Abstract

The massive relocation of international students calls for a thorough investigation of diverse difficulties faced by them, among which language-related barriers are reported to have serious consequences. The main goal of this research is to investigate accent-related challenges as barriers to comprehension and effective communication faced by international students in the United Kingdom (UK), along with the factors that helped or could help the students in terms of having better experiences. The scope of this study is limited to native British accents. The study relies on data collected to analyse the impact of native-accented speech, both qualitatively and quantitatively, on the listening experiences of currently enrolled or recently graduated international students in a British university. The underlying mixed-method approach is comprised of a survey and an interview. Analysis of data collected from the survey (n = 33 participants) revealed that 42% of the participants considered native-accented speech as the biggest factor affecting their listening comprehension. This is followed by a fast speech rate, which was selected by 36% of the participants. Regarding mitigation of the difficulties, participants showed mixed responses in terms of adopting various strategies. During the interview, participants (n = 6) shared their listening comprehension experiences, particularly those encountered during the initial months after their arrival in the UK. The results obtained are potentially useful in terms of students’ support, English as a Second Language (ESL) curriculum design, English language teachers’ training and establishing learning pedagogies.

1. Introduction

This research is centred on international students’ educational experiences abroad. International students, such as those in this study, are those students who travel out of their home countries for tertiary study and whose previous cultural and linguistic experiences differ from the traits of the host country where they are going. Students’ experiences inside and outside of the classroom contribute to their educational development. Research findings have concluded that a common international student deals with language and cultural-related challenges, but despite that, they should succeed academically due to their motivation and efforts [1].

Recent years witnessed a tremendous increase in international students being admitted into courses in English-speaking countries. Given the international, socio-economic and geo-political situations, this trend is anticipated to continue. Thus, Higher Educational Institutions (HEIs) have set as one of their major priorities to internationalise their campuses. The driving force for the increase of international students in English-speaking countries is the conviction that getting a degree from these countries is a good investment for their future careers. Moreover, it is also expected that this educational journey will enrich their English language skills [2]. Consequently, there is a wider cultural diversity among HEIs across the globe. The presence of international students enriches classroom discussions since they share stories and experiences from different cultures [3].

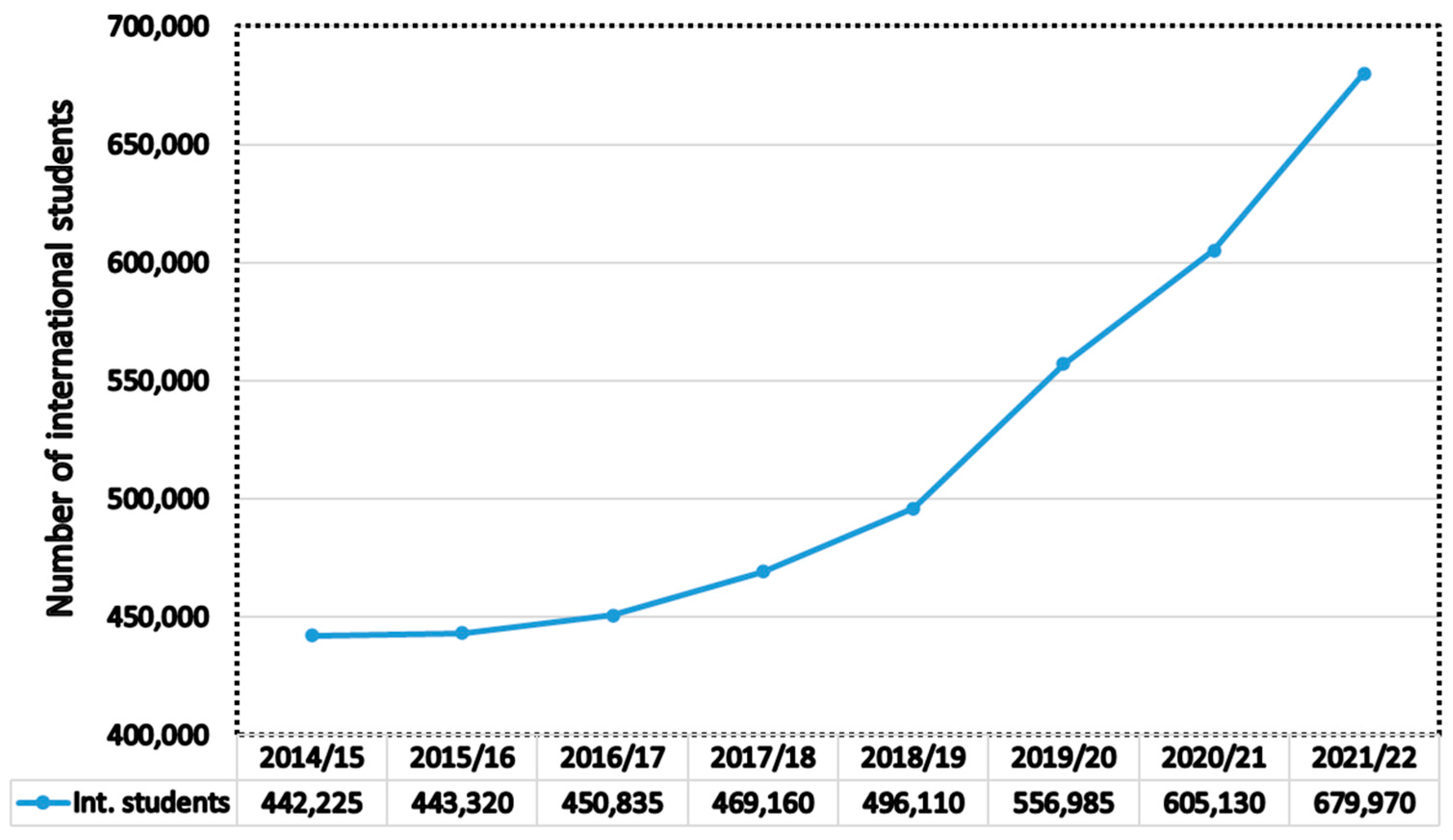

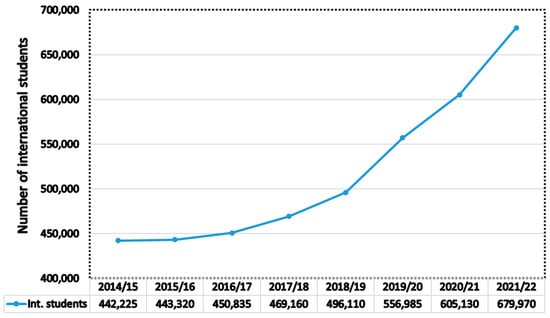

The UK, being a hub of exceptional quality and a standard of education and professional training, is highly popular among international students [4]. During the last decade, the number of students coming to the UK to pursue higher education has increased beyond expectations. The UK met its 600,000 international students target a decade earlier than was originally hoped [5]. Based on Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) data corresponding to international students enrolled in Higher Education (HE) in the UK, Figure 1 shows statistics from the academic year 2014/15 until 2021/22. An increasing trend in the recruitment of international students is clearly seen. The academic year 2021–22 witnessed around 680,000 enrolments of international students in the UK, with an increase of 12% compared to the previous year. While these students belong to various parts of the globe, China, India and Nigeria are the top three countries of origin for international students.

Figure 1.

HE students’ enrolments by domicile—plot based on data collected from the HESA.

A huge number of international students offers notable financial, social, cultural and academic benefits to a host country in general and to the UK in particular. However, international students face numerous challenges as they begin living in a new environment. Among their adjustment issues, language-related difficulty has been ranked as the main one, interfering in international students’ academic and social lives [6].

Language proficiency is strongly linked with the personal, academic, social and cultural development of international students. Among the four linguistic skills, listening typically takes up to 40–50% of the time we use a language, thus highlighting its vital importance [7]. Despite this, listening has been the least investigated of all the four language skills [8], even though listening comprehension is imperative in the learning of a second or foreign language because of the aspects it covers. Thus, listening is a complex skill that requires multiple cognitive operations in the process of comprehension and is affected by a variety of factors [9]. Thus, difficulties in listening comprehension deserve particular attention. Among the listening comprehensive difficulties, understanding diverse accents is reported to be the most common cause [10] and has implications in both academic [11] and social lives [12]. That is why this research focuses on the issue of challenges related to understanding accents. It attempts to investigate that difficulties in understanding accents can become a big language barrier to effective communication in terms of academic development and social adjustment.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of previous research on the study-abroad experience of international students. Section 3 presents the research design, which includes research methodology and participant selection criteria. Moreover, ethical aspects including participants’ consent and potential risks are highlighted, as well as the data collection procedures. Section 4 discusses the findings obtained to investigate the listening comprehension difficulties faced by international students, particularly during their initial time in the UK. Finally, Section 5 presents the conclusion of the research and emphasises its potential in terms of enhancing international students’ experience.

2. Literature Review

Education literature reports some relevant state-of-the-art works investigating the effect of accents on the experience of international students. Research [13] investigated the impact of the Liverpool English accent on international students’ listening experiences in a study-abroad context during a one-year programme. The research explored the previous training experience of the students in terms of preparing them for understanding a second language (L2), which has been limitedly addressed [14]. The participants were 102 international MA Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) students aged 20–35 (mostly Chinese) enrolled at the University of Liverpool. A mixed methods approach was followed, which consisted of a questionnaire (n = 92), rated scale-based listening experiences (n = 11), semi-structured interviews (n = 11) and spoken interaction journals (n = 21). It was found that lack of accent familiarity was the biggest factor in listening comprehension difficulties of international students, followed by speed of speech. To mitigate the listening difficulties, most of the students either requested speaker repetition or a change in their speech rate to gain understanding. Moreover, the participants were asked to respond on the time they took to understand the accents. Results show that more than 70% of the participants took 1–6 months to get used to listening to and understanding the Liverpool English accent. Two participants could not manage to understand Liverpool English, even after 12 months. Data collected from the participants indicate that 88% of the respondents mentioned that spending time with locals helped them to better understand the Liverpool English accent. It can therefore be assumed that interaction with native speakers is an important factor in gaining listening proficiency. Therefore, language institutions should provide more opportunities for learners to have a study-abroad experience so that they can develop self-confidence in using the target language.

Research [15] reported on the difficulties experienced by Chinese international students during their adaptation to English academic communities. These difficulties were related to understanding lectures, verbally answering their teachers’ questions and participating in class discussions. The results of this study suggest that online courses may help enhance the language proficiency required in academic contexts since they provide interactive user forums to encourage student participation. The themes identified by this research included accent, speed, new vocabulary, interactive communication, academic conventions, etc. It is implied that these linguistic problems are due to insufficient exposure and practice prior to moving to English-speaking environments. Therefore, Chinese international students need to have more cross-cultural interactions with native speakers or local people from the host country in and outside classrooms. Grammar translation remains the predominant teaching approach in China, despite some changes towards the development of listening and speaking skills. These results support the idea that one of the most important issues HEIs need to address is a significant change in foreign language assessment. The new criteria should be more oriented towards the completion of authentic tasks so that learners develop communicative competence.

Another research study [16] qualitatively analysed various challenges experienced by international students in Montreal, Canada. These challenges were related to the English language and other academic aspects in addition to social, personal and cultural problems faced by the students. The research tool consisted of flexible semi-structured interviews with ten participants. Many participants reported experiencing language-related issues in the context of their university courses, even though only a small number of individuals acknowledged linguistic challenges encountered outside of the classroom. These results suggest that English courses tailored for academic language use should be beneficial to students including those with advanced English proficiency. Furthermore, credit-bearing courses should be offered to international students so that they feel motivated to register, despite their hectic academic schedules. Participants emphasised the need to have a face-to-face language support or language exchange program. These findings suggest that weekly conversation clubs with native English-speaking volunteers would be beneficial since these programmes enable linguistic and cultural exchange. One limitation found in this study is the small sample size of participants. Furthermore, the results deduced cannot be considered representative of the international student population of this Canadian university due to the limited number of nationalities involved.

