Unshackling Our Youth through Love and Mutual Recognition: Notes from an Undergraduate Class on School Discipline Inspired by Ta-Nehisi Coates and bell hooks

Abstract

| If the streets | |

| shackled my right leg, | |

| the schools | |

| shackled my left. | |

| Fail to comprehend the streets, | |

| and you gave up your body now. | |

| But fail to comprehend the schools | |

| and you gave up your body later. |

| As a classroom community our capacity to generate excitement is deeply affected by our interest in one another, |

| in hearing one another’s voices, |

| in recognizing one another’s presence. … Any radical pedagogy must insist |

| that everyone’s presence is acknowledged. … |

| The professor must genuinely value everyone’s presence. |

| There must be an ongoing recognition that everyone |

| influences the classroom dynamic, |

| that everyone contributes. |

1. The Multiple Layers of Mutual Recognition

2. Background to Our Project

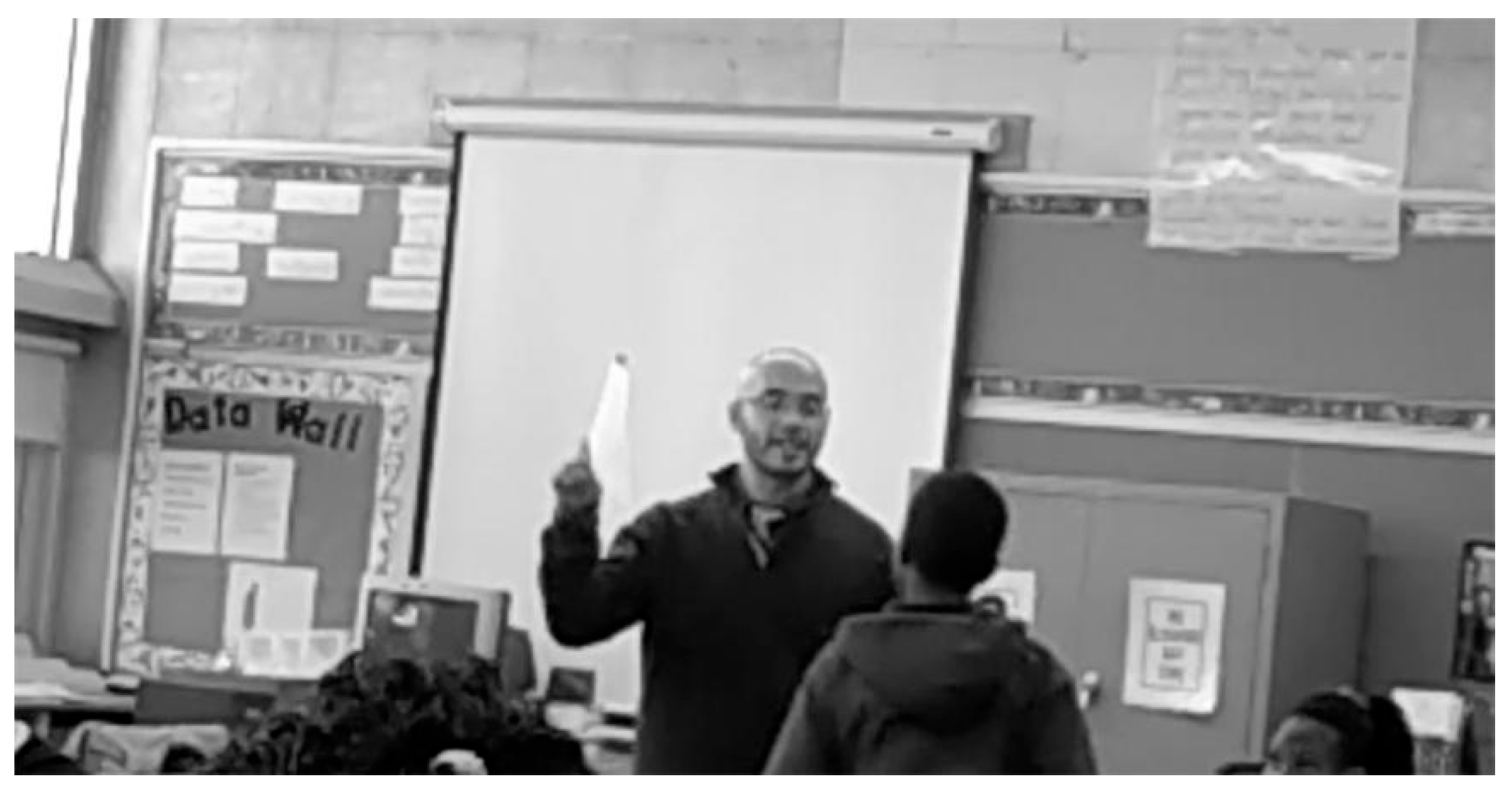

3. Introducing Tahjuan

4. The Class

“Good afternoon. To teachers, I was considered a bad student”.

