Assessing the Enactus Global Sustainability Initiative’s Alignment with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Lessons for Higher Education Institutions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Contextualization of Terms

1.1.1. Sustainability Practices

1.1.2. Sustainable Development Goals

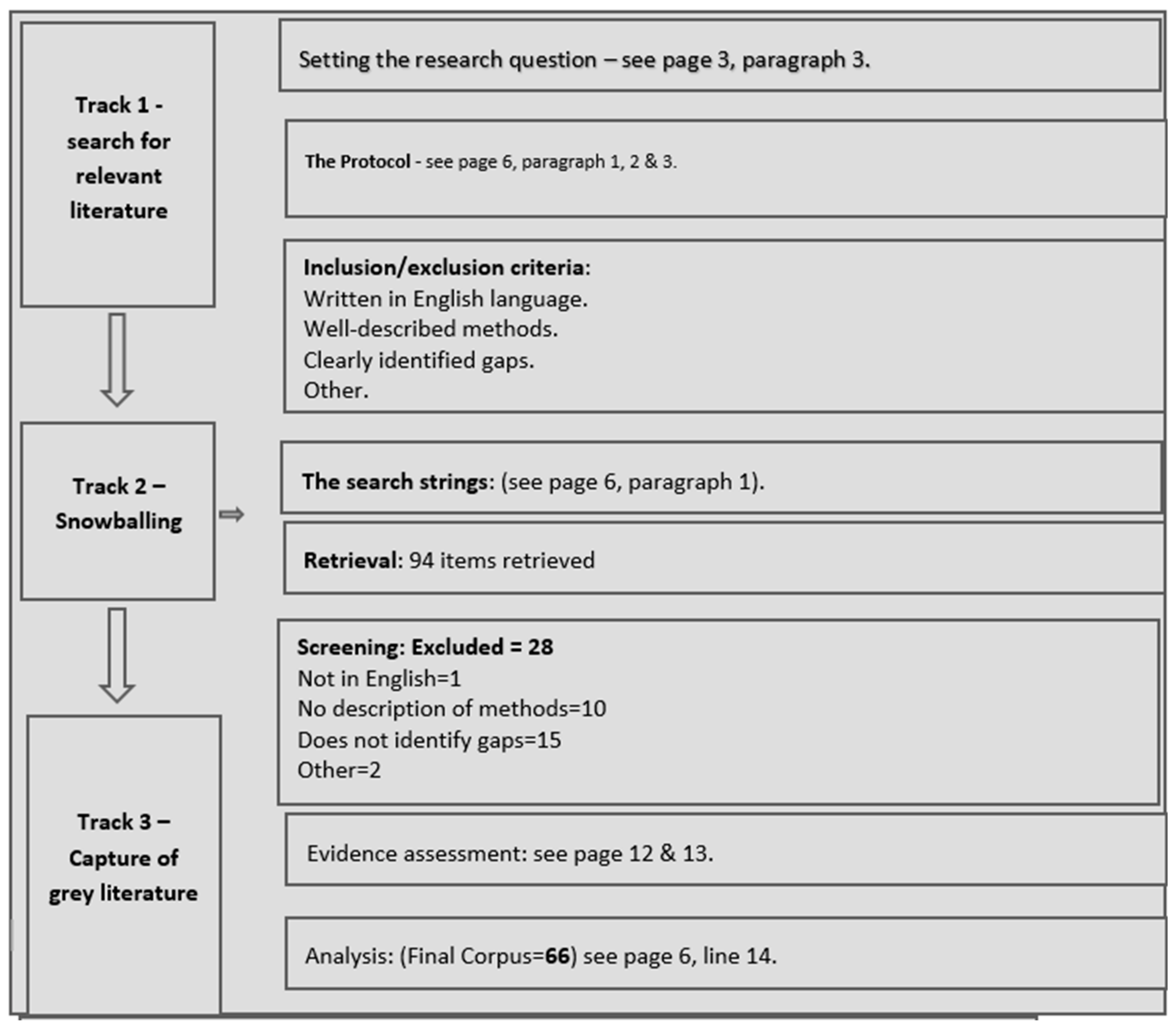

2. Conceptual Approach, Method of Data Collection and Materials

- Only peer-reviewed English-language papers were included in the list of chosen articles.

