Abstract

This study examined the experiences of 15 refugee school teachers in Athens, focusing on their strategies for working with culturally diverse adult students. Through semi-structured interviews, the research investigated the evaluation of intercultural education that is imparted to adult refugees, the challenges in the program’s implementation for adult refugees, the importance and the necessity of intercultural competence for instructors when working within refugee structures, and the possible ways of influencing the ethnic diversity of adult refugee immigrants that affect teachers’ perspectives regarding their education and social integration. The findings reveal a mix of progress and challenges in cultural education, exacerbated by the global financial crisis and infrastructure deficiencies. Intercultural competence emerges as vital for fostering inclusive learning environments, while embracing ethnic diversity shifts the focus from assimilation to celebration. Success indicators include cultivating a collective consciousness, promoting interaction between cultures, fostering empathy, and providing adequate resources. These insights offer valuable implications for enhancing refugee education and integration efforts in Athens and beyond.

1. Introduction

The recent influx of refugees has had a significant impact, with Greece accommodating over 186,000 refugees and asylum-seekers by the end of 2019 [1]. Additionally, since the 1990s, Greece has been a destination for migrant workers, primarily from Eastern European and Balkan nations [1]. The emergence of multiculturalism has led to a transformation in the educational landscape, shifting from a previously monocultural focus to one characterized by interculturalism [2]. Over recent years, the Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs has been actively engaged in implementing action initiatives and procedures to facilitate the educational integration of these demographic groups. A primary objective of education is to underscore the rich diversity of humanity and foster an understanding of the commonalities and interdependencies among individuals [3]. In contemporary societies, there is a heightened emphasis on acknowledging the diversity of others within the framework of postmodern thought. A defining aspect of postmodernism is the critique of issues pertaining to racism and xenophobia, particularly in large urban centers, which have been integrated into its conceptual framework. Moreover, the principles espoused by the postmodernist movement wield considerable influence in the ongoing discourse surrounding knowledge and education [4].

As posited by Wilson and Hayes [5], adult education assumes a pivotal role in facilitating the integration and societal inclusion of migrants and refugees. Central to its ethos is the continuous encouragement of learners to pursue fresh knowledge and refine their skill sets continually. Indeed, the advancement and advocacy of intercultural education among marginalized social cohorts are predominantly realized through adult education initiatives. Given the swiftly evolving landscape of immigration and refugee affairs, there exists an imperative to properly train teachers in matters of intercultural education and foster the seamless assimilation of these groups, i.e., refugees, into contemporary societal contexts [6]. In this direction, it is very interesting to examine teachers’ views regarding their role in teaching adult students in multicultural contexts.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Definition of Refugees and Immigrants

The terms “refugee” and “immigrant” have distinct and different meanings. According to Article 1 of the Geneva Convention [7], a refugee is defined as “any person who, due to his ethnic origin, his religion, his nationality, his association with a particular social group, has a well-founded fear of persecution or his political beliefs, is outside the country of which he is a national and who cannot, or because of such fear does not wish, to be under the legal protection of that country”. Refugees usually enter the host countries illegally and seek asylum. If approved, they are considered as recognized refugees and are under international protection status.

The right to asylum is enshrined in the Geneva Convention and was signed by 138 countries around the world. An immigrant is defined as someone who leaves his or her country of citizenship in order to settle in another country in search of a better future. In some cases, they choose to move to join family members or for educational reasons [8].

Refugees and immigrants are at high risk of social exclusion because they are unable to access the social rights of a citizen. “Education is a powerful weapon to combat social exclusion and initiate social change” [9]. The mass movement of refugees and immigrants to other national states brings about changes in societies that acquire a multicultural texture and structure.

2.1.1. The Context of Intercultural Education in Greece

Intercultural education appeared as an educational method in 1980 [10]. Intercultural education is the pedagogical response to the problems of an intercultural nature that arise in a multicultural and multinational society [11].

The four basic principles that are simultaneously the goals of intercultural education are as follows:

- -

- The formation of positive perceptions of the differences between cultures;

- -

- Solidarity;

- -

- The respect of other cultures as equals;

- -

- Peace education and the non-nationalist way of thinking.

These principles are considered the basis of communication and relationships between people and with their physical and social environment, which is constantly evolving into a complex structure [12].

Since 1989, when the migrant movement in Greece and throughout Europe commenced a gradual expansion, Greek society has undergone a series of significant transformations and disruptions. Given the multifaceted and intricate nature of immigration, it engenders interactions between the indigenous populace and immigrants across various dimensions (economic, social, cultural, etc.), thereby delineating the contours of the emergent social landscape. Presently, one out of every ten Greek residents constitutes an immigrant, thus contributing to the evolving demographic profile of the nation [13]. Unlike other European counterparts, Greece has experienced an exceptional transition from a society primarily characterized by emigration to one increasingly defined by immigration [13]. Given Greece’s status as a multicultural society, all ethnic cohorts must be afforded equitable opportunities for engagement in social and educational progress, while simultaneously upholding the utmost respect for their respective identities [14].

It is commonly recognized that there exists a notable absence of a well-defined and legally structured immigration framework, alongside inadequate social assistance for immigrants in Greece, hindering their integration [15]. This is despite numerous studies attesting to immigrants’ considerable potential for social inclusion [13].

The point above has been proven by the findings of a study, which found that all immigrants who participated in the research acquired proficiency in the Greek language through informal means, primarily through exposure to Greek media and concerted personal endeavors. While some individuals supplemented their language acquisition by attending formal classes, their responses regarding the reception received in the local community (of the area they lived in) and their social interactions with Greeks indicated that while some connections were maintained, they were often characterized as superficial and sporadic [16].

In numerous instances characterized by xenophobic and racist attitudes, immigrants often find themselves perceived as representatives of their respective national origins, thereby subjecting them to stereotypical categorization. This, in turn, results in verbal assaults, skepticism, disdain, and apprehension [17]. The result is that negative phenomena are created in society, such as violence and a lack of the smooth coexistence of immigrants with Greeks, because, essentially, immigrants are not acknowledged as individuals possessing unique attributes and qualifications but rather as representatives of a collective identity. The absence of mutual understanding further hinders the development of social interactions between the native populace and newcomers. Significantly, the prevalence of discriminatory behaviors and xenophobia tends to decrease with increased interpersonal engagement between indigenous residents and immigrants [16]. Gioka contended that ameliorating discrimination and bolstering the social confidence and self-esteem of immigrants are crucial for facilitating their seamless integration into society. This perception exhibits a pronounced skepticism towards the governmental apparatus and individuals in authoritative positions, frequently expressing apprehension regarding their legal status [16].

