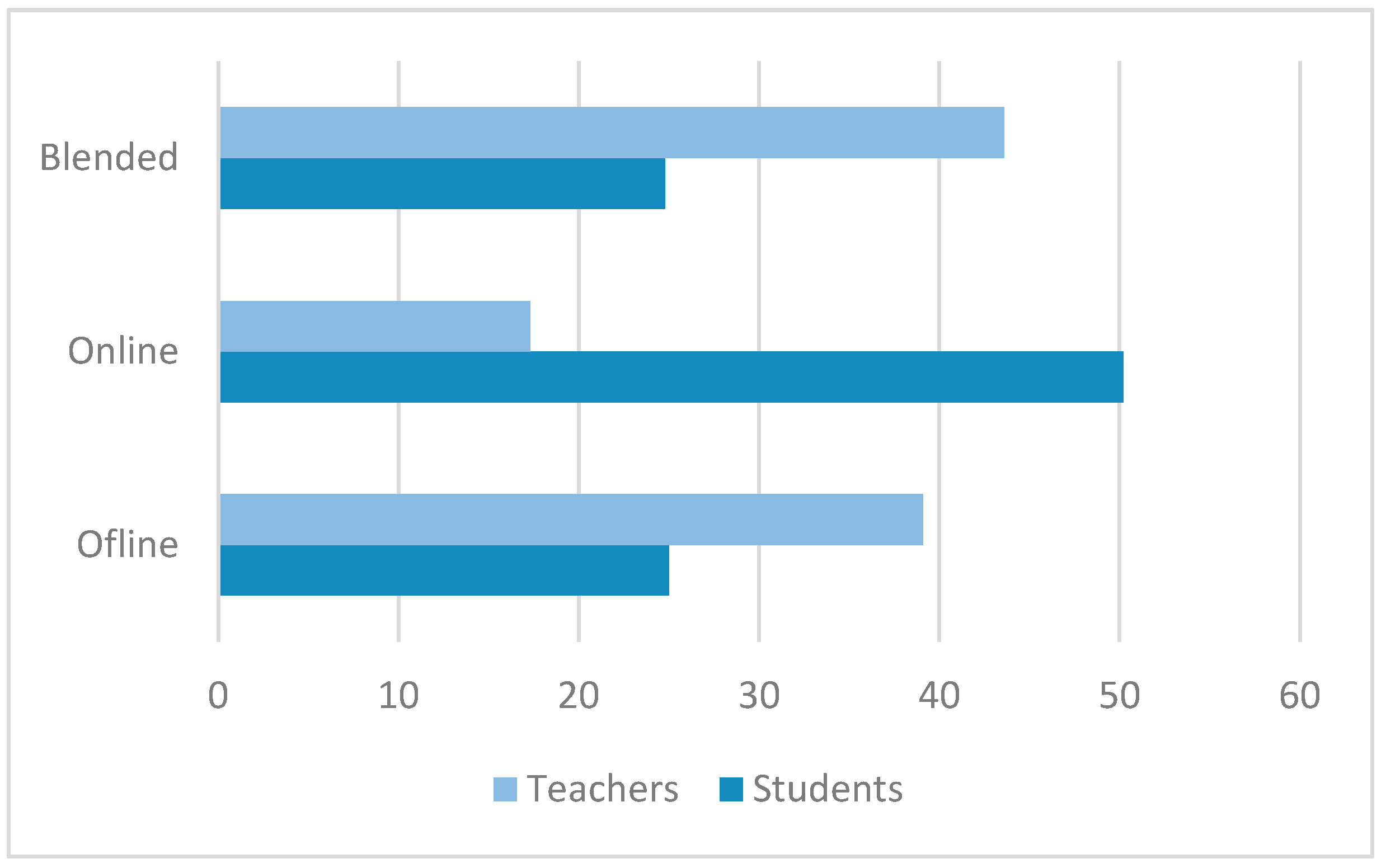

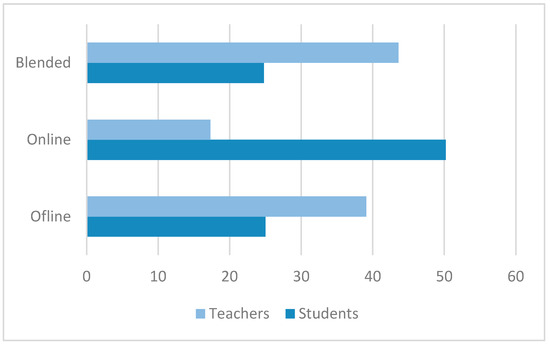

The distribution of respondents’ answers on the priority format of further education in the period of COVID-19 is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Results of the priority format for further studies in the period of COVID-19 (%).

