1. Introduction

Over the last decade, distributed leadership (DL) has increased in popularity worldwide (see, for example [

1,

2,

3]). According to [

4], a distributed viewpoint frames leadership practice in a specific way; it is seen as the result of the interactions between school leaders, followers, and their environment. The literature indicates that if principals distribute leadership appropriately among stakeholders such as the management team, teachers, and students, school performance as determined by the effectiveness of its education and the academic progress of its students tends to improve [

5,

6,

7,

8]. A growing body of research has analysed distributed leadership and its association with quality of education [

9], teacher job satisfaction [

10,

11], organisational commitment [

12,

13,

14], organisational change [

15], and school climate [

16], across diverse countries. However, authors like [

17,

18] highlighted the importance of contextual and cultural influences in the implementation of school leadership policy. Specifically, Ref. [

19] (p. 2) emphasised the importance of country context for distributed leadership, concluding that “distributed leadership varies by leadership function and appears to be influenced by country education policy”. Due to these cultural differences in leadership processes [

20,

21,

22], it is important to investigate further the equivalence of leadership concepts across countries. In other words, we need to test whether the definition and conceptualisation of such leadership constructs are the same across diverse cultures.

International large-scale assessments (ILSAs) are designed to investigate the relationship between various characteristics of teachers, principals, and schools by using background questionnaires. Background questionnaires are questionnaires that include a broad range of questions for school teachers and principals. The Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS, 2018) is one of the most widespread ISLAs and is conducted by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) across the world [

23]. Although TALIS collects data on different leadership styles and their association with different aspects of school- and teacher-related factors, there still appear to be validity issues in the cross-cultural comparison of these theoretical constructs [

24,

25]. To be able to interpret survey scores acquired from different cultural groups in the same way, we need to establish cross-cultural comparability using empirical data. This is known as measurement equivalence or invariance.

A key reason why measurement invariance is often violated in ILSAs is the assumed universality of attitudinal constructs across cultures. Attitudinal constructs may not be comparable across cultures since cultural factors might shape how a background questionnaire is interpreted and, accordingly, how it is responded to [

26]. For this reason, studies of principals using international large-scale assessments such as TALIS face potential difficulties in making cross-cultural comparisons [

23].

Specific leadership strategies might work effectively in some countries but not others because of the diversity of culture across contexts. For example, principals who work in socioeconomically disadvantaged schools might engage other stakeholders for leadership activities less frequently than principals who work in more affluent schools [

27]. In this sense, school contextual factors, country characteristics, and educational systems may influence the attitudes and strategies of principals because of the diverse educational system-level characteristics and policies [

28]. It is important to be able to make comparisons of the mean of theoretical constructs (e.g., distributed leadership) across countries to understand their relationship with student outcomes and teacher-related factors in multi-country analysis. There are, however, very few studies that have tested for invariance in order to compare the latent factor means of school principal constructs across education systems or countries [

29,

30].

In this study, we used a relatively novel and recent approach known as Alignment Optimisation [

31,

32]. We use this to compare latent means, across countries, of the “Distributed Leadership Scale”, the most studied leadership concept of the last decade [

1]. We use distributed leadership scores from the perspective of principals from The Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS, 2018) [

23]. The use of alignment optimisation is a strength of this study, both theoretically and methodologically, due to the greater robustness of analysis when compared to traditional methods of comparing latent means across groups such as Multi-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis (MGCFA). This study should be seen as a starting point for improving international comparison through finding equivalent scores (measurement invariance) across countries for the “Distributed Leadership Scale”. The study results provide valuable information to improve the measurement of concepts such as principal school leadership and caution the inferences drawn from international comparisons. National and local governments and the organisations that carry out international assessments could be the primary beneficiaries of the procedures and conclusions developed in this research.

In the following section, we provide a brief conceptual summary of distributed leadership and its conceptualisation in the context of the OECD’s TALIS study. Later, we present an overview of measurement invariance and empirical research on measurement invariance of teacher and leadership constructs in ILSAs, mainly using TALIS data. Then, we introduce our sample, variables, analytical strategy, and present our findings. Lastly, we discuss our results and present implications for both policymaking and future research.

