Abstract

For many students, the start of a university course is a positive experience, as it is a challenge that involves academic commitment and the achievement of a university degree. However, for other students, access to university becomes a stressful experience that manifests itself in signs of anxiety. Previous studies have shown the influence of high levels of anxiety on the degree of academic engagement for good study performance, with positive or negative moderators such as psychological well-being or self-efficacy. The overall aim of this study is to analyse self-efficacy and psychological well-being as moderators between anxiety and academic engagement, as well as the relationships between the variables. In the present study, 751 first-year students of the Faculty of Education Sciences of the University of Granada (Spain), of whom 90.7% are women and 9.3% are men, all aged between 18 and 47 years old (M = 21.05, SD = 3.57), completed the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-Student questionnaires (UWES-S), Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS), State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and Psychological Well-being Scale. The correlations between scales were studied using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. To assess the moderating effect of self-efficacy and psychological well-being on the relationship between anxiety and academic engagement, structural equations were used with the maximum likelihood method. In relation to the analysis carried out, the findings show the importance of self-efficacy and psychological well-being as moderators between anxiety and academic engagement. Self-efficacy showed a moderating effect on the relationship between anxiety and academic engagement, so the interaction between anxiety and self-efficacy meant that in situations of high anxiety and high efficacy, academic engagement was virtually unaffected.

1. Introduction

European universities are concerned about their students’ emotional experiences, which affect both the students’ bodies and the institutions. Knowing the internal and external factors that can affect the mental health of students [1] may help predict their well-being and propose preventive or palliative measures for psychological distress. Accordingly, university counselling services are being used more frequently by students who manifest psychological discomfort [2]. Despite the measures taken to alleviate the psychological distress of students during COVID-19, negative effects on students with mental health instabilities still persist [2]. Several studies indicate that university institutions continue to design programmes to manage stress and anxiety and improve mental well-being [3,4] because of the persistence of these problems in students. The implementation of intervention programmes to improve psychological well-being is supported by some institutions as a preventive measure and to promote a healthy environment. Within these strategic axes of the university institutions, support services are offered, including lines of help through counselling and support services, such as psychological care services, the psychology and psychiatry office, and the health system, among others.

A crucial factor that influences university students’ decision to continue their education or drop out of school is engagement [5,6,7], which, in turn, may be affected by their psychological well-being, anxiety or perceived self-efficacy. Deepening their relationships and interdependence will, therefore, develop effective interventions during the transition phase from pre-university to university, during their time at the university, and during the post-university phase [1,7].

The relevance of the article presented, beyond demonstrating evidence that relates aspects such as self-efficacy, anxiety and psychological well-being with academic commitment, and the latter with dropout, gives us a clear idea of the situation experienced during the pandemic. Although the pandemic is in recession, and restrictions are not likely to occur again in the near future, it is possible that situations like this may recur in the not-too-distant future [8]. Therefore, it is of utmost importance for higher education institutions to know how students have experienced periods of confinement and to have evidence and objective data to propose specific actions to support students in these situations. We believe that the data and conclusions presented in this article are important for higher education institutions as a means of working on the definition and implementation of support actions to prevent student dropout due to reduced psychological well-being, self-efficacy, academic engagement and increased anxiety in situations of confinement or restricted mobility. Thus, knowing how students’ psychological well-being, anxiety and perceived self-efficacy influenced academic engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions could be an early predictor of successful or unsuccessful academic trajectories. This is even more relevant when universities indicate that they have had to increase the number of university counselling programmes and services due to situations of psychological distress that impact academic engagement, resulting, among other consequences, from COVID restrictions [9]. This event is preceded by a scenario in which university students claim that the blended learning system is more demanding and workload-intensive than the face-to-face system [10,11].

Engagement was initially described as a psychological construct consisting of a mental state based on occupational well-being [12]. Based on the study by Schaufelli et al. [13], the focus on engagement has shifted to academic environments [12,14] to highlight students’ positive or negative feelings that may influence their level of engagement in academic tasks [14,15]. Hughes et al. [16] proposed two similar dimensions—albeit with a different approach—behavioural engagement and emotional engagement.

For the purpose of our research, we will adopt a concept of engagement defined as a positive mental state related to the following three traits: vigour, which refers to energy and mental resistance during a task; dedication, which relates to motivation for and involvement in work during a task; and absorption, which is the state of concentration and immersion during a task [15,17,18,19,20].

Maslach et al. [21] indicate that engagement and burnout are opposing aspects of the same dimension because the former has a positive approach and the latter a negative. As indicated by Merhi [22], engagement is more related to factors such as perceived efficacy, social support, (intrinsic) motivation, good academic performance or increased persistence [13,15,23], whereas academic burnout is more associated with higher academic stress and lower personal strength indicators [12,24]. As indicated above, in this study, as a general objective, we will analyse the following factors related to engagement: self-efficacy, anxiety and psychological well-being, in addition to analysing self-efficacy and psychological well-being as moderators between anxiety and academic engagement.

