Excursions as an Immersion Pedagogy to Enhance Self-Directed Learning in Pre-Service Teacher Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

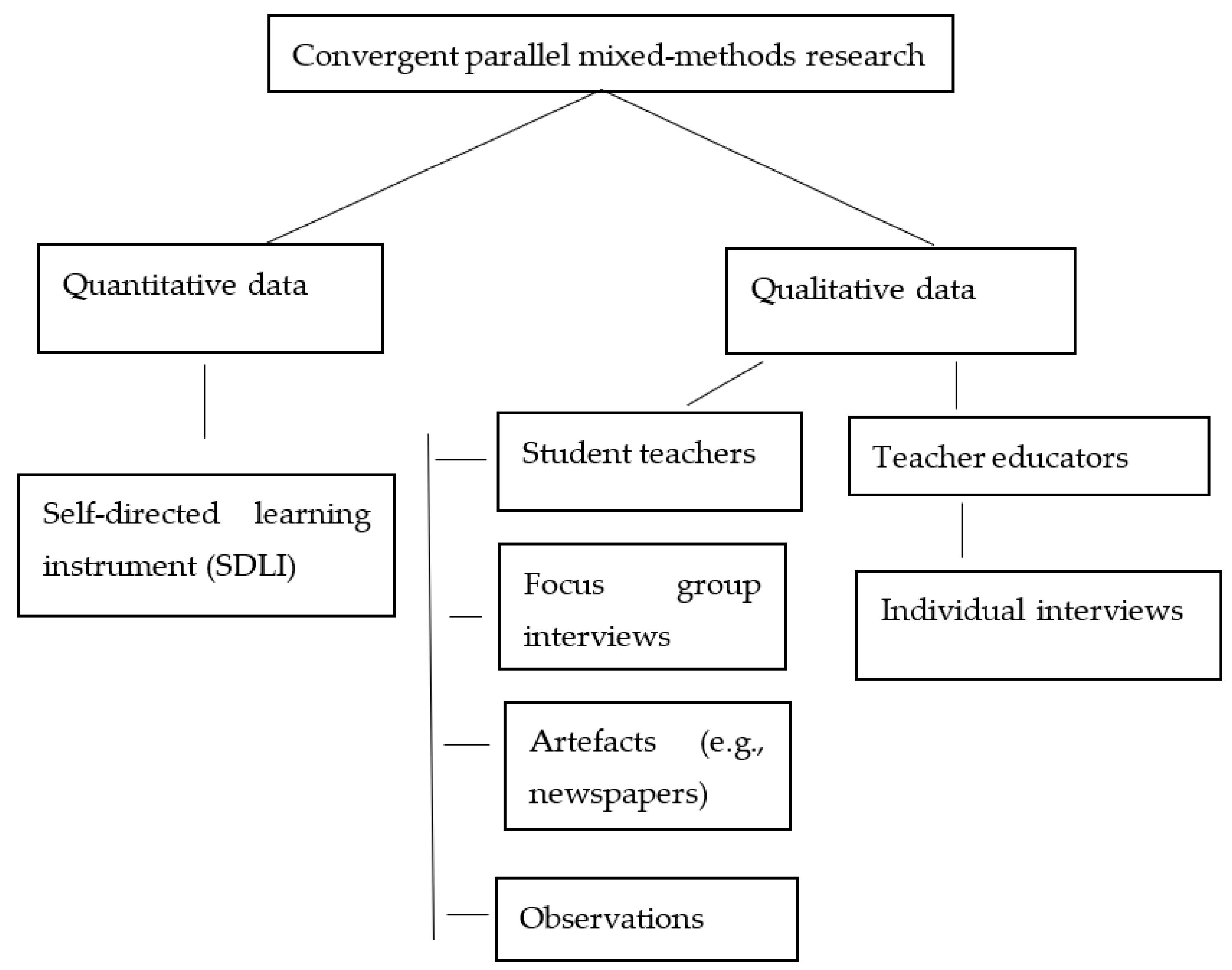

2.1. Research Paradigm and Design

2.2. Research Population and Sampling

2.3. Research Instruments and Data Analysis

2.4. Validity and Reliability

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results and Findings

3.1. Excursions as a Vehicle to Sensitize Student Teachers towards the Importance of Environmental Education in the Age of Environmental Emergencies

3.2. Designing Excursion Programmes on Sound Theoretical Frameworks and Teaching and Learning Philosophies

3.2.1. The Excursion Developed Sensitivity to Cultural Diversity

3.2.2. The Excursion Exposed Student Teachers to Different Semiotic Tools for Teaching and Learning

3.2.3. The Excursion Sensitised Students to Self-Directed Learning

3.2.4. The Excursion Sensitised Students to the Importance of Reflection

3.3. Excursions Hold Affordances in Pre-Service Teacher Education in Both Face-to-Face and Online (Virtual) Learning Environments

3.4. Addressing the Affective Domain, and Specific Student Needs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Petersen, N.; Mentz, E.; De Beer, J. First-year students’ conceptions of the complexity of the profession, sense of belonging, and self-directed learning. In Self-Directed Learning in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Research on the Affordances of Online Virtual Excursions; De Beer, J., Petersen, N., Van Vuuren, H.J., Eds.; AOSIS: Cape Town, South Africa, 2020; pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lortie, D. Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Rusznyak, L. Learning to explain: How student teachers organize and present content knowledge in lessons they teach. J. Curric. Stud. 2011, 15, S95–S109. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/16823206.2011.643632 (accessed on 15 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, A. The Predictive Value of Pre-Entry Attributes for Student Academic Performance in the South African Context. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto, V. The Principles of Effective Retention. Fall Conference of the Maryland College Personnel Association, 20 November 1987. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED301267.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2012).

