1. Introduction

The complexity of providing music teachers with adequate tools and knowledge to develop pupils’ musical creativity has been discussed in various studies [

1,

2]. A challenge resides in developing a conceptual understanding of this “umbrella term” [

3] and in identifying the specific pedagogical knowledge needed to implement and develop musical creativity in the classroom.

This topic is particularly relevant for teacher training in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, where creativity is not systematically implemented in music teacher education. This situation is somewhat surprising, given that the curriculum for general music education in compulsory schooling explicitly mentions integrating improvisation and other forms of musical creativity like inventing or composing (Plan d’études romand, axis 1, [

4]). Previous research has already identified this problem in the context of primary teacher education for generalist teachers [

5,

6], mentioning the lack of conceptual knowledge about musical and pedagogical knowledge. For future secondary music teachers, the situation is different, however, as these students are generally trained musicians with various professional backgrounds and different levels of musical expertise. The challenge consists of linking their professional musical knowledge with specific pedagogical knowledge for creative music teaching. This knowledge is understood here as the ability to design learning situations where pupils can develop their musical creativity in and through specific activities.

According to Beghetto [

7,

8], who examined the topic of creativity in education, three forms of knowledge are identified as dimensions of creative teaching: teaching

about,

for, and

with creativity. Each of them is defined using specific pedagogical aims and a “specific knowledge base” ([

7], p. 550). It is thought that teachers should teach

about creativity by having acquired knowledge of concepts and models specific to creativity, teaching

for creativity while enhancing their students’ creativity using adequate strategies and teaching their subject matter in a creative way—teaching

with creativity. This approach involves recognizing creativity as a skill that can be developed through appropriate teaching strategies. The distinction made between these interrelated categories can be considered problematic, according to earlier research by Jeffrey and Craft [

9] on teaching

for and

with creativity. Nevertheless, it may be helpful to describe specific perspectives of the teaching–learning process in order to identify knowledge for creative teaching. Embodied knowledge and the role of the body must also be considered [

10] for music teaching and learning alongside other domain-specific concepts.

1.1. Dimensions of Creative Pedagogical Knowledge in Music

When teaching

about,

for and

with creativity, specific pedagogical knowledge is described by Beghetto [

7,

8] in reference to Shulman’s concept of pedagogical content knowledge [

11]. This specific knowledge for teaching combines domain-specific content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge. We choose to refer to the terms suggested by Beghetto [

8], understood here as pedagogical content knowledge for creative teaching. Domain-specific references for music education are identified and added for each category.

When teaching

about creativity, teachers should be able to refer to specific models and definitions and help students understand creative phenomena. This is defined as

pedagogical creative domain knowledge (PCdK). Teachers should be able to refer to specific models and definitions to help students understand creative phenomena. In the domain of music education, this means that teachers should be familiar with a general conceptualization of creativity and the specificity of musical creativity, including its epistemological roots. This is in line with Schiavio and Benedek [

12], who suggest going beyond the dichotomies between individual versus collective and domain-specific versus general approaches to musical creativity. These authors underline the importance of having conceptual knowledge about creativity and its epistemological underpinnings in order to orient pedagogical actions. Indeed, as already shown in research on music education, creativity can be conceptualized as a thinking skill within a cognitivist approach [

13], as a social interaction from a socio-constructivist perspective [

14,

15,

16], or as a skillful organism-world adaptation from an enactive point of view [

17].

As musical creativities are multiple and related to specific activities [

18], teachers should be able to identify domain-specific activities such as arranging, improvising, composing, songwriting or creative music listening [

19] through visual or gestural transcreation of music [

20,

21] or music producing [

22]. When teaching

for creativity, teachers are expected to provide adequate activities within a socio-material environment to enhance students’ creativity. Related to teaching strategies,

pedagogical creative enhancement knowledge (PCeK) includes planning and implementing progressive learning activities as well as giving students space for creative expression, changing perspectives, and supporting their autonomy ([

8], p. 231). Music teachers can enhance students’ creativity by organizing progressive stages coherently, for example, from the stage of exploration and assembling musical ideas up to the stage of performing the product and providing a reflection on decision-making, as identified by Giacco [

23,

24]. Moreover, teachers should be able to support students’ learning through techniques named ‘creative scaffolding’ by Giglio [

15,

25], such as providing specific timeframes, spaces, materials, technical support and social organization of students’ interactions. The assessment of the creative process and product in music requires specific expertise, especially for identifying esthetic dimensions [

26], focusing not only on the product but also on the process and the person [

27].

