Study on the Collaboration between University and Educational Centers Mentors in the Development of the In-School Education Placements in Official University Degrees Qualifying for the Teaching Profession: The Case of the University of Santiago de Compostela

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure and Data Analysis

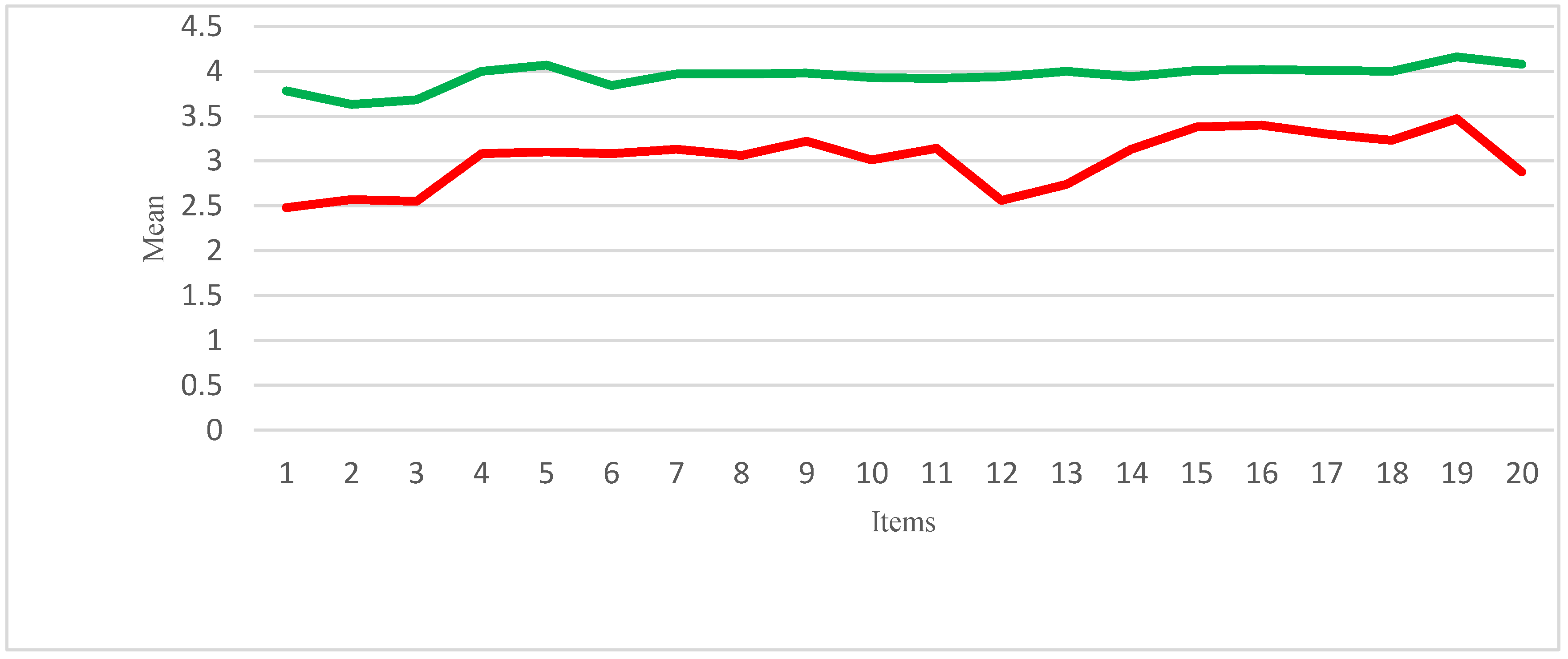

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zabalza, M.A. Practicum y formación. In ¿En qué puede formar el Practicum? En M.Raposo Rivas, M.E., Martínez Filgueira, L., Lodeiro Enjo, J.C., Eds.; Fernández de la Iglesia, y A. Pérez Abellás (Coords.), El Practicum más allá del empleo. Formación vs. Training; Imprenta Universitaria: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2009; pp. 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zabalza, M.A. El prácticum como contexto de aprendizaje. In Un Practicum Para la Formación Integral de los Estudiantes; en Muñoz Carril, P.C., Raposo-Rivas, M., González Sanmamed, M., Martínez-Figueira, M.E., Zabalza-Cerdeiriña, M., Pérez-Abellás, A., Eds.; Andavira: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. The Teaching Profession in Europe: Practices, Perceptions, and Policies; Eurydice Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jyrhäma, R. La función de los estudios prácticos en la formación del profesorado. In Aprender de Finlandia. La Apuesta por un Profesorado Investigador; de Jakku-Sihvonen Ritva y, N.H., Ed.; Ministerio de Educación. Editorial Kaleida Forma: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Blández-Angel, J. La evaluación de la titulación de maestro especialista en Educación Física de la Facultad de Educación de la UCM a través del plan nacional. In Formación Inicial y Permanente del Profesor de Educación Física; En Onofre Contreras, J., Ed.; Universidad de Castilla la Mancha: Ciudad Real, Spain, 2000; pp. 539–548. [Google Scholar]

- Tejada, J. El prácticum por competencias: Implicaciones metodológico-organizativas y evaluativas. Rev. Bordón 2006, 58, 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- González, M.; Fuentes, E. El Practicum en el aprendizaje de la profesión docente. Rev. De Educ. 2011, 354, 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hazel, F. Facets of Mentoring in Higher Education; Staff and Educational Development Association: Edgbaston, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Figueira, M.E.; Raposo Rivas, M. Funciones generales de la mentoría en el Practicum: Entre la realidad y el deseo en el desempeño de la acción mentorial. Rev. De Educ. 2011, 354, 155–181. [Google Scholar]

- Monereo, C.; Badia, A.; Martínez, J.R. Prediction of success in teamwork of secundary students. Rev. Psicodidáctica. 2013, 18, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valverde, A.; Ruiz, C.; García, E.; Romero Rodríguez, S. Innovación en la orientación universitaria: La mentoría como respuesta. Rev. Contextos Educ. 2003, 6–7, 87–112. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, M.P.; Benarroch, A.; Jiménez, M.A.; Smith, G.; Rojas, G. ¿Se puede estimular la reflexión en el supervisor y en el alumno universitario durante el periodo de Practicum? Enseñanza 2006, 24, 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zeichner, K. Rethinking the Connections Between Campus Courses and Field Experiences in College- and University-Based. Teach. Educ. J. Teach. Educ. 2010, 61, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Z.; Yu, M.; Riezebos, P.A. Research framework of smart education. Smart Learn. Environ. 