2.1. Context

The “Intercultural Buddies Project” was officially registered as a COIL project at its hosting HEI, the University of Aveiro, and implemented within the English Language and Business Communication course, a level B2.2 (Common European Framework of Reference for Languages) course primarily directed at 2nd-year students (19–20 years old) taking the undergraduate degree in Office Management and Business Communication, awarded by the UA.

The Office Management and Business Communication undergraduate degree aims to train qualified professionals capable of assisting and providing executive assistance to public and private organizations, at both national and international levels. Due to the multi- and interdisciplinary training they receive, graduates are prepared to manage complex communication flows in different languages and across different cultural settings. The English Language and Business Communication (ELBC) subject aims, on the one hand, at consolidating and improving previously acquired language skills, and, on the other hand, at promoting activities that are consistent with students’ future professional needs. By the end of the course, which is built around four main sections—(1) communication; (2) intercultural communication; (3) intercultural sensitivity in business communication; and (4) business communication: telephoning and socializing (in cross-cultural contexts)—students are expected to: (i) describe various types of communication and recognize contextual linguistic variation; (ii) produce oral and written texts, consistent with and appropriate to different contexts of business communication; (iii) identify dysfunctional communicative situations in intercultural contexts; (iv) develop research in the field of intercultural communication; (v) present and critically analyze the results of this research; and (vi) optimize the production of oral and written statements in a business context through the use of online tools [

12].

For this project, ELBC students enrolled in the academic year 2021/22 were challenged to write a “Country and Culture Profile Report” in the form of a 10-page research paper. Following the APA format and citation guidelines was a requirement, and, after submitting their papers, students also had to prepare an oral presentation of their assignments.

Similar cultural research activities had been implemented in previous years, namely, through the project “Building Cultural Bridges in the Classroom”, an initiative that aims at involving students in the development of their linguistic and intercultural skills in more active and motivating ways, such as direct contact with peers from different cultures, in this case, with volunteers from the European Solidarity Corps visiting the city for a period of time [

13]. As a result of the limitations imposed by the global pandemic, in the fall of 2021, the ELBC teacher sought an alternative to the previously successful cross-community interactions and opted for a COIL project—an internationalization strategy that, at the time, was very much encouraged by the UA as a possible response to the disruptive circumstances we were facing.

2.2. Objectives, Methodological Options, and Educational References

This activity was designed to be a student-centered activity based on research work and online collaboration with the main aim of developing English communication skills and intercultural competence. In addition to fostering students’ language and intercultural competence, profiling another (very different) country also aimed at developing students’ research and academic writing skills, communication and collaboration skills in international teams, digital skills, organization and work methods, time management, creativity, active learning and adaptability, etc.—all important global skills for the 21st-century labor market [

5,

14,

15,

16,

17]. The main advantage for the students would be the opportunity to consolidate their language and intercultural communication skills through peer interaction and collaboration at an international level; due to its interactive and real/concrete testimonial nature, teachers expected it to be a different and potentially more motivating and enriching learning experience at both academic and personal levels. This was also an opportunity for both groups to reflect upon their own cultures, values, principles, and identities, which were then reciprocally shared with/acknowledged by their peers.

The objectives of the activity and methodology adopted sought to align with several frameworks, guidelines, and recommendations issued by relevant world organizations. The Council of Europe, for example, highlights the key role of languages not only as key factors for social inclusion and workforce mobility, but also as fundamental skills that contribute to a more cohesive and culturally enriched Europe [

18]. Particularly relevant in this context is the Council’s

Recommendation on a Comprehensive Approach to the Teaching and Learning of Languages [

18], in which EU member states are encouraged to continue to promote the acquisition of foreign-language competencies in at least one other European language up to a level that allows citizens to use the language effectively for social, learning, and professional purposes. Language skills are, therefore, perceived as valuable assets that provide competitive advantages for both companies and employees, as well as a better understanding of other cultures, thus contributing to the development of citizenship and democratic competence. Relatedly, in its

Competences for democratic culture. Living together as equals in culturally diverse societies [

19], the Council of Europe also underlines the importance of language and communication as critical competencies for an individual’s effective participation in society.

Alongside the importance of mastering foreign languages, gaining insight into other cultures is yet another fundamental life skill that opens up a world of job opportunities for our graduates. This need to develop intercultural competencies is highlighted by entities such as the United Nations in its

2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

20], which calls for the promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship, and appreciation of cultural diversity (Sustainable Development Goal 4—Education). The Council of Europe [

19] also advocates that appreciating cultural diversity is a fundamental core value, as well as responsibility, respect, and openness to different cultures, world views, and practices, which are also inscribed as significant attitudes. UNESCO, too, reinforces the importance of learning to (i) study, inquire, and co-construct together; (ii) collectively mobilize; (iii) live in a common world; and (iv) attend and care [

21]. All in all, in the face of change, complexity, and uncertainty, knowledge and social skills to support effective participation in a global society, as well as an understanding of the Other and a sense of respect for pluralism/diversity, are absolutely critical.

