Abstract

Makerspaces have emerged as a popular supplement to formal K-16 STEM education, offering students opportunities to engage in hands-on, creative activities that integrate multiple disciplines. However, despite their potential to foster interdisciplinary learning, these spaces often reflect the techno-centric norms prevalent in STEM. As a result, makerspaces tend to be dominated by white, male, middle-class participants and focused on tech-centric practices, which may limit both who participates in these spaces and what types of activities they do there. To address calls to broaden student participation in makerspaces, we surveyed and interviewed undergraduate STEM students to understand how students’ perceptions of making and the makerspace itself influence their modes of participation. Using the lens of repertoires of practice, we identify which practices students believe to “count” in a STEM makerspace, finding that many students hold narrow, discipline-specific beliefs about making, which, for some students, were preventive of them visiting the facility. However, we also discover that students’ beliefs of making practices were malleable, indicating potential for shifting these views towards more inclusive, interdisciplinary beliefs. We conclude with recommendations for educators and makerspace administrators to broaden students’ conceptualizations of making practices and supporting such practices in STEM makerspaces.

1. Introduction

1.1. Making in STEM Education

Making as an educational activity has gained significant momentum in recent years, and with it, facilities designed to support making activities, known as makerspaces, have become increasingly prevalent throughout K-16 Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) education. These spaces, designed to encourage hands-on, interdisciplinary learning, are often seen as a means to enhance students’ engagement with STEM fields by integrating multiple disciplines via unique projects that are not typically incorporated into the traditional STEM curriculum. Significant resources have been invested into makerspaces in community spaces, K-12 schools, and higher education with the assumption that these environments can increase students’ interest, access, and persistence in STEM degree programs and career pathways (e.g., [1]). And indeed, researchers have found that makerspaces can be valuable places for strengthening students’ STEM interest, skills, and efficacies [2,3,4,5,6,7].

However, while makerspaces can potentially serve as inclusive environments that integrate knowledge from various STEM fields, there are ongoing concerns about their accessibility and the breadth of practices they support [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Some researchers argue that makerspaces tend to reflect dominant, techno-centric practices, often overlooking the interdisciplinary and more diverse activities that could engage a wider range of students. In particular, scholars have raised questions about the marginalization of non-dominant populations within these spaces, where traditional STEM norms may limit participation and the recognition of non-conventional STEM activities, such as crafting or community-based making [9].

These informal spaces, which function as a supplement to the formal STEM education curriculum, should provide students with the opportunity to draw upon their knowledge and experiences from multiple fields while exploring and solving authentic problems and ultimately deepening their understanding of STEM concepts. However, Vossoughi et al.’s [9] seminal essay on this topic questions what “counts” as making in STEM fields and who gets to decide; these authors argue that making is multidisciplinary in nature and caution against discounting this interdisciplinary nature in favor of the more dominant, engineering-oriented, techno-centric framing [9,13,14].

Guided by the theoretical lens of repertoires of practice [17], in this article, we investigate students’ perceptions of making practices in the context of STEM makerspaces, attempting to understand which practices they believe to “count” in STEM facilities, whether interdisciplinary practices are supported there, and how these beliefs influence their interest in engaging with the makerspace. Understanding students’ beliefs about these spaces is an essential step in designing making facilities that are truly multidisciplinary and inclusive.

1.2. STEM Makerspaces and STEM-Rich Making

A makerspace can be defined following Sheridan et al.’s [18] classification as an “informal site for creative production in art, science, and engineering where people of all ages blend digital and physical technologies to explore ideas, learn technical skills, and create new products” (p. 505). These interdisciplinary facilities are “physical location(s) that serve as a meeting space for a ‘maker community’ and house the community’s design and manufacturing equipment” [19]. In undergraduate STEM education, participation in a makerspace is typically not mandatory for students, unless required by a specific course assignment. Students often learn about the makerspace and its offerings via campus or department tours, university webpages, or inquiring about the space in person. These facilities typically have a few full-time staff members that train a team of student employees to operate all of the equipment in the space and train fellow students to do the same. Many undergraduate courses rely on makerspaces to support course projects, but students are also able to use the facilities for personal projects and interests.

These STEM makerspaces, however, tend to reflect a restrictive, techno-centric definition of making [9,13,14], prioritizing the practices recently rediscovered and recognized by dominant, gendered, white, middle-class cultural practices, rather than including materials or space for making that reflects “everyday practices that have been the historical domain of women” [9], like crafting and sewing.

Given makerspaces’ potential for fostering multidisciplinary practices, for this research, we adopt Calabrese Barton and Tan [11] definition of STEM-rich making, or “making projects and experiences that support makers in deepening and applying science and engineering knowledge and practice, in conjunction with other powerful forms of knowledge and practice” [11,20]. Calabrese Barton and Tan [11] definition of STEM-rich making is reflective of the interdisciplinary nature of making and allows space for practices like crafting and sewing, in addition to recognizing the “community insider knowledge and experience” that students bring into their making practices (p. 780). However, we hypothesize that STEM makerspaces may not often acknowledge or support these all of these practices, and that in reality, students will believe only certain practices “count” within the context of a STEM makerspace.

1.3. Benefits of Making Experiences

Research has shown that STEM-rich making can offer many benefits to students. Studies investigating the benefits of makerspace participation have reported student gains in “21st century skills” like collaboration [21], computational thinking [22], creativity [21,23,24,25,26], critical thinking [27,28], entrepreneurial thinking [23], ethical reasoning [29], leadership skills [30], problem-solving skills [27,31], and project planning and management skills [31,32]. Further, researchers have identified affective benefits to students’ appreciation of experiential learning [21], confidence [3], design self-efficacy [2,4,33], engagement [3,34], growth mindset [35], innovation orientation and innovation self-efficacy [2], motivation to learn [5,36], STEM enjoyment [27,37,38], STEM interest [31,39], sense of belonging [2,36], technological self-efficacy [2], and a “toolbox” of interpersonal and intrapersonal proficiencies [6].

Additionally, there is a wide body of literature examining factors that contribute to students’ choices to persist in STEM disciplines, and consistently, interdisciplinary skills like the ones listed above have been proven beneficial for persisting in STEM and having a successful career within or beyond STEM (see [40] for a review). By participating in a STEM makerspace, students are hypothetically given access to the opportunity to build these skills and efficacies; however, these benefits are only available to those students who are opting into making experiences by visiting an academic makerspace, and “there is little evidence that the maker movement has been broadly successful at involving a diverse audience, especially over a sustained period of time. The movement remains an adult, white, middle-class pursuit, led by those with the leisure time, technical knowledge, experience, and resources to make” [8].

While students can learn and develop skills relevant to professional STEM practices in makerspaces, when students try to access these opportunities, they are also faced with the marginalizing cultural norms prevalent in STEM disciplines [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16] and a “maker culture” that is unwelcoming to non-dominant students [9]; “those makerspaces that have reached beyond dominant populations are the exception, and not the norm … [and there is] little research documenting what is working, how or why” [9] (p. 213). To date, few studies have interrogated the factors that may motivate or deter students from participating in makerspace experiences, such as their beliefs about which disciplinary practices are welcomed by the established community within a STEM makerspace. Instead, research on STEM makerspaces relies on the voices and experiences of students who are already established within the facilities, greatly limiting our understanding of inclusivity in these spaces.