Greeks value linguistic and cultural variety and demonstrate an interest in the languages and customs of migrant students without contesting the prevailing culture of the classroom or the nation as a whole [14]. According to Moissidis and Papadopoulou, it takes a long time for Greek society to mature, overcome prejudice and rigid regulations, and open the way for immigrants to fully participate in all local organizations [13]. The refugee crisis, which hit a crucial phase at the start of 2015, is currently one of Greece’s greatest problems. Due to its strategic location, Greece has been a prominent destination for refugees in recent years; 29,404 refugees entered Greece in 2018.

The General Education Board bears the duty of appointing educators to interact with refugee communities, without stipulating specific qualifications [18]. This practice is considered essential, as emphasized by Paleologou and Evangelou, who echoed Oberg’s assertion that adapting to a new environment can lead to considerable psychological strain. The lack of standardized directives governing the preparation of teachers with similar backgrounds in intercultural and bilingual education poses challenges in identifying the instructional methodologies that educators possessing analogous qualifications may employ [19,20].

2.1.2. Intercultural Adult Education

Intercultural education embodies a facet of humanistic pedagogy focused on the nuanced intricacies of human diversity, particularly concerning individuals originating from diverse cultural backgrounds marked by differences in language, religion, and other societal dimensions [21]. Nikolaou emphasized the fundamental philosophy of intercultural education, which revolves around nurturing mutual respect, solidarity, acknowledgment, and, ultimately, the equitable inclusion of all individuals as valued members of society [22]. Additionally, Gotovos posited that intercultural education aligns closely with the foundational principles of social cohesion, justice, and equality among human populations. In elucidating the fundamental tenets and prerequisites inherent to this educational domain, Gotovos delved into the notion of egalitarianism across diverse cultural and social spectra. Emphasis is placed on fostering reciprocal interaction and effective communication among populations possessing varied cultural backgrounds. Furthermore, paramount importance is attributed to the recognition and adoption of equal opportunities for all students, on the part of teachers, regardless of their geographical origin or societal standing. At the heart of this paradigm lies the facilitation of equitable educational opportunities, ensuring the seamless participation of each learner in the educational environment. Such an inclusive approach promoting equality enables educators to leverage their socio-cultural heritage and abilities as they strive to acquire new knowledge and skills [23].

Challenges and Necessity of Intercultural Education

The imperative for intercultural education is accentuated by contemporary global challenges which require the development of the necessary cognitive background and skills to be able to effectively manage individuals diverging from the prevailing societal norms regarding nationality, heritage, race, and other defining characteristics. Otherwise, there will be an insufficiency that precipitates the onset of conflicts, apathy, intolerance, aggression, and exclusion, all of which can be alleviated through educational endeavors, cultural engagement, and the celebration of diversity. A comprehensive conceptualization of education, serving as the cornerstone for discourse on intercultural education, includes the multifaceted influences shaping individuals and communities, nurturing their development [24], and enabling the realization of their potential as enlightened and innovative contributors to their social, national, cultural, and global contexts. Such educational initiatives facilitate proactive self-realization, the cultivation of a distinct and enduring identity, and the attainment of autonomy, empowering educators to pursue personal and societal objectives. In this context, education encompasses a spectrum of activities, such as information and training on intercultural issues, aimed at guiding individuals towards the realization of their latent capabilities, encompassing all influential factors governing their attitudes, behaviors, and interactions within the broader social and global milieu [25].

Initiatives in Greece

The educational pathways pursued by adult immigrants and refugees in their efforts to acquire proficiency in the Greek language demonstrate considerable diversity. Various governmental and non-governmental organizations are engaged in this endeavor, some falling under the purview of the Ministry of Education, while others operate independently [26]. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) play a significant role, often initiated through private initiatives and frequently involving active engagement from local community members and citizens. Additionally, there are bodies with private legal entity status dedicated to serving the public good.

Examples include the following:

- -

- Doctors of the World;

- -

- The Greek Red Cross;

- -

- Greek high schools;

- -

- The Pyxida Intercultural Center of the Hellenic Council for Refugees, etc.

Free Greek language courses serve as a common incentive for their endeavors, with each organization utilizing distinct funding mechanisms. Financial support for these efforts originates from various sources, including the European Central Bank, the European Refugee Fund, national governments, and individual donors [27]. Established in September 2002, the collective comprises approximately 40 member organizations [28]. It is noteworthy that the scope of intercultural education extends beyond mere Greek language instruction, encompassing broader activities such as providing free legal assistance throughout all stages of the asylum process and assisting individuals seeking repatriation. Moreover, interpretation services are offered to asylum authorities and a range of other entities, including international organizations, non-governmental organizations, hospitals, public services, and educational institutions.