2016, 3, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Imbernón, F. Diseño, Desarrollo y Evaluación de los Procesos de Formación; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, E.; Bolivar, A.; Burgos-García, A.; Domingo, J.; Fernández, M.; Gallego-Arrufat, M.J.; Iranzo, P.; Guerrero, L.; López, M.C.; Carmen Merlos, M.; et al. La mejora del Practicum, esfuerzo de colaboración. Rev. Profr. Rev. De Currículum Y Form. De Profr. 2004, 8, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Molina Ruiz, E. Coordinación de las actuaciones de Practicum: Niveles y compromisos. In Actas del IX Symposium Internacional sobre Practicum y Prácticas en Empresas en la Formación Universitaria. Buenas Prácticas en el Practicum; Imprenta Universitaria: Pontevedra, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bullough, R., Jr. Being and becoming a mentor: School-based teacher educators and teacher educator identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2005, 21, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megía Cuélliga, C. Competencias del Profesor Mentor del Aprendiz de Maestro. Una Propuesta de Formación. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Educación a Distancia, Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, M.; Esteve, O.; Badiá, M.; Farró, L.; Lope, S. Empoderamiento a mentores de universidad y mentores de centro mediante una formación a medida basada en la práctica reflexiva. In Actas del XV Symposium Internacional Sobre Practicum y Prácticas en Empresas en la Formación Universitaria. Presente y Retos de Futuro; Imprenta Universitaria: Pontevedra, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, M.; Franco, M. Programa de mentoría Blanquerna-Escuela. In Actas del XVI Symposium Internacional Sobre Practicum y Prácticas en Empresas en la Formación Universitaria. Prácticas Externas Virtuales versus Presenciales; Imprenta Universitaria: Pontevedra, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Bernardo, P.; Sánchez-Tarazaga, L.; Sanahuja Ribés, A. Motivaciones, expectativas y beneficios del prácticum desde la visión de los tutores de los centros educativos. Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. De Form. Del Profr. 2022, 25, 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Porto, M.; y Bolarín, M.J. Revisando las prácticas escolares: Valoraciones de maestros mentores. Revista de curriculum y formación del profesorado, 17.2. 2013. Available online: http://www.ugr.es/local/recfpro/rev172COL13.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- López Jiménez, T.M. Ayuda Educativa y Reflexión Conjunta Sobre la Propia Práctica en el Prácticum de Educación Infantil. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Arrufat, M.J.; Cebrián-de-la-Serna, M.; Contribuciones de las tecnologías para la evaluación formativa en el prácticum. Profesorado. Rev. De Currículum Y Form. De Profr. 2018, 22, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabalza, M.A. El prácticum en la formación universitaria: Estado de la cuestión. Rev. De Educ. 2011, 354, 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- González, M.O.; Huerta, P.; Gómez, H.; Flores, J.M. Retos y perspectivas de las prácticas profesionales mediadas por TIC. In Actas del XVI Symposium Internacional Sobre Practicum y Prácticas en Empresas en la Formación Universitaria. Prácticas Externas Virtuales versus Presenciales; Imprenta Universitaria: Pontevedra, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, N.; Gallego, M.J. La protección de datos: Una necesidad para prácticas externas seguras. In Actas del XVI Symposium Internacional Sobre Practicum y Prácticas en Empresas en la Formación Universitaria. Prácticas Externas Virtuales versus Presenciales; Imprenta Universitaria: Pontevedra, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Items | Activities/Procedures | Cronbach’s Alpha If the Item Has Been Deleted | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Question | Question Need | ||