Another study [12] explored the issues faced by international students at the tertiary level in Australia due to accented English at two levels: (i) their own accent as a communication barrier and (ii) their difficulty in understanding other people’s accents. Considering students’ interactions in educational and social settings, this study utilised a mixed methods approach. Moreover, a survey and group interviews were employed to examine their accent-related challenges, perceptions and concerns, as well as their mitigation strategies to address those issues. The study included 182 participants from three major universities. The results indicated that even though participants had an effective command of English, they faced educational and social issues due to first language (L1) and L2-accented English. Their foreign accent caused adverse attitudes and prejudice towards them. These findings add to the body of research that already shows that, both in official settings and in casual interactions, people use accents to draw conclusions about others. In common speech, one says, ‘a person has an accent,’ highlighting the distinction from the presumptive norm of non-accent, as though accents are exclusive to foreigners. Furthermore, these results may be taken to indicate that acquiring an intelligible accent should be a more realistic goal of spoken language courses in teaching English as a Foreign Language (EFL). Thus, future L2 speakers can be more easily understood in international settings. Students appeared to have more trouble understanding Australian English in social contexts than in classrooms. Their top three mitigation strategies were repetition, paraphrasing and speaking more clearly. These results provide some tentative initial evidence that international students have limited social interaction with L1 speakers, which could contribute to losing confidence while speaking English. The study also reports some limitations. Sample bias may result from the snowball sampling employed, as the participants are chosen based on recommendations. For example, the sample may be skewed since participants tend to recommend people who share common traits or experiences with them.

In another study [17], it has been reported that students’ English pronunciation is influenced by the local language and dialects of nations where English is not widely spoken. Variations in body language and expressions can also be brought by local customs. Students do not learn in an environment that requires the same vocabulary, pronunciation, writing style or usage as the UK. Furthermore, students in these nations are typically not instructed by native speakers. In fact, perceptions about Westerners and their habits impact language learning even in situations where there are native speakers. Each of these elements has an impact on the level of English language competency of students who come to the UK for higher education.

According to research [18], foreign students found it challenging to adjust to diverse versions of spoken English and English accents in the sociocultural and academic context of their host nation, as opposed to the stereotypically “posh” English they had been exposed to in the media. They had trouble with the accents of local people and foreign teaching staff, colloquial language, specialised vocabulary and speech rate. The sample space in this research consisted of twenty-three students enrolled in a one-year Master’s course at a British university. Most of the participants in this study were L2 English speakers. This investigation yielded two conclusions. Firstly, it seemed that most of the participants faced greater difficulties adjusting to the academic than to the socio-cultural environment during the initial stages of their sojourn, which brought significant psychological stress. Secondly, the primary cause of their difficulties in adapting to both academic and socio-cultural contexts was frequently attributed to their unfamiliarity with the various English accents. These results should be considered when planning and implementing academic workloads across host universities so that the learning journey does not become a continuous source of stress, particularly for international students. These findings suggest that international students may benefit from a time management course as part of their core subjects. Furthermore, there should be training in listening programmes that are specially designed to get more familiar with the local accent.

There is a dearth of research in the ‘Higher Education’ literature that looks in-depth at how international students join the academic community of practice and adjust to British society through the lens of language experience. Thus, barriers to listening comprehension arising from understanding British accents with a focus on international students have not been fully explored and require special attention. Given this research gap, the present research attempts to examine whether British accents have any significant effect on international students’ listening comprehension in academic and social contexts. Also, it explores how students deal with consequences arising due to non- (or less) familiarity with accents, which constrain them from grasping the intended meaning. To the best of the author’s knowledge, no study has investigated the holistic view of university international students’ listening difficulties in terms of diverse East Yorkshire accents.

This study does not attempt to underestimate non-native English accents when choosing to investigate only the impact of the difficulties in understanding British accents. It is acknowledged that non-native English accents are representative and are authentic varieties to which English as a Second Language (ESL) learners need to be eventually exposed. It is understood that many international students encounter numerous difficulties when listening to native and non-native varieties of English. However, the focus of this study is on native British accents since international students are expected to be somehow more familiar with them. Moreover, many learners still prefer to have a native speaker accent as their ultimate goal [19].

3. Research Design

This research involves a pragmatic paradigm considering the multi-faceted dimensions of the research problem. This enhances the reliability of the investigation and its results [20] and allows a deeper comprehension of a study compared to employing only qualitative or quantitative approaches.

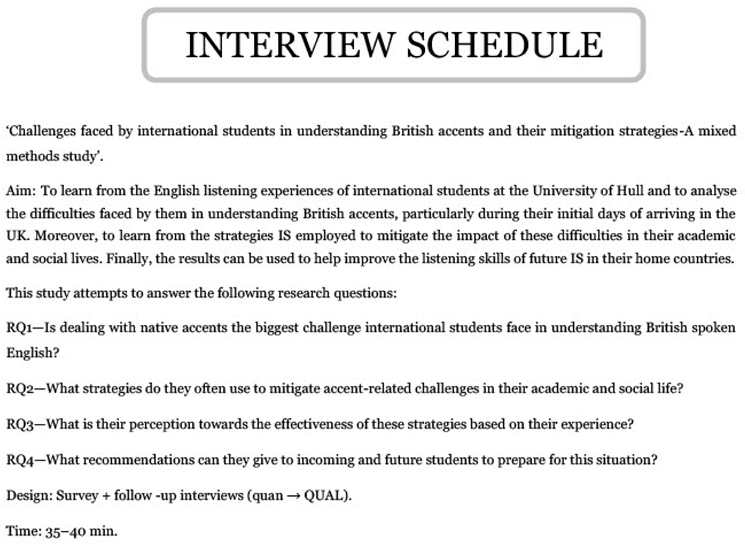

A qualitative approach was mainly adopted to deal with the world of human experience. This research was carried out through a survey and a follow-up interview. In other words, this procedure represents a sequential method described as “quan →QUAL” [21].

The research questions of the present study are listed in Table 1, given below.

Table 1.

Research questions in the present study.

3.1. Instruments

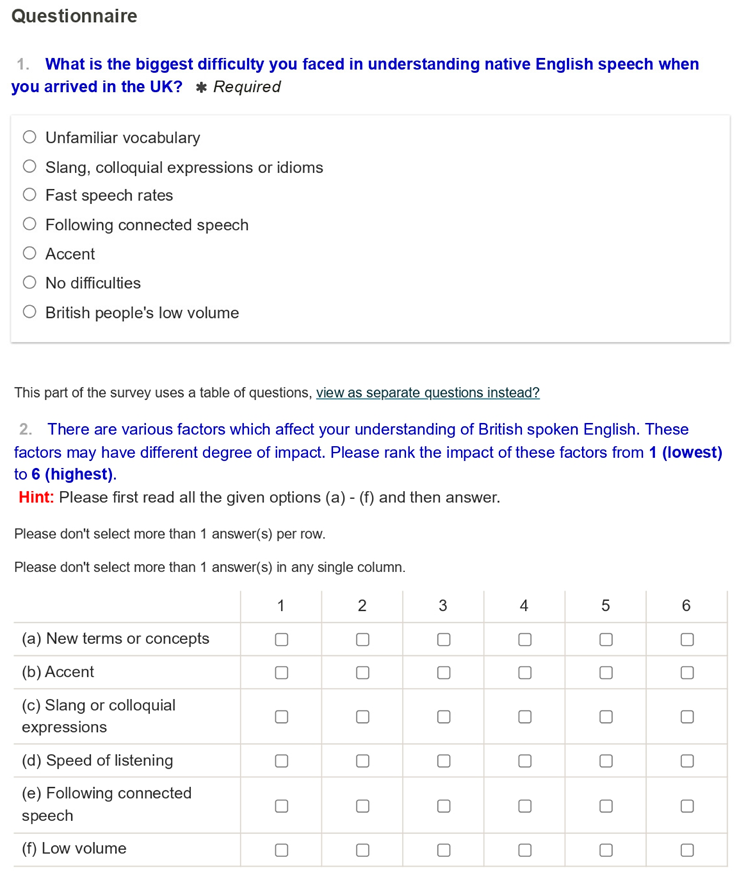

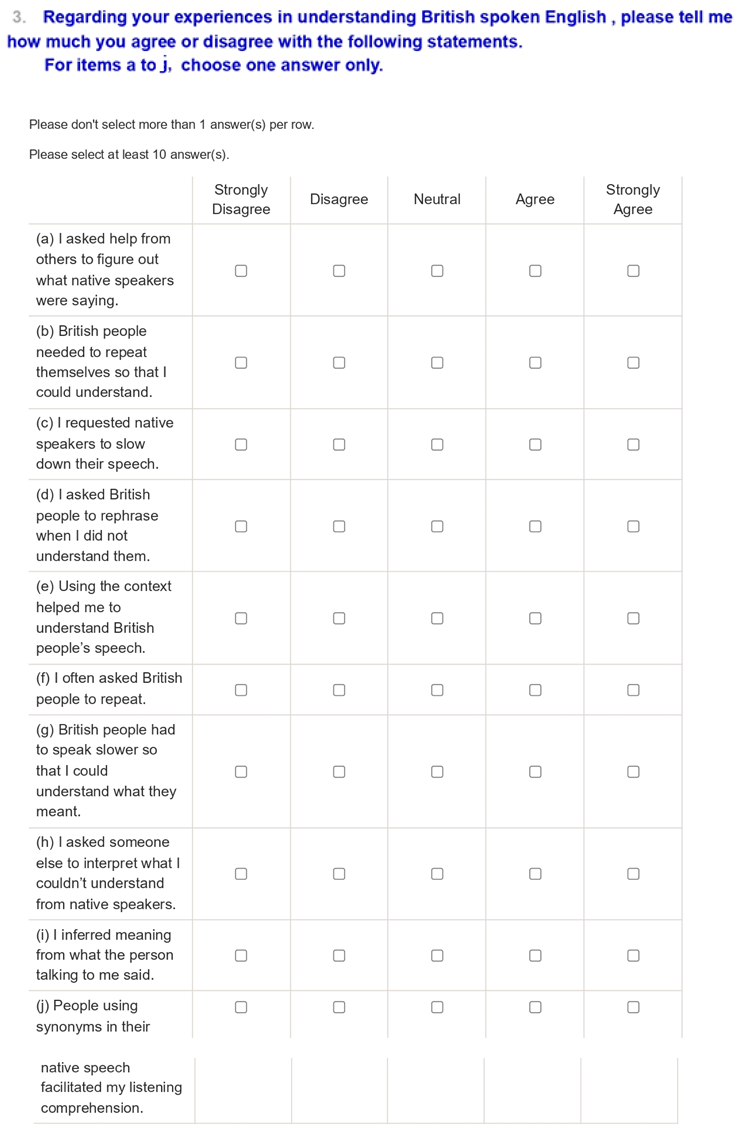

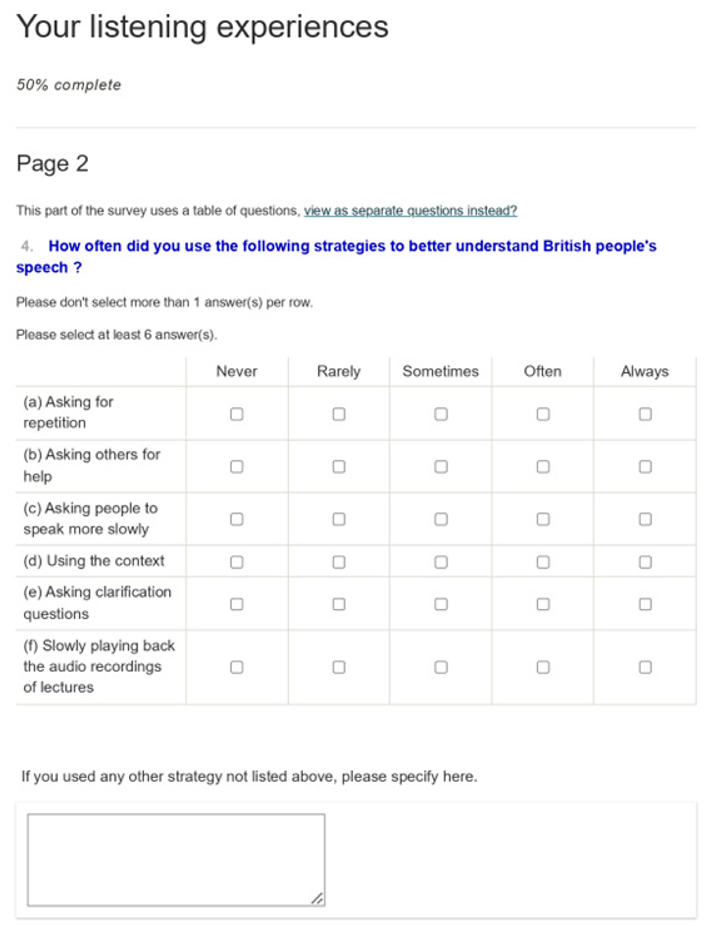

The two research instruments in this mixed methods study included an online survey and semi-structured interviews. There were questions specific to academics (such as in the questionnaire sentence (Q4f) and specific to social life (e.g., Q13–Q15 in the interviews). However, the research instruments had elements that are applicable to both academic as well as social life. Additionally, the flexibility in the questionnaire has been enhanced by having an open-ended question, (Q4a): “If you used any other strategy not listed above, please specify here”. This proved to accommodate the collection of valuable subjective and potentially useful information related to both academics and social interaction. The research instruments are detailed below:

3.1.1. Online Survey

For this paper, the term ‘questionnaire’ is used to refer to the set of questions to collect data from participants, while the term ‘survey’ refers to the method that uses this data, evaluates it and finally draws conclusions.

