A Typology of Multiple School Leadership

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Technological Leadership

- What structures, methods, procedures and techniques can be used to achieve the planned goals and targets of a school?

- How can aims and related tasks be achieved more effectively through changes in the structure, methodology or technology of a school? Why?

- Can any technical innovations and improvements be made or the process of school functioning be reengineered to ensure sustainable development and effectiveness?

3. Economic Leadership

- What resources and costs are needed and what benefits can be generated in the action cycle of a school or its members?

- How can the planned aims of a school be achieved with minimal cost or resources in the action process?

- In what way can the marginal benefits be innovatively maximized from the action process of a school in general and its members in particular?

4. Social Leadership

- Who are the major stakeholders and actors involved in school action and what are the social relationships among them?

- How can relationships with these members affect the aims, processes and outcomes of the school and its development?

- How can human needs be satisfied and synergy be maximized among involved members to pursue school effectiveness and development? Why?

5. Political Leadership

- What diversities, interests and powers of school actors and other stakeholders are involved in leadership efforts for achieving school effectiveness and development?

- How can the conflicts and struggles in a school be minimized or managed to sustain school development and stability through alliance building, partnership, negotiation, democratic process and other strategies or tactics? Why?

- How can “win-win” strategies be built to overcome political obstacles, facilitate school action and maximize the achievement of school aims in the long run?

6. Cultural Leadership

7. Learning Leadership

- What kinds of learning styles, thinking modes and conceptual knowledge can be used in the practice of learning leadership for pursuing multiple learning functions and sustaining school development?

- How can the aims and nature of school action be re-conceptualized to be more adaptive to changes and challenges in the context?

- How can learning gaps be minimized and how can new thinking modes and new understanding about multiple learning functions be achieved?