Teaching

with creativity is the third form of creative teaching, as suggested by Beghetto, which focuses on “how teaching can be a creative action in itself” ([

8], p. 231) or, in other words, teaching

with creativity requires action-oriented knowledge. This concept underlines teachers’ need for skills to provide models of creative behavior for their students, exemplifying willingness to take risks, being open to uncertainty, and reacting to students’ unexpected ideas with flexibility. Teachers should be not only entirely comfortable with the teaching content but also be able to perform and embody characteristics of creative action in the “moment-to-moment decision-making in the classroom” ([

7], p. 558). Described by Beghetto as

creative pedagogical domain knowledge (CPdK), it implies a specific stance or attitude toward creativity [

28,

29]. In our view, the teacher’s willingness to confront uncertainty and unexpected results can be considered a conative aspect of teaching [

30], which is inherent to the creative experience [

31]. This includes embodied knowledge, which helps the teacher interact and make decisions according to any given situation. It seems less clear what kind of knowledge teachers should acquire to teach

with creativity. For this reason, we propose that the dimensions of

creative pedagogical domain knowledge could be described with more precision.

1.2. Embodied Knowledge for Creative Music Teaching

The embodied aspect of pedagogical content knowledge for music teachers has been underlined by Bremmer’s research about primary music teachers [

10,

32] and research on embodied music pedagogy [

33,

34]. According to these authors, professional gestures for teaching music can be described as pedagogical gestures of guiding, representing musical features and giving instruction, as well as physical modeling to demonstrate to and engage students, carrying out multimodal assessments in order to give feedback, including touch, if allowed. In creative activities, teachers are also supposed to support students’ autonomy through nonverbal scaffolding gestures. Physical presence and bodily gestures for encouragement [

35], as well as technical gestures for showing how to play music [

15]) are examples of embodied creative scaffolding gestures. According to research on the esthetic and artistic aspects of music-making, a particular type of attention to the overall interactions in the classroom and to the performance of the creative product is unique to collective music-making [

36], specifically in group improvisation [

16,

37]. Without diving deeper into the domain of somaesthetics [

38] or the idea of resonance for classroom interaction in and through music [

39], we underline the role of bodily postures and interactions in enhancing aesthetic experiences during creative music-making.

In research on the body in teaching,

postures can be understood as a primordial expression of action [

40]. These are related to professional gestures but shape the “more or less appropriate, more or less timely, and more or less effective interactions in teaching” ([

40], p. 115, translated by author 1). Understood as a metaphor, postures express a stance toward an object. To summarize, a

posture expresses both a symbolic and a bodily stance toward a teaching situation.

For practitioners in the field of music teacher education, the question is how to design a music didactics course that develops teachers’ pedagogical knowledge about models, concepts and activities (teaching about musical creativity), strategies for planning, accompanying and assessing creative music-making to enhance students’ learning (teaching for musical creativity), and that develops a specific stance and embodied knowledge to “perform” creative music teaching (teaching with creativity).

Consequently, the following research question has been identified: how do students’ perceptions of teaching musical creativity evolve during the second semester of a one-year secondary music teacher education course? The sub-questions are (i) which aspects of the provided knowledge are considered relevant by the student teachers? and (ii) what the role of the body is in terms of being an element of creative pedagogical knowledge?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

In order to understand the evolution of novice music teachers’ perceptions about pedagogical knowledge specific to the topic of creative music teaching, declarative data was collected during a one-year secondary music teacher training course. For this qualitative study, two interview sessions were undertaken halfway through and at the end of the year. Five students, all undergoing professional reconversion, agreed to be interviewed at the beginning and after the end of the second semester (between March/April and June/July 2021). Both sets of semi-structured interviews were designed to glean insights into students’ conceptions of theoretical knowledge about creativity, their own creative practice as musicians, and their teaching strategies, including planning, guiding, and assessing music creation activities. In order to highlight the link between bodily engagement and theoretical understanding, the role of the body in creative music teaching was included in the question set. During the first interview, participants were invited to explain their musical background and their previous experience in music teaching. During the second interview, the participants were asked to illustrate perceived changes in their teaching strategies through examples of their current teaching practice.

