Abstract

This study aimed to understand how different dimensions of online learning engagement were influenced by learners’ self-regulated learning (SRL) and their perceptions of teaching, cognitive, and social presence in the community of inquiry (CoI) framework. A structural equation modelling analysis of survey responses from 154 online Chinese-as-a-foreign-language learners showed that the level of learners’ SRL positively influenced their perceptions of teaching, cognitive, and social presence and consistently directly impacted all dimensions of students’ learning engagement. Regarding the different dimensions of engagement, learner’ perceived CoI had different mediating effects. Affective engagement was influenced by learners’ perceptions of cognitive and social presence, while social engagement was influenced by learners’ perceptions of social presence. Cognitive and behavioural engagements were influenced by learners’ perceptions of teaching presence. The results highlight the importance of SRL in the CoI framework for enhancing learning engagement, suggesting integrating SRL training into instructional design in the online learning environment. In addition, the effects of various dimensions of the CoI framework on learning engagement inform pedagogical implications to enhance online learning engagement, such as building an online learning community to strengthen affective and social engagement while strengthening teaching presence to improve cognitive and behavioural engagement.

1. Introduction

The number of overseas Chinese as a Foreign Language (CFL) learners has increased greatly in recent years. According to the latest report published by the Ministry of Education, more than 25 million people were learning Chinese outside China [1]. In the meantime, the number of online CFL learners has been growing. Taking the Chinese Plus platform developed by the Center for Language Education and Cooperation [2] in China as an example, 16,000 online courses have been offered, benefiting seven million Chinese learners in 201 countries and regions around the world [3]. Although online education provides learners with access to diverse learning opportunities, transcends geographical boundaries, and caters to a wide range of educational needs, learners’ online learning experiences and engagement have become issues that might hinder the quality of online learning [4]. Learning engagement refers to the effort learners make to understand and master knowledge and skills while participating in learning activities [5]. Studies have shown that learning engagement can enhance learners’ online learning completion rates and improve learning effectiveness; thus, it is an important indicator for evaluating the quality of online education [6]. Research has demonstrated that self-regulated learning (SRL), characterized by a learner’s ability to set goals, monitor progress, and adapt strategies, can foster online learning engagement [7]. The community of inquiry (CoI) framework emphasizes social, cognitive, and teaching presence and promotes learner engagement in online educational contexts [8]. Both concepts have been studied extensively in various online learning environments with promising results. However, CFL online learning introduces unique challenges.

Online Chinese language learners often represent a mosaic of cultural backgrounds with diverse prior experiences and language proficiency [9]. Their motivations, expectations, and cultural dispositions can significantly impact their self-regulated learning behaviours and responses to the CoI framework. Therefore, it is essential to investigate whether the effects of self-regulated learning and the CoI framework on online learning engagement are consistent when applied to this intricate cultural landscape.

This study addresses a critical gap in the existing literature and offers valuable insights into the complex interplay of self-regulated learning, the CoI framework, and online learning engagement within the multifaceted cultural landscape of CFL learning.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Learning Engagement

This study defines learning engagement as a multifaceted construct encompassing the cognitive, affective, behavioural, and social dimensions of learner participation [10,11]. Cognitive engagement refers to the performance of learners’ cognitive activities in the learning process [12]; behavioural engagement refers to the actual behaviour of learners in the learning process, such as participating in discussions [13]. Affective engagement includes the learners’ emotional feelings during the learning process, such as anticipation and enjoyment [14]. Social engagement refers to the learners’ affiliation in discourse and sense of belonging [15]. The absence of engagement (as exemplified by lacklustre participation), reduced motivation, and limited interaction pose a significant threat to the success and quality of online language education [16]. Learners who fail to effectively engage in the online environment may struggle to develop the language proficiency, cultural competence, and sense of belonging crucial for their success as language learners [11,17].

Previous studies have investigated online language learners’ engagement in a variety of contexts and the influencing factors [18,19,20]. For instance, Luan and colleagues (2023) investigated the learning engagement of online English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Conducting a five-point Likert questionnaire among 615 university students in China, the participants showed a medium level of learning engagement in cognitive (3.87/5), behavioural (3.69/5), affective (3.61/5), and social dimensions (3.57/5), ranging from 3.57 to 3.87. This study further found that teacher and peer support positively enhanced students’ online learning engagement, which is of great significance in an online context where learners might feel disconnected [18]. In addition, studies have revealed contextual and individual factors that may influence learning engagement, such as teacher–student relationships, task design, and interests [21,22,23].

Among the serious contextual and individual factors that affect online learning engagement, CoI and SRL have received significant research interest [24,25,26]. However, the impact of learners’ perceived CoI and SRL levels on CFL learners’ engagement has received less attention. To fill this research gap, this study recruited CFL learners to explore the relationships among CoI, SRL, and online language learning engagement.

2.2. Community of Inquiry

The concept of CoI is rooted in social constructivism, which aims to create deep and meaningful learning experiences through social presence, cognitive engagement, and teaching [27]. Since being proposed by Garrison et al. in the late ’90s, CoI has become one of the most widely used theoretical frameworks in online learning research [8].

The framework comprises three essential components: cognitive, teaching, and social presence. Cognitive presence is the degree to which learners actively engage in reflective thinking and meaningful discussions within a critical community of inquiry, resulting in the construction of knowledge and understanding [8]. Teaching presence involves the design and organization of instruction, which depends significantly on the instructor’s ability to guide and support learners in their learning process [8]. Social presence refers to a sense of belonging and connectedness among learners within a virtual community [28], including the feeling, perception, and reaction of being connected to others through online communication [29]. Studies suggest social presence is critical to enhancing the effectiveness of online learning [30].