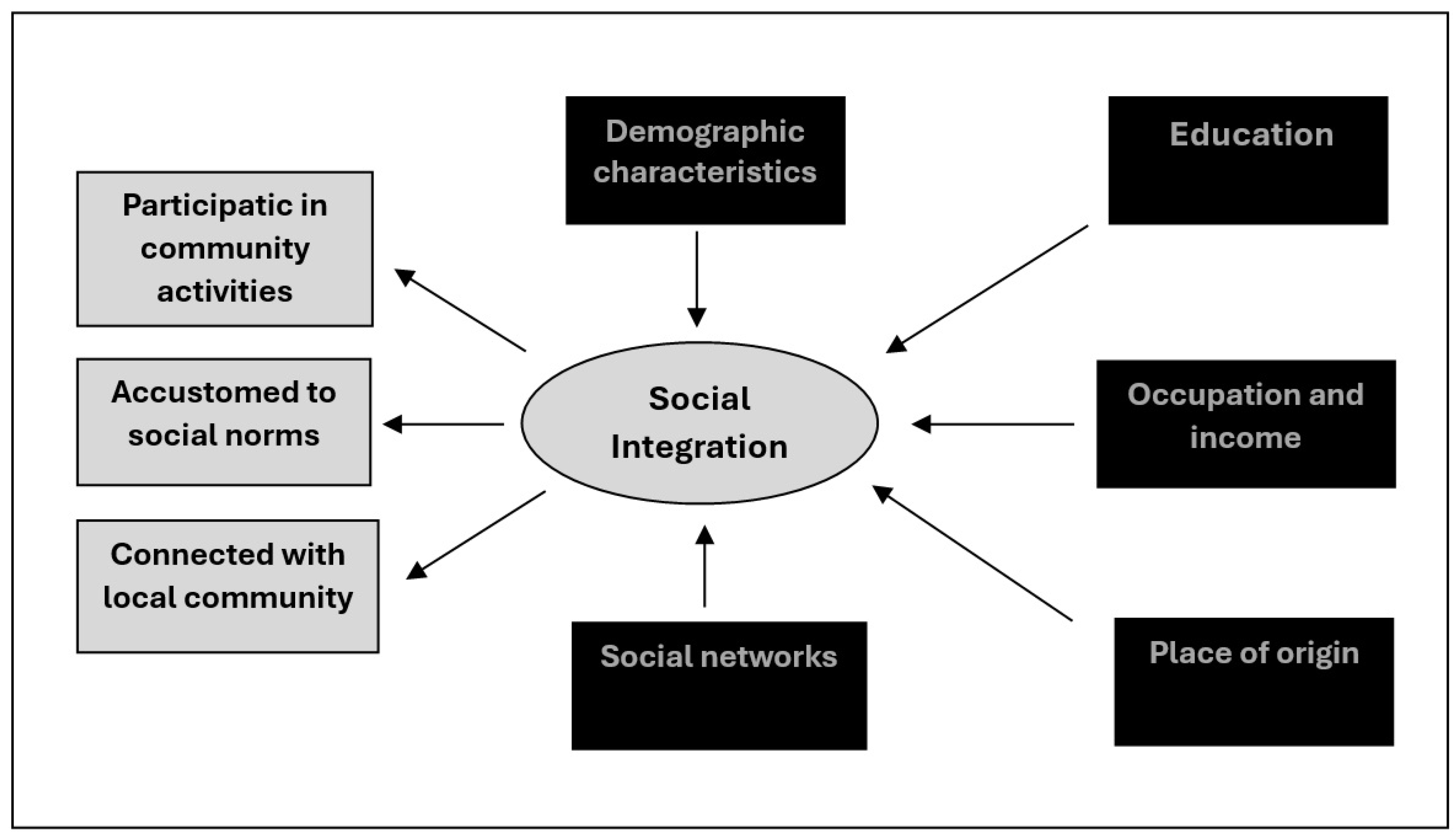

The primary aim of these organizations extends beyond the provision of Greek language instruction to newcomers; they also prioritize safeguarding their rights and facilitating their full participation in society. One such initiative, Odysseus, initiated in 2007 and overseen by the Foundation for Youth and Lifelong Learning (INEDIVIM), offers a complimentary program accessible to individuals of all racial and ethnic backgrounds, including immigrants, EU citizens, and third-country nationals. Alongside language instruction, Odysseus’ participants delve into Greek history, culture, and the political and social structure of Greece. The overarching goal of the program is to facilitate language acquisition among the participants and their families, while concurrently nurturing the development of the social and intercultural competencies that are crucial for their integration as active members of society (refer to Figure 1 in the text). This includes equipping them with the requisite skills to enable better communication with other members of the community and their active participation in social, educational, and cultural events [29].

Figure 1.

Social integration.

It should be noted that the efforts mentioned above are implemented by, among others, the Foundation for Youth and Lifelong Learning, a non-profit organization that is financially and operationally independent. As part of the operational program “Education and Lifelong Learning” of the Ministry of Education, Research, and Religions, courses are offered around the country and jointly sponsored by the European Union (European Social Fund, ESF) and the country’s resources [30].

Of course, the programs must be combined with effective teaching techniques to achieve positive results. Discussion, role-playing, improvisation, and the application of learned concepts to real-world scenarios are cited as effective pedagogical techniques for the education of adult students [31]. A primary objective of organizations such as the Foundation for Youth and Lifelong Learning of the European Union, which promote intercultural education, is to combat the social marginalization of asylum-seekers and refugees, facilitating their integration into Greek society by providing opportunities for them to attain proficiency in the Greek language [32]. Courses typically span three to four months, during which, Greek language instructors aim to train adult students who volunteer to learn the language’s fundamentals, enabling them to convey linguistic and grammatical nuances to their peers. Funding for this initiative is now provided by the European Refugee Fund, which is accessible to all member states of the European Union [30]. In instances where no funding mechanism is available, the organization offers Greek language classes regularly. Furthermore, the organization covers the cost of language exams for students, enabling them to graduate with a recognized credential. The vice president of the group noted that METAdrasi was established to address longstanding deficiencies in Greece’s immigration system, which have resulted in the country facing penalties from European courts [33]. In addition to providing free Greek language instruction, the Immigrant Integration Center of the City of Athens also offers adult classes in computer literacy and employment counseling. Recently inaugurated by the Municipality of Athens, the Immigrant and Refugee Coordination Center aims to serve as a centralized coordinating body for the municipality, facilitating the development of a strategic plan to enhance service delivery to immigrants and refugees, as well as their participation in urban life and the preservation of social cohesion. Established in June 2017, the Coordination Center has operated successfully with support from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, under the auspices of the “Coordination Center and Observatory of Immigrants and Refugees” [34].

Adult Refugee-Immigrant Education Structures in Greece

In addition to the non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other private bodies mentioned in the previous section, the following agencies operate in Greece for learning the Greek language as a second foreign language.

- -

- Immigrant integration centers (ICMs). These were established by Law 4368, Official Gazette 21A/2016 [35]. They are branches of the youth centers of the municipalities. At KEM, Greek language courses and elements of Greek history and culture are implemented for adult refugees and immigrants.

- -

- Second chance schools (Article 67 of Law 4763/2020) [36]. Preparatory classes for learning the Greek language for immigrants and refugees over 18 years of age operate in them.

