Identity Development of Career-Change Secondary Teachers: A Systematic Review of Theoretical Lenses, Emerging Identities, and Implications for Supporting Transition into Teaching

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“becoming a professional cannot be reduced to acquiring a number of abilities and skills … Rather, teaching is conceived ‘as a composite of technique, analysis, interpretation and judgment’ (Forzani, 2014, p. 365) … In this sense, becoming a professional teacher means developing a professional way of seeing, valuing, and judging teaching and learning situations and thus becomes a matter of developing a professional identity as a teacher” (p. 508).

- (1)

- What theoretical frameworks are used in the literature to explore SCCTs’/CCTs’ teacher identity development?

- (2)

- What emerging teacher identities do CCSTs/CCTs take on, and what do they need to experience successful teacher identity development?

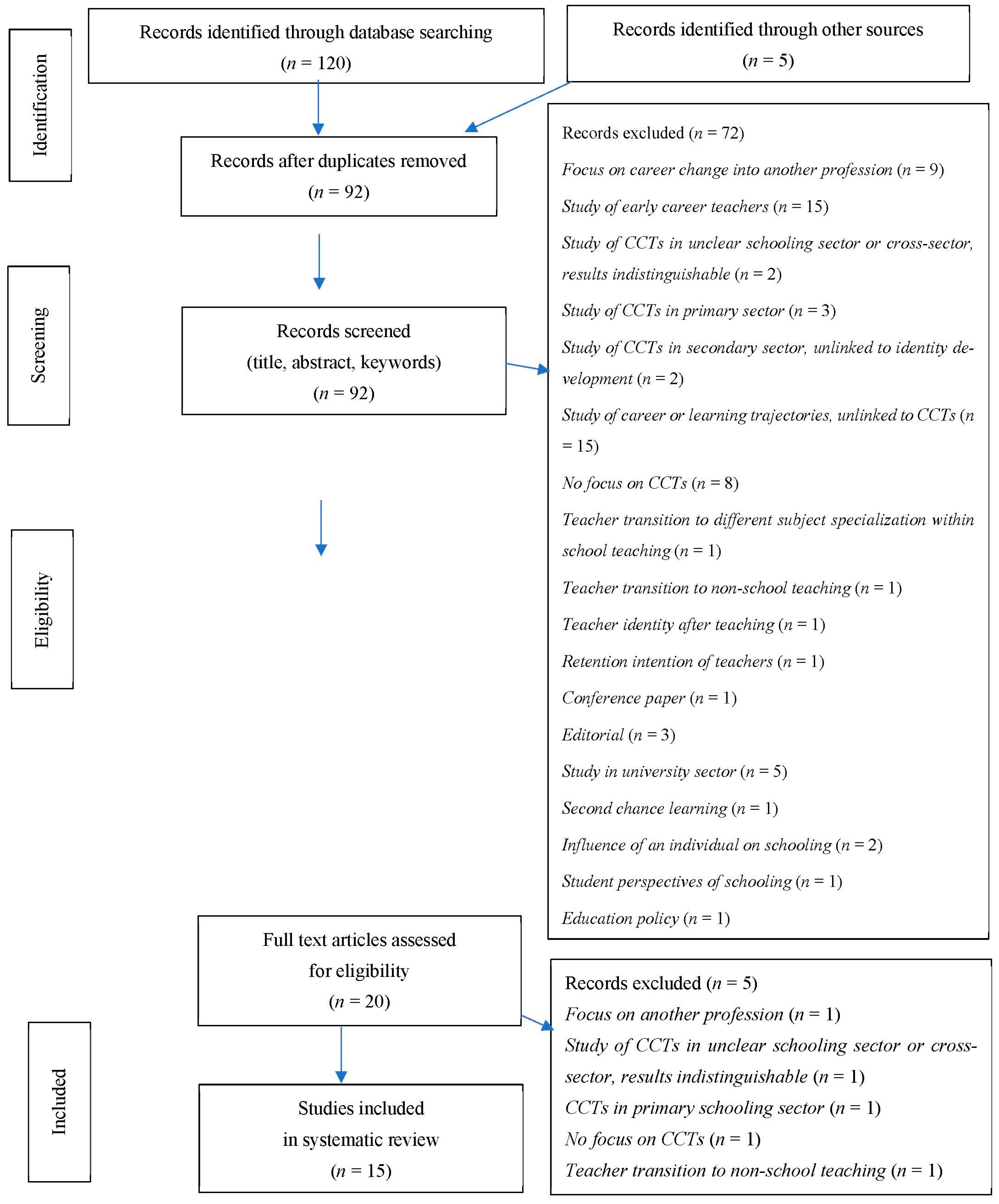

2. Methodology

- EITHER (teacher identity OR professional identity)

- AND EITHER (Second-career OR Second career OR Career-changers OR Career changers)

- AND EITHER (Teacher OR Teach* OR Educator*).