A questionnaire was created and administered by JISC online surveys. The guiding factors in designing the questionnaire were vocabulary, prior knowledge, speech rate, input and accent. The questions were formulated with reference to [10,22], which concluded that L2 listeners’ difficulties are mostly due to irrelevant topics, unknown vocabulary, unfamiliar accents, etc.

There were twelve questions in total in the questionnaire comprised of closed-ended questions, except for Q4a, and demographic questions. Table 2 summarises the type of questions asked in the survey. The questionnaire is appended in Appendix A.

Table 2.

Summary of the online questionnaire.

Reliability in the questionnaire was increased by having questions confirming other parts of it. For example, Q1 and Q2 were strongly interlinked and thus their responses could be compared. In Q3, multi-item scales were used, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Description of multi-items in Q3 of the questionnaire (see Appendix A).

3.1.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

Following the survey, the researcher interviewed a smaller group of students (n = 6). The interview was comprised of 12 questions which were prepared in detail as this tool served as the main research instrument. They included some questions specifically written for the present study, while some other questions were designed using previously reported studies [13]. Complete interview questions are appended in Appendix B. Codes have been assigned to participants to protect their identity while reporting the interview data. The two research instruments complemented each other. The survey addresses RQ1 and RQ2 while the interview addresses RQ1 to RQ4.

3.2. Piloting and Validation

The data collection tools were piloted prior to being administered to the whole sample to check if they were direct and simple and to guarantee that the research would be more accurate. Moreover, during the piloting phase, it was evaluated whether the answers provided addressed the research questions. The goal of the pilot study was to increase the validity, reliability and clarity of the research instruments. Minor adjustments were made to enhance clarity and to encourage participants to elaborate more on their answers.

3.3. Sampling

The present study used convenience sampling and purposive sampling for the survey and the interview, respectively. For the survey, the choice of convenience sampling was primarily driven by constraints in terms of the availability of participants. The convenience sample is mainly made up of the researcher’s class fellows, MA TESOL students at a British university.

For the semi-structured interview, purposive sampling was employed to deal with the issue of the small sample size of the interviewees, an area in which qualitative research shows vulnerability. Purposive sampling is one strategy for addressing this problem. As advised [21], this method can be made more ethical if a preliminary questionnaire (appended in Appendix A) in the research is included so that it serves as a tool to systematically choose the participants for the qualitative phase that follows.

3.4. Participants

The participants are current or recently graduated international students from a British university. Most of them speak English as a second or foreign language. During the admission procedure, the students successfully evidenced that they fulfilled at least the minimum English language requirement criteria laid down by the University. Moreover, at the time of taking part in this research, all participants had spent at least a ten-month sojourn living and studying in the UK.

Table 4 presents the participants who contributed to the survey. In total, 37 participants submitted the questionnaire. However, four participants had to be excluded. Participants for the interview were selected based on the outcome of a representative initial questionnaire. Twelve out of 33 participants agreed to be interviewed, which is certainly an encouraging response. However, given the focus of the present study and to be in line with research questions, all the respondents (7 out of 12) who chose accent as the biggest difficulty to their listening comprehension were invited to participate in the interview. Out of 7, 6 participants finally gave the interview. The last column of Table 4 lists the participants who took part in the interview.

Table 4.

Demographic information about participants.

3.5. Data Collection and Analysis

All the interviews were carried out individually in English. The interview session started after obtaining informed consent from the participants and it lasted around 30 min. Each interview was recorded and transcribed word by word for subsequent analysis.

Even though the present study is based on a mixed methods approach, quantitative and qualitative data analyses were conducted independently. Analysis of quantitative and qualitative data was based on descriptive statistics and content analysis, respectively. Excel was also used to compare data sets, analyse standard deviation, create graphs and diagrams and recognise anomalous data. For analysis of the interview data, all transcripts were thematically analysed. A three-stage coding process [21] was followed.

4. Results and Discussion

The findings from this study are based on responses collected from two research tools: a survey and an interview. The results are sequentially presented by addressing each research question in detail.

4.1. Research Question 1 (RQ1)

RQ1 is “Is dealing with native accents the biggest challenge international students face in understanding British spoken English?”. The data used to respond to this research question come from survey responses followed by interview data.

The purpose of the survey was to find out the main difficulty of listening comprehension encountered by international students dealing with British spoken English. The participants (n = 33) were quite diverse in terms of gender, country of origin and prior exposure to the English language. The randomly invited sample for the survey turned out to be gender-balanced, as illustrated in Table 4. A relationship between gender and listening comprehension difficulties could not be determined. Therefore, this parameter was not relevant to any research question.

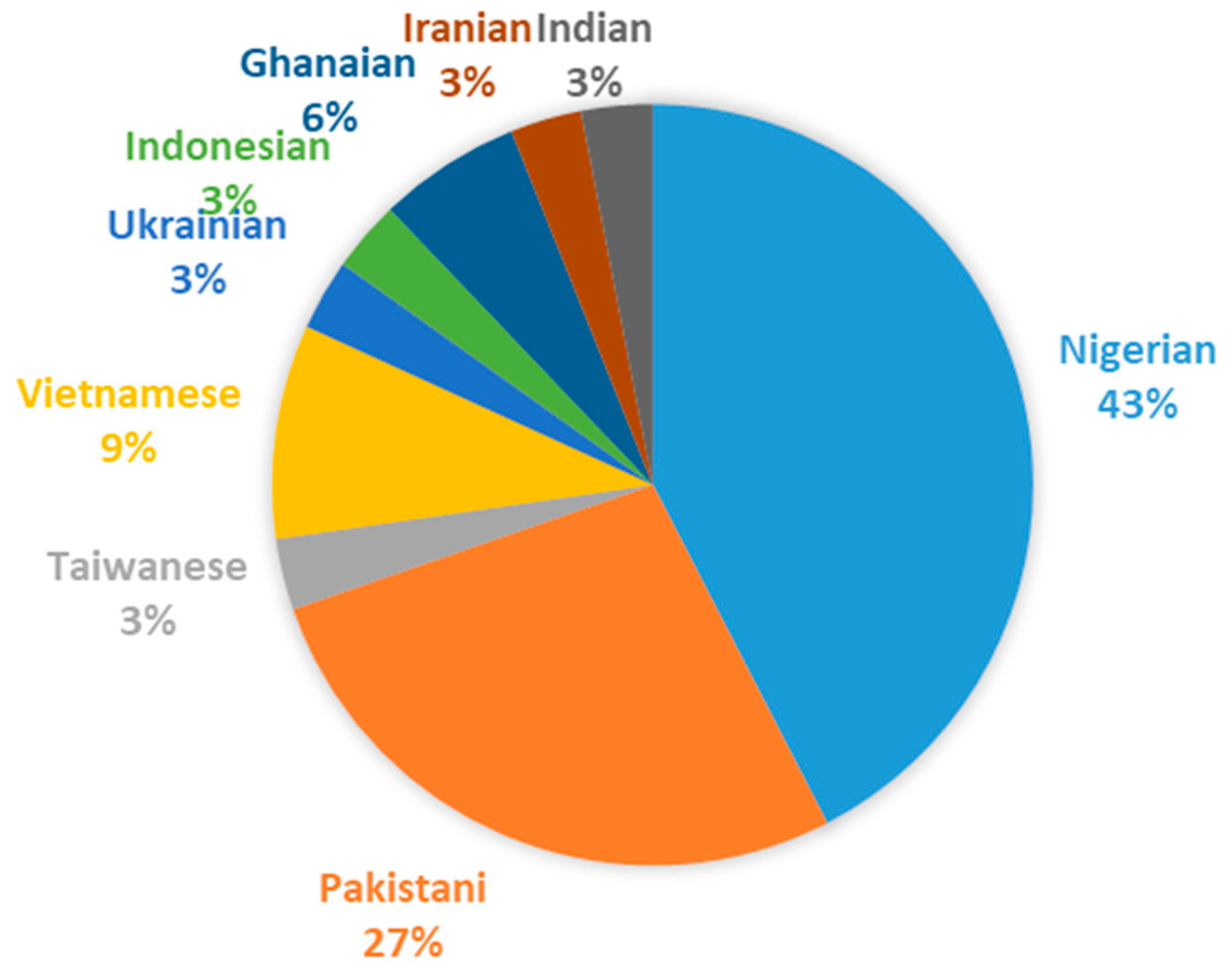

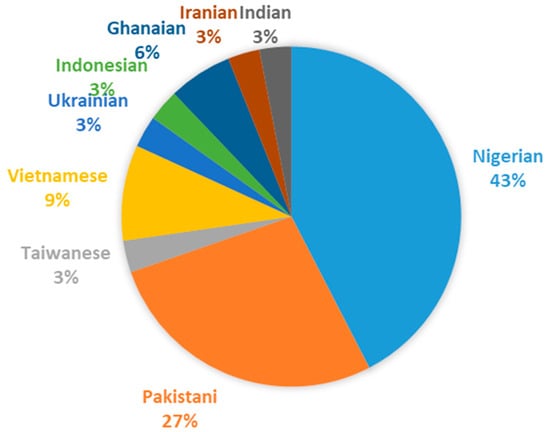

There was also a great diversity with respect to the countries of origin of participants. They were from 9 different countries, though 70% of participants were from Nigeria and Pakistan. The diversity in participants’ nationalities reflected a wide range of first language and cultural backgrounds. Figure 2 shows a pie chart illustrating the nationalities of participants.

Figure 2.

Survey participants’ nationalities—Q10.

Furthermore, the survey was intended to investigate the kinds of challenges faced by participants in listening comprehension, along with their degree of impact. The English language background of participants was assessed by asking them if English was their second language. It was found that English was the second language for more than 90% of participants.

It is interesting to note here that around 35% of those students from ESL countries indicated accent as the biggest factor in their listening comprehension difficulties. On the other hand, almost 72% of students from EFL countries mentioned that accent was the biggest barrier to understanding native English speech. Analysing the results from these two groups of English users, a notable difference has been observed that is worthy of further research. Even though the sample size of this research is small, a qualitative study could be carried out to investigate why native accents may have a bigger impact on EFL speakers.

