A Whole Education Approach to Inclusive Education: An Integrated Model to Guide Planning, Policy, and Provision

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Educational Policy Movement towards Inclusive Provision

1.2. Inclusion as a Place

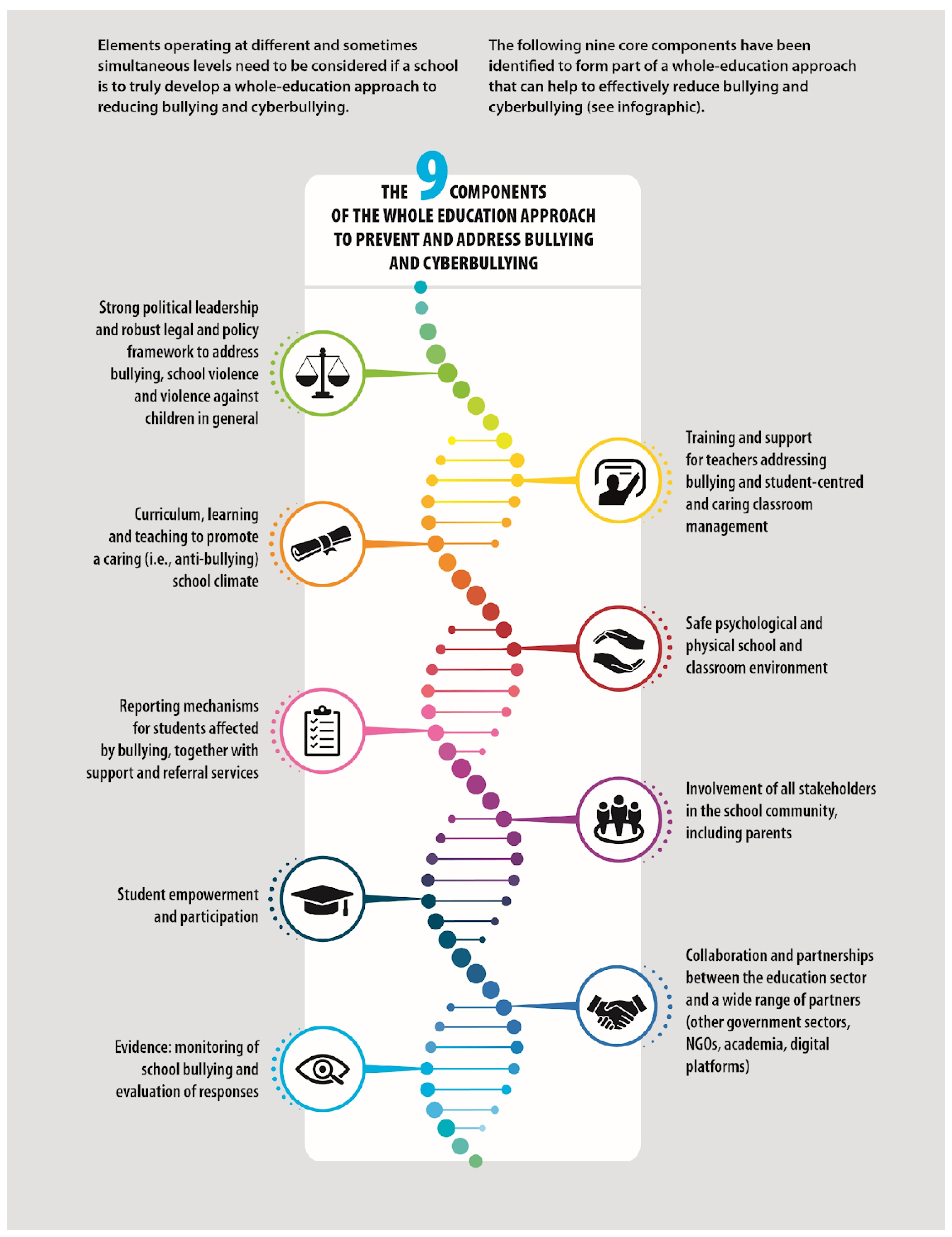

2. A Whole Education Approach to Inclusion

2.1. Strong Political Leadership

2.2. Safe Psychological and Physical School and Classroom Environments

2.3. Training and Support for School Staff

2.4. Curriculum, Learning, and Teaching to Promote a Caring School Climate

2.5. Reporting Mechanisms with Support and Referral Services

2.6. Collaboration and Partnerships between the Education Sector and a Wide Range of Partners

2.7. Involvement of All Stakeholders in the School Community, Including Parents

2.8. Student Empowerment and Participation

2.9. Monitoring of Bullying and Evidence of Successful Responding

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Assembly. Convention on the Rights of the Child; United Nations, Treaty Series; United Nations Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 1989; Volume 1577. [Google Scholar]