- Factors between academic engagement and self-efficacy

Bandura [25] defines self-efficacy as “an individual’s belief in his or her capacity to execute behaviours necessary to produce specific performance attainments” (p. 3). An individual with high self-efficacy views problems as challenges to be faced; accordingly, their commitment is greater in terms of time, dedication and effort in tasks [25,26]. Thus, an individual’s well-being and achievements depend on a positive sense of self-efficacy to overcome the difficulties that may arise during the pursuit of goals [25]. Several studies show that self-efficacy is related to motivational behaviour and to the degree of academic engagement of the student when performing an academic task [27,28]. Thus, academic engagement is related to self-efficacy in that students rely on the development of their own competencies in order to complete academic tasks, and in that process, they develop various strategies, such as planning accurately, finding the positive aspects of the problem or seeking support and advice from people for instrumental and emotional purposes [29,30]. High self-efficacy is thus associated with less social anxiety and cognitive depression [31] and greater academic engagement in stressful situations [32]. From this point of view, we propose:

Hypothesis 1.

Self-efficacy will be positively related to academic engagement during periods of confinement.

Factors Between Academic Engagement and Anxiety

To assess self-efficacy, the learner reflects on his or her perceptions of ability, task difficulty, the effort required, previous experiences and degree of academic engagement. Anxiety is “a complex and variable model of behaviours, including objective, motor and physiological responses, as well as emotional and subjective-cognitive states of worry, fear and restlessness” [33]. According to this author, such behaviours occur in contexts that threaten self-esteem in terms of physical integrity because of possible future events or circumstances that may cause failure, and this response is an adaptive function. The multidimensional character of anxiety is expressed “by including different response components in its definition: affective, cognitive, motor, and physiological [components], the nature of the ‘stimulating situations’, and the individual characteristics of the subject” [33]. In tertiary education students, the prevalence of anxiety is approximately 35% [34,35]. More specifically, university students in the United States indicate that general state anxiety is the most notable health concern, reaching approximately 40% [36]. Considering that people with high levels of anxiety have a poor quality of life, universities may benefit from knowing about aspects of life that are related to a decrease in anxiety symptoms [4,36]. Therefore, in the university setting, early intervention is crucial [37,38,39].

Some studies indicate that anxiety can influence academic engagement, particularly during the examination period. Thus, anxiety is influenced by the appreciation of external and/or internal stimuli, according to beliefs, experiences, attributions, etc., which are perceived by the subject as threatening events [40,41]. In a confinement situation, students may experience high levels of anxiety that reduce learning effectiveness but do not directly on the student’s academic engagement. Thus, the student may have significant levels of anxiety but not necessarily low levels of academic engagement, as a high degree of academic engagement can regulate/control anxiety levels [32,39]. It is, therefore, the case that the degree of academic engagement could significantly intervene in the student’s involvement in academic tasks without anxiety, reducing engagement and thus undermining task performance [42]. We posed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

Anxiety could be positively related to academic engagement during periods of confinement.

- Factors between psychological well-being and self-efficacy

Lastly, psychological well-being is the development of capacities and personal growth of a subject based on the Aristotelian concept of happiness and the perfection of the subject as a function of individual capacities, among other notions [43,44]. This shows an individual’s handling of responses to the existential difficulties that arise in life [45]. Two types of well-being have been defined: subjective well-being and eudaimonic well-being. The former is characterised by satisfaction with life and its positive and negative outcomes [46]. The latter is based on the theory by Ryff (1989), who established that eudaimonic well-being depends on an individual’s cognitive evaluations based on a model consisting of the following six dimensions: self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life and personal growth [46]. Based on Bandura’s [25] social cognitive theory, we propose that the greater the pre-university success, psychological well-being and self-efficacy of the student, the higher the academic performance [47]. However, this academic success may not lead to greater academic engagement. The barriers and facilitators related to psychological well-being variables highlight the relevance of counteracting barriers and enhancing facilitators in order to increase levels of psychological well-being [48]. Considering that when students have negative perceptions of online learning, such that self-efficacy and psychological well-being decrease, it is not known how the latter two variables may influence academic engagement when students study online [49] due to restrictions such as COVID-19. It should be recalled that most universities had to improvise a plan to present an online teaching modality that was not free of implementation and adaptation problems [50,51,52].

Knowing that in university students who follow a face-to-face methodology, students who present high self-efficacy present high levels of academic engagement; however, the relationship between psychological well-being and academic engagement has not been studied as much, and even less with an online methodology [7,53]. For all these reasons, we put forward the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

Self-efficacy and psychological well-being as moderators between anxiety and academic engagement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Initially, the instrument was sent to 891 first-year students at the Faculty of Educational Sciences of the University of Granada (Spain) during the 2020/21 academic year. In total, 769 questionnaires were filled out, 18 of which were excluded because they were incomplete. The final sample included 751 first-year students, 90.7% of whom were women and 9.3% were men, aged between 18 and 47 years old (M = 21.05; SD = 3.57). Table 1 outlines the following demographic variables: employment status, with 85.6% students and 14.4% working students; degree, 37.2% primary education, 32.8% early childhood education, 15.8% social education, and 14.2% pedagogy undergraduate students.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic variables.