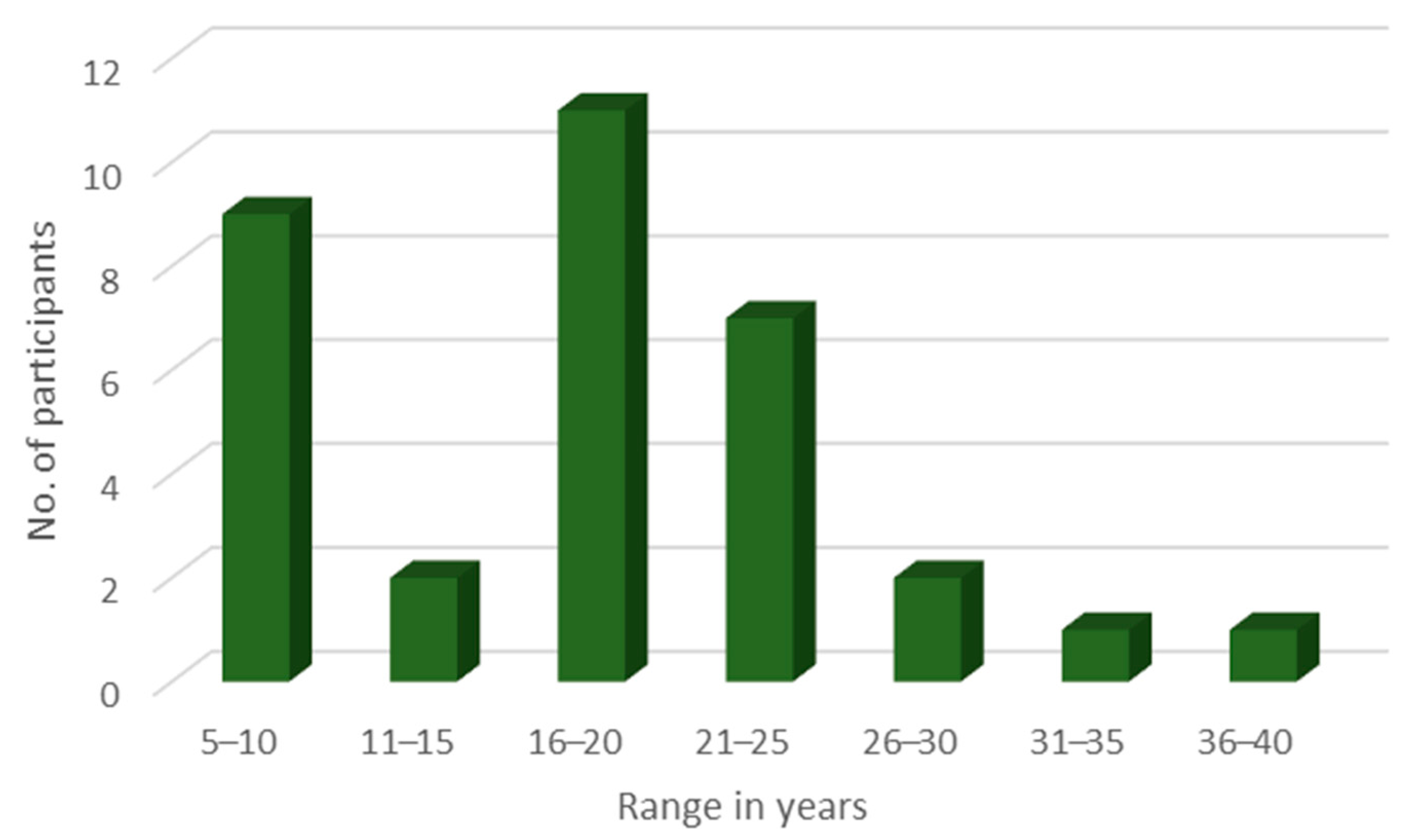

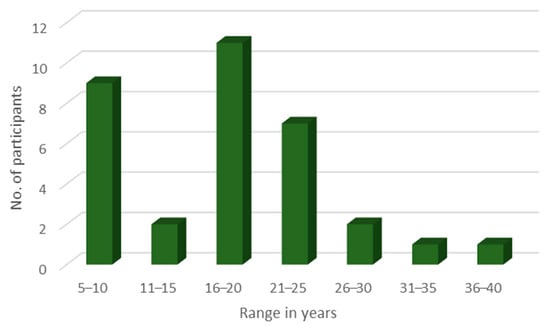

To investigate the impact of prior studies (English as a medium of instruction) on the listening proficiency of participants, they were requested to specify how long they had studied English in their home countries. Corresponding results are illustrated in Figure 3, which shows a huge variance in participants’ prior studies in English ranging from 5–40 years. Two participants having 10 years and 20 years of prior studies in English reported no difficulty in listening comprehension. Except for these two participants, it was found that, generally, the number of years of English studies was not a function of the listening proficiency of the participants.

Figure 3.

Participants’ prior studies in English in years (survey result)—Q6.

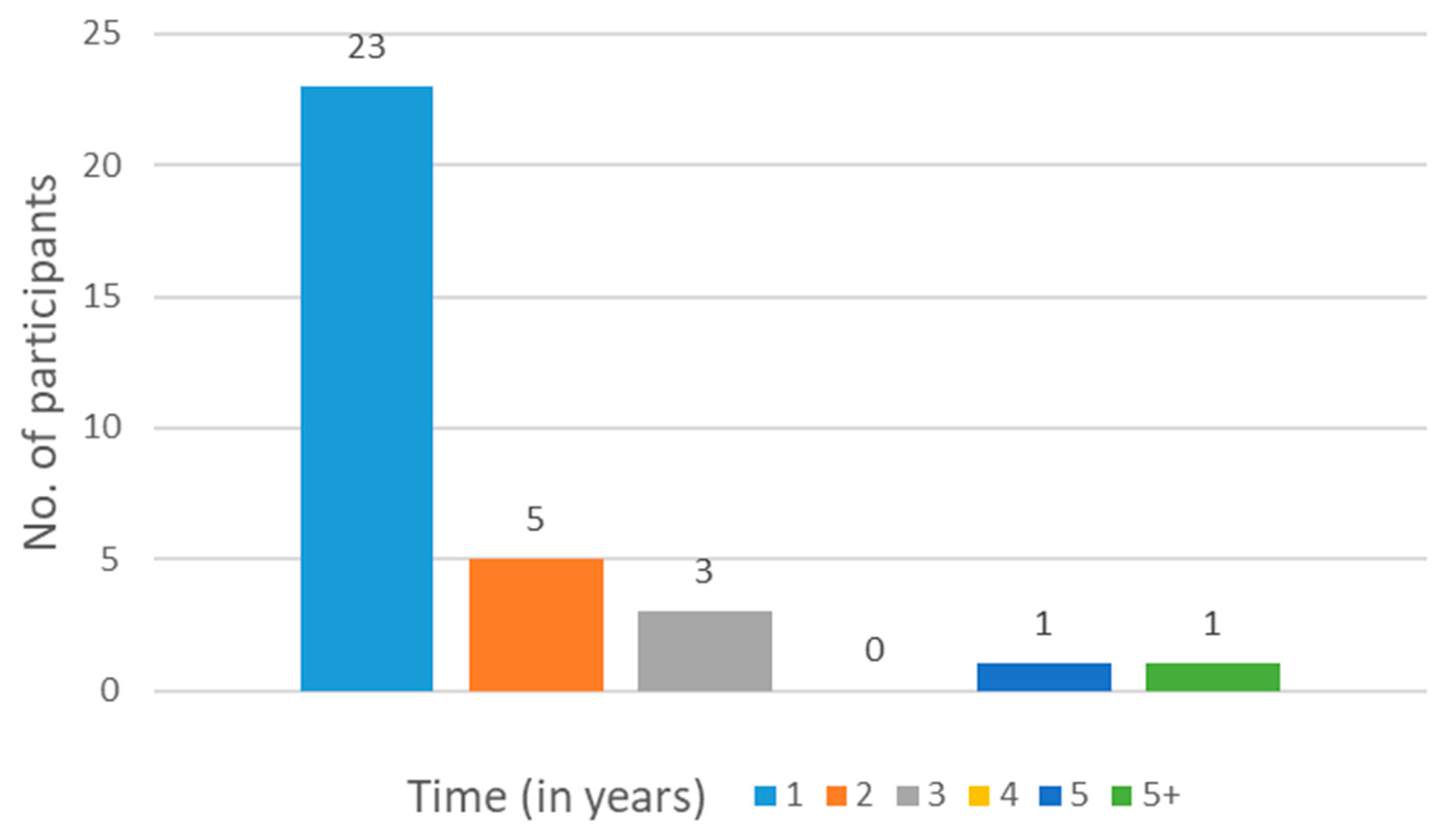

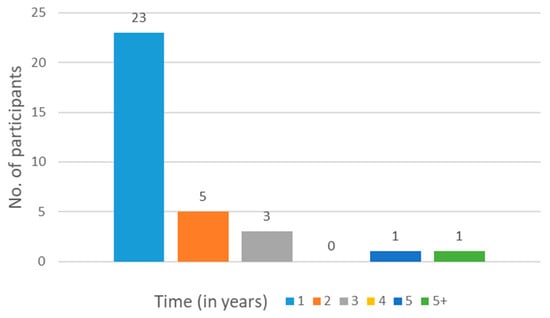

With regards to the length of stay of participants in the UK, there was less diversity. Around 70% of participants (n = 23) had been in the UK for a year or less, while 15% (n = 5) were living in the UK between a 1–2-year timeframe. Complete information on the time spent by participants in the UK is shown in Figure 4. Surprisingly, it was revealed that the listening difficulties encountered by the participants of both maximum and minimum stays may not indicate substantial differences. This observation is consistent with earlier reported works [12,23], which were, respectively, conducted in Australia and New Zealand.

Figure 4.

Time spent by participants in the UK (survey result)—Q9.

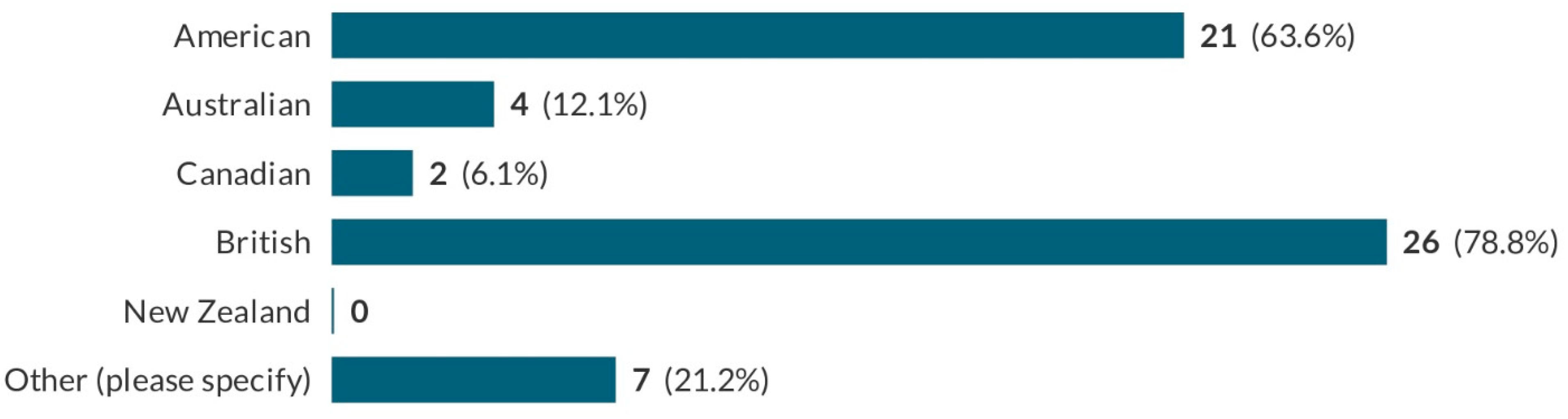

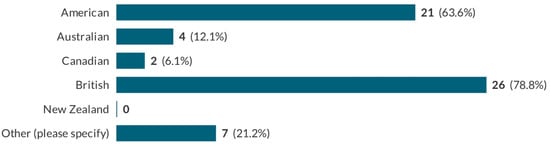

Participants were asked about their previous familiarity with accents to get to know them better. The majority of participants were exposed to British and/or American accents prior to coming to Hull. This could be attributed to the popularity, clarity and understandability of these two widely used accents [24]. Some participants selected Australian and Canadian accents, while a few others chose non-native accents such as Nigerian, Pakistani, Indian, etc. as well. In the survey, many students selected multiple accents with which they were familiar, which is why the percentage exceeds 100%, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Prior accent familiarity (survey result)—Q7.