- -

- Greek language centers. These are supervised directly by the Ministry of Education, cooperate with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, prepare educational programs, and provide supporting material, both theoretical and practical, for the teaching of Greek as a second foreign language.

- -

- Centers for lifelong learning. These are subordinate to the Ministry of Education, operated under Law 4763/2020, and provide Greek language lessons to adult refugees and immigrants.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Purpose and Questionnaire

The purpose of this research was to investigate the role of instructors working with adult refugee-immigrants in managing cultural diversity within Athens’ refugee structures. The study aimed to gain a deeper understanding of the challenges and opportunities that arise in the education of adult refugees and the significance of intercultural competence among refugee educators. The research sought to explore the perspectives of these teachers regarding the cultural education provided to adult refugees and its impact on their social integration. Additionally, the study aimed to identify the challenges faced during the implementation of educational programs for adult refugees. To achieve these objectives mentioned above, the following open-ended questions were posed to the participating teachers.

- i.

- How is cultural education imparted to adult refugees within refugee frameworks evaluated?

- ii.

- What are the main challenges and issues that emerge during the implementation of education programs for adult refugees?

- iii.

- Why is intercultural competence essential for instructors working within refugee structures?

- iv.

- In what ways, if any, does the ethnic diversity of adult refugee-immigrants influence your perspective as a teacher regarding their education and social integration?

- v.

- From your viewpoint as an adult refugee educator, what outcomes from the intercultural education program do you consider indicative of its success?The thematic analysis revealed the following five themes:

- i.

- Evaluation of cultural education;

- ii.

- Impact of the global financial crisis;

- iii.

- Implementation of educational programs;

- iv.

- Necessity of intercultural competence;

- v.

- Embracing ethnic diversity.

3.2. Methodology

The selected data collection method for this study was semi-structured individual interviews, which are deemed to be highly suitable for qualitative research [37]. This approach fosters direct interaction between the researcher and the participants, facilitating a profound exploration of the research questions and encouraging the participants to articulate their opinions verbally [38]. The organic flow of conversation inherent in this method enables richer data collection [39], which aligns well with the thematic analysis framework for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns within qualitative data [40]. Before conducting the main interviews, a preliminary phase involved pilot interviews with a small sample of adult migrant/refugee educators. These pilot interviews served to acquaint the researcher with the interview process, allowing for adjustments to the questions to avoid overwhelming the participants while capturing valuable insights [41].

Initial contact with each adult educator was established via telephone, during which clarifications were provided regarding the purpose and goals of the survey, the necessity of their participation, and assurances of privacy protection. Permission to record each interview was also obtained. The research was conducted during February and March of 2022. The semi-structured questionnaire initially comprised inquiries about the demographic profile of the adult educators (e.g., age, education, marital status) followed by open-ended questions concerning the trainers’ perspectives on intercultural education and the social integration of migrants and refugees. More specifically, the characteristics of the educated immigrant-refugee adults in terms of their nationality were as follows:

- -

- 37% from Syria;

- -

- 27% from Afghanistan;

- -

- 20% from Iraq;

- -

- 3% from Palestine;

- -

- 3% from Somalia; and

- -

- 10% from various countries.

Regarding their academic level,

- -

- 25% were primary school graduates;

- -

- 45% were secondary school graduates;

- -

- 20% were graduates of higher education; and

- -

- 10% did not hold any degree.

The ensuing discussions evolved into constructive dialogues within a positive and welcoming environment. Throughout each interview, the researcher diligently recorded notes in her notebook, maintaining a discreet exploratory attitude while respecting the responses of all participants [41].

Convenience sampling, a non-probability method, was employed in this research, whereby units were selected according to the ease of access for the researcher. Factors such as geographical proximity, availability at the time of the study, and willingness to participate influenced the selection process [42]. The sample comprised 15 refugee-immigrant educators working in refugee structures in Athens, 9 of whom held fixed-term contracts while 6 had permanent positions. The sample included 12 men and 3 women. The age distribution indicated that nine participants were aged between 31 and 39 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample.

The 15 teachers were all graduates of higher education (8 teachers in primary education and 7 teachers in secondary education). Six had attended annual training programs in intercultural education. Four had attended annual training programs in adult education.

Regarding their teaching experience in teaching Greek as a second or foreign language, six of them had worked for 6 to 10 years. They worked full time with a permanent job, and they worked in the same organization and had always held the same role/position. The remaining nine had teaching experience of one to five years. They worked on fixed-term contracts and always in the same role/position, but in different organizations.

Regarding teaching experience, seven educators had 1 to 5 years of experience teaching Greek as a second/foreign language, primarily to adult learners, while the remaining eight had 6 to 12 years of experience, primarily in primary and secondary education settings.

3.3. Validity and Trustworthiness

The methodological approach employed in this study aligns with the requirements of qualitative research, aiming to interpret the ever-changing and evolving social reality [43]. The research process endeavors to holistically explore social phenomena, considering both convergent and divergent features, thereby ensuring a comprehensive and global understanding.

Validity, a crucial aspect of research, is ensured by aligning the data collection instrument with the research’s intended goals [44]. Special attention was devoted to enhancing the research’s validity throughout its design and implementation. Measures such as safeguarding the anonymity of the survey participants’ personal information through password-protected identifiers during the interviews and data processing were implemented. Moreover, the researcher’s intervention during the interviews was minimized to prevent any potential influence or interference, thereby preserving the integrity of the data. Reliability, another essential element, was upheld by ensuring the authenticity and objectivity of the acquired data [45]. By capturing essential aspects of the subject’s reality, the participants’ responses were deemed to be potentially representative samples. Additionally, evaluating similar methodological techniques in the context of theoretical documentation contributed to achieving the highest feasible level of research dependability.

3.4. Restrictions

Despite concerted efforts, the current research faced several hindrances that remained insurmountable. Firstly, a notable limitation pertains to the small number of participating refugee instructors. This scarcity is attributed to the nascent stage of adult education for culturally vulnerable groups within the Greek educational system, posing challenges in recruiting suitable study subjects. Additionally, the small sample size, compounded by the purposeful sampling approach employed, precluded the generalization of results beyond the specific context of this study. Moreover, the inability to triangulate the findings with alternative methodological approaches or additional data collection instruments represents another constraint. Triangulation, a valuable technique for enhancing research validity, was hindered due to the study’s reliance on a single data collection method. This limitation restricts the breadth and depth of insights that could have been gleaned from complementary research methods.

