A Conceptual Framework Supporting Translanguaging Pedagogies in Secondary Dual-Language Programs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on Translanguaging Pedagogies

2.2. Gap in Research on Secondary Dual Language Programs

2.3. Traditional vs. Dynamic Dual Language Program Planning

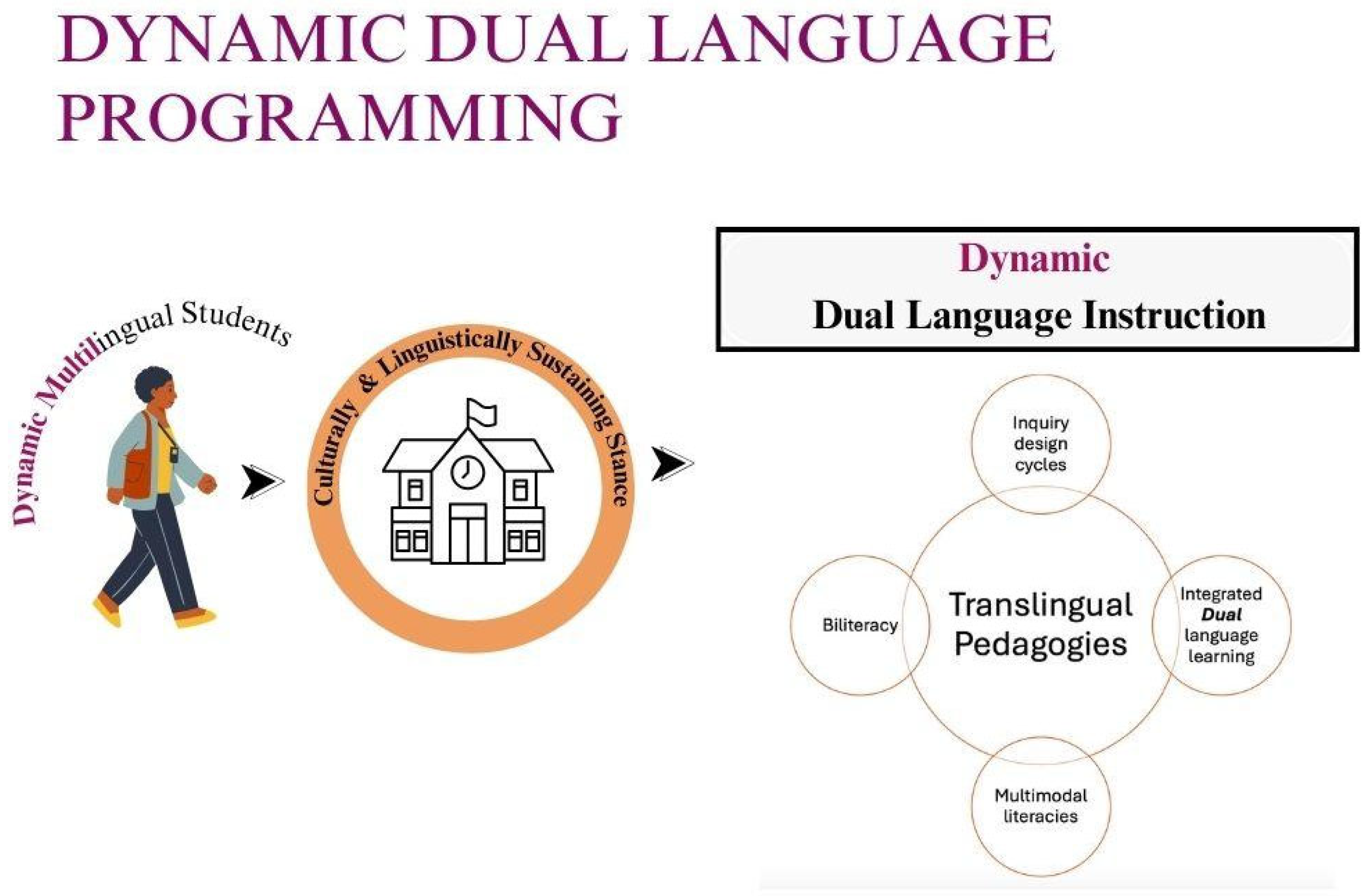

3. Conceptual Framework: Dynamic Dual Language Instruction for Dynamic Bilingual Learners

4. Implementing Translanguaging Pedagogies

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). English Learners in Public Schools. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. 2024. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgf (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Cummins, J. Rethinking the Education of Multilingual Learners: A Critical Analysis of Theoretical Concepts; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Canagarajah, S. Translanguaging in the Classroom: Emerging Issues for Research and Pedagogy. In Applied Linguistics Review; Wei, L., Ed.; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- García, O. Translanguaging and Latinx Bilingual Readers. Read. Teach. 2020, 73, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O.; Lin, A.M.Y.; May, S. Bilingual and Multilingual Education. In Encyclopedia of Language Education, 3rd ed.; May, S., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- García, O.; Ibarra Johnson, S.; Seltzer, K. The Translanguaging Classroom: Leveraging Student Bilingualism for Learning; Caslon: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gort, M. The Complex and Dynamic Languaging Practices of Emergent Bilinguals; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Makalela, L. Moving out of Linguistic Boxes: The Effects of Translanguaging Strategies for Multilingual Classrooms. In Language Epistemic Access: Mobilizing Multilingualism and Literacy Development; Kerfoot, C., Simon-Vandenbergen, A.-M., Eds.; Routledge: Bristol, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Salmerón, C. Elementary Translanguaging Writing Pedagogy: A Literature review. J. Lit. Res. 2022, 54, 222–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, T. Translanguaging as a Pedagogy for Equity of Language Minoritized Students. Int. J. Multiling. 2021, 18, 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. Arfarniad o Ddulliau Dysgu ac Addysgu yng Nghyd-destun Addysg Uwchradd Ddwyieithog [An Evaluation of Teaching and Learning Methods in the Context of Bilingual Secondary Education]. Unpublished. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wales, Cardiff, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.E.; Pacheco, M.B.; Khorosheva, M. Emergent Bilingual Students and Digital Multimodal Composition a Systematic Review of Research in Secondary Classrooms. Read. Res. Q. 2020, 56, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C. Multilanguage, Multipurpose: A Literature Review, Synthesis, and Framework for Critical Literacies in English Language Teaching. J. Lit. Res. 2017, 49, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslimani, M.; Hugo Lopez, M.; Noe-Bustamante, L. 11 Facts on Hispanic Origin Groups in the U.S. Pew Research Center. 