3. Techniques of Testing Measurement Invariance

The primary purpose of TALIS is to produce internationally comparable background information regarding teachers and their teaching practices, and principals and school management, which directly or indirectly influence student learning and academic achievement [

44]. However, cross-cultural comparability of the constructs derived from TALIS’s questions might be problematic. This is due to the lack of evidence of the generalisability of the instruments across countries. Participants from different countries and cultures may understand and interpret questions differently, therefore, affecting cross-country comparability [

45]. To address the issue of cross-country comparability, the measurement invariance of instruments used in TALIS should be investigated [

46]. To be able to make the mean comparison of these constructs across countries, measurement invariance should satisfy the more restrictive level (scalar invariance), though this is often difficult to achieve.

TALIS experts evaluate measurement invariance within the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) framework [

24,

47]. Measurement invariance implies that using the same questionnaire in different groups (e.g., countries or at various points in time) does measure the same theoretical construct in the same way and, therefore, that the resulting scores can be interpreted in a comparative fashion [

48]. Most tests of measurement invariance include configural, metric, and scalar steps [

29,

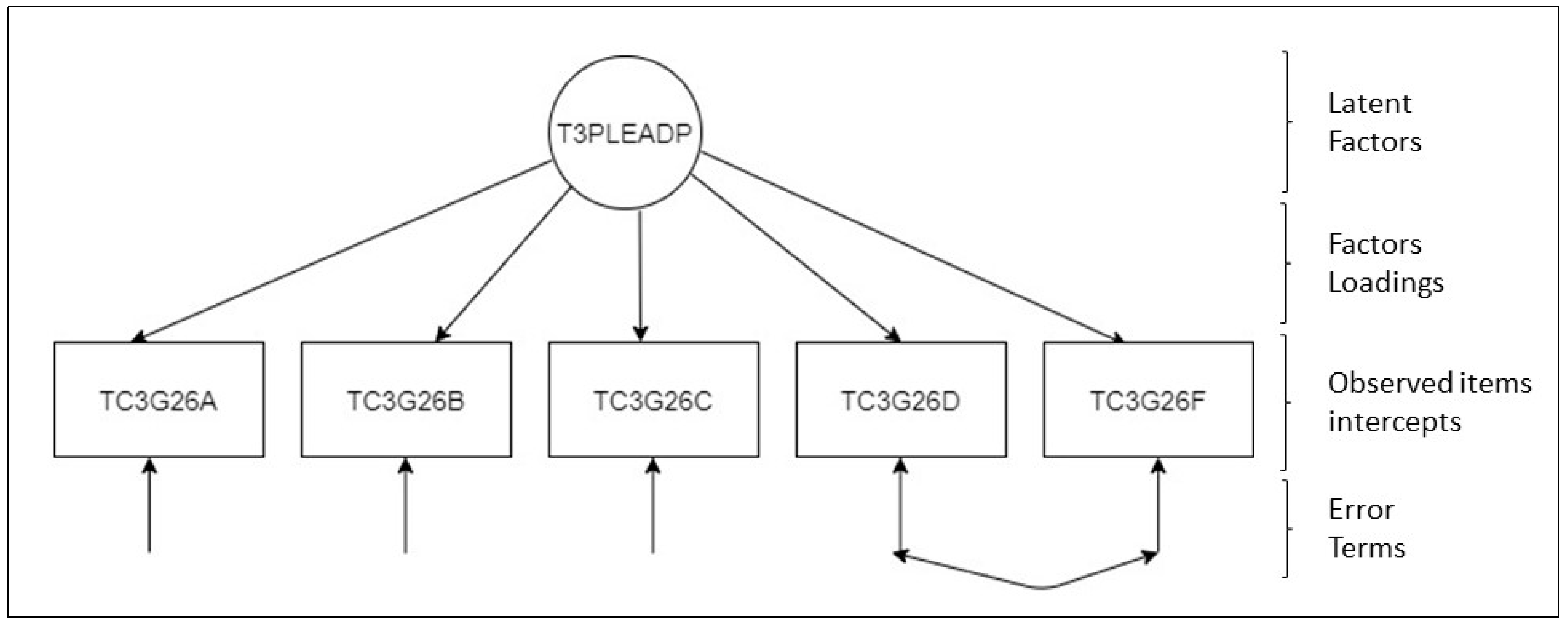

46]. Configural invariance or structural equivalence implies that the same model holds for all the groups. Metric invariance implies that the factor loadings are the same across the groups and, therefore, comparing unstandardised regression coefficients and/or covariances across groups is allowed. Finally, scalar invariance or full score equivalence implies that the intercepts are the same across all countries being compared and, therefore, the latent factor means can be compared (see