2.2. Participants

The five students were all trained musicians aged between 28 and 50 years old with various musical backgrounds (ancient music and musicology; classical music (violin); pop and rock music with a focus on instrumental music; singing and songwriting). Three participants reported that they engaged in regular musical practice in improvisation and/or composition/songwriting (students 1, 3 and 4). One student (5) had no previous personal experience in activities like improvising, composing or listening to creative music. Conceiving music creation activities was new for this participant, who had over 30 years of experience in individual instrumental teaching. Four participants taught regularly at school, with an average of 10 lessons per week. Only student 3 completed an internship accompanied by an experienced teacher (4 lessons per week). All student teachers were enrolled in the training institution for 1 or 2 years to become secondary music teachers. Our sample contains a wide range of ages and musical backgrounds, which is representative of the profile of students who usually participate in this course. Due to the small sample size, no general conclusions can be drawn about the link between previous musical instruction, life experience and changes observed during the course.

2.3. Course Description

The aim of this one-year music didactics course was to assist teacher candidates with a professional music background in acquiring professional knowledge and developing their identity as secondary education music teachers. During the course, various models were presented related to creativity as well as to teaching strategies suited to student teachers’ multiple identity facets as artists, musicians, reflective practitioners and educators [

41].

The combination of various models was intended to support the transformative process that occurs during teacher training by valuing students’ specific professional knowledge of music. As embodied musical knowledge and the role of the teacher’s body were cross-cutting themes throughout the course, we thought that these aspects would be particularly developed over the semester. In any case, our primary objective was for students to acquire relevant pedagogical knowledge. Referencing their identities as artists and musicians was intended to reduce potential tensions between artistic and pedagogical goals during teacher training [

42]. During the first semester, student teachers worked on planning and assessment strategies by designing and analyzing a short teaching sequence of four lessons. In the second semester, which is the focus of this paper, the emphasis was on conceiving at least six lessons to foster musical creativity. In this course, creativity was understood as the ability to create something new but adapted to a given context. To develop this ability in music education, the student teachers had to conceive specific activities. It was up to the students to select these activities according to their own musical expertise. Sample tasks included songwriting, composing with digital tools, improvising and producing music without limiting musical genres.

As a first step in this process, participants experienced different musical activities in order to become aware of their own creative strategies and musical knowledge for teaching. The student teachers experienced activities of music listening through gestural and visual transcreations, arranging for Orff instruments, and improvising or composing using the voice, body percussion or instruments. The second step was first to reflect on the creative process and on definitions of creativity generally and in music, and secondly, to understand theoretical underpinnings in order to acquire pedagogical creative domain knowledge about creativity. In the third step, planning, guiding and assessment strategies were presented, applied and analyzed through several short design activities to develop their pedagogical creative enhancement knowledge. The whole course was designed to experience musical and pedagogical creativity by stimulating future secondary school teachers’ reflections on their personal stances toward musical creativity in order to enhance their capacity to teach musical creativity in alignment with their own musical backgrounds. Some teaching experiences at their school internships were discussed during a final presentation, partly supported by a selection of traces of their teaching (audio, video and photos). Over the whole semester, the participants received formative feedback about their capacity to design, assess and analyze lessons fostering musical creativity.

The following table (

Table 1) illustrates the creative pedagogical knowledge presented during this course. The theoretical concepts were illustrated and experienced through concrete examples of activities during the course.