2023. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/08/16/11-facts-about-hispanic-origin-groups-in-the-us/ (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Lindholm-Leary, K.; Borsato, G. Academic Achievement. In Educating English Language Learners: A Synthesis of Research Evidence; Genesee, F., Lindholm-Leary, K., Saunders, W., Christian, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 176–221. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, V.P.; Thomas, W.P. Validating the Power of Bilingual Schooling: Thirty-two years of large-scale, longitudinal research. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 2017, 37, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm-Leary, K. Bilingualism and Academic Achievement in Children in Dual Language Programs. In Lifespan Perspectives on Bilingualism; Nicoladis, E., Montanari, S., Eds.; APA Books: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm-Leary, K.; Genesee, F. Alternative Educational programs for English Language Learners. In Improving Education for English Learners: Research-Based Approaches; California Department of Education, Ed.; CDE Press: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 323–382. [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm-Leary, K.; Hernández, A.M. Achievement and Language Proficiency of Latino Students in Dual Language Programmes: Native English speakers, fluent English/previous ELLs, and current ELLs. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2011, 32, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, J.; Gorter, D. Towards a Plurilingual Approach in English Language Teaching: Softening the boundaries between languages. TESOL Q. 2013, 47, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Roldán, C.M. Translanguaging Practices as Mobilization of Linguistic Resources in a Spanish/English bilingual after- school program: An analysis of contradictions. Int. Multiling. Res. J. 2015, 9, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, M.B.; Miller, M.E. Making Meaning through Translanguaging in the Literacy Classroom. Read. Teach. 2016, 69, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, M.B.; Smith, B.E.; Deig, A.; Amgott, N.A. Scaffolding Multimodal Composition with Emergent Bilingual Students. J. Lit. Res. 2021, 53, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alim, H.S.; Paris, D. Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Genesee, F. Rethinking Bilingual Acquisition. In Bilingualism: Beyond Basic Principles: Festschrift in Honour of Hugo Baetens-Beardsmore; Dewaele, J.-M., Housen, A., Li, W., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2002; pp. 158–182. [Google Scholar]