| 1 | Contacts, meetings, curricular coordination between the Faculty of Education and the educational center. | 0.972 | 0.973 |

| 2 | Selection of schools (profile, criteria...). | 0.972 | 0.973 |

| 3 | Selection of mentors from the university and the educational centers (profile, criteria...). | 0.971 | 0.972 |

| 4 | Establishment of norms, rules, procedures, forms/channels of communication for the development of the internship. | 0.971 | 0.971 |

| 5 | Elaboration of guidelines for the organization of the internship. | 0.971 | 0.972 |

| 6 | Elaboration of guidelines for the organization of the internship Final Report. | 0.972 | 0.972 |

| 7 | Orientation of the future teacher for recording and reporting on the internship experience. | 0.971 | 0.972 |

| 8 | Preparatory training of the future teacher for the internship. | 0.971 | 0.972 |

| 9 | Contextualization of the internship in the local community, the educational center, and the classroom/student group. | 0.971 | 0.972 |

| 10 | Development of instruments, tools, and criteria for student evaluation by future teachers. | 0.971 | 0.972 |

| 11 | Preparation, writing and presentation of educational materials, learning resources, monitoring instruments and reports. | 0.971 | 0.971 |

| 12 | Collaborative work between the university mentor and the school mentor. | 0.971 | 0.972 |

| 13 | Common process of supervision of teaching practices. | 0.971 | 0.972 |

| 14 | Direct classroom/practice observation. | 0.972 | 0.972 |

| 15 | Written or oral feedback to the future teacher. | 0.971 | 0.971 |

| 16 | Supervision of activities, tasks, and planning of teaching activities by the prospective teacher. | 0.972 | 0.971 |

| 17 | Supervision of the prospective teacher in his/her preparation of teaching support materials/resources. | 0.971 | 0.971 |

| 18 | Monitoring and analysis of the progress of future teachers. | 0.971 | 0.971 |

| 19 | Motivate future teachers for educational innovation. | 0.972 | 0.972 |

| 20 | Collaborative work between internship mentors (university and center) and future teachers. | 0.972 | 0.972 |