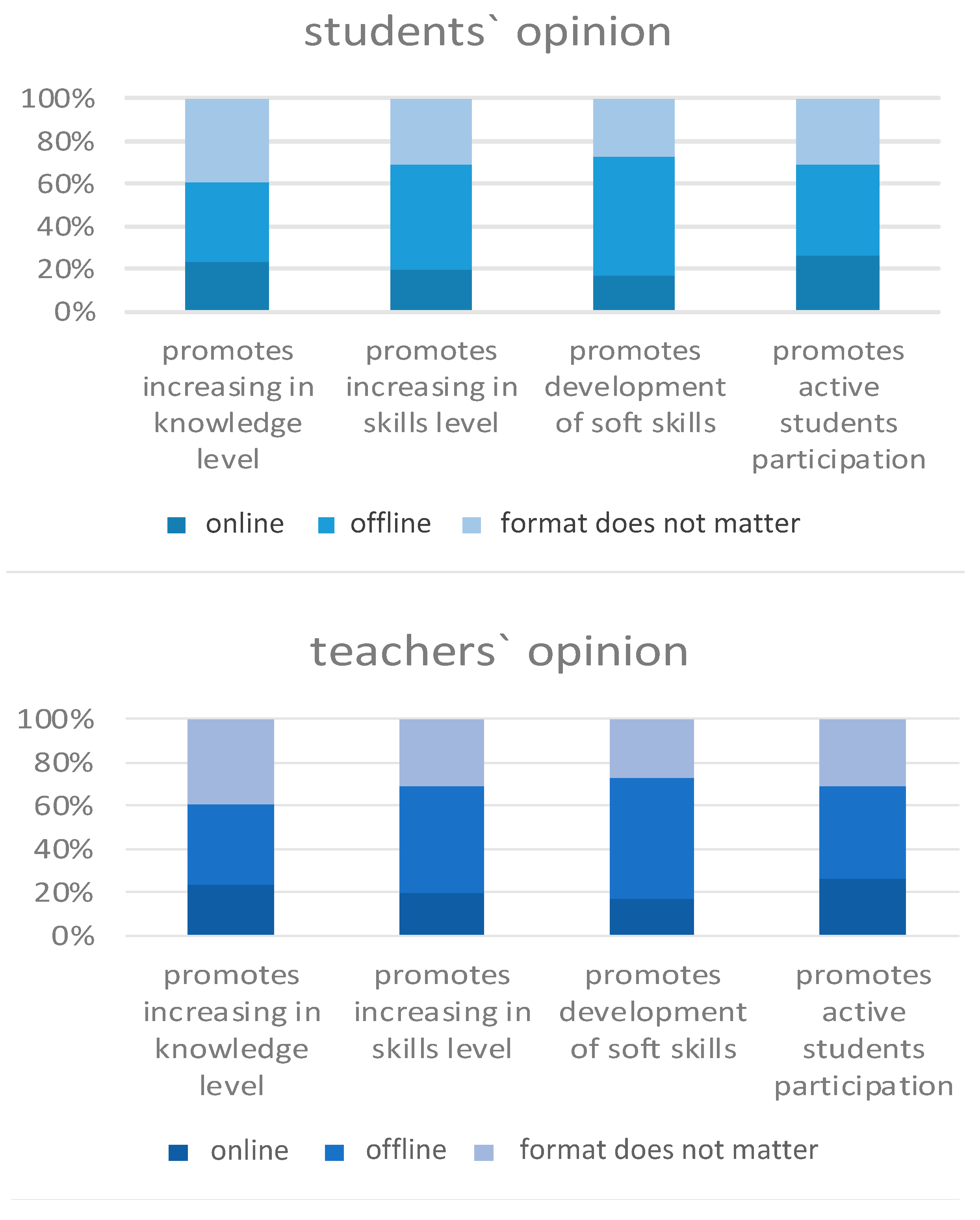

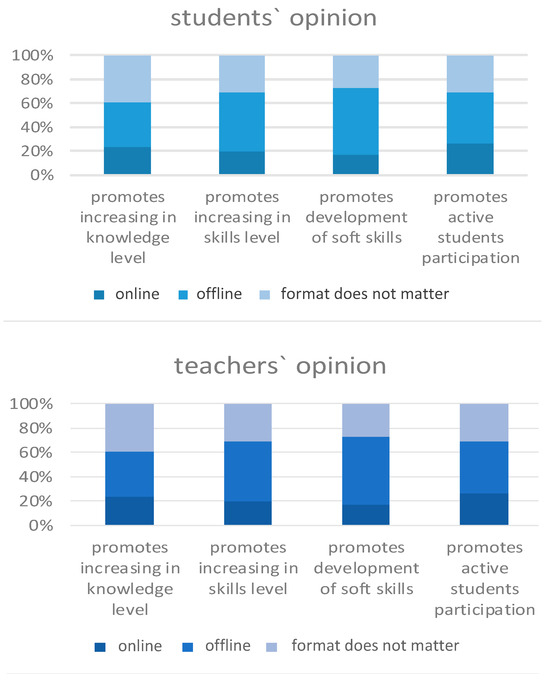

In addition, we asked students and teachers for their opinion on which format of classes is more favourable for improving the level of knowledge, skills, development of social skills, and student activity (reports, participation in discussions, questions, initiative, etc.). The results of the answers are presented in the Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Result of students’ and teachers’ opinion on the dependence of study formats on educational development (%).

Students identified the following benefits of online learning based on their opinion:

- the opportunity to stay at home (77.6%);

- increase in free time (76.9%), mobility, and efficiency (62.7%);

- the opportunity to acquire additional knowledge (37.7%);

- individual approach (30%);

- interactivity of classes (19.7%).

The benefits of online learning according to teachers are distributed as follows:

- mobility and efficiency (69.1%);

- the opportunity to stay at home (60.9%);

- the opportunity to acquire additional knowledge (40.9%);

- interactivity of classes (30.9%);

- more of free time (17.3%).

The answers of the surveyed students about the shortcomings of online learning were distributed as follows:

- technical issues (61.4%);

- lack of face-to-face communication (53.7%);

- lack of self-discipline (29.7%);

- heavy workload (22.8%);

- insufficient provision of educational content (21%).

Teachers responded to the shortcomings of online learning as follows:

- lack of face-to-face communication (85.5%);

- heavy workload (55.5%);

- technical issues (54.5%);

- lack of self-discipline (30.9%);

- insufficient provision of educational content (18.2%).

4. Results, Analysis, and Discussion

The results of the study show that the majority of Chernihiv Polytechnic National University students are positive about online learning: 34.9% did not face any challenges during the transition of education to online mode; almost all respondents (except 6.6% dissatisfied) are completely (54%) or partially (39.3%) satisfied with the organization of online education at the university. At the same time, among teachers, only 13.6% of respondents did not experience any challenges in online learning; those who are partially satisfied with the organization of online learning predominate (69.1%). In the future, half of the surveyed students (50.2%) prefer online learning, while teachers are mostly for mixed mode (43.6%) or return to offline learning (39.1%).