Figure 1 for a graphical representation of these concepts). However, reaching this level of invariance is almost always unrealistic in the context of ILSAs such as TALIS. Therefore, latent mean comparisons of constructs such as principal distributed leadership across countries should be made with caution as they do not reach scalar-level invariance [

23].

When the scalar invariance level is not reached, a partial invariance method can be used that increases the invariance level of the model by making some adjustments. This can be used instead of completely sacrificing the model. The partial invariance approach contains the adjustment in modification indices by stages in which the items in the construct with most invariance are first detected and later constrained equally across the groups for the latent mean comparison of the model to be tested, and the items with non-invariance are freely estimated across the groups [

49]. However, the partial measurement invariance approach can be laborious. This is mainly because once there are many groups or items within each factor in the model, the model requires manual adjustment according to the modification indices [

31]. Moreover [

50] suggested that the partial invariance method should not be preferred when many indicators are found to be noninvariant.

Alignment optimisation, a relatively new and novel approach, has been recommended over traditional measurement invariance approaches for the comparison of latent averages across diverse groups [

31,

32]. The process of alignment optimisation first determines the most non-invariance items. Later, those items’ influence on the scalar non-invariance of the measurement model is optimised iteratively. Thus, the minimum scalar non-invariance is obtained to make average comparisons of the measurement model [

32]. This technique can be employed to compare unobserved averages across diverse groups and rank the countries with the highest and lowest averages in the measurement model (in the construct).

However, in the literature, relatively few studies employ alignment optimisation in the context of International Large-Scale Assessments (ILSAs) [

26,

51,

52]. Although, some examples include the following. Ref. [

51] analysed the measurement invariance of the CIVED99 and ICCS 2009 data’s adolescents’ support for an immigrants’ rights construct using alignment optimisation across 92 groups (by country, cohort, and gender) and found that unbiased group comparisons were possible despite the presence of significant non-invariance in some groups. Ref. [

52] compared the latent means of a job satisfaction scale using alignment optimisation across 48 countries using TALIS 2018 data. Ref. [

26] compared the TIMSS’ 2015 teacher-related characteristics using alignment optimisation and argued that these constructs could be validly compared across educational systems, and a subsequent comparison of latent factor means compares differences across the groups.

There are relatively few studies on the comparability of the distributed leadership concept across countries. Recently, Printy and Liu [

19] and Liu [

28], using TALIS 2013 data across 32 countries, found that country and contextual factors and educational policies in each education system may influence distributed leadership activities and may be associated with how leadership is distributed within schools. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have used alignment optimisation to study school principal constructs such as the principal distributed leadership scale. We see alignment optimisation as a more appropriate method for making cross-cultural comparisons than traditional methods such as MGCFA. For this reason, we use alignment optimisation [

31,

32] to compare latent means of the “distributed leadership scale” from the perspective of principals. We can then, to some extent, compare our results to those of Printy and Liu [

19] and Liu [

28] and other related studies in the literature.

The scope of this study is the examination of how principals’ perceived distributed leadership styles differ across countries. In this study, in our conceptualisation of distributed leadership, we address the subordinates’ roles from the perspective of principals. We conceive countries as a unit of analysis, in the sense that scores may differ between schooling systems and cultural contexts [

21,

22,

53]. Therefore, in this study, we aim to test the cross-cultural comparability of principals’ perceived distributed leadership.