- García, O. Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA/Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lightbown, P.; Spada, N. How Languages are Learned; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, W.E. Foundations for Teaching English Language Learners: Research, Theory, Policy, and Practice, 3rd ed.; Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, W.; Butvilofsky, S.; Escamilla, K.; Hopewell, S.; Tolento, T. Examining the Longitudinal Biliterate Trajectory of Emerging Bilingual Learners in a Paired Literacy Instructional Model. Biling. Res. J. 2014, 37, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, J. Who Speaks What Language to Whom and When? La Linguist. 1965, 1, 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. Mind and Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Escamilla, K.; Hopewell, S.; Butvilofsky, S.; Sparrow, W.; Soltero-González, L.; Ruiz-Figueroa, O.; Escamilla, M. Biliteracy from the Start: Literacy Squared in Action; Caslon Publishing: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, G. Cultivating Genius: An Equity Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy; Scholastic: Wilkinsburg, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Center to Support Excellence in Teaching (Understanding Language). Fundamentals of Language & Content Learning. 2021. Available online: https://ul.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/resource/2023-08/ILC%20Fundamentals%20Final.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Halliday, M.A.K. Toward a Language Based Theory of Learning. Linguist. Educ. 1993, 5, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, D. Literacy: An Introduction to the Ecology of Written Language; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, J.P. Sociolinguistics and Literacies: Ideology in Discourses, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Street, B.V. Literacy in Theory and Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Street, B.V. Social Literacies: Critical Approaches to Literacy in Development, Ethnography and Education; Longman: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hornberger, N. Opening and Filling up Implementational and Ideological Spaces in Heritage Language Education. Mod. Lang. J. 2005, 89, 605–609. [Google Scholar]

- Butvilofsky, S.A.; Hopewell, S.; Escamilla, K.; Sparrow, W. Shifting deficit paradigms of Latino emerging bilingual students’ literacy achievement: Documenting biliterate trajectories. J. Lat. Educ. 2017, 16, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravitch, D.; Riggan, M. Reason & Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Traditional Dual Language Classroom | Dynamic Dual Language Classroom | |

|---|---|---|

| Moment-to-moment | The teacher asks a content-centered question in the target language. A student responds with codeswitching. Before evaluating the response, the teacher asks the student to recast their statement in the target language. | Teacher: “What are the stages of the water cycle”? Student: “The stages are evaporation, condensación, precipitación and collection”. The teacher recognizes that the content area information is accurate and notes the student retained the content knowledge and delivered the information using both languages. The teacher gives the student credit for a correct answer and soon after helps the student make the cross-language connection between the suffix -ción (Español) and -tion (English). |

