Abstract

With the increased social-emotional needs of students since the COVID-19 pandemic, schools offer an opportunity to support student wellness and address needs. This article describes one district’s efforts to develop a systematic, equitable, and collaborative continuum of supports. The district used Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funding from the U.S. Department of Education to establish new initiatives and support for students experiencing mental health struggles. These initiatives and supports include hiring a school social worker, a multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) framework, implementing universal screening tools for early identification and intervention, using data-driven decision-making, and incorporating progress monitoring efforts to document the impact of services and supports that have been provided to their students. As new initiatives with time limited funding often fail to make a lasting impact, using sustainability strategies is critical. This article describes the district’s systematic, equitable, and collaborative approaches with sustainability considerations. We also describe barriers and next steps to assist other districts in planning for change. We conclude with a discussion of implications for practice and research.

1. Introduction

This special issue highlights four guiding principles to innovate school mental health practices: systematic, sustainable, equitable, and collaborative. However, schools should work towards incorporating all guiding principles in order to efficiently and effectively support wellness for students and staff. As such, this article reviews one district’s approach to considering sustainability within systematic, equitable, and collaborative practices. We will demonstrate how the district systematically planned a continuum of supports and worked towards improving equity and collaboration. We will also identify lessons learned, implications for practice, and areas for future research.

Every year across the United States, one in six children aged 6–17 years old experiences a mental health disorder [1]; yet it takes approximately 11 years to initially contact mental health professionals to request treatment [2]. Kessler et al. [3] explain that 50% of the mental health disorder cases begin by the age of 14 and 75% of the cases begin by the age of 24. Due to the early onset of these cases, approximately half of the American population “will meet the criteria for a DSM-IV disorder [at] some time in their life” [3] (pp. 593, 600), making prevention strategies for mental health disorders crucial. As students’ social-emotional needs have increased and intensified since the COVID-19 pandemic [4], many schools and districts have begun new initiatives with COVID-19 relief funding. This plan is referred to as the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) under the American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act of 2021. The U.S. Department of Education [5] authorized $122 billion to schools across the nation in efforts to address “academic, social, emotional, and mental health needs of students”. However, new initiatives and supports are futile if there are no intentional efforts to plan for sustainability.

Sustainability is defined as “the extent to which a newly implemented treatment is maintained or institutionalized within a service setting’s ongoing, stable operations” [6] (p. 70). According to the Ohio School Wellness Initiative [7], sustainability includes maintainable, adaptable, and flexible approaches and is a critical component to implementing the Student Assistance Program (SAP) and staff wellness frameworks. Typically, grant funding lasts from 3 to 5 years with the expectation of additionally obtaining funding from other resources or identify local funds to support ongoing implementation. While research has only been conducted broadly on programs after funding has ended, many program components remain active as they have become embedded within the foundation and principles of the programs [8]. Alternatively, time and a lack of sustainable planning constitute the termination of many programs after funding has ended. According to a systematic review of 10 online databases and relevant websites that focused on and categorized keywords such as “sustainability”, “school”, “intervention”, “mental health”, and “emotional wellbeing” [9], staff engagement, motivation, efforts, and adaptations facilitate sustainability in schools, yet a key barrier to this and the fidelity of implementations is a lack of availability to train new staff to effectively deliver the interventions confidently.

Schools can use specific strategies to facilitate the sustainability of new initiatives. Hailemariam et al. [10] conducted a systematic review of 26 articles that considered sustainability strategies for public health evidence-based interventions. The authors identified nine sustainability strategies, including (in order of frequency) funding and/or contracting for continued use, maintenance of workforce skills, adaptation to improve fit and alignment with organization procedures, systematic adaptation, leaders prioritizing and supporting continued use, priorities and needs aligned with the practice, maintenance of staff buy-in and access to new or existing money, and monitoring effectiveness. The authors also noted that the presence of funding facilitated sustainability, while limited or eliminated funding was the most frequent hindering factor. Results highlight the need to consider sustainability and funding when planning and implementing new initiatives.

Purpose

Given the importance of sustainability considerations, this article aims to inform readers of one district’s approach to considering sustainability within systematic, collaborative, and equitable practices. Below, we will identify district demographics, describe district systematic, equitable, and collaborative approaches, and attend to sustainability considerations and strategies. We will then discuss the implications for research and practice.

2. Materials and Methods: Case Example

2.1. School Context and Background

Patrick Henry Local Schools is a rural school district in Hamler, Ohio. The district is unique in nature, as the current school district is the result of several small communities consolidating into one school district. The Patrick Henry district spans 144 square miles, houses grades preK–12 in one building, and currently has roughly 1000 students enrolled. Of the student population, approximately 37% of enrolled students qualify and receive free and reduced lunches. The Patrick Henry community is primarily agricultural, with an emphasis on small town values and traditions, including family, and celebrating community history through festivals held throughout the communities that make up the district. The district mission statement is to “create an environment where all students discover their personal best in every opportunity”. Additionally, their vision consists of three pillars: (a) Family— being the best version of self for others, (b) Perseverance—being the best version of self in difficult times, and (c) Above and Beyond— being the best version of self when no one is looking.

Due to a rise in student social-emotional needs, Patrick Henry Local Schools has seen a shift in the urgency for both an increase in staffing and prevention programming. The district created a mental health team on campus in 2022 to address the growing needs of the student population. This team includes three school counselors, a school social worker, a school psychologist, and a behavioral health and wellness coordinator who all work closely with the administrative staff to promote both student and staff wellness. Patrick Henry Local Schools acknowledged that for many of their students, school is a resource that can be utilized to receive both academic and social-emotional support. The district believes that if schools do not address the mental health of their students, academic health will not flourish. This has been a driving force in ensuring the necessary steps are taken to meet the needs of their students. Next, we will describe how the district addressed systematic, equitable, and collaborative approaches to support mental health, and we will review sustainability considerations within each section.