An important reference tool for education and training stakeholders, the European Union’s

Recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning [

6] encourages member states to prepare their citizens for a world that is ever more diverse, mobile, digital, and global. Being able to quickly adapt to changing labor markets, being active citizens, and being willing to learn at all stages of life are some of the aspects that call for a change in mindset. Among the different key competencies identified by the European Union, our project sought to contribute to five in particular: (i) literacy competence; (ii) multilingual competence; (iii) digital competence; (iv) cultural awareness; and (v) personal, social, and learning-to-learn competence. Absolutely relevant in the context of collaborative work in which this activity was set, (v) is defined by [

6] as “the ability to reflect upon oneself, effectively manage time and information, constructively work with others, remain resilient and manage one’s own learning and career. It includes the ability to cope with uncertainty and complexity, learn to learn, support one’s physical and emotional well-being, empathize and manage conflict”. Often coined as soft skills, i.e., any skill or quality that can be classified as a personal characteristic that shapes how an individual communicates and relates with others, personal and interpersonal skills, such as autonomous learning skills, analytical and critical thinking skills, empathy, flexibility and adaptability, cooperation skills, conflict-resolution skills, and organization and time management, are all-important, highly transferable skills that can be applied in nearly every work setting [

13,

19].

Connectedly, the

OECD Learning Compass 2030 [

5] emphasizes that empathy and mutual respect, curiosity, collaboration, awareness, and openness to experience are some of the skills associated with academic success and better preparation for the challenges of an ever more global and interconnected world. This view is aligned with the World Economic Forum [

14] and its vision for Education 4.0, which reimagines education as an inclusive, lifelong experience, with problem solving, collaboration, and adaptability as the three critical skills that play a central role in each student’s personal curriculum.

In this same vein but in terms of language and pedagogy research, recognition is also given to the integration of global skills into the classroom. For example, the authors of [

22] identify communication and collaboration, creativity and critical thinking, intercultural competence and citizenship, and emotional regulation and wellbeing, as well as digital literacies, as fundamental interdependent skills clusters that should be included in the preparation of future graduates for the challenges of the global market.

All in all, transferable skills (or transversal skills, life skills, soft skills, people skills, 21st-century skills, or socio-emotional skills—the set of synonymous designations is rather vast) are those that allow young people to become agile, adaptive learners and citizens equipped to navigate personal, academic, social, and economic challenges [

5]. Corroborating this idea, there is a growing literature indicating that many employers are now prioritizing soft skills during hiring [

23,

24]. For example, a recent survey of more than three thousand companies from across the globe [

25] reports that dependability, teamwork/collaboration, problem solving, and flexibility are currently the most in-demand skills; additionally, the authors of [

26] also point out that critical thinking, communication, and creativity are the soft skills employers have the most trouble finding. Ultimately, soft skills are what help build strong team relationships, which, in turn, lead to higher productivity levels and successful creativity and collaboration, thus contributing to an organization’s success.

The ELBC teacher’s option for a student-centered activity based on cross-border collaborative work aims precisely to enhance some of these in-demand skills and therefore contribute to filling a gap identified in the current labor market.

2.3. Project Description, Stages, and Timeline

In order to produce their “Country and Culture Profile Reports”, ELBC students were invited to interact with a group of international students from the University of the Thai Chamber of Commerce (UTCC) who acted as their “local consultants” or “intercultural buddies”, who would provide different items of Thai cultural information which the UA students could use in writing their reports.