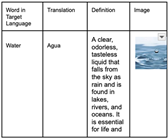

| Vocabulary Lesson | Teacher uses a slide deck to teach academic vocabulary in the target language using images for comprehensible input; students copy notes silently in a notebook using the target language. | The teacher uses a partner activity where students work together to determine the meaning of new vocabulary words in the target language and then organize these words into a four-column chart including the translated term, a definition, and an image. Students use multiple languages and registers to collaboratively decipher the meaning of new words in the target language. |

| Cognates | A student uses a false cognate in a written response during English writing time (e.g., record/recorder in “I record one time I went to the beach”.) The teacher corrects the multilingual student during a writing workshop by modeling how to spell the English word, “remember”. | The teacher plans for explicitly teaching the cognates appearing in a mentor text. The teacher has a cognate chart with visuals and examples displayed in the classroom throughout the unit. During shared reading, students find and record cognates in a journal with a definition and visual. The teacher uses journals and anchor charts as part of a multilingual classroom ecology where students are taught and encouraged to make cross-language connections by being cognate detectives. |

| Idioms | The teacher pre-teaches a new text by telling students what an idiom means in a target language. | The teacher uses a variety of strategies (e.g., Así se Dice [32] to allow students to negotiate the meaning of idioms across languages and to think critically before directly translating an idiom. When a text includes the idiom, “He rained on my parade”, the teacher asks students to collaborate to find a Spanish idiom that best matches the intended meaning. Students may land on “Hay una mosca en la sopa”. When students come to an agreement on a new idiom, they add it to the classroom idiom chart to compare and contrast idioms in multiple languages. |