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation of Cultural Education

The evaluation of cultural education provided to adult refugees in Greece revealed a mixed picture. Teachers reported an initial degradation of intercultural education, but they also noted a gradual improvement over time. However, compared with some European nations, Greece still lags in intercultural education standards.

“One of the foremost negative effects we encountered initially was the inadequate state of intercultural education in Greece. The degree of inadequacy of intercultural education was lower than expected. While we’ve observed some progress over the years, it has yet to reach the standard we aspire to. Regrettably, we still lag behind certain European nations in this aspect.”(Instructor 7)

4.2. Impact of the Global Financial Crisis

The global financial crisis had negative repercussions on educational programs, exacerbated by deficiencies in the logistical infrastructure. Additionally, the decline in educational quality was attributed to a lack of teaching experience and training among educators. Another significant factor affecting the programs’ goals was the temporary contracts and the lack of interventions for the permanence of teachers who deal with intercultural education, a fact that hinders the acquisition of experience and creates insecurity among educators. Moreover, the absence of a single European intercultural education program placed considerable pressure on the national educational system, resulting in inadequacy, fragmentation, and challenges in meeting the diverse needs of adult refugee learners.

4.3. Implementation of Education Programs

In the implementation of education programs for adult refugees, several primary issues emerged, such as problems of coexistence between native and refugee adult students, and the prevalence of frequent absences, abstentions, and interruptions in the learning process, as highlighted during the interviews with the teachers. One significant challenge was the minimal coexistence and contact between native students and trained refugee-immigrants, primarily resulting from separate teaching departments, which limited opportunities for meaningful interaction.

“We noticed that there’s a real lack of interaction between our native students and the refugee-immigrants we teach. Unfortunately, separate teaching departments minimize their chances of coexistence. We believe fostering meaningful contact is crucial for building understanding and empathy between the two groups.”(Instructor 5)

Another pressing concern was the prevalence of frequent absences, abstentions, and interruptions in the learning process, hindering the progress of refugee learners. Moreover, negative attitudes toward education and involvement were observed among some adult refugees, often stemming from their low socioeconomic status and limited educational background [46]. The difficulty of communication between the teachers and the refugee students worked negatively to a certain extent, such as delays in the learning process. The results are identical to those of a study in which communication proved to be the most important obstacle, as there were no translators or interpreters to facilitate communication between the educators and the trainees [47].

Lastly, assisting adult refugees in adjusting to their new surroundings in the school context proved to be a formidable task, given the presence of already developed personalities and occasional disagreements among the trainees.

4.4. Necessity of Intercultural Competence

The factors necessitating the intercultural competence of adult refugee educators became evident through the insights shared by the teachers during the interviews. Continuous education, awareness, and preparation of the teachers were identified as crucial prerequisites for effectively dealing with the complexities of cultural diversity within the context of a volatile international environment [48].

“As educators, we must constantly update our knowledge and understanding of various cultures. Only then can we truly support our adult refugee students in their journey of integration.”(Instructor 2)

The role of teachers was acknowledged to be complex and demanding, requiring specialized knowledge, teaching skills, and skills in designing intervention programs which can be adapted to the unique needs of adult refugee learners. Intercultural competence and teaching skills emerged as essential qualities, enabling educators to foster an inclusive and supportive learning environment for students from diverse cultural backgrounds. The results are identical to those of research in which the requirement for the implementation of new teacher training programs was highlighted, where they could integrate both the strategies for teaching the new syllabi and the needs of the teachers with the ultimate goal of adapting to the modern intercultural reality [49]. By embracing intercultural competence, teachers can empower their students and foster a sense of belonging in the host country’s educational landscape.

4.5. Embracing Ethnic Diversity

The influence of ethnic diversity on perspectives regarding education and social integration among adult refugee educators was a key area of exploration during the interviews. As reported by the teachers, there has been a notable shift from the traditional approach of “assimilation” to embracing the concept of “difference” when integrating refugees into the host country’s society.

In parallel, Instructor 3 said the following.

“In northern Europe, for example Sweden, they invest in the training of trainers with the aim of being able to meet the demands of intercultural education and multicultural society. On the other hand, in Greece, training is carried out piecemeal with non-mandatory seminars. Teachers are recruited into adult refugee education structures without specialist knowledge of student management.”

Also, Instructor 4 emphasized that

“In Germany and Sweden, the education structure determines the individual study program, according to the needs of each adult refugee, while in Greece, they are drawn up by the Ministry of Education, and are specific and predetermined for all refugee adult learners.”

Instructor 7 highlighted this shift:

“Our focus has shifted from asking refugees to abandon their cultural identities to celebrating and respecting their diversity. It’s crucial to create an inclusive environment that appreciates and integrates various cultural backgrounds.”

Additionally, teachers discussed the need to adjust their cultural lenses to accommodate the changes in the culture, perspectives, mindset, and behavior of adult refugee-immigrant students. Understanding and empathizing with the unique challenges faced by these students are seen as essential for promoting successful integration. Furthermore, teachers recognized the importance of using appropriate educational models that provide equal opportunities for all adult students, regardless of their cultural backgrounds.

Some of the models are “station teaching” and “teaming”. In “station teaching”, the lesson is divided into three distinct parts, with the students rotating between three stations. At two stations, the teachers provide direct instruction, while at the third, the students work independently on related tasks, promoting small-group interaction and active participation. In contrast, “teaming” involves both teachers working together to lead whole-class instruction, sharing responsibilities equally. This can include jointly delivering lectures, presenting opposing views in a debate, or demonstrating different approaches to problem-solving. Both models emphasize cooperative planning and execution, ensuring diverse teaching methods and enriching the learning experience for students [50].

By adopting these models, educators aim to foster an environment where all learners can thrive and actively participate in the social and economic fabric of the host country.