| Items | Activities/Procedures | Collaboration | N | Mean | Median | SD | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Contacts, meetings, curricular coordination between the Faculty of Education and the educational center. | Current | 202 | 2.48 | 2.00 | 1.21 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 3.78 | 4.00 | 1.18 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 2 | Selection of schools (profile, criteria...). | Current | 202 | 2.57 | 3.00 | 1.31 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 3.63 | 4.00 | 1.18 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 3 | Selection of mentors from the university and the educational centers (profile, criteria...). | Current | 202 | 2.55 | 3.00 | 1.31 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 3.68 | 4.00 | 1.16 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 4 | Establishment of norms, rules, procedures, forms/channels of communication for the development of the internship. | Current | 202 | 3.08 | 3.00 | 1.23 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 5 | Elaboration of guidelines for the organization of the internship. | Current | 202 | 3.10 | 3.00 | 1.32 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 4.07 | 4.00 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 6 | Elaboration of guidelines for the organization of the internship Final Report. | Current | 202 | 3.08 | 3.00 | 1.30 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 3.84 | 4.00 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 7 | Orientation of the future teacher for recording and reporting on the internship experience. | Current | 202 | 3.13 | 3.00 | 1.22 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 3.97 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 8 | Preparatory training of the future teacher for the internship. | Current | 202 | 3.06 | 3.00 | 1.28 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 3.97 | 4.00 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 9 | Contextualization of the internship in the local community, the educational center, and the classroom/student group. | Current | 202 | 3.22 | 3.00 | 1.29 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 3.98 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 10 | Development of instruments, tools, and criteria for student evaluation by future teachers. | Current | 202 | 3.01 | 3.00 | 1.24 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 3.93 | 4.00 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 11 | Preparation, writing and presentation of educational materials, learning resources, monitoring instruments and reports. | Current | 202 | 3.14 | 3.00 | 1.26 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 3.92 | 4.00 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 12 | Collaborative work between the university mentor and the school mentor. | Current | 202 | 2.56 | 2.00 | 1.32 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 3.94 | 4.00 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 13 | Common process of supervision of teaching practices. | Current | 202 | 2.74 | 3.00 | 1.32 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 14 | Direct classroom/practice observation. | Current | 202 | 3.13 | 3.00 | 1.47 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 3.94 | 4.00 | 1.13 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 15 | Written or oral feedback to the future teacher. | Current | 202 | 3.38 | 3.50 | 1.28 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 4.01 | 4.00 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 16 | Supervision of activities, tasks, and planning of teaching activities by the prospective teacher. | Current | 202 | 3.40 | 4.00 | 1.29 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 4.02 | 4.00 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 17 | Supervision of the prospective teacher in his/her preparation of teaching support materials/resources. | Current | 202 | 3.30 | 3.00 | 1.26 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 4.01 | 4.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 18 | Monitoring and analysis of the progress of future teachers. | Current | 202 | 3.23 | 3.00 | 1.29 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 19 | Motivate future teachers for educational innovation. | Current | 202 | 3.47 | 4.00 | 1.31 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 4.16 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| 20 | Collaborative work between internship mentors (university and center) and future teachers. | Current | 202 | 2.88 | 3.00 | 1.39 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Required | 202 | 4.08 | 4.00 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Items | Variables | Statistics | gl | p | Difference in Averages | EE of the Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Current | Required | −12.49 | 201 | <0.001 | −1.297 | 0.1039 |