1.4. Aims of This Study

In this article, we examine the ways students conceptualize making practices in the context of STEM makerspaces, attempting to understand which practices they believe to “count” in STEM facilities, whether interdisciplinary practices are supported there, and how these beliefs influence their interest in engaging with makerspaces. Guided by calls to broaden participation in makerspaces, we investigate perceptions of a STEM makerspace amongst non-dominant undergraduate students who have limited experiences visiting the facility. Specifically, we ask the following questions:

- What practices do STEM students see as making?

- What practices do STEM students see as valid within a STEM makerspace?

Guided by the theoretical lens of repertoires of practice [17], this work is among the first to target students on the periphery of the modern making movement and sheds light on students’ perceptions of (inter)disciplinary making practices and STEM makerspaces before participating and during early experiences. Understanding these beliefs is a necessary first step toward (1) expanding and validating forms of making practices that may not currently valued in STEM spaces and (2) broadening the reach of the potential benefits of makerspace participation beyond white, male, middle-class spheres.

1.5. Positionality Statement

We recognize the importance of acknowledging our positionality as authors in relation to the social and political context of this study [41]. The following positionality statements disclose our identities, experiences, opportunities, journeys, and perspectives [42,43] to this study and within academic makerspaces.

Both authors are STEM education researchers with bachelor’s degrees in STEM. Author one’s bachelor’s and master’s degrees are in mechanical engineering, with her doctorate degree in STEM education, and author two has a master’s degree and doctorate degree in STEM education. As white women who have spent time in academic makerspaces and other STEM spaces, we have both experienced both privileging and marginalizing experiences but recognize the privilege of our identities that have benefited our paths to research and academia. We also recognize that our perspectives and positionality are influenced by our experience as citizens of the United States in academic makerspaces located in the United States. Our research on STEM makerspaces aims to promote the critical examination of these spaces and to identify and encourage equitable practices within makerspaces. As STEM education researchers, we value equity and inclusivity in a field that is historically more exclusionary than many other academic disciplines.

We are committed to increasing diversity in STEM, which is expressed in a variety of forms, including the social identities which have historically been the basis of discrimination in this field. We are committed to promoting equity by actively challenging dominant norms and critiquing oppressive systems; we believe that all students should have access to and opportunities for learning experiences like those in makerspaces. We are committed to deliberately working to ensure that STEM spaces are places where all are welcomed, differences are celebrated and respected, and all persons feel a sense of belonging and inclusion. Throughout this paper, we use the terms dominant/non-dominant in reference to social prestige and institutionalized privilege attributed to certain groups in their environment, recognizing the contexts that have and continue to marginalize certain learners.

2. Theoretical Lens

For this study, we rely on the theoretical lens of repertoires of practice [17]. Gutiérrez and Rogoff [17] articulate a cultural–historical approach to understanding learning experiences, defining three core concepts: (1) practices, or “the ways of engaging in activities stemming from observing and otherwise participating in cultural practices” (2) familiarity, “the familiarity of experience with local cultural practices”, and (3) dexterity, “determining which approach from a repertoire is appropriate under which circumstances” (p. 22). This perspective “aligns with constructivist and sociocultural notions that new learning always takes place within the context of previously learned knowledge, skills, symbol systems, and systems of meaning” [10]; in other words, the space and culture in which learning activities occur impacts how those learning activities manifest. Broadly speaking, the literature supports the concept that learning environments which are responsive to students’ diverse and culturally relevant skills, knowledge, and interests (i.e., repertoires of practice) have the potential to be both more effective and more equitable, in contexts including mathematics [44], science [45], and making [46,47].

Repertoires of Practice in Makerspaces

By adopting Calabrese Barton and Tan [11] definition of STEM-rich making, or “making projects and experiences that support makers in deepening and applying science and engineering knowledge and practice, in conjunction with other powerful forms of knowledge and practice” [11,20], we position making as an activity that can, and should, encompass a vast array of students’ repertoires of practice, including their past experiences in and knowledge of multiple STEM disciplines, as well as practices less commonly categorized as within the umbrella of STEM.

However, within any community or space, such as a STEM makerspace, there are certain repertoires of practice which are valued and seen as valid (i.e., practices that “count”) and others which are not. The modern making movement predominantly “remains an adult, white, middle-class pursuit” [8], and STEM makerspaces tend to reflect a restrictive, techno-centric definition of making [9,13,14], rather than including materials or space for making that reflects “everyday practices that have been the historical domain of women” [9], like crafting and sewing. We hypothesize that the technology-focused branding of the modern maker movement, the physical designs of STEM makerspaces, and the observable activities within those spaces might limit which repertoires of practice students believe to be valid and valuable, and thereby limit student participation; this may be especially true for non-dominant students, who face additional barriers to participation in these spaces [15].

Using the lens of repertoires of practice, Martin, Dixon [10] conducted a design-based research study aiming to support equitable engagement within their makerspace by acknowledging and building supports for high schoolers’ various repertoires of practice [17]. The authors centered their research around the question of “what counts as making and who has the authority to decide?” [10], articulating the conceptual restrictions placed on making in STEM contexts. Throughout their participatory research, the authors came to realize that as mentors, they were privileging larger projects over smaller ones (e.g., a robotics project over a laser cut keychain), and therefore, some students’ repertoires of practice “were tolerated but not sufficiently embraced or supported” (p. 41).

Similarly, the authors at first categorized one student’s helping practices as less than full participation in a making activity, but over time came to value not only the “material practices” of making, but also the “social ones” that this participant was exhibiting (p. 43). They found that students’ expressions of agency and resistance were important aspects of their making repertoires of practice and were key in helping the authors unpack their own assumptions about making, which at first minimized the importance of activities like exploration and smaller-scale projects. The authors’ self-reflection fostered a more equitable learning environment where “all students had the opportunity to share practices and to see them taken seriously and treated with respect” (p. 39). However, this ethnography only sampled students who were already participating in the makerspace via an elective maker class and thus had already found a place for themselves within the modern maker movement writ large. We build on this work in two ways: (1) we identify which repertoires of practice that students who choose not to participate in STEM makerspaces see as valuable in those spaces and (2) we analyze how the context of a STEM makerspace sets (and limits) the practices that are valued there.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Overview

To answer our research questions, we conducted semi-structured interviews with undergraduate STEM students. We distributed a recruitment survey through flyers in a central engineering building on a campus, which also houses the university’s STEM makerspace. A total of 151 students answered the survey, and from this group, 17 were selected for follow-up interviews to gain deeper insight into their experiences. During the interviews, we asked participants about their perceptions of the makerspace, their previous making experiences, and the divisions they observed within making practices. Then, using qualitative analysis guided by the lens of repertoires of practice [17], we explored students’ conceptualizations of making practices, familiarity, and dexterity.

3.2. Context of This Study

The makerspace in this study, The Invention Space (a pseudonym), is located within an engineering building on a college campus in the Southwestern United States. While the building primarily houses Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE) courses and lab spaces, it also includes various social and community spaces. These include the headquarters for engineering-specific student organizations (such as the Women in Engineering Program), engineering-specific student services (like the Engineering Study Abroad office), and the campus’s Engineering Library. The atrium of the building has ample seating available and serves as a communal meeting and study space for faculty, staff, and students of all engineering departments and students from other colleges.