The indicators of success in the intercultural education program for adult refugee educators were illuminated through the perspectives shared by the teachers during the interviews. One vital aspect highlighted was the cultivation of a collective consciousness, aimed at reducing social inequalities and injustices while fostering reciprocity and solidarity among diverse communities:

“A successful program goes beyond imparting knowledge; it empowers individuals to stand against discrimination and advocate for social justice.”(Instructor 5)

Encouraging interaction between different cultures while respecting their unique identities was also considered a crucial indicator of success. By creating an environment that celebrates diversity, teachers aim to promote mutual understanding and cooperation among students from various cultural backgrounds. Furthermore, fostering empathy and an emotional understanding of immigrants and refugees emerged as a significant measure of success in intercultural education:

“When students develop empathy, they become active allies, contributing to a more harmonious and inclusive society.”(Instructor 5)

Effective communication, dialogue, and a genuine respect for diversity were noted as essential components of successful intercultural education programs. These aspects facilitate meaningful connections and bridge the gaps between different cultures, promoting mutual appreciation and learning. Finally, teachers acknowledged that providing adequate material and technical infrastructure, along with appropriate educational intervention programs, is vital for achieving success in intercultural education. These resources create an enabling environment that supports the learning and integration of adult refugee learners.

5. Discussion

Through an in-depth analysis of the research data, it is evident that instructors working within adult refugee-immigrant educational structures develop a nuanced understanding of and appreciation for multiculturalism and cultural diversity, recognizing the positive contributions these facets offer to the learning environment.

Contrary to the notion of a singular cultural model, the findings underscore the significance of experiential learning in enhancing intercultural awareness and effectively instructing refugee migrants [51,52]. Moreover, the responsibility for facilitating the successful social integration of migrant refugees lies with the host country, a sentiment echoed in prior research by Miera [53]. That study emphasized the challenges posed by the low educational and economic status of adult refugee-immigrant students, exacerbated by the prevailing social and cultural stereotypes among both immigrants and members of the mainstream culture.

The findings resonate with the work of Karkkainen [54] and highlight the importance of educational institutions in promoting the integration of students from immigrant and refugee backgrounds. Suggestions for interventions and improvements provided by educators offer valuable insights, indicating shortcomings such as delayed recruitment, inadequate teacher training, and a dearth of appropriate educational materials, particularly in the realm of language learning [55].

Therefore, solutions must be identified to solve communication problems between teachers and adult refugee students, such as the presence of translators and reinforcement teachers, and teaching on foreign language learning.

Despite these challenges, the overarching goals of Greek language instruction and social integration are being pursued within educational systems, albeit with room for improvement. The limited interaction between international and native students contributes to the perpetuation of stereotypes and prejudices, hindering the integration process [56].

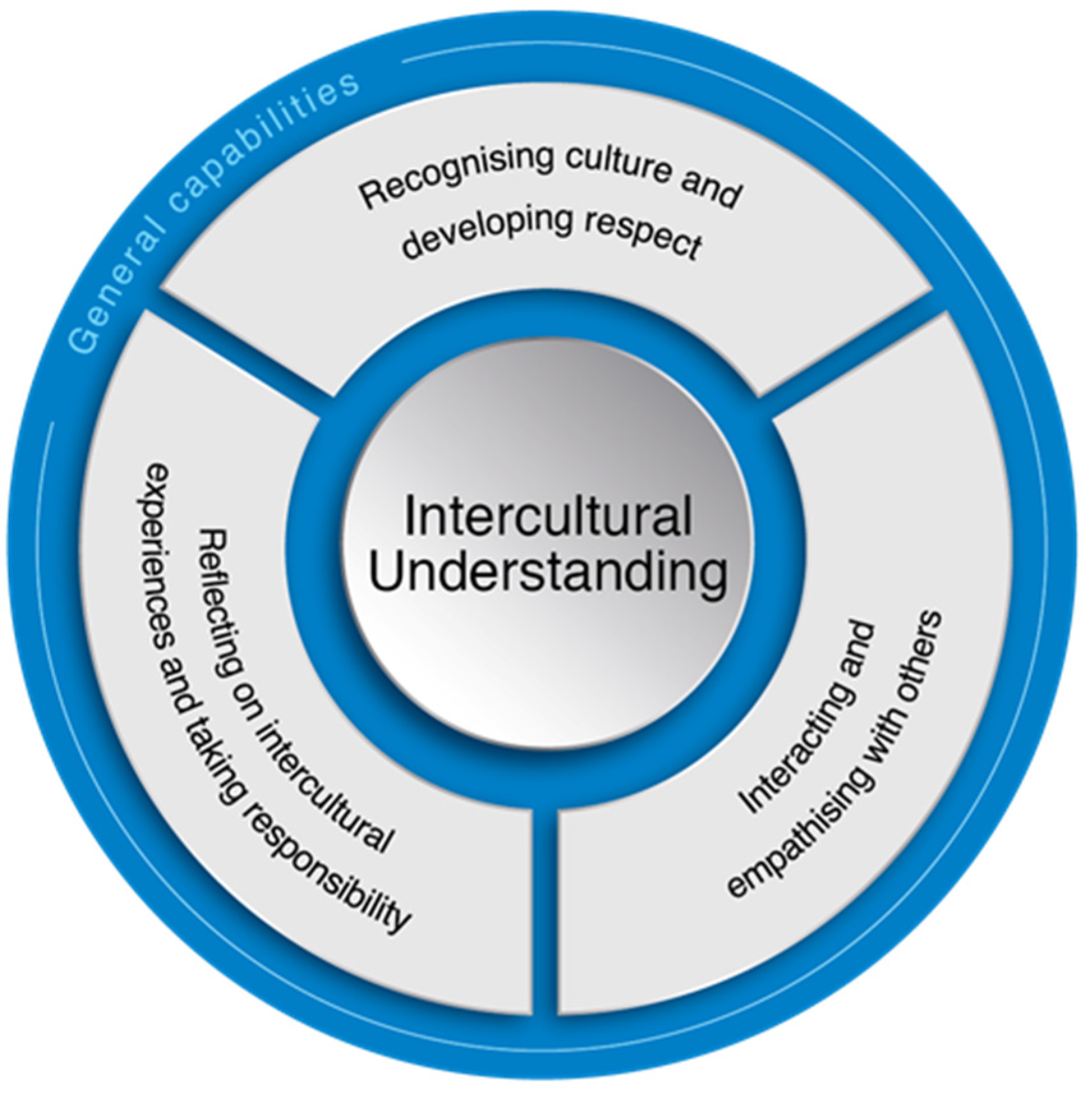

The multifaceted role of educators underscores the necessity of acquiring intercultural competence, which involves employing diverse pedagogical strategies to facilitate effective intercultural communication. Central to this role is the cultivation of respect for the students’ language and culture, along with an awareness of their unique needs, patience, high expectations, and avoidance of underestimation [56] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Intercultural understanding and respect [57].