- Web of Science and Scopus were the main databases used to find relevant articles (Core Collection); however, more materials were obtained from other unconventional sources to strengthen the data required for the analysis.

- The following search strings were utilized: ‘Youth’ OR ‘University Student’ OR ‘University-based Entrepreneurial Projects’ OR ‘Community Development Initiative’ OR ‘Sustainability Initiative’ OR ‘Student-led Enactus Teams’ OR ‘Student-led Enactus Projects’ OR ‘Social Entrepreneurship Projects’ OR Sustainability Strategies’ OR ‘Sustainability Practices’ AND ‘2030 Global Goals’ OR ‘SDGs’ OR ‘Sustainable Development Goals’ OR Community Development’ OR ‘Nation Building’ OR ‘Sustainable Development’. The search was restricted to the abstract, keywords and title.

- Each abstract was examined for relevance, and only articles that were strictly related to the topic were selected.

- After the confirmation that each article was closely related to the research topic, it was downloaded and thoroughly examined. Moreover, 94 research papers were identified in the initial search; however, after exclusion criteria were applied, 66 papers emerged as the final corpus since they were strictly relevant to the study.

3. Triple Bottom Line Theory

4. Findings

4.1. Relationship between Enactus Sustainability Initiative and the UN Sustainable Development Goals

| Category | Project | Host Institution | Significance | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education & Skills Training | EMSSA Project | University of South Africa | This project aims to enhance the comprehension of individuals residing in marginalized communities regarding the economic and environmental challenges they encounter. It also seeks to provide specific solutions to ameliorate these situations. Additionally, the initiative focuses on tackling the economic obstacles that underprivileged communities confront, while simultaneously fostering the leadership abilities of Enactus student team members. | [50] |

| Business Hive | Central University of Technology | The objective of this project is to equip small- and medium-sized enterprises with essential operational resources, enabling their connection to potential funders. This endeavor encourages students to engage with industry experts, fostering the acquisition of abilities like marketing and financial management. In this context, Enactus students partner with business professionals to strengthen the capabilities of small business proprietors, particularly aspiring young entrepreneurs. The overarching goal is to facilitate the growth of their enterprises, thereby generating increased employment opportunities. | [51] | |

| After21 | University of KwaZulu-Natal | The main focus of this initiative is to assist individuals with disabilities. This project aims to empower them by fostering their abilities to create and sell handmade products, thus enabling them to contribute to their families’ income. This endeavor aligns with the United Nations’ principle of inclusivity, ensuring that no one is excluded. Enactus students involved in this project not only learn about the true nature of social entrepreneurship but also play a crucial role in enhancing the economic independence of people with disabilities within their communities. | [52] | |

| Kutanga | University of the Free State | This project provides students from less privileged backgrounds in high school and higher education with the opportunity to explore entrepreneurship. Within this initiative, students gain valuable skills through practical learning experiences, including hands-on activities, deriving lessons from setbacks, and drawing insights from successful entrepreneurs. The project holds the promise of amplifying the students’ productive capabilities in both high school and higher education settings. | [53] | |

| Fresh moves | North-West University | The objective of this project is twofold: to boost the recognition of local brands and create an environment that encourages connections among student entrepreneurs. This undertaking aims to equip student entrepreneurs with teamwork abilities through an apprenticeship model. The project nurtures cooperation, networking, and collaborative aptitude among students. Ultimately, the project’s main goal is to enhance the long-term economic viability of the community. | [51] | |