- Taljaard, S. The Value of an Excursion in the Professional Development of Preservice Teacher Education Students. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- De Beer, J.; Petersen, N.; Dunbar-Krige, H. An exploration of the value of an educational excursion for pre-service teachers. J. Curric. Stud. 2012, 44, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke Da Silva, K. Biological fieldwork in Australian higher education: Is it worth the effort? Int. J. Innov. Sci. Math. Educ. 2014, 22, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, N.; De Beer, J.; Mentz, E. The first-year student teacher as a self-directed learner. In Becoming a Teacher: Research on the Work-Integrated Learning of Student Teachers; De Beer, J., Petersen, N., Van Vuuren, H.J., Eds.; AOSIS: Cape Town, South Africa, 2020; pp. 115–155. [Google Scholar]

- Sebotsa, T.; Petersen, N.; Speight Vaughn, M. The role of work-integrated learning excursions in preparing student teachers for diverse classrooms and teaching social justice in South African classrooms. In Becoming a Teacher: Research on the Work-Integrated Learning of Student Teachers; De Beer, J., Petersen, N., Van Vuuren, H., Eds.; AOSIS: Cape Town, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Beer, J.; Petersen, N.; Conley, L. Withitness in the virtual learning space: Reflections of student-teachers and teacher-educators. In Self-Directed Learning in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Research on the Affordances of Online Virtual Excursions; De Beer, J., Petersen, N., Mentz, E., Balfour, R., Eds.; AOSIS: Cape Town, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga, J. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfi, H.E. Teaching in the age of environmental emergencies: A utopian exploration of the experiences of teachers committed to environmental education in England. Educ. Rev. 2023, 75, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research design. In Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systemic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 5th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.-F.; Kuo, C.-L.; Lin, K.-C.; Hsieh, J. Development and preliminary testing of a self-rating instrument to measure self-directed learning ability of nursing students. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 1152–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 4th ed.; Bossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop, L.; Rushton, E.A. Putting climate change at the heart of education: Is England’s strategy a placebo for policy? Br. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 46, 1083–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, N.; Osman, R. The teacher as a caring professional. In Becoming a Teacher, 2nd ed.; Gravett, S., De Beer, J., Du Plessis, E., Eds.; Pearson: Cape Town, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H. Living Dangerously: Multiculturalism and the Politics of Difference; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings, N. Caring: A Feminist Approach to Ethics and Moral Education; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, M. Self-Directed Learning: A Guide for Learners and Teachers; Prentice Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Brookfield, S. The Power of Critical Theory: Liberatory Adult Learning and Teaching; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- De Beer, J.; Henning, E. Retreating to a Vygotskian stage where pre-service teachers play out social ‘dramatical collisions’. Acta Acad. 2011, 43, 203–228. [Google Scholar]

- Veresov, N. Zone of proximal development: The hidden dimension? In Sprak Som Kultur (Language as Culture); Ostern, A., Heila-Ostern, R., Eds.; Vasa Publishers: Richmond, Canada, 2004; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280322665_Veresov_N_2004_Zone_of_Proximal_Development_ZPD_the_Hidden_Dimension_In_Ostern_A_Heila-Ylikallio_R_Eds_Sprak_som_kultur_-_brytningar_I_tidoch_rum_-_Language_as_culture_-_tensions_in_time_and_space_Vol (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Vygotsky, L. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.; Johnson, R. An Overview of Cooperative Learning. 1994. Available online: http://digsys.upc.es/ed/general/Gasteiz/docs-_ac/Johnson_Overview_of_Cooperative_Learning.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2016).

- Kounin, J. Discipline and Group Management in Classrooms; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Fiock, H. Designing a community of inquiry in online courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2020, 21, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.T.; Hutchings, P. Integrative Learning: Mapping the Terrain; Association of American Colleges and Universities: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; Available online: https://researchgate.net/publication/254325229 (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Kessels, P.; Korthagen, F. The relationship between theory and practice: Back to the classics. Educ. Res. 1996, 25, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L. Powerful Teacher Education: Lessons from Exemplary Programs; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smagorinsky, P.; Cook, L.S.; Johnson, T.S. The twisting path of concept development in learning to teach. In Proceedings of the Fifth Congress of the International Society of Cultural Research and Activity Theory, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 18–22 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Mean (Pre) | Mean (Post) | STD (Pre) | STD (Post) | p-Value | Cohen d-Value | Hedges Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LM | 4.43 | 4.75 | 0.54 | 0.32 | <0.001 | 0.53 | 0.54 |

| PI | 4.13 | 4.37 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.001 | 0.61 | 0.62 |

| SM | 4.16 | 4.43 | 0.63 | 0.60 | <0.001 | 0.62 | 0.62 |

| IC | 4.14 | 4.46 | 0.72 | 0.52 | <0.001 | 0.73 | 0.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Beer, J. Excursions as an Immersion Pedagogy to Enhance Self-Directed Learning in Pre-Service Teacher Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090862

De Beer J. Excursions as an Immersion Pedagogy to Enhance Self-Directed Learning in Pre-Service Teacher Education. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(9):862. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090862

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Beer, Josef. 2023. "Excursions as an Immersion Pedagogy to Enhance Self-Directed Learning in Pre-Service Teacher Education" Education Sciences 13, no. 9: 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090862

APA StyleDe Beer, J. (2023). Excursions as an Immersion Pedagogy to Enhance Self-Directed Learning in Pre-Service Teacher Education. Education Sciences, 13(9), 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090862