Equal treatment of native and refugee adult students should be a priority for educators in the learning process. At the same time, they must seek to strengthen strong relations between the two groups through cooperative activities, so that solidarity and respect for diversity, in an intercultural context, are highlighted.

6. Conclusions

The adult refugee-immigrant learner occupies a central role in the educational process, wherein discourse, communication, and immersive methodologies are employed within the classroom setting. Adult learners, being inherently more perceptive than their younger counterparts, demonstrate maturity and a keen awareness of the practical necessity of acquiring the Greek language for immediate communication and vocational purposes.

Nevertheless, adult learners also contend with heightened responsibilities and concerns, rendering the learning process more challenging due to their pre-existing cognitive development acquired in their countries of origin. Intercultural education serves as a pivotal tool for facilitating the convergence, interaction, and preservation of diverse cultural identities, fostering reciprocity, collective consciousness, and respect for diversity. Moreover, it serves as a platform for interrogating the prevailing patriarchal, racist, and xenophobic ideologies within an increasingly turbulent global landscape marked by escalating refugee migration flows.

For educators to effectively address the social, cultural, and national diversity inherent among refugee-immigrant adult students, a sustained and comprehensive program of education and training is imperative to cultivate the requisite “intercultural capacity.” This capacity enables educators to fulfill their pedagogical duties with proficiency and sensitivity toward culturally and economically vulnerable student cohorts.

Achieving the delivery of high-quality, targeted educational services necessitates a heightened degree of state sensitivity and investment, including substantial financial resources allocated toward refugee education. This encompasses the provision of the requisite logistical infrastructure, supervisory and supportive teaching aids, and enriched educational intervention programs tailored to the unique needs of adult refugee learners.

Significant reforms within both adult refugee education and the broader educational system are indispensable to enhance refugee education and facilitate their effective integration into the contemporary socioeconomic milieu.

Competent bodies must receive mandatory, sustainable, and comprehensive training programs in intercultural education and adult education. Without this training, it should not be possible to employ trainers in adult refugee-immigrant education structures.

Also, the Ministry of Education centrally must plan an educational curriculum which is the same and mandatory for all adult refugees. The program should be drawn up by the adult education structures themselves, be individual, and take the different learning rates of each refugee into account, targeting their educational needs, because they have different cultural, social, and academic backgrounds.

Training is imperative to foster the cultivation of the required “intercultural competence”. Embracing diversity and fostering inclusivity must become foundational principles guiding educational policy and practice.

Future national research endeavors should expand their scope to encompass a more expansive and representative sample of educators, along with a larger cohort of adult refugee learners. Additionally, forthcoming research should delve deeper into the factors influencing educators’ perspectives of interculturalism and the integration of refugees into the social and economic fabric of the host country.

Accordingly, future research can analyze intercultural education in other countries that receive refugee flows, such as Spain and Italy. Thus, a comparative analysis between the EU states and Greece should be possible, so that improvements can be implemented in the organization and operation of intercultural education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C.; methodology, E.C.; formal analysis, E.C. and R.M.-M.; investigation, E.C.; resources, R.M.-M. and E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.-M. and E.C.; writing—review and editing, R.M.-M.; supervision, R.M.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Governance of Migrant Integration in Greece. European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/country-governance/governance-migrant-integration-greece_en (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Kessidou, A. Intercultural education: An introduction. In Intercultural Education and Education. Training Guide; Papanaoum, Z., Ed.; Ministry of Education and Culture: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2008; pp. 21–36. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Voinea, M. The role of intercultural education in defining personal identity in the postmodern society. Redefining Community Intercult. Context 2012, 1, 236–239. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, L. The Impact of Postmodernism on 21st Century Higher Education. Master’s Theses, Hollins University, Roanoke, Virginia, 2021. Available online: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=malsfe (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Wilson, A.L.; Hayes, E. (Eds.) Handbook of Adult and Continuing Education; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2000; p. 735. [Google Scholar]

- Bećirović, S. The Role of Intercultural Education in Fostering Cross-Cultural Understanding. Epiphany 2012, 5, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency. Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees; Article 1, the Geneva Convention; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, A. Transitioning gender: Feminist engagement with international refugee law and policy 1950–2010. Refug. Surv. Q. 2010, 29, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Education: Domestication or liberation? Prospects 1972, 2, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaliki, E. Intercultural Education in Greece: The Case of Thirteen Primary Schools. Ph.D. Dissertation, Institute of Education, University of London, London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Essinger, H. Intercultural education in multi-ethnic societies. Bridge 1990, 52, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Byram, M.; Golubeva, I.; Hui, H.; Wagner, M. (Eds.) From Principles to Practice in Education for Intercultural Citizenship; 30; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moissidis, A.; Papadopoulou, D. The Social Integration of Immigrants in Greece, Work, Education, Identities; Athens Review: Athens, Greece, 2011. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Papachristos, K. Intercultural Education in the Greek School; Taksideftis: Athens, Greece, 2011. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Petracou, E.; Leivaditi, N.; Maris, G.; Margariti, M.; Tsitsaraki, P.; Ilias, A. Greece-Country Report: Legal and Policy Framework of Migration Governance; 2018; Available online: https://respondmigration.com/wp-blog/2018/8/1/comparative-report-legal-and-policy-framework-of-migration-governance-pclyw-ydmzj-bzdbn (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Gioka, P.E.K. Issues of Integration and Social Acceptance. Ph.D. Dissertation, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece, 2022. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Crush, J. Xenophobia Denialism and the Global Compact for Migration in South Africa. Rev. Int. Polit. Dév. 2022, Volume 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific Committee of the Ministry of Education Research and Religious. Refugee Education Project; Ministry of Education Research and Religious: Athens, Grece, 2017.