| Recycle Projects | Fuel In Plastic Waste | University of Fort Hare | This student-driven project by Enactus centers on the conversion of plastic into fuel using pyrolysis. By engaging in this endeavor, students acquire practical expertise in pyrolysis technology along with valuable project management abilities. Furthermore, the project not only tackles environmental issues but also motivates young individuals to become catalysts for positive change within their respective communities. | [51] |

| Phoenix | University of Pretoria | Project Phoenix utilizes fly ash in an innovative manner to produce bricks. By reducing the usage of expensive aggregates like cement and crusher sand, the cost of the bricks is lowered. This not only enables students to gain insights into sustainable construction techniques but also promotes environmental sustainability by reducing the amount of waste sent to landfills. Additionally, it addresses issues associated with traditional brick manufacturing methods. | [51] | |

| Project EcoFinance | University of KwaZulu-Natal | The EcoFinance Project generates income for individuals through recycling endeavors. This recycling project addresses both economic and ecological concerns by providing students with income opportunities while also mitigating pollution problems within communities. | [52] | |

| Tala Loha | North-West University | Tala Loha Enactus student project, which centers on converting plastic waste into sellable hats and bags. The primary goals are twofold: creating revenue streams and tackling the environmental concerns linked to plastic pollution. This endeavor not only seeks to reduce the negative ecological effects of plastic waste but also provides students with a chance to earn money and acquire valuable vocational skills. | [50] | |

| Lego-Brick Housing Project | University of the Western Cape | Enactus students engage in projects involving the utilization of repurposed plastic bottles from which they construct cost-effective housing using Lego bricks. This practical involvement empowers students to devise innovative strategies for addressing housing challenges within various communities. Through this hands-on encounter, students acquire tangible skills and foster a mindset for social entrepreneurship. | [53] | |

| Digital Innovations | Amanzi Social Enterprise | University of KwaZulu-Natal | In this endeavor, Enactus students utilize a contemporary digital system equipped with advanced sensors to assess water quality. This initiative addresses the challenges of water scarcity in South Africa, enabling students to develop proficiencies in technology and hands-on abilities while simultaneously addressing urgent social concerns. | [52] |

| Red Light Project | University of the Free State | This digital initiative offers users the information required to uphold their physiological well-being, along with the capacity to recognize potential medical issues and proactively respond. It enables students to acquire expertise in managing their own health, facilitating informed choices and overall welfare. Furthermore, the project equips individuals to monitor their health advancements and potentially establish personal health objectives. | [52] | |

| Umdlalo Virtual Gaming Centre | University of Johannesburg | By imparting coding skills and creating indigenous African games, this project brings fresh innovation to the gaming field within South Africa. It enables students to showcase their inventive talents while also nurturing a sense of cultural variety within the gaming sector. Furthermore, it bridges the gap that exists between education and technology. | [53] | |

| Noteworthy | University of Cape Town | Noteworthy Project aims to blend digital technology with education in order to enhance academic success by simplifying the learning experience in rural areas. It enables students to cultivate digital competencies, potentially leading to the creation of educational resources and learning prospects that were previously inaccessible. This endeavor strives to narrow the socioeconomic disparity between affluent and underprivileged individuals in rural communities. | [51] | |

| MzansiKonnect | Central University of Technology | The MzansiKonnect project utilizes digital resources to bridge the gap between rural and urban businesses. Furthermore, it links small and medium-sized enterprises with prospective customers. It also enables students to enhance their digital competencies. The project serves a dual function by fostering the growth of rural communities and driving the digital evolution of SMEs in rural regions. | [51] | |

| Agro-allied Projects | Sack space | University of KwaZulu-Natal | Sack space is a low-cost and simple-to-maintain type of vertical farming enterprise. This technique comprises planting a variety of veggies in a bag. In contrast to conventional farming practices, this experience could develop student capacity for innovation and creativity in agriculture. | [52] |