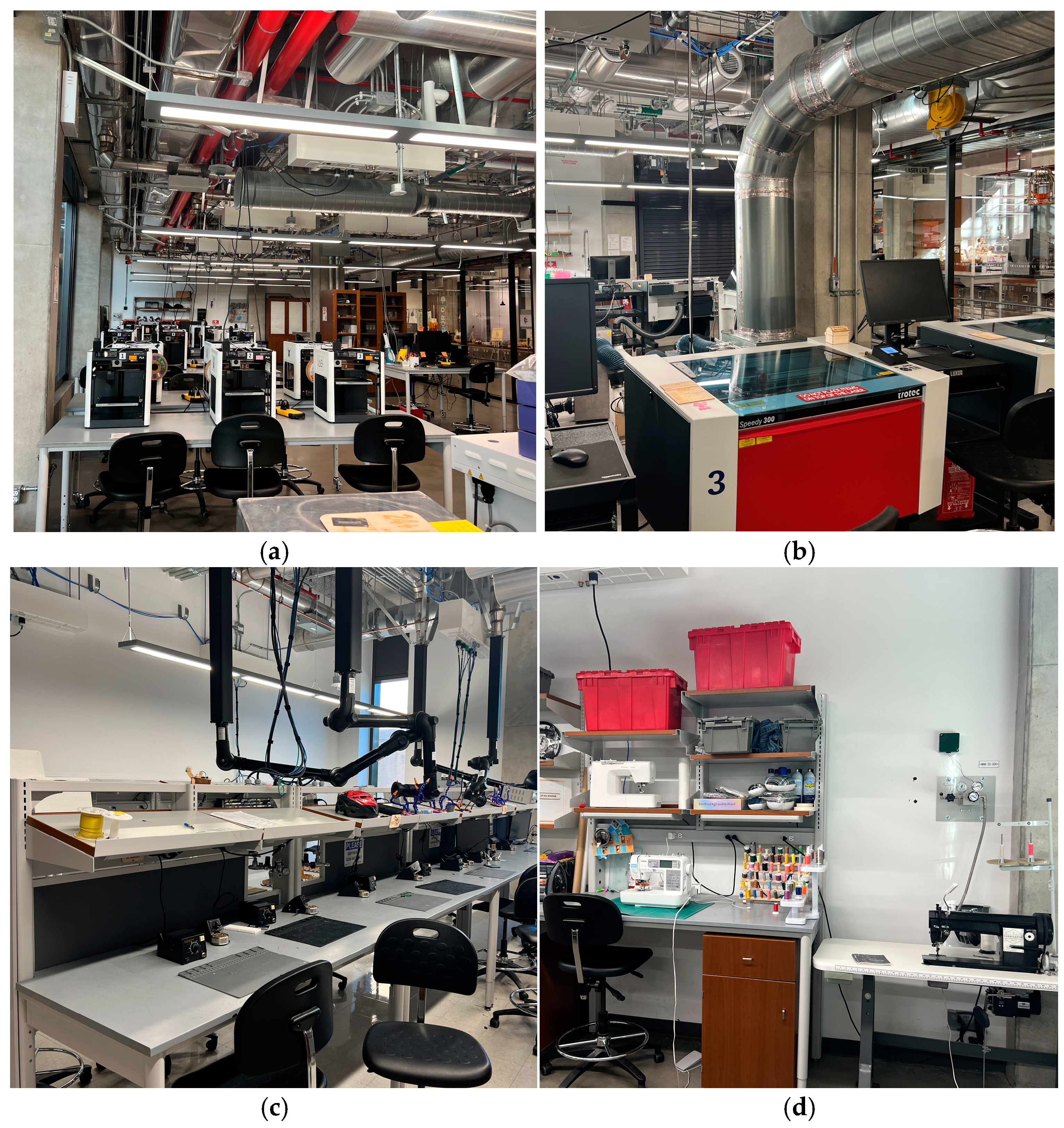

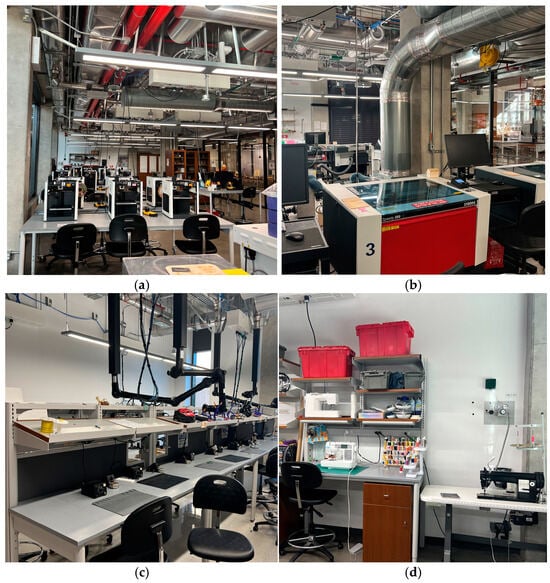

The building prominently features a 4-story-deep atrium with glass walls, allowing students to see the various spaces and resources housed within. The makerspace itself occupies the lower two stories of the atrium wall, spanning 30,000 square feet. Although large windows provide a view of the space, the entrance is hidden in hallways away from the atrium. This makerspace matches Hughes and Morrison’s [13] description of the design of STEM makerspaces, with its industrial design featuring exposed pipes, concrete floors, white tables, and prominently displayed technology and equipment. While the bulk of the makerspace is taken up by (a) 3D printers, (b) laser cutters, and (c) soldering stations, there is a small corner dedicated to a (d) sewing and embroidery machine (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Areas within The Invention Space.

The space is managed by four professional staff members and approximately 30 undergraduate part-time employees; these students provide the majority of the support available to their peers using the makerspace. While the space is open to all students, the majority of users are engineering majors [48]. Many STEM classes at this university incorporate assignments that require students to visit The Invention Space. These tasks often involve completing equipment training modules working on projects, such as 3D printing the school’s mascot. The space includes a variety of tools, equipment, and workspaces, including 3D printers, an embroidery machine, hand tools, laser cutters, sewing machines, soldering and circuitry equipment, and vinyl cutters. Students can book training sessions in person or via the makerspace’s webpage.

3.3. Data Collection

We distributed a recruitment survey through flyers posted throughout this building. The flyer included a QR code linking to the online survey and offered participants a chance to win a gift card. The survey featured both multiple-choice and open-ended questions about students’ perceptions of the makerspace, whether they had visited, their level of interest in the space, and their reasons for participating or not. Additionally, the survey gathered background and demographic information. All demographic questions allowed students to select options like ‘prefer not to answer,’ to select multiple options, or provide a self-description in an open field. The survey also included a question where students could indicate interest in participating in a paid, hour-long interview focused on making practices and makerspaces.

A total of 151 students completed the recruitment survey, and from these, 17 participants were chosen for follow-up interviews. Considering that the modern making movement predominantly “remains an adult, white, middle-class pursuit” [8], and that students from non-dominant backgrounds face barriers to engaging with STEM makerspaces [15], we intentionally selected interviewees from non-dominant backgrounds who had limited or no prior experience in the makerspace, rather than students who were established makerspace participants. These follow-up interviews allowed participants to share their perceptions of making, experiences making, views of the makerspace, and suggestions for improvements to the space (see Appendix A for the interview protocol). Prior to the interview, students received the interview questions via email and had the option to choose to interview in person or via Zoom 5.10.3. All interviews were recorded and transcribed via Zoom.

3.4. Research Participants

Table 1 provides an overview of the academic characteristics of our participants. The sample consists of 82% engineering majors and 18% non-engineering majors. The majority of students were enrolled in the ECE department.

Table 1.

Academic characteristics of sample.

Table 2 provides a demographic overview of our participants, including students’ gender identities, ethnic identities, racial identities, sexual identities, and identification with a disability or impairment.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of sample.