| 2 | Current | Required | −10.10 | 201 | <0.001 | −1.054 | 0.1044 |

| 3 | Current | Required | −11.10 | 201 | <0.001 | −1.134 | 0.1021 |

| 4 | Current | Required | −9.92 | 201 | <0.001 | −0.926 | 0.0934 |

| 5 | Current | Required | −9.68 | 201 | <0.001 | −0.970 | 0.1002 |

| 6 | Current | Required | −7.84 | 201 | <0.001 | −0.757 | 0.0966 |

| 7 | Current | Required | −8.91 | 201 | <0.001 | −0.837 | 0.0938 |

| 8 | Current | Required | −9.09 | 201 | <0.001 | −0.906 | 0.0997 |

| 9 | Current | Required | −7.68 | 201 | <0.001 | −0.762 | 0.0993 |

| 10 | Current | Required | −9.28 | 201 | <0.001 | −0.916 | 0.0987 |

| 11 | Current | Required | −8.04 | 201 | <0.001 | −0.777 | 0.0966 |

| 12 | Current | Required | −12.54 | 201 | <0.001 | −1.376 | 0.1098 |

| 13 | Current | Required | −11.70 | 201 | <0.001 | −1.257 | 0.1074 |

| 14 | Current | Required | −7.54 | 201 | <0.001 | −0.812 | 0.1077 |

| 15 | Current | Required | −6.33 | 201 | <0.001 | −0.634 | 0.1001 |

| 16 | Current | Required | −6.22 | 201 | <0.001 | −0.619 | 0.0995 |

| 17 | Current | Required | −7.34 | 201 | <0.001 | −0.713 | 0.0972 |

| 18 | Current | Required | −7.60 | 201 | <0.001 | −0.772 | 0.1016 |

| 19 | Current | Required | −6.99 | 201 | <0.001 | −0.693 | 0.0991 |

| 20 | Current | Required | −10.69 | 201 | <0.001 | −1.198 | 0.1121 |

| Item | Colab. | Mentor | N | % of Frequencies and Average | Chi-Square | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Value | gl | Sig. | |||||

| 1 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 17.8 | 31.1 | 31.1 | 6.7 | 13.3 | 2.67 | |||

| Center | 157 | 27.4 | 29.3 | 21.7 | 16.6 | 5.1 | 2.43 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 2.2 | 28.9 | 60.0 | 4.36 | 22.478 | 4 | 0.000 | |

| Center | 157 | 7.0 | 8.9 | 26.8 | 30.6 | 26.8 | 3.61 | |||||

| 2 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 37.8 | 17.8 | 22.2 | 17.8 | 4.4 | 2.33 | |||

| Center | 157 | 26.8 | 19.7 | 26.1 | 17.2 | 10.2 | 2.64 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 8.9 | 6.7 | 20.0 | 28.9 | 35.6 | 3.76 | ||||

| Center | 157 | 5.1 | 12.7 | 27.4 | 27.4 | 27.4 | 3.59 | |||||

| 3 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 35.6 | 24.4 | 22.2 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 2.31 | |||

| Center | 157 | 27.4 | 19.1 | 28.0 | 15.3 | 10.2 | 2.62 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 2.2 | 6.7 | 24.4 | 15.6 | 51.1 | 4.07 | 12.085 | 4 | 0.017 | |

| Center | 157 | 5.1 | 13.4 | 26.1 | 29.9 | 25.5 | 3.57 | |||||

| 4 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 8.9 | 17.8 | 33.3 | 26.7 | 13.3 | 3.18 | |||

| Center | 157 | 14.0 | 19.1 | 29.3 | 22.9 | 14.6 | 3.05 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 8.9 | 35.6 | 51.1 | 4.31 | ||||

| Center | 157 | 4.5 | 3.2 | 23.6 | 33.8 | 35.0 | 3.92 | |||||

| 5 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 13.3 | 15.6 | 28.9 | 26.7 | 15.6 | 3.16 | |||

| Center | 157 | 14.0 | 24.2 | 19.7 | 23.6 | 18.5 | 3.08 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 17.8 | 28.9 | 51.1 | 4.27 | ||||

| Center | 157 | 3.8 | 5.1 | 17.8 | 32.5 | 40.8 | 4.01 | |||||

| 6 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 20.0 | 11.1 | 22.2 | 26.7 | 20.0 | 3.16 | |||

| Center | 157 | 14.0 | 20.4 | 24.8 | 26.8 | 14.0 | 3.06 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 28.9 | 26.7 | 35.6 | 3.84 | ||||

| Center | 157 | 3.8 | 5.7 | 25.5 | 32.5 | 32.5 | 3.84 | |||||

| 7 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 13.3 | 8.9 | 28.9 | 35.6 | 13.3 | 3.27 | |||

| Center | 157 | 14.0 | 15.9 | 29.3 | 28.0 | 12.7 | 3.10 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 2.2 | 11.1 | 15.6 | 26.7 | 44.4 | 4.00 | ||||

| Center | 157 | 2.5 | 3.8 | 21.7 | 38.9 | 33.1 | 3.96 | |||||

| 8 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 15.6 | 11.1 | 31.1 | 28.9 | 13.3 | 3.13 | |||

| Center | 157 | 15.9 | 17.8 | 26.8 | 24.8 | 14.6 | 3.04 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 2.2 | 4.4 | 15.6 | 31.1 | 46.7 | 4.16 | ||||

| Center | 157 | 3.2 | 5.7 | 20.4 | 37.6 | 33.1 | 3.92 | |||||

| 9 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 13.3 | 15.6 | 35.6 | 17.8 | 17.8 | 3.11 | |||

