Photographs of Play: Narratives of Teaching

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Outcome 1: Children have a strong sense of identity;

- Outcome 2: Children are connected with and contribute to their world;

- Outcome 3: Children have a strong sense of wellbeing;

- Outcome 4: Children are confident and involved learners;

- Outcome 5: Children are effective communicators.

- Allows for the expression of personality and uniqueness;

- Offers opportunities for multimodal play;

- Enhances thinking skills and lifelong learning dispositions such as curiosity, persistence and creativity;

- Enables children to make connections between prior experiences and new learning and to transfer learning from one experience to another;

- Assists children to develop and build relationships and friendships;

- Develops knowledge acquisition and concepts in authentic contexts;

- Builds a sense of identity;

- Strengthens self-regulation, and physical and mental wellbeing.

- What can we learn about play and the teaching of young children across two generations in Australia through the implementation of visual narrative inquiry?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Global Perspectives on Play in Education

2.2. Importance of Play in Early Childhood: A Worldwide View

2.3. Australian Perspectives on Play in Education and Early Childhood

2.4. Definition of Play in the Education and Early Childhood Context

2.5. Play-Based Learning in Australia

2.6. The Australian Early Years Learning Framework (EYLF) and Play

2.7. Noteworthy Australian Studies and Authors

3. Family and School Photographs

4. Methodology

Visual Analysis

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. Family 1

| 1980s | Late 2010s | |

| Playing with puzzles and construction sets |  |  |

| Outside climbing activities |  |  |

| Portraits |  |  |

5.2. Family 2

| 1980s | 2020s | |

| Engaging with collage—using a range of different materials |  |  |

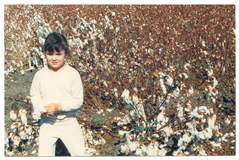

| Outside activities exploring how things grow |  |  |

| Portraits |  |  |

5.3. Family 3

| 1980s | 2020s | |

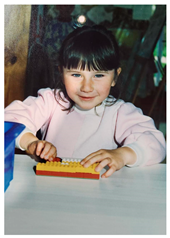

| Fine-motor development |  |  |

| Portraits |  |  |

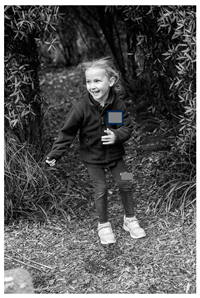

| Gross-motor development |  |  |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR). Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia; Commonwealth of Australia: Barton, Australia, 2009.

- Australian Government Department of Education [AGDE]. Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia (V2.0); Australian Government Department of Education for the Ministerial Council: Canberra, Australia, 2022.

- Siraj-Blatchford, I.; Muttock, S.; Sylva, K.; Gilden, R.; Bell, D. Researching Effective Pedagogy in the Early Years; University of London, Institute of Education, Department of Educational Studies: Norwich, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton-Smith, B. The Ambiguity of Play; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, A.; Parker, R.; Thomsen, B.S. Learning Through Play at School: A Framework for Policy and Practice. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 751801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCarlo, S. Importance of Play in Early Childhood [Blog Post]. 2012. Available online: https://importanceofplayinearlychildhood.wordpress.com/literature-review/ (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Griswold, K. Play in Early Childhood; Northwestern College: Orange City, Iowa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, C. Childhood, Play, and School: A Literature Review in Australia; Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mielonen, A.M.; Paterson, W. Developing Literacy through Play. J. Inq. Action Educ. 2009, 3, 15–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pyle, A.; Danniels, E. A Continuum of Play-Based Learning: The Role of the Teacher in Play-Based Pedagogy and the Fear of Hijacking Play. Early Educ. Dev. 2017, 28, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA]. Australian Curriculum (v9.0). 2022. Available online: https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Duncan, R.M.; Tarulli, D. Play as the leading activity of the preschool period: Insights from Vygotsky, Leont’EV, and Bakhtin. Early Educ. Dev. 2003, 14, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, B. Objectives and Perspectives in Education: Studies in Educational Theory 1955–1970; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2013; Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203707050/objectives-perspectives-education-ben-morris (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Cutter-Mackenzie, A.; Edwards, S. Toward a model for early childhood environmental education: Foregrounding, developing, and connecting knowledge through play-based learning. J. Environ. Educ. 2013, 44, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj-Blatchford, I. Conceptualising progression in the pedagogy of play and sustained shared thinking in early childhood education: A vygotskian perspective. Educ. Child Psychol. 2009, 26, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleer, M. Early Learning and Development Cultural-Historical Concepts in Play; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, M. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, G. Doing Family Photography; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P.; Boltanski, L.; Castel, R.; Chamboredun, J.-C.; Schnapper, D. Photography: A Middle-Brow Art; Whiteside, S., Translator; Cambridge Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, M.; Spitzer, L. School Photos in Liquid Time: Reframing Difference; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, J.; Holland, P. Family Snaps: The Meanings of Domestic Photography; Virago: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, A. Family Secrets: Acts of Memory and Imagination; Verso: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, N.M. Drawing and Writing: Journeys, Transitions and Milestones In Understanding and Supporting Young Writers’ from Birth to 8; Mackenzie, N.M., Scull, J., Eds.; Abingdon Oxon Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Preschool Education, Australia Methodology. 2020. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/methodologies/preschool-education-methodology/2020 (accessed on 29 July 2023).

- Barthes, R. Camera Lucida; Hill and Wang: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Pyle, A.; DeLuca, C.; Danniels, E. A scoping review of research on play-based pedagogies in Kindergarten Education. Rev. Educ. 2017, 5, 311–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Decade | Play Theory/Pedagogical Focus |

|---|---|

| 1970–1980 | Focus on Arts and Craft Play with connections to developing Mathematical Thinking [13] |

| 1980–1990 | A Vygotskian Influence of Social Cultural Play—learning occurs through social interaction and through engagement with the world, rules, expectations and observation of social roles [12] |

| 1990–2000 | Focus on structured play environments [10,16] |

| 2000–2010 | Focus on Conceptual Play—imaginary play, based on multimodal literacies [17] |

| 2010–2020 | Focus is on the relationships between educators and students and how educators “play a role” in the students lives [14,15] |

| Family | Mother | Attended ECE | Child | Attended ECE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ange | 1980s | Louis | 2010s |

| 2 | Susie (Author 1) | 1980s | Emilie | 2020s |

| 3 | Natalie (Author 3) | 1980s | Noah | 2020s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garvis, S.; Keary, A.; McCallum, N. Photographs of Play: Narratives of Teaching. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010100

Garvis S, Keary A, McCallum N. Photographs of Play: Narratives of Teaching. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(1):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010100

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarvis, Susanne, Anne Keary, and Natalie McCallum. 2024. "Photographs of Play: Narratives of Teaching" Education Sciences 14, no. 1: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010100