3.5. Analysis

Qualitative data analysis began at the outset of the study and continued throughout, following a process of “making sense of the data… [which] involves consolidating, reducing, and interpreting what people have said and what the researcher has seen and read—it is the process of making meaning” [49] (p. 178).

After each interview, the interviewer wrote an analytical memo summarizing the key points of the conversation. These memos served as “written records of analysis which document the analytical and methodological steps taken by the researcher” [50]. Once all interviews were completed, the interviewer revisited each audio recording and “pre-coded” the data, highlighting participant quotes that stood out as potentially important “codeable moments” [51] (p. 26). The interviewer then wrote a second analytic memo for each conversation, using these memos as a “code- and category-generating method” to gain a comprehensive understanding of participants’ experiences and to begin comparing their perspectives [51] (p. 50).

Next, the interviewer descriptively coded each interview transcript. Descriptive coding involves summarizing “ the basic topic of a passage of qualitative data” with a word or short phrase [51] (p. 76). This process allowed us to identify key concepts in the dataset, building a vocabulary of our data [51]. For instance, during this initial coding phase, we coded for any definitions of making practices students provided throughout our conversations. This step helped us gain a deeper sense of our participants’ experiences and informed the next phase of analysis.

In the next step, we applied “focused coding” to categorize the data based on our theoretical framework [17,51]. Focused coding involves identifying “the most frequent and significant initial codes to develop the most salient categories in the data corpus” [51] (p. 156). During this phase, the interviewer applied both deductive coding, using predefined codes from the repertoires of practice framework, and inductive coding, identifying emergent themes in the data. Focused coding enabled us to pinpoint participants’ specific conceptualizations of making practices, divisions within students’ thinking, and whether they felt certain practices were appropriate within the context of a STEM makerspace [17,51].

Within repertoires of practice, Gutiérrez and Rogoff [17] define three concepts: (1) practices, “the ways of engaging in activities”; (2) familiarity, “the familiarity of experience with local cultural practices”; and (3) dexterity, “determining which approach from a repertoire is appropriate under which circumstances” (p. 22). Organized by these concepts, Table 3 details the list of codes used while analyzing the interview data. These codes and memos included raw data, with the explicit intention of keeping the participants’ voices and meanings present in analytical outcomes.

Table 3.

Codes aligned to repertoires of practice framework.

From these codes, we categorized students based on their conceptualization of which practices count as making, and in which contexts. Most students had a narrow definition of making, meaning their definitions were highly restricted to specific practices, such as to creating something physical, for a class project, with a clear purpose or intent, and as an extension of the formal engineering design process; others saw making as something quite broad, meaning they position making as a part of human nature that is not specific to any discipline. We present six vignettes, organized from the narrowest to most expansive definitions of making; these vignettes are representative of each of the different perspectives of making expressed by students in our dataset.

4. Results

In this article, we examine the ways students conceptualize which practices count as making, and in which contexts. We highlight six vignettes representative of each of the range of perspectives on making that students articulated in our interviews. Each vignette is organized by each student’s practices, familiarity, and dexterity; Table 4 provides an overview of each student’s academic characteristics and views of making practices, their prior familiarity with making, and whether they view certain practices as appropriate for within the STEM makerspace, or their views of dexterity in STEM spaces.

Table 4.

Overview of participants’ repertoires of practice.

4.1. Annie: The Makerspace Is for “Engineering Making” and Class Projects

Practices—Annie is a white, heterosexual woman who identifies with a mental health disorder. She is a second-year Mechanical Engineering major who thinks about making in a direct relationship to engineering. In her view, “making is just creating something new, like combining multiple things to create something. And then, of course, that can be applied to like anything. But in engineering it means creating something that you made from a design. So making is kind of the next stage after the design process—design and manufacturing”. When she pictures engineering making, she thinks of manufacturing, modeling, and 3D printing.

Familiarity—In reflecting on her own experiences with making, Annie’s earliest associations with making practices are of “the Lincoln logs [she] had growing up where you can make a house, which is engineering based because it’s structural—you’re putting it together in a specific way and otherwise it won’t work”. She has also built a trebuchet in a high school physics course, and designed a floor plan in one of her undergrad courses, but does not consider the design practices as a making practice, because there “wasn’t a tangible, 3D result, we were just putting our ideas on paper”. Annie is in several student orgs that have hosted social events where they have engaged in more physical making practices by painting pottery and crocheting figures, but she sees those activities as “something different that you’re not gonna see in classes, it’s a creative outlet … it’s meant to be a break from engineering, not like engineering”.

Dexterity—This distinction is part of the reason she has never visited the makerspace on campus. Annie does not feel like she has a reason to go there, since she sees the makerspace as an academic area which she would only go to if she needs to make something for a class assignment. Because she equates the makerspace with engineering making for an academic purpose, and “going to The Invention Space would not be on like the top of my list of things that I would like to do outside of school hours because I don’t do a lot of personal engineering hobbies”.

4.2. Jerry: “There’s Making, and There’s Crafting”

Practices—Jerry is a white, asexual man and a third-year Computer Science and Math major who has never visited the makerspace, despite being very interested in visiting and having prior makerspace experiences. Jerry partitions practices into “crafting” and “making”. He thinks of making as “creating something that hasn’t been made before … I want to make it a broad definition, but in the context of makerspaces, it would have to be more physical things that are made with like general purpose tools”. He pictures 3D printing, woodworking, machining, and metalworking when he thinks of making and is only interested in the 3D printers housed in the STEM makerspace.

Familiarity—Jerry participated in the makerspace at his high school, where he designed and 3D printed physics toys and missing board game pieces for the games in the Computer Science Lab. Both in high school and college, he “somewhat” identifies as a maker. When asked if he saw any of his hobbies or of the clubs he was involved with as making practices, Jerry said he was a member of a student organization called “Crafters Circle, which is not engineering. They focus on sewing, knitting, painting, the more artsy-crafty making stuff. As for the technical making stuff, no”.

Dexterity—Jerry does not see a place for the practices he does in Crafters Circle within the STEM makerspace; he “wouldn’t expect to see sewing supplies in a maker space like this, but [he] would still count it as making”. He expects the makerspace to have “industrial creative machinery rather than low-tech machinery or low-tech tools” like sewing, which he sees as “artsy-craftsy type thing, rather than a technical thing”. He feels like “people’s expectations are that stuff belongs somewhere else, and not in a makerspace for engineers”. He thinks he would enjoy a makerspace that had arts and crafts supplies, but when he hears makerspace, he thinks “of the engineering type of makers first, before like the artsy-craftsy makers”. In talking about the differences between crafting and making, Jerry could not articulate anything that was fundamentally different between the two practices, besides his suggestion that crafts are lower-tech. He thinks there are “two side of making and one side has adopted the term making, like makerspace, and the other side is adopting the term crafting, or arts and crafts. And I feel like that’s where this like division comes from”. He sees no issue with the division between these practices.

4.3. Callie: “Traditional Making” Is “a STEM Endeavor” with a Physical End Product

Practices—Callie is a Latina, bisexual woman who identifies with a learning disability and is a fourth-year Electrical and Computer Engineering major who loves to bake and to make her own clothes from thrifted finds. Callie also partitions making practices along similar lines as Jerry, but her division relies on the intent and the end product of the practice. She thinks of making as a straightforward activity, where you have a vision of an end product and follow through on making it. She has visited The Invention Space once as part of a class requirement, and the activities she sees there are practices she calls “traditional making”, which involve a tangible result. For Callie, traditional making “constitutes building, so anything that involves something that belongs to a toolkit, like a hammer, a drill, that type of thing”. She associates making with physicality but, after some hesitation, decided to include software in her definition of making because “the end product… it exists, but it’s a little bit less tangible. It’s a software. It’s something that you know it still functions. But you can’t touch it”.