“But where I come from, things happen in our lives where we are traumatized. So we come to school and we act in a certain way because we go through things.”

“Right at the end of my 6th grade year, my father got killed. … That was the one who was on me. When he died. I ran up the hill when that happened. His blood chunks was all on the car, his shoes, his teeth was in the tree. I was in 6th grade seeing all of that. So I was going through things.

When he was home, I had good grades. After he passed, there was nobody else I had to listen to. He was the only person that would keep me on track. … I was traumatized in a certain way and so I was acting a certain way in school.”

“When my dad died, I was traumatized, but Mr. C. [Mark] knew what I went through, and he let me get that out; he let me vent and let me express myself the way I wanted to. But I always knew we was in school, so when he said something I could relate to, I probably jumped in his face and said certain things to him. Other teachers would have took that as disrespect, or I’m misbehaving the way I was acting, my language–cursing and all that.”

“Once I got out of Mr. C’s class and I was acting the same way, the teacher didn’t understand me. I got to eighth grade, and I was acting like that, I was getting in trouble. I was getting suspended. 8th grade, yeah, I never went to school. The teacher wanted us to really be quiet like you could hear a pin drop. But I’m in eighth grade, you know what I’m saying? I should be happy to go to school.”

“He reminds me of me. I was homeless, my dad got deported, I didn’t have no food or nothing”.

“I ain’t going to lie, because I know, kinda, what he’s going through because I was the type of kid to get up and–I ain’t going to lie–I had a problem with always leaving the classroom because I have ADHD. You see I can’t stay still, always going in and out of the classroom like sometimes I get up and just peak my head out into the hallway. And the teacher said something, and I said something smart back and he like told me to go to the office. And I had stepped out and he was telling me in the hallway like you got to go to the office, you can’t come [back] into the room and what he does is grab me by the wrists and starts pulling me towards the office. I didn’t like that and I ended up cursing and told him to get off me and he didn’t listen and I said get off me again and at the end I was like get the fuck off me and after that I was about to start swinging because it’s a trigger. And I’m crying at this point.”

“Mr. C. knew what I went through. We had an understanding. He knew what I was trying to do. And I knew what he was trying to do. So I do what I do and then I get back and let him teach us.”

“I’m big on teachers having bonds with kids. That’s the one way you can get kids to listen to you. Then he’ll get the education he needs because he’ll want to listen to you”.

“He made a little comment about me, I made a little comment back, if you see, everybody just laughed, like it’s regular. Those classes could be long, so I used to feel like I got to do certain things, get a laugh, something just to get the minutes by because we be sitting down in that class for so long, but I feel glad that he was comfortable with me reacting like this because who knows…. because some teachers would take that as disrespect. You would have to be a cool teacher to let things like that by.”

“The only kids who could get away with things like that were the special ed kids, because it looked like something was wrong with them. You would see them in the hallway all the time, like not in line, while we all lined up. To be honest, I used to be trying to do things bad to get over there where they were at, because the teachers would let them do whatever, you know, because those minutes in the class could seem long as hell. Sitting there all day—you got to stand up, do certain things. But Mr. C. said, “there’s nothing wrong with you”. …I never liked school, to be honest. I still don’t like school. But Mr. C. could handle me. … The bond we had, made me want to go to school. He made me always want to come to school just by letting me be myself.”

“That’s the same like I used to act in school. But I got kicked out. I got suspended. Teachers didn’t like me.”

“I wasn’t in the regular class. I was in a BD [Behavioral Disability] class. I felt like they treated us different from every other class. They treat them a certain way, and when they get around us they tense up and act scared like we animals or something. And they brought regular kids to our class and told them, “You want to be bad, then go in here”. They made it seem like we were the worst class in the building. I used to feel, like why do you have to act like that. Like we–there’s nothing wrong with us, just because we got a label on our class don’t mean there’s something wrong with us.”

“Not only that. I’m a witness because I went to school with him actually. I was a witness. Sometimes they would even accompany you to the bathroom, walk with you.”

“Yeah. Like you would be monitored.”

“And I would continue to get up… They tend to say you’ll never be nothing in life, sometimes they can be the reason why you’ll never be nothing in life.”

“Some teacher said that to me. She just didn’t want to be bothered with me at all. …. No kid will just get up and be bad. …No kid just got that going on “today I’m going to be bad”. Sometimes if you sit down and talk and listen, we’ll break it down for you, but we don’t ever get asked, so what do we do? We come to school, throw things around, … doing things of that nature and you think that’s terrible, he’s bad, but we got things going on and there’s nobody to talk to.”

