Abstract

The approach to the personal experiences and previous ideas about physical education of future primary education teachers is a starting point of great interest for the teaching of the subject of physical education didactics. The aim of the study is to investigate these prior beliefs and to verify to what extent this initial perception changes after taking the “Didactics of Physical Education” course. A concurrent mixed-methods study was conducted, which included two data collection procedures: (1) a pre-experimental design with a single group featuring a pre-test and post-test; (2) the analysis of students’ autobiographical accounts of their experiences with physical education in school. The participants were students enrolled in the Bachelor’s degree program in primary education at the University of Santiago de Compostela (USC) who undertook the course in 2022–2023. The results obtained reveal that after taking the Didactics of Physical Education course, students gave greater value to more positive concepts of learning, socializing, participating, and playing, among others. Similarly, in the post-test, the assessment of concepts such as competitiveness and physical fatigue diminished. In their autobiographical accounts, students associated good memories with relationships with classmates and the playful socializing nature of the subject; among the bad memories, they highlight the content related to physical performance, competitiveness, and lack of attention to the diversity of students and their individual characteristics.

1. Introduction

The main objective of pre-service teacher education is to train students to act as teachers when they start working at schools [1]. Teacher training programs offer content and skills that will enable future teachers to respond to the challenges they will necessarily face in real teaching contexts [2]. The current teaching degree program in our university is composed of four modules; the first module is foundations in education, with 60 ECTS credits (sociology, psychology, family, childhood, community, school management and curriculum design). The second module (120 credits in total) is related to pedagogical content about the subjects in primary education (Sciences, Languages, Mathematics, Art, Music, and Physical Education, where the “Didactics of Physical Education” course is located). The third module is related to school placement and a final degree project (52 credits ECTS), and the fourth module is composed of optional credits. The final amount is 240 credits.

The “Didactics of Physical Education” course in our program is focused on the curriculum and methodology for teaching PE in primary schools by generalist primary education teachers. The course’s structure is composed of lectures and practical lessons in which the concepts and ideas about PE and the applications for the teaching practice are studied. Also, the official curriculum of primary physical education is investigated and implemented, reflecting and drawing conclusions from the observations and practices carried out. It is taken in the second semester of the second year (6 ECTS credits) and is compulsory for all undergraduate students in primary education. The intention is to give future primary teachers a general comprehension of what PE is and how it will be implemented in schools. It is therefore important to focus attention on the contents of teacher training programs, the competences that they contribute to developing, and their orientations and philosophy, to help future teachers engage in a process of critical thinking on what they are learning, how they acquire this knowledge, and how they can make it accessible to their learners [3]. It is based on the idea that learning is a process of active knowledge construction [4], where graduates from education programs have an important background of experiences, drawn from their many years as learners, which make up their educational biography [5,6], and which influences the way they interpret and process new information. These ideas possess great interpretative value and constitute the supporting framework on which their future learning is based, facilitating or preventing it. All students’ teachers will bring some experiences to the table, and allowing them to talk about and share their impressions, and try to deconstruct some of the practices they lived, is a powerful tool for reflection.

Coe, Aloisi, Higgins, and Elliot Major [7] identified six components of great teaching: pedagogical content knowledge, quality of instruction, classroom climate, classroom management, professional behaviors, and teachers’ beliefs. Richardson [8] reminds us that students who enter initial teacher education (ITE) programs do so with beliefs about teaching and learning which serve to filter their learning and their interpretation of new knowledge. These beliefs are formed through their apprenticeship of observation [5] from personal experiences, knowledge, and school experiences as pupils. Additionally, Feiman-Nemser [9] suggests that prospective teachers are often unaware of how their beliefs influence the way they learn and acquire new knowledge. It is important to underline that such beliefs affect what and how they learn in initial teacher programs, by acting as a filter through which they view their educational experiences. Some authors have already insisted on the need to understand how these beliefs are formed from a very early age and how they can be conditioned, among other aspects, by what future teachers consider good teaching [10,11]. The issues they deal with have to do with pre-service teachers’ perceptions of how they were taught, memories of good and bad teachers, the complexity of the teaching–learning process, or the influence of school on their choice of a teaching vocation [12]. Others, such Capel et al. [13], demonstrate that some previous sports experiences influence the value students’ teachers placed on PE lessons. If pre-service teachers’ beliefs about learning PE are not addressed, there is a risk that ITE programs will fail to promote a comprehensive understanding of teaching and learning. Moreover, Chróinin and O’Sullivan [14] employ reflective writing tasks for elementary classroom teachers, both in initial training and the induction period, as a tool to map their beliefs. Therefore, we consider it important to know the prior concepts [15,16,17] and beliefs regarding school, teaching–learning processes, and physical education that prospective teachers bring with them [14,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. A deeper understanding of future teachers’ beliefs about learning to teach PE is needed to inform the ITE program. These intuitive, generic ideas, drawn from their personal experiences, are resistant to change, and act, if they are not explicitly and adequately addressed, as retaining dikes for initial training [29]. We believe that our role as teacher educators is to attempt to modify the teaching approaches that our students bring with them. As Carter [30] remind us, the strength of a teacher educator is in their ability to deconstruct their own and others’ practices to demonstrate what effective learning and teaching are.