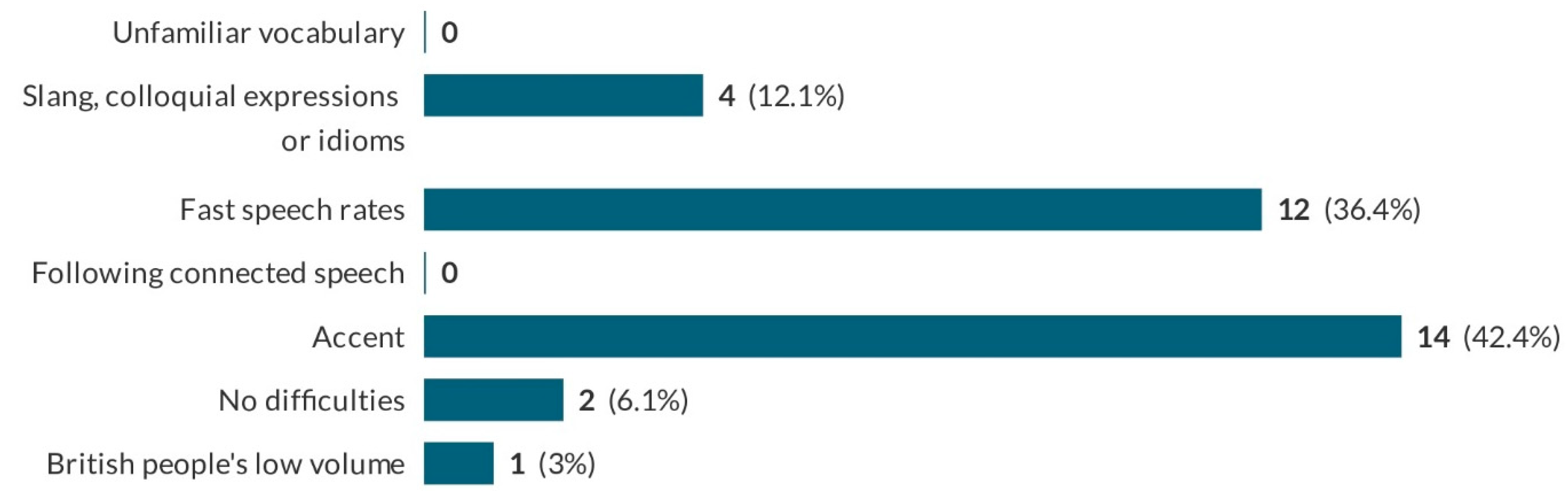

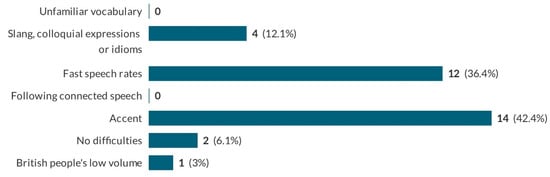

For the sake of fairness and reliability, instead of having a survey question asking directly about accents with a binary answer, the first question (Q1) in the survey listed all the major difficulties associated with understanding native English speech and invited the participants to choose one as per their genuine thoughts and experiences. It is worth mentioning that the purpose of having “unfamiliar vocabulary” and “slang, colloquial expressions and idioms” as separate answer options for Q1 was to get more precise data. The answer “unfamiliar vocabulary” is expected to be more related to the academic use of language while “slang, colloquial expressions and idioms” are more related to everyday language. Two respondents stated that they had no problem with listening comprehension, while around 94% of participants (n = 31) reported they faced difficulties. Figure 6 below sums up the responses given by the participants.

Figure 6.

Biggest difficulty in listening comprehension (survey result)—Q1.

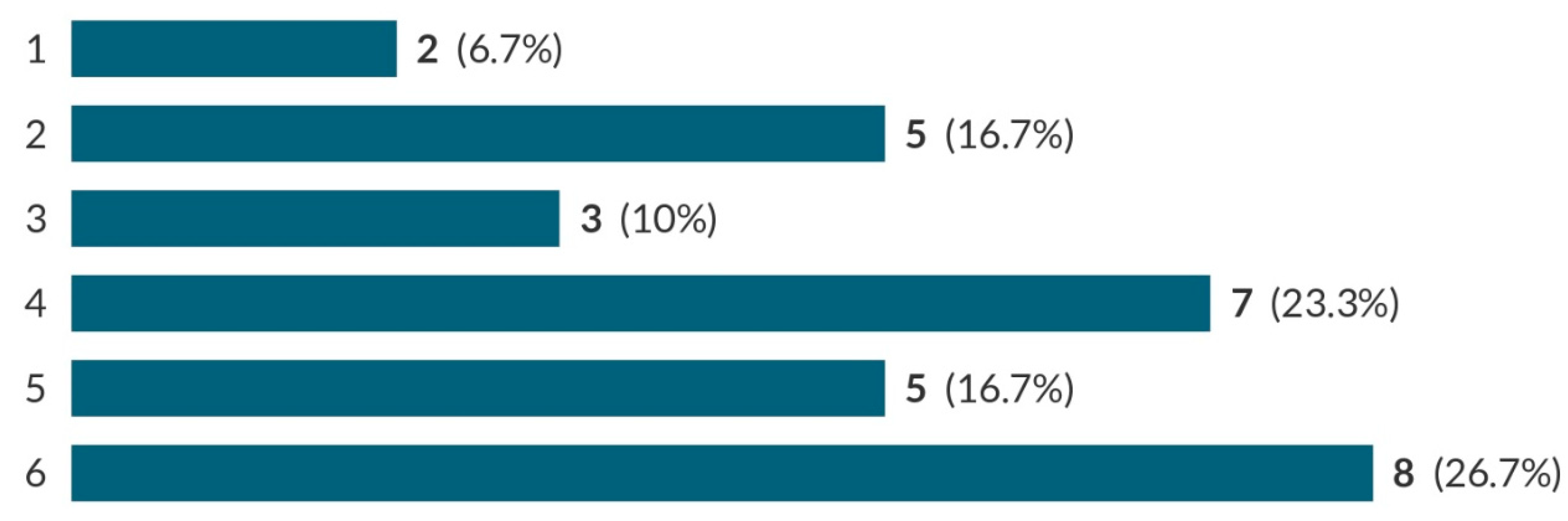

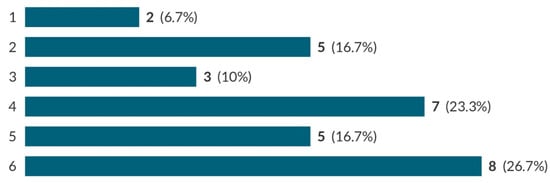

Having established accent as the biggest difficulty in listening comprehension, Figure 7 presents a bar graph to explore the spread of participants’ responses. Out of 30 responses corresponding to accent, 66.7% of them (n = 20) gave an impact score of 4–6 (as illustrated by the bottom three bars in the figure). Thus, the pivotal role of accent in listening comprehension was highlighted.

Figure 7.

Degree of impact of accents on listening comprehension (survey result)—Q2. 1—Lowest impact; 6—Highest impact.

Moving to a more in-depth investigation of accent as one of the biggest barriers to understanding native English speech based on the survey results, this research additionally selected an amount of interview-based data that offer further context and explanations for this answer. As Interviewee 1 (I1) said:

“Frankly speaking, there were a lot of difficulties the first time I arrived, but I could choose only one option in the questionnaire. [It was] the most difficult thing from the list, that’s why accent was number one.”

Within this study, accent has been found to be the biggest factor contributing to listening comprehension difficulties. This result may indicate some confirmation of the findings in previous literature [10,25]. Half of the participants considered that the average speech rate of native speakers is fast, which in turn aggravates their accent-related problems.

- (a)

- Unfamiliarity to variants of British accents:

Commenting further on this language barrier, 33% of participants regarded the great variety of British accents as the cause of listening comprehension difficulties, while the remaining interviewees highlighted their lack of familiarity with local accents. According to their views, the accent they encountered after their arrival in the UK was quite different from the standard British accent they were used to listening to in school or college. A possible explanation for this might be that since Received Pronunciation (RP) and General American (GA) are still the reference accents of English in the ELT world [26], L2 English learners may have very limited exposure to non-standard varieties in the classroom. A small number of those interviewed suggested that their L1 might influence the way English is spoken and taught in their home countries, and even though English is their official or second language, they are exposed to non-native-accented English.

- (b)

- Challenges caused by British English accents:

The qualitative data provides insight into which aspects of a student’s life can be more affected by their listening comprehension difficulties related to British accents. All the students stated that they faced British accent-related challenges in their social life, while 67% (n = 4) mentioned that these challenges had an impact on their academic life as well. Interviewee 5 (I5) commented:

“To be fair, it didn’t have much influence on my academic life because even the lectures and the staff and, you know, just friends, our classmates, they speak English very clearly. However, I would say it’s not the same case in my daily life. An example [of] this [is] when I was working at a tea shop.”

This finding is consistent with that of [12], which pointed out that the distinctive accent of Australian English was a factor contributing to listening difficulties faced by students, particularly when communicating at work and socially interacting with people.

- (c)

- Perception of British accents:

This theme delves into what kind of British accent was perceived by interviewees as the hardest to understand. One half thought that the Hull accent is particularly challenging compared to other cities such as London, Manchester and Reading. Interviewee 2 (I2), for instance, said:

“I’ve been to other cities such as London. It’s easier to understand. I don’t know. I think their accent is different from here. Basically, the London accent and Manchester, too was much clearer there. So those are like the few places where I could understand just from the first statements.”

In relation to another finding, 50% of the interviewees reported facing accent-related challenges when interacting with common people from society. However, they emphasised that the situation was completely different regarding educated British people as their lectures, doctors, administrative staff, etc. Interviewee 4 (I4) shared her thoughts in the following way:

“I realized, like, some people who are educated, they have something like their accent is bit proper rather than those people who are like illiterate or uneducated, people like in shops, like factories, they have a bit more difficult accent.”

Unfortunately, these findings are rather difficult to interpret because there may be a bias towards an accent variety out of the educational level of its speaker. By integrating the responses received using two research tools, it was concluded that findings from the interviews reinforced the survey findings. Accent was stressed as the biggest listening difficulty, followed by fast speech rate.

Though not directly related to the scope of the present work, sociolinguistic aspects are taken into consideration while discussing the communicative challenges faced by international students. Lippi-Green [27] argued that comprehension barriers extend beyond language-related issues to encompass linguistic discrimination. It is worth noting that L1-L2 miscommunication is not mainly due to L2 speakers’ listening comprehension difficulties. A great linguistic variation of the English language should be considered as one of the main reasons for communication problems between L1 and L2 speakers. The varieties of English accents are not reflected in the instruction materials, particularly the ones aimed at developing listening skills. Another reason could be that there is a negative language attitude towards foreign-accented speech; therefore, the responsibility of the communicative act is given to the other group, who speak with an accent [28]. Previous studies such as [27] have reported that the major characters in Disney cartoon movies have Standard English accents, whereas the other characters have distinct accents. This suggests that the characters in question might not be as important as those who have a conventional American or British accent [29]. As a result, disparate accents support a negative attitude towards language.

This is how those in positions of authority maintain the status quo of standard varieties. Individuals are trained that the way they speak is the primary way that their identity is represented. Additionally, people from the lower class, working families and members of specific ethnic communities are disparaged by educational institutions based on their speech patterns. Standard Language Ideology manifests itself through the hierarchy of languages and dialects, the refusal to accept accountability in communication acts by the predominant language group and the propagation of the non-accent illusion. A setting where the standard language mentality is prevalent is in higher education, where faculty members from linguistically diverse backgrounds face stigma because of their identity, accent and language [30].

Furthermore, distinct English dialects are perceived differently. Researchers in England have found that certain dialects are considered vulgar throughout the nation, such as accents from Birmingham or parts of London [27]. Nevertheless, some accents, mainly from the countryside, are said to be charming. Each person has a unique favourite language or dialect sound [31]. There are dialects that are relatively more regarded than others. One area of study has been identifying the source of linguistic attitudes [32]. Language attitudes are shaped by a multitude of circumstances, including social context and personal experience, as he has noted. The literature in this field explains that it is common for people to think that their own speech pattern is the only proper one and that other speech patterns are incorrect [29]. Moreover, several instances of language discrimination in the workplace can be observed while considering the circumstances in the United Kingdom. However, it is reported [28] that people who experience linguistic discrimination at work have had to gradually adapt to the adverse situation.