The study of aspects of positive and negative perceptions as well as the advantages and disadvantages of online learning by students and teachers provides an understanding of possible reasons that explain the level of satisfaction and willingness to continue the online format by participants in the educational process. Students are generally satisfied with online learning because of the opportunity to save time (84%) and gain easier access to educational materials (52.6%). For teachers, the transition to online mode was an impetus to master digital technology (61.8% of respondents) and an opportunity to be more mobile (59.1%). The advantages of online learning, according to both students and teachers, are the ability to stay at home, mobility, efficiency, and the ability to acquire additional knowledge. According to the students’ answers, time spent learning during the period of online study has increased, while teachers are required to spend more time on preparation for online classes and checking of assignments (40.9% of respondents noted an increase in time loss). Decreased socialization and face-to-face communication are signs of a negative online learning experience for both students and teachers. Teachers are also concerned about the difficulty of motivating students to study (50% of respondents), which was actually confirmed by the students themselves, noting the difficulty of self-motivation for online learning as a disadvantage (38.9%).

Similar results on the shortcomings of online learning are demonstrated by relevant foreign studies [6,46,47]. First, it is difficult for students to focus on learning due to distractions at home; it is difficult for them to motivate and control themselves. Second, students feel isolated because of the lack of interaction, especially with teachers; they are forced to spend more time in front of the computer due to a pandemic that has forced people to socially distance themselves from other people. The authors of [47] state that during the pandemic, the hierarchy of reasons why students are unmotivated to study online changed. Most often, the problems were technical, which reduced the motivation of students. The lack of technical skills of teachers was another important reason that, according to the authors, caused a loss of focus of students in learning and made it impossible to ensure a quality educational process.

Lack of access to professional equipment as a disadvantage of online learning was noted by a small number of teacher respondents (16.4%). Instead, 25.3% of surveyed students consider it a significant disadvantage of the online format. As noted above, this is not the first experience for respondents to switch to online learning. A previous study conducted at Chernihiv Polytechnic National University last year on the challenges and opportunities of conducting research during total quarantine restrictions showed that university faculty adapted to quarantine restrictions and were able to conduct research with access to professional equipment. Regarding students, based on demographic data, 42% of respondents were first-year students who did not have experience in practical work, so they worried about the possible lack of access to professional equipment [48].

Both teachers and students in our study pointed out the technical shortcomings of online learning, lack of face-to-face communication, and lack of self-discipline. Students mostly explain the challenges of online learning by the lack of continuous access to the Internet (36.4%), the inconvenience of using the university platform for distance education (28.4%), and the use of other platforms for online lectures (28.4%). On the other hand, for teachers the biggest challenges of online learning are related to the passiveness of students during classes (noted by 60.9% of respondents) and the lack of students connected (55.5%).

A study similar to ours was conducted by fellow Ukrainian scientists last year at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was reported that distance learning enabled the surveyed students to study at a convenient time, at a chosen pace (on time for courses), and in a place where that is convenient; some of them were actively engaged in self-education at that time [49]. Here, it is important to note that distance learning, although it gives the opportunity to learn at a convenient time, also eliminates synchronous interaction and direct communication during the lesson. In our study, we analyse online learning because this is the approach that Chernihiv Polytechnic National University operates under quarantine restrictions. Similar to our study, in the study [49], the main challenge of learning in the pandemic is the technical aspects associated with limited Internet access.

We agree with [47], where concluded that when learning exclusively through the Internet, some of the advantages of this format remain underestimated by participants, and the disadvantages become increasingly apparent. Similar to our research, student respondents of the foreign study answered that online learning alone is not favourable for the development of soft skills.

We agree with [50,51], where shown that attitudes towards the convenience and accessibility of platforms will play an important role in the future planning of educational strategy, and accordingly technology will become a necessary educational tool in traditional, virtual, or mixed classes in the world. Therefore, infrastructural and technical support of the academic community’s efforts is needed in the form of updated teaching and learning platforms as well as trainings for teachers on the development and improvement of virtual learning.