We used a concurrent mixed-methods study, involving quantitative and qualitative data collection. For the qualitative data, we employed a narrative inquiry, which provided us with important insights into teaching and learning. As Clandinin and Connelly [31] point out, narrative inquiry is a way of understanding experience. Casey et al. [32] discuss narrative inquiry as a way of understanding experience in relationship to the researchers’ experiences, the participants’ experiences, and the social context. It gives a voice to the teachers’ participants, helping to draw connections between their practice, the context, and their lives [33]. While this line of research is not mainstream in physical education [34,35], it allows for a deeper understanding of the beliefs and assumptions that our students bring with them. When people tell, re-tell, and re-live their experiences, they contextualize biographical information and embodied knowledge [36], revealing what, and importantly, how they have learned in the past, which helps to direct future learning. This line of autobiographical and life history research [37,38] has also made important advances in the construction of the teaching identity of physical education teachers [39,40,41,42,43].

This work is part of a broader research project developed within the framework of the Didactics of Physical Education course, which uses autobiographical accounts of students who are working toward a degree in primary education related to their experiences with physical education [44]. Its aim is to investigate to what extent the students’ perception of the objectives and components of physical education change after taking the “Didactics of Physical Education” course for their degree in primary education at the University of Santiago de Compostela (USC). To do so, we compare students’ previous assessments of physical education based on their personal experiences and beliefs, with their subsequent assessments once they have taken the course. Three main objectives were established:

- -

- To inquire about students’ experiences with physical education during their school trajectory through the autobiographical analysis of their best and worst memories.

- -

- To find out the beliefs and previous concepts on physical education that students, future primary teachers, bring with them.

- -

- To compare the students’ perceptions of the components of physical education didactics before and after taking the “Didactics of Physical Education” course.

The use of a concurrent mixed-methods study to investigate the beliefs and perceptions of future teachers, combining quantitative and qualitative data, adds a new and distinctive dimension, as the literature has rarely captured these perspectives. Both approaches complement and expand our vision of what physical education pedagogy is and means for future teachers.

2. Materials and Methods

A concurrent mixed-methods study was conducted, involving the simultaneous collection of both quantitative and qualitative data [45]. The use of the mixed-methods approach entails a systematic set of research processes and includes the simultaneous collection of quantitative and qualitative data, followed by their integration and joint discussion to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the studied phenomenon [46]. The selection of this method aligns with the formulated research objectives and allows for a more holistic response, enhancing the explanatory capacity of the results. Specifically, the combination of both methods will enable us to compare students’ perceptions of the content of the subject of physical education before and after completing the course. Additionally, it will enrich the significance of these results with students’ narratives about their experience with physical education throughout their school trajectory. The study was conducted within the framework of the Didactics of Physical Education course in the primary education degree program at the University of Santiago de Compostela (Galicia, Spain).