4.2. Research Question 2 (RQ2)

RQ2 is “What strategies do they often use to mitigate accent-related challenges in their academic and social life?” Having established accent as the biggest difficulty faced by international students in listening comprehension, the next step was to explore how participants cope with barriers due to native-accented English.

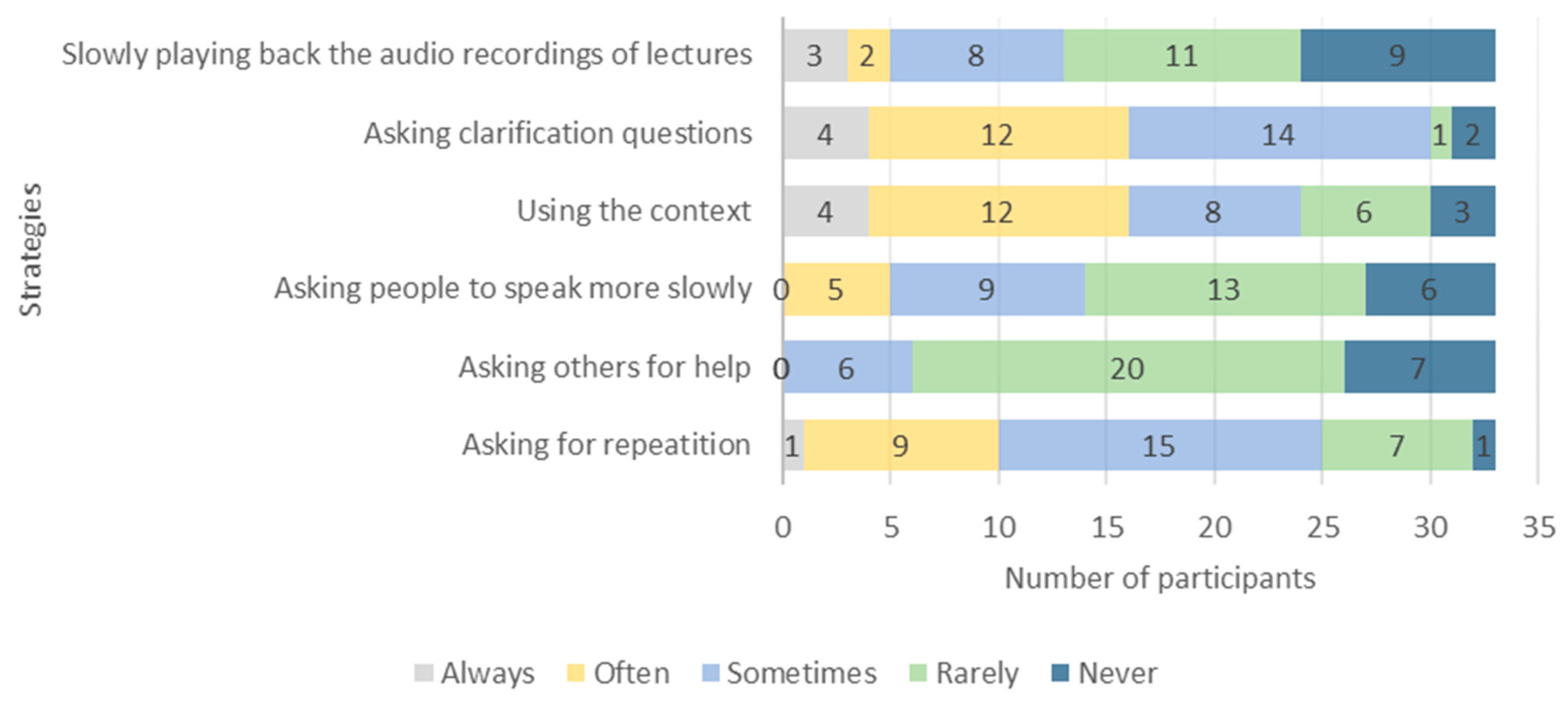

In the survey, the participants were asked in Q3 to share their thoughts on strategies they used to mitigate listening comprehension difficulties on a Likert scale. Q3 is a multi-item scale containing ten statements (a–j), which correspond to 5 strategies (each repeated twice to enhance reliability). However, in Q4, we have 6 strategies. This difference is due to the fact that strategy referring to the speed of talking (in Q3) corresponds to two aspects/statements in Q4: listening to people as well as listening to audio recordings.

The data analysis process here involved coding, simple computation and finally comparing against a criterion. This process was indirectly validated by Q4 (to be mentioned later). Firstly, coding was done to transform the Likert scale (involving subjective strength) to a numerical scale which is more meaningful for further processing, as detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Coding Likert scale options to numbers.

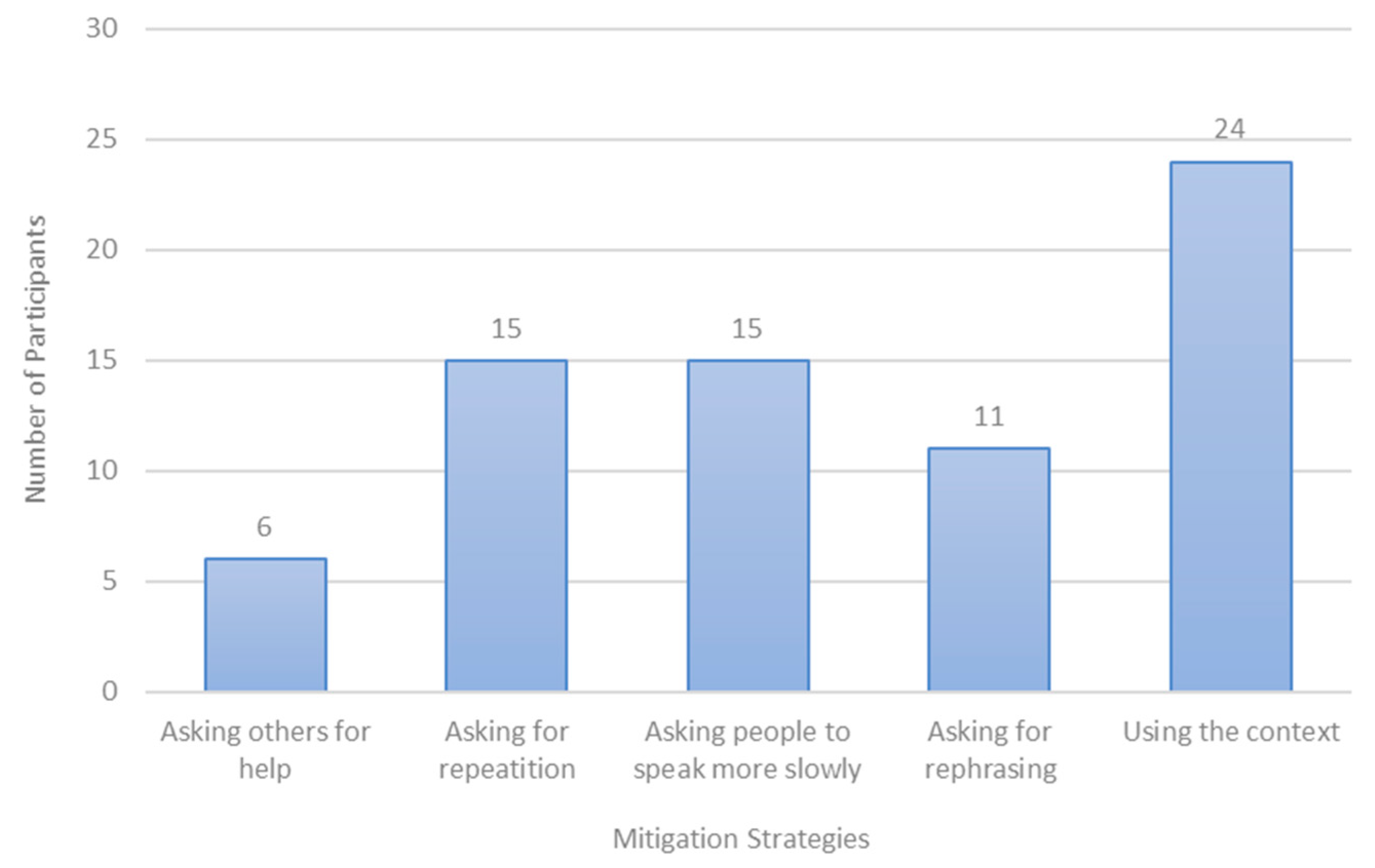

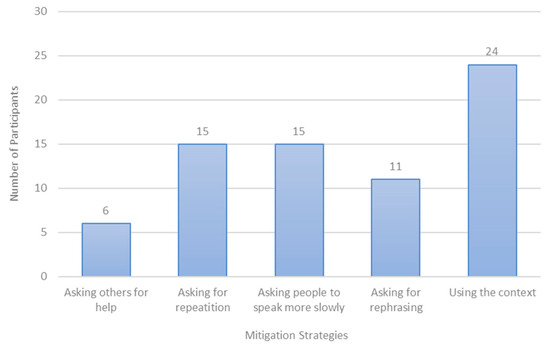

Secondly, for each strategy, the mean rating of the two responses given by each participant was computed as strongly recommended [33]. The final step involved defining a criterion to determine if a participant was using a particular strategy. For data analysis, a participant was considered using a strategy if the mean rating of their responses was positive (greater than 0). Results obtained after data analysis showing the number of participants employing various mitigation strategies are given in Figure 8. Interestingly, it was found that participants had diverse views regarding their preferred mitigation strategies. Many participants were inclined to use multiple mitigation strategies in their academic and social lives while having comprehension difficulties, which is why the total number of participants in Figure 8 is more than 32.

Figure 8.

Mitigation strategies (survey result)—Q3.

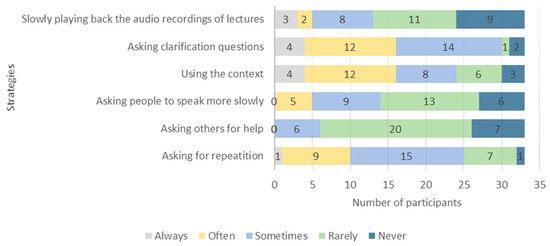

A stacked bar graph showing the frequency of using various mitigation strategies by international students is illustrated in Figure 9. As exhibited in the graph, most of the participants often or sometimes used a particular mitigation strategy. This confirms the estimation approach used in the analysis of Q3 (Figure 8). For example, in Figure 8, 24 participants favoured using contextual understanding. This is consistent with Figure 9, where 4, 12 and 8 participants (24 in total) respectively reported that they always, often and sometimes used context to understand British people’s speech.

Figure 9.

Frequency of using mitigation strategies (survey result with n = 33)—Q4.

