Towards an Holistic Framework to Mitigate and Detect Contract Cheating within an Academic Institute—A Proposal

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Current institutional policies and procedures indicated that academic misconduct was identified and managed on an assignment-by-assignment basis. There was no transfer of knowledge about patterns and trends from one assignment to another, or from one unit to another, when identifying contract cheating cases. Therefore current approaches lacked sufficient evidence to form pattern analysis on students performance within a single unit or throughout a course. Pattern analysis is crucial for detecting contract cheating cases.

- While there are policies and procedures to handle academic integrity breaches, there is no comprehensive strategy or procedure to consistently handle contract cheating cases.

- Lack of specialised organisational units, such as an Academic Integrity Office (AIO), to handle contract cheating cases and ensure consistency within the institute needed to be addressed.

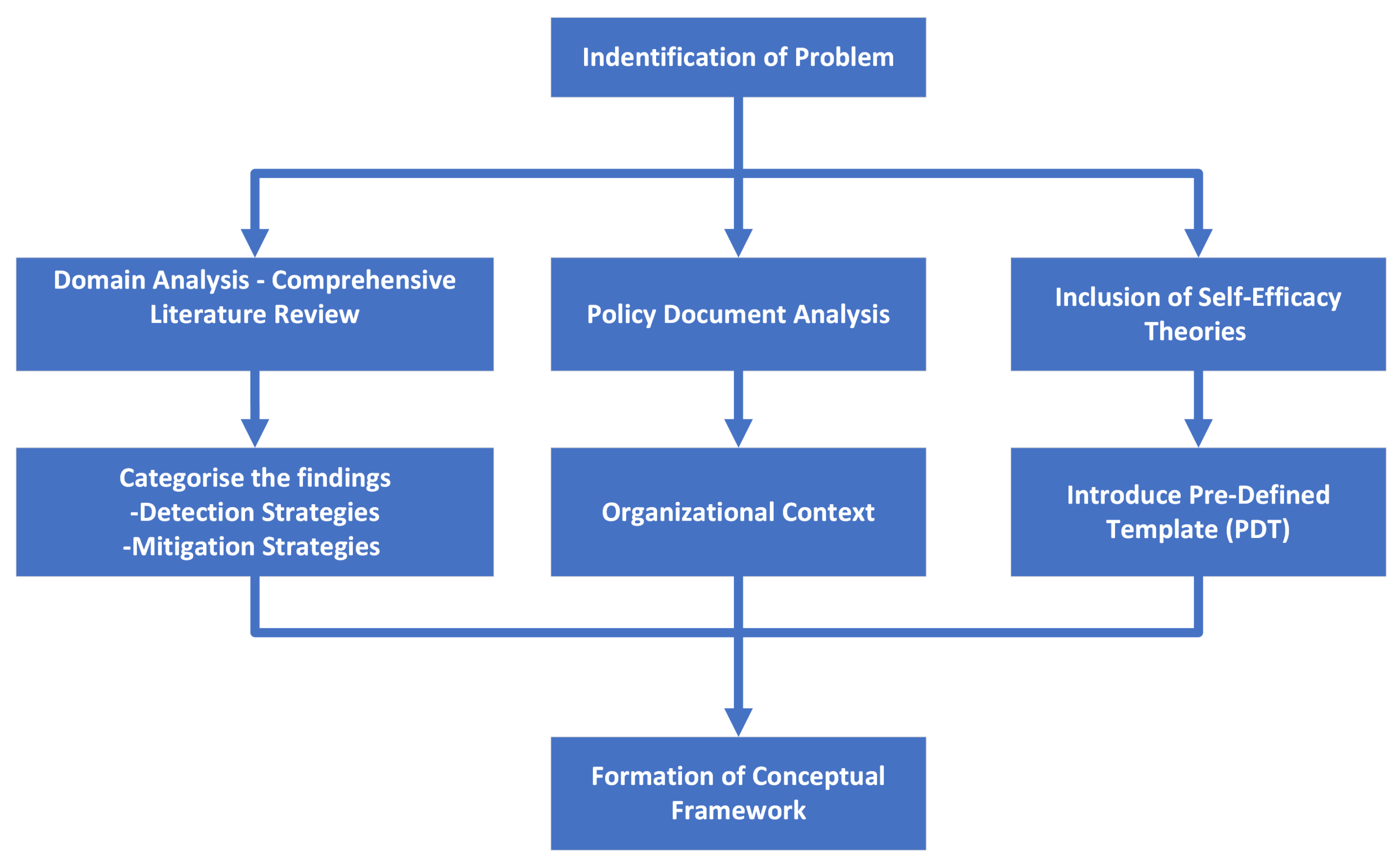

2. Determining Strategies to Detect Contract Cheating

2.1. Staff Upskilling

2.1.1. Staff Training to Improve Accuracy

- The time constraints faced by markers to complete grading and feedback. If markers evaluate students while students are taking their class, they need sufficient time to interview students to confirm the assignment was their own genuine effort. An adequate amount of time needs to be allocated for grading and further investigation to detect contract cheating, so that markers can apply various strategies if there are suspicious cases [12].