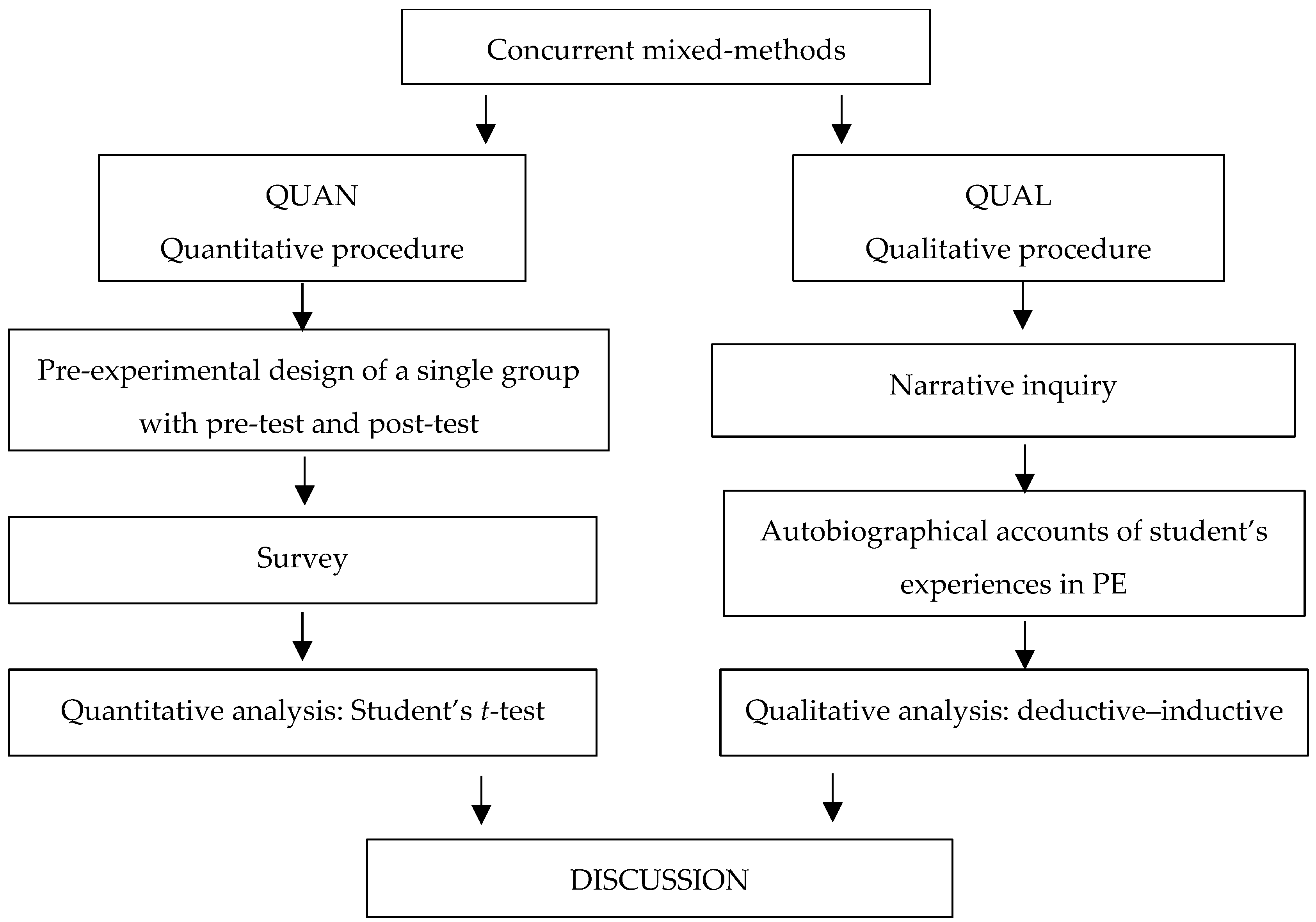

The research design followed methodological recommendations on mixed methods [45,47,48,49]. The subsequent description outlines the process followed and identifies the two approaches (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Method.

2.1. Quantitative Procedure (QUAN)

A pre-experimental design of a single group with a pre-test and post-test was carried out. There are three differentiated moments of the study that can be highlighted: (1) the application of the pre-test during the first week of classes (1st week of February); (2) the development of the ‘Didactics of Physical Education’ subject (February, March, April, and the 1st and 2nd weeks of May); and (3) the application of the post-test during the last week of classes (2nd week of May).

The instrument used was an ad hoc questionnaire comprising three content blocks: identification data, previous concepts and beliefs about physical education, and competences developed during the Didactics of Physical Education course. The configuration of questions in blocks 2 and 3 follows a Likert-type format, with a response scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much), for participants to assess their degree of agreement with different concepts and considerations about physical education and teaching physical education.

For its development, we took into consideration the results from previous research on students’ autobiographical accounts, the characteristics that define physical education didactics, and the methodological recommendations for making a data collection instrument of this nature provided by different authors [50,51,52]. Prior to its implementation, the instrument was revised by two experts in the development of research instruments in education and two specialists in the area of physical education didactics. The observations of this group of experts were considered for the final development of the data collection instrument.

2.2. Qualitative Procedure (QUAL)

The narrative method was employed through the analysis of students’ accounts of their personal experiences with the subject of physical education. To achieve this, students were asked, during the first week of classes (1st week of February), to provide a brief narrative about their best and worst memories related to physical education during primary education. The utilization of this method was grounded in the significance of narratives and the narrative method for comprehending and expressing students’ previous educational experiences [53,54]. It aimed to explore how these experiences shape their beliefs regarding education in a specific subject; in this case, the subject was physical education. The narrative method enables the understanding of the sequence of events and situations involving thoughts, feelings, emotions, and interactions, as recounted by those who experienced them [45].

2.3. Participants

The participant sample was selected using a non-probabilistic convenience sampling method [45,51,55,56], as it consisted of subjects who were accessible within the context of the Didactics of Physical Education course in the primary education degree program at USC. All participants were asked for their voluntary participation and were informed about the objective of the research.

A total of 59 students took part. A total of 78% were women and 22% were men. Most students were 19 years old on average (49.2%), followed by 20 (35.6%), and 21 (6.8%). Only 8.4% of the respondents were over 22 years old. Most of them indicated that they have participated in sports or extracurricular activities related to physical education (89.4%) and considered that this experience will influence their future work as teachers (81.8%).

2.4. Information Analysis

(1) Quantitative analysis: The quantitative analysis of information was performed using the statistical package SPSS version 28.9. This consisted in both a descriptive analysis (frequencies, media, standard deviation) and a comparative analysis to compare the results obtained on the pre-test and the post-test (Student’s t-test).

(2) Qualitative analysis: Similarly, a qualitative analysis of the students’ narratives was conducted, employing an inductive procedure where categories emerged from the reading, organization of information, and analysis of the meanings within the narratives [51]. The following is a summary of the procedure followed:

- -

- Each student is identified with a specific code (S1, S2, S3… SX), and their responses are presented exactly as described by them.

- -

- A first reading of the narratives was conducted to gain an overview of the scope of the themes that could be derived from the analysis.

- -

- The identification of the units of analysis was conducted, which is understood as segments of meaning in which each of the participants’ narratives is fragmented [45].

- -

- Coding process: the identification of themes and analysis categories. In this process, two initial analysis categories were considered: (1) positive experiences and (2) negative experiences, around which various subcategories emerged. Each of these subcategories was assigned a code. An example is as follows: the influence of the teaching role on a satisfaction level (TR); comparison with other subjects (CS). Subsequently, the classification of the units of analysis was carried out based on the identified subcategories.

- -

- The synthesis and interpretation of the meanings that emerge from the narratives was performed, considering the relationships established between the different analysis categories.

3. Results

The presentation of the results is based on the triangulation and complementarity of QUAN-QUAL results. To achieve this, one of the common procedures for presenting results in mixed-methods studies has been followed [56]. Specifically, we first present the quantitative statistical results regarding a topic, followed by qualitative results in the form of quotes related to the same topic. We specify how the qualitative quotes either confirm, disconfirm, or complement the quantitative results [56].

3.1. Beliefs and Previous Concepts about Physical Education

One of the key aims in our study was to find out students’ beliefs and previous concepts about physical education. The items to be assessed by students (Table 1) include both concepts that have traditionally been associated with physical education and others that respond to more innovative models in the teaching of physical education.

Table 1.

Pre-test and post-test comparison about key concepts related to physical education.