2.4. Data Analysis

Each interview was transcribed for thematic analysis [

43]. The interviews were read by the first and second authors of this contribution to identify emerging themes and confirm established categories. Three broad categories were identified, representing dimensions of creative pedagogical knowledge and specific topics of the course: (1) knowledge about creativity in general or in music, (2) knowledge about teaching strategies and (3) knowledge about their creative practices and stances toward creativity including professional identity facets, and the role of the body in music education. Data specific to the category of

pedagogical creative enhancement knowledge (PCeK) were divided into subcategories to distinguish between planning, guiding/scaffolding and assessment strategies. To redefine

creative pedagogical domain knowledge (CPdK), we proposed the term

creative stance knowledge (CSK). This knowledge is related to professional postures [

40] toward creativity, which contain symbolic dimensions such as openness to uncertainty or flexibility and an embodied dimension representing enhancing feelings of trust and confidence for fostering aesthetic experiences. This concept will be further defined and explained in the results section.

The system of coding was repeatedly verified via numerous discussions between the authors, and a crosscheck of the coded verbatims was conducted by Author 3. Data specific to the evolution of students’ perceptions were identified by classifying their interview data according to the three main categories of teaching

about/

for/

with creativity and their related subcategories. The table below (

Table 2) details the content of the codes and provides some examples from the data.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

Each participant gave their written and oral consent to participate in this study and to use the anonymized interview data for research according to the ethical guidelines of the University of Teacher Education, State of Vaud/HEP Vaud. No further ethical approval from the cantonal ethics committee was required for interviews with student teachers.

3. Results

3.1. Creative Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Teaching about and for Creativity in Music

Knowledge about models, definitions and strategies for teaching musical creativity appears to be strongly interrelated. All students reported having gained confidence in planning and guiding music creation activities that are generally perceived as challenging in secondary schools. Participants partially referred to the definitions and models presented during the course. The main changes in their understanding can be summarized as follows:

Importance of constraints (planning) and precise instructions (guiding);

Awareness of obstacles and challenges for the conception of the activities, especially in relation to time, spatial and material conditions and the place of musical knowledge (planning);

Identification of specific creative scaffolding gestures (guiding);

Assessment of the creative process and pupils’ intentions when using specific tools.

The need for constraints, like clear rules for music making, time framing and pupils’ interactions to enhance learning, was mentioned during the first interview by two participants. During the second interview, this theme was explicitly or implicitly discussed by all student teachers. Even the participants with significant prior experience in teaching underline the need for precise rules, but several questions about concrete activities remained, as stated by student 2: “It’s funny to say it like that, but sometimes putting up barriers allows them to go further than simply finding themselves in front of a blank page and thinking, my god, how am I going to do this?” (Int2_line 10). They underlined the importance of precise instructions related to constraints and the need for space for musical expression. Both themes are tightly linked to the understanding of creativity as a process that can be fostered by providing specific learning conditions.

It seems surprising that students spoke about their difficulties more precisely at the end than at the beginning of the course. We surmised that this reveals a deeper understanding of teaching strategies for these activities over time. This developing understanding led all participants to ultimately report having greater confidence in planning and performing music creation activities at the end of the semester. The evolution of student 5—who had no prior creative teaching experience—was striking, as she progressively started to undertake creative activities with pleasure and confidence in each lesson: “I never used to do it before, until I started doing didactics and from the start of the interviews which were before Easter, if I remember correctly, in fact—I do it in practically every class” (Int2_line 1).

Scaffolding gestures to support and guide the creative learning process were mentioned on different levels by all students but without explicit reference to the concept of creative scaffolding [

15]. Increasing awareness of creating space for pupils’ ideas by providing technical support without providing actual solutions or ideas was explicitly mentioned (students 1, 2 and 3). As these gestures are tightly linked to what we call

creative stance knowledge, more results are presented in the next section.

Assessment of music creation activities raised many questions for participants, which remained partly unanswered even at the end of the course. Nevertheless, participants reported their increased awareness of tools such as continuous feedback on the process and the use of a logbook to document not only the steps of the process but also the pupils’ reasoning about the process.