Familiarity—Callie is a member of the FreeTail Hackers on campus, which is a Computer Science organization. She thinks of her sewing and baking hobbies as making practices, and identifies as a maker because of baking—“which surprised [her]—[she] would have thought [it would be because of] coding or creating some type of coding project, but I guess because it’s a little bit less tangible”. She has also visited the makerspace in one of the Fine Arts buildings on campus and was drawn in by the “really cool sewing machine”, not knowing that the makerspace in the Electrical Engineering building also had sewing and embroidery machines.

Dexterity—She is frustrated by the divisions she sees in what counts as making, even in her own thoughts on what counts, reflecting that:

“Artwork feels like a different realm than making, which is, when I take a second to think about that, I don’t agree with myself on that. I wouldn’t like it to be this way, but I think to me, making feels like a STEM endeavor, whereas creating feels like a Liberal Arts endeavor. And I think that making feels very straightforward, I guess. You have this vision; you follow it through. But I think that creating… There are more steps along the process in terms of how do I feel about how this looks? And like what changes do I want to make. But I think that in reality those steps are, in the process of making, and the building, as well as in creating, which to me just feels more like an art word”.

Because of the types of activities she wants to do while making, she prefers the Fine Arts makerspace over The Invention Space, which she describes as “high risk”.

4.4. Cooper: Some Fields Are “More-Making Based” and More “Refined” than Others

Practices & Familiarity—Cooper is a white woman and a first-year Chemical Engineering student who grew up in a household with a “crazy craft room” where she became familiar with what she originally termed as “generic making… so like crafts”. She thinks of making as “taking something and transforming it into something notably different”, but at the beginning of our conversation, having reviewed the interview questions in advance, she remarked that she thought “this is the hardest question on that whole sheet”. She credits her interests in making as the main reason she is pursuing an engineering degree; while she sees making practices as a part of every field, she thinks of engineering as more making-based than other fields, “like a concentrated form of making”.

Throughout our interview, Cooper’s definition of making changed—at first making existed in a few categories, then a circle from more to less “refined”, and finally solidified as a model shaped like a witch’s hat—a cone that included all sorts of making (e.g., juggling, song composition, clay sculpture, developing relationships, and various engineering practices). Those most tangible forms of making were at the tip and those practices that were more abstract were towards the base. The brim of the hat represented the practices that she felt were on cusp of making practices, but still felt should be considered as a part of the conversation. She felt that STEM making practices would span a large range of the cone portion of the hat, but certainly not every form of making.

Dexterity—Cooper wrestled with which making practices she would want to see in a STEM makerspace, saying the following:

“I guess the question would be like, ‘Do you think The InventionSpace should incorporate broader definitions of making?’ In which case I would probably say no, because that’d be way too broad, because, like with the witch’s hat, you know, having from halfway up the hat to the top of the hat in a makerspace, that’s doable. But then, if you want to incorporate everything, that’s, that’s impossible”.

In making this distinction, Cooper was articulating that certain practices could never realistically become accepted within STEM makerspaces.

4.5. Rashad: “Well… Couldn’t You Call Everything Making?”

Practices—Rashad’s definition of making also evolved throughout our conversation. Rashad identifies as an Asian, heterosexual man and is a second-year Electrical and Computer Engineering student, who started the interview thinking of making as “just anything that involves tinkering or messing around with objects, or creating, anything that has some sort of practical purpose—usually practical. It doesn’t necessarily have to be practical, but it’s a broad term for all of engineering, just more hobbyist”. His initial reaction to what he pictures where he thinks about making was 3D printers and Arduinos, but he soon after expanded his definition beyond physical products only to include graphic design and software programming. When asked what would not count as making, he responded, “normally, when I think of making and makerspaces, I’m not really thinking about like fine arts, or regular art—that doesn’t necessarily fit the scope of it”.

Familiarity & Dexterity—Rashad is a big fan of watching educational YouTube videos that involve making practices, and in high school, he and a friend designed custom gaming keyboards together. While he typically associates making with hobbies, he does thinks of some of his Embedded Systems coursework, which involved a mix of software and hardware design, as making. Outside of class, he likes to cook and reflected that “maybe cooking is just fancy chemistry, right?” He was hesitant to call it making though, debating that “[he] called it more chemistry and chemistry is not technically… like its STEM but it’s not necessarily engineering. And [his] first gut instinct with making is engineering. But if your definition is like anything physical that science related, then yes, it is making”. Immediately after saying that, he balked at this line of thinking, calling it “elitist” and “exclusionary” towards non-engineers.

When speaking about people in his life who make, he bragged about a friend’s light-up, 3D-printed earring designs, which prompted him to rethink how he defines making practices, reflecting as follows:

“I think technically, they are the same thing, because if you’re printing something, that’s just like a physical version of art. And a sculpture is the same thing as a 3D printed thing, right? The only difference is that you do the work physically with the sculpture, and with 3D printing you’re CADing in software and putting it through a machine. So, you could include physical mediums of art somewhere in the definition of making. Well… couldn’t you call everything making?”

Rashad recognizes that students only do a certain subset of making practices in the STEM makerspace but feels “there’s no reason that that room or area cannot be used to make like stuff like [sculptures and earrings]”.

4.6. Sanya: Making Can Be Anything, but You Cannot Do Just Anything in the Makerspace

Practices—Sanya identifies as an Asian, bisexual woman and is a second-year Electrical and Computer Engineering major who uses the makerspace for her group project in a Humanitarian Engineering class—for her, making is simply creating something. Her “initial thought for making would be to build it, but you could always code it, or like, just present something”. She originally visited the makerspace as a requirement for a course and completed soldering training with her friend.

Familiarity—She first learned about making in her high school engineering class, but “before that I don’t think I ever thought of it as something I would do personally, I think because I thought it was a lot more elaborate of a thing, and I thought it would be a lot of work to make something”. She spoke enthusiastically about the train she designed for the engineering class, especially about the flowers she added to the top of the cars. Aside from that class, most of her making experiences are in The Invention Space through her Humanitarian Engineering project, but she “wouldn’t say I do it well enough to where I feel qualified to call myself a maker, but I do make things occasionally”.

Dexterity—She has never worked on a personal project in the space, because she feels she would be judged for doing so, perhaps because another one of her friends was confronted by multiple staff members about her methods for completing a project. In reflecting on this, Sanya feels “like sometimes, if you’re doing something not like a conventional way. It just seems like I’ll get judged, and I feel like part of that is because I’m a girl, and guys will just assume that I don’t know what I’m doing”. Sanya is an Asian student, but does not feel like her racial identity is as salient to her as her gender identity in the space because the people she sees working there are “not just a bunch of white guys. There’s a lot of different guys, but I feel like I don’t see as many girls of any racial identity”. In the makerspace, Sanya wishes she saw the following:

“people doing a bunch of things, instead of just seeing a bunch of guys cutting wood and gluing things together, or drilling things, or 3D printing things and just like bang-bang-banging on a woodblock. Like I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone like sewing, and I know they do that. Um. But if I saw that I feel like that would be cool”.

Personally, she does not feel comfortable trying out sewing in the makerspace, unless she could be with a friend of hers who has sewn there before.