2.1.1. Systematic

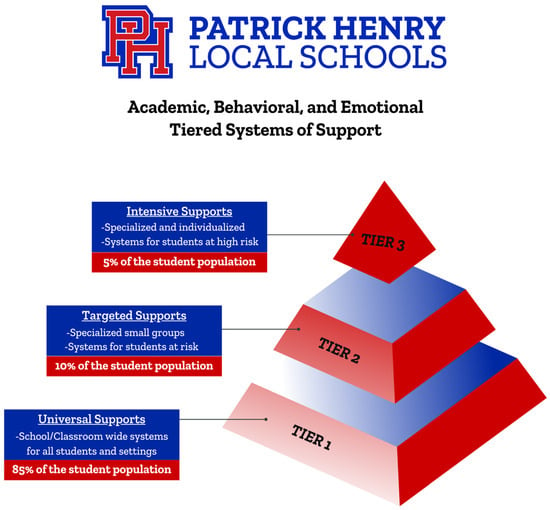

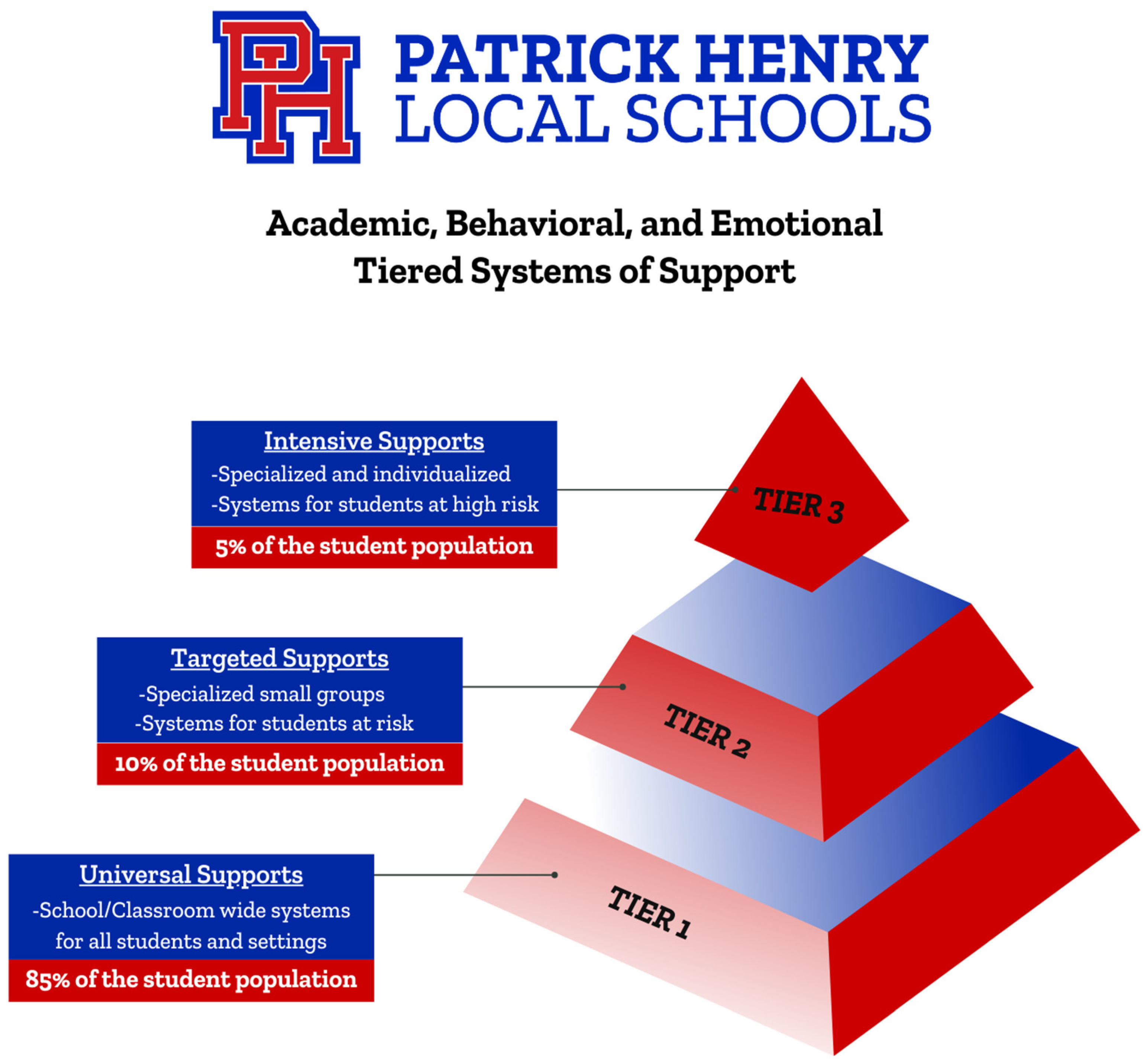

According to the Ohio School Wellness Initiative [7], systematic approaches are efficient, data-driven, and structured. The National Center for School Mental Health [11] highlights the importance of systematic processes when designing and implementing comprehensive school mental health programs. This includes the use of data on needs and resources, multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS), universal screening tools that facilitate early identification and intervention, data-driven decisions, and tracking outcomes to document the impact of services and supports. The use of MTSS to address the academic, behavioral, and social-emotional needs of students has become the standard of practice at Patrick Henry Middle School. To effectively address the needs of students in grades 5–8, it is vital to create a systematic mechanism to identify students in need, provide appropriate interventions, and implement progress monitoring tools to determine the effectiveness of the interventions that are implemented. In this section, the Student Assistance Program (SAP) model will be discussed, followed by the continuum of supports that are provided throughout the program.

In the spring of 2021, Patrick Henry Middle School principal Kaylene Atkinson applied for an initial grant to pilot the Ohio School Wellness Initiative’s model for an SAP and staff wellness during the 2021–2022 school year [7]. As a pilot school, Patrick Henry Middle School received OSWI grant funding to develop the SAP process, supply resources to guide the development and implementation of an SAP and provide opportunities for staff wellness. The pilot work included the creation of an SAP, which promotes upstream prevention measures to be taken for students to be identified before a crisis occurs [7]. Within the SAP, Patrick Henry Middle School implemented a Student Assistance Team (SAT) consisting of teachers from each grade level (including intervention specialists), the school counselors, the school social worker, the Behavioral Health and Wellness Coordinator, and the middle school principal to further enhance the process for identifying students who were beginning to struggle academically, behaviorally, or social-emotionally. Data, such as academic testing, a universal screener, anecdotal records, achievement scores, behavior charts, the Closegap program, school counselors’ meetings with students, and parent or teacher concerns, was used to place students in the appropriate tier of support (see Figure A1).