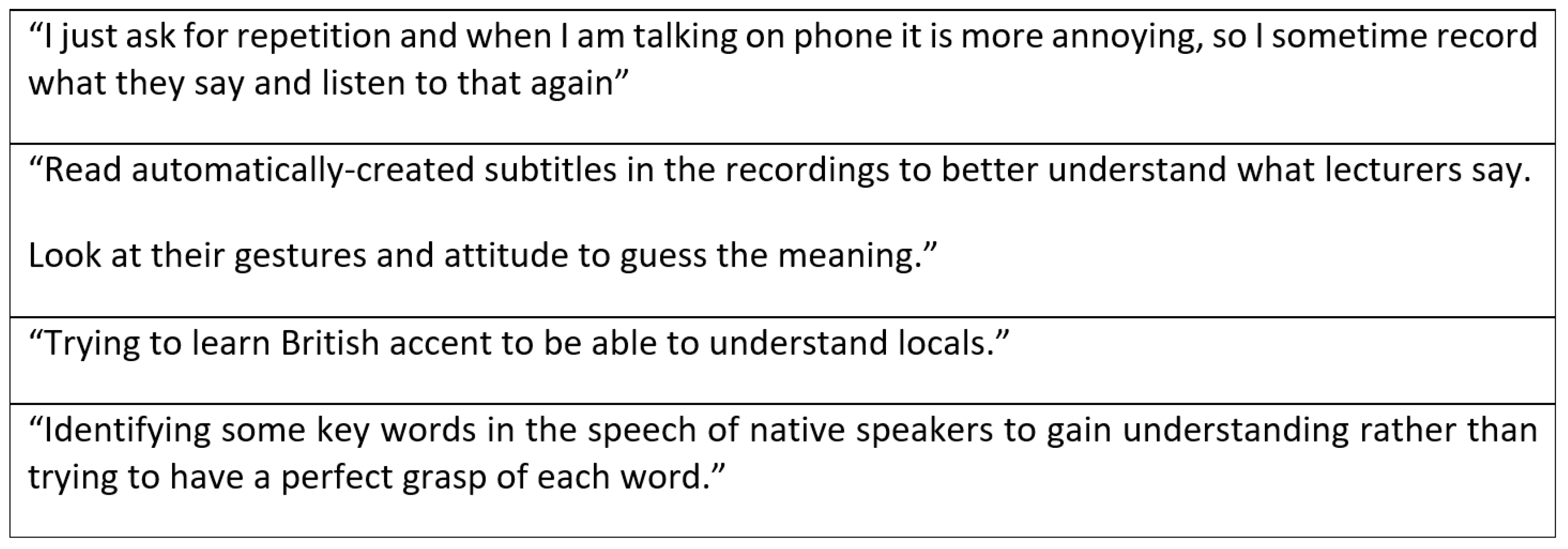

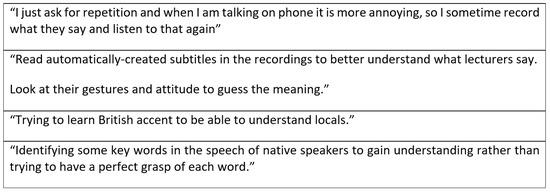

For the sake of rigorous analysis and given the breadth of mitigation strategies, an open question was presented to the participants: “If you used any other strategy not listed above, please specify here”. Figure 10 presents the valuable comments received corresponding to this open question.

Figure 10.

Misc. strategies used to improve understanding British people’s speech (survey result)—Q4a.

Following the identification of accent as the biggest obstacle to listening comprehension, the next step is to examine the strategies used among students to cope with these challenges through interviews.

- (a)

- Strategies employed by international students:

The interview data also largely provided the answer to the second research question. When the participants were asked how they managed to understand native-accented speech, a common strategy among all of them was asking for repetition. As two participants stated:

“I say ‘pardon’ so that they repeat themselves.”(I5)

“If I don’t get it clearly, I just ask them to repeat themselves.”(I2)

These results reflect that asking for repetition and clarification were among the most common communicative strategies used by EFL learners to resolve communication breakdowns. Other strategies employed by the interviewees were paraphrasing the information they received, asking their interlocutors to paraphrase what was said, asking friends for help by translating into their mother tongue and listening to the recordings of the lectures with or without subtitles. Moreover, one participant said becoming more aware of how words were pronounced with the local accent helped her to gain better listening comprehension. Finally, another subject commented that she recorded sensitive telephonic conversations such as medical consultations and job interviews so that she could listen to the audio later to be able to grasp the details.

- (b)

- Opposing attitudes towards the most used strategies:

Two divergent and often conflicting discourses emerged. On one side, one-third of the participants did not mind asking people to repeat themselves since they believe, in general, local native speakers are friendly. Thus, these interviewees did not feel anxious when doing so, even for a second time. Nonetheless, one participant reported feeling embarrassed if she did not catch the meaning of the oral message after it was being repeated once. Therefore, she avoided asking for a repetition for a second time. L2 students [12] also used this strategy of asking for a repetition; however, they were not willing to do so many times in contrast to interviewees of the present research.

According to research [12], if miscommunication was not resolved, L2 students considered asking for repetition again may create an embarrassing moment for both interlocutors. Therefore, they developed another strategy: pretending to understand. However, only one interviewee of the present research reported pretending to understand what was being said to avoid feeling judged and ashamed.

- (c)

- Impact of accents on students’ learning experiences and social interactions:

The investigation of the strategies employed to address accent-related issues shed light on new themes. For example, the impact of these difficulties on students’ learning experiences and social interaction emerged. This impact can be classified as positive and negative effects related to their experiences both on- and off-campus. The corresponding findings can be presented and examined as follows:

Positive effect on learning experiences.

A participant considered that all the lecturers who taught her had a clear accent. She commented:

“All lecturers who taught me this course have beautiful English, understandable English, and for me it was a pleasure to listen to their lectures, because I enjoyed the sound of the language itself.”(I1)

- i.

- Negative effect on learning experiences.

A student who had trouble understanding the lectures in the initial stage of her studies thought this had impacted her academic performance significantly. Another student said that although listening to the recordings of the lectures was helpful, it was time-consuming, too.

In summary, limited understanding of lecture content in the initial months of their sojourn was not seen as a serious issue compared with the communication breakdowns in their social life. With regards to the impact of accented speech on students’ social life, of interest here is the attitude these difficulties awoke in participants. It is worth noting that these listening comprehension challenges produced antagonistic attitudes.

- ii.

- Positive effect on social life.

Lack of understanding of spoken English due to accents inspired one participant to learn the Hull accent. Her motivation was being understood faster and better by the customers she interacted with. Even though another interviewee had a difficult time understanding the Hull accent during the initial weeks after her arrival, she spent a lot of time interacting with local people before the start of the academic year. Consequently, she became self-confident in asking for repetition, paraphrasing or telling her British interlocutors that she could not understand “the English” they were speaking. Additionally, she learned more about their customs and traditions and became more familiar with their accent within 2 months of her arrival in the UK.

- iii.

- Negative effect on social life.

One interviewee showed no interest in taking action regarding this language barrier. In fact, he emphasised that he knew about the accent diversity of the UK even before coming here to study. Two other interviewees felt guilty for not being able to understand native English speakers. As a matter of fact, they shared specific incidents where they were very ashamed because they could not understand what they were told. One of them shared a negative experience, as follows:

“I used to work as a security guard during my Masters. We usually talk on radios when we need to communicate with different guards. So, there were different people. All were British, but they were from different places, so all they had different accents. So, I always had trouble, and sometimes those people had to come to my place, to my position to tell me that “we are saying this to you”, “Why don’t you understand”? That was so embarrassing for me.”(I4)

In a similar vein, I6 said:

“And when people ask me, what do you study in the university? I say TESOL. So, I am so embarrassed to say that because sometimes, I don’t understand what they say. And I say, they will judge me. And they tell me, she’s studying teaching English, but she doesn’t understand what we tell her.”

Building cross-cultural relationships is an important factor for successful academic and social adjustment. Although interviewees did not experience any linguistic prejudice or language discrimination, difficulties in understanding British accents themselves could be regarded as a barrier to socialising with native speakers.

Based on the two sources of results, a small variation in the trend of mitigation strategies to better understand native English speech has been observed. Results from the survey showed ‘contextual understanding’ as the most widely used strategy followed by ‘asking for repetition’. However, the interviewees revealed ‘asking for a repetition’ as their first preference. Findings from both quantitative and qualitative data analysis opened a new dimension to accent discussion, which is related to the perception of mitigation strategies.

4.3. Research Question 3 (RQ3)

RQ3 is “What is their perception towards the effectiveness of these strategies based on their experience?”. This research question is answered by analysing data from question 12 and question 15 of the interview. The interview answers provide a comprehensive picture of the students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of their strategies. Even though participants highlighted the challenges in their academic life brought by native-accented speech, the vast majority agreed that the strategies used were helpful enough to handle linguistic issues. On the other hand, concerns regarding the limitations of their strategies to deal with communication breakdowns outside campus were more widespread.

Perception of the effectiveness of their strategies in academic life:

As mentioned in the discussion on RQ1, not all participants faced accent-related difficulties in the academic environment. A common view among interviewees who found difficulties in understanding British spoken English in educational settings was that those types of difficulties could be more easily resolved than the ones faced in their social lives. The first finding may be explained by the fact that participants could access recordings of the lectures and play them as many times as necessary. As a matter of fact, Interviewee 6 said that she occasionally used the subtitles for extra help. She claimed:

“Listening to the recordings of lectures with subtitles was enough for me.”

Another reason could be that they could compensate the listening difficulties encountered in their classes with further reading about the subject topics for a better and deeper understanding. As one participant mentioned:

“So, that was all (about challenges related to academic life) I think because mostly what I also do is self-study and read books, I think the problem was that the lecturer (a native speaker) spoke fast and because of his accent, too.”(I3)

Perception of the effectiveness of their strategies in social life:

Students reported major and more frequent listening difficulties in social settings. All students who were interviewed showed their concern about this matter. For instance, some interviewees pointed out that the most difficult accents they heard were from ordinary people such as taxi drivers, shop assistants, bus drivers, etc. To the question: “Were the strategies you used in your academic life to manage the difficulties due to unfamiliar accents equally useful in your social life”, I4 replied:

“No, it was not. No, it was not helpful. But I feel like I got the experience over to try to tackle this language barrier or accent.”

These results reflect other research [12], which also found that, apparently, international students had more trouble understanding spoken English in social contexts than in academic settings.

4.4. Research Question 4 (RQ4)

RQ4 is “What recommendations can they give to incoming and future students to prepare for this situation?”. A common view among interviewees was that L2 English learners who are potential international students need to be exposed to British accents before coming and while staying in the host country. Opinions of most participants coincided regarding the great availability of resources to build listening comprehension skills in this digital age. For instance, I1 commented:

“Nowadays there are a lot of sources where you can hear real English, videos, films, series, YouTube videos. Different bloggers who you can listen to all the time and in order not to have problems with listening. We need to listen to different accents. Not only BBC English, as I said, not only English which is used in London or somewhere at higher institutions, but also the one spoken by ordinary people, like workers, builders, shop assistants. The more you listen, the more you understand.”

Other response to this question was:

“One of the things that I regret is that I didn’t expose myself to the British environment as much as possible. I was kind of worried about being judged and I preferred to stay home than interacting with people. If it was about maybe one year ago, when I arrived here, I definitely would look for a job. I would volunteer in a store to interact with British people, because then staying home and waiting for our English knowledge to be increased nothing will happen, we need to be exposed to the people, to the environment and we cannot predict the accent of each people. So, we have to be prepared for that.”(I6)

This finding on the importance of exposure to a specific accent to increase familiarity and comprehension is aligned with the results reported in another research [34]. This exposure to an authentic English-speaking environment could equip students with not only linguistic but also cultural competence. Eventually, this cultural knowledge could further improve their listening comprehension skills.

4.5. Limitations of This Study

Despite having successfully achieved its primary objectives, it is acknowledged that this study suffers from some limitations, as detailed below:

- One limitation is its small sample size. The study involved 33 participants (from 9 different nationalities) in the survey and 6 of them participated in the interview and thus may not be very representative of the large population of international students. Nevertheless, the objective of this research study was to draw an insight into the subject matter using a realistically available dataset.

- The present study considered ‘accent’ as a whole and did not go into the various components and lower-level features of accents.

- The present study is primarily based on the opinions and experiences of international students. The reliability of the results can be further improved by designing and giving listening tests to the participants. Data obtained from tests can be correlated with data acquired from research tools. Alternately, prior to interviews, participants can also be requested to hear, compare and identify regional British accents, including that of East Yorkshire.

- Question 2 of the questionnaire (Appendix A) investigated various factors that could affect understanding of British spoken English. Item (d) specified ‘Speed of listening’ as one of the factors. It would have been more precise and clearer to use ‘Speed of talking’ instead.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

There is an increasing trend in research on the globalisation of universities. This stresses the immense need to thoroughly address challenges faced by international students, which could enhance their experience in foreign countries. This study aimed to investigate one major aspect of English language listening which is related to unfamiliar British accents and how they can negatively impact students’ listening comprehension while living and studying abroad. Furthermore, it examined what international students consider has helped them have a better overall experience. Ultimately, the objective of this study is to provide some support to overseas students to mitigate this adaptation issue. To achieve these objectives, an online survey and semi-structured interviews were conducted following a mixed methods research approach with international students as participants whose mother tongue(s) is not English and who attend or (recently) attended the British university being examined in this research paper.