Studies have found that learners’ sense of CoI significantly improved their online learning engagement. For example, teaching presence promotes meaningful interactions and fosters critical thinking. Effective teaching presence has been found to positively influence students’ perceptions of the quality of their learning environment and their ability to construct knowledge [31]. Li and colleagues (2021) investigated online learning engagement among Chinese secondary school students and teachers during the pandemic and found teaching presence to be an important factor in enhancing online learning engagement [25]. Cognitive and social presence were also believed to be associated with deep learning and engagement. Akyol and Garrison (2011) identified that learners’ perceived cognitive presence significantly correlated with learning and learning satisfaction [32]. Researchers have also found a significant impact of social presence on online learning engagement [33,34]. Yen and colleagues (2022) further found that social presence was a key predictor of social interaction and connectivity in the online learning community. Learners with higher social presence are more likely to take on significant roles such as “influencer, liaison, transmitter, social strategist, and prestigious figure of a community of learners” [31] (p. 27).

Although learners’ sense of CoI was found to have a significant and positive impact on learning engagement in the online learning context [31,32,33,34], few studies examined its influence on CFL learners’ online learning engagement. Considering learning engagement as a multifaceted construct encompassing the cognitive, affective, behavioural, and social dimensions of learner participation, this study aims to understand the impacts of learners’ perceived CoI on the different dimensions of online learning engagement.

2.3. Self-Regulated Learning

Self-regulated learning (SRL) refers to the process by which individuals actively control and manage their actions, thoughts, and emotions to achieve their learning goals. It involves goal setting, planning, self-monitoring, self-regulation strategies, and self-evaluation [33,35]. It empowers learners to take ownership of their learning and adapt to different learning environments and is, therefore, critical for online learning engagement [26,34,35,36,37]. By contrast, learners who lack self-regulation skills may struggle to remain engaged and motivated in online learning. They may procrastinate, struggle with time management, and have difficulty organizing their learning activities. This can lead to lower engagement, completion rates, and higher dropout rates [35,36,37,38,39].

Studies have found that SRL positively enhances learning engagement [26,34,36,37,38,39]. For example, Wei and colleagues (2023) found that SRL strategies significantly impacted learning engagement [26]. Their study demonstrated that learners who employed SRL strategies such as goal setting, help-seeking, and time management significantly enhanced their engagement in learning activities. By actively regulating their learning processes, these students took control, monitored their progress, and adjusted strategies as needed, which effectively boosted their overall engagement and participation in educational tasks. Consistent findings were reported by Azhari et al. (2023), in which SRL significantly and directly impacted learning engagement through structural equation modelling partial least square (SEM-PLS) analysis [40]. Zhao and Cao (2023) conducted a detailed examination of learning engagement, focusing specifically on affective and behavioural engagement. Their study identified SRL as a significant predictor of both affective and behavioural engagement, highlighting the critical role SRL plays in enhancing students’ emotional and participatory aspects of learning [41]. In another study conducted among 4503 learners from 17 Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), SRL was also found to be a significant predictor of affective dimensions in online learning [42]. However, the impacts of SRL on social engagement in online language education are less examined.

Moreover, research has found that learners’ SRL levels influence their perceived CoI [43,44]. For example, Cho and colleagues (2017) examined the effects of self-regulated learning levels on college students’ perceptions of CoI and their affective outcomes. This study involved 180 undergraduate students enrolled in an online course and surveyed their self-regulated learning levels and their perceptions of CoI for online learning. Cluster analysis was conducted to determine the clusters of online students based on their self-regulated learning levels. One-way ANOVA tests were conducted, and it was found that highly self-regulated students demonstrated a stronger sense of CoI than low self-regulated students [43]. Their study provided some preliminary evidence that learners’ sense of CoI may play a mediating role when examining the impacts of SRL on learners’ affective learning engagement. Doo and Bonk (2020) [33] investigated the mediating role of social presence between SRL and engagement, identifying SRL as directly and indirectly influenced learning engagement, with social presence as a mediator. Meanwhile, social presence was also found to have a direct and positive impact on learning engagement. In a more recent study conducted by Doo and colleagues (2023), cognitive presence was found to play a mediating role when examining SRL and learning engagement [24], suggesting that SRL positively and directly affected learning engagement; SRL indirectly affected learning engagement through cognitive presence; and cognitive presence directly affected learning engagement.

Previous studies provided some insights into the interaction between SRL, CoI, and online learning engagement. The current study regards online language learning engagement as a multifaceted construct and aims to examine the mediating role of learners’ perceived CoI between SRL and different dimensions of learning engagement.

3. Methods

3.1. Hypotheses

Existing literature has found that SRL positively enhances learning engagement [40,41,42], as well as learners’ perceived CoI [24,26,43,44]. Moreover, learners’ sense of CoI has been found to have a direct and positive impact on their online learning engagement [24,30,31,32,33,34]. Therefore, the current study hypothesized the following:

H1:

Learners’ SRL positively and directly influences all the dimensions of online learning engagement.

H2:

The level of learners’ SRL indirectly influences all dimensions of online learning engagement through perceived CoI.

H3:

Learners’ perceived CoI positively and directly influences all dimensions of online learning engagement.

3.2. Participants

CFL learners attending synchronous online Chinese lectures during the data collection period (April–December 2022) were recruited. A total of 154 CFL learners from 40 countries participated, including Indonesia (n = 37), Pakistan (n = 16), Thailand (n = 13), Vietnam (n = 11), Malaysia (n = 10), Russia (n = 9), India (n = 9), South Korea (n = 5), Laos (n = 4), Japan (n = 3), Morocco (n = 3), Uganda (n = 3), Poland (n = 2), Cambodia (n = 2), Brazil (n = 2), Bangladesh (n = 2), Tajikistan (n = 2), Kazakhstan (n = 2), Mongolia (n = 1), Philippines (n = 1), United States (n = 1), Comoros (n = 1), Belarus (n = 1), Bolivia (n = 1), Ireland (n = 1), Australia (n = 1), France (n = 1), Fiji (n = 1), Mexico (n = 1), Cyprus (n = 1), Egypt (n = 1), Guatemala (n = 1), Turkey (n = 1), Cameroon (n = 1), Costa Rica (n = 1), Syria (n = 1), Hungary (n = 1), Ghana (n = 1), and Bulgaria (n = 1). All participants were above 18 years of age, and the distribution of grades ranged from the first year of university to the second year of postgraduate education. The language proficiency of the participants was surveyed based on their Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi (HSK) level; HSK Levels 1 to 6 correspond to Levels A1 to C1 of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), respectively [45]. Detailed information on the participants is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ information.