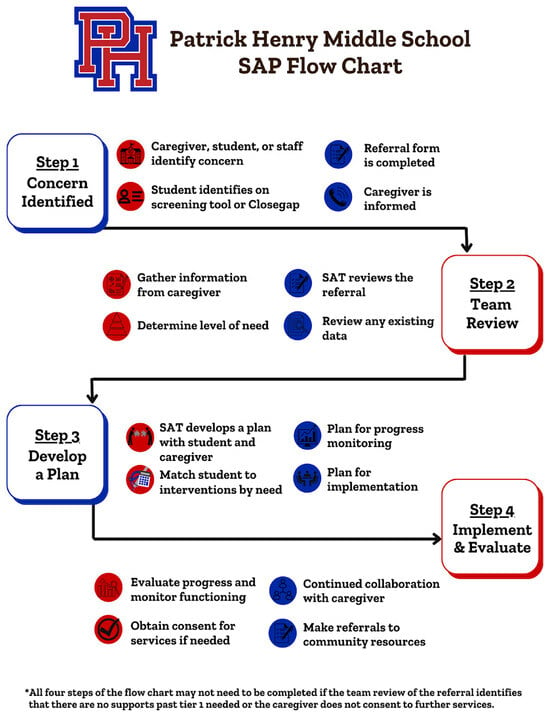

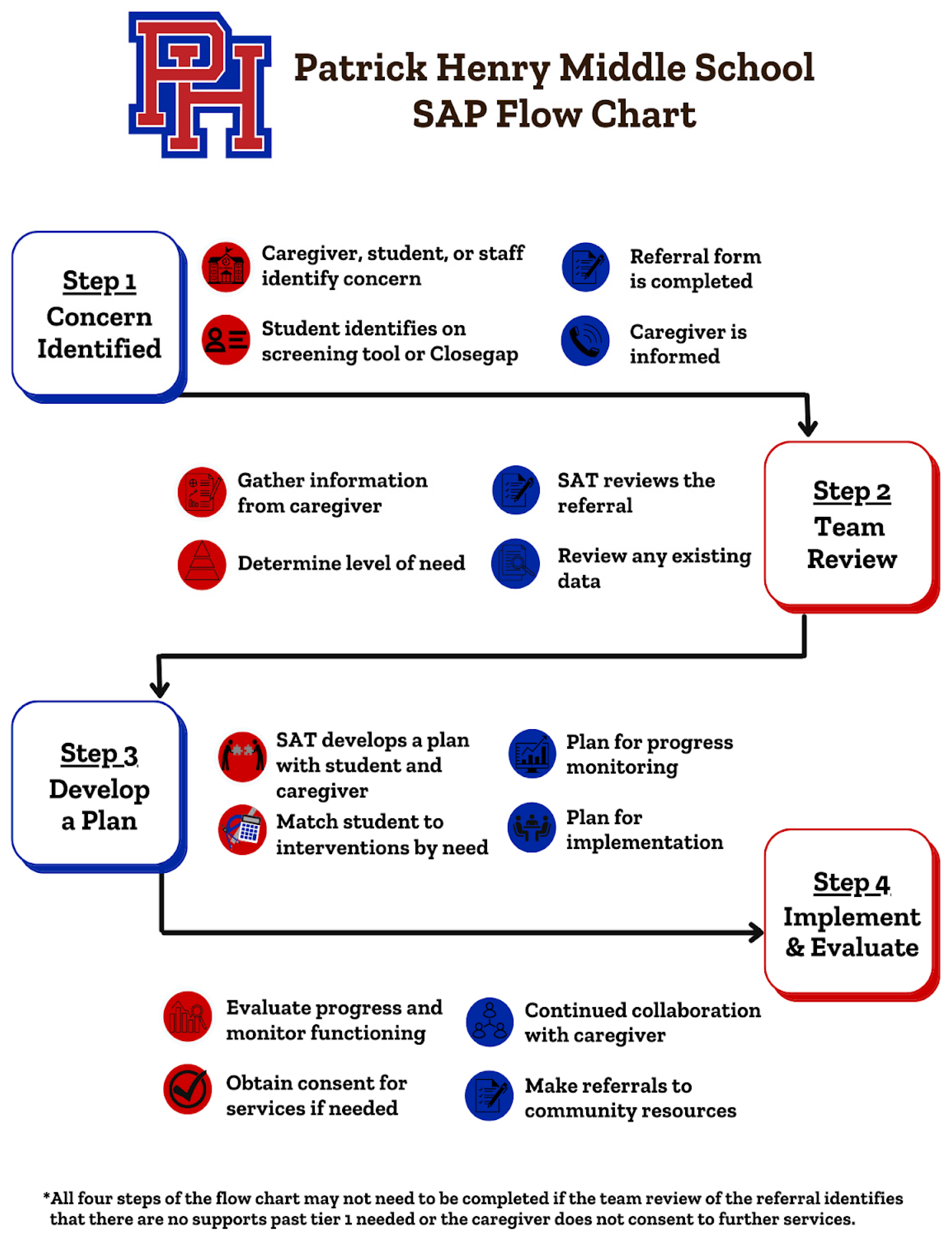

To guide the implementation process, various documents were created, such as SAP Referral Forms, an SAP Flow Chart, and an SAP Parent Manual based on the Ohio School Wellness Initiative Model [7] (see the Ohio School Wellness Initiative website for templates and resources). The SAP Flow Chart (see Figure A2) guided the process and allowed the team to work collaboratively and operate efficiently during meetings. Throughout each grade-level SAT meeting, the members reviewed referrals completed by teachers, staff, parents, and self-reporting students. Members also reviewed the universal screener results administered by the SAT to systematically identify struggling students before a crisis occurred. The referred and/or identified students then began receiving SAP supports. Each grade-level SAT met quarterly to identify students for the SAP process, determine interventions, and review the appropriate progress monitoring tools that were previously put in place.

After the first screening in October 2022, 32 students were initially referred to the SAP. The SAP process identified the Tier 2 and Tier 3 needs of students who were flagged by the screener and, therefore, provided valuable insight into students’ perspectives on their own functioning. After the screener’s results were analyzed within the SAT, relevant interventions were chosen for each student. SAP Tier 2 interventions included mentoring, check-ins, small groups for specific skills, and one-on-one support. Teachers provided classroom support, and if additional support/interventions were needed, the school counselors or school social worker provided further assistance. Following the first SAP meeting in November 2022, 27 students qualified for Tier 2 SAP services. By January 2023, 4 students were moved to an “on watch” status, while 6 new referrals were made, totaling 33 students active in the SAP. However, in May 2023, only 31 students remained due to 2 students who moved out of the district. Within the first year of the SAP program, 42% of SAP students met or exceeded their intervention goals, prompting the students to be “on watch”, while 74% of all SAP students in the program showed data increases toward their goal.

In the elementary school, a standard Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) is used to address academic concerns in grades K–4. This process consists of the MTSS team meeting with each grade level teacher to review students who may need additional support. To address any social-emotional needs that come up during an MTSS meeting, a separate meeting is scheduled with the student’s teachers, principal, director of student services, the elementary school counselor, and the student’s parents/guardians. The high school is currently in the process of examining the work being carried out in the middle school through their SAP process with the hope of implementing their own version of the SAP during the 2024–2025 school year.

Continuum of Supports

In order to support the goal of social-emotional wellness for all students, prevention programming was offered at the Tier 1 level, meaning all students, regardless of their needs, received prevention programming. Examples of Tier 1 social-emotional programming used throughout the district included Signs of Suicide [12], Project Respect [13], Safe Dates [14], ROX—Ruling Our Experiences [15], Start with Hello [16], and Play It Safe [17]. Tier 1 programming was selected by reviewing programs that were offered by local mental health agencies that focused on addressing the challenges all students face by providing targeted academic and mental health aid.

To efficiently and proactively identify students for additional support, students in grades 5–8 were administered a social-emotional screener through a Google Form during their Academic Assistance period. The screener was locally developed by the team to gain specific insight on students’ perceptions of Patrick Henry in relation to their mental health at school. This also assisted students in identifying their own perceived needs for academic, behavioral, or social-emotional functioning through a series of multiple-choice questions and short answer responses. Additionally, the screener examined executive functioning, supportive relationships, school engagement, the perspective of school climate, and engagement with peers. Overall, 298 students were screened in October 2022, followed by a screening of 223 students in May 2023. The results were then analyzed and discussed within grade-level SATs, where the overall social-emotional health of students at Patrick Henry went from an average of 67% in the fall to 73% in the spring, indicating a 6% increase in overall middle-school student social-emotional health.

During the 2022–2023 school year, the middle school also implemented Closegap [18], a free social-emotional check-in platform that allows concerns to be addressed in real time. The middle school selected Closegap to provide students in grades 5–8 with an additional way to inform trusted adults at school that they were struggling and in need of support. Closegap was implemented in November 2022 and completed by all middle school students each Monday for one month. Closegap generated data in real time, allowing select staff members and each individual student to see trends in mood, energy level, and week-to-week social-emotional progression. After the initial mandated month of Closegap check-ins, students were able to complete a check-in using this platform as needed. This allowed for a more personal and private way for students to seek help. After using Closegap to self-report a need, counselors or the school social worker met individually with students to provide support and prepare the student to transition back into the classroom environment. During the 2022–2023 school year, there were 588 total check-ins completed by students using the Closegap platform in the middle school, while 48 of those check-ins were optionally completed by students after the required timeframe ended.

When students were identified for additional support at the Tier 2 level, the school counselors and the school psychologist provided direct support to best meet the social-emotional needs of students outside the classroom setting. Tier 2 academic and behavioral supports included small group instruction, one-on-one tutoring, text-read-aloud supports, and text-to-speech accommodations when appropriate. Tier 3 academic supports included evaluations for a suspected disability, resource room placement, working with an intervention specialist, and direct instruction to provide maximum support for students with the greatest needs.

For social and emotional needs at the Tier 3 level, the school social worker provided ongoing mental health counseling to K–12 students who were referred for these services through the referral process. Due to the rural location of the Patrick Henry School District, the closest mental health agencies are 20–30 min from most student residences. The hiring of a school social worker, who is independently licensed, allowed the district to provide direct mental health services to students in need, effectively eliminating the need for transportation and the cost-of-service barriers that students and families were facing. Since the addition of the school social worker in 2021, 68 different students have received services, with 1859 individual therapy sessions provided by the social worker. Of those students, 31 (46%) met and maintained their treatment goals, allowing them to graduate from social work services. The school social worker has completed 33 diagnostic assessments, 93 crisis screens, made 22 referrals to outside mental health agencies such as psychiatric services, and completed an additional 106 therapy sessions over 40 summer workdays since 2021.

Methods for Supports

At Patrick Henry, all student concerns in grades K–12 start with the student meeting with their school counselor. When a social-emotional need is identified, the school counselor begins meeting with the student as Tier 2 targeted support. The counselor provides support for the student and develops interventions to help the student function more efficiently in the classroom. These Tier 2 meetings help the counselor monitor student progress and eventually determine if the student would benefit from being moved from the Tier 2 level of intervention to Tier 3. After roughly 4 weeks of meeting with a student, the school counselor either keeps the student on their caseload or shares their concerns with the building principal to discuss a potential referral to the school social worker.

The referral process is as follows:

- A mental health concern was previously identified, prompting the school counselor to begin meeting with the student to address the concern.

- The school counselor determines through their meetings with the student that an ongoing mental health need is present and shares these concerns with the building principal.

- The school counselor meets with the school social worker to discuss possibly referring an identified, Tier 2 student to receive Tier 3 services from the school social worker. If the social worker has room on their caseload and feels the student would benefit from social services, the counselor will proceed with the referral process.

- The school counselor calls the student’s parents/guardians to discuss referring their student to receive social work services and obtains verbal consent to make the referral.

- Once verbal consent has been received, the counselor meets with the building principal, who completes a Google referral form that is sent to the social worker.

- The social worker receives the referral and calls the student’s parent/guardian to complete a questionnaire that provides insight into what their student has been experiencing, any necessary background information the social worker should be aware of, and the goals they have for their student’s treatment.

- The social worker has an initial meeting with the student to complete a diagnostic assessment, identify the student’s perspective, personal goals for treatment, and the frequency of their sessions.

- The social worker begins regular meetings with the student and assists the student in working towards their mental health treatment goals.