| Ubuntu Social Enterprise | University of KwaZulu-Natal | Ubuntu is an agribusiness project that provides free skills-based training to small-scale peasant farmers. This provides a chance for agricultural workers to acquire knowledge about eco-friendly farming methods and innovative ways of running a flexible farming business. Furthermore, the initiative acts as a support system for farmers, enabling them to make valuable contributions to addressing food security concerns within their local communities. | [50] | |

| Vukezenzele | University of Zululand | Vukezenzele functions as a collaborative endeavor where students learn about agricultural methods to ensure food security and foster employment opportunities. This exposure familiarizes students with sustainable practices in farming and emphasizes the significance of large-scale economic operations. The cooperative not only refines teamwork abilities but also imparts essential entrepreneurial skills vital for running prosperous agricultural ventures. | [50] | |

| Green life | University of Venda | This idea revolves around agriculture, where Enactus students work together with local communities to cultivate and market fresh crops to neighboring villages. This hands-on involvement aids students in developing entrepreneurial abilities while also encouraging local production and availability of healthy foods. Additionally, it contributes to the economic prosperity of farmers by establishing viable and lasting livelihood opportunities. | [51] | |

| Ukutya Kwemvelo | University of Fort Hare | This agricultural endeavor is located in the chicken farm locality of Mdantsane in the Eastern Cape. Its primary aim is to address the significant levels of unemployment and poverty. Through this initiative, Enactus students acquire practical knowledge about the fundamentals of raising chickens. By offering a means of sustenance to the local inhabitants, the project effectively addresses the poverty challenges in the area. | [52] |

4.2. Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of Enactus Student-Led Projects

5. Discussion of Findings

6. Practical Implications

7. Key Lessons for Universities Aiming to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals

7.1. HEIs Have a Crucial Task in Achieving the SDGs, as Education Is Linked to Almost All of the SDGs

7.2. South African Higher Education Institutions Need to Urgently Address Knowledge Gaps among Their Stakeholders Regarding the Implementation of SDGs

7.3. Knowledge Sharing Is Crucial to Achieving the SDGs

7.4. Motivating University Stakeholders to Adopt a Flexible Approach towards SDG Implementation Is Crucial Due to the Prevailing Resistance to Change among Faculty Members

7.5. Adopting Multidisciplinary and Multi-Stakeholder Approaches to Achieve the SDGs Can Assist HEIs in Building Partnerships

7.6. Localization of SDGs in Every Higher Education Institution in South Africa Is Imperative

7.7. Raising Sustainability Awareness across Universities

8. Concluding Remarks

9. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carlsen, L.; Bruggemann, R. The 17 United Nations’ sustainable development goals: A status by 2020. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2022, 29, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, J. Entrepreneurial skills to be successful in the global and digital world: Proposal for a frame of reference for entrepreneurial education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 356. [Google Scholar]

- Mahlatsi, K. Achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) In Africa: Challenges and Prospects. Think 2021, 87, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawonde, A.; Togo, M. Implementation of SDGs at the university of South Africa. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 932–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geza, W.; Ngidi, M.S.C.; Slotow, R.; Mabhaudhi, T. The dynamics of youth employment and empowerment in agriculture and rural development in South Africa: A scoping review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimanzi, M.K. The role of higher education institutions in fostering innovation and sustainable entrepreneurship: A case of University in South Africa. 2020. Available online: http://ir.cut.ac.za/handle/11462/2411 (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Dalibozhko, A.; Krakovetskaya, I. Youth entrepreneurial projects for the sustainable development of global community: Evidence from Enactus program. SHS Web Conf. 2018, 57, 01009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolyanchuk, K.B. Beneficial Participation in ENACTUS (Ph.D. Dissertation, VNTU). 2017. Available online: http://ir.lib.vntu.edu.ua/bitstream/handle/123456789/17707/2236.pdf?sequence=3 (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Tshishonga, N.S. Addressing the unemployed graduate challenge through student entrepreneurship and innovation in South Africa’s higher education. In Cases on Survival and Sustainability Strategies of Social Entrepreneurs; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 161–181. [Google Scholar]