3.3. Instruments

An online language learning engagement scale, community of inquiry survey instrument, and self-regulated learning scale were used to measure learners’ online engagement, perceived CoI, and SRL, respectively (see Appendix A). All statements in the questionnaire used a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). All items were presented in English and Chinese using back-translation strategies. The questionnaire was assigned to 20 learners before the main study to avoid any possible vague languages.

The online language learning engagement scale was mainly adopted by Dixson et al. (2015) [46]. While recent studies highlight the importance of social engagement in second language acquisition, the items to assess learners’ social engagement from Hiver et al. (2024) were also adopted [11]. In total, thirteen items in four dimensions were included to assess learners’ cognitive engagement (e.g., ‘I kept trying my best even when it was hard’), behavioural engagement (e.g., ‘I participated in all learning activities’), affective engagement (e.g., ‘I enjoyed the class’), and social engagement (e.g., ‘If I have problems using online tools, I know I can rely on the other students’).

A community of inquiry survey instrument was adopted by Garrison et al. [8] and referred to Balboni et al. (2018) as it examined the language learning landscape [47]. Twelve items in three dimensions were included to assess learners’ perceived cognitive presence (e.g., ‘Learning activities helped me construct explanations/solutions’), teaching presence (e.g., ‘The instructor provided clear instructions on how to participate in course learning the activities’), and social presence (e.g., ‘My point of views were acknowledged by my classmates’).

A self-regulated learning scale was adopted from Barnard et al. (2009) and included six items that assessed the level of learners’ SRL [48]. According to Zimmerman (1998) [35], SRL involves goal setting, planning, self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and so on. Therefore, sample items included, ‘I set goals to help me manage my study for online courses’ and ‘I summarized my learning in online courses to examine my understanding of what I had learned’. The reliability of each variable is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reliability of variable.

3.4. Data Analysis

Structural equation modelling (SEM), which consists of confirmed factor analysis (CFA) and path analysis, was adopted to test the hypotheses. SPSS 25 was used to conduct descriptive statistical and correlation analysis of the variables. Due to the non-normal distribution of the sample size, which mostly consists of undergraduate students and students with HSK level 4–5, Mplus 1.4 was used to estimate the models using Maximum Likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR), as MLR estimates with standard errors and a chi-square test statistic that is robust to the non-normality of observations [49]. Various model fit indices—absolute goodness-of-fit indices (CMIN/DF ≤ 3), absolute measure of fit indices (SRMR ≤ 0.08), incremental fit indices (CFI ≥ 0.90 and TLI ≥ 0.90), and parsimonious indices (RMSEA ≤ 0.06)—were used to test the model fit [50,51,52].

4. Results

Descriptive statistical analysis, as shown in Table 3, showed that the participants reported strong engagement across the cognitive (M = 4.381, SD = 0.898), affective (M = 4.748, SD = 0.898), behavioural (M = 4.500, SD = 0.858), and social (M = 4.615, SD = 0.896) domains. Furthermore, learners perceived more teaching (M = 4.946, SD = 0.850) and cognitive presence (M = 4.645, SD = 0.845) but less social presence, with the greatest learner variation (M = 4.458, SD = 1.017). Learners also demonstrated positive self-regulated learning strategies (M = 4.416, SD = 0.879). Table 4 presents the results of the correlation analysis among the variables.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistical analysis.

Table 4.

Correlation analysis.

Table 5 presents the model fit indices of the measurement model. Composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were calculated to evaluate construct reliability, indicating satisfactory reliability for all constructs, with values above 0.70 and 0.50, respectively. The model fit indices, including CMIN/DF, SRMR, CFI, and TLI, are satisfactory.

Table 5.

Measurement model fit.

The final model fit indices for path analysis are shown in Table 6. The final model explained 68.3%, 83.3%, 69.8%, and 81.1% of the variation in the learners’ cognitive, affective, behavioural, and social engagement, respectively. The model fit indices were satisfactory.

Table 6.

Final model fit.

As hypothesized, SRL is a significant positive predictor of learners’ perceived CoI and online learning engagement. However, the different CoI components impact the various dimensions of online learning engagement differently.