After applying the Student’s t-test, we found that there are statistically significant differences between the means obtained for all the concepts when comparing students’ personal experiences with the subject of physical education (pre-test) with their perception of the level at which they consider these concepts to be present once they had taken the course (post-test) (p < 0.01 for most of the concepts).

More specifically, the perception of students after taking the course (post-test) improves in relation to more innovative and positive physical education didactics, such as learning, participation, socializing, fun, and play.

These concepts are the ones that students valued most in their experiences of physical education during primary education. Indeed, in the analysis of students’ narratives about their experiences in physical education, the majority associate their “positive memories” with the playful nature of the subject, emphasizing its connection to periods of fun and enjoyment through games.

“I have very fond memories; I couldn’t highlight any in particular. I remember having a great time in almost every session, mostly when we played dodgeball; I loved that game. Also, I remember that during Halloween, the physical education department organized outdoor games that were very entertaining and enjoyed by everyone”(S10).

“How much fun I had during the sessions with my classmates, especially in the primary education stage; I have better memories because the teacher organized very fun games…”(S12).

“The best stage in physical education for me was in primary school. We played entertaining and fun games while learning at the same time”(S27).

On the contrary, in the post-test, the evaluation of concepts such as competitivity and physical fatigue decreases (Table 1). These “more negative” concepts such as competitiveness are also present when asked about their “negative memories”. The participating students mostly link them to experiences related to physical and endurance tests, especially in the later years. Similarly, some of the studied narratives point to the competitiveness that arose in certain moments in class, generally linked to the development of these physical tests.

“The worst memory I have of physical education could be the physical endurance tests, like the Cooper test, which I never saw any usefulness in since many people struggled with it”(S25).

“… comparisons between classmates, competitiveness, or activities related to performance in physical tests”(S8).

3.2. Characteristics and Purpose of Physical Education Didactics

A set of items on the concept, characteristics, and purpose of physical education didactics were also considered with the aim of comparing students’ previous ideas derived from their personal experience (pre-test) with their perception of these same items once they had taken the Didactics of Physical Education course for their degree in primary education (post-test) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pre-test and post-test comparison about the characteristics that define the didactics of physical education (Student’s test).

A first descriptive analysis of the data shows that, in the post-test, the results exceed a score of 4 (somewhat agree to strongly agree) in all items. Thus, most students highlight, above other aspects, the fun and motivating component of physical education, indicating that this is a way of learning while having fun and that it facilitates states of enjoyment and pleasure. Likewise, they highlight its importance in favoring social interaction and participation with others.

According to the results obtained with the Student’s t-test on the comparison between the pre-test and post-test, statistically significant differences were found in all the items. In eight of these items, this significance is p < 0.01, while in two of them, it is p < 0.05. These results show that once students have taken the course, their perception about the components that should be present in the teaching of physical education change. In all the items, the average assessment is higher in the post-test than in the pre-test. The greatest increase in the means of the post-test in relation to the pre-test is present in the following items: “It favors the development of decision-making skills”, “it represents a challenge, understood as something to overcome within learners’ possibilities” and “it is relevant learning in cognitive terms”.

In general terms, the results of the pre-test are confirmed by the analysis of qualitative information requested from the students. In some narratives, the playful nature of physical education is contrasted with that of other subjects, highlighting its contribution to the “disconnection” from the usual school routine. Furthermore, students also emphasize the opportunity that this subject provided for socializing with classmates, especially during cooperative games.

“I also liked the atmosphere in the classroom, much more relaxed than in other subjects, where we could socialize with all classmates and get to know each other better”(S25).

“A different class, transcending the limits of the classroom and its classic rules, conducted standing, in motion, dynamically (…) with the playful touch they almost always had”(S38).

“The best memories of physical education are the moments and anecdotes I shared with my classmates; it was the time to disconnect from other subjects”(S39).

3.3. Contributions of “Didactics of Physical Education” to Teaching Professional Competencies

Once the course was completed, the surveyed students also assessed the degree to which they had worked on the different key competences established in the course syllabus, included in the Resolution of 19 February 2015, of the University of Santiago de Compostela, which contains the curriculum for the degree in primary education teaching [57].

The average scores obtained show that in general terms, students consider that the course contributed to the development of all the competences described (Table 3). The highest average score was for “favoring the acquisition of habits and skills for autonomous and cooperative learning among students” (4.63), followed by “helping to reflect on classroom practices in order to innovate and improve teaching work” (4.56). Then, they also highlighted the value of the subject for “acquiring teaching–learning procedures” (4.53), “stimulating and valuing effort, perseverance and personal discipline in students” (4.53) and “improving coexistence both inside and outside the classroom paying attention to the peaceful resolution of conflicts” (4.46). On the other hand, the competence with the lowest average rating is that of “facilitating the interrelation of disciplines between the different curricular areas of primary education” (3.97).

Table 3.

Extent to which students consider that the subject contributes to the development of following competences.

These assessments regarding the competencies addressed in the subject and their training as teachers are related to the results obtained from the narratives provided by the participants. Indeed, many of the positive aspects highlighted in these narratives about the teaching role correspond to the competencies that they have also rated more positively through the questionnaire.

“… thanks also to the teacher we had because we learned new things and had fun playing”(S5).

“The innovations by the teachers, taking advantage of seasons like autumn to do what we called ‘The chestnut games’”(S6).

“In primary school (…) the teacher tried to make us learn by playing with everyone”(S15).

“… we had an excellent teacher with whom we played a lot of games…”(S23).