7. Discussion

Distributed leadership is understood as a way to include teachers, students, parents. and other stakeholders in decision-making processes, thus increasing schools’ organisational capacity and students’ outcomes. The current study adds to the literature by providing information on cross-country mean comparisons of distributed leadership. Few studies have investigated this, all of which have used a more restricted traditional measurement invariance approach compared to the alignment optimisation method. Using TALIS 2018 data from 40 countries, the results verify that we can validly and reliably compare levels of distributed leadership, as perceived by principals, between countries. In the traditional measurement invariance approach (MGCFA), the principal-perceived distributed leadership construct only met metric-level invariance, which means that the score means cannot be reliably compared across countries. Consequently, it is necessary to improve the measurement of this construct to allow for cross-cultural comparisons, which is particularly important in the context of International Large-Scale Assessments (ILSAs).

In doing so, this study employed the alignment optimisation method to address group mean comparisons considering that the principal-perceived distributed leadership construct did not satisfy with scalar invariance. This indicated that the latent factor mean of this construct cannot be comparable across countries using a traditional measurement invariance approach (MG-CFA). However, the results of the alignment optimisation approach yield a comparable pattern across countries. Our approach enables us to obtain the most optimal measurement invariance form in evaluating comparability considering the parameters of latent variable indicators of the partial invariance [

31,

32]. Considering the configural-level invariance model as a basis, this study uncovered that there were many variables in the principal distributed leadership construct and countries with significant non-invariance. This method allows us to see the details in the invariance model such as the underlying assistance to most scalar non-invariance as well as offers the opportunity to examine each item separately in detail (items’ factor loadings and intercepts).

Although there are few studies on cross-cultural comparison of the perceived distributed leadership of school principals, the findings of our study are comparable with some findings of Printy and Liu [

19] and Liu [

28]. Our findings corroborate those of Printy and Liu’s [

19] study, to some extent. They found that Korea, Serbia, Bulgaria, Denmark, and Latvia have the highest levels of collaboration between teachers and principals in the organisational decision-making process (see page 310) using TALIS 2013 data. Our study found that Korea has the highest levels of distributed leadership among the 40 countries participating in TALIS 2018. We also found that Latvia ranked highly. Unlike Printy and Liu’s [

19] study, however, we found that Colombia, Shanghai (China), Lithuania, Georgia, the Russian Federation, Estonia, Romania, and Alberta (Canada) have some of the highest levels of distributed leadership, ranked from two to nine, respectively.

Our results can also be explained by other school characteristics. For example, in the two countries with the highest levels of distributed leadership (Colombia and Korea), more than 80% of principals reported that parents and/or guardians are represented in their school management team. Moreover, in Colombia, more than 80% of principals reported that students are also involved in their management team [

44]. In contrast, in the two countries with the lowest levels of distributed leadership (Argentina and Japan), principals tended to be more engaged in direct instructional activities, with these two countries being among those with the highest proportion of principals reporting that they are involved in direct instructional leadership activities (ibid.).

There is a need to further investigate countries that score highly on distributed leadership to understand what they are doing differently to enable greater distribution in leadership. One way of explaining why Shanghai (China) has higher levels of distributed leadership is that teachers might receive greater support from their principals for participating in school decisions and that this support may also extend to students, students’ parents, and other stakeholders.

Similar to Printy and Liu [

19], we find that Japan, Israel, and the Netherlands have the lowest mean scores for distributed leadership. Schools in these countries tend to have a traditional authority structure, where principals take on most of the decision-making responsibility. Our findings support this view with Japan, the Netherlands, and Israel being ranked lowest on levels of distributed leadership. For example, in the case of Japan, following the same line of reasoning of Printy and Liu [

19] and Liu [

28], we posit that principals in these countries are required to take responsibility for decisions and hierarchical pressures prevent teachers from influencing school decisions. We might be able to extend this interpretation to other stakeholders.