The survey involved data collected from 33 participants recruited from diverse nationalities, levels and programmes of study. The statistical analysis of the data from the survey revealed that accent is the biggest factor contributing to listening comprehension difficulties faced by international students. Six participants were interviewed using purposive sampling. Participants generally talked positively about the support available to them, e.g., recording of lectures, language-related workshops and activities. However, it was found that not all international students are aware of language support services available to them on campus and in the local community.

This study may help in supporting the design, development and use of listening materials in future ELT, especially in terms of offering students valuable exposure to diverse accents. Raising awareness of the variations in pronunciation of native English speakers and greater exposure to various accents can improve the ability and confidence of L2 English users in terms of listening comprehension. Using authentic listening materials such as recordings, songs and videos could help students to reduce accent-related listening comprehension difficulties. Language instructors can demonstrate to students by pronouncing the same words with different accents and having them repeat these words so that learners can notice the basic features of different accents. Finally, the curriculum of English in colleges, preparatory and in-sessional courses could be adjusted to reduce the impact of listening difficulties.

Furthermore, language support services for international students could be further improved by initiating services such as peer tutoring, peer-pairing programmes and customised academic workshops run by local English teachers. They could work as a team to develop open online courses to provide international students with the listening skills needed to achieve their academic and social goals. The academic and cultural content of these courses should be designed keeping in mind the students’ field of study and the accent of their host city, respectively.

Finally, one way for HEIs to challenge the standard language mentality and the monolingual worldview that many of their students firmly adhere to is by making sociolinguistic classes required. Another way could be by bringing up sociolinguistic topics in English class discussions. In addition, classroom pedagogies, workshops and cross-cultural training should be used to foster students’ openness to accent diversity. A statement addressing accent variations should be included in course policies to make communication efforts obvious. It is important to use pedagogical activities that encourage students to view accents as a natural element of language rather than something that must be fixed. Workshops that provide orientation and guidance on how to behave and what to anticipate in the event of accent discrimination may also be beneficial for educators who are foreign-accented speakers. In order to build diversity-oriented environments, it is imperative that we increase awareness of the linguistic reality of the English language.

It is expected that wider dissemination of these findings will help improve the linguistic experience of international students in English-speaking countries. Although the present study has been conducted at a British university, the researcher believes that the findings from this research are relevant and applicable to other English-speaking environments having similar dynamics with minor changes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.I.; methodology, K.R.V.D.; validation, K.R.V.D.; formal analysis, K.R.V.D.; investigation, K.R.V.D.; writing—original draft preparation, K.R.V.D.; writing—review and editing, J.I.; guidance on data analysis and visualization, J.I.; funding for Article Processing Charges, J.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the institutional ethical guidelines as approved by the Faculty of Arts, Education and Culture (FACE) ethics committee at a British university.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data is available in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Ian Hutchinson, Lecturer in TESOL for supervising this research. We respect his choice of not being mentioned as a co-author though we greatly appreciate his significant contribution. Moreover, we would like to acknowledge all the participants who voluntarily took part in the research by sharing their valuable experiences and insights.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire

Appendix B. Interview Questions

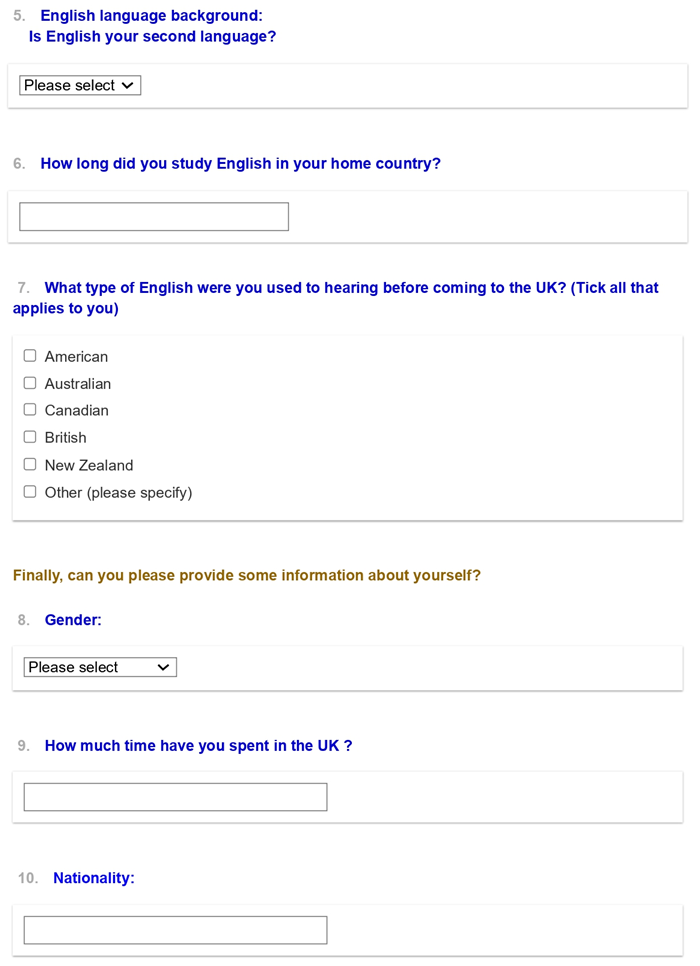

The interview will address RQ1 to RQ4, as shown in Table A1.

Table A1.

Interview questions.

Table A1.

Interview questions.

| Question No. | Remark/ Research Question | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Trust and Ethics | Hello, my name is Katherine Vasquez. I am a master’s student in English Language Teaching at the University of Hull. |

| Q2 | How are you doing today?

| |

| Q3 | Thanks for your willingness to take part in this interview. This research is about challenges faced by international students to understand British accents. I am interested in knowing your thoughts and opinions, which do matter a lot! | |

| Q4 | You have the right to withdraw any time without having to give any reason. Just to remind you that all information will remain strictly confidential and codes will be used to maintain your anonymity. | |

| Q5 | I will be audio-recording the interview subject to your consent. The interview consists of three opening questions and eight specific questions and will last around 35-40 minutes. I will be happy to prompt you throughout the interview in case something is not clear. Please note that there are no right or wrong answers to any of the questions. Once the interview starts, please feel free to talk about your experiences over the initial phase of your stay in the UK Do you have any questions about the project? Would you like to start now? | |

| Q6 | Opening Questions | Have you lived or studied in any English-speaking country before you came to Hull for your studies? |

| Q7 | Are you a full-time student? | |

| Q8 | Are you based in Hull or do you commute from some other city to Hull? | |

| Q9 | RQ1 | Among various difficulties mentioned in the questionnaire, you chose accents as the biggest difficulty you had in understanding native English speakers. Can you elaborate more on that? |

| Q10 | RQ1 | Can you give me concrete examples when you experienced problems due to unfamiliar accents inside the university? (Additional prompts: While listening to lectures, conversation with British class fellows, talking to Student union or any other office etc.) |

| Q11 | RQ2 | How did you manage those situations? (Additional prompts: Did you request for repetition? Did you ask speaker to slow down? Or did you request speaker to say it again in different words? etc. |

| Q12 | RQ3 | To what extent do you think, your strategies were helpful in overcoming challenges due to unfamiliar accents? |

| Q13 | RQ1 | Do you feel that you experienced the same kind of difficulties in understanding English accents outside and inside the university? |

| Q14 | RQ1 | Can you give me concrete examples when you experienced problems due to unfamiliar accents outside the university? (Additional prompts: While listening to shopkeepers, conversation with landlord, talking to someone on phone etc.) |

| Q15 | RQ2, RQ3 | Did the strategies you use in your academic life to manage the difficulties due to unfamiliar accents, were equally useful in your social life? |

| Q16 | RQ4 | Now that you have several opportunities to interact with British people, what advice you can give to students in your home country who plan to study in the UK in terms of a better listening comprehension. |

| Q17 | Final Questions | Is there anything else you would like to share or add to our discussion? |

| Q18 | Thank you very much for your time and generous participation in this study. Good luck with your studies! |

Key: Green = [___5___] Yellow = [____8_____] Blue = [___2____] White (Opening Qs) = [___3____].

References

- Michał, W.; Ilan, A. Language and communication in international students’ adaptation: A bibliometric and content analysis review. High. Educ. 2023, 85, 1235–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Suryanto, S.; Betha, L.A.; Noor, A.O. Learning English through international student exchange programs: English education department students’ voices. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. Learn. 2022, 7, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Yough, M.; Wang, C. International students in higher education: Promoting their willingness to communicate in classrooms. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2018, 10, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, P.W. Student Migration to the UK. Migration Observatory Briefing, 5th ed.; COMPAS, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Study in the UK. International Student Statistics in UK. 2023. Available online: https://www.studying-in-uk.org/international-student-statistics-in-uk/ (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Zhou, Y.; Todman, J. Patterns of adaptation of Chinese postgraduate students in the United Kingdom. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2009, 13, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, D.J. Learning to Listen; Dominie Press: Lebanon, IN, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Phomprasert, J.; Grace, M. The Effects of Accent on English Listening Comprehension in Freshman Students Studying Business English at Phetchabun Rajabhat University. Int. J. Learn. Teach. 2020, 6, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownell, J. Listening: Attitudes, Principles, and Skills, 5th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.-S.; Wu, B.W.-P.; Pang, J.C.-L. Second language listening difficulties perceived by low-level learners. Percept. Mot. Ski. Learn. Mem. 2013, 116, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busher, H.; Lewis, G.; Comber, C. Living and learning as an international postgraduate student at a Midlands university. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2016, 40, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E. Social and Educational Challenges of International Students Caused by Accented English in the Australian Context: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of Linguistic Experience. Master’s Thesis, Griffith University, Nathan, QLD, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hope, K. Investigating the Impact of Liverpool Accent on Language Learners’ Experiences in a Study Abroad Context. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Koyuncu, S.; Kumpulainen, K.; Kuusisto, A. Teaching English as a second language in the early years: Teachers’ perspectives and practices in Finland. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. Problems Chinese International Students Face during Academic Adaptation in English-Speaking Higher Institutions. Master’s Thesis, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bauerschmidt, A.T. International Students’ Challenges at an English-Language University in Montréal. Master’s Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, N. Enhancing international students’ experiences: An imperative agenda for universities in the UK. J. Res. Int. Educ. 2011, 10, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pho, H. ‘Am I gonna understand anybody?!’: International students and their struggles to understand different ‘Englishes’ in an international environment. The Language Scholar, 7 September 2020; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, I.-C. Addressing the issue of Teaching English as a Lingua Franca. ELT J. 2006, 60, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohrabi, M. Mixed method research: Instruments, validity, reliability and reporting findings. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2013, 3, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, D. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, C. How much do learners know about the factors that influence their listening comprehension? Hong Kong J. Appl. Linguist. 1999, 4, 17–42. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.; Li, M. Asian students’ voices: An empirical study of Asian students’ learning experiences at a New Zealand university. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2008, 12, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrine, N. Investigating the Effect of English Accents on Student’s Listening Comprehension—The Case of First-Year Students. Master’s Thesis, University Mohamed Khider Biskra, Biskra, Algeria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, A.; Trudgill, P.; Watt, D. English Accents and Dialects; Hodder Education: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, A. Re-conceptualizing speaking, listening and pronunciation: Glocalizing, TESOL in the contexts of World Englishes and English as a Lingua Franca. TESOL Q. 2019, 53, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippi-Green, R. English with an Accent: Language, Ideology and Discrimination in the United States; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Papuc, R.D. Language variation, language attitudes and linguistic discrimination. Essex Stud. J. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herk, G. What Is Sociolinguistics? John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Özer, H.Z. “You’ve Gotta Change Your Accent”: An Online Discourse Community’s Language Ideologies on Accentedness in Higher Education. Novitas-ROYAL (Res. Youth Lang.) 2022, 16, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, L.; Trudgill, P. Language Myths; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, P. Attitudes to Language; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M.A. Using multi-item psychometric scales for research and practice in human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, R.C.; Fitzmaurice, S.M.; Bunta, F.; Balasubramanian, C. Testing the effects of regional, ethnic, and international dialects of English on listening comprehension. Lang. Learn. 2005, 55, 37–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).