A portion of students and teachers noted the inconvenience of using platforms for online classes as a disadvantage of the online format (28.4% of surveyed students and 18.2% of surveyed teachers pointed this out). The importance of learning platforms when taking a course in a blended or e-learning environment is confirmed by research [52,53]. In [52] participants identified a learning platform as one of the components that needed to be improved. Similar to our study, participants identified the lack of face-to-face interaction as a challenge to online learning. We agree with the authors that teachers can organize virtual joint problem-solving activities and offer students team tasks, hackathons, etc. to facilitate student interaction and active learning to address the challenge above.

In our study, the majority of surveyed students (50.2%) preferred online learning during the next semester; the other half of the respondents were divided between offline learning (25%) and blended (24.8%). In similar studies to ours, respondents prefer a mixed format instead of completely offline or online [54] or, as in our results, prefer to continue learning online or combine contact and e-learning (mixed format) [55].

Our research and other studies suggest [46] that the demand for online or blended education in the future will be not only due to pandemics or natural disasters, but as an opportunity to meet the need for mobility and efficiency of knowledge acquisition, time saving, and inclusiveness. At the same time, we support the point about increasing students’ demand for online courses, provided that teachers will be able to interest them and organize high-quality interactive online teaching.

In the spring of 2023, an additional survey was conducted, which showed that 73.3% of students were in favor of online learning, 16.8% were in favor of classroom-based education, and 9.5% were in favor of mixed education [56].

However, it is important for higher education management to remember that not all students have access to online education and the necessary technical means to connect to the courses. University management should consider ways to help students who are left without access to lectures and teaching materials, as well as consider supportive methods of providing quality higher education. Thus, in response to military challenges, the university management of Chernihiv Polytechnic National University rethinks and forms a new vision for further development based on sustainability principles to recover educational and research infrastructures, promote human capital development, and modernize the learning environment [57].

In any case, universities need to interact with their students through surveys to get feedback that will allow them to improve the way they organize online education.

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused not only sanitary problems but also socio-economic difficulties on a global scale. Ensuring that students continue their education, despite the many limitations of social distancing, is one of them. In this context, online learning has become a very useful alternative. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of improving the quality of online learning for higher education.

Research has shown that online education, in addition to solving its primary task-providing education at a distance, can be a great addition to the full-time form, as technologies used in the development of e-learning courses can be important support for improving the quality and efficiency of traditional learning.

A peculiarity of this study is its goal to determine the perception of positive and negative aspects of online learning by students and teachers of Chernihiv Polytechnic National University, identify the strengths and weaknesses of the online format of higher education, determine the benefits and challenges of online learning from the perspective of students and teachers, and study their readiness to continue online learning in case of possible further quarantine restrictions. The author’s definition of the term “online learning” is proposed.

In addition, the authors give recommendations for measures that can help overcome the identified issues and suggest ways to solve them that will be useful for the management of higher education institutions and help provide managers with tools and mechanisms to respond effectively to challenges in higher education sphere in modern conditions.

The use of effective methods of distance learning through various digital platforms is recommended. Specifically, for conducting online sessions, the MS Teams platform could be used, where students are grouped for interaction and exchange of electronic content. Online lectures and self-study materials are accessible through MS Teams and the Moodle distance learning platform. Additionally, it is noteworthy that the electronic format for maintaining academic records is recommended, and students can use digital grade books. The process of selecting the elective courses is also recommended to be conducted electronically, ensuring convenience and accessibility for students.

At the same time, online learning is not an alternative to face-to-face training, but only an aid that is used until the situation with the coronavirus in the world stabilizes. Of course, graduates should visit universities; communicate with classmates; study; make friends; discuss; acquire new knowledge, skills, and abilities; express their own opinions; and work in a team. No online platform, service, or gadget can replace full-fledged live communication. However, taking into account the current challenges facing humanity, we must be prepared to defend them effectively in order to preserve the happy future of next generations. Therefore, e-learning in higher education systems and the use of modern information technologies are the key instruments to address today’s challenges.

Note that the acquired experience of online education during the pandemic allows the domestic education system to withstand and ensure the proper quality of higher education during adversities. “Lessons of the pandemic” help to withstand and overcome the modern challenges faced by the Ukrainian higher education system and continue to ensure the quality of education at the appropriate level.