Once a student meets and maintains their treatment goals, and there are no new goals identified, the termination process begins between the student and social worker. The student will begin meeting less frequently with the social worker, review their progress made during treatment, and identify how to handle potential situations on their own once the termination process has been completed. When the termination process is finished, the student “graduates” from social work services and meets with the social worker as needed. There is not a maximum or minimum number of counseling sessions a student may receive from the social worker, as each student’s needs and home life are unique and impact how long a student may need to receive this level of support. On average, the social worker will complete between 20 and 25 individual sessions with students each week.

The referral process is typically followed with fidelity; however, there are a few high-risk scenarios where students may be directly added to the social worker’s caseload rather than receiving four weeks of support from the counselor. This only occurs if the student is in need of immediate mental health services (i.e., attempted suicide) or a special-education mandated social work intervention is identified for a newly enrolled student. If the social worker’s caseload has reached capacity, this is communicated to the three school counselors. They will then refer any future students who may need additional support to local, outside mental health agencies, and the school counselors will continue providing support to these students as needed. To efficiently maintain student support, the social worker consistently communicates the status of her caseload to the school counselors regarding when space becomes available on her caseload again.

School social work services require informed consent from parents or guardians to provide ongoing services. The social worker receives both verbal and written consent to provide services to students who are referred for mental health counseling. In the event that a parent does not consent to their student meeting with the school social worker, the student’s school counselor will continue to meet with the student to provide support as needed and may recommend a referral for outside therapy services. However, since the district has employed a social worker directly, the majority of parents have consented to allow their students to receive services from the school social worker.