“The best experiences in PE that I remember are related to the teacher we had in the third cycle of Primary school. His concern for us to learn and have a good time in class was evident”(S31).

On the other hand, other participants also include the teaching role in some of their worst memories, mainly linked to the aforementioned aspects: resistance tests, not considering the different characteristics of students, etc.

“… we had a teacher who conducted classes in the traditional method, focusing on high-demand exercises, and if you didn’t reach the expected level, it influenced our grade negatively”(S27).

“… my worst memories in physical education are related to the teacher who taught the subject in the second cycle”(S31).

“My worst memories are with a teacher who barely got involved in teaching practice…”(S40).

Some students clarify that, in many cases, this more traditional methodology did not consider the diversity of students, leading to feelings of helplessness and discomfort in front of the rest of the group.

“The endurance tests, speed, strength, etc. Since we were only valued based on the results, we achieved without taking into account our effort and abilities”(S7).

“When some teachers made us do some exams as an exam in front of the whole class, without practicing much beforehand, as if everyone should know how to do them. And until you did something, you were there in front of everyone”(S9).

Therefore, the didactic approach of the subject, its methodological strategies, and the way of addressing student diversity have been revealed in our study as essential elements in satisfaction with the subject during primary education and the shaping of good and bad memories. For this reason, the training they receive and the competencies that shape the curriculum become particularly relevant.

4. Discussion

The primary aim of this study is to investigate the beliefs and prior conceptions held by prospective teachers upon entering initial teacher training. To achieve this, we examine their recollections as students in schools and assess the extent to which students’ perceptions regarding the objectives and components of physical education shift after completing the course titled “Didactics of Physical Education” within the primary education degree program. For this endeavour, we will juxtapose students’ initial assessment of physical education, shaped by their personal experiences (pre-test), their subsequent assessment upon finishing the course (post-test), and their narrative recollections and memories of childhood.

Regarding students’ pre-existing beliefs and concepts about physical education, our findings align with observations made by other scholars concerning the significance attributed by prospective teachers to competitiveness [22], as well as the correlation identified between competitive sports and their attitudes toward physical education in schools. Indeed, these findings resonate with the societal perception of the subject, which is particularly evident in questionnaire items related to effort and competitiveness [27]. Furthermore, the connection drawn between competitiveness and traditional pedagogies in the instruction of physical education is noteworthy, albeit not analyzed in our study.

In recent academic years, we conducted an experiment on the subject of physical education in the primary education degree program with the aim of highlighting the students’ experiences and memories throughout their school trajectory [58]. The majority of students expressed satisfaction with the subject both in primary and secondary education, with a slightly lower satisfaction in the latter. They associate positive memories with the subject to relationships with classmates and the classroom atmosphere. They particularly emphasize the playful and socializing nature of physical education as a means for building knowledge, collaboration, and enjoyment with classmates, especially in primary education. This characteristic is reinforced by the unique nature of physical education in the school context, deviating from classroom routines and teaching practices, and creating a context of disconnection that promotes contact and increased personal interaction.

The teacher’s role, especially their commitment to the subject and concern for students, and the classroom atmosphere, have a greater influence than the specific content of the subject. These observations generally align with findings from previous studies [58,59].

Despite this predominant positive view, the analysis of students’ discourse regarding their autobiographical experience has revealed some negative experiences and memories. These negative aspects are identified with the content related to physical performance, relationships with the evaluation of individuals and their performance, and the lack of attention to the diversity of students. Excessive emphasis on competitiveness is also highlighted. These negative opinions toward physical education are especially directed at the secondary education stage. Similar results have been demonstrated in other studies [60,61] concerning fears in physical education and how they condition the subject’s assessment.

It is also worth highlighting the coincidence with other studies [24] on the importance given to values, and the fact that the results of our sample show outstanding scores in items such as participation, fun, socializing, learning, and playing, which increase after taking the course.

In relation to the assessment that students’ give to basic competences addressed in the course, those related to the contents of the subject itself, its teaching–learning procedures, and innovative practices are particularly noteworthy. These coincide with what has been pointed out by other studies [14] on the importance of knowledge of the contents of physical education, active participation in its activities, and the need to put the contents of the subject into practice.

On the other hand, those competences linked to concepts of educational inclusion (values, diversity, gender, conflict resolution, equity, citizenship…), although maintaining high scores, are situated below other individualistic values which are closer to the tradition of effort inherent to physical education, mostly linked to perseverance and discipline. Likewise, it can also be noted that the lowest score is given to the interrelation of physical education with other subjects. From our perception, we could explain this based on the traditional ways of understanding physical education, which is taught in schools by “specialists”, in differentiated places and environments (the playground, gymnasium…), and with its content (related to the body and movement) being very different from the rest of the school subjects. This leads to an excessive fragmentation of teaching tasks in schools with a lack of knowledge of the educational intentions of physical education and a reductionism to aspects associated with sports and healthy habits [25].

Unless the prior beliefs and concepts that pre-service teachers bring with them are critically examined, students will tend to repeat them and perpetuate these models, especially those that generate deep emotions that were experienced first-hand or in close environments [62]. With our work, we have tried, as far as possible, to understand the beliefs that our students have about physical education in school, the characteristics and purposes they attribute to it, and the competences that are developed through the Didactics of Physical Education course, contrasting the results when the course begins, and once it has been completed. Cautiously, we can say that the passage through the course increases the educational appreciation and beliefs towards physical education of the future teachers. As Wrench and Garrett [6] remind us, the process of becoming a teacher and the construction of teacher identity is interwoven with beliefs, experiences, and learning, which need to be accommodated and negotiated over the course of professional life.