2.2. Instruments

Students’ academic engagement was evaluated using the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-Student (UWES-S) by Schaufeli et al. [54], whose Spanish version was adapted and validated by Belando et al. [55]. The instrument consists of 17 items evaluating the degree of engagement in studies using a Likert-type response scale ranging from 1, “strongly disagree”, to 5 “strongly agree”. The Spanish version of the instrument, the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS) [54], is made up of 15 items (using a Likert-type scale from 0 (never) to 6 (every day)). The items are distributed in three subscales: emotional exhaustion (EE) (5 items), cynicism (4 items), and academic effectiveness (AE) (6 items). The scores obtained in the questionnaire indicate the presence of academic burnout when they are high in the exhaustion and cynicism subscales and low in the academic effectiveness subscale.

The State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) instrument from Spielbergeret al. [56] is a subscale of trait anxiety (emotional state “in general” as stable propensity) used to measure the level of anxiety. The instrument contains 20 items whose responses correspond to a Likert-type scale from 0 to 3, where 0 is “almost never”, and 3 is “almost always”. The total scores are obtained by adding the values of the items (following the scores of the negative items). The total scores of the instrument range from 0 to 60, with higher scores being interpreted as a higher degree of anxiety.

The Spanish version of the Ryff Psychological Well-being Scale was applied [43]. The instrument has 29 items (e.g., “I have the feeling that over time I have developed a lot as a person”) distributed in six factors, which are self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, mastery of the environment, purpose in life and personal growth. The instrument is formatted with a Likert response scale comprising values between 1 “strongly disagree” and 6 “strongly agree”. The benchmark for a low BP presence is 90 points or less.

2.3. Procedures

Data were collected during the 2020/21 academic year among students of the Faculty of Educational Sciences of the University of Granada during the period of confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic in December 2020. The instruments, such as statistical treatment of the research data, were applied in accordance with the recommendations of the ethical standards of the University of Granada. The students were sent a link through a data collection platform to inform them that their participation would be voluntary and anonymous. The mean time to complete both questionnaires was 45 min.

2.4. Data Analysis

The variables were analysed using the mean, standard deviation, and absolute and relative frequencies. The reliability of the scales was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha. The correlations between scales were studied using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The relationship model used to evaluate the moderating effect of self-efficacy and psychological well-being in the relationship between anxiety and engagement was developed with structural equations using the maximum likelihood method. The model was evaluated using the following indices based on critical values suggested in the literature [57,58]: goodness of fit index (GFI) ≥ 0.95, adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) ≥ 0.95, comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ 0.95, normed fit index (NFI) ≥ 0.95, Tucker Lewis index (TLI) ≥ 0.95, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.05.

As can be seen in Table 2, none of the variables presents values of skewness greater than 3 or a kurtosis greater than 10, which indicates the non-existence of normality problems in the observed variables that will form part of the model [59]. On the other hand, the multivariate Mardia index value was 32.19, being less than 70 and indicating no deviation from multivariate normality [60]. To determine whether self-efficacy and well-being moderate the relationship between anxiety and engagement, a three-step hierarchical regression analysis was conducted for each moderator, following the procedure recommended by [61]. Moderation occurs when the interaction between the predictor variable and the moderator variable results in a significant regression coefficient and this coefficient is related to a significant increase in the variance explained.

Table 2.

Skew and kurtosis.

The results were statistically analysed using the statistical software IBM© AMOS Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 26.0, setting the level of significance at p < 0.05 in all tests.

3. Results

Table 2 outlines the means and standard deviations, Cronbach’s alpha reliability indices and the correlations between the scales. In terms of internal consistency, the alpha index values were above 0.80, indicating high reliability.

As can be seen in Table 3, all the scales correlated significantly with each other. In particular, anxiety correlated negatively with the other scales. Although weak, a significant negative correlation was observed between anxiety and self-efficacy (r = −0.158; p < 0.05); a strong negative correlation between anxiety and psychological well-being (r = −0.575; p < 0.001); and a significant moderate and negative correlation between anxiety and academic engagement (r = −0.296; p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Means (standard deviations), internal consistency, and correlations between variables.

On the other hand, significant positive correlations were found between self-efficacy and psychological well-being of moderate size (r = 0.296; p < 0.001); a significant positive correlation between self-efficacy and academic engagement (r = 0.343; p < 0.05) was also moderate. Finally, a significant direct positive and moderate correlation was found between psychological well-being and academic engagement (r = 0.259; p < 0.05). In general, if we analyse the means and standard deviations in the variables, we obtain average levels in all of them: anxiety (M = 17, 32; SD = 9.21); self-efficacy (M = 4.08; SD = 0.84); psychological well-being (M = 3.88; SD = 0.95) and academic commitment (M = 3.19; SD = 1.03).