Future research could be devoted to testing and analyzing the students’ and teachers’ experience for different cases (online, in person and blended). Since the educational process was switched to blended mode in autumn 2023, a substantiated comparison for the mentioned learning modes could be provided as soon as this semester finishes and participants have acquired their first experience of learning and teaching in such format.

Comparing to the COVID situation, students learning within a war state face numerous additional challenges that can significantly impact their educational experience. Some of the main difficulties include the following:

- Safety concerns. The primary and most immediate difficulty is the threat to personal safety. In a war state, students may be exposed to violence, conflict zones, and the general insecurity that can compromise their physical and mental well-being.

- Displacement and migration. Many students may experience forced displacement, fleeing their homes due to conflict. This can disrupt their education, leading to interruptions, changes in schedules, and difficulties in adjusting to new environments.

- Infrastructure and access to education. War often damages or disrupts infrastructure, including university research and educational facilities. Access to quality education becomes a challenge as education institutions may be destroyed, inaccessible, or repurposed for other uses.

- Psychological and emotional impact. Exposure to violence, displacement, and the overall insecurity of a war state can have profound psychological and emotional effects on students. Trauma, stress, and anxiety can hinder their ability to focus and engage in learning.

- Lack of resources. During a war, states often suffer from economic challenges, leading to a lack of resources for education. The educational institutions may lack basic supplies, qualified teachers, and necessary technology, hindering the quality of education.

- Disrupted curriculum. Continuous disruptions and uncertainties in a war state can lead to a fragmented curriculum. Students may struggle to follow a structured learning path, impacting their academic progress.