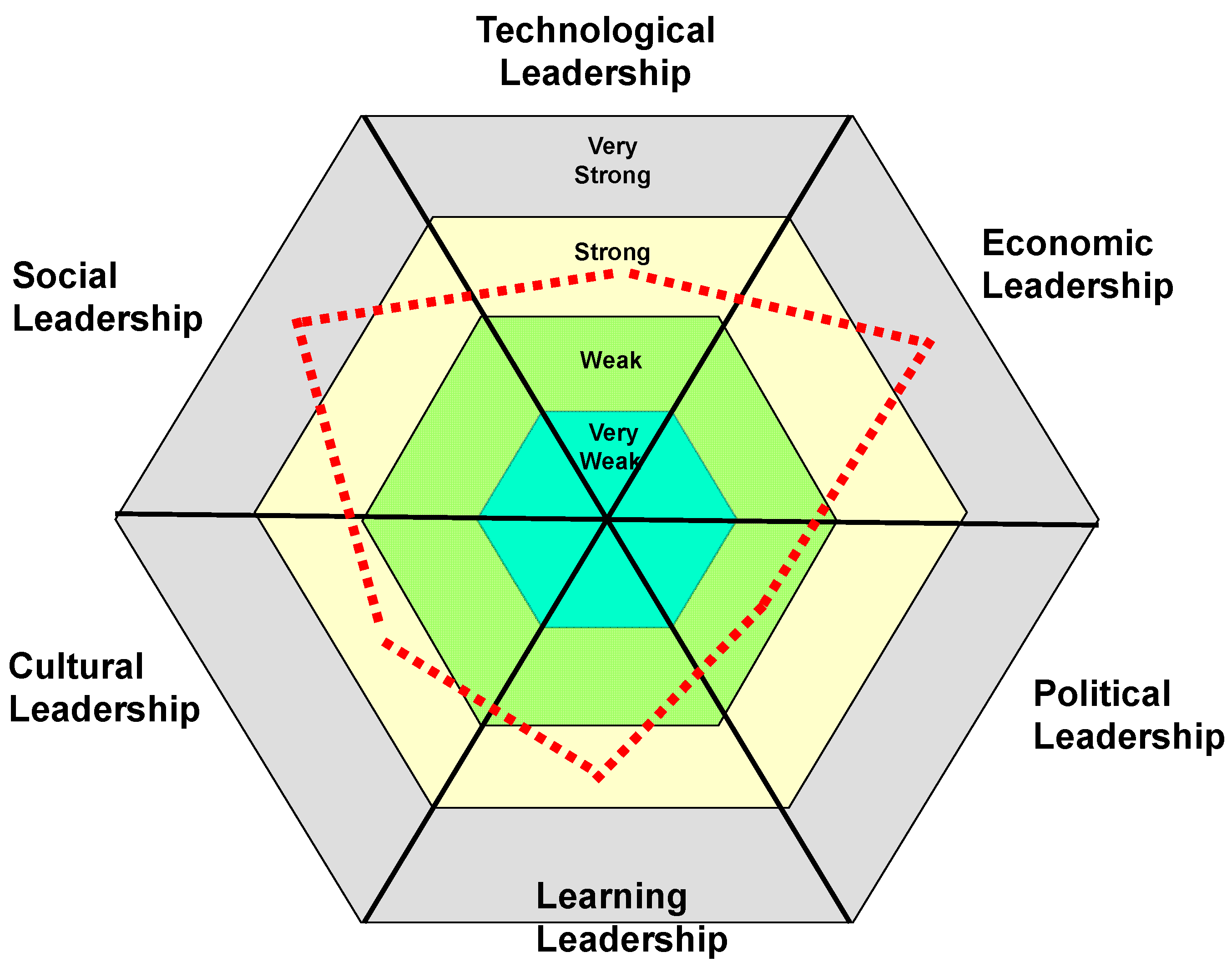

8. Profiles of Multiple Leadership

9. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leithwood, K.; Harris, A.; Hopkins, D. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 40, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. COVID-19–school leadership in crisis? J. Prof. Cap. Community 2020, 5, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.C. The futures of education in globalization: Multiple drivers. In The Third International Handbook of Globalization, Education and Policy Research; Zajda, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Chapter 2; pp. 15–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.Y.; Gao, L.; Shi, M. Second-order meta-analysis synthesizing the evidence on associations between school leadership and different school outcomes. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2022, 50, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Sun, J.; Schumacker, R. How school leadership influences student learning: A test of “The four paths model”. Educ. Adm. Q. 2020, 56, 570–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Sammons, P.; Gorgen, K. Successful School Leadership; Education Development Trust; ERIC: Berkshire, UK, 2020.