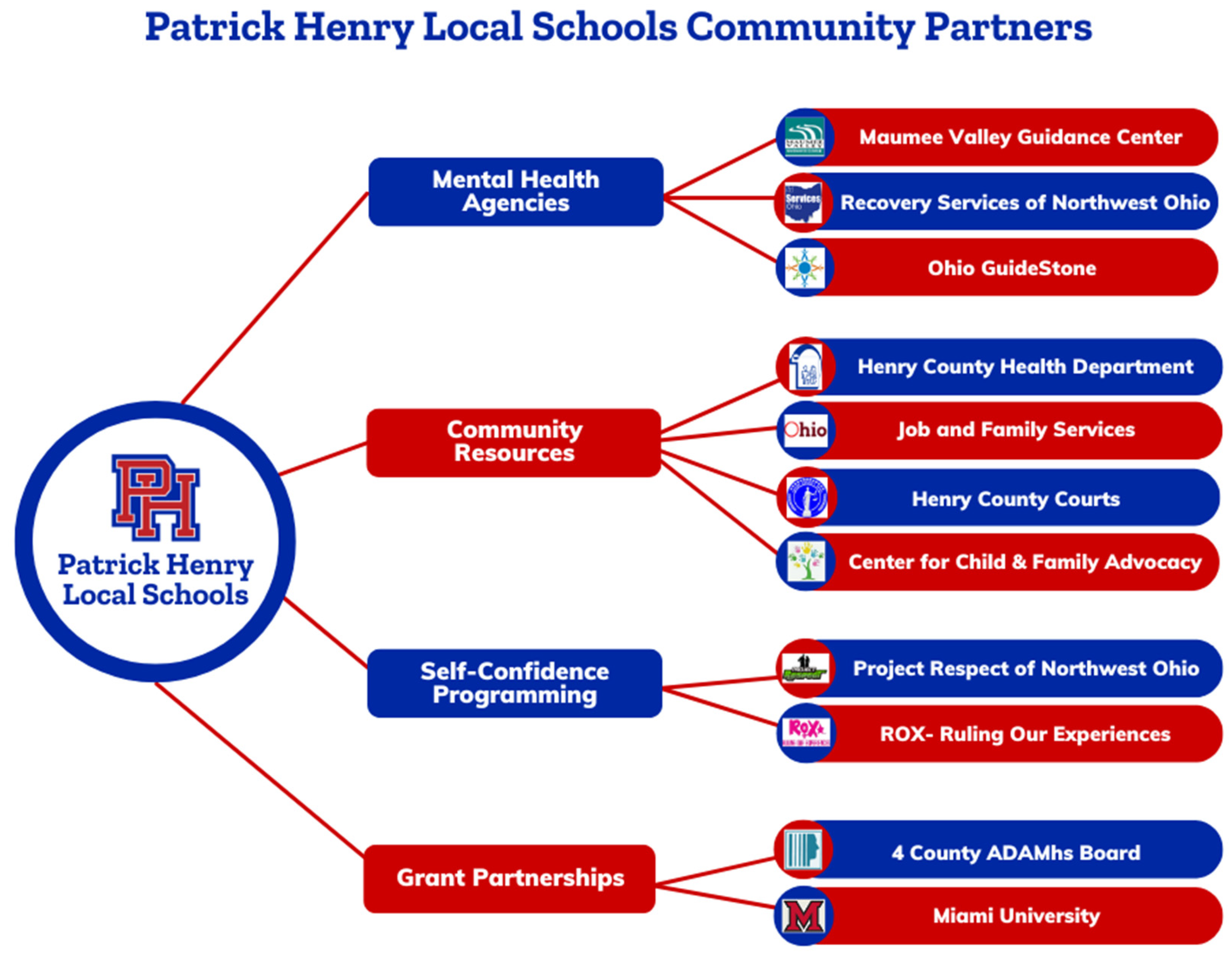

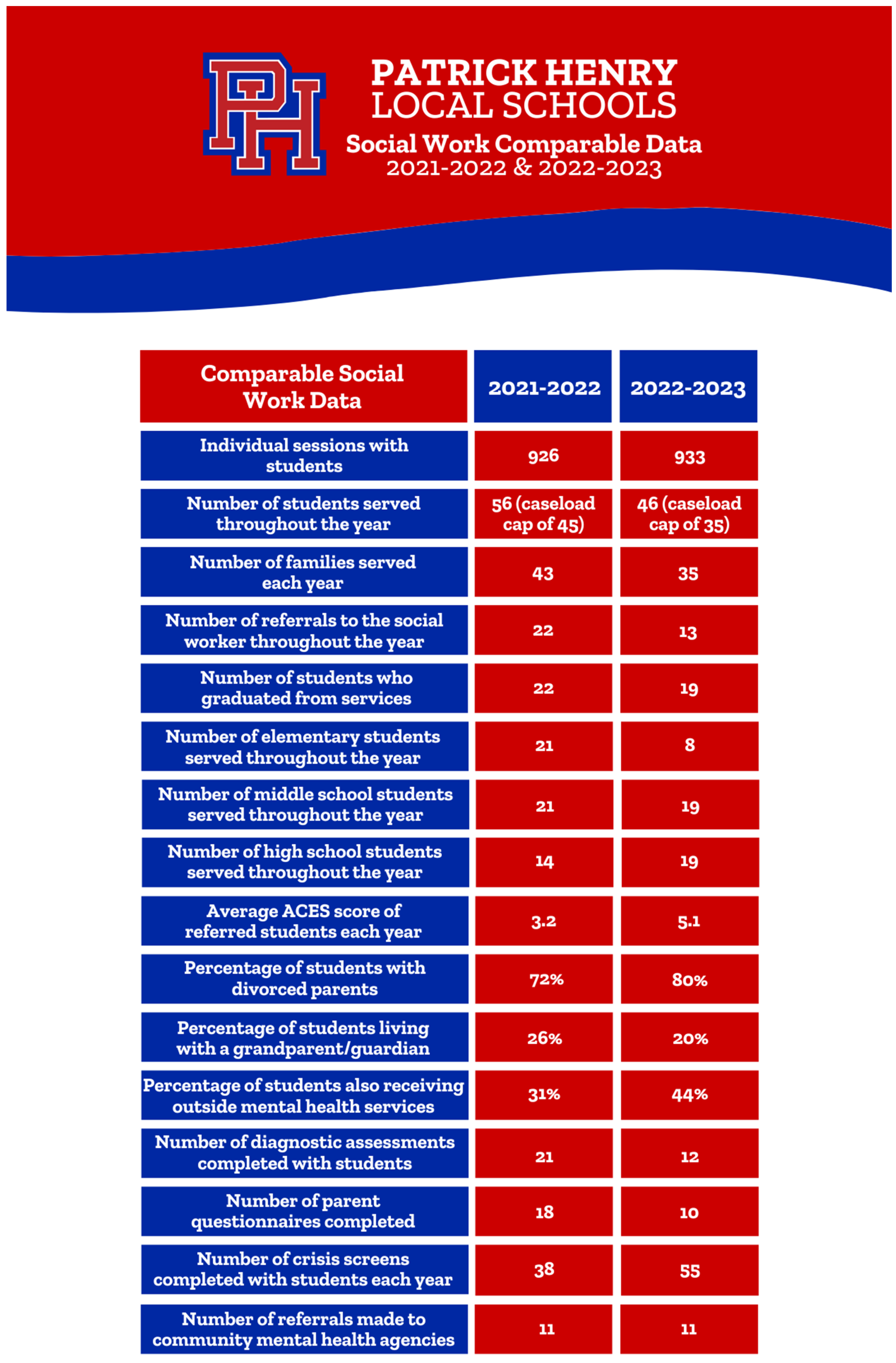

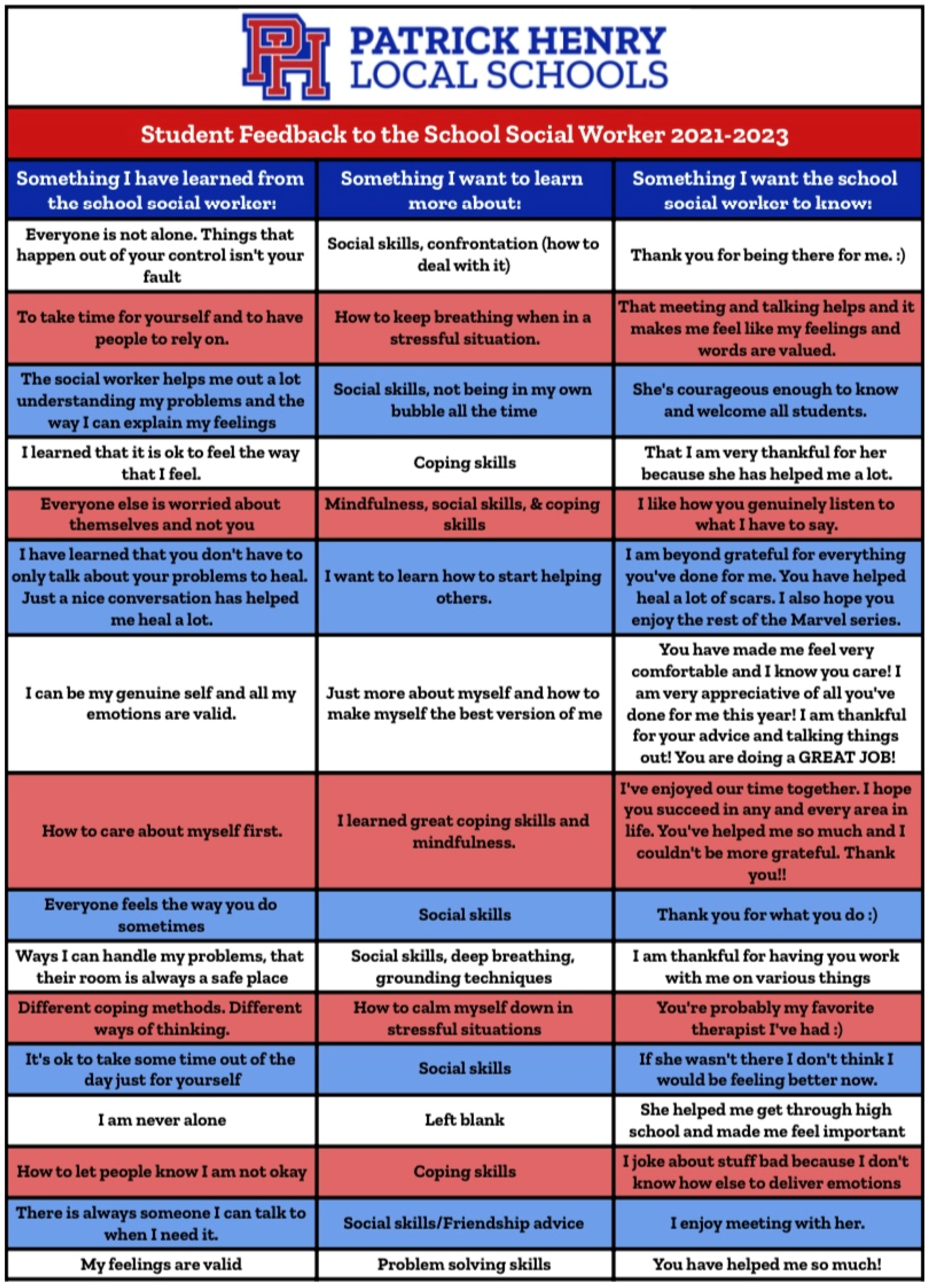

The district has collected and compared data over the course of two school years to evaluate the impact and receive feedback regarding the new Tier 3 service (see Figure A4 and Figure A5). To gain student feedback, at the end of each school year, students were asked a set of questions to allow the school social worker to understand the experiences students encountered when utilizing social work services. Student feedback was collected anonymously and derived from the following questions:

- “What is something you have learned from the school social worker?”

- “What is something you would like to learn more about?”

- “What is something you want the school social worker to know?”

Barriers and Next Steps

At Patrick Henry Middle School, the SAP process continues to be refined as the first full year of implementation has brought valuable insight on various issues. The SAT identified that the primary barrier was a lack of time to fully implement and monitor the interventions that were put into place in the classroom setting. For instance, teachers were not able to address the needs of the SAP students as frequently as planned due to various situations, such as schedule changes. Additionally, there was not enough time to meet with individual students to address their needs in order to help them meet their social-emotional goals. The team also determined that there was an overall lack of Tier 2 behavior interventions as well as an insufficient number of staff members to implement these supports. For instance, many students would have benefited from additional group support or one-on-one counseling, but short staffing hindered the district’s ability to provide these supports. However, the middle school continues to develop interventions and plans for progress monitoring using research-based interventions and data-driven models. For example, the middle school uses the ROX (Ruling Our Experiences) [15] program to provide data-driven supports for middle school girls who may be struggling with anxiety, body image, dating, self-esteem, and other concerns.

The middle school is also increasing opportunities for student leadership by designing activities such as peer-led projects to promote encouragement among students for positive behaviors. As Patrick Henry Local Schools continues to create a model that gives students more skills and abilities to assist in managing student behaviors, the hope is to better equip teachers to effectively allow an increase in leadership roles among their students and focus more efforts on student achievement.

Sustainability Consideration

The school district has been utilizing the federal grant funding, ESSER, to pay the salary of the school social worker. This funding ends during the 2023–2024 school year, meaning that the district will need to obtain funding through other avenues as a sustainment strategy to continue to employ a social worker and the additional supports that are currently in place [10]. The district remains committed to providing mental health services to students through the employment of a school social worker and has acknowledged that the cost of not having this position on site is much greater than the cost of employing someone directly. Going forward, the district has plans to utilize general fund dollars, if other funding sources are not available, to continue providing mental health resources to the students. The district has also been meticulous in finding resources that are both helpful for their students and sustainable in terms of ongoing funding. Hailemariam et al. [10] provide evidence that funding is both the second largest facilitating factor of implementation as well as the overall largest hindering factor of implementation. With this in mind, the district values its partnership with the Maumee Valley Guidance Center, which funds the evidence-based intervention program, Signs of Suicide. Additionally, the district utilizes Closegap, a free, evidence-based, social-emotional check-in platform, to allow continued access for future use.

Because the SAT and SAP processes take a considerable amount of time to implement with integrity and fidelity, it is important to establish routines that sustain staff buy-in [10]. At Patrick Henry Local Schools, teachers are included in the SAT and are able to witness, firsthand, the benefits of the team and the process of supporting the students. As a result of the interventions provided in the SAP, students reported to staff, through their responses in the universal screener given in the spring, that their social-emotional health improved. At the end of the SAP’s first year, staff members were asked to provide feedback and be a part of the ongoing process to guide the continuous improvement of the program. Additionally, staff use progress monitoring as a strategy to maintain sustainability within the program [10]. These progress monitoring strategies include follow-up meetings, revisiting student screener data, and anecdotal records shared by staff members who work daily with the students. The middle school plans to refine and enhance the SAP over time to support sustainability.