5. Conclusions

The impact of the role played by the teacher in the learning process of students is undeniable. In the construction of this teaching role, some of the factors to be considered are prior experience and beliefs. The results obtained in this study evidence that the time spent in the “Didactics of Physical Education” course changes the perception that learners have towards deeply rooted beliefs and previous concepts in their way of conceiving the course. After taking the course (post-test), learners attribute more innovative and positive concepts to physical education, such as learning, socialization, participation, or fun.

With the necessary precautions, we can affirm that participation in this research has provided us with evidence of the reflective component of this approach by the students. Challenging and confronting pre-service teachers’ beliefs about education within educator preparation programs constitute a significant contribution to the field. The use of a concurrent mixed-methods study for studying the beliefs and perceptions of future teachers adds a new and distinctive dimension as the literature has rarely captured these perspectives. Both approaches complement and expand our vision of what physical education pedagogy is and means for future teachers.

Analyzing students’ discourse about their memories and experiences provides a framework for understanding various subject contents in physical education didactics, especially the most common pedagogical models and how they influence and shape teaching practices in the classroom. Helping future teachers understand these models, the reasons supporting them, and the practices they promote contributes to a deeper understanding of the educational value of physical education in primary education. It also aids them in making curriculum decisions when formulating their pedagogical approaches in lesson plans for the subject and its implications for other subjects in primary education, ultimately contributing to the construction of their teaching identity.

Moreover, it is worth highlighting the significance and value of this approach to the subject within the broader context of the degree program. We believe that this perspective is relevant for future primary education teachers since it critically situates personal experiences within the context of the Physical Education Didactics course and the general primary education degree—without a specific mention of physical education. For most students, this subject is considered residual, and they do not intend to delve into it since they will not be teaching it in their usual professional roles. Beyond any potential vocation towards teaching physical education, we find it important for their formation as future primary education teachers to familiarize themselves with different models and trends guiding physical education in schools. This knowledge can serve them in critically analyzing elements of the curriculum and teaching practices, fostering reflective teachers who make intelligent decisions in contexts of increasing uncertainty and complexity.

This research shows the need for a new approach to the meaning of physical education in the primary school curriculum to break with a restrictive epistemological and methodological tradition, strongly linked to a competitive practice of sport which is very present in society in general. Physical education at school should be oriented towards the knowledge of one’s own body, the search for the integral wellbeing of the person, and a healthy life [63,64]. New scientific findings provide a considerable amount of information that needs to be transmitted to future physical education professionals [65]. The PE class must be enriched by new curricular approaches [66] that guide new methodological proposals based on experiencing and experimenting with the body [67] (knowing and analyzing the different dimensions of the body, identifying its characteristics, and recognizing the functional diversity of bodies as a collective enrichment); acquiring healthy habits for the care of the body (sports practice, nutrition, postures); learning about the relationship between the body and mind as well as the relationship between sport and lifestyle and the impact of sport on skills such as attention, concentration, social engagement, and its influence on the nervous system; discovering the pleasure of engaging in sport to feel good and as a tool to improve resilience, self-estimation, and learning to enjoy the rewards of effort and self-improvement; and experiencing sport as a space for socialization and the acquisition of skills in a cooperative environment.

To complement the work carried out in the Physical Education Didactics course, it is advisable that throughout their university education, students can learn about experiences developed in schools that include new curricular and methodological approaches. In this sense, the practicum periods that our students carry out in schools during their degree studies can be very useful for them to experience the possibilities of new perspectives for teaching physical education. At the same time, the students will also be able to perceive the demands of a part of society that understands that the area of physical education should play an important role in the integral development of people; hence, there is a need to deepen the students’ understanding of the importance of physical education in primary school.

It should also be noted that the study has certain limitations, like the non-random selection of participants and the fact that it is based exclusively on the perception of the subjects involved. These limitations and the type of study do not allow us to generalize the results; although it does reaffirm the need to continue reflecting on how these beliefs and prior experiences influence the initial training of future physical education teachers. In this sense, we believe it is necessary to continue to study in depth how these beliefs may be conditioned by what students consider good teaching and good references in the subject of physical education. Likewise, we consider that these first results should be complemented with other studies, for instance in different stages of initial training (after school placement) or in different periods of the professional development of teachers, thus continuing the research conducted by previous studies [44].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.E.-N. and B.G.-A.; Methodology, B.G.-A. and S.L.-M.; Formal analysis, R.E.-N. and B.G.-A.; Investigation, R.E.-N., B.G.-A. and M.M.C.-R.; Writing—original draft, R.E.-N. and B.G.-A.; Writing—review & editing, R.E.-N., B.G.-A., S.L.-M. and M.M.C.-R.; Supervision, R.E.-N., B.G.-A., S.L.-M. and M.M.C.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethic Committee Name: Comité de Bioética da Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. Approval Date: 7/December/2023. Approval Code: USC 75/2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Loughran, J.J.; Hamilton, M.L.; LaBoskey, V.K.; Russell, T.L. (Eds.) International Handbook of Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, S.; Aburto, R.; Poblete, F.; Aguayo, O. The school as a space to become a teacher: Experiencies of Physical Education teachers in training. Retos 2022, 43, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthagen, F.A.J.; Nuijten, E.E. Core reflection: Nurturing the human potential in students and teachers. In International Handbook of Holistic Education; Miller, J.P., Nigh, K., Binder, M.J., Novak, B., Crowell, S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2022; pp. 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Twomey-Fosnot, C.; Stewart-Perry, R. Constructivism: A Psychological Theory of Learning. In Constructivism: Theory, Perspectives, and Practice, 2nd ed.; Twomey Fosnot, C., Ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lortie, D.C. Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Wrench, A.; Garrett, R. Identity work: Stories told in learning to teach physical education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2012, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, R.; Aloisi, C.; Higgins, S.; Elliot Major, L. What Makes Great Teaching? Review of the Underpinning Research; Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring, Durham University: Durham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, V. The role of attitudes and beliefs in learning to teach. In Handbook of Research on Teacher Education, 2nd ed.; Sikula, J., Buttery, T., Guyton, E., Eds.; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 102–119. [Google Scholar]