- Self-efficacy and psychological well-being as moderators between anxiety and engagement

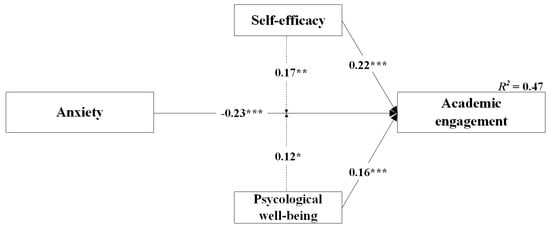

Figure 1 shows the result of the model used to evaluate the moderating effect of self-efficacy and well-being on the relationship between anxiety and engagement. Anxiety was significantly and negatively associated with engagement (β = −0.23, SE = 0.06, t = −3.83, p < 0.001); therefore, hypothesis 2 is not supported. However, the interaction between anxiety and self-efficacy showed a significant and positive effect (β = 0.17, SE = 0.06, t = 2.83, p = 0.005) on engagement. Similarly, the interaction between anxiety and psychological well-being showed a significant and positive effect (β = 0.12, SE = 0.05, t = 2.40, p = 0.017) on engagement. Lastly, both self-efficacy and psychological well-being were significantly and positively associated with engagement (self-efficacy: β = 0.22, SE = 0.06, t = 3.67, p < 0.001), supporting hypothesis 1, and psychological well-being: self-efficacy: β = 0.16, SE = 0.04, t = 4.00, p < 0.001). Therefore, the approach of scenario 3 is supported.

Figure 1.

Mediation model. Standardized coefficients were reported. * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001.

The model explained 47.3% (R2 = 0.473) of the total variance of engagement, and various model fit indices were adequate: GFI = 0.984; AGFI = 0.971; CFI = 0.986; NFI = 0.978; TLI = 0.972; RMSEA = 0.033.

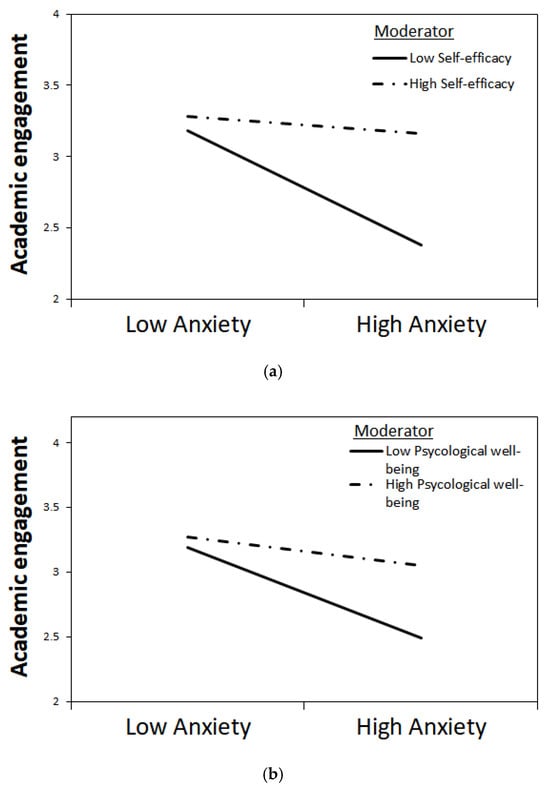

To further analyse the interactions, we examined the graphs of the means comparing the high- and low-anxiety groups (+1 SD and –1 SD). For self-efficacy as a moderator, Figure 2a shows the strong effect of anxiety on engagement. This effect is revealed by the higher levels of engagement in low anxiety and lower levels of high anxiety at both low and high levels of self-efficacy.

Figure 2.

Average engagement scores under anxiety and self-efficacy (a) and psychological well-being (b) conditions.

The strong effect of self-efficacy is also clear because the levels of engagement are higher in high self-efficacy compared to when in low self-efficacy. Interaction effects are observed in two ways: engagement is lower when anxiety and self-efficacy are low compared to when self-efficacy is high. Similarly, engagement is higher when anxiety and self-efficacy are high compared to when self-efficacy is low.

For psychological well-being as a moderator, Figure 2b shows the strong effect of anxiety on engagement. This effect is revealed by the higher levels of engagement in low anxiety and lower levels of high anxiety at both low and high levels of psychological well-being.

The strong effect of psychological well-being is also clear because the levels of engagement are higher in high than in low psychological well-being. Interaction effects are assessed in two ways: engagement is lower when anxiety and psychological well-being are low compared to when psychological well-being is high. Similarly, engagement is higher when anxiety and psychological well-being are high compared to when psychological well-being is low.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to analyse the relationship between anxiety, psychological well-being, self-efficacy and academic engagement; and, secondly, to analyse the possible moderating role of psychological well-being and self-efficacy in the relationship between anxiety and academic engagement. Given the relevance of the influence of anxiety on academic engagement for good study performance [62], it is essential to analyse the results of the positive or negative influences of psychological well-being and self-efficacy as regulators of the degree of academic engagement.

The results show a relationship between the variables that are significant in all cases and varies from weak to strong in magnitude. Anxiety correlates negatively with the other variables, weakly with self-efficacy, moderately with academic engagement and strongly with psychological well-being. That is, the higher the anxiety experienced by students, the lower their self-efficacy, psychological well-being and academic engagement. While psychological well-being and self-efficacy correlate positively and moderately with academic engagement, higher levels of well-being and self-efficacy are related to greater student engagement in their studies. These results reflect the relationship between anxiety, psychological well-being, self-efficacy and academic engagement—variables that are closely related and could be factors that explain students’ commitment to their studies. Previous work has already shown this negative relationship between anxiety and academic engagement, indicating that social anxiety problems are related to poorer indicators of engagement [63] and that this relationship might be mediated by other mental health problems [64]. In our research, anxiety was not significantly and negatively associated with academic engagement, so hypothesis 2 was not supported. The idea was put forward that in contexts such as confinement during COVID-19, students could have significant levels of anxiety but not inevitably low levels of academic engagement, on the assumption that high levels of academic engagement can control anxiety levels. Our results have not supported this assumption. Thus, in line with some research such as [65], it is confirmed that high anxiety lowers levels of academic engagement and can impair the development of academic tasks. However, students’ well-being and self-efficacy would positively influence their academic engagement by increasing or protecting it when there are adverse factors that can lead to university dropout [66,67].