- Nhamo, G. Localisation of SDGs in Higher Education: Unisa’s whole institution, all goals and entire sector approach. South. Afr. J. Environ. Educ. 2021, 37, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimah, P.; Appiah, K.O.; Appiagyei, K. Seven years of United Nations’ sustainable development goals in Africa: A bibliometric and systematic methodological review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 395, 136422. [Google Scholar]

- Mingst, K.A.; Karns, M.P.; Lyon, A.J. The United Nations in the 21st Century; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2022; Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=MtdjEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=united+nations+2022&ots=mvgXCyOW3Z&sig=uCSaXz0Quq3QRSQxaKanjDI1tMo (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Henderson, K.; Loreau, M. A model of Sustainable Development Goals: Challenges and opportunities in promoting human well-being and environmental sustainability. Ecol. Model. 2023, 475, 110164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshikovhi, N. The Effect of Practical Entrepreneurship Education in South Africa. Student Entrepreneurship Promotion through Enactus Entrepreneurial Projects; GRIN Verlag: München, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://www.amazon.com/practical-entrepreneurship-education-promotion-Entrepreneurial/dp/3346153460 (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Vezi-Magigaba, M.F. Developing Women Entrepreneurs: The Influence of Enactus Networks on Women-Owned SMMEs in Kwa Zulu-Natal. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Zululand, Richards Bay, South Africa, 2018. Available online: https://uzspace.unizulu.ac.za/handle/10530/1721 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Kapoor, S.; Singh, H.; Ray, A.; Mattoo, T.; Manwal, S.; Katoch, A.; Kapoor, E.; Gupta, G. Enactus SSBUICET. In Frontline Workers and Women as Warriors in the COVID-19 Pandemic; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2022; p. 3. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=7viBEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT136&dq=project+uday+enactus+ssbuicet+team+of+panjab+university+india&ots=XuMcLT94GR&sig=jTULyWI5I4wfcONxi_NxE82uCFI (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Weik, S.M. Developing the Next Generation of Socially Responsible Employees: The Case of Enactus at Oregon State University. 2014. Available online: https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/downloads/kd17cv84k (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Raji, A.; Hassan, A. Sustainability and stakeholder awareness: A case study of a Scottish university. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, D.R.; Shrestha, P. Knowledge management initiatives for achieving sustainable development goal 4.7: Higher education institutions’ stakeholder perspectives. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 1109–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.K.; Mishra, I. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, 2030 and environmental sustainability: Race against time. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 2, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, K.; Nhamo, G. Sustainable development goals localisation in the tourism sector: Lessons from Grootbos private nature reserve, South Africa. GeoJournal 2021, 86, 2191–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnason, S.; Li, C.J.; Hall, D.M.; Wilhelm Stanis, S.A.; Schulz, J.H. Environmental action programs using positive youth development may increase civic engagement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, P.J.; Sosa, S.; Velez-Calle, A. Business for peace: How entrepreneuring contributes to Sustainable Development Goal 16. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2023, 26, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, L.K.; Funke, N.; Audouin, M.; Musvoto, C.; Nahman, A. The Sustainable Development Goals in South Africa: Investigating the need for multi-stakeholder partnerships. Dev. S. Afr. 2019, 36, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Bae, J.H.; Rishi, M. Sustainable development and SDG-7 in Sub-Saharan Africa: Balancing energy access, economic growth, and carbon emissions. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2023, 35, 112–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoki, O. Sustainability orientation and sustainable entrepreneurial intentions of university students in South Africa. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 7, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhong, F.; Song, X.; Huang, C. Exploring the impact of poverty on the sustainable development goals: Inhibiting synergies and magnifying trade-offs. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, C.; Warchold, A.; Pradhan, P. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Are we successful in turning trade-offs into synergies? Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.; Farnan, J.M.; Grafton-Clarke, C.; Ahmed, R.; Gurbutt, D.J.; Daniel, M.M. Non-technical skills assessments in undergraduate medical education: A focused BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 54. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen-Zanker, J.; Mallett, R. How to Do a Rigorous, Evidence-Focused Literature Review in International Development: A Guidance Note. Available online: https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/8572.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Farooq, Q.; Fu, P.; Liu, X.; Hao, Y. Basics of macro to microlevel corporate social responsibility and advancement in triple bottom line theory. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; Frost, G.; Webber, W. Triple bottom line: A review of the literature. In The Triple Bottom Line; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013; pp. 39–47. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781849773348-2/triple-bottom-line-review-literature-carol-adams-geoff-frost-wendy-webber (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Elkington, J. The triple bottom line. Environ. Manag. Read. Cases 1997, 2, 49–66. Available online: https://www.johnelkington.com/archive/TBL-elkington-chapter.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- Żak, A. Triple bottom line concept in theory and practice. Soc. Responsib. Organ. Dir. Changes 2015, 387, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, J. and Pivo, G. The triple bottom line and sustainable economic development theory and practice. Econ. Dev. Q. 2017, 31, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasella, B.; Wylie, A.; Gill, D. The role of higher education institutions (HEIs) in educating future leaders with social impact contributing to the sustainable development goals. Soc. Enterp. J. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimperna, F.; Nappo, F.; Marsigalia, B. Student entrepreneurship in universities: The state-of-the-art. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malunga, P.; Iwu, C.G.; Mugobo, V.V. Social entrepreneurs and community development. A literature analysis. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Dey, A.; Singh, G. Connecting corporations and communities: Towards a theory of social inclusive open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2017, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshilo, A.; Lethoko, M. The contribution of youth in Local Economic Development and entrepreneurship in Polokwane municipality, Limpopo Province. Ski. Work: Theory Pract. J. 2017, 8, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mawonde, A.; Togo, M. Challenges of involving students in campus SDGs-related practices in an ODeL context: The case of the University of South Africa (Unisa). Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 1487–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netshilinganedza, T.R. Factors Influencing the Attitudes of Final Year Undergraduate Students towards Entrepreneurship as a Career Option: A Case-Study at the University of Venda in Limpopo Province of South Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa, 2020. Available online: https://univendspace.univen.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11602/1540/Thesis%20-%20Netshilinganedza%2C%20t.%20r.-.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- Ynestrillas Vega, A.G.; Kallab, E.; Gandhi, S.; Eke-Okocha, N.P.; Sawaya, J. A Comparative Analysis of the Role of the Youth in Localizing SDG 11 at the Local Level in the Global North and Global South. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022, 15, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, N.; Antil, A.; Gunasekaran, A.; Malik, K.; Balakumar, S. Environment-social-governance disclosures nexus between financial performance: A sustainable value chain approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manigandan, P.; Alam, M.S.; Alagirisamy, K.; Pachiyappan, D.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H. Realizing the Sustainable Development Goals through technological innovation: Juxtaposing the economic and environmental effects of financial development and energy use. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 8239–8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorós Adams Molina, Á.; Helldén, D.; Alfvén, T.; Niemi, M.; Leander, K.; Nordenstedt, H.; Rehn, C.; Ndejjo, R.; Wanyenze, R.; Biermann, O. Integrating the United Nations sustainable development goals into higher education globally: A scoping review. Glob. Health Action 2023, 16, 2190649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, B.; Muurlink, O.; Best, T. Social entrepreneurship education: Global experiential learning and innovations in Enactus. In Annals of Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 308–313. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone, G.; Ughetto, E.; Landoni, P. Entrepreneurial intention: An analysis of the role of student-led entrepreneurial organizations. J. Int. Entrep. 2021, 19, 399–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazana, S.; McLaren, L.; Kabungaidze, T. Transforming while transferring: An exploratory study of how transferability of skills is key in the transformation of higher education. Transform. High. Educ. 2018, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkoana, E.M.; Dichaba, M.M. ‘Them and Us’: Exploring the Socio-Political Sustainability of South African Universities in an Era of ‘Dangerous’ stakeholders. In Rethinking Education in the 21st Century; African Academic Research Forum: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017; Volume 3, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- De Jager, H.J.; Mthembu, T.Z.; Ngowi, A.B.; Chipunza, C. Towards an innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystem: A case study of the central university of technology, free state. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2017, 22, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P. Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=MZmQBAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=james+2014+sustainability&ots=wtCoo7dBgs&sig=JfETyjGJILKFJe_1yJP2dK_lGUc (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Taylor, S.; Spowart, J. Creating future-fit leaders: Towards formalising service learning in university programmes. In EDULEARN14 Proceedings; IATED: Valencia, Spain, 2014; pp. 1813–1819. [Google Scholar]