- Paleologou, N.; Evangelou, O. Intercultural Pedagogy: Educational, Didactic and Psychological Approaches; Pedio: Athens, Greece, 2003. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Pantelidou, S.; Craig, T. Culture shock and social support. Soc. Psychiat. Epidemiol. 2006, 41, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushner, K.; McClelland, A.; Safford, P. Human Diversity in Education: An Intercultural Approach; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou, G. Intercultural Teaching. The New Environment-Basic Principles; Ellinika Grammata: Athens, Greece, 2011. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D. Diversities in Education: Effective Ways to Reach All Learners; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gotovos, E.A. Education and Otherness. Issues of Intercultural Pedagogy; Metaichmio: Athens, Greece, 2002. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Wereszczyńska, K. Importance of and need for intercultural education according to students: Future teachers. Pol. J. Educ. Stud. 2018, 71, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouti, A.; Maligkoudi, C.; Gogonas, N. Language needs analysis of adult refugees and migrants through the COE-LIAM Toolkit: The context of language use in tailor-made L2 material design. Sel. Pap. ISTAL 2022, 24, 600–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR, The UN Refugee Agency. Greece. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/gr/en/29299-greek-language-courses-for-adults.html (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- GREEK FORUM OF MIGRANT. Available online: https://www.migrant.gr/cgi-bin/pages/index.pl?arlang=English&argenkat=&arcode=170123194122&type=article (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- INEDIVIM. (n.d.) Ίδρυμα Νεολαίας και Δια Βίου Μάθησης-ΙΝΕΔΙΒΙΜ (Foundation for Youth and Lifelong Learning-INEDIBIM). Available online: https://www.inedivim.gr/ (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- UNESCO. 4th Global Report on Adult Learning and Education: Leave No One Behind: Participation, Equity and Inclusion; UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning: Hamburg, Germany, 2019; 196p, Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000372274 (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Acharya, H.; Reddy, R.; Hussein, A.; Bagga, J.; Pettit, T. The effectiveness of applied learning: An empirical evaluation using role playing in the classroom. J. Res. Innov. Teach. Learn. 2019, 12, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEDIVIM. Information Leaflet. Available online: https://www.inedivim.gr/sites/default/files/2020-10-inedivim-enimerotiko-fylladio.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023). (In Greek).

- METAdrasi. Available online: https://metadrasi.org/%CE%B7-%CE%BC%CE%B5%CF%84%CE%B1%CE%B4%CF%81%CE%B1%CF%83%CE%B7/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- ACCMR. Available online: https://www.accmr.gr/en/about/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- European Commission. Law 4368/2016, Article 33 on Free Access to Health Care Services; Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs: Athens, Greece, 2016; Available online: https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/library-document/law-43682016-article-33-free-access-health-care-services_en#:~:text=The%20Greek%20Parliament%20has%20passed,on%20humanitarian%20grounds%20or%20for (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- European Commission. Law 4763/2020 (Government Gazette 254 A’) “National System of Vocational Education, Training and Lifelong Learning, Transposition into Greek law of Directive (EU) 2018/958 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 June 2018 on Proportionality Control before the Introduction of New Legislation (OJ L 173), Ratification of the Agreement between the Government of the Hellenic Republic and the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany on the Hellenic-German Youth Foundation and Other Provisions”. 2020. Available online: https://search.et.gr/en/fek/?fekId=598076 (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design Choosing among Five Approaches; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. Interviews: Learning the Art of Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, E.; Rao, A.H.; Summers, K.; Teeger, C. Interviews in the social sciences. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Validity and reliability. In Research Methods in Education; Cohen, L., Manion, L., Morrison, K., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 245–284. [Google Scholar]

- Wall Emerson, R. Convenience Sampling, Random Sampling, and Snowball Sampling: How Does Sampling Affect the Validity of Research? J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2015, 109, 64–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demazière, D.; Dubar, C. Analyser Les Entretiens Biographiques. L’exemple Des Récits D’insertion, 2nd ed.; Presses de l’Université Laval: Québec, QC, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Controversies in mixed methods research. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; SAGE: Newcastle, UK, 2011; pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, M.; Delahunt, B. Doing a Thematic Analysis: A Practical, Step-by-Step Guide for Learning and Teaching Scholars. AISHE J. 2017, 9, 3351. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, K.E.; Marx, D.M. Attitudes toward unauthorized immigrants, authorized immigrants, and refugees. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2013, 19, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafritsa, V.; Anagnou, E.; Fragoulis, I. Barriers of Adult Refugees’ Educators in Leros, Greece. Educ. Q. Rev. 2020, 3, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuali, T.T.; Bekerman, Z.; Bar Cendón, A.; Prieto Egido, M.; Tenreiro Rodríguez, V.; Serrat Roozen, I.; Centeno, C. Addressing Educational Needs of Teachers in the EU for Inclusive Education in a Context of Diversity; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakka, D. Greek teachers’ cross-cultural awareness and their views on classroom cultural diversity. Hell. J. Psychol. 2010, 7, 98–123. [Google Scholar]

- Friend, M.; Cook, L.; Hurley-C hamberlain, D.; Shamberger, C. Co-teaching: An illustration of the complexity of collaboration in special education. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 2010, 20, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez, K. What student teachers learn about multicultural education from their cooperating teachers? Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPherson, S. Ethno-cultural diversity education in Canada, the USA and India: The experience of the Tibetan diaspora. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2018, 48, 844–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miera, F. Not a One-way Road? Integration as a Concept and as a Policy. In European Multiculturalisms: Cultural, Religious and Ethnic Challenges; Triandafyllidou, A., Modood, T., Meer, N., Eds.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2022; pp. 192–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kärkkäinen, K. Learning, Teaching and Integration of Adult Migrants in Finland; Jyväskylä Studies in Education, Psychology and Social Research; University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2017; p. 316. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou, G. Integration and Education of Foreign Students in Primary School; Ellinika Grammata: Athens, Greece, 2000. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Magos, K. Coexistence in a multicultural society: Work plans in intercultural education. In Teaching and Learning in the Intercultural School; Govaris, C., Ed.; Gutenberg Publications: Athens, Greece, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). Terms of Reference: Review of the Australian Curriculum F–10. 2020. Available online: https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/general-capabilities/intercultural-understanding/ (accessed on 27 November 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).