“My brother was in BD too, and mind you this kid, right now he goes to church, he’s singing for the church, he’s good, he’s not bad. It’s just me and him have a hitting problem. He was a little bit more worse than me, so in 7th and 8th grade he ended up being in BD class. I’m shocked I never got into it. I always had an aide with me, but I was never in a BD class.”

“That shit be cracking me up. What was I thinking about? I don’t be thinking, I just be talking. I be cursing and stuff.”

“So, Tahjuan, you lifted up this idea of language. You bring this up all the time when we talk about this clip and you bring it up in the next clip too. Why?”

“Because, you know, we joking, playing and all that, but I don’t know, when I be watching it I be like, damn, I be using foul language and we got to show this to people, even though you trying to get them to understand, I be like, damn, I don’t like when I be cursing and doing all of that in class like that. I don’t know why. I knew exactly what I meant and what I was talking about with that situation, but when I be expressing myself sometimes, I just curse, and then I look and I don’t know why I was cursing. Even though it was nothing bad, but it’s good to be code switching. You know I’m in school and that language is not for school, you know what I’m saying.”

“You got everybody to laugh. Don’t you think you enjoyed that?”

“I did, I did. But I’m older now. I was 12 then, I’m 25 now. That’s a fact.”

“To be honest, I don’t think teachers should make cursing a big thing because sometimes that’s just how people express themselves. …What bothers me is when a teacher gets mad when a kid curses in class and they’ll get extremely in trouble for it. Ok, I’ll apologize. But sometimes that’s just how they express themselves. Like me, I talk, and I use curse words in my talking but I’m not disrespecting nobody. I think it should only be a problem if you’re using it disrespectfully.”

“As long as it’s not disrespectful, it’s not like a big problem. I’d say, … it’s the teacher’s job to try to get them to decrease how much they curse, instead of like bashing them.”

“They [the cops] don’t like it when you know your rights. I’m talking from experience. You start talking about your rights to them, they don’t like that. Because they expect us to not know. You know things like that, that gets them pissed off even more. Trust me.”

“When I watch that video now, I be like, damn, I’m like 12. I’m 25 now and that stuff’s still happening, you feel me? But we live like it’s normal. I’m acting a certain way toward them [the police] because they made me feel like, ya suppose to be here to serve and protect me, but ya make me feel like I gotta protect myself from ya now.”

“I feel I can open up to Mr. C. I know he ain’t going to be looking at me different. He can feel my pain, what I’m going through. I’ve been going through this for years. It’s what makes me who I am now. A lot of teachers don’t understand because most–they from Westville, they from Plainfield [mostly white affluent cities] —they can’t relate to what we’re going through. They just see a bad-ass kid: he’s trouble, I don’t want him in my class, I can’t handle him.”

“We just traumatized. A lot of things happen to us, our families, we see a lot, we just react differently. Holding it in will hurt you. Mr. C. knew that. The next teacher didn’t understand that. That is why I had problems in 8th grade a lot, getting suspended for things that you see I be doing. After the next year, I was getting suspended for the same things.”

As a classroom community, our capacity to generate excitement is deeply affected by our interest in one another, in hearing one another’s voices, in recognizing one another’s presence.

“I had one teacher, her name was Miss D, she used to do the same thing [Mark does], pull me to the side, talk to me. I had the same exact bond, every time everybody used to go to her, “how do you handle him,” you got to talk to him, let him be. And she actually start helping me get my grades up. She’s the reason I got out of BD. I used to feel like everybody who was not in BD was better than me.”

5. The Shackles of the Street and the Possibilities of Mutual Recognition

“A black boy is always going to be forced to grow up. That’s why, a lot of times, you see young men having kids at a young age because growing up as a black man, your life expectancy is short so you trying to do everything in a grown man’s life at one time. In some situations, you’re forced to be a man.”

“Yeah, the streets, one foot in and one foot out, It’ll always be like that in the streets. Even though you trying to not be in the streets and always things that happen to a family member or friend, a death or something that have you go back–even though you know you don’t get nothing out of it–something happen to one of your bros or something like that, you know two wrongs don’t make a right but in your mind your angry and filled up all the time you feel like you have to go and do whatever just to–because of what happened to your bro, and that’s why when a person try not to be in the streets then something happens to somebody that they love or was close to so much, then they feel like they just gotta jump back in the streets. I don’t know, that’s just how it be.”

“What they getting at, it’s also the way the streets is set up. Alright, you’re going to school, you’re learning math, all of that, in the streets, counting money. With getting money itself, there’s a lot of money inside the streets. Making money is like a drug. Some people look at money as way more important than learning in school. You know what I’m saying. It depends. Its kids that’s tied to the streets that ain’t never did nothing a day in their life that’s just related to the specific people that’s in the streets, so then they got to watch out for they selves and everybody around them. So it’s a hard thing.”