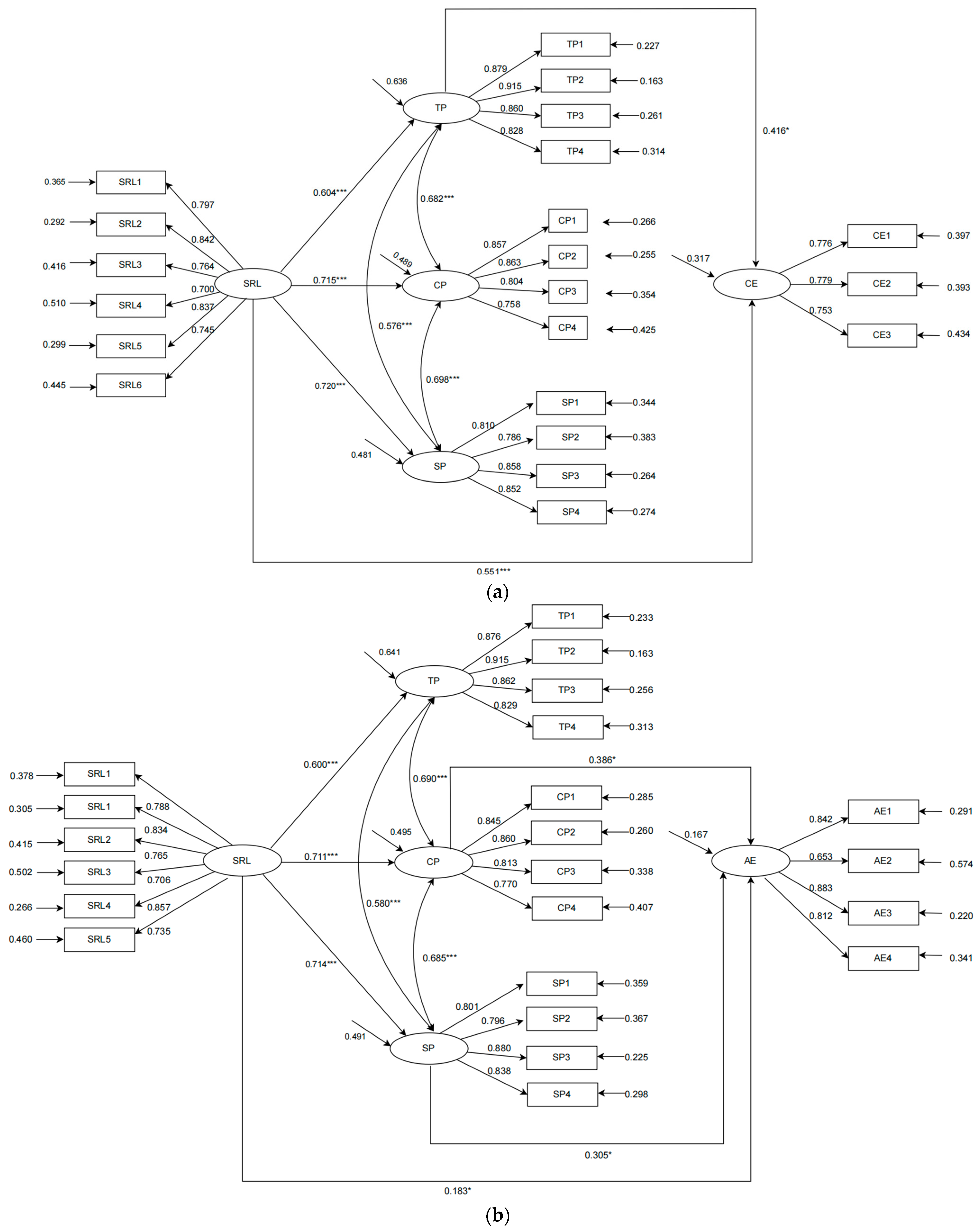

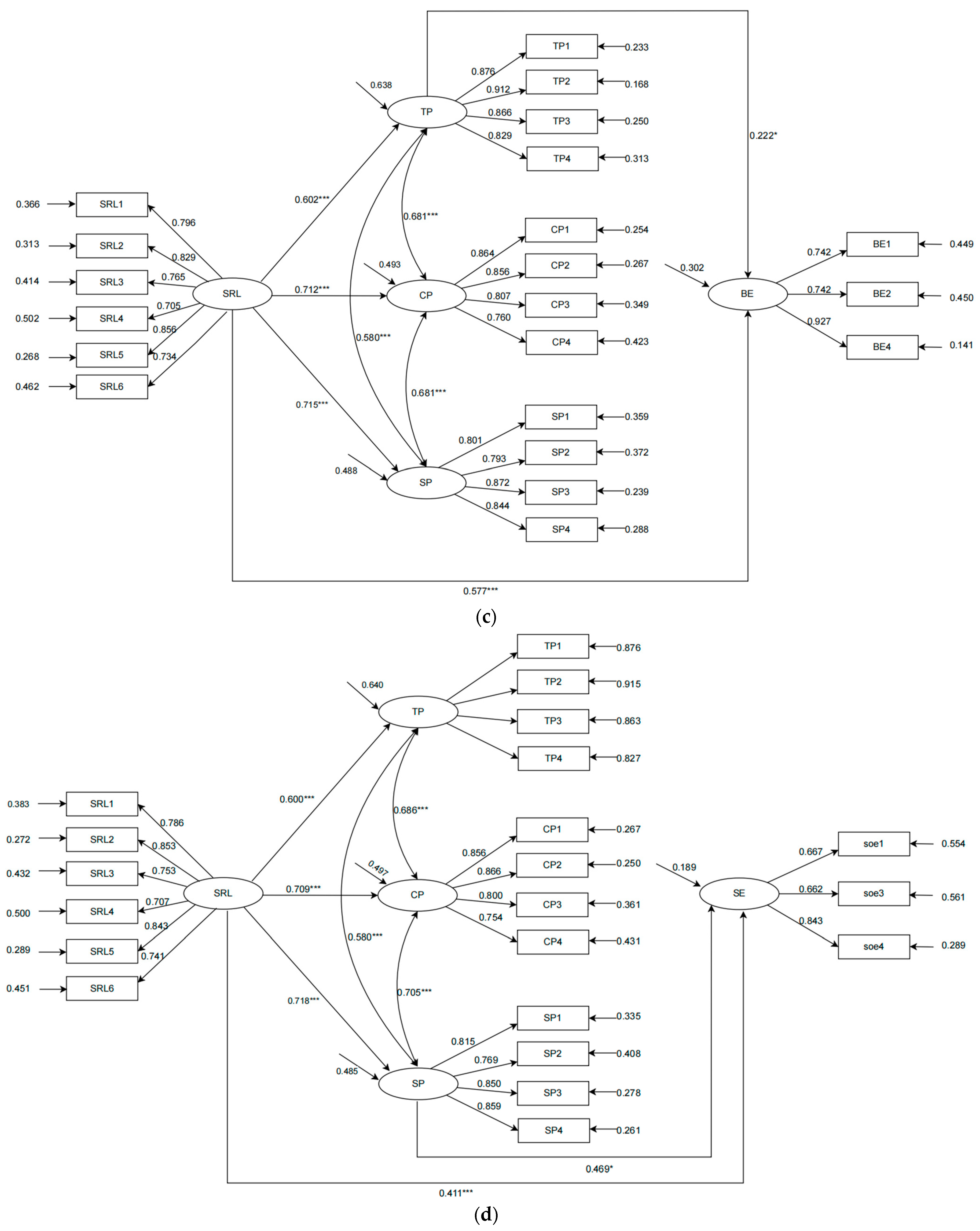

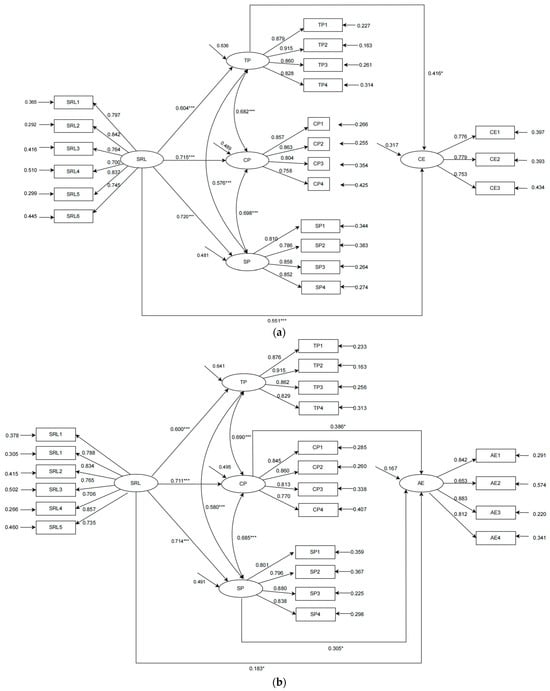

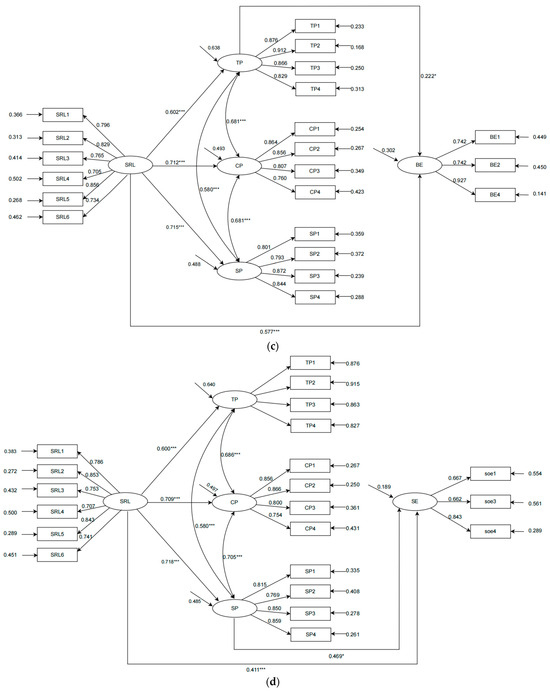

As shown in Figure 1a, SRL had both a significant direct (β = 0.551, p < 0.001) and an indirect effect via teaching presence on cognitive engagement (β = 0.251, p < 0.05). Teaching presence was also found to have a significant positive influence on learners’ cognitive engagement (β = 0.416, p < 0.05). Figure 1b shows the final affective engagement model. SRL had a significant direct (β = 0.183, p < 0.05) and an indirect effect via social (β = 0.217, p < 0.05) and cognitive presence (β = 0.275, p < 0.05) on learners’ affective engagement. Furthermore, learners’ affective engagement was directly and significantly influenced by social (β = 0.305, p < 0.05) and cognitive presence (β = 0.386, p < 0.05) but not significantly by teaching presence (β = 0.125, p > 0.05). Regarding learners’ behavioural engagement, as shown in Figure 1c, SRL (β = 0.577, p < 0.001) and teaching presence (β = 0.222, p < 0.05) were significant positive and direct predictors. SRL also had an indirect effect on learners’ behavioural engagement through teaching presence (β = 0.134, p < 0.05). For learners’ social engagement in Figure 1d, it was found that SRL had both a significant direct effect (β = 0.411, p < 0.001) and an indirect effect through social presence (β = 0.337, p < 0.05). Social presence also directly and significantly influenced learners’ social engagement (β = 0.469, p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Final models of hypotheses: (a) path analysis of cognitive engagement; (b) path analysis of affective engagement; (c) path analysis of behavioural engagement; (d) path analysis of social engagement. *** p < 0.001 and * p < 0.05. CE, cognitive engagement; AE, affective engagement; BE, behavioural engagement; SE, social engagement; SRL, self-regulated learning; SP, social presence; CP, cognitive presence; TP, teaching presence.

Consistent with the hypothesis, SRL significantly influenced learners’ perceived CoI across all four dimensions of online learning engagement. It exhibited a greater influence on social and cognitive presence than on teaching presence across the four dimensions of online learning engagement.

In summary, SRL seemed to play the most critical role in enhancing learners’ online learning engagement, especially cognitive and behavioural engagement. It also enhances learners’ perceived CoI in the online language learning context, which may further influence the different dimensions of online learning engagement. The different CoI components impact the four dimensions of online learning engagement differently. Teaching presence positively and significantly enhances learners’ cognitive and behavioural engagement, social presence positively and significantly enhances learners’ affective and social engagement, and cognitive presence enhances affective engagement positively and significantly.