2.1.2. Equitable

Equitable practices attempt “to identify the specific needs of those within the group [but focus] on what is fair for the individual” [19]. Patrick Henry Local Schools is dedicated to equitable services for students, as demonstrated through the district’s mission statement to “create an environment where all students discover their personal best in every opportunity”. The equitable practices established throughout the district include training for staff on Youth Mental Health First Aid [20], opportunities to receive professional development, and tools for fostering appropriate learning environments for English Learning students. We will discuss each below.

Recently, a portion of staff members throughout the district completed training on Youth Mental Health First Aid (YMHFA) to enhance their knowledge regarding the mental health of students in the school community and how they can both identify and support students who struggle with their mental health. The district is committed to ensuring all staff have an opportunity to enhance their knowledge on how to best help students navigate social-emotional concerns. To ensure this is a reality, Patrick Henry Local Schools hopes to have additional staff receive the YMHFA training this school year. This programming is free for each staff member to attend due to the grant funding the Maumee Valley Guidance Center receives. Moreover, the high school has a newly formed Peer-to-Peer Guidance group that meets monthly to empower high schoolers to be leaders among their peers and help lessen the stigma associated with mental health. A goal for the group is to have these students also complete the Youth Mental Health First Aid training this year, which will allow students to better guide their struggling peers to the appropriate resources.

To support positive, student-centered, equitable, and fair approaches to behavior, school staff received professional development training on behavioral leadership practices. The district-wide training was provided by a consultant, Scott Ervin, in 2022, and the district continues to work with Scott Ervin’s behavioral leadership team to further enhance classroom management practices for the 2023–2024 school year. Meanwhile, the middle school has initiated training for staff and students on ways to incorporate student leadership into daily classroom management roles and routines. The training encourages and educates teachers on how to best use student leadership opportunities as strategies to encourage positive behaviors from their peers. The district aims for this training to support teachers in being able to recognize positive or negative behaviors and respond to them in a student-centered way while allowing students to be involved in the decision-making process to create a better learning environment for all.

Recently, the district identified a need for additional services on campus that foster an equitable learning environment. Over the past year, the district proportion of English Learners (EL) increased significantly from 0 EL students to 21 EL students. To provide appropriate instruction and meet the needs of the EL students, staff members have received support and training. This training helped provide staff with the tools to create an equitable learning environment for students by helping them access the day-to-day curriculum. Training included technical support to allow for content and language to be translated as well as ways to provide differentiated instruction to best meet the EL students’ needs. As the EL population has continued to grow within the community, the district has expanded services for the students who are identified as needing more support based on teacher recommendations and the Ohio English Language Proficiency Assessment [21] screener that is administered each spring. At the start of the 2023–2024 school year, the district employed a full-time tutor who works closely with classroom teachers to provide academic tutoring as well as support for the EL families within the community.

The district has also identified a need to provide additional support to the special education population. Students who receive special education services often struggle with coping mechanisms as well as need support with executive functioning and problem-solving. As a catalyst for the mental health team to begin providing additional support, students receiving special education services are asked about their self-esteem and self-perception. Students meet with the school counselor or are referred to the school social worker to enhance their ability to cope, problem-solve, and navigate not only their academic struggles but also peer relationships and family dynamics. To address the need for executive functioning, students were identified through the SAP process and placed into a small group to receive targeted support. The group meets weekly for six weeks to learn organization and time management skills. Meanwhile, staff work closely with the school counselor and social worker to communicate individual student needs and progress to efficiently and effectively provide the added support needed for student success.

Barriers and Next Steps

Patrick Henry has evaluated each method to identify lessons learned and guide the next steps for promoting equitable practices. The lack of time for staff training was identified as a recurring barrier. Staff members feel that additional programming may not be sustainable and take time away from instruction and the educational environment. As teachers need additional planning time to initiate the programming, they may struggle with emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment dimensions of burnout [22]. A study conducted by Smith et al. [23] reported that 41% of teachers disclose high levels of stress when compared to 26 other occupations. To overcome this barrier, the YMHFA training was offered over the summer in an effort to not take away valuable instructional time in the classroom during the school year. With behavioral leadership training provided, Patrick Henry Local Schools aims to organize resources that will reduce staff’s already overflowing workload and allow them to focus more on the lessons taught than on management or discipline issues.

Sustainability Consideration

Patrick Henry Local Schools is planning ongoing training of current and new staff as a sustainability strategy to support faculty and staff in using equitable behavioral practices [10]. To allow new staff to develop and utilize the same behavioral leadership skills in the classroom, the district plans to continue the relationship with Scott Ervin. This will provide new staff members with the training that existing staff have received in the past to maintain the integrity of consistent classroom, building, and management techniques. Similarly, high school students at Patrick Henry will continue to work in the Peer-to-Peer Guidance group with hopes of taking on student leadership roles to promote positive behaviors and guide struggling students to appropriate supports to embed these practices in the district culture. This relates to the continued training, supervision, and feedback sustainability strategy that was identified in Hailemariam et al.’s [10] review.

The district also uses a continuous improvement process to evaluate programs, increase continued compatibility within the district and practices, and identify areas for improvement when developing future opportunities [10]. For example, specific staff members were identified and trained by Scott Ervin’s behavioral leadership team to be “coaches” for their fellow colleagues, allowing for valuable conversations in addition to feedback on the effectiveness of the program and ways to make the techniques and trainings work at an individual level. To provide staff with the opportunity to share feedback after completing the YMHFA training, staff members were asked to complete a Google form to identify the necessary changes that would improve future training sessions for new staff. The data collected from this survey were used to plan upcoming opportunities for staff to receive training and guide sustainable district policies and practices. Meanwhile, with the addition of each layer of support, the Patrick Henry administrative team has been intentional with prioritizing and supporting the continued use of equitable practices by walking staff members through what each platform or program would look like and what involvement or role staff would have to play in the implementation process, which relates to the strategy of organizational leaders prioritizing and supporting continued use [10].

As the district seeks sustainable practices for the future of EL learners, there is uncertainty surrounding the future of the community’s EL population. Regardless of whether families become transient and move out of the area or establish roots within the community, the district will continue their partnership with the EL tutor as well as continue to explore other opportunities that best support the needs of the EL students and families. Currently, the district creates individual, academic EL plans for the students to determine and provide appropriate supports at school. Additionally, district representatives have spent time with the EL families to develop relationships and connect families to necessary resources within the community. As Shim [24] recommends, the district will continue to foster these partnerships to assist in improving the overall wellness of the EL students.

With limited resources and additional services needed for students who require support beyond the school day, finding ways to support the special education population is ongoing. While the search for additional resources is never-ending, the district will continue identifying and providing one-on-one or small group meetings for special education students through the SAP process.