- Bush, T.; Glover, D. School leadership models: What do we know? Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2014, 34, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gougas, V.; Malinova, L. School Leadership. Models and Tools: A Review. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 9, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolman, L.G.; Deal, T.E. Reframing Organizations: Artistry, Choice and Leadership; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.C. New Paradigm for Re-Engineering Education: Globalization, Localization and Individualization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Section 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M. Transformational leadership in education: A review of existing literature. Int. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2017, 93, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Teodoro, A. Contesting the Global Development of Sustainable and Inclusive Education: Education Reform and the Challenges of Neoliberal Globalization; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Litz, D. Globalization and the changing face of educational leadership: Current trends and emerging dilemmas. Int. Educ. Stud. 2011, 4, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pont, B. A literature review of school leadership policy reforms. Eur. J. Educ. 2020, 55, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.C. School Effectiveness and School-Based Management: A Mechanism for Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.C. Paradigm Shift in Education: Towards the 3rd Wave of Effectiveness; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bernacki, M.L.; Greene, J.A.; Crompton, H. Mobile technology, learning, and achievement: Advances in understanding and measuring the role of mobile technology in education. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 60, 101827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardhienata, S.; Suchyadi, Y.; Wulandari, D. Strengthening Technological Literacy In Junior High School Teachers In The Industrial Revolution Era 4.0. J. Humanit. Soc. Stud. 2021, 5, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigmatov, Z.G.; Nugumanova, I.N. Methods for Developing Technological Thinking Skills in the Pupils of Profession-oriented Schools. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckart, D.W.; Rogers, J.D. Dewey, Technological Thinking and the Social Studies: The Intelligent use of Digital Tools and Artifacts. Eur. Sci. J. 2017, 13, 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, M.; Reynolds, N. Current and future research issues for ICT in education. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2013, 29, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, V.; Berardi, U.; Dangelico, R.M. Smart cities: Definitions, dimensions, performance, and initiatives. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 22, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.; Bedenlier, S. Facilitating student engagement through educational technology: Towards a conceptual framework. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2019, 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, F.W. The Principles of Scientific Management; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Villers, R. Dynamic Management in Industry; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. The Theory of Social and Economic Organization; Henderson, A.M., Parsons, T., Eds. and Translators; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzhals, C.; Graf-Vlachy, L.; König, A. Strategic leadership and technological innovation: A comprehensive review and research agenda. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2020, 28, 437–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortellazzo, L.; Bruni, E.; Zampieri, R. The role of leadership in a digitalized world: A review. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, C. Economic thinking, traditional ecological knowledge and ethnoeconomics. Curr. Sociol. 2002, 50, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, M.B. (Ed.) Innovations in Economic Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Peña OF, C.; Llanos, R.A.; Coria, M.D.; Pérez-Acosta, A.M. Multidimensional Model of Assessment of Economic Thinking in College Students. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 191, 1623–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, W.W. Consumption and other benefits of education. In Economics of Education: Research and Studies; Psacharopoulos, G., Ed.; Pergamon Press: Kidlington, UK; Oxford, UK, 1987; pp. 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Hinchliffe, K. Education and the labor market. In Economics of Education: Research and Studies; Psacharopoulos, G., Ed.; Pergamon Press: Kidlington, UK; Oxford, UK, 1987; pp. 315–323. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, H.M. Cost-benefit Analysis. In The International Encyclopedia of Education, 2nd ed.; Husén, T., Postlethwaite, T.N., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK; Elsevier Science: New York, NY, USA, 1994; Volume 2, pp. 1127–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Schug, M.C.; Clark, J.R.; Harrison, A.S. Teaching and Measuring the Economic Way of Thinking. In Innovations in Economic Education; Henning, M.B., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Chapter 6; pp. 113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, I. Human Behavior in the Social Environment: A Social Systems Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Greifeneder, R.; Bless, H.; Fiedler, K. Social cognition: How Individuals Construct Social Reality; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, R.; Thayer, A.L.; Shuffler, M.L.; Burke, C.S.; Salas, E. Critical social thinking: A conceptual model and insights for training. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 5, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooke, P. Teaching social skills and social thinking: What matters and why? J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, S49–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.F. Motivation and Personality, 2nd ed.; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- McGregory, D. The Human Side of Enterprise; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Sergiovanni, T. Leadership for the Schoolhouse: How Is It Different? Why Is It Important? 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S. Social networks, social capital, social support and academic success in higher education: A systematic review with a special focus on ‘underrepresented’ students. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 29, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, E.O. Unspoken Politics: Implicit Attitudes and Political Thinking; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J. Managing with Power: Politics and Influence in Organizations; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- DeLue, S.M.; Dale, T.M. Political Thinking, Political Theory, and Civil Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Freeden, M. The Political Theory of Political Thinking. Pol. J. Political Sci. 2015, 1, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, S.; Van Dyne, L. Conceptualization of cultural intelligence: Definition, distinctiveness, and nomological network. In Handbook of Cultural Intelligence; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, S.; Rockstuhl, T.; Tan, M.L. Cultural intelligence and competencies. Int. Encycl. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 2, 433–439. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, M.M.; Takeuchi, R.; Farh, J.L. Enhancing cultural intelligence: The roles of implicit culture beliefs and adjustment. Pers. Psychol. 2017, 70, 257–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. The Corporate Culture; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- White, J.W.; Pascale, A.; Aragon, S. Collegiate cultural capital and integration into the college community. Coll. Stud. Aff. J. 2020, 38, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Pathak, S. Beyond cultural values? Cultural leadership ideals and entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göksoy, S. The Relationship between Principals’ Cultural Intelligence Levels and Their Cultural Leadership Behaviors. Educ. Res. Rev. 2017, 12, 988–995. [Google Scholar]

- Beetham, H.; Sharpe, R. (Eds.) Rethinking Pedagogy for a Digital Age: Designing for 21st Century Learning; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Longworth, N. Lifelong Learning in Action: Transforming Education in the 21st Century; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marsick, V.J.; Bitterman, J.; van der Veen, R. From the Learning Organization to Learning Communities towards a Learning Society; Information Series, No. 382; ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education: Columbus, OI, USA, 2000.