3.2. Teaching with Musical Creativity—A Twofold Questioning about Creative Stance Knowledge

Participants’ principal evolutions can be encapsulated in two points:

Teachers’ creative stance knowledge and scaffolding strategies are interrelated;

Knowledge about teacher identity facets is linked to awareness of their stance toward creativity and to their own creative practice.

As previously mentioned, teachers’ attitudes toward creativity influence their ways of performing creative teaching. Creativity is a means to learn musical concepts (student 5), foster pupils’ autonomy (student 4) and give space to unexpected ideas (student 2). Teaching music creatively encourages the teacher to abandon control (“lâcher-prise”—“to let go”, all students). Knowledge about the teacher’s stance as a facilitator who should hold back their own personal creative solutions is touched on by student 1, for example: “We all have our preferences, our opinions and things like that. But the idea, in fact, is not necessarily to develop something that will impose that vision. In other words, these visions can be one possible choice among others. But you have to be able to see that there are other choices too” (Int2_line 13).

The participants’ own identity as an artist, understood in this context as teachers’ ability to create, was discussed through the lens of professional identity facets, a model also presented during the course. A transfer was noted between their personal prior or current creative practice (or lack of), passing through a process of understanding this creative practice (students 1, 2 and 4) to discover their ability to teach with creativity (student 5). Interestingly, theoretical understanding of the creative process, related teaching strategies, and explicit reflections about their professional posture during the course were influenced partly by their views on their creative practice, as expressed by student 1: “And even in my practice as a musician, it also gave me other visions, other perspectives on my personal practice” (Int2_line 11). The challenge is twofold, as the knowledge of how to integrate their identity as an artist and musician is related to their values and the legitimacy they accord themselves to have an artist’s posture at school (students 4 and 5). Knowledge about these potential stances contributes to establishing their role as a music teacher at school, “to know that, with [their] artistic hat on, [they have] a place in the class too” (student 3, Int2_line 18). Moreover, the encounter with student’s creativity resonates with their own creativity (student 2).

3.3. Music Teacher’s Body: Emerging Aspects

As reported by participants, the teacher’s body plays an important role in modeling activities, guiding creative activities and embodying a stance toward creativity in music. Comparisons of transcripts from the two interviews can be described as “evolution” rather than ‘confirmation’ of existing knowledge, which gradually becomes more explicit. As the role of embodied knowledge was highlighted over both semesters of the course, the absence of a clear evolution in this sense was a surprise. Different topics relating to the body were evoked in the first interview and extended in the second: modeling and supporting technical aspects such as meter and synchronization for music creation activities (students 1, 4 and 5); developing students’ embodied musical knowledge (student 1); using scaffolding gestures to support collective musical performance and support pupils’ learning (students 2, 3 and 5), giving multimodal feedback (student 4); fostering non-verbal connections and trust (students 2 and 4). The teachers declared that they used their bodies for modeling, guiding, scaffolding and giving feedback, but aspects related to aesthetic experiences, such as specific embodied attention during the performance, were absent. Bodily stances for enhancing creativity are mentioned as probably important: “In other words, some students will decide whether or not they are interested based solely on non-verbal language. What does the teacher emanate?” (student 1, Int1_line 20). However, specific knowledge is missing as students formulate questions or assumptions rather than stating convictions. For example, becoming aware of eye contact or bodily postures that can encourage communication and collaboration seems to be a first step toward creative stance knowledge, but the question remains: how can we develop this knowledge during the course? The use of videos is suggested by participants to improve their understanding of this topic (students 2 and 4).