5. Discussion

Using structural equation modelling analysis, this study explored the roles of SRL, perceived CoI, and learning engagement among 154 online CFL learners. The results validate the initial hypothesis that SRL significantly and positively predicts learners’ perceived CoI and online learning engagement. Notably, SRL plays a dual role, exerting substantial direct and indirect effects through various components of CoI. This underscores the intricate role of SRL in shaping engagement in online learning environments. Cognitive engagement benefited from both the direct and indirect effects of SRL, and teaching presence played a significant role. The affective engagement was directly and indirectly influenced by SRL, social presence, and cognitive presence, whereas teaching presence did not significantly influence it. SRL and teaching presence both had a positive impact on behavioural engagement. In addition, SRL’s impact on behavioural engagement was also mediated by teaching presence. Social engagement, however, experiences a significant direct impact from SRL and indirect influence through social presence, which significantly influences social engagement.

Consistent with previous research results [26,36,40,41,42], SRL positively enhanced learning engagement, emphasizing the crucial role of learners’ self-regulation. Learners who actively engage in learning activities are more likely to employ self-regulated learning strategies to regulate their learning processes [26]. The current study further indicates that SRL significantly enhances online learning engagement across all four domains: cognitive, behavioural, affective, and social engagement. In addition, SRL directly influences and indirectly affects online learning engagement through the three dimensions of learners’ perceived CoI. The overarching influence of SRL on learners’ perceived CoI underscores its pivotal role in enhancing online learning engagement. SRL exerts a more pronounced influence on social and cognitive presence than on teaching presence across the various dimensions of online learning engagement, emphasizing the role of learners’ self-regulation in establishing a sense of community, fostering cognitive exploration, and ultimately promoting engagement within the online learning environment.

Previous studies have identified that perceived CoI impacts online learning engagement [25,31], and this study further found that the three major components of CoI contribute differently to learning engagement.

Firstly, cognitive presence was found to have a significant positive impact on affective engagement, consistent with previous studies [32,53]. Research has found that cognitive presence positively enhances learners’ perceived learning and affective attitudes toward learning activities [24,43]. Lim and Richardson (2021) found that cognitive presence significantly impacted learners’ affective attitudes across all disciplines in their study, and these effects of cognitive presence on affective engagement among CFL online learners echo their findings [53]. Furthermore, social presence enhanced affective engagement, as well as social engagement. Therefore, learners’ perceptions of the online learning community can simultaneously promote their positive affective experiences in the online language classroom and foster affiliation in discourse. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that higher social presence may boost students’ motivation and sense of belonging [33,53]. Online learning is mostly an individual-led autonomous learning context, resulting in a low sense of belonging in online classes [17]. Therefore, this study highlights the importance of learners’ perceived social presence in enhancing their affective and social engagements.

However, learners’ perceived teaching presence was found to have a significant and positive impact on cognitive and behavioural engagement rather than on affective and social engagement. In line with previous studies, perceived teaching presence promoted learners’ cognitive and behavioural engagement [54]. Effective teaching presence positively enhances learners’ knowledge construction. This suggests that teaching presence enhances online learners’ cognitive and metacognitive activities and active participation in the online language classroom [54]. However, teaching presence was not found to enhance learners’ affective engagement in this study, contradicting previous studies [54,55]. These contradictory findings may be attributed to the different course modalities. For instance, Muntaner-Mas and colleagues (2017) identified positive effects of teaching presence on affective engagement in face-to-face classrooms [56]. In another study, Zhang and colleagues (2023) found positive effects of teaching presence on affective engagement among MOOC learners [55]. Although research underscores the importance of teaching presence in enhancing learners’ affective engagement in videocentric asynchronous online learning [57], participants in this study who were attending synchronous online courses did not report a significant positive impact of teaching presence on affective engagement. Therefore, further studies may explore the impacts of teaching presence on learners’ affective engagement across a variety of learning contexts.

In summary, the findings of this study confirm that SRL significantly and positively predicts learners’ perceived CoI and online learning engagement. Notably, SRL demonstrates a dual role by exerting substantial direct effects as well as indirect effects through various components of CoI. This highlights the nuanced impact of SRL in shaping engagement within online learning environments. Furthermore, the results highlight the varied effects of learners’ perceived CoI on enhancing online learning engagement. By focusing on cognitive, teaching, and social presence, educators can create dynamic and supportive online learning environments that foster meaningful engagement, promote learning outcomes, and cultivate a sense of community among learners.

6. Conclusions, Implications, and Limitations

This study examines the relationship between SRL, perceived CoI, and online learning engagement among CFL learners. This study found that SRL has a direct positive impact on learning engagement and indirectly promotes learning engagement through teaching, cognitive, and social presence. Additionally, this study underscores the varied effects of different CoI components on different dimensions of online learning engagement.

Firstly, SRL is crucial for online learning engagement. It not only significantly impacts social, cognitive presence, and teaching presence but also fosters community, cognitive exploration, and overall engagement in the online learning environment. These results provide implications for online teaching design aimed at promoting online learning engagement through SRL training. SRL is a cyclical process that includes planning, action, monitoring, evaluation, reflection, and planning [7]. To promote online learning engagement, more attention should be paid to teaching SRL strategies in addition to linguistic knowledge and skills. Teachers may provide support and guidance based on this cyclical SRL process. For instance, teachers may clarify learning objectives through a learning situation analysis in the learning planning stage. Through the log analysis of the teaching platform, it is possible to monitor learners’ dynamics. In addition, teachers and learners may periodically reflect on their learning progress, adjusting their learning goals and action plans for the next stage.

Secondly, social presence has been found to be extremely important in an effective online learning environment [25]. This study further highlights the importance of learners’ perceived social presence in enhancing their affective and social engagements. To enhance learners’ perceived social presence in online language classrooms, teachers may provide support and guidance to build an online learning community [15], such as by clarifying the concept of an online learning community or increasing the understanding of each learner to form a social bond, thereby radiating a sense of community. With the deepening of learner familiarity, the complexity of learning activities also increases from shallow to deep, gradually strengthening their in-depth participation in online classes.