- Boyce, J.; Bowers, A. Toward an evolving conceptualization of instructional leadership as leadership for learning: Meta-narrative review of 109 quantitative studies across 25 years. J. Educ. Adm. 2018, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. Principal instructional leadership: From prescription to theory to practice. Wiley Handb. Teach. Learn. 2018, 505–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBeath, J. Leadership for learning. In Instructional Leadership and Leadership for Learning in Schools; Palgrave Macmillan: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Asbari, M. Is transformational leadership suitable for future organizational needs? Int. J. Soc. Policy Law 2020, 1, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, T.; Bell, L.; Middlewood, D. (Eds.) Principles of Educational Leadership & Management; SAGE Publications Limited: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, M.; James, C.; Fertig, M. The difference between educational management and educational leadership and the importance of educational responsibility. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2019, 47, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J. Leadership and learning: Conceptualizing relations between school administrative practice and instructional practice. In How School Leaders Contribute to Student Success; Leithwood, K., Sun, J., Pollock, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, T.H.; Prusak, L. Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They Know; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Moldoveanu, M.; Narayandas, D. The future of leadership development. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019, 97, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tingle, E.; Corrales, A.; Peters, M.L. Leadership development programs: Investing in school principals. Educ. Stud. 2019, 45, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Andenoro, A.C.; Skendall, K.C. The national leadership education research agenda 2020–2025: Advancing the state of leadership education scholarship. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2020, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. Bringing context out of the shadows of leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 46, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Models of School Leadership | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technological Leadership | Economic Leadership | Social Leadership | Political Leadership | Cultural Leadership | Learning Leadership | |

| Rationalities | Technological Rationality | Economic rationality | Social rationality | Political rationality | Cultural rationality | Adaptive rationality |

| Ideologies | Methodological effectiveness; Goal achievement; Technological engineering; Technical optimization | Efficiency; Cost–benefit; Resources and financial management; Economic optimization | Social relations; Human needs; Social satisfaction | Interest, power and conflict; Participation, negotiation, and democracy | Values, beliefs, ethics and traditions; Integration, coherence and morality | Adaptation to changes; Continuous improvement and development |

| Key concerns in leadership | What structures, methods and technologies can be used? How can the aims be achieved more effectively? Can any technical innovation and improvement be made or the process be reengineered? | What resources and costs are needed and what benefits can be generated? How can the aims be achieved with minimal cost? How is it possible to innovatively maximize the marginal benefits? | Who are the stakeholders involved? How can they affect the aims, processes and outcomes? How can social synergy be maximized? | What diversities, interests and powers are involved? How can the conflicts and struggles be minimized? How can alliances and partnerships be built? | What values, beliefs and ethics are crucial and shared? How do they influence the aims and nature of action? How can integration, coherence or morality in values and beliefs be maximized? | What learning styles, thinking modes and knowledge can be changed? How can school action be more adaptive to the changes and challenges? How can new thinking modes be achieved? |

| Leadership action | To use scientific knowledge and technology to solve problems and achieve school aims | To procure and use resources to implement plans and achieve outcomes | To establish social networks and support to motivate members and implement plans | To negotiate and struggle among parties to manage or solve conflicts | To clarify ambiguities and uncertainties and realize the school vision including key shared values and beliefs | To initiate new ideas and approaches to achieving aims |

| Leadership outcome | A predictable product of good technology and methodology | An output from the calculated use of resources | A product of social networking and relationship building | A result of bargaining, compromise, and interplay among interested parties | A symbolic product of meaning making or culture building | A discovery of new knowledge and approaches to enhancing school functioning |

| Beliefs about planning/development | To find the right technology and methods to overcome difficulties and problems and get things done; To study technological possibilities, strengths and weaknesses | To find out how minimal resources and efforts can be used to produce outcomes; To calculate any economic value added or hidden costs | To find out the optimal social conditions for action and satisfying human needs; To identify any social capital to be accumulated | To find the balance among various political forces for achieving compromise; To search for any possibility for reaching the “win-win” situation and alliance building | To find out cultural meanings behind alternative actions; To derive meanings from possible overt and hidden outcomes | To reflect on the existing modes of thinking and practice and find new modes; To deepen the level of understanding and thinking |

| Context in which that leadership is salient | When the aims of school action are clear and it is very urgent to achieve them | When resources for action are scarce or economic values are strongly emphasized | When school success heavily depends on human and social factors | When the school involves diverse interests and resources are limited to meet expectations | When the school environment is uncertain and the aims and nature of action are not so clear | When the school context is changing fast and adaptation to the changes is crucial |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, Y.-C. A Typology of Multiple School Leadership. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010070

Cheng Y-C. A Typology of Multiple School Leadership. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(1):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010070

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Yin-Cheong. 2024. "A Typology of Multiple School Leadership" Education Sciences 14, no. 1: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010070

APA StyleCheng, Y.-C. (2024). A Typology of Multiple School Leadership. Education Sciences, 14(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010070