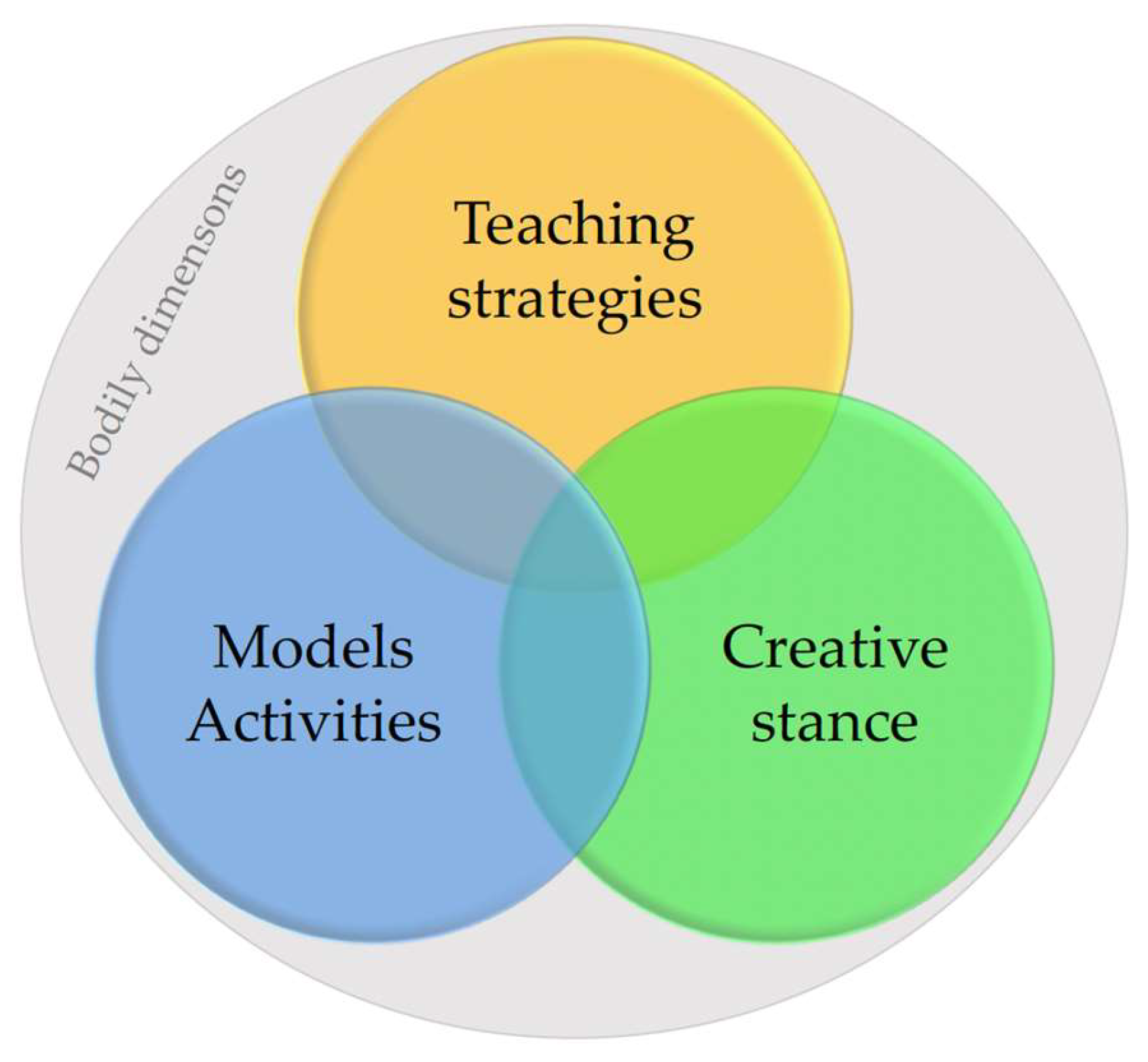

As shown by the results, the three dimensions of creative pedagogical knowledge—knowledge

about models and activities, strategies

for teaching and the creative stance knowledge to teach

with creativity—are interrelated (

Figure 1). Underlying bodily dimensions of creative pedagogical knowledge could be more explicitly treated during the course.

4. Discussion

The change and growth observed in student teachers’ perceptions about teaching musical creativity in secondary music education lead us to discuss the nature of provided knowledge, described according to Beghetto [

7,

8] as

creative pedagogical knowledge. We build on the findings presented, further discussing the concept of

creative stance knowledge and its symbolic and bodily dimensions.