Owing to the limited sample size of the current study, this study is unable to involve the four dimensions of online learning engagement in one coherent SEM model, which needs to be explored in future studies. Moreover, as previous studies suggested, SRL is a multifaceted and complex construct. This study, with a limited sample size, failed to examine the effects of different aspects of SRL on learners’ online learning engagement. Therefore, to gain a thorough understanding of the effects of SRL in the online learning environment, further studies with larger sample sizes are needed. Furthermore, the participants in the current study were mostly undergraduate students and intermediate-advanced learners (HSK level 4–5). In future studies, the relationships among variables may be examined across various learner groups, such as those with different cultural backgrounds and language proficiency, to gain a deeper understanding of online learning engagement.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fujian Provincial Social Science Foundation, grant number FJ2021C055; the Center for Language Education and Cooperation of Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, grant number 21YH47D.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics consideration was involved from the Funding Committees of Fujian Provincial Social Science Foundation and the Center for Language Education and Cooperation of Ministry of Education of the People’s Re-public of China, and the study was granted approval (Approval number: FJ2021C055, Approval date: 20 May 2021; Approval number: 21YH47D, Approval date:10 July 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| Construct | Item | Factor Loading |

| Cognitive engagement | I keep trying my best even when it is hard. | 0.763 |

| I think about different ways to solve problems in my work. | 0.782 | |

| I try to connect new learning to the things I already learned before. | 0.762 | |

| Behavioural engagement | I take notes over readings, PowerPoint Slides, or video lectures. | 0.630 |

| I can pay attention and listen carefully. | 0.899 | |

| I participate in all the activities. | 0.755 | |

| Affective engagement | I am looking forward to the next class. | 0.827 |

| I have fun in the class | 0.823 | |

| I feel good while I am in the class. | 0.887 | |

| I enjoy learning new things. | 0.654 | |

| Social engagement | I get to know other students in the class. | 0.672 |

| There is a collaborative climate in this course. | 0.825 | |

| I help fellow students. | 0.682 | |

| Cognitive presence | Online discussions are valuable in helping me appreciate different perspectives. | 0.758 |

| Learning activities helps me construct explanations/solutions. | 0.809 | |

| Combining various information helps me answer questions raised in course activities. | 0.835 | |

| Reflection on course content and discussions help me better understand the course. | 0.853 | |

| Social presence | I feel comfortable interacting with other course participants. | 0.801 |

| I feel that my point of view is acknowledged by other course participants. | 0.835 | |

| I feel comfortable participating in the course discussions. | 0.892 | |

| I feel comfortable conversing through the online medium. | 0.820 | |

| Teaching presence | The instructor clearly communicates important course topics. | 0.880 |

| The instructor provides feedback in a timely fashion. | 0.829 | |

| The instructor helps to keep course participants engaged and participating in productive dialogue. | 0.859 | |

| The instructor provides clear instructions on how to participate in course learning activities. | 0.914 | |

| Self-regulated learning | I make sure to study on a regular basis | 0.821 |

| I allocate extra studying time for my online courses because I know it is time-demanding. | 0.733 | |

| I summarize my learning in online courses to examine my understanding of what I have learned. | 0.802 | |

| I try to take more thorough notes for my online courses because notes are even more important for learning online than in a regular classroom. | 0.689 | |