- Fofana, I.; Chitiga-Mabugu, M.; Mabugu, R. South Africa Milestones to Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals on Poverty and Hunger; The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Volume 1731, Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=MrVoDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT16&dq=South+Africa+Milestones+to+Achieving+the+Sustainable+Development+Goals+on+Poverty+and+Hunger&ots=HkcL7y9M9x&sig=cLJeDP7uYg-GaflA_qMfxszQL1s (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Rampasso, I.S.; Siqueira, R.G.; Martins, V.W.; Anholon, R.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Leal Filho, W.; Lange Salvia, A.; Santa-Eulalia, L.A. Implementing social projects with undergraduate students: An analysis of essential characteristics. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Filho, J.M.D.; Granados, M.L.; Lacerda Fernandes, J.A. Social entrepreneurial intention: Educating, experiencing and believing. Stud. High. Educ. 2023, 48, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittaway, L.A.; Gazzard, J.; Shore, A.; Williamson, T. Student clubs: Experiences in entrepreneurial learning. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2015, 27, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, C.; Delport, H.; Perold, R.; Weber, A.M.; Brown, J.B. Being-in-context through live projects: Including situated knowledge in community engagement projects. Crit. Stud. Teach. Learn. 2021, 9, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshikovhi, N.; Shambare, R. Entrepreneurial knowledge, personal attitudes, and entrepreneurship intentions among South African Enactus students. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2015, 13, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Lettmann, S.; Schmoeckel, P. From Global Problem to Local Solution—How a Fiture Directed Circular Economy Can Foster Social Change. In Social and Cultural Aspects of circular Economy. Towards Solodarity and Inclusivity; Pal, V., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK.

- Maruyama, S.; Kurokawa, A. The operation of school lunches in Japan: Construction of a system considering sustainability. Jpn. J. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 76, S12–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, J.; Johari, H.S.Y.; Bakri, A.A.; Razak, W.M.W.A. Students and Women Entrepreneurs’ Collaborations in Social Entreprise Program at UiTM, Malaysia. Proc.-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 168, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, P. Dublin’s and Ireland’s Entrepreneurial Revolution: The Force Awakens. In Entrepreneurial Renaissance: Cities Striving towards an Era of Rebirth and Revival; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 127–141. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-52660-7_8 (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- El Ghaib, M.K.; Chaker, F. Partnership for high social impact in Africa: A conceptual and practical framework. In Management and Leadership for a Sustainable Africa, Volume 2: Roles, Responsibilities, and Prospects; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 191–214. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, T.; Wuttunee, W. Our hearts on our street: Neechi Commons and the social enterprise centre in Winnipeg. Univ. Forum 2015, 4, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Iljadica, A.; Feeney, M.; Seymour, R.; Stewart, N.; Martinez, C.; Ormiston, J.; Nguyen, L. Entrepreneurship and Innovation Program Annual Report 2014. 2015. Available online: https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/13904 (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Zeng, Y.; Maxwell, S.; Runting, R.K.; Venter, O.; Watson, J.E.; Carrasco, L.R. Environmental destruction not avoided with the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 795–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, M.; Rathgeber, A.; Fulton, L.; Schmutz, B. Sustainability & CSR: The Relationship with Hofstede Cultural Dimensions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12052. [Google Scholar]