The unique contribution of our study is to precisely rank countries according to their mean distributed leadership scores for school decision-making exercises. We restrict our focus, however, only to the “organisational decision making” component of distributed leadership. This is unlike Printy and Liu [

19], who analysed the four components of distributed leadership and used their findings to categorise countries into four quadrants of distributed leadership. However, when compared to findings from TALIS 2013 (Printy and Liu [

19]) and TALIS 2018 (our study), we find some similar results. This is despite the use of different analytical approaches. For example, Korea was among the highest level of distributed leadership in school decisions in 2013 and it was the highest level country in distributed leadership in school decisions in 2018. This shows that over the five-year period, Korea has more or less maintained its position in terms of levels of distributed leadership in school decision making. In this five-year period, different countries have moved towards the top of the ranking of distributed leadership such as Colombia, Shanghai (China), Lithuania, Georgia, the Russian Federation, and Estonia. For example, although Printy and Liu [

19] found that Estonia had one of the lowest distributed leadership levels in TALIS 2013, this study, using TALIS 2018 data, found that Estonia ranked seventh for levels of distributed leadership in school decision making. It would therefore be of interest to investigate what changes have occurred in the Estonian educational system that have led to an increase in the levels of distributed leadership.

Although the results of this study contribute to the literature as the first robust evidence for the possible comparability of the principal-perceived distributed leadership construct, the principal-perceived distributed leadership construct did not give us clear evidence to cluster countries according to geographical regions or continents as suggested by Liu [

28]. We can only observe, from

Table 6 Nordic European countries (Finland, Norway, and Sweden) situated close to each other, in the ranks of 24, 25, and 27, respectively. Future research could examine these similarities and differences between countries in a comprehensive way, for example, drawing on qualitative case studies.

Furthermore, the findings of this study provide a framework for comparing one country with another based on the average principal distributed leadership. We believe that the findings of this contribution to the literature will have implications for government agencies, ministries of education, policymakers, research centres, and other stakeholders (e.g., practitioners in classrooms) in education. Our results provide robust empirical criteria to compare the levels of principals’ distributed leadership across countries.

When making decisions about how to allocate leadership responsibilities to achieve the best results, practitioners need evidence to support their decisions. This study closes the evidence gap by demonstrating how leadership responsibilities are carried out by multiple leaders rather than a single one and how the process may differ between schools and nations. Such findings inspire more experimental investigations on DL behaviours in various nations because the prevailing data, which were mostly produced in the United States and the United Kingdom, might not apply to nations with diverse cultural alignments. This, in turn, can help decision makers to identify those education systems that have contextual, cultural, or historical similarities to their own in order to carry out in-depth studies that allow them to learn from each other. We believe that this kind of in-depth analysis can assist in the development of educational institutions and practices. The perceptions of principals’ distributed leadership are important to schools’ organisational capacity, as well as for student outcomes (see, for example [

5,

6,

7]) and it has been argued that it can contribute to school effectiveness and improvement.

8. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The purpose of this study was to test the validity of latent mean comparisons of principal distributed leadership across different countries. Given the number of countries and the diversity of the sample in TALIS worldwide, it is almost impossible to reach the scalar level of invariance which is required for multiple groups mean comparison. However, implementing a relatively new and practical alignment optimisation approach [

31,

32], depending on an approximate scalar invariance, enables us to compare the means of the principal-perceived distributed leadership scale across 40 countries and economies. Korea was found to have the highest levels of distributed leadership in school decisions from the perspective of principals, whereas Japan was found to have the lowest levels of distributed leadership. Furthermore, the findings of this study allow us to make comparisons between one country and another as these types of findings are relatively scarce in previous research.

Although this study used large-scale international data, a clear theoretical framework, and a relatively new efficient alignment optimisation method, there are important limitations to consider. First of all, researchers should be careful and cautious in their interpretation of findings. This is because the study uses principals’ self-reported data, which may be subject to common self-report data biases [

67]. Therefore, for future studies, student, teacher, and other stakeholder opinions should also be taken into consideration for a more robust analysis. Another limitation of this study is the impossibility of combining two scales that measure the other components of distributed leadership in the TALIS 2018 questionnaire (Printy and Liu [

19]) using the alignment optimisation approach. We chose to only consider the “organisational decision making” component of distributed leadership. This is because it is not suitable to combine multiple scales when using alignment optimisation.

Another limitation of this study is that we analysed only one component of distributed leadership: organisational decision making. Distributed leadership, however, is an extensive and multidimensional concept that consists of dimensions such as setting school direction, developing people, redesigning organisational structure, and managing instructional practice. Our study is therefore limited by the fact we do not measure all dimensions of distributed leadership as it is typically conceived in the literature. Further studies should attempt to include all these dimensions.