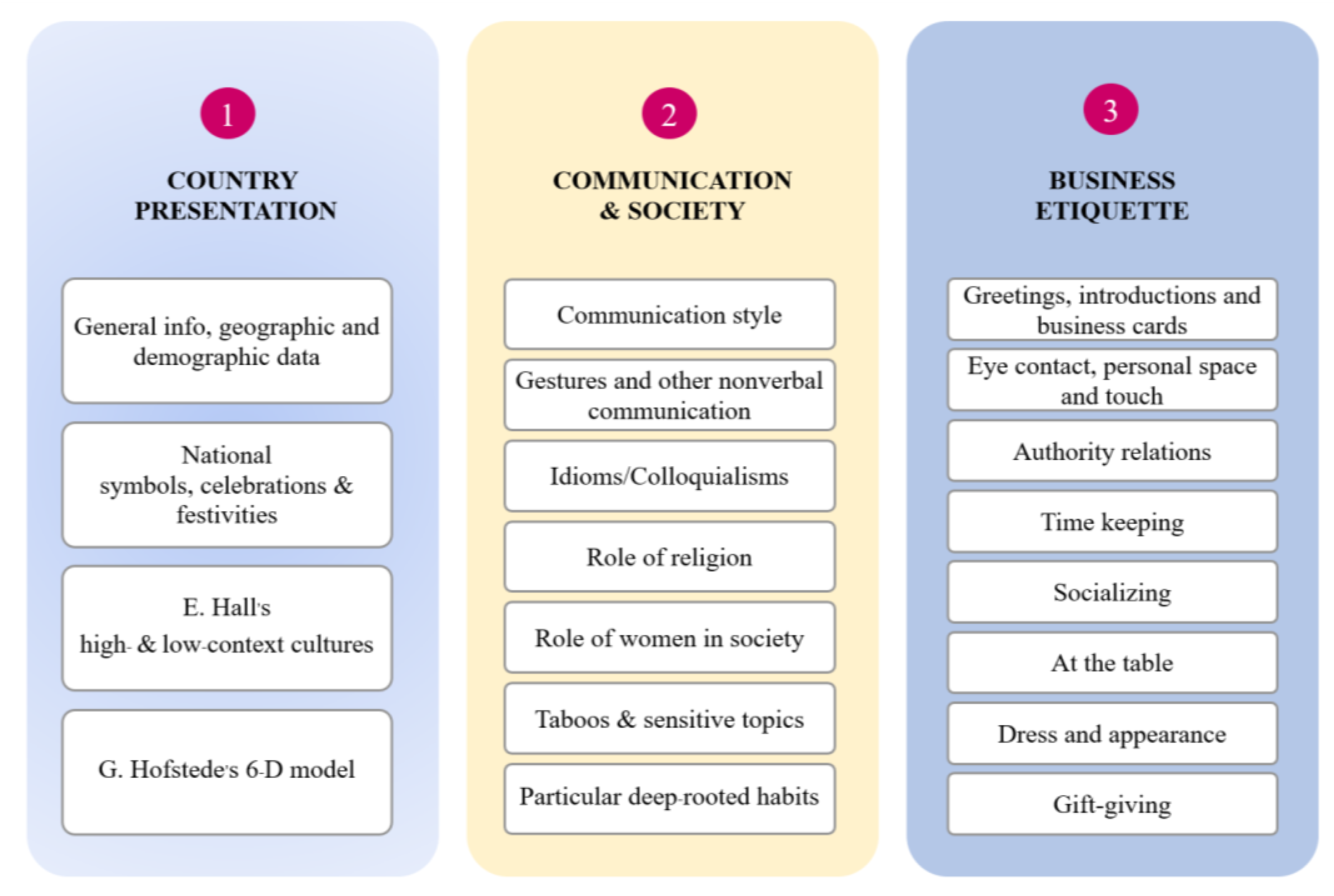

The project involved 46 participants of eight different nationalities—21 students at the University of Aveiro from Portugal, Brazil, Latvia, Spain, and Germany, and 25 students at UTCC from Thailand, Myanmar, and Cambodia. This interaction not only allowed for a context in which the students could practice their communication skills, it also provided the necessary internal insight required for them to more adequately describe each other’s countries and cultural backgrounds. Eight out of the ten groups wrote about Thailand; the remaining two groups researched and wrote about Cambodia and Myanmar, respectively. As a scaffolding strategy to help students focus their attention on more specific aspects, a list of relevant topics to research was provided (

Figure 1).

The theoretical framework underpinning topics 1.4 and 1.5—Geert Hofstede’s cultural dimensions model and Edward Hall’s high- and low-context cultural framework—is part of the course syllabus and had been extensively discussed in class. Above all, the main focus was not so much the information or aspects that are easily seen/found by non-natives, i.e., the explicit manifestations of students’ national cultures, but rather the students’ reflections upon their own thought patterns and underlying beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors, that is to say, all those specific traits that are implicit, or―to use the cultural iceberg metaphor—those characteristics that are underneath the surface and therefore out of conscious awareness. When interacting/working across cultures, it is precisely this deeper level of culture that leads to difficulties or communication problems that intercultural training seeks to help overcome.

The activity was developed over five main stages: (i) initiation, (ii) planning, (iii) implementation, (iv) execution and progress monitoring, and (v) closing.