2.1.2. High-Profile Research to Educate Academics

2.2. Pattern Analysis

2.2.1. Software Analysis

2.2.2. Assessor Analysis

2.2.3. Specialised Administrative Staff Analysis

2.3. Assignment Design

3. Mitigate the Temptation to Cheat

3.1. Student Perspective

3.1.1. Formal Training to Improve Awareness

3.1.2. Informal Activities

3.1.3. Well-Equipped with Skills

3.2. Staff Perspective

3.2.1. Innovation in Curriculum and Assessment Design

3.2.2. Assignment Marking Strategies

3.3. Administrative Approaches

3.3.1. Academic Integrity Office (AIO)

3.3.2. IP Tracking and Other Technical Ways to Identify Contract Cheating

3.3.3. Allow Some Room for Late Submissions with Reduced Penalty

4. An Holistic Framework to Detect and Mitigate Opportunities for Contract Cheating

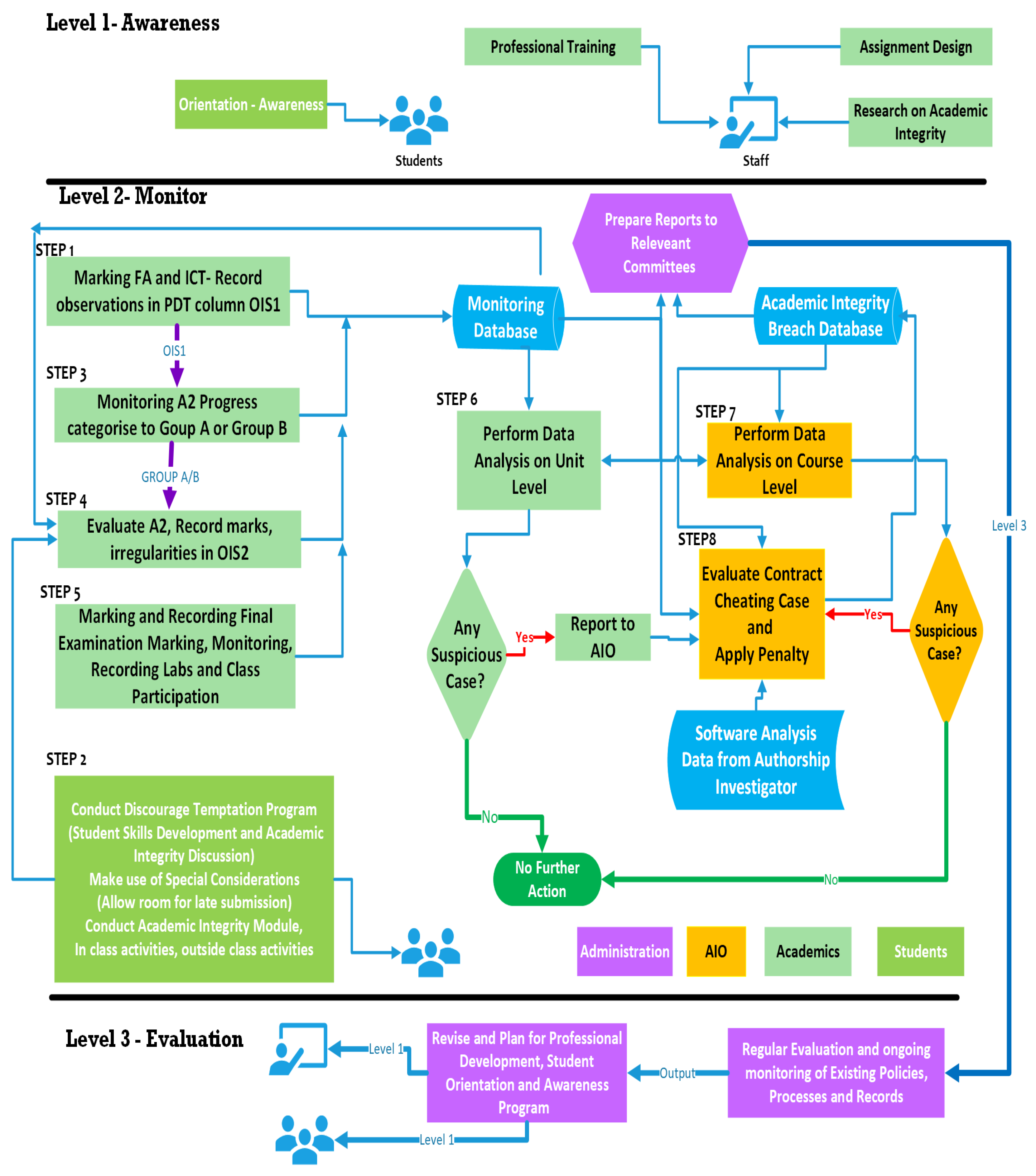

4.1. Three-Tier Framework (TTF)

- 1.

- Monitoring database: a centralised shareable database updated by academics for recording assignment marks, the progress of assignment monitoring, assessor input, and suspected activities,

- 2.

- Academic integrity breaches database: to record confirmed breaches by the AIO, and

- 3.

- Software analysis reports: obtained from authorship investigations or similar software from LMS and uploaded by specialised administrative staff in the AIO.

4.1.1. Level 1—Awareness

- Academic integrity including contract cheating

- Penalty associated with breaches

- Available student support services

- Support services available at Center of learning (CoL)

- Special consideration application process

- Inform new staff about contract cheating polices, procedures and services,

- Demonstrate trends, patterns and irregularities in potential cases with examples,

- Educate staff on assessment design, different evaluation techniques that can mitigate contract cheating cases, and

- Provide printed copies of institutional policies and a simple flow chart with the procedure they need to follow if they detect contract cheating.