5. Discussion

In their seminal, critical work which originated the call for questioning what “counts as making” (p. 214), Vossoughi, Hooper, and Escudé [9] critiqued the “branded, culturally normative definitions of making and caution[ed] against their uncritical adoption into the educational sphere” (p. 206). Following this call and building upon prior work aiming to expand dominant conceptions of what counts as making and to support inclusivity in STEM makerspaces [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], we sought to examine students’ conceptualizations of which practices count as making, and in which contexts—specifically from students on the outside of the STEM makerspaces.

We found evidence supporting the critiques of the modern making movement throughout our dataset; the normative definitions of making referenced by Vossoughi, Hooper, and Escude [10] are reflected in the narrow definitions of making held by STEM students; few students held beliefs as broad as Calabrese Barton and Tan [11] definition of STEM-rich making. Most students restricted making practices to creating something physical, for a class project, with a clear purpose or intent, and as an extension of the formal engineering design process. Students differentiate between practices they see as “more technical” and more “artsy craftsy”, positioning the latter as lesser than or not appropriate within the bounds of a STEM makerspace.

Our conversations with students show that the perception that certain practices are not valid or respected in the makerspace keeps many students from visiting, regardless of if they have prior experiences with either “traditional” or “non-traditional” forms of making—in other words, familiarity with making practices is not a determining factor for participation. However, throughout our conversations, most students expanded their definitions of making—some only slightly, and some to something much broader—indicating that these perceptions can be malleable via small interventions. This is promising for efforts to broaden student participation in makerspaces and for STEM makerspaces to meet their potential as interdisciplinary hubs of creativity and exploration.

Understanding these perceptions of making and STEM makerspaces is a necessary step in expanding and validating forms of making practices not currently valued in STEM spaces; “all students [should have] the opportunity to share practices and to see them taken seriously and treated with respect” [10], and doing so could transform makerspaces into truly multidisciplinary facilities. We organize the following discussion by students’ views of making practices, their prior familiarity with making, and whether they view certain practices as appropriate for within the STEM makerspace, or their dexterity. Then, we discuss implications of our findings.

5.1. Defining Making Practices

Other scholars have considered what it means to make, but the perceptions of students themselves have been largely absent in this conversation. Approaching this research, we adopted a researcher’s definition of “STEM-rich making”, or “making projects and experiences that support makers in deepening and applying science and engineering knowledge and practice, in conjunction with other powerful forms of knowledge and practice” [11,20]. The students that we interviewed largely defined making as only the first portion of this definition, rather than recognizing their own prior experiences and knowledge that should be valued during making practices [9,44]. Few students acknowledged the inherent value of self-expression through making or felt making was a broad, “fundamental human practice” (p. 76) [20].

The majority of students defined making in relation to engineering or STEM, and (at least initially) felt making meant creating something physical and academic from a formal design process. Few students included practices like crafting and sewing in their definitions of making, often describing these practices as “less tangible”, “less refined”, or “too artsy-craftsy”.

Several students explicitly partitioned making practices along disciplinary lines, including not only dividing “STEM making” and “Liberal Arts making”, but also drawing distinctions between more “traditional” or “technical” making in Mechanical, and Civil, Engineering, compared to practices like coding, etc., in other disciplines. Whether software and coding counted as making was often a sticking point during our conversations with students, as they wrestled with the dissonance between defining Computer Science activities as STEM, while simultaneously not initially seeing them as fitting within their physical definitions of STEM making; some evolved their definitions of making throughout our conversation to include this ‘STEM-enough’ form of making, while others doubled down on a more tangibility-oriented definition. Interestingly, when thinking about other tangible making practices that students did not associate with STEM, such as baking and sewing, few students changed their mind during the interview to include these practices as making.

A few students saw divisions in practices due to the intent of the activity, where so-called “engineering” making was a straightforward process with a clear product determined by consumer constraints, and more “creative” making was a freeform, hobbyist activity that relied more on aesthetic and personal preferences; in describing these differences, the creative practices were positioned as lesser than the academic practices. This hierarchy of project complexity that creates a division between more “academic” and “personal” pursuits may contribute to students’ sense that some of their prior making experiences do not really count as making, positioning the latter as lesser than or not appropriate within the bounds of a STEM makerspaces.

We note that all of the students we spoke with had pre-established definitions of which practices count as making before the interview occurred; this is perhaps an indication that these “culturally normative definitions of making” are something that students have learned from years of experience with and exposure to techno-centric STEM messaging [9]. However, while reflecting during our conversations, most students did shift their definitions of making—some only slightly, and some to something much more expansive—indicating that these perceptions can be malleable. For STEM makerspaces to meet their potential as interdisciplinary hubs of creativity and exploration, we argue that these perceptions must be altered.

5.2. Students’ Prior Familiarity with Making

Every student interviewed had prior making experiences from their childhoods, hobbies, coursework, experiences with friends and family members, extracurricular activities, etc., but several struggled to name any of the experiences when first prompted. Several students reflected that when they pictured making, they pictured the activities they see in the engineering makerspace, like 3D printing and woodworking. They then had trouble trying to decide if they would categorize their past experiences sewing, cooking, painting, crafting, making pottery, etc. as making, often remarking that while they did see how those things were making practices, they were not what came to mind when they pictured making. Further, they were only changing their mind about it now because the interviewer had explicitly asked about the distinction between these practices. This perception that certain practices are not validated in the makerspace kept many of our participants from visiting the makerspace, regardless of prior experiences with either “traditional” or “non-traditional” forms of making—in other words, familiarity with making practices was not a determining factor for participation.

5.3. Determining in Which Practices “Count” as Making in a STEM Makerspace

Overall, students’ responses showed divisions between what they conceptualized as making generally, and what they felt counted as making within the context of a STEM makerspace. What students are doing in the space (and which students are doing it) directly influenced students’ choices about whether to visit the makerspace and in which ways they were willing to participate there.

Some students equated the makerspace with “engineering making” for an academic purpose and, thus, did not intend to visit unless they were required to for a class. Most students did not view the types of making practices they partook in via personal hobbies, with family members, or in other student organizations as appropriate for or relevant to the engineering makerspace on campus; Callie, who sews and knew about the other makerspace on campus, preferred the Fine Arts makerspace because it was better aligned with the practices she enjoys. The division between which forms of making practices are accepted in which contexts frustrated Callie, Rashad, and Sanya, who all had more expansive definitions of making by the end of the interview and wanted to see a broader range of making practices happening in the STEM makerspace. Sanya specifically reflected on only seeing men in the space, and only seeing them working with the 3D printers and woodworking equipment, positioning the lack of other practices like sewing as a missed opportunity for the makerspace to increase participation there. How students participate in makerspaces, and which students are doing what in the facility, could shape students’ perceptions of what practices and which students count in STEM.

5.4. Implications

5.4.1. Avenues for Broadening Conceptualizations of Making

STEM students’ definitions of making often fall in line with the dominant, STEM-oriented, techno-centric framing of the modern making movement; further, it appears that this conceptualization of making is something students learn before ever encountering a university makerspace—it is likely developed through years of experience with and exposure to techno-centric STEM messaging. When incorporating either makerspace-based activities or in-class making practices in the formal curriculum, K-16 educators should encourage “more craft-oriented forms of making” [14], rather than dismissing them as “irrelevant to anything educational” in STEM [52]. Meaningful making does not need to include a large-scale, complicated project that spans an entire semester or school year (e.g., engineering senior design projects); instead, educators should offer more varied points of entry to making, as research indicates that students can thrive with more flexibility during making activities [10], which may in turn allow them to strengthen their STEM-rich making practices.