- Feiman-Nemser, S. From preparation to practice: Designing a continuum to strengthen and sustain teaching. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2001, 103, 1013–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnon, S.; Reichel, N. Who is the ideal teacher? Am I? Similarity and difference in perception of students of education regarding the qualities of a good teacher and of their own qualities as teachers. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2007, 13, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.K.; Delli, L.A.M.; Edwards, M.N. The good teacher and the good teaching: Comparing beliefs of second grade students, preservice teachers, and inservice teachers. J. Exp. Educ. 2004, 72, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harford, J.; Gray, P. Emerging from somewhere: Students teachers, professional identity and the future of teacher education research. In Overcoming Fragmentation in Teacher Education Policy and Practice; Hudson, B., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Capel, S.; Hayes, S.; Katene, W.; Velija, P. The interaction of factors which influence secondary student physical education teachers’ knowledge and development as teachers. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2011, 17, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chróinín, D.N.; O’Sullivan, M. Elementary Classroom Teachers’ Beliefs Across Time: Learning to Teach Physical Education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2016, 35, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Zwiep, S. Elementary teachers’ understanding of students’ science misconceptions: Implications for practice and teacher education. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2008, 19, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambouri, M. Investigating early years teachers’ understanding and response to children’s preconceptions. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2016, 24, 907–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J.A.; Lederman, N.G. Science teachers’ diagnosis and understanding of students’ preconceptions. Sci. Educ. 2003, 87, 849–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerum, Ø.; Bartholomew, J.; McKay, H.; Resaland, G.K.; Tjomsland, H.E.; Anderssen, S.A.; Leirhaug, P.E.; Moe, V.F. Active Smarter Teachers: Primary School Teachers’ Perceptions and Maintenance of a School-Based Physical Activity Intervention. Transl. J. ACSM 2019, 4, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österling, L.; Christiansen, I. Whom do they become? A systematic review of research on the impact of practicum on student teachers’ affect, beliefs, and identities. Int. Electron. J. Math. Educ. 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grub, A.S.; Biermann, A.; Brünken, R. Process-based measurement of professional vision of (prospective) teachers in the field of classroom management. A systematic review. J. Educ. Res. Online 2020, 12, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matanin, M.; Collier, C. Longitudinal Analysis of Preservice Teachers’ Beliefs about Teaching Physical Education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2003, 22, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.; O’Donovan, T.M. Pre-service physical education teachers’ beliefs about competition in physical education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2013, 18, 767–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, S.; De la Vega, R.; Martínez-Almira, M.M. Primary and Secundary School Physical Education Teacher’s Beliefs. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Física Deport. 2015; 15, 506–526. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Sánchez, M.; Romero Sánchez, E.; Izquierdo Rus, T. Creencias del profesorado de Educación Física en Educación Primaria sobre la educación en valores. Educ. Siglo XXI Rev. Fac. Educ. 2019, 37, 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Calvo, G.; Gerdin, G.; Philpot, R.; Hortigüela-Alcalá, D. Wanting to become PE teachers in Spain: Connections between previous experiences and particular beliefs about school Physical Education and the development of professional teacher identities. Sport Educ. Soc. 2021, 26, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre Medina, M.J.; Pérez García, M.P.; Blanco Encomienda, F.J. Análisis de las creencias que sobre la enseñanza práctica poseen los futuros maestros especialistas en Educación Primaria y en Educación Física. Un estudio comparado. Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2009, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera García, E.; Trigueros Cervantes, C.; Doña, A.M. The Big Bang Theory o las reflexiones finales que inician el cambio. Revisando las creencias de los docentes para construir una didáctica para la Educación Física Escolar (The Big Bang Theory or the final reflections that trigger change. Reviewing teacher. Retos 2020, 37, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Álvarez, J.L.; Velázquez-Buendía, R.; Martínez, M.E.; Díaz del Cueto, M. Creencias y perspectivas docentes sobre objetivos curriculares y factores determinantes de actividad física. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Física Deport. 2010, 10, 336–355. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, M.C.; Gómez-Alonso, M.T.; Pérez-Pueyo, Á.; Gutiérrez-García, C. Errores en la intervención didáctica de profesores de Educación Física en formación: Perspectiva de sus compañeros en sesiones simuladas. Retos. Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deport. Recreación 2016, 29, 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, A. Carter Review of Initial Teacher Training (ITT); DfE: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Clandinin, D.J.; Connelly, M. Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, A.; Fletcher, T.; Schaefer, L.; Gleddie, D. Conducting Practitioner Research in Physical Education and Youth Sport; Reflecting on Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Armour, K. The way to a teacher’s heart: Narrative research in physical education. In Handbook of Physical Education; Kirk, D., MacDonald, D., O’Sullivan, M., Eds.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 467–485. [Google Scholar]