- Cornu, C.; Abduvahobov, P.; Laoufi, R.; Liu, Y.; Séguy, S. An Introduction to a Whole-Education Approach to School Bullying: Recommendations from UNESCO Scientific Committee on School Violence and Bullying Including Cyberbullying. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Higgins Norman, J.; Berger, C.; Yoneyama, S.; Cross, D. School Bullying: Moving beyond a Single School Response to a Whole Education Approach. Pastor. Care Educ. 2022, 40, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoninis, M.; April, D.; Barakat, B.; Bella, N.; D’Addio, A.C.; Eck, M.; Endrizzi, F.; Joshi, P.; Kubacka, K.; McWilliam, A.; et al. All Means All: An Introduction to the 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report on Inclusion. Prospects 2020, 49, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olweus, D. Bully/Victim Problems in School: Facts and Intervention. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 1997, 12, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. School Bullying: Development and Some Important Challenges. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 751–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, C.; Pascoe, C.J. A Sociology of Bullying: Placing Youth Aggression in Social Context. Sociol. Compass 2023, 17, e13071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, H.; Ttofi, M.M.; Farrington, D.P. Evaluating the Effectiveness of School-Bullying Prevention Programs: An Updated Meta-Analytical Review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 45, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, C.-J.; Kim, D.H. A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of School-Based Anti-Bullying Programs. J. Child Health Care 2015, 19, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Cyberbullying: Neither an Epidemic nor a Rarity. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 9, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Florian, L. What Counts as Evidence of Inclusive Education? Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2014, 29, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M.; Banks, J. Inclusion at a Crossroads: Dismantling Ireland’s System of Special Education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education: Adopted by the World Conference on Special Needs Education; Access and Quality. Salamanca, Spain, 7–10 June 1994; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Leijen, Ä.; Arcidiacono, F.; Baucal, A. The Dilemma of Inclusive Education: Inclusion for Some or Inclusion for All. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 633066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelis, P.; Pedaste, M. A Model of Inclusive Education in the Context of Estonian Preschool Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Eest. Haridusteaduste Ajak. Est. J. Educ. 2020, 8, 138–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Resolution/adopted by the General Assembly, 24 January 2007, A/RES/61/106. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/45f973632.html (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Kenny, N.; McCoy, S.; Mihut, G. Special Education Reforms in Ireland: Changing Systems, Changing Schools. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, S.J.; Banks, D.; Frawley, D.; Watson, D.; Shevlin, M. Understanding Special Class Provision in Ireland: Findings from a National Survey of Schools; ESRI and National Council for Special Education: Dublin, Ireland, 2014; Available online: https://www.esri.ie/publications/understanding-special-class-provision-in-ireland-findings-from-a-national-survey-of (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Ainscow, M. Taking an Inclusive Turn. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2007, 7, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihut, G.; McCoy, S.; Maître, B. A Capability Approach to Understanding Academic and Socio-Emotional Outcomes of Students with Special Educational Needs in Ireland. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2022, 48, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL—Google Search. 1962. Available online: https://www.lri.fr/~mbl/Stanford/CS477/papers/Kuhn-SSR-2ndEd.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- McCombs, B.L. Integrating Metacognition, Affect, and Motivation in Improving Teacher Education. In How Students Learn: Reforming Schools through Learner-Centered Education; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 379–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.F.N.; Alkin, M.C. Academic and Social Attainments of Children with Mental Retardation in General Education and Special Education Settings. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2000, 21, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M.; Miles, S. Making Education for All Inclusive: Where Next? Prospects 2008, 38, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornby, G. Inclusive Special Education: Development of a New Theory for the Education of Children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2015, 42, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, M.; Pearpoint, J. Families, Friends, and Circles. In Natural Supports in School, at Work, and in the Community for People with Severe Disabilities; Paul H. Brookes: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1992; pp. 