4.1.2. Level 2—Monitor

- Ensuring that students are well equipped with the necessary skills and understand the assessment (Section 3.1).

- Allocating the last 30 min of laboratory classes to discussing A2 requirements until the due date.

- Recording student progress on A2 in PDT three times, as discussed in the next Step, and informing the student of this activity. This helps tutors to compare student performance and make students aware of the monitoring progress used for detection of contract cheating.

- Discussing the special consideration application process and other student support services available.

- Allowing late submission up to a specified number of days past the due date with a reduced penalty (Section 3.3.3).

- Preparing suitable assessment design by incorporating vivas, interviews or presentations for assignment evaluations (Section 2.3 and Section 3.2.2).

- Organising extra informal activities (Section 3.1) during the trimester, such as class discussions, lunch time activities, workshops, competitions, debates, research discussions, video presentations with real examples of penalties,

- Conducting sessions to enhance soft and hard skills to ensure students have the ability to do the assignment. (Section 3.1).

- Incorporating blended learning activities, such as pre-class quizzes, recorded lectures, and extra videos relevant to the topics to improve student confidence and, eventually, enhance enthusiasm for learning.

- Observe A2 progress and enter a numeric grade in the scale of one (1) (lowest) to 10 (highest) to record student’s progress on A2 (Section 2.2.2) three times. The numeric grade is recorded in PDT depending on assignment progress shown during the monitoring process.

- Calculate three-week average obtained by each student. The progress demonstration is considered successful if a student obtains five (5) or above as three-week average, otherwise it is considered unsuccessful.