| I know where I can study most efficiently for online courses. | 0.767 |

References

- Ministry of Education. Available online: http://en.moe.gov.cn/ (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Chineseplus Homepage. Available online: https://www.chineseplus.net/home (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Ministry of Education. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xxgk/xxgk_jyta/yuhe/202208/t20220803_650543.html (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Wang, W.; Guo, L.; He, L.; Wu, Y.J. Effects of social-interactive engagement on the dropout ratio in online learning: Insights from MOOC. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019, 38, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astin, A.W. Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. J. Coll. Stud. Pers. 1984, 25, 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.P.; Yang, L.Y.; Zhang, J.; Gan, Y.J. Academic self-concept, perceptions of the learning environment, engagement, and learning outcomes of university students: Relationships and causal ordering. High. Educ. 2022, 83, 809–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory Pract. 2002, 41, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Anderson, T.; Archer, W. Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2000, 2, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Lai, C.; Gao, X. The teaching and learning of Chinese as a second or foreign language: The current situation and future directions. Front. Educ. China 2020, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiver, P.; Al-Hoorie, A.H.; Vitta, J.P.; Wu, J. Engagement in language learning: A systematic review of 20 years of research methods and definitions. Lang. Teach. Res. 2024, 28, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andujar, A.; Medina-López, C. Exploring new ways of eTandem and telecollaboration through the WebRTC protocol: Students’ engagement and perceptions. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2019, 14, 200–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaman, U.; Sert, O. Development of L2 interactional resources for online collaborative task accomplishment. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2017, 30, 601–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.H.; Castañeda, D.A. Motivational and affective engagement in learning Spanish with a mobile application. System 2019, 81, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, C.; Philp, J.; Nakamura, S. Learner-generated content and engagement in second language task performance. Lang. Teach. Res. 2017, 21, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusharraf, N.M.; Bailey, D. Online engagement during COVID-19: Role of agency on collaborative learning orientation and learning expectations. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2021, 37, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, B.; Lai, C. Analysing learner engagement with native speaker feedback on an educational social networking site: An ecological perspective. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2024, 37, 114–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, L.; Hong, J.C.; Cao, M.; Dong, Y.; Hou, X. Exploring the role of online EFL learners’ perceived social support in their learning engagement: A structural equation model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 1703–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Liang, J.C.; Chai, C.S.; Chen, X.; Liu, H. Comparing high school students’ online self-regulation and engagement in English language learning. System 2023, 115, 103037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Duan, P.; Yu, Z. Teacher support, academic engagement and learning anxiety in online foreign language learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024. early version. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R.C.; Hamre, B.K.; Allen, J.P. Teacher-student relationships and engagement: Conceptualizing, measuring, and improving the capacity of classroom interactions. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement, 1st ed.; Christenson, S.L., Reschly, A.L., Wylie, C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, L. Task preference, affective response, and engagement in L2 use in a US university context. Lang. Teach. Res. 2017, 21, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvelä, S.; Renninger, K.A. Designing for learning: Interest, motivation, and engagement. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, 1st ed.; Sawyer, K., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 668–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doo, M.Y.; Bonk, C.J.; Heo, H. Examinations of the relationships between self-efficacy, self-regulation, teaching, cognitive presences, and learning engagement during COVID-19. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2023, 71, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jin, T.; Edirisingha, P.; Zhang, X. School-aged students’ sustainable online learning engagement during COVID-19: Community of inquiry in a Chinese secondary education context. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Saab, N.; Admiraal, W. Do learners share the same perceived learning outcomes in MOOCs? Identifying the role of motivation, perceived learning support, learning engagement, and self-regulated learning strategies. Internet High. Educ. 2023, 56, 100880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Cleveland-Innes, M.; Fung, T.S. Exploring causal relationships among teaching, cognitive and social presence: Student perceptions of the community of inquiry framework. Internet High. Educ. 2010, 13, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R. Communities of inquiry in online learning. In Encyclopedia of Distance Learning, 1st ed.; Rogers, P.L., Berg, G.A., Boettcher, J.V., Howard, C., Justice, L., Schenk, K.D., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 352–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.H.; McIsaac, M. An examination of social presence to increase interaction in online classes. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2002, 16, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.J.; Tu, C.H.; Tankari, M.; Özkeskin, E.E.; Harati, H.; Miller, A. A predictive study of students’ social presence and their interconnectivities in the social network interaction of online discussion board. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2022, 5, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, P.; Bidjerano, T. Community of inquiry as a theoretical framework to foster “epistemic engagement” and “cognitive presence” in online education. Comput. Educ. 2009, 52, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyol, Z.; Garrison, D.R. Understanding cognitive presence in an online and blended community of inquiry: Assessing outcomes and processes for deep approaches to learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2011, 42, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doo, M.Y.; Bonk, C.J. The effects of self-efficacy, self-regulation and social presence on learning engagement in a large university class using flipped Learning. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2020, 36, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galikyan, I.; Admiraal, W. Students’ engagement in asynchronous online discussion: The relationship between cognitive presence, learner prominence, and academic performance. Internet High. Educ. 2019, 43, 100692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Academic studying and the development of personal skill: A self-regulatory perspective. Educ. Psychol. 1998, 33, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, R.S.; van Leeuwen, A.; Janssen, J.; Kester, L. Exploring the link between self-regulated learning and learner behaviour in a massive open online course. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2022, 38, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Hong, J.C.; Dong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Fu, Q. Self-directed learning predicts online learning engagement in higher education mediated by perceived value of knowing learning goals. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2023, 32, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.; Triglianos, V.; Hauff, C.; Houben, G.-J. SRLx: A personalized learner interface for MOOCs. In Lifelong Technology-Enhanced Learning, 1st ed.; Pammer-Schindler, V., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., Drachsler, H., Elferink, R., Scheffel, M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizilcec, R.F.; Pérez-Sanagustín, M.; Maldonado, J.J. Self-regulated learning strategies predict learner behavior and goal attainment in massive open online courses. Comput. Educ. 2017, 104, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhari, S.C.; Fadjarajani, S.; Rosali, E.S. SEM-PLS Analysis to investigate the relationship between self-regulated learning, family support and learning motivation on students’ learning engagement. J. Educ. Res. Eval. 2023, 7, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.R.; Cao, C.H. Exploring relationship among self-regulated learning, self-efficacy and engagement in blended collaborative context. SAGE Open. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. MOOC learners’ demographics, self-regulated learning strategy, perceived learning and satisfaction: A structural equation modeling approach. Comput. Educ. 2019, 132, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.H.; Kim, Y.; Choi, D. The effect of self-regulated learning on college students’ perceptions of community of inquiry and affective outcomes in online learning. Internet High. Educ. 2017, 34, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilis, S.; Yıldırım, Z. Investigation of community of inquiry framework in regard to self-regulation, metacognition and motivation. Comput. Educ. 2018, 126, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Language Council International, Confucius Institute Headquarters. Xin Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi Dengji Dagang [Syllabus for New Chinese Proficiency Test], 1st ed.; Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dixson, M.D. Measuring student engagement in the online course: The online student engagement scale (OSE). Online Learn. 2015, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, G.; Perrucci, V.; Cacciamani, S.; Zumbo, B.D. Development of a scale of sense of community in university online courses. Distance Educ. 2018, 39, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, L.; Lan, W.Y.; To, Y.M.; Paton, V.O.; Lai, S.L. Measuring self-regulation in online and blended learning environments. Internet High. Educ. 2009, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, F.N. Comparison of different estimation methods used in confirmatory factor analyses in non-normal data: A Monte Carlo study. Int. Online J. Educ. Sci. 2019, 11, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmines, E.G.; McIver, J.P. An introduction to the analysis of models with unobserved variables. Polit. Methodol. 1983, 9, 51–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.; Richardson, J.C. Predictive effects of undergraduate students’ perceptions of social, cognitive, and teaching presence on affective learning outcomes according to disciplines. Comput. Educ. 2021, 161, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, P.; Bidjerano, T. Cognitive presence and online learner engagement: A cluster analysis of the community of inquiry framework. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2009, 21, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yao, L.; Duan, C.; Sun, X.; Niu, G. Teaching presence promotes learner affective engagement: The roles of cognitive load and need for cognition. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 129, 104167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntaner-Mas, A.; Vidal-Conti, J.; Sesé, A.; Palou, P. Teaching skills, students’ emotions, perceived control and academic achievement in university students: A SEM approach. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 67, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadatmand, M.; Uhlin, L.; Hedberg, M.; Åbjörnsson, L.; Kvarnström, M. Examining learners’ interaction in an open online course through the community of inquiry framework. Eur. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2017, 20, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).