| Center | 157 | 13.4 | 14.6 | 24.8 | 28.0 | 19.1 | 3.25 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 2.2 | 4.4 | 6.7 | 42.2 | 44.4 | 4.22 | ||||

| Center | 157 | 3.8 | 5.1 | 17.8 | 42.7 | 30.6 | 3.91 | |||||

| 10 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 17.8 | 20.0 | 33.3 | 20.0 | 8.9 | 2.82 | |||

| Center | 157 | 15.3 | 16.6 | 26.1 | 29.9 | 12.1 | 3.07 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 2.2 | 11.1 | 17.8 | 22.2 | 46.7 | 4.00 | ||||

| Center | 157 | 3.8 | 5.7 | 19.7 | 36.9 | 33.8 | 3.91 | |||||

| 12 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 24.4 | 31.1 | 20.0 | 13.3 | 11.1 | 2.56 | |||

| Center | 157 | 28.7 | 22.9 | 22.3 | 15.9 | 10.2 | 2.56 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 6.7 | 2.2 | 11.1 | 13.3 | 66.7 | 4.31 | 22.192 | 4 | 0.000 | |

| Center | 157 | 4.5 | 5.7 | 22.3 | 37.6 | 29.9 | 3.83 | |||||

| 13 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 26.7 | 26.7 | 13.3 | 20.0 | 13.3 | 2.67 | |||

| Center | 157 | 20.4 | 25.5 | 23.6 | 19.1 | 11.5 | 2.76 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 6.7 | 4.4 | 6.7 | 20.0 | 62.2 | 4.27 | 17.306 | 4 | 0.002 | |

| Center | 157 | 3.2 | 4.5 | 21.7 | 38.9 | 31.8 | 3.92 | |||||

| 14 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 40.0 | 28.9 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 13.3 | 2.27 | 30.445 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Center | 157 | 15.9 | 8.9 | 25.5 | 21.0 | 28.7 | 3.38 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 22.2 | 8.9 | 51.1 | 3.84 | 13.295 | 4 | 0.010 | |

| Center | 157 | 3.8 | 5.7 | 17.2 | 36.3 | 36.9 | 3.97 | |||||

| 15 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 11.1 | 22.2 | 26.7 | 24.4 | 15.6 | 3.11 | |||

| Center | 157 | 11.5 | 10.2 | 25.5 | 27.4 | 25.5 | 3.45 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 20.0 | 22.2 | 53.3 | 4.22 | ||||

| Center | 157 | 3.2 | 5.7 | 21.0 | 33.1 | 36.9 | 3.95 | |||||

| 16 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 13.3 | 26.7 | 20.0 | 17.8 | 22.2 | 3.09 | 16.148 | 4 | 0.003 |

| Center | 157 | 11.5 | 6.4 | 28.0 | 29.9 | 24.2 | 3.49 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 2.2 | 4.4 | 11.1 | 40.0 | 42.2 | 4.16 | ||||

| Center | 157 | 3.2 | 5.1 | 15.3 | 43.3 | 33.1 | 3.98 | |||||

| 17 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 8.9 | 24.4 | 24.4 | 20.0 | 22.2 | 3.22 | |||

| Center | 157 | 12.1 | 12.1 | 26.8 | 29.9 | 19.1 | 3.32 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 2.2 | 4.4 | 6.7 | 35.6 | 51.1 | 4.29 | ||||

| Center | 157 | 2.5 | 7.0 | 17.2 | 41.4 | 31.8 | 3.93 | |||||

| 18 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 15.6 | 17.8 | 22.2 | 17.8 | 26.7 | 3.22 | |||

| Center | 157 | 12.7 | 14.0 | 27.4 | 28.7 | 17.2 | 3.24 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 2.2 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 22.2 | 57.8 | 4.24 | 14.086 | 4 | 0.007 | |

| Center | 157 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 21.0 | 40.1 | 31.8 | 3.94 | |||||

| 19 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 11.1 | 15.6 | 20.0 | 24.4 | 28.9 | 3.44 | |||

| Center | 157 | 10.8 | 12.1 | 22.3 | 28.0 | 26.8 | 3.48 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 0.0 | 8.9 | 6.7 | 20.0 | 64.4 | 4.40 | 9.809 | 4 | 0.044 | |