In relation to the moderation analysis conducted, hypothesis 3 is confirmed. The findings show the importance of self-efficacy and psychological well-being as moderators between anxiety and academic engagement. In the present study, evidence was obtained of the beneficial effects of self-efficacy when moderating the relationship between anxiety and academic engagement. Previous studies have shown that levels of academic engagement decrease when students’ anxiety increases [63]. In addition, self-efficacy levels are higher when engagement levels are higher [64]. This paper also found that anxiety significantly and negatively influences academic engagement, providing further evidence that academic engagement may be reduced in situations that provoke feelings of helplessness in the student, leading to impaired psychosocial and physiological functioning [32,65,66]. However, self-efficacy showed a moderating effect on the relationship between anxiety and academic engagement, so the interaction between anxiety and self-efficacy meant that in situations of high anxiety and high efficacy, academic engagement was practically unaffected; it follows that a certain degree of anxiety may be adequate so that, in learning situations that require a degree of engagement, self-efficacy counteracts the negative effect that anxiety can have on engagement. Thus, these relationships may change according to the perception of the learning situation [5]. For example, a student with low self-efficacy who has to defend a paper in front of an academic tribunal will perceive physiological signs such as fatigue and distrust; in contrast, a student with high self-efficacy will perceive the same signs as normal. Our research suggests that if academic engagement is perceived as a positive stimulus, self-efficacy positively regulates student anxiety.

Another important finding in this study is that self-efficacy can be used as a possible predictor of academic engagement [67]. It is worth noting that, based on the results obtained, we can consider that if a student has high self-efficacy but this is not accompanied by academic engagement, the performance of an academic task may be reduced [68]. Along the same lines, research such as that of [20,65] confirms our results, considering that self-efficacy is based on the set of personal beliefs that students build and consolidate through experiences throughout their lives, influencing cognitive and affective responses in a learning context [20,69]. Therefore, a stressful situation such as a pandemic and confinement increases anxiety levels and lower perceived self-efficacy [32,65]. Thus, self-efficacy is related to academic engagement and associated with the ability to manage stressors that may impact academic performance [32,65]. The preliminary analysis presented here suggests that a student will perform better academically if, during academic activities, he or she manifests enjoyment and psychological well-being [70], even if high levels of anxiety are recorded. The moderation analysis suggests that psychological well-being as a moderator has an effect on the influence of anxiety on academic engagement.

Higher levels of academic engagement were observed when psychological well-being was higher compared to when psychological well-being was low. On the other hand, in a situation of high anxiety, high psychological well-being maintains levels of academic engagement, thus buffering the negative effect of anxiety on engagement. In an academic context, a student’s psychological well-being can increase beliefs in academic abilities and be reflected in increased academic engagement [68,71]. We observed that when anxiety and psychological well-being are high, academic engagement is higher. In contrast to previous studies, this level of engagement is reduced if psychological well-being is low, even when anxiety remains low. In our research, we highlight the relevance of psychological well-being as an indicator of positive functioning between anxiety and academic engagement [72]. Thus, in academic contexts where the university student shows signs of anxiety about the adequate development of studies, psychological well-being could be consolidated through academic commitment, academic permanence and a reduction in university dropout rates.

Despite the limitations outlined in the Limitations section, this study provides important evidence for preventing students from dropping out of university. Firstly, the clear negative influence of anxiety on academic engagement has been shown, with high levels of anxiety thus reducing engagement. But two variables have also been shown to protect academic commitment from anxiety, self-efficacy and psychological well-being. Institutions can work to ensure that teachers instil a sense of self-efficacy in their students. To this end, tutoring and continuous assessment make it possible to monitor students’ work in detail and to make them aware that their efforts result in changes and that they are effective in carrying out academic tasks. All this increases their persistence in achieving their academic goals. For future research, it would be useful to use instruments validated in the Spanish context.

On the other hand, it is important to take care of the mental health of the population at any age, but if we want to prevent students from dropping out of their studies, it is important to work toward the psychological well-being of university students so that the anxiety generated when facing a new stage, such as university studies, does not generate demotivation, poor academic and social integration or reduced expectations of achievement with the possibility of dropping out. Taking into consideration students’ educational paths, cooperative links between secondary school and university institutions should be encouraged, as motivation, self-confidence, academic commitment and exploration of subjects of real interest are consolidated during pre-university stages. This would enable students to plan realistically and to face their long-term academic development with vigour and dynamism [73]. It would be advisable for the university counselling teams to provide more information to students who are going to study at the university regarding the recommended entry profile and study plan [74,75].