| Instructional Approaches | Definition |

|---|---|

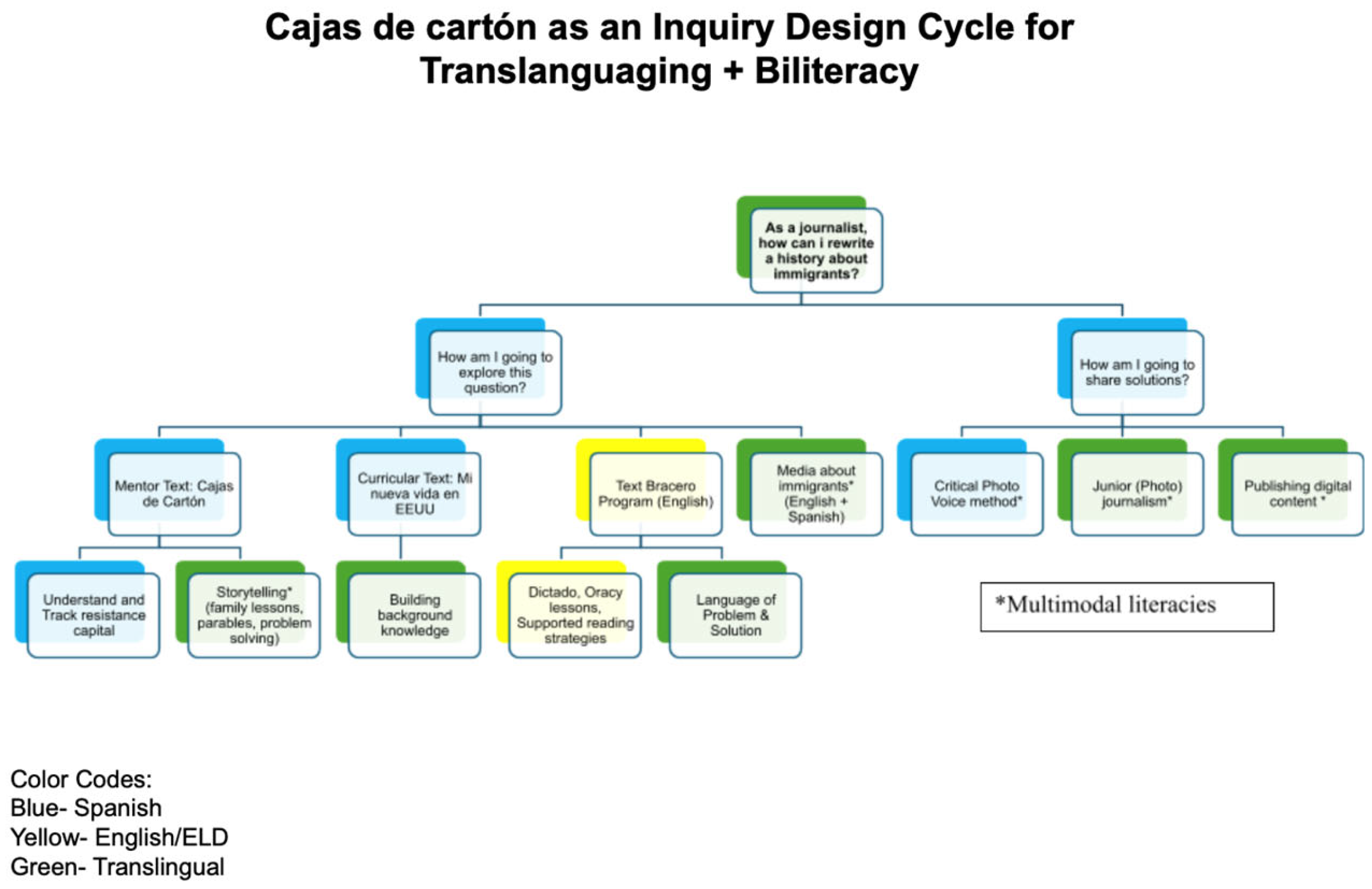

| Inquiry Design Cycles | Inquiry-based learning “scaffolds and integrates student learning and enables them to demonstrate that learning in differentiated, authentic ways” ([6], p. 72). Inquiry and translanguaging instructional design cycles engage students in exploring socially relevant topics and problem solving providing a context for natural language use and development through interaction. Culminating projects allow students to share solutions using multiple literacies. |

| Integrated Dual Language Learning | Integrated English Language Development refers to the established practice of providing English language development and sheltered instruction in the context of content area lessons (e.g., math, science, social studies, art, music, and language arts). Integrated dual language learning holds that English is not the exclusive system with academic registers. Languages other than English can and should be developed as content is provided in multiple languages, and disciplinary-specific discourse, from a functional linguistic perspective [34,35], can be taught in multiple languages. |

| Multimodal Literacies | The field of New Literacy Studies [36,37,38,39] promoted literacy as a social practice calling attention to diverse forms of learning and cultural ways of knowing and doing. This field emerged prior to the high stakes testing era (2001), which ultimately narrowed school-based literacies to the tested subjects of math, reading, and writing in standard English only. Adopting multimodal literacies seeks to bridge the literacy divide and disrupt what counts as (more and less) powerful forms of literacy [40]. In the school setting, this includes multimodal ways of acquiring and demonstrating new knowledge and skills. Multimodal literacies create a more interactive, inclusive, and accessible context for natural language use compared to traditional school-based, standardized literacies. |

| Biliteracy | Classrooms designed for biliteracy invite teachers to pair Spanish and English literacy units to allow students to make connections across languages and to use both languages within a paired literacy lesson. This involves looking for strategic opportunities to integrate bilingual texts and opportunities to support reading, writing, oracy, and metalanguage in support of Spanish language arts and integrated, literacy-based English language development. Findings from research on paired literacy instruction in elementary classrooms indicate that students participating in paired literacy environments attain higher literacy outcomes in English and Spanish than traditional bilingual instruction with separate language environments [29,41]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caires Hurley, J.; Dougherty, J.; Ibarra Johnson, S. A Conceptual Framework Supporting Translanguaging Pedagogies in Secondary Dual-Language Programs. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101052

Caires Hurley J, Dougherty J, Ibarra Johnson S. A Conceptual Framework Supporting Translanguaging Pedagogies in Secondary Dual-Language Programs. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(10):1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101052

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaires Hurley, Jaclyn, Jessica Dougherty, and Susana Ibarra Johnson. 2024. "A Conceptual Framework Supporting Translanguaging Pedagogies in Secondary Dual-Language Programs" Education Sciences 14, no. 10: 1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101052

APA StyleCaires Hurley, J., Dougherty, J., & Ibarra Johnson, S. (2024). A Conceptual Framework Supporting Translanguaging Pedagogies in Secondary Dual-Language Programs. Education Sciences, 14(10), 1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101052