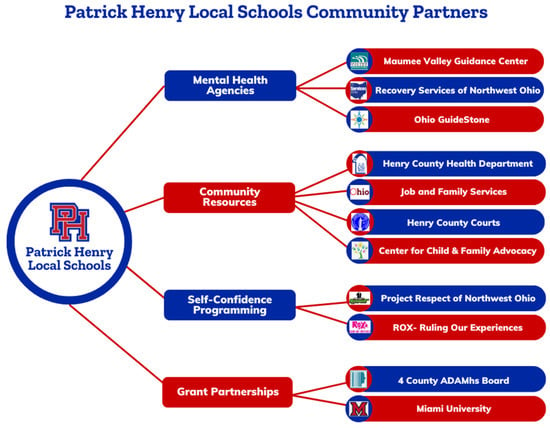

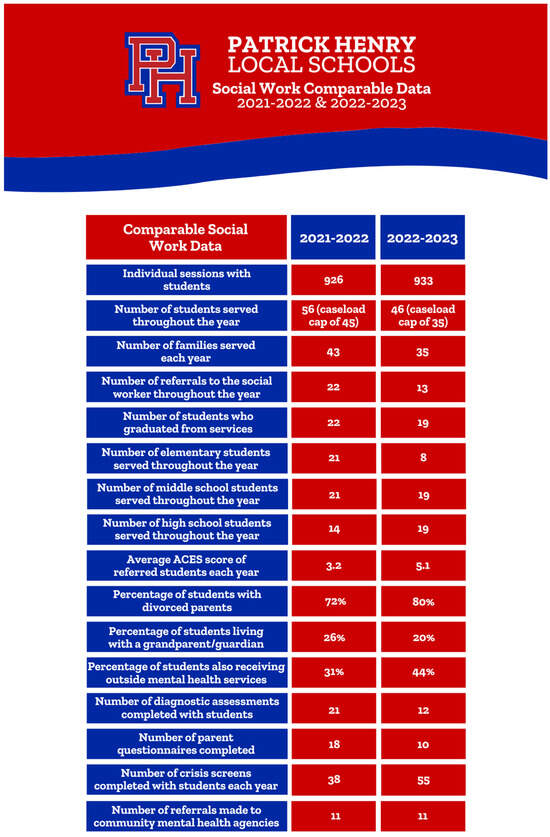

2.1.3. Collaborative

Patrick Henry Local Schools formed many partnerships within their community to bring valuable resources and educational opportunities directly to their students through mental health agencies, community resources, and self-confidence programming (see Figure A3). Furthermore, the district formed funding partnerships with Miami University and the Four County Alcohol, Drug Addiction, and Mental Health Services Board to support district wellness goals. Krumm & Curry [25] stress the importance of schools creating partnerships with service organizations to meet all the needs of their students. For several years, Maumee Valley Guidance Center has partnered with Patrick Henry to provide the Signs of Suicide [12] programing for students in grades 6–12. As part of the SOS Programming, a licensed clinician from their agency screened each student for depression. Students deemed “at-risk” then meet with the school counselor or the school social worker to provide the student and their parents/guardians with suggestions and resources to appropriately address the student’s mental health needs. Furthermore, the school social worker developed a relationship with Recovery Services of Northwest Ohio to address the need for additional, out-of-district mental health services for students. This partnership allowed for services, such as meetings with a psychiatrist, to be more accessible to students in need.

To further meet students’ wellness needs and collaboratively enhance preventative services, Patrick Henry Local Schools added the position of Behavioral Health and Wellness Coordinator in the 2022–2023 school year. This position is employed directly by the district and is funded through a grant the district received from Miami University and the Project AWARE (Advancing Wellness and Resiliency in Education) grant. Through this additional support, the district planned a “Value-Up Day” for students in grades 5–12. The event was hosted on campus, where students heard from speaker Mike Donahue about the intrinsic value students hold within themselves. That day, students also received education on various mental health topics, such as healthy coping skills and the relationship between their physical and mental health. During the 2023–2024 school year, the local health department worked with Patrick Henry Local Schools to host an event that aims to reach 6th–12th grade students who are self-medicating with phones, gaming, eating, vaping, drinking, substance use, and other risky behaviors. The event was part of the Get Schooled Tour through the RemedyLIVE agency [26] and was funded by grants the local health department received. Students attended the program during their school day, and in the evening, parents/guardians and community members were invited to attend the event on the Patrick Henry campus to obtain information on these topics and learn how parents, themselves, can best help their students manage and effectively cope with mental health struggles. By developing partnerships with community organizations, Patrick Henry has implemented vital programming to address the needs of their students. This approach allows the district and community agencies to work together and create opportunities for programming that benefit students, families, and the overall community.

Prior to these extensive partnerships being built, school counselors provided guidance lessons and referred students to local community agencies as needed. While students were receiving out-of-district support from various agencies, the school counselors would also meet with the students as needed to provide them and their families with additional support. A previous partnership with an outside mental health agency that began in 2017 was used to provide students with therapy services. This partnership dissolved in 2021 as the needs of the district were greater than the agency could support, prompting the district to move forward with the internal hiring of a school social worker to better meet the needs of the student population.

To form the partnerships listed in Figure A3, staff members on the mental health team reached out to and met with the agencies to discuss the needs of students and the programs available to address these issues. Additional partnerships have been formed by networking and building relationships at mental health work-group meetings through the local health department (e.g., Habitat for Humanity, Henry County Cares Program, Henry County Family and Children First Council, etc.). Through providing students and families with resources from these external agencies, student needs are more easily addressed, and students receive the needed support.

Barriers and Next Steps

Patrick Henry is dedicated to the partnerships with each entity shown in Figure A3 and will continue to work closely with each group by allocating resources, fostering relationships, partnering with local agencies, and utilizing grant partnerships to ensure students have access to these resources for years to come. With the increase in demands for mental health supports, it is often difficult to schedule programming that works with an agency’s availability and minimizes disruption to the academic portion of the school day. Programming opportunities are limited as the few local agencies that are available serve the entire county, and the district’s location within the county often leads to these resources being out of reach. While outside agencies maintain efforts to address staffing concerns as well as the limited access to resources, the district continues to accommodate the scheduling needs for programming to ensure students receive essential supports.

A goal for the 2023–2024 school year is to enhance parent/guardian and community awareness of the concerns that are currently impacting students. Patrick Henry Local Schools hopes to achieve this goal through the event held in October 2023, which was offered to the community in collaboration with the local health department. To evaluate the impact of this event, data were collected from the students and community members during each event. This data will be used to determine the impact of the event and help plan for future programming.

Sustainability Consideration

The use of community partnerships helped ensure that the district has the necessary funding and resources to continue to offer these opportunities to staff and students in the future, which relates to not only the overall funding strategy for sustainability but also the access to new and existing money to facilitate sustainment [10]. Patrick Henry uses a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to maintain the establishment and implementation of their mental health resources for continued use. Efforts of public collaboration to attend community work-group meetings are used to sustain relationships with various mental health agencies. Meanwhile, services are contracted through the Four County Alcohol, Drug Addiction, and Mental Health Services (ADAMhs) Board to help allocate funding for the employment of the Behavioral Health and Wellness Coordinator. The continued emphasis on funding is critical to sustaining collaborative partnerships [9,11].

3. Results

Based on this case example of one district’s efforts to plan for sustainability within systematic, equitable, and collaborative approaches, school districts should first start by identifying their district’s specific student needs. After the needs have been identified and narrowed, schools can create a team to plan methods to match the needs of the students. Correspondingly, schools should develop a plan for funding, training, sustainment, and program evaluation strategies before implementation [7]. The team can then start the design of a universal program to address the Tier 1 needs of all students. Before the program is implemented, appropriate training should be administered to all faculty and staff. The team should also create a plan and decision-making process for Tier 2 and Tier 3 interventions. To further enhance the success of this practice, the team can generate community involvement efforts such as networking and building relationships, as well as informational events and pamphlets to increase awareness of effective coping and management strategies regarding the mental health struggles of the community’s youth. Based on Scheirer’s [8] systematic review of sustainability, new programs should be modifiable, the district should identify initiative champions, planning teams should consider how new programs and initiatives fit with the district’s mission and processes, leadership and planning teams should highlight benefits to staff and students, and districts should collaborate with stakeholders in community agencies to provide support. Further, planning for ongoing funding is critical, as it is one of the primary influencing factors for sustainability [10]. Hoover et al. [11] describe the importance of diverse and leveraged funding when planning school mental health systems and the need to continuously monitor new funding opportunities.

4. Discussion

Patrick Henry Local Schools used the four guiding principles of systematic, collaborative, equitable, and sustainable efforts to efficiently and effectively support wellness for their students and staff. The district uses a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS), universal screening tools, data-driven decisions, and progress monitoring to document service and support outcomes. Specifically, prevention programming, Closegap, SAP and SAT, and other more intensive supports are used systematically to support and address the social-emotional needs of students. Youth Mental Health First Aid trainings, student leadership roles, and English Learner supports (e.g., EL tutor, EL learning plans, and family-school collaboration) provide equitable practices for each student. At the same time, collaborative efforts are accomplished through community partnerships, where networking and building relationships at local mental health workgroup meetings provide students and families with resources from external agencies.

Without sustainability practices, these initiatives and supports are not feasible and would fade over time. Patrick Henry Local Schools has established sustainable efforts by addressing the need for future funding as the ESSER grant comes to an end during the 2023–2024 school year. Previous research [9] and best practice guidance [11] note the need to attend to funding when planning mental health initiatives, and this relates to the funding for a continued use sustainability strategy [10]. To address resource barriers to sustainability [9], the district employed a school social worker to provide on-site supports, collaborated with local organizations for evidence-based intervention programs, and utilized the free, online check-in platform, Closegap. To promote the maintenance of staff buy-in [10], teachers are included in the SAT to assist in developing appropriate procedures to continuously improve the program while also evaluating student screener data and anecdotal records to monitor the progress of each student.

To continue providing these services with fidelity, the leadership staff has taken the initiative to maintain the integrity of the services through the involvement of observational feedback, modeling, and district trainings [10]. The district intends to continue employing the EL tutor, evaluate and modify student EL plans, and connect EL families with community resources in order to improve the overall wellbeing of the student and their family. Similarly, community partnerships have been sustained through relationships and contracting efforts [10].