Figure 2 illustrates the major steps of the process and signals the underlying key anchors and expected learning outcomes.

Stage 1, which involved the preliminary definition of a project concept and the search for a colleague/HEI available to participate, was initiated in September 2021 by the teacher at the University of Aveiro, one month prior to the beginning of the semester. When identifying a potential partner, teachers may consider their own network of colleagues or, alternatively, resort to cooperation networks with experience in COIL with the support services of the Rector’s Office at the UA. Due to the impact of the global health crisis on educational activities, the beginning of the academic year at the UA had been considerably delayed; as a result, it proved to be rather difficult to find a partner HEI available to adapt their much earlier initiated classes to this collaboration request. In spite of this, with the extraordinary support of colleagues from other international HEIs it was possible to connect with the UTCC teacher and together work on a solution to promote the intended cross-cultural learning: at UTCC, classes had also begun much earlier and it would not have been feasible to articulate a COIL initiative with classroom assignments already in progress; considering the circumstances, inviting volunteer students to participate was the option that we considered most adequate. Unlike UA students, UTCC students were not subject to any formal evaluation. For UTCC students, this activity assumed the form of extracurricular learning, which allowed them to practice their English-speaking skills and interact/learn with peers from a distant location and with different cultural backgrounds while simultaneously deepening their understanding of themselves and their culture.

During stage 2, a document with the project summary, general and specific goals, advantages for students, interaction strategies, ethical procedures, outputs, and required tasks was produced by the teachers at the two HEIs. Concomitantly, the UTCC teacher called for volunteers interested in becoming “intercultural buddies” of ELBC students. A total of 25 students (18 students from the School of Humanities, 5 from the International School of Management, and 2 from the School of Business) responded positively, with the majority (56%) being 1st-year students and 24% 4th-year students; 3 students were in their 2nd year and 2 students were in their 3rd year. These students were also taking different degrees, most of them studying either English for Business Communication (7) or English for Professional and International Communication (7); the other participants’ degrees included Accountancy (3), Chinese (3), International Business (2), and Korean, as well as Business Administration and International Business Management, with one student each.

After the activity plan was outlined and the list of participants was organized, the activity was officially registered at the Pedagogical Office at the University of Aveiro. It was through this formalization that all participants were granted a certificate that acknowledged the collaboration as a virtual exchange or internationalization experience [

11].

Stage 3, implementation, was set in motion in November, with a Zoom meeting attended by all participating students. In this introductory session, students (as well as two representatives of the UTCC International Office) were formally introduced to the project’s concept, the three main pillars that constituted it (student-centered learning, collaboration, and research work), the tasks that ELBC students were required to complete, the possible discussion topics to be explored during the following weeks (

Figure 1), and the different deadlines. ELBC students were required to submit their research papers by 17 December, right before the Christmas break; the oral presentations were scheduled for 28 January, shortly after the return to in-person classes, following a contention period declared by the Government to control a possible post-holiday surge in COVID-19 cases.

The relevance and expected learning outcomes of the project were also explained to students, as well as the added value of their involvement in a process that would encourage them to (i) research and think critically about relevant intercultural communication topics; (ii) work collaboratively with peers from different cultural backgrounds and learn from the internal insights these could bring into their conversations; (iii) build new relationships and develop people skills, such as empathy and tolerance; (iv) become active participants in their own learning, especially in the case of ELBC students; and (v) develop academic writing skills, design skills and creativity, as well as oral presentation skills. Before concluding this initial session, the 10 interinstitutional teams (previously organized by the teachers) were invited to join breakout rooms and allowed time to meet each other, exchange contacts, and schedule their next encounters.

During stage 4, execution, the groups conducted research, met online to collect complementary data (at their own pace), and worked on their papers and oral presentations. During these two months, the ELBC teacher ran weekly check-ins and provided guidance and support whenever requested; doubts related to citing and referencing or advice on approaches to tackling certain topics (especially topics students perceived as sensitive) were the most common issues.

As initially defined, UA students submitted their short papers in December and presented their work on the last day of the term, in January 2022, before their peers and teachers. It is worth highlighting that some groups produced quite interesting, high-quality assignments, despite this being a new and challenging experience for them as undergraduates. Students’ grades were published shortly after, and stage 5 was concluded with the activity assessment and the attribution of participation certificates.

2.4. Students’ Perceptions

After the end of the semester, ELBC students were invited by their teacher to answer an online questionnaire (designed using the Google Forms tool), which was anonymous and non-mandatory. It included multiple-choice, checkbox, and open questions to assess the self-perceived development of a set of specific skills, as well as the overall learning experience. After running a small-scale preliminary test to ascertain the feasibility of the questionnaire, data from 16 students were collected (76.2% response rate).