- Reverte, C. The importance of institutional differences among countries in SDGs achievement: A cross-country empirical study. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 1882–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimirova, K.; Le Blanc, D. Exploring links between education and sustainable development goals through the lens of UN flagship reports. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edokpayi, J.N.; Rogawski, E.T.; Kahler, D.M.; Hill, C.L.; Reynolds, C.; Nyathi, E.; Smith, J.A.; Odiyo, J.O.; Samie, A.; Bessong, P.; et al. Challenges to sustainable safe drinking water: A case study of water quality and use across seasons in rural communities in Limpopo province, South Africa. Water 2018, 10, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohde, R.A.; Muller, R.A. Air pollution in China: Mapping of concentrations and sources. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135749. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/partnerships/ (accessed on 11 March 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.M.J.; Che-Ha, N.; Alwi, S.F.S. Service customer orientation and social sustainability: The case of small medium enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, V.; Maré, A. Implementing the National Development Plan? Lessons from coordinating grand economic policies in South Africa. Politikon 2015, 42, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbanda, V.; Fourie, W. The 2030 Agenda and coherent national development policy: In dialogue with South African policymakers on Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Costa, L.; Rybski, D.; Lucht, W.; Kropp, J.P. A systematic study of sustainable development goal (SDG) interactions. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfour, R.J.; Mitchell, C.; Moletsane, R. Troubling contexts: Toward a generative theory of rurality as education research. J. Rural Community Dev. 2008, 3, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Govindan, K.; Xie, X. How fairness perceptions, embeddedness, and knowledge sharing drive green innovation in sustainable supply chains: An equity theory and network perspective to achieve sustainable development goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 120950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestin, T.; van den Belt, M.; Denby, L.; Ross, K.; Thwaites, J.; Hawkes, M. Getting Started with the SDGs in Universities: A Guide for Universities, Higher Education Institutions, and the Academic Sector. 2017. Available online: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017-08/apo-nid105606.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- World Vision International and The Partnering Initiative. Delivering on the Promise. In Country Multi-Stakeholder Platforms to Catalyse Collaboration and Partnerships for Agenda 2030. Agenda 2030 Implementation Policy Brief. 2016. Available online: http://wvi.org/sites/default/files/Delivering%20on%20the%20promise%20-%20in%20country%20multi-stakeholder%20platforms%20for%20Agenda%202030.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Omotosho, A.O.; Akintolu, M.; Kimweli, K.M.; Modise, M.A. Assessing the Enactus Global Sustainability Initiative’s Alignment with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Lessons for Higher Education Institutions. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 935. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090935

Omotosho AO, Akintolu M, Kimweli KM, Modise MA. Assessing the Enactus Global Sustainability Initiative’s Alignment with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Lessons for Higher Education Institutions. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(9):935. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090935

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmotosho, Ademola Olumuyiwa, Morakinyo Akintolu, Kimanzi Mathew Kimweli, and Motalenyane Alfred Modise. 2023. "Assessing the Enactus Global Sustainability Initiative’s Alignment with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Lessons for Higher Education Institutions" Education Sciences 13, no. 9: 935. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090935

APA StyleOmotosho, A. O., Akintolu, M., Kimweli, K. M., & Modise, M. A. (2023). Assessing the Enactus Global Sustainability Initiative’s Alignment with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Lessons for Higher Education Institutions. Education Sciences, 13(9), 935. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090935