- Categorise students into two groups: Group A and Group B. Tutors make an academic judgment and assign students to either Group A or Group B based on the following rule:Group A = Successful demonstration of A2 progress(three-weekaverage > 5) ANDno irregularities observed in OIS1 ANDgood class participationGroup B = Unsuccessful demonstration in class (three-weekaverage <= 5) OR irregularities observed in OIS1OR poor class participation

- The group of each student is recorded in PDT under the column “Group” before marking A2.

4.1.3. Level 3—Evaluation

5. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Works

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A2 | Assignment 2 |

| AIM100 | Academic Integrity Module 100 |

| AIO | Academic Integrity Office |

| CoL | Center of Learning |

| FA | Formative Assignment |

| ICT | In Class Test |

| LMS | Learning Management System |

| LOTE | Language Other than English |

| OIS | Observed Irregularities Stage |

| PDT | Pre-Designed Template |

| TEQSA | The Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency |

| TTF | Three-Tier Framework |

References

- Baird, M.; Clare, J. Removing the opportunity for contract cheating in business capstones: A crime prevention case study. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2017, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, P.M. How Common Is Commercial Contract Cheating in Higher Education and Is It Increasing? A Systematic Review; Frontiers in Education: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2018; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson, A.M. Detecting contract cheating in essay and report submissions: Process, patterns, clues and conversations. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2017, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lancaster, T. Commercial contract cheating provision through micro-outsourcing web sites. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2020, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, G.J.; McNeill, M.; Slade, C.; Tremayne, K.; Harper, R.; Rundle, K.; Greenaway, R. Moving beyond self-reports to estimate the prevalence of commercial contract cheating: An Australian study. Stud. High. Educ. 2021, 47, 1844–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, R.; Bretag, T.; Ellis, C.; Newton, P.; Rozenberg, P.; Saddiqui, S.; van Haeringen, K. Contract cheating: A survey of Australian university staff. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 1857–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, H.I.H.; Alhassan, A. Fighting contract cheating and ghostwriting in Higher Education: Moving towards a multidimensional approach. Cogent Educ. 2021, 8, 1885837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, P.; Sutherland-Smith, W. Can training improve marker accuracy at detecting contract cheating? A multi-disciplinary pre-post study. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harper, R.; Bretag, T.; Rundle, K. Detecting contract cheating: Examining the role of assessment type. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2021, 40, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awdry, R.; Newton, P.M. Staff views on commercial contract cheating in higher education: A survey study in Australia and the UK. High. Educ. 2019, 78, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahsan, K.; Akbar, S.; Kam, B. Contract cheating in higher education: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, R.; Luck, J.A.J.; Turnbull, D.; Pember, E.R. Back to the Classroom: Educating Sessional Teaching Staff about Academic Integrity. J. Acad. Ethics 2021, 19, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, J.A.; Chugh, R.; Turnbull, D.; Rytas Pember, E. Glitches and hitches: Sessional academic staff viewpoints on academic integrity and academic misconduct. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2022, 41, 1152–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.; Goodfellow, J.; Shoufani, S. Examining academic integrity using course-level learning outcomes. Can. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 2020, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nearing, E. Supporting the pivot online: Academic integrity initiatives at University of Waterloo. Can. Perspect. Acad. Integr. 2020, 3, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Race, P. The lecturer’s Toolkit: A Practical Guide to Assessment, Learning and Teaching; Routledge: South Oxfordshire, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, S.E.; Edino, R.I. Strengthening the research agenda of educational integrity in Canada: A review of the research literature and call to action. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2018, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wallace, M.J.; Newton, P.M. Turnaround time and market capacity in contract cheating. Educ. Stud. 2014, 40, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ouriginal. Plagiarism Detection Made Easy. 2022. Available online: https://www.ouriginal.com/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Blackboard. SafeAssign. 2022. Available online: https://www.blackboard.com/en-apac/teaching-learning/learning-management/safe-assign (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Cadmus. SafeAssign. 2022. Available online: https://www.cadmus.io/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- iThenticate. SafeAssign. 2022. Available online: https://www.ithenticate.com/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- University of Applied Science. Tests of Plagiarism Software. 2022. Available online: https://plagiat.htw-berlin.de/software-en/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Information Science Group. CitePlag—Citation-Based Plagiarism Detection. 2022. Available online: https://www.isg.uni-konstanz.de/projects/citeplag/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Turnitin. The New Standard in Academic Integrity. 2022. Available online: https://www.turnitin.com/products/originality/contract-cheating (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Businesswire. Turnitin Authorship Investigate Supporting Academic Integrity Is Released to Higher Education Market. 2022. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190313005128/en/Turnitin-Authorship-Investigate-Supporting-Academic-Integrity-is-Released-to-Higher-Education-Market (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Dawson, P.; Sutherland-Smith, W.; Ricksen, M. Can software improve marker accuracy at detecting contract cheating? A pilot study of the Turnitin authorship investigate alpha. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, D.C. Detection of Online Contract Cheating through Stylometry: A Pilot Study. Online Learn. 2020, 24, 142–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trezise, K.; Ryan, T.; de Barba, P.; Kennedy, G. Detecting Contract Cheating Using Learning Analytics. J. Learn. Anal. 2019, 6, 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, R.; Lancaster, T. Establishing a systematic six-stage process for detecting contract cheating. In Proceedings of the 2007 2nd International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Applications, Birmingham, UK, 26–27 July 2007; pp. 342–347. [Google Scholar]