The first part of the questionnaire was divided into two sections. A Likert-like scale from 1 to 5 was used in Section 1.1, which aimed to gauge students’ perceptions of how the activity had contributed to the development of specific competencies—(i) cognitive skills, (ii) social and emotional skills, and (iii) digital skills—which were loosely grouped according to the

OECD Learning Compass 2030 [

5] framework. (The

OECD Learning Compass 2030 framework [

5] distinguishes between three different types of skills: (i) cognitive and meta-cognitive skills, which include critical thinking, creative thinking, learning-to-learn, and self-regulation, while cognitive skills enable the use of language, numbers, reasoning, and acquired knowledge, the latter including learning-to-learn skills and the ability to recognize one’s knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values; (ii) social and emotional skills, which include empathy, responsibility, and collaboration. These are projected in an individual’s patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors which enable personal development and the cultivation of relationships in different interaction contexts, as well as the exercise of an individual’s civic responsibilities; and (iii) practical and physical skills, which include functional skills for using new information and communication technology devices.) Section 1.2 inquired about the most used collaborative tools and digital resources.

Analysis of the data showed that, on average, the students considered the accomplishment of the activity as being positive, especially regarding the development of social and emotional skills. With relatively low dispersion, empathy and respect for others (4.56), responsibility (4.44), intercultural awareness and sensitivity (4.25), and communication and collaboration (4.13) received the highest scores (

Table 1). In terms of cognitive/metacognitive skill development (

Table 2), the combined data showed that the development of specific terminology (4.40) and research/information selection skills (4.40) were the most valued items. Digital skills received a combined score of 4.25. With a score of 3.90, critical thinking and problem solving were considered the less developed competencies.

Additionally, to determine the consistency of scores within this dataset, the first (Q1) and third quartiles (Q3) were calculated. As illustrated in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, 75% of students assessed every item with 4 points or above. In terms of social and emotional skills, every item scored 5.0, except for autonomy and organization and time management, which scored 4.8 and 4.0, respectively. Regarding cognitive/functional skills, 75% of students assessed the development of specific terminology, research and information selection skills, and digital skills with 5.0; whereas research and information selection skills and critical thinking and problem solving scored 4.8, English communication skills and creativity scored 4.0. Critical thinking and problem solving, which received a mean score of 3.9 and was therefore considered the less developed competence, received a score of 3.0 from only 25% of students (Q1), which means that for the majority of the group this activity contributed significantly to the development of this particular competence as well.

In Section 1.2, students were asked about the chosen technological tools and resources. In answer to the question “Which collaborative tools did you use more often to communicate with your group?”, Zoom (62.5%), WhatsApp (56.3%), Instagram (56.3%), Facebook Messenger (53.6%), and Google Docs (43.8%) were by far the most selected options. Despite their popularity in other countries, none of the groups used Google Meet, Microsoft Teams, Webex, or Discord for their online interactions. Regarding the question “Which platforms, digital tools and other technological resources did you use for the accomplishment of your assignment (research + paper writing + presentation materials)?”, 93.8% of the students relied heavily on generalist Google as a source of information and knowledge, and 50% indicated having consulted Google Scholar, while 6.3% indicated that they had used ResearchGate. Regarding their oral presentation design, PowerPoint (81.37%); free image websites, such as Pixabay, Unsplash, and Pexels (37.5%); and the graphic design platform Canva (31.3%) were the most used resources. On the whole, the resources and collaboration and communication technologies used in the project helped students acquire/further develop important skills (virtual teamwork, project management, business communication, intercultural competence, etc.) and therefore strengthen competencies for the global digital workplace.

After this component of a more reflective nature with guided questions that helped students think critically about their performance and interactions, in the second part of the questionnaire, which aimed at assessing the overall learning experience, students were invited to comment on their experience. To provide some guidance, the open-ended questions indicated in

Table 3 were posed. The overall feedback was positive, generally in line with the selection of responses below. Students acknowledged the importance of bringing such virtual, global learning activities into the classroom, not only because these are “challenging”, “interesting”, and “motivating”, but also because such initiatives represent an opportunity to contact cultures they would not otherwise have the chance to. This experience allowed students to identify the commonalities and differences between the participants, as well as recognize personal limitations in dealing with/accepting different worldviews, attitudes and beliefs, patterns of behavior, etc. Ultimately, this collaboration helped students to be more open-minded about cultural differences, develop strategies to tackle topics that may be perceived as sensitive, and, overall, gain awareness of the importance of intercultural communication learning.