The current case example describes sustainability strategies related to one district’s school mental health continuum of support. However, additional research is needed to monitor the impact of these identified sustainability strategies (e.g., funding, staff buy-in, progress monitoring, trainings, prioritizing equitable practices, networking, and community events) on school mental health practices. Specifically, Scheirer [8] discusses the limited research on the longevity of grant-funded programs. Researchers should evaluate the effects at the conclusion of funding regarding program implementation to discover the probability in which program components remain active. Future research should also evaluate how locally developed universal screening tools impact implementation, acceptability, data use, and sustainability of screening practices compared to standardized tools developed by test publishers. In addition, the education and social-emotional health of EL students in rural districts should be studied further to provide practitioners with research-based implementation strategies. While this article presents an example of one rural school district of several small communities united together, further research is needed within larger and more diverse populations to evaluate the effects of sustainable, systematic, equitable, and collaborative methods. Regarding collaborative efforts, Aarons et al. [27] suggest the implementation of a Community Development Team (CDT) to remove and delegate staff responsibilities that are needed to ensure proper program performance. This team, however, would require additional research to evaluate the impact it might have on the sustainability of collaborative and systematic practices.

5. Conclusions

With the increased and intensified social-emotional needs of students since the COVID-19 pandemic, Patrick Henry Local Schools has utilized ESSER funding from the U.S. Department of Education [5] to establish new initiatives and support for students experiencing mental health struggles. These initiatives and supports include hiring a school social worker, a multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) framework, implementing universal screening tools for early identification and intervention, using data-driven decision-making, and incorporating progress monitoring efforts to document the impact of services and supports that have been provided to their students. Patrick Henry Local Schools district continues to use four guiding principles—systematic, equitable, collaborative, and sustainable approaches to efficiently and effectively support wellness for all students and staff. These guiding principles ensure that programs remain structured, data-driven, efficient, fair, and consistent over time. Given the importance of promoting a continuum of innovative mental health supports outlined in the case example above, it is critical for schools to embed sustainability efforts to ensure all students have access to effective practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.V.D.; resources, M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, K.V.D. and K.A.; writing—review and editing, M.D.; visualization, K.V.D., K.A. and M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. Funding the school had previously received is discussed within the article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support given to them by the Patrick Henry Local Schools Superintendent, Josh Biederstedt. They acknowledge all of the individuals and groups who contributed to the OSWI project (e.g., the pilot schools, Ohio Department of Education, Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, and Miami University, the Ohio School-Based Center of Excellence for Prevention and Early Intervention), as well as the funding that supported it from the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief (GEER) funds under Ohio’s share of Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) funds. The authors also acknowledge Kristy Brann for her editorial assistance on this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The views in this paper do not necessarily represent those of any of the funding or collaborating organizations. The name of the school district is included with permission from the district Superintendent.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Academic, Behavioral, and Emotional Tiered Systems of Support. The colors in this diagram reflect district branding and do not represent meaning beyond the district level color scheme.

Figure A1.

Academic, Behavioral, and Emotional Tiered Systems of Support. The colors in this diagram reflect district branding and do not represent meaning beyond the district level color scheme.

Figure A2.

Patrick Henry Middle School SAP Flow Chart. The colors in this diagram reflect district branding and do not represent meaning beyond the district level color scheme.

Figure A2.

Patrick Henry Middle School SAP Flow Chart. The colors in this diagram reflect district branding and do not represent meaning beyond the district level color scheme.

Figure A3.

Patrick Henry Local Schools Community Partners. The colors in this diagram reflect district branding and do not represent meaning beyond the district level color scheme.

Figure A3.

Patrick Henry Local Schools Community Partners. The colors in this diagram reflect district branding and do not represent meaning beyond the district level color scheme.

Figure A4.

Patrick Henry Local Schools Social Work Comparable Data. The colors in this chart reflect district branding and do not represent meaning beyond the district level color scheme.

Figure A4.

Patrick Henry Local Schools Social Work Comparable Data. The colors in this chart reflect district branding and do not represent meaning beyond the district level color scheme.

Figure A5.

Patrick Henry Local Schools Student Feedback to the School Social Worker 2021–2023. The colors in this chart reflect district branding and do not represent meaning beyond the district level color scheme.

Figure A5.

Patrick Henry Local Schools Student Feedback to the School Social Worker 2021–2023. The colors in this chart reflect district branding and do not represent meaning beyond the district level color scheme.

References

- Whitney, D.G.; Peterson, M.D. US national and state-level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.S.; Berglund, P.A.; Olfson, M.; Kessler, R.C. Delays in initial treatment contact after first onset of a mental disorder. Health Serv. Res. 2004, 39, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elharake, J.A.; Akbar, F.; Malik, A.A.; Gilliam, W.; Omer, S.B. Mental health impact of COVID-19 among children and college students: A systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2023, 54, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Department of Education. State Plan for the American Rescue Plan Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund. Available online: https://oese.ed.gov/files/2022/07/OH-ARP-ESSER-Plan-Redacted-1.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohio School Wellness Initiative (OSWI). Ohio Student Assistance Program Manual. Ohio School Wellness Initiative. Available online: https://www.ohioschoolwellnessinitiative.com/sap-manual (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Scheirer, M.A. Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. Am. J. Eval. 2005, 26, 320–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, A.; Stapley, E.; Hayes, D.; Town, R.; Deighton, J. Barriers and facilitators to sustaining school-based mental health and wellbeing interventions: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hailemariam, M.; Bustos, T.; Montgomery, B.; Barajas, R.; Evans, L.B.; Drahota, A. Evidence-based intervention sustainability strategies: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoover, S.; Lever, N.; Sachdev, N.; Bravo, N.; Schlitt, J.; Acosta Price, O.; Sheriff, L.; Cashman, J. Advancing Comprehensive School Mental Health: Guidance from the Field. National Center for School Mental Health. University of Maryland School of Medicine. 2019. Available online: https://www.schoolmentalhealth.org/media/som/microsites/ncsmh/documents/bainum/Advancing-CSMHS_September-2019.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Aseltine, R.H., Jr.; DeMartino, R. An outcome evaluation of the SOS suicide prevention program. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Project Respect NWO. (n.d). Project Respect. Available online: https://projectrespectnwo.org/ (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- Foshee, V.A.; Bauman, K.E.; Arriaga, X.B.; Helms, R.W.; Koch, G.G.; Linder, G.F. An evaluation of Safe Dates: An adolescent dating violence prevention program. Am. J. Public Health 1998, 88, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinkelman, L. Girls without Limits: Helping Girls Succeed in Relationships, Academics, Careers, and Life, 2nd ed.; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sandy Hook Promise. (n.d.). Start with Hello. Available online: https://www.sandyhookpromise.org/our-programs/start-with-hello (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- The Women’s Center of Tarrant County. Play it Safe! 2020. Available online: https://www.playitsafe.com (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Miller, R. Closegap. 2017. Available online: https://www.closegap.org/ (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Ramirez, T.; Brush, K.; Raisch, N.; Bailey, R.; Jones, S.M. Equity in social emotional learning programs: A content analysis of equitable practices in preK-5 SEL programs. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 679467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakre, J.M.; Lucksted, A.; Browning-McNee, L.A. Evaluation of Youth Mental Health First Aid USA: A program to as-sist young people in psychological distress. Psychol. Serv. 2016, 13, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohio Department of Education and Workforce. (n.d.). Ohio English Language Proficiency Screener (OELPS). Available online: https://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Testing/Ohio-English-Language-Proficiency-Screener-OELPS (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Schwab, R.L. Maslach Burnout Inventory, 2nd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Brice, C.; Collins, A.; Mathews, V.; McNamara, R. The scale of occupational stress: A further analysis of the impact of demographic factors and type of job. Cardiff Health Saf. Exec. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, J.M. Involving the parents of English language learners in a rural area: Focus on the dynamics of teacher-parent interactions. Rural Educ. 2013, 34, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumm, B.L.; Curry, K. Traversing school–community partnerships utilizing cross-boundary leadership. Sch. Community J. 2017, 27, 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Faupel, C. Get Schooled Tour. RemedyLIVE. 2006. Available online: https://www.getschooledtour.com/ (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- Aarons, G.A.; Hurlburt, M.; Horwitz, S.M. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2011, 38, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).