While most students defined making in relation to STEM or engineering, these conceptualizations appear to be malleable, both in our own data and in the prior literature [14]. For instance, Worsley and Bar developed an “Inclusive Making” course designed to encourage their students and readers to be “expansive in how they think about using making as a context for learning accessibility” [14] (p. 26); during this course, the students and authors visited a local crafting community, and later reflected that the organization “would not have fallen into the definition of makerspace that I walked in with on the first day of class”, but did by the end of the semester [14] (p. 23). Courses, class projects, or even field trips like these that showcase the true range of making practices show promise for quickly expanding students’ conceptualizations of making, and thereby broadening the making practices that occur in STEM makerspaces.

5.4.2. Avenues for Supporting More Forms of Making in STEM Makerspaces

Makerspace leaders can offer learners opportunities to engage with a wider variety of projects, such as the “everyday practices that have been the historical domain of women” [9] like crafting and sewing, and should place relevant materials and equipment prominently within the space. Showcasing and purposeful advertising of examples of students’ personal projects, which are sometimes seen as outside the scope of making, could counteract students’ feelings that personal, hobbyist, or more craft-oriented making practices are not validated within the STEM makerspace. Several students, including Sanya, spoke about the importance of seeing other students’ work and seeing other students using all of the available equipment, like the sewing machine, in making them feel comfortable trying those practices in the makerspace. Makerspace leaders could consider hosting a variety of events in the makerspace (rather than only a hack- or make-a-thon) to encourage engagement within the space (e.g., Newcomer’s Night, Laser Cut Your Favorite Literary Character Night, BYO T-Shirt Embroidery Hour, partnership events with student organizations that support nondominant students, etc.).

Finally, makerspace staff and fellow participants also directly influence their peers in the space. During students’ early experiences with the space, it is essential that makerspace administrators and staff members are careful and intentional in communicating the values of the space; we must all thoughtfully work to “change the narrative of who makers are, what making is, and who belongs in makerspaces” in order to “confront and transform—rather than reproduce—educational inequities” inherent in STEM makerspaces [7,52].

Some students directly faced marginalizing experiences in the makerspace that influenced their interest in further participation and mediated the forms in which they were willing to engage with other makerspace participants. Other students were simply aware of the types of making and types of makers that were accepted within the space without ever visiting. In order to broaden student participation in makerspaces, these spaces must be inclusive, interdisciplinary learning environments, or certain making practices will continue to be reified in these spaces. Makerspaces, or the departments that house them, should offer regular DEI professional development for staff to decrease bias amongst staff members; these conversations need to explain concepts like implicit bias and include examples of students in makerspaces who are approached or not trusted because of how they look. Additionally, makerspaces should regularly solicit feedback about student experiences from their participants (and especially from students who are opting not to participate) and offer opportunities for visitors to anonymously provide feedback about their experiences in the space to management.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we investigated perceptions of making amongst STEM undergraduate students using the lens of repertoires of practice [17]. We specifically interviewed students who had not ever visited a makerspace or had limited experiences there, as students on the periphery of STEM makerspaces have been largely absent from research about participation and inclusivity in these spaces.

We found evidence supporting the critiques of the modern making movement throughout our dataset. Most students have a narrow definition of making that is restricted to creating something physical, for a class project, with a clear purpose or intent, and as an extension of the formal engineering design process. Students differentiate between practices they see as “more technical” and more “artsy craftsy”, positioning the latter as lesser than or not appropriate within the bounds of a STEM makerspace. This perception that certain practices are not validated in the makerspace acts as a barrier towards participation for many students, regardless of if they have prior experiences with either “traditional” or “non-traditional” forms of making. Even if students do engage with the makerspace, they can face marginalizing experiences there that influence their interest in further participation and mediate the forms in which they are willing to engage with other makerspace participants. In order to validate all forms of making practices, we can offer more varied points of entry to making, actively work towards expanding students’ ideas about making, and be intentional about broadening student participation in these spaces.

Limitations and Future Work

We acknowledge several limitations to this study, including the opt-in recruitment process. Recruitment materials advertised a financial incentive for participation which may have skewed sample characteristics; distributing these materials in the engineering building that houses the makerspace likely led to the over-representation of engineering majors in our sample. Since the study specifically focused on students with little to no experience with the makerspace on campus, these data do not capture the experiences of non-dominant students who have successfully found a space for themselves in the STEM makerspace. While this somewhat limits the generalizability of these findings, research suggests that “makerspaces that have reached beyond dominant populations are the exception, and not the norm” [9] (p. 213), meaning this study is likely informative for the majority of these facilities. Additionally, this work was a part of a dissertation, and therefore, the first author was the sole interviewer and coder analyzing the data. However, interview memos, codes, and analyses were rigorously reviewed by members of the first author’s dissertation committee. Lastly, these findings are based on data from one site at one university, limiting the generalizability of the results to other university makerspaces.

Future work might explore how students’ majors influence their participation in a makerspace or beliefs about what counts as making. Given our findings that students’ beliefs are malleable, researchers and makerspace administrators might design interdisciplinary materials that expose students to a wider range of making practices than is currently highlighted in the space; understanding how large of an intervention is necessary to broaden student beliefs has the potential to expand student participation in these spaces. This study relied on interview data from 17 students; future work might explore students’ beliefs and participation patterns via a larger-scale survey and include analyses across different majors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E.A.; methodology, M.E.A.; software, M.E.A.; validation, M.E.A. and A.B.; formal analysis, M.E.A.; investigation, M.E.A.; resources, M.E.A.; data curation, M.E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.E.A.; writing—review and editing, M.E.A. and A.B.; visualization, M.E.A.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (#2044258) Opinions reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the granting agency.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas at Austin Project 2018020093, approved on 15 May 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Interview Protocol

- Can you start by telling me a bit about yourself?

- Can you define what “making” means?

- In what context did you first hear or learn about making?

- Are you interested in making?

- Can you think of a time when you’ve made something?

- Do you have any hobbies or participate in any student orgs here?

- Which ones?

- Do you think of any of those as “making”?

- Do you know anyone else who “makes”?

- Can you tell me again what you think of the makerspace?

- Have you visited the space since you took the survey?

- Do you have any interest in visiting the makerspace?

- If yes, why haven’t you visited?

- If no, why not?

- What do you think happens there?

- What do you think it would feel like to go into the makerspace for the first time?

- If you could design your ideal makerspace, what would you want to see in the space?

- Is there anything else about making or makerspaces that you think is missing from this conversation?

- Do you have anything else you’d like to add?