- Devís, J. La investigación narrativa en la educación física y el deporte. Movimento 2017, 23, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, F.; Garrett, R. Narrative inquiry and research on physical activity, sportand health: Exploring current tensions. Sport Educ. Soc. 2016, 21, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clandinin, D.J.; Connelly, F.M. Storying and restorying ourselves: Narrative and reflection. In The Reflective Spin: Case Studies of Teachers in Higher Education Transforming Action; Chen, A.Y., Van Maanen, J., Eds.; World Scientific: Singapore, 1999; pp. 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Goodson, I.F. Hacia un desarrollo de las historias personales y profesionales de los docentes. Rev. Mex. De Investig. Educ. 2003, 8, 733–758. [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar, A. Las historias de vida del profesorado. Rev. Mex. De Investig. Educ. 2014, 19, 711–734. [Google Scholar]

- Elías, M. La construcción de identidad profesional en los estudiantes del profesorado de Educación Primaria. Profesorado. Rev. de Currículum y Form. de Profr. 2016, 20, 335–365. [Google Scholar]

- González-Calvo, G.; Arias-Carballal, M.A. Teacher´s personal-emotional identity and its reflection upon the development of his professional identity. Qual. Rep. 2017, 22, 1693–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortigüela, D.; Hernando, A. “Dedícate a otra cosa”: Estudio autobiográfico del desarrollo profesional de un docente universitario de Educación Física. Qual. Res. Educ. 2017, 6, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu, S.M.B.; Nóbrega-Therrien, S.M.; Silva, S.P. Experiência com narrativas autobiográficas na (auto)formação para a pesquisa de licenciandos em educação física. Rev. Educ. Formaçao 2017, 2, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Bryant, C.P.; O’Sullivan, M.; Raudensky, J. Socialization of Prospective Physical Education Teachers: The Story of New Blood. Sport Educ. Soc. 2000, 5, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eirín-Nemiña, R. Reconstruyendo la materia de Didáctica de la Educación Física desde la perspectiva autobiográfica del alumnado (Reconstructing the subject of Didactics of Physical Education from students’ autobiographical perspective). Retos 2020, 37, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, P. Metodología de la Investigación, 6th ed.; McGrawHill Education: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Mendoza, C. Metodología de la Investigación. Las Rutas Cuantitativa, Cualitativa y Mixta; Mc Graw Hill Education: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Johnson, R.B.; Collins, K.M. Call for mixed analysis: A philosophical framework for combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. Int. J. Mult. Res. Approaches 2009, 3, 114–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. Mapping the Field of Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2009, 3, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Torrado, M. Estudios tipo encuesta. In Metodología de la Investigación Educativa; Coord, R.B., Ed.; La Muralla: Madrid, Spain, 2004; pp. 130–147. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J.H.; Schumacher, S. Investigación Educativa, 5th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, F.J.; Cosenza, C. Writing Effective Questions. In International Handbook of Survey Methodology; Leeuw, E.D., Hox, J.J., Dillman, D.A., Eds.; Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 136–160. [Google Scholar]

- Sabariego, M.; Massot, I.; Dorio, I. Métodos de investigación cualitativa. In Metodología de la Investigación Educativa; Bisquerra, R., Ed.; La Muralla: Madrid, Spain, 2016; pp. 285–320. [Google Scholar]

- Jorrín, I.M.; Fontana, M.; Rubia, B. Investigar en Educación; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia, M.P. Nonprobability sampling. In Encyplopedia of Survey Research Methods; Lavrakas, P.J., Ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2008; pp. 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- University of Santiago de Compostela. Resolución del 19 de febrero de 2015, de la Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, por la que se publica el plan de estudios de Graduado en Maestro de Educación Primaria. Boletín Of. Del Estado 2015, 70, 25316–25320. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2015-3086 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Moreno, J.A.; Hellín, M.G. El interés del alumnado de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria hacia la Educación Física. Rev. Electrónica De Investig. Educ. 2007, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Peris, A.; Lizandra, J. Cambios en la representación social de la educación física en la formación inicial del profesorado. Retos. Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deport. Recreación 2018, 34, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina Soria, M.; Pascual Arias, C.; López Pastor, V.M. El uso de sistemas de evaluación formativa y compartida en las aulas de educación física en Educación Primaria. Educ. Física Deport. 2020, 39, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monforte, J.; Pérez-Samaniego, V. O medo em Educaçao Física: Uma história reconhecível. Movimento. Rev. Educ. Física UFRGS 2017, 23, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, J.E.; Quinn, F.; Miller, J.A. Teacher Biography: SOLO Analysis of Preservice Teachers’ Reflections of their Experiences in Physical Education. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 45, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcante de Sousa, N.; Calcante Targino, F.R.; Rocha Braz Benjamim, E.M. O naturismo: Diálogos sobre corpo, natureza e cultura. Lect. Educ. Física Deport. 2023, 28, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Lozano, S.; González-Palomares, A. ODS 5. Igualdad de género y Educación Física: Propuesta de intervención mediante los deportes alternativos. Retos 2023, 49, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subirats, J. Aprendizaje organizado (AO): De la simplicidad de las tareas de aprendizaje a la complejidad de las tareas competenciales en Educación Física. J. Neuroeduc. 2021, 2, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujica Johnson, F.N. Philosophical analysis of the Physical Education curriculum in Chile. Retos 2022, 44, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oroño Lugano, M.; Azaustre Lorenzo, M.C. Educación, enseñanza, escuela y educación física: Sentidos, relaciones y puntos de encuentros a la luz de la praxis docente. MLS-Educ. Res. 2022, 6, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).