Addressing these difficulties requires a comprehensive approach, including humanitarian aid, rebuilding infrastructure, psychosocial support, and efforts to restore a sense of normalcy and stability to the lives of students in war-affected areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.L. and S.S.; methodology, A.V., I.L. and O.N.; software, A.V.; validation, O.N. and H.D.; formal analysis, I.L. and S.S.; investigation, I.L. and A.V.; resources, O.N. and A.V.; data curation, A.V., I.L., H.D. and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.D., I.L. and A.V.; writing—review and editing, H.D., O.N. and S.S.; visualization, I.L. and A.V.; supervision, O.N. and S.S.; project administration, S.S. and A.V.; funding acquisition, O.N. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data supporting reported results can be found in publicly available sources, which are linked in the references.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 100 Essential E-Learning Statistics for 2021. Available online: https://e-student.org/e-learning-statistics/#online-education-statistics (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Luik, P.; Lepp, M. Local and External Stakeholders Affecting Educational Change during the Coronavirus Pandemic: A Study of Facebook Messages in Estonia. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffin, E. E-Learning and Digital Education—Statistics & Facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/3115/e-learning-and-digital-education/ (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Online Education Market Size, Share Global Analysis Report, 2023–2030. Available online: https://www.fnfresearch.com/online-education-market (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Oraif, I.; Elyas, T. The Impact of COVID-19 on Learning: Investigating EFL Learners’ Engagement in Online Courses in Saudi Arabia. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poláková, P.; Klímová, B. The Perception of Slovak Students on Distance Online Learning in the Time of Coronavirus—A Preliminary Study. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.Y.; Rajkhan, A.A. E-Learning Critical Success Factors during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comprehensive Analysis of E-Learning Managerial Perspectives. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moawad, R.A. Online Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Academic Stress in University Students. Rev. Rom. Pentru Educ. Multidimens. 2020, 12 (Suppl. S2), 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, F.V.; Ambra, F.I.; Aruta, L.; Iavarone, M.L. Distance Learning in the COVID-19 Era: Perceptions in Southern Italy. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiberg, M.; Lyrén, P.-E.; Lind Pantzare, A. Schools, Universities and Large-Scale Assessment Responses to COVID-19: The Swedish Example. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peimani, N.; Kamalipour, H. Online Education and the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Case Study of Online Teaching during Lockdown. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelles, L.A.; Lord, S.M.; Hoople, G.D.; Chen, D.A.; Mejia, J.A. Compassionate Flexibility and Self-Discipline: Student Adaptation to Emergency Remote Teaching in an Integrated Engineering Energy Course during COVID-19. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, K.A.A.; Silva, E.K.d.; Gunawardhana, N. Online Delivery and Assessment during COVID-19: Safeguarding Academic Integrity. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, K.A.A.; Wijesuriya, D.I.; Ekanayake, S.Y.; Rennie, A.E.W.; Lambert, C.G.; Gunawardhana, N. Online Delivery of Teaching and Laboratory Practices: Continuity of University Programmes during COVID-19 Pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, J.; Al-Fuqaha, A. A Student Primer on How to Thrive in Engineering Education during and beyond COVID-19. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junus, K.; Santoso, H.B.; Putra, P.O.H.; Gandhi, A.; Siswantining, T. Lecturer Readiness for Online Classes during the Pandemic: A Survey Research. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, L.; Aaviku, T.; Leijen, Ä.; Pedaste, M.; Saks, K. Teaching during COVID-19: The Decisions Made in Teaching. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martha, A.S.D.; Junus, K.; Santoso, H.B.; Suhartanto, H. Assessing Undergraduate Students’ e-Learning Competencies: A Case Study of Higher Education Context in Indonesia. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuck, R.K.; Lambert, R. “Am I Doing Enough?” Special Educators’ Experiences with Emergency Remote Teaching in Spring 2020. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.u.N.; Algahtani, F.D.; Zrieq, R.; Aldhmadi, B.K.; Atta, A.; Obeidat, R.M.; Kadri, A. Academic Self-Perception and Course Satisfaction among University Students Taking Virtual Classes during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Kingdom of Saudi-Arabia (KSA). Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Alberti, M.; Suárez, F.; Chiyón, I.; Mosquera Feijoo, J.C. Challenges and Experiences of Online Evaluation in Courses of Civil Engineering during the Lockdown Learning Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassoued, Z.; Alhendawi, M.; Bashitialshaaer, R. An Exploratory Study of the Obstacles for Achieving Quality in Distance Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, P.; Bento, F.; Tagliabue, M. A Scoping Review of Organizational Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Schools: A Complex Systems Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Khalil, V.; Helou, S.; Khalifé, E.; Chen, M.A.; Majumdar, R.; Ogata, H. Emergency Online Learning in Low-Resource Settings: Effective Student Engagement Strategies. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.M.; Goh, C.; Lim, L.Z.; Gao, X. COVID-19 Emergency eLearning and Beyond: Experiences and Perspectives of University Educators. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahleez, K.A.; El-Saleh, A.A.; Al Alawi, A.M.; Abdel Fattah, F.A.M. Student learning outcomes and online engagement in time of crisis: The role of e-learning system usability and teacher behavior. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2021, 38, 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, F.; Al Alawi, A.M.; Dahleez, K.A.; El Saleh, A. Reviewing the critical challenges that influence the adoption of the e-learning system in higher educational institutions in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Online Inf. Rev. 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Centre for Technical and Vocational Education and Training. Available online: https://unevoc.unesco.org/home/TVETipedia+Glossary/lang=en/filt=all/id=188 (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Rosenberg, M. E-Learning: Strategies for Delivering Knowledge in the Digital Age, 1st ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Berkshire, UK, 2000; p. 344. [Google Scholar]