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C.; Dyson, A.; Millward, A. Towards Inclusive Schools? Routledge: London, UK, 2018; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Ainscow, M.; Booth, T.; Dyson, A. Improving Schools, Developing Inclusion; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.J.; Slee, R. An Illusory Interiority: Interrogating the Discourse/s of Inclusion. Educ. Philos. Theory 2008, 40, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, J. Inclusive Schooling: If It’s so Good—Why Is It so Hard to Sell? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2015, 19, 530–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauchlan, F.; Greig, S. Educational Inclusion in England: Origins, Perspectives and Current Directions. Support Learn. 2015, 30, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramidis, E.; Norwich, B. Teachers’ Attitudes towards Integration / Inclusion: A Review of the Literature. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2002, 17, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education Inspectorate. Educational Provision for Learners with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Special Classes Attached to Mainstream Schools in Ireland; Department of Education and Skills Inspectorate: Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.; McCoy, S. An Irish Solution…? Questioning the Expansion of Special Classes in an Era of Inclusive Education. Econ. Soc. Rev. 2017, 48, 441–461. [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Special Education. Inclusive Education Framework: A Guide for Schools on the Inclusion of Pupils with Special Educational Needs; National Council for Special Education: Trim, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bangkok, U. Embracing Diversity: Toolkit for Creating Inclusive, Learning-Friendly Environments; UNESCO: Bangkok, Thailand, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ainscow, M. The SAGE Handbook of Special Education; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2007; pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffers, G. Attitudes to Transition Year: A report to the Department of Education and Science. Available online: https://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/1228/ (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Barnes-Holmes, Y.; Scanlon, G.; Desmond, D.; Shevlin, M.; Vahey, N. A Study of Transition from Primary to Post-Primary School for Pupils with Special Educational Needs; National Council for Special Education Research Report No. 12; National Council for Special Education: Trim, Ireland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Special Education. Policy Advice on Special Schools and Classes: An Inclusive Education for an Inclusive Society? National Council for Special Education: Trim, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini, A.; Menesini, E.; Salmivalli, C. Level and Change of Bullying Behavior during High School: A Multilevel Growth Curve Analysis. J. Adolesc. 2013, 36, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, M.; Korn, S.; Brodbeck, F.C.; Wolke, D.; Schulz, H. Bullying Roles in Changing Contexts: The Stability of Victim and Bully Roles from Primary to Secondary School. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2005, 29, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zych, I.; Ttofi, M.M.; Llorent, V.J.; Farrington, D.P.; Ribeaud, D.; Eisner, M.P. A Longitudinal Study on Stability and Transitions Among Bullying Roles. Child Dev. 2020, 91, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation); French Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports. International Conference on School Bullying: Recommendations by the Scientific Committee on Preventing and Addressing School Bullying and Cyberbullying. 2020. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374794 (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Purdy, N. School Policies, Leadership, and School Climate. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Bullying; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, C.; Kenny, N. “A Different World”—Supporting Self-Efficacy among Teachers Working in Special Classes for Autistic Pupils in Irish Primary Schools. REACH J. Incl. Educ. Irel. 2022, 35, 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage, D.L.; Forber-Pratt, A.; Rose, C.A.; Graves, K.A.; Hanebutt, R.A.; Sheikh, A.E.; Woolweaver, A.; Milarsky, T.K.; Ingram, K.M.; Robinson, L.; et al. Development of Online Professional Development for Teachers: Understanding, Recognizing and Responding to Bullying for Students with Disabilities. Educ. Urban Soc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Bauman, S. Teachers: A Critical But Overlooked Component of Bullying Prevention and Intervention. Theory Into Pract. 2014, 53, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, S.; Collins, B. Bullying Prevention Through Curriculum and Classroom Resources. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Bullying; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 278–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Mulhall, P.F.; Flowers, N.; Lee, N.Y. Bullying Reporting Concerns as a Mediator Between School Climate and Bullying Victimization/Aggression. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP11531–NP11554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, J.; Radford, J. The SENCO Role in Post-Primary Schools in Ireland: Victims or Agents of Change? Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2017, 32, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, S.; Sharma, U.; Furlonger, B. The Inclusive Practices of Classroom Teachers: A Scoping Review and Thematic Analysis. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 25, 735–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, L.; Spratt, J. Enacting Inclusion: A Framework for Interrogating Inclusive Practice. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2013, 28, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnes, E.; Done, E.J.; Knowler, H. Mainstream Teachers’ Concerns about Inclusive Education for Children with Special Educational Needs and Disability in England under Pre-Pandemic Conditions. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2022, 22, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, S.; Holton, S.; Baxter, R.; Burgoyne, K. Educational Experiences of Pupils with Down Syndrome in the UK. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 119, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras, I.; Amor, A.M.; Verdugo, M.Á.; Calvo, M.I. Operationalisation of Quality of Life for Students with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities to Improve Their Inclusion. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 119, 104093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisbu-Sakarya, Y.; Doenyas, C. Can School Teachers’ Willingness to Teach ASD-Inclusion Classes Be Increased via Special Education Training? Uncovering Mediating Mechanisms. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 113, 103941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreman, T.; Forlin, C.; Sharma, U. Measuring Indicators of Inclusive Education: A Systematic Review of the Literature. In Measuring Inclusive Education; International Perspectives on Inclusive Education; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; Volume 3, pp. 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M. Promoting Inclusion and Equity in Education: Lessons from International Experiences. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2020, 6, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Ireland. Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act 2004; Government of Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education. Autism Good Practice Guidance for Schools—Supporting Children and Young People; 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/8d539-autism-good-practice-guidance-for-schools-supporting-children-and-young-people/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Berlach, R.G.; Chambers, D.J. Interpreting Inclusivity: An Endeavour of Great Proportions. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2011, 15, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, L. ‘Voice’ Is Not Enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 33, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreman, T.J.; Deppeler, J.M.; Harvey, D.H. Inclusive Education—Supporting Diversity in the Classroom, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Messiou, K. Understanding Marginalisation through Dialogue: A Strategy for Promoting the Inclusion of All Students in Schools. Educ. Rev. 2019, 71, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, N.; Doyle, A.; Horgan, F. Transformative Inclusion: Differentiating Qualitative Research Methods to Support Participation for Individuals With Complex Communication or Cognitive Profiles. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, J. Special Class Provision in Ireland: Where We Have Come from and Where We Might Go. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kenny, N.; McCoy, S.; O’Higgins Norman, J. A Whole Education Approach to Inclusive Education: An Integrated Model to Guide Planning, Policy, and Provision. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090959

Kenny N, McCoy S, O’Higgins Norman J. A Whole Education Approach to Inclusive Education: An Integrated Model to Guide Planning, Policy, and Provision. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(9):959. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090959

Chicago/Turabian StyleKenny, Neil, Selina McCoy, and James O’Higgins Norman. 2023. "A Whole Education Approach to Inclusive Education: An Integrated Model to Guide Planning, Policy, and Provision" Education Sciences 13, no. 9: 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090959

APA StyleKenny, N., McCoy, S., & O’Higgins Norman, J. (2023). A Whole Education Approach to Inclusive Education: An Integrated Model to Guide Planning, Policy, and Provision. Education Sciences, 13(9), 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090959