| Center | 157 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 17.8 | 31.2 | 43.9 | 4.10 | |||||

| 20 | Current | Univ. | 45 | 22.2 | 28.9 | 17.8 | 11.1 | 20.0 | 2.78 | |||

| Center | 157 | 22.3 | 17.2 | 22.3 | 23.6 | 14.6 | 2.91 | |||||

| Required | Univ. | 45 | 2.2 | 6.7 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 68.9 | 4.38 | 15.354 | 4 | 0.004 | |

| Center | ||||||||||||

| Item | Colab. | Mentor | N | % of Frequencies and Average | Chi-Square | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Valor | gl | Sig. | |||||

| 1 | Current | E.I. | 65 | 29.2 | 36.9 | 21.5 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 2.23 | 9.836 | 4 | 0.042 |

| E.M. | 92 | 26.1 | 23.9 | 21.7 | 23.9 | 4.3 | 2.57 | |||||

| Required | E.I. | 65 | 9.2 | 12.3 | 30.8 | 18.5 | 29.2 | 3.46 | ||||

| E.M. | 92 | 5.4 | 6.5 | 23.9 | 39.1 | 25.0 | 3.72 | |||||

| 5 | Current | E.I. | 65 | 18.5 | 29.2 | 23.1 | 13.8 | 15.4 | 2.78 | |||

| E.M. | 92 | 10.9 | 20.7 | 17.4 | 30.4 | 20.7 | 3.29 | |||||

| Required | E.I. | 65 | 4.6 | 10.8 | 20.0 | 23.1 | 41.5 | 3.86 | 10.520 | 4 | 0.033 | |

| E.M. | 92 | 3.3 | 1.1 | 16.3 | 39.1 | 40.2 | 4.12 | |||||

| 8 | Current | E.I. | 65 | 16.9 | 23.1 | 24.6 | 18.5 | 16.9 | 2.95 | |||

| E.M. | 92 | 15.2 | 14.1 | 28.3 | 29.3 | 13.0 | 3.11 | |||||

| Required | E.I. | 65 | 4.6 | 12.3 | 20.0 | 32.2 | 30.8 | 3.72 | 10.092 | 4 | 0.039 | |

| E.M. | 92 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 20.7 | 41.3 | 34.8 | 4.05 | |||||

| 20 | Current | E.I. | 65 | 20.0 | 24.6 | 18.5 | 18.5 | 18.5 | 2.91 | |||

| E.M. | 92 | 23.9 | 12.0 | 25.0 | 27.2 | 12.0 | 2.91 | |||||

| Required | E.I. | 65 | 4.6 | 10.8 | 15.4 | 36.9 | 32.3 | 3.82 | 9.745 | 4 | 0.045 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leránoz-Iglesias, M.M.; Fernández-Morante, C.; Cebreiro-López, B.; Abeal-Pereira, C. Study on the Collaboration between University and Educational Centers Mentors in the Development of the In-School Education Placements in Official University Degrees Qualifying for the Teaching Profession: The Case of the University of Santiago de Compostela. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020104

Leránoz-Iglesias MM, Fernández-Morante C, Cebreiro-López B, Abeal-Pereira C. Study on the Collaboration between University and Educational Centers Mentors in the Development of the In-School Education Placements in Official University Degrees Qualifying for the Teaching Profession: The Case of the University of Santiago de Compostela. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(2):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020104

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeránoz-Iglesias, Martín Manuel, Carmen Fernández-Morante, Beatriz Cebreiro-López, and Cristina Abeal-Pereira. 2023. "Study on the Collaboration between University and Educational Centers Mentors in the Development of the In-School Education Placements in Official University Degrees Qualifying for the Teaching Profession: The Case of the University of Santiago de Compostela" Education Sciences 13, no. 2: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020104

APA StyleLeránoz-Iglesias, M. M., Fernández-Morante, C., Cebreiro-López, B., & Abeal-Pereira, C. (2023). Study on the Collaboration between University and Educational Centers Mentors in the Development of the In-School Education Placements in Official University Degrees Qualifying for the Teaching Profession: The Case of the University of Santiago de Compostela. Education Sciences, 13(2), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020104