- Bretag, T.; Mahmud, S. A model for determining student plagiarism: Electronic detection and academic judgement. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2009, 6, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonderwell, S.K.; Boboc, M. Promoting formative assessment in online teaching and learning. TechTrends 2013, 57, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelo, T.A.; Cross, K.P. Minute paper. In Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- Clare, J.; Walker, S.; Hobson, J. Can we detect contract cheating using existing assessment data? Applying crime prevention theory to an academic integrity issue. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2017, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, G.; Bretag, T.; Slade, C.; McNeill, M. Substantiating Contract Cheating: A Guide for Investigators. Australian Tertiary Education Quality Standards Agency. Available online: https://www.teqsa.gov.au/sites/default/files/substantiating-contract-cheating-guide-investigators.pdf?v=1588831095 (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Curtis, G.J.; Clare, J. How prevalent is contract cheating and to what extent are students repeat offenders? J. Acad. Ethics 2017, 15, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erguvan, I.D. The rise of contract cheating during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study through the eyes of academics in Kuwait. Lang. Test. Asia 2021, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.J. Academic integrity matters: Five considerations for addressing contract cheating. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2018, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newton, P.M.; Lang, C. Custom essay writers, freelancers, and other paid third parties. In Handbook of Academic Integrity; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 249–271. [Google Scholar]