“You know I’ve been doing this since I was 12. Teaching classes in how to deal with kids like me. When I be breaking it to the bros about things like this, they use to me a certain way, they laugh … They don’t know this side of me, “You what? You gonna do what? Get out of here. No you’re not”. So I’m going to bring you with me to show you we could be street and hood. So I’m just trying to enlighten the bros, … I’m just showing there are different things we do than just be in the hood. I’m in the hood doing street stuff too, but I know how to switch up. This is why he’s here [indicating the friend he brought with him]. My other brother, K, I brought him with me one time too. I want to show them different things cause like I’m somebody that really matters, so I be feeling like if they see me doing things they can feel like they can do this. If I can do it, you can do it. Because a lot of the bros in my hood, all they know is the hood. I just brought bro to show him different things that I’m capable of doing other than just being in the hood. I hope he’s inspired in the right way, you know what I’m saying. Because he a little different. He a little hot head. So, to break him out it, and for him to like it, I feel I’m doing something, you feel what I’m saying. … I love my little brother…. This ain’t my blood, you know, …This not my mother’s son, This ain’t nobody, but I love him…This is my little brother. I just want to show him other things.”

6. This Ain’t Nobody, but I Love Him and Want to Show Him Other Things

“Tahjuan you lifted this up–your story is the same as his story [M]… and the same as your story [Sophia] even though you were in another building, and the same as yours in a school in another place in the city [an undergraduate student]. And we had a young man from Mobile Alabama who was here, who said, yeah, this is exactly how my high school was also. There is something that is happening that makes this true not just in North Newark, but in all of Newark, across New Jersey, and across the country.”

“There are more kids that are like me. I’m not the only one. There are a lot of them like me. My school was filled by kids like me.”

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coates, T.-N. Between the World and Me; Spiegel & Grau: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. In Culture: Critical Concepts in Sociology; Jenks, C., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Volume 3, p. 312. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. The Culture of Education; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Discipline & Punish, 2nd ed.; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- hooks, b. Teaching to Transgress; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, R. Invisible Man; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Anyon, J. Social class and school knowledge. Curric. Inq. 1981, 11, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellner, G. The problem is education not “special education”. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2015, 10, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiles, A.J.; Kozleski, E.B.; Trent, S.C.; Osher, D.; Ortiz, A. Justifying and explaining disproportionality, 1968–2008: A critique of underlying views of culture. Except. Child. 2010, 76, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkwae, A. Schooling the police: Race, disability, and the conduct of school resource officers. Mich. J. Race Law 2015, 21, 147–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C. Stereotype threat and African-American student achievement. In Young, Gifted and Black; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, J. A Talk to Teachers. 1963. Available online: https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/baldwin-talk-to-teachers (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Dudley-Marling, C.; Burns, M.B. Two perspectives on inclusion in the United states. Glob. Educ. Rev. 2014, 1, 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, A.A. Bad Boys, Public Schools in the Making of Black Masculinity, 1st ed.; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bos, A.E.R.; Pryor, J.B.; Reeder, G.D.; Stutterheim, S.E. Stigma: Advances in theory and research. Basic Appl. Soc. Pscyhology 2013, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunch, G.; Valeo, A. Student attitudes toward peers with disabilities in inclusive and special education schools. Disabil. Soc. 2004, 19, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bois, W.E.B. The Souls of Black Folk, 1st ed.; A. C. McClurg: Chicago, FL, USA, 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin, M. Rabelais and His World; Iswolsky, H., Translator; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fellner, G.; Comesañas, M.; Ferrell, T. Unshackling Our Youth through Love and Mutual Recognition: Notes from an Undergraduate Class on School Discipline Inspired by Ta-Nehisi Coates and bell hooks. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030269

Fellner G, Comesañas M, Ferrell T. Unshackling Our Youth through Love and Mutual Recognition: Notes from an Undergraduate Class on School Discipline Inspired by Ta-Nehisi Coates and bell hooks. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(3):269. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030269

Chicago/Turabian StyleFellner, Gene, Mark Comesañas, and Tahjuan Ferrell. 2024. "Unshackling Our Youth through Love and Mutual Recognition: Notes from an Undergraduate Class on School Discipline Inspired by Ta-Nehisi Coates and bell hooks" Education Sciences 14, no. 3: 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030269

APA StyleFellner, G., Comesañas, M., & Ferrell, T. (2024). Unshackling Our Youth through Love and Mutual Recognition: Notes from an Undergraduate Class on School Discipline Inspired by Ta-Nehisi Coates and bell hooks. Education Sciences, 14(3), 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14030269