Some specific initiatives that university institutions could carry out would be to offer free psycho-educational workshops and therapeutic groups programmed by the university’s own counselling team to work on self-esteem regulation, psychological well-being and anxiety management. Based on the results obtained, some interesting programmes that universities could offer are dog-assisted therapies to support cognitive-behavioural therapy for anxiety management and improvement in psychological well-being. Mindfulness-based programmes could also be successful when implementing these approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.G.P. and M.C.G.M.; Methodology, E.J.L.S. and M.K.G.; Software, E.J.L.S.; Validation, E.J.L.S. and M.K.G.; Formal Analysis, M.C.G.M.; Investigation, E.J.L.S. and M.K.G.; Resources, M.K.G.; Data Curation, J.G.P.; Writing—original draft preparation, E.J.L.S. and M.K.G.; Writing—review and editing, J.G.P. and M.C.G.M.; Visualisation, M.C.G.M.; Supervision, E.J.L.S.; Project Administration, E.J.L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Vice-Rectorat for Outreach and Heritage and Faculty of Education, University of Granada; the 2020 Programme of Activities of Outreach; Project: Stress-Less: “Take My Paws”; and Fostering Student Wellness with a Therapy Dog Program at the Faculty Library. The APC was funded by the Laboratory for Cognition, Health, Training and Interaction among Humans, Animals and Machines (SEJ-658) of the University of Granada (Spain).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee in Human Research of the University of Granada and followed 2212CEIH2021. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of the studies depicted in this paper will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bewick, B.; Koutsopoulou, G.; Miles, J.; Slaa, E.; Barkham, M. Changes in undergraduate students’ psychological well-being as they progress through university. Stud. High. Educ. 2010, 35, 633645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Houston, D. The perceived psychological benefits of third places for university students before and after COVID-19 lockdowns. Cities 2024, 153, 105299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijón, J.; Galván, M.C.; Khaled, M.; Lizarte, E.J. Levels of stress, anxiety, and depression in university students from Spain and Costa Rica during periods of confinement and virtual learning. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brites, R.; Brandão, T.; Hipólito, J.; Ros, A.; Nunes, O. Emotion regulation, resilience, and mental health: A mediation study with university students in the pandemic context. Psychol. Sch. 2024, 61, 304–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarte, E.J. Early Dropout in College Students: The Influence of Social Integration, Academic Effectiveness and Financial Stress. In Experiencias e Investigaciones en Contextos Educativos; Hinojo, F.J., Sadio, F.J., López, J.A., Romero, J.M., Eds.; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 519–531. ISBN 978-84-1377-171-7. [Google Scholar]

- Cerolini, S.; Zagaria, A.; Franchini, C.; Maniaci, V.G.; Fortunato, A.; Petrocchi, C.; Speranza, A.M.; Lombardo, C. Psychologica. Counseling among University Students Worldwide: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 1831–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galve-González, C.; Bernardo, A.B.; Núñez, J.C. Trayectorias académicas: El papel del compromiso como mediador en la decisión de abandono o permanencia universitaria. Rev. Psicodidáctica 2024, 29, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marani, M.; Katul, G.G.; Pan, W.K.; Parolari, A.J. Intensity and frequency of extreme novel epidemics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2105482118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kecojevic, A.; Basch, C.H.; Sullivan, M.; Davi, N.K. The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on mental health of undergraduate students in New Jersey, cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, J.M.; Almagro, J.; Fajardo, A.B. Percepción estudiantil sobre la educación online en tiempos de COVID-19: Universidad de Almería (España). Rev. Sci. 2021, 6, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedor, S.; Cervi, L.; Tusa, F.; Parola, A. Educación en tiempos de pandemia: Reflexiones de alumnos y profesores sobre la enseñanza virtual universitaria en España, Italia y Ecuador. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2020, 78, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, P.; Pérez, C. Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de compromiso académico, UWES-S (versión abreviada), en estudiantes de psicología. Rev. Educ. Cienc. Salud 2010, 7, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Van Rhenen, W. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portalanza, C.A.; Grueso, M.P.; Duque, E.J. Propiedades de la Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-S 9): Análisis exploratorio con estudiantes en Ecuador. Innovar 2017, 27, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazueta, A.G.A.; Herrera, G.O. Motivación escolar y desempeño académico en estudiantes de Enfermería en Culiacán Sinaloa México. RECIE FEC-UAS Rev. Educ. Cuid. Integral Enfermería Fac. Enfermería Culiacán 2024, 1, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J.N.; Luo, W.; Kwok, O.-M.; Loyd, L.K. Teacher-student support, effortful engagement, and achievement: A 3-year longitudinal study. J. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 100, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, P.R.; López, D.; Garcés, Y. Estudio sobre compromiso y expectativas de autoeficacia académica en estudiantes universitarios de grado. Educar 2021, 57, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. UWES-Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: Test Manual; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A. The measurement of burnout and engagement: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, J.R.; Sinval, J.; Almeida, L.S. Éxito académico, compromiso y autoeficacia de los estudiantes universitarios de primer año: Variables personales y desempeño del primer semestre. An. Psicol. 2024, 40, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merhi, R. Factores Psicológicos Predictores Del Bienestar y el éxito Académico en Estudiantes Universitarios. Un Abordaje Desde la Teoría de Demandas y Recursos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Facultad de Psicología:, Madrid, Spain, 2021. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14468/20933 (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casuso, M.J.; Moreno, N.; Labajos, M.T.; Montero, F.J. Características psicométricas de la versión española de la escala UWES-S en estudiantes universitarios de Fisioterapia. Fisioterapia 2017, 39, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez, S.; Gravini, M.; Moreta, R.; León, S.R. Influencia de la autoeficacia académica sobre la adaptación a la universidad: Rol mediador del agotamiento emocional académico y del engagement académico. Campus Virtuales 2023, 12, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumbrunn, S.; Broda, M.; Varier, D.; Conklin, S. Examining the multidimensional role of self-efficacy for writing on student writing self-regulation and grades in elementary and high school. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 90, 580–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çınar, E.; Karabacak, A. Psychological need satisfaction and academic stress in college students: Mediator role of grit and academic self-efficacy. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2023, 38, 131–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.; Ferradás, M. del M. Afrontamiento del estrés académico y autoeficacia en estudiantes universitarios: Un enfoque basado en perfiles. Rev. INFAD Psicol. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 1, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, D.; Godoy, J.F.; López, I.; Martínez, A.; Gutiérrez, S.; Vázquez, L. Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Autoeficacia para el Afrontamiento del Estrés (EAEAE). Psicothema 2008, 20, 155–165. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18206079 (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Singh, P.; Bussey, K. Peer victimization and psychological maladjustment: The mediating role of coping self-efficacy. J. Res. Adolesc. 2011, 21, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarte, E.J.; Botella, M.C.; Hernández, M.L.; Gijón, J. Stress-Less (Take my Paws): Proyecto para reducir el estrés ante los exámenes de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación de la Universidad de Granada. In Sociedad 5.0 ante la Pandemia: Investigación e Innovación Educativa; Díaz, I.A., Reche, M.P.C., García, S.A., Guerrero, A.J.M., Eds.; Octaedro: Granada, Spain, 2020; pp. 173–187. ISBN 978-84-18348-51-8. [Google Scholar]