The observed emphasis on teaching strategies by the students, conceived as

creative pedagogical enhancement knowledge, makes us consider the relation between theoretical models as knowledge about teaching creativity and strategies for teaching in music education. Knowledge about definitions of creativity in general and specifically in music seems to be helpful [

1] but requires clarification for teaching practice in terms of its epistemological roots. All models used for the course are rooted in cognitivist or socio-constructivist approaches to creativity. The essentials for lesson design concern the implementation of multiple pedagogical constraints that relate directly to models and definitions of creativity, both generally and in the music-specific domain. This analysis encourages us to reflect on Schiavio and Benedek’s suggestion [

12] for overcoming dichotomic views on domain-specific and general creativity. Pedagogical constraints are related to (i) music—how to generate new ideas involving convergent and divergent thinking [

3] and (ii) time, space, materials and group management, as affordances of environmental constraints in pedagogy [

30]. The usefulness of these constraints in creative music teaching is underlined by students as a condition for creativity. This involves becoming aware of the balance or continuum between openness and maintaining constraints [

44]. Nevertheless, pedagogical knowledge about how to deal with constraints in creative music education must still be further developed in subsequent research projects.

Knowledge about specific activities is not identified as a challenge but rather as organizing progressive, collective activities to undertake within a given time, space and material conditions. Interestingly, the models presented summarize teaching strategies for music creation, identifying different steps or stages [

24]. However, it is still necessary to explain the role of the teacher in relation to which kind of activities to choose, how to frame the activities, and what links to make with music learning in general, or how to assess learning outcomes. The participants did not explicitly mention the teacher’s role in terms of these activities.

An enactive view on creativity (4E creativity, [

17,

45]) could be explored to strengthen associations with embodied

creative pedagogical knowledge underlined by Beghetto [

7,

8], but this concept is not yet operationalized in music education research. From a sociological perspective, reflections on musical creativity as a dialogical principle of resonance [

39] could integrate the verbal and non-verbal interactions and atmospheres reported on by the student teachers. This epistemological reorientation could help to express implicit knowledge for creative music teaching and support students’ autonomy.

This leads to discussing creative stance knowledge proposed as a concept emerging from our findings. As the student teachers point out, this involves an awareness of specific attitudes toward students’ creative and unexpected ideas. This knowledge could help teachers to direct creative processes by relinquishing control over students’ results to a certain extent.

Symbolic and embodied dimensions can be identified. The symbolic dimension is related to openness, flexibility and willingness to deal with uncertainty [

7,

8]. This involves creating an appropriate socio-emotional environment characterized by a feeling of emotional security, confidence and openness to failure. It requires the teacher to create a specific atmosphere that encourages creative and collective musical creation in the classroom [

16,

37].

The embodied dimension of

creative stance knowledge can be related to research on

pedagogical content knowledge for music teaching [

10], as teaching gestures and multiple functions of the teacher’s body during classroom interaction are central. To deepen this aspect in teacher education, music-specific and pedagogical gestures for activities of music creation could be described in more detail.

Thus, the embodied dimension of

creative stance knowledge is in line with an enactive view of creativity, itself based on an embodied, embedded, enactive and extended understanding of cognition [

17]. The “moment-to-moment contingency” (each person’s action depends on the action just before) mentioned by the authors echoes Beghetto’s description of enacted knowledge to teach with creativity ([

7], p. 558). This approach could offer a more dynamic view of classroom interactions, considering the subjective perspective of the teacher.

Both dimensions of

creative stance knowledge involve the professional posture of the teacher—the capacity to react and interact with students at the right moment, using context-appropriate gestures [

40]. Professional posture implies aspects of professional identity that are mentioned by the participants. They understand music teacher identity facets (artist/musician/reflective practitioner/educator) [

41] as

pedagogical knowledge, making them aware of the mutual influence between their creative practices and their ongoing identity formations as teachers. We argue that in creative teaching, the artistic dimension of music teachers’ practice can contribute to understanding and conceptualizing the subjective experience. It is worthwhile to give specific attention to the role of the body in musical, creative and aesthetic experiences [

38] in the context of interperson [

37], intraperson [

36], and person-world [

31] encounters. This could be considered as specific knowledge inherent to musical practice.