- Bretag, T.; Harper, R.; Burton, M.; Ellis, C.; Newton, P.; van Haeringen, K.; Saddiqui, S.; Rozenberg, P. Contract cheating and assessment design: Exploring the relationship. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 676–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, P.; Sutherland-Smith, W. Can markers detect contract cheating? Results from a pilot study. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriadou, P.; Logan, D.; Daly, A.; Guest, R. The role of authentic assessment to preserve academic integrity and promote skill development and employability. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 2132–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, H.; Valtcheva, A. Promoting learning and achievement through self-assessment. Theory Into Pract. 2009, 48, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andrade, H.; Du, Y. Student responses to criteria-referenced self-assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2007, 32, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.A. The reliability, validity, and utility of self-assessment. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2006, 11, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Bretag, T. Academic Integrity. Available online: https://www.epigeum.com/courses/studying/academic-integrity/ (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Eaton, S.E.; Chibry, N.; Toye, M.A.; Rossi, S. Interinstitutional perspectives on contract cheating: A qualitative narrative exploration from Canada. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2019, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, Z.R.; Hemnani, P.; Raheja, S.; Joshy, J. Raising awareness on contract cheating–Lessons learned from running campus-wide campaigns. J. Acad. Ethics 2020, 18, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency. Resources. 2022. Available online: https://www.teqsa.gov.au/download-hub (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Ransome, J.; Newton, P.M. Are we educating educators about academic integrity? A study of UK higher education textbooks. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lombardini, C.; Lakkala, M.; Muukkonen, H. The impact of the flipped classroom in a principles of microeconomics course: Evidence from a quasi-experiment with two flipped classroom designs. Int. Rev. Econ. Educ. 2018, 29, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nagy, V.; Groves, A. Rational choice or strain? A criminological examination of contract cheating. Curr. Issues Crim. Justice 2021, 33, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Z. Statistical Analysis for Contract Cheating in Chinese Universities. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, B.; Saab, N.; van den Broek, P.; van Driel, J. The impact of formative peer feedback on higher education students’ academic writing: A Meta-Analysis. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 863–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicol, D. From monologue to dialogue: Improving written feedback processes in mass higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2010, 35, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Townley, C. Contract cheating: A new challenge for academic honesty? J. Acad. Ethics 2012, 10, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency. Academic Integrity Toolkit. 2022. Available online: https://www.teqsa.gov.au/commercial-academic-cheating (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- University, E.C. Contract Cheating: The Warning Signs. Available online: https://intranet.ecu.edu.au/_data/assets/pdf_file/0011/828776/Contract-Cheating-the-warning-signs-when-marking-Aug2019.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Bretag, T.; Mahmud, S.; Wallace, M.; Walker, R.; James, C.; Green, M.; East, J.; McGowan, U.; Patridge, L. Core elements of exemplary academic integrity policy in Australian higher education. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2011, 7, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretag, T. Good Practice Note: Addressing Contract Cheating to Safeguard Academic Integrity; Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency: Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- De Maio, C.; Dixon, K. Promoting academic integrity in institutions of higher learning: What 30 years of research (1990–2020) in Australasia has taught us. J. Coll. Character 2022, 23, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C.; Zucker, I.M.; Randall, D. The infernal business of contract cheating: Understanding the business processes and models of academic custom writing sites. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2018, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendinning, I. Aligning academic quality and standards with academic integrity. In Contract Cheating in Higher Education; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.; Rowell, G.; Badge, J.; Green, M. The benchmark plagiarism tariff: Operational review and potential developments. In Proceedings of the 6th International Plagiarism Conference, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 16–18 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, P.; Rowell, G. Benchmark Plagiarism Tariff. Available online: http://marketing-porg-statamic-assets-us-west-2.s3.amazonaws.com/main/Tennant_benchmarkreport-(1).pdf (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- International Center For Academic Integrity Conference. Available online: http://thomaslancaster.co.uk/blog/international-center-for-academic-integrity-conference-2019/ (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Slade, C.; Rowland, S.; McGrath, D. Addressing Student Dishonesty in Assessment Issues Paper for UQ Assessment Sub-Committee; Institute for Teaching and Learning Innovation, University of Queensland: St. Lucia, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Pers. Psychol. 1997, 50, 801. [Google Scholar]

- De Maio, C.; Dixon, K.; Yeo, S. Responding to student plagiarism in Western Australian universities: The disconnect between policy and academic staff. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2020, 42, 102–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bretag, T.; Mahmud, S. A conceptual framework for implementing exemplary academic integrity policy in Australian higher education. In Handbook of Academic Integrity; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 463–480. [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty, C.; Lang, C.; Usdansky, M.; Kanani, M.; Jamieson, M.; Gallant, T.B.; George, V. Institutional Toolkit to Combat Contract Cheating; International Center for Academic Integrity, University of Alabama: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Assessment Task | Due Date | Supervised |

|---|---|---|

| Formative Assignment (FA)-(5%) | Week 3 | No |

| In Class Test (ICT)-(10%) | Week 5–8 | Yes |

| Assignment 2 (A2)-(25% to 30%) | Week 11 | No |

| Class Participation and Contribution-(15%) | Weekly | No |

| Final Examination-(40–50%) | Week 13–14 | Yes |

| Marks | Assessor Input | Progress—A2 | Marks | Assessor Input | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | ICT | OIS1 | Comment | A2 | A2 | A2 | Group | A2 | OIS2 | Comment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guruge, D.B.; Kadel, R. Towards an Holistic Framework to Mitigate and Detect Contract Cheating within an Academic Institute—A Proposal. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020148

Guruge DB, Kadel R. Towards an Holistic Framework to Mitigate and Detect Contract Cheating within an Academic Institute—A Proposal. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(2):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020148

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuruge, Deepani B., and Rajan Kadel. 2023. "Towards an Holistic Framework to Mitigate and Detect Contract Cheating within an Academic Institute—A Proposal" Education Sciences 13, no. 2: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020148