- Rossett, A.; Sheldon, K. Beyond the Podium: Delivering Training and Performance to a Digital World; Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- Adrich, C. Simulations and the Future of Learning: An Innovative (and Perhaps Revolutionary) Approach to e-Learning; Pfeiffer: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, T. National strategies for e-learning in post-secondary education and training. In Fundamentals of Educational Planning; Unesco Iiep: Paris, France, 2001; Volume 70, p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Moeng, B. IBM Tackles Learning in the Workplace. IBM Management Development Solutions. 8 November 2004. Available online: http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/elearning/define.html (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Sawhey, N. E-learning: Global Education without Walls. Educ. Quest. Int. J. Educ. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Distance Learning Solutions. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/solutions (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Education: From Disruption to Recovery. Available online: https://webarchive.unesco.org/web/20220629024039/https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/ (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Richter, F. At Least 463 Million Students Cut off from Remote Learning. Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/22799/number-of-children-with-and-without-access-to-remote-learning-programs/ (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Higher Education: In-Person or Online? 29-Country Ipsos Survey for The World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2020-11/higher-education-in-person-or-online.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Buchholz, K. Will Higher Education Move Online? Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/23695/higher-education-online/ (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- COVID-19 in Latin America: Main Distance Learning Tools 2020|Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1184493/strategies-distance-learning-coronavirus-latin-america-type/#statisticContainer (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Organization of the Educational Process Using Distance Learning Technologies: Methodical Recommendations. Mykolaiv OIPPO. Available online: https://base.kristti.com.ua/?p=8366 (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Lysenko, I.; Stepenko, S.; Dyvnych, H. Indicators of Regional Innovation Clusters’ Effectiveness in the Higher Education System. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The COVID-19 Pandemic Has Changed Education Forever. This Is How. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-education-global-covid19-online-digital-learning/ (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Smirnova, O. “False Education”. How the Pandemic Exposed the Problems of Online Learning. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/ukrainian/features-54039740 (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Mills, M.; Te Riele, K.; McGregor, G.; Baroutsis, A. Teaching in Alternative and Flexible Education Settings. Teach. Educ. 2017, 28, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Van Wart, M.; Ni, A.; Medina, P.; Canelon, J.; Kordrostami, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. Integrating students’ perspectives about online learning: A hierarchy of factors. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2020, 17, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coman, C.; Țîru, L.G.; Meseșan-Schmitz, L.; Stanciu, C.; Bularca, M.C. Online Teaching and Learning in Higher Education during the Coronavirus Pandemic: Students’ Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbytska, A.; Syzonenko, O. Forced Virtualization for Research Activities at the Universities: Challenges and Solutions. Rev. Rom. Pentru Educ. Multidimens. 2020, 12 (Suppl. S1), 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenko, Y.; Kybalna, N.; Snisarenko, Y. The COVID-19 Distance Learning: Insight from Ukrainian students. Rev. Bras. Educ. Camp. 2020, 5, e8925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaili, Y. Evaluation of students’ attitude toward distance learning during the pandemic (COVID-19): A case study of ELTE university. Horizion 2021, 29, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkawi, E.; Bawaneh, A.K.; Bawa’aneh, M.S. Campus off, Education on: UAEU Students’ Satisfaction and Attitudes towards E-Learning and Virtual Classes during COVID-19 Pandemic. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2021, 13, ep283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giray, G. An assessment of student satisfaction with e-learning: An empirical study with computer and software engineering undergraduate students in Turkey under pandemic conditions. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 6651–6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdogmus, H.; Péraire, C. Flipping a graduate-level software engineering foundations course. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/ACM 39th International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering Education and Training Track (ICSE-SEET), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 20–28 May 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Almusharraf, N.; Khahro, S. Students Satisfaction with Online Learning Experiences during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. (Ijet) 2020, 15, 246–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puljak, L.; Čivljak, M.; Haramina, A.; Mališa, S.; Čavić, D.; Klinec, D.; Aranza, D.; Mesarić, J.; Skitarelić, N.; Zoranić, S.; et al. Attitudes and concerns of undergraduate university health sciences students in Croatia regarding complete switch to e-learning during COVID-19 pandemic: A survey. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Survey Regarding the Form of Educational Process in the Spring Semester 2022/2023 Academic Year. Available online: https://stu.cn.ua/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/opytuvannya-shhodo-formy-navchalnogo-proczesu-u-2-semestri-2022_23-navchalnogo-roku.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Novomlynets, O.; Marhasova, V.; Tkalenko, N.; Kholiavko, N.; Popelo, O. Northern outpost: Chernihiv Polytechnic National University in the conditions of the russia-Ukrainian war. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2023, 21, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).