- González, M.T. Aproximación al concepto de ansiedad en psicología: Su carácter complejo y multidimensional. Aula. Rev. Enseñanza Investig. Educ. 1993, 5, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, N.; Bilgel, N. The prevalence and socio-demographic correlations of depression, anxiety and stress among a group of university students. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008, 43, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakin Ozen, N.; Ercan, I.; Irgil, E.; Sigirli, D. Anxiety prevalence and affecting factors among university students. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2010, 22, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiter, R.; Nash, R.; McCrady, M.; Rhoades, D.; Linscomb, M.; Clarahan, M.; Sammut, S. The prevalenceandcorrelateso depression, anxiety, andstress in asampleofcollegestudents. J. Affect. 2015, 173, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BlackDeer, A.A.; Wolf, D.A.P.S.; Maguin, E.; Beeler-Stinn, S. Depression and anxiety among college students: Understanding the impact on grade average and differences in gender and ethnicity. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedillo, Y.E.; Davis, E.; Durham, L.; Kelly, T.; Kennedy, R.; Smith Jr, D.L.; Fernández, J.R. The effect of sociodemographic characteristics, academic factors, and individual health behaviors on psychological well-being among college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2024, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nola, M.; Guiot, C.; Damiani, S.; Brondino, N.; Milani, R.; Politi, P. Not a matter of quantity: Quality of relationships and personal interests predict university students’ resilience to anxiety during COVID-19. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 7875–7882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano, A.; Sprafkin, R.P.; Scaturo, D.J.; Lantinga, L.J.; Fiese, B.H.; Brand, F. Mental health screening in primary care: A comparison of 3 brief measures of psychological distress. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2001, 3, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotta, A.V.; Cortez, M.V.; Miranda, A.R. Insomnia is associated with worry, cognitive avoidance and low academic engagement in Argentinian university students during the COVID-19 social isolation. Psychol. Health Med. 2022, 27, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, D.; Rodríguez, R.; Blanco, A.; Moreno, B.; Gallardo, I.; Valle, C.; Van Dierendonck, D. Adaptación española de las Escalas de Bienestar Psicológico de Ryff. Psicothema 2006, 18, 572–577. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=72718337 (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Freire, C.; Ferradás, M.D.M.; Núñez, J.C.; Valle, A. Estructura factorial de las Escalas de Bienestar Psicológico de Ryff en estudiantes universitarios. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özmen, S.; Özkan, O.; Özer, Ö.; Yanardağ, M.Z. Investigation of COVID-19 fear, well-being and life satisfaction in Turkish society. Soc. Work Public Health 2021, 36, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, D.; Hernández, J.; Soler, M.J.; Cobo, R.; Espinosa, J.F. Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de bienestar PERMA para adolescentes: Alternativas para su medición. Retos 2021, 41, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, E.; Murray, A.V.; Duggan, M. Academic self-efficacy, student performance, and well-being in a first-year seminar. J. First-Year Exp. Stud. Transit. 2021, 33, 99–119. Available online: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/fyesit/fyesit/2021/00000033/00000001/art00005 (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Salanova, M.; Martínez, I.M.; Bresó, E.; Llorens, S.; Grau, R. Bienestar psicológico en estudiantes universitarios: Facilitadores y obstaculizadores del desempeño académico. An. Psicol. 2005, 21, 170–180. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/167/16721116.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Durón, M.F.; Pérez, M.A.; Chacón, E.R. Orientations to happiness and university students’ engagement during the COVID-19 Era: Evidence from six American countries. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 11, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.L.; Council, M.L. Distance learning in the era of COVID-19. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2021, 313, 389–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; You, X.; Wang, Z.; Kong, F. The link between mindfulness and psychological well-being among university students: The mediating role of social connectedness and self-esteem. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 11772–11781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasidou, E.; Raftopoulou, G.; Papadimitriou, A.; Stalikas, A. Self-compassion and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: A study of Greek college students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio Luquero, D. Bienestar Psicológico, Apoyo Social Percibido, cCompromiso Académico y Resiliencia en Estudiantes Universitarios en España. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Europea de Madrid, Facultad de Ciencias Biomédicas y de la Salud:, Madrid, Spain, 2021. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12880/2133 (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Martínez, I.M.; Pinto, A.M.; Salanova, M.; Bakker, A.B. Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2002, 33, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belando, N.; Ferriz, R.; Moreno, J.A. Propuesta de un modelo para la mejora personal y social a través de la promoción de la responsabilidad en la actividad físico-deportiva. Rev. Int. Cienc. Deporte 2012, 29, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.; Gorsuch, R.; Lushene, R. Cuestionario de Ansiedad Estado-Rasgo. Publicaciones de Psicología Aplicada; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2015; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M. EQS Structural Equations Program Manual; Multivariate Software Inc.: Encino, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. Int. J. Test. 2001, 1, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 1462523358. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, M.; Ruiz, M. Atenuación de la asimetría y de la curtosis de las puntuaciones observadas mediante transformaciones de variables: Incidencia sobre la estructura factorial. Psicológica 2008, 29, 205–227. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Berlin, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Salanova, M.; Schufeli, W.B.; Martínez, I.M.; Bresó, E. How obstacles and facilitators predict academic performance: The mediating role of study burnout and engagement. Anxiety Stress Coping Int. J. 2010, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, Q.; Zhuang, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Lu, Q.; Gao, F.; Zhao, M. The relationship between social anxiety and academic engagement among Chinese college students: A serial mediation model. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 311, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caraway, K.; Tucker, C.M.; Reinke, W.M.; Hall, C. Self-efficacy, goal orientation, and fear of failure as predictors of school engagement in high school students. Psychol. Sch. 2003, 40, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemany, I.; Rojas, G.; Granda, J.; Mingorance, Á.C. Influence of COVID-19 on the Perception of Academic Self-Efficacy, State Anxiety, and Trait Anxiety in College Students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 570017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouweneel, E.; Le Blanc, P.M.; Schaufeli, W.B. Flourishing students: A longitudinal study on positive emotions, personal resources, and study engagement. J. Posit. Psychol. 2011, 6, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Sanz, A.I.S.; Kuntze, J. Student engagement and performance: A weekly diary study on the role of openness. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriol, X.; Mendoza, M.; Covarrubias, C.G.; Molina, V.M. Emociones positivas, apoyo a la autonomía y rendimiento de estudiantes universitarios: El papel mediador del compromiso académico y la autoeficacia. Rev. Psicodidáctica 2017, 22, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criollo, M.; Romero, M.; Fontaines-Ruiz, T. Autoeficacia para el aprendizaje de la investigación en estudiantes universitarios. Psicol. Educ. 2017, 23, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mih, V.; Mih, C. Perceived Autonomy-Supportive Teaching, Academic Self-Perceptions and Engagement in Learning: Toward a Process Model of Academic Achievement. Cogn. Brain Behavior. Interdiscip. J. 2013, 17, 289–313. [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos, J.Y.; Encinas, F.C. Influencia del engagement académico en la lealtad de estudiantes de posgrado: Un abordaje a través de un modelo de ecuaciones estructurales. Estud. Gerenciales 2016, 32, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.T.; Fredricks, J.A. The reciprocal links between school engagement, youth problem behaviors, and school dropout during adolescence. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, P.R.; López, D.; Valladares, R.A. La influencia del engagement en las trayectorias formativas de los estudiantes de bachillerato. Estud. Sobre Educ. (ESE) 2021, 40, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarte, E.J.; Khaled, M.; Galván, M.C.; Gijón, J. Challenge-obstacle stressors and cyberloafing among higher vocational education students: The moderating role of smartphone addiction and Maladaptive. Front. Psychol 2024, 15, 1358634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizarte, E.J.; Gijón, J. El referente socioprofesional de la educación social: Tradiciones, funciones y competencias. In Innovación Docente e Investigación Educativa en la Sociedad del Conocimiento; Hinojo, F.J., Trujillo, F., Sola, J.M., Alonso, S., Eds.; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2023; pp. 543–558. ISBN 978-84-1324-589-8. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).