References

- Martin, L. The Promise of the Maker Movement for Education. J. Pre-Coll. Eng. Educ. Res. 2015, 5, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.E.; Borrego, M.; Boklage, A. Self-Efficacy and Belonging: The Impact of Makerspaces. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2021, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackley, S.; Sheffield, R.; Koul, R. Using a Makerspace approach to engage Indonesian primary students with STEM. Issues Educ. Res. 2018, 28, 18–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, E.C.; Talley, K.G.; Smith, S.F.; Nagel, R.L.; Linsey, J.S. Report on engineering design self-efficacy and demographics of makerspace participants across three universities. J. Mech. Des. 2020, 142, 102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Garcia, P.; Grau-Fernandez, T. Influence of maker-centred classroom on the students’ motivation towards science learning. Cypriot J. Educ. Sci. 2019, 14, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomko, M. Developing One’s “Toolbox of Design” Through the Lived Experiences of Women Students: Academic Makerspaces as Sites for Learning. Ph.D. Thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vossoughi, S.; Bevan, B. Making and Tinkering: A Review of the Literature; National Research Council Committee on Out-of-School Time STEM: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, A.C.; Tan, E.; Greenberg, D. The makerspace movement: Sites of possibilities for equitable opportunities to engage underrepresented youth in STEM. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2017, 119, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossoughi, S.; Hooper, P.K.; Escudé, M. Making Through the Lens of Culture and Power: Toward Transformative Visions for Educational Equity. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2016, 86, 206–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Dixon, C.; Betser, S. Iterative design toward equity: Youth repertoires of practice in a high school maker space. Equity Excell. Educ. 2018, 51, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese Barton, A.; Tan, E. A longitudinal study of equity-oriented STEM-rich making among youth from historically marginalized communities. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2018, 55, 761–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.; Calabrese Barton, A. Towards critical justice: Exploring intersectionality in community-based STEM-rich making with youth from non-dominant communities. Equity Excell. Educ. 2018, 51, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.M.; Morrison, L.J. Innovative learning spaces in the making. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, M.; Bar-El, D. Inclusive Making: Designing tools and experiences to promote accessibility and redefine making. Comput. Sci. Educ. 2020, 32, 155–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.E.; Boklage, A. Alleviating Barriers Facing Students on the Boundaries of STEM Makerspaces. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.E.; Boklage, A. Supporting Inclusivity in STEM Makerspaces Through Critical Theory: A Systematic Review. J. Eng. Educ. 2024, 113, 787–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, K.D.; Rogoff, B. Cultural ways of learning: Individual traits or repertoires of practice. Educ. Res. 2003, 32, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, K.; Halverson, E.R.; Litts, B.; Brahms, L.; Jacobs-Priebe, L.; Owens, T. Learning in the making: A comparative case study of three makerspaces. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2014, 84, 505–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczynski, V. Academic Maker Spaces and Engineering Design. In Proceedings of the 122nd ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–17 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bevan, B. The promise and the promises of making in science education. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2017, 53, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, P.M.; Nagel, J.K.; Lewis, E.J. Student learning outcomes from a pilot medical innovations course with nursing, engineering, and biology undergraduate students. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2017, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, M.; Pitkänen, K.; Laru, J.; Mäkitalo, K. Exploring potentials and challenges to develop twenty-first century skills and computational thinking in K-12 maker education. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, A.; Yoder, B.; Guerra, R.C.C.; Tsanov, R. University Makerspaces: Characteristics and Impact on Student Success in Engineering and Engineering Technology Education. In Proceedings of the 123rd Annual ASEE Conference & Exposition, Columbus, OH, USA, 26–29 June 2016; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, C. Problem-based science, a constructionist approach to science literacy in middle school. Int. J. Child-Comput. Interact. 2018, 16, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melián Díaz, D.; Saorín Perez, J.L.; Torre Cantero, J.L.d.l.; López Chao, V. Analysis of the factorial structure of graphic creativity of engineering students through digital manufacturing techniques. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 36, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Saorín, J.L.; Melian-Díaz, D.; Bonnet, A.; Carrera, C.C.; Meier, C.; De La Torre-Cantero, J. Makerspace teaching-learning environment to enhance creative competence in engineering students. Think. Ski. Creat. 2017, 23, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, M.; Qazi, M. BUILDERS: A Project-Based Learning Experience to Foster STEM Interest in Students from Underserved High Schools. J. STEM Educ. Innov. Res. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Geist, M.J.; Sanders, R.; Harris, K.; Arce-Trigatti, A.; Hitchcock-Cass, C. Clinical immersion: An approach for fostering cross-disciplinary communication and innovation in nursing and engineering students. Nurse Educ. 2019, 44, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.J.; Ludwig, P.M.; Nagel, J.; Ames, A. Student ethical reasoning confidence pre/post an innovative makerspace course: A survey of ethical reasoning. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 75, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskinen, J.; Kumpulainen, K.; Kajamaa, A.; Rajala, A. The emergence of leadership in students’ group interaction in a school-based makerspace. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 36, 1033–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walan, S. The dream performance–a case study of young girls’ development of interest in STEM and 21st century skills, when activities in a makerspace were combined with drama. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2021, 39, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeropoulos, N.; Walker, P.; Hale, C.; Hellgardt, K.; Macey, A.; Shah, U.; Maraj, M.P. Facilitating Independent Learning: Student Perspectives on the Value of Student-Led Maker Spaces in Engineering Education. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 36, 1220–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Vongkulluksn, V.W.; Matewos, A.M.; Sinatra, G.M.; Marsh, J.A. Motivational factors in makerspaces: A mixed methods study of elementary school students’ situational interest, self-efficacy, and achievement emotions. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2018, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.R.; Fischback, L.; Cain, R. A wearables-based approach to detect and identify momentary engagement in afterschool Makerspace programs. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 59, 101789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongkulluksn, V.W.; Matewos, A.M.; Sinatra, G.M. Growth mindset development in design-based makerspace: A longitudinal study. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 114, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadelson, L.; Villanueva, I.; Bouwma-Gearhart, J.; Youmans, K.; Lanci, S.; Lenhart, C. Knowledge in the making: What engineering students are learning in the makerspaces. In Proceedings of the Zone 1 Conference of the American Society for Engineering Education, Tampa, FL, USA, 16–19 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, P.-S.; Lee, E.M.; Ginting, S.; Smith, T.J.; Kraft, C. A case study exploring non-dominant youths’ attitudes toward science through making and scientific argumentation. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2019, 17, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kaplan, H.; Schlaf, R.; Tridas, E. Makecourse-Art: Design and Practice of a Flipped Engineering Makerspace. Int. J. Des. Learn. 2018, 9, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ramey, K.E.; Stevens, R. Interest development and learning in choice-based, in-school, making activities: The case of a 3D printer. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2019, 23, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Fang, M.; Shauman, K. STEM Education. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 41, 331–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, F. What literature review is not: Diversity, boundaries and recommendations. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2014, 23, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, B.C.; Simmons, D.R.; Lord, S.M. Dissolving the margins: LEANING INto an antiracist review process. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 110, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, C.; Reeping, D.; Ozkan, D.S. Positionality statements in engineering education research: A look at the hand that guides the methodological tools. Stud. Eng. Educ. 2021, 1, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, L.C.; Amanti, C.; Neff, D.; Gonzalez, N. Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Pract. 1992, 31, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese Barton, A. Teaching science with homeless children: Pedagogy, representation, and identity. J. Res. Sci. Teach. Off. J. Natl. Assoc. Res. Sci. Teach. 1998, 35, 379–394. [Google Scholar]

- Blikstein, P. Digital fabrication and “making” in education: The democratization of invention. In FabLabs: Of Machines, Makers, and Inventors; Walter-Herrmann, J., Buching, C., Eds.; Transcript Publishers: Bielefeld, Germany, 2013; pp. 203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Blikstein, P. Travels in Troy with Freire: Technology as an agent of emancipation. In Social Justice Education for Teachers; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 205–235. [Google Scholar]

- Josiam, M.; Patrick, A.D.; Andrews, M.E.; Borrego, M. Makerspace Participation: Which Students Return and Why? In Proceedings of the ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Tampa, FL, USA, 16–19 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Application in Education. Revised and in Expanded form “Case Study Research in Education”; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Timonen, V.; Foley, G.; Conlon, C. Challenges when using grounded theory: A pragmatic introduction to doing GT research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2018, 17, 1609406918758086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers Johnny Saldana; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tomko, M.; Aleman, M.W.; Newstetter, W.; Nagel, R.L.; Linsey, J. Participation pathways for women into university makerspaces. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 110, 700–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).