| Inclusion | Exclusion | Examples of Excluded Text | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | CCSTs in ITE and/or CCTs in teaching positions, including VET teachers in schools, who have come from non-school teaching careers | Focus on participants in a second career in any other profession; focus on teachers in general, early career teachers, or both first-career teachers (FCTs) and CCTs. Focus on VET trainers. Teachers who change sectors and/or subjects. | Li and Lai [36]. Excluded because participants’ career transition was within (not into) high school teaching. Seyri and Mostafa [37]. Excluded because the focus was on the identity development of early career teachers. |

| Research focus | Abstract includes keyword: identity | Abstract does not include keyword: identity | van Hiejst, Cornelissen, and Volman [38]. Excluded because the keyword (identity) is missing from the abstract. |

| Theoretical framework | Theoretical framework potentially relates to identity development for CCTs/SCCTs, e.g., career transition or development; adult transition; identity development; and self-determination theory | Theoretical framework unspecified, or potentially related to teacher beliefs, motivation, expertise, and expectancy theory | - |

| Focus on CCSTs’/CCTs’ perceptions and/or experiences of their teacher identity development | Investigation of factors related to CCTs/SCCTs’ own perceptions and/or experiences of their teacher identity development | Investigation of factors unrelated to CCTs/SCCTs’ own perceptions and/or experiences | Wilkins and Comber [39]. Excluded because of lack of focus on CCTs’ identity development. |

| Schooling sector | Middle school, high school | Kindergarten, elementary school, tertiary sector, vocational teaching outside the school sector | Nielsen [40]. Excluded because CCTs were from all schooling sectors and results were inseparable. Živković, P. [41]. Excluded because participants were CCTs in primary schools. |

| Curriculum subject and school setting | Any, within the schooling environment | Subject being taught privately, or in an environment other than a school | Colliander [42]. Excluded because participants moved into adult education. Taylor and Hallam [43]. Excluded because participants taught outside school settings. |

| Empirical research | Papers that report original empirical research | Theoretical papers, opinion pieces, literature reviews | - |

| Quality assurance processes | Papers published in peer-reviewed journals | Book chapters, conference papers, dissertations | Dos Santos et al. [44]. Excluded because it is a conference presentation. |

| Accessibility for authors | Published in English, full text available online | Published in any language other than English; full text unavailable online | - |

3. Findings

3.1. What Theoretical Frameworks Are Used in the Literature to Explore Career-Change Teachers’ Identity Development?

3.1.1. Wenger’s Theoretical Frameworks Most Widely Applied

3.1.2. Applications of Multiple Theoretical Frameworks

3.1.3. Theoretical Perspectives Related to Teacher Identity as Doing or Being

3.1.4. Theoretical Perspectives about the Influence and Malleability of Prior Beliefs

3.1.5. Theoretical Perspectives Related to the Influence of Others

3.1.6. Application of Career Development Theories

3.2. What Emerging Teacher Identities Do CCSTs/CCTs Take on, and What Do They Need to Experience Successful Teacher Identity Development?

3.2.1. Continuity with Previous Career (Seeking Confidence)

3.2.2. Self-Efficacy Enhanced (Seeking Recognition)

“I definitely want to use these skills in my teaching. but in this school, skills and knowledge like these are seen as not very relevant to a school context, like what happens within these school walls is so different from what happens outside and the only way you can get the knowledge you need is by doing teaching, nothing else counts! For me that’s a really strange view and it really limits me as a teacher and undermines what I can offer that is different from regular teachers” (p. 940) [15].

3.2.3. Creating “Out-of-the-Box” Identities (Seeking Instructional Leadership)

3.2.4. CCTs’ Views about ITE

4. Discussion

4.1. Special Characteristics of CCTs

4.2. Implications for ITE

4.3. Implications for CCTs’ In-School Experiences

4.4. Theoretical Frameworks for Research in the Field

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Education Counts. Initial Teacher Education Statistics. Available online: https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/initial-teacher-education-statistics (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschappen. Rapportage Zij-Instroom Leraren 2020; Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschappen: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marinell, W.H.; Johnston, S.M. Midcareer entrants to teaching: Who they are and how they may, or may not, change teaching. Educ. Policy 2014, 28, 743–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadharajan, M.; Buchanan, J. Career Change Teachers: Bringing Work and Life Experience to the Classroom; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C.; Thomas, S.; Sim, C. Mature age professionals: Factors influencing their decision to make a career change into teaching. Issues Educ. Res. 2017, 27, 185–197. [Google Scholar]

- Dadvand, B.; van Driel, J.; Speldewinde, C.; Dawborn-Gundlach, M. Career-change teachers in hard-to-staff schools: Should I stay or leave? Aust. Educ. Res. 2023, 51, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogg, L.; Elvira, Q.; Yates, A. What can teacher educators learn from career-change teachers’ perceptions and experiences: A systematic literature review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 132, 104208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruitenberg, S.K.; Tigchelaar, A.E. Longing for recognition: A literature review of second-career teachers’ induction experiences in secondary education. Educ. Res. Rev. 2021, 33, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. Constructing a new professional identity: Career change into teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, C. ‘Elite’ career-changers and their experience of initial teacher education. J. Educ. Teach. 2017, 43, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, L.C.; Ladd, H.F. The hidden costs of teacher turnover. AERA Open 2020, 6, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.L.; Goodman, J.; Schlossberg, N.K. Counselling Adults in Transition: Linking Schlossberg’s Theory with Practice in a Diverse World, 4th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, S.E.; Arthur, M.B. The evolution of the boundaryless career concept. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 69, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.; Oliveira, A.W.; Paska, L.M. STEM career changers’ transformation into science teachers. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2013, 24, 617–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, J. “It’s like starting all over again”: The struggles of second-career teachers to construct professional identities in Hong Kong schools. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2018, 24, 931–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, K.; Warhurst, R. Career transition as identity learning: An autoethnographic understanding of human resource development. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2019, 22, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, G.; van der Heijden, B.I. Career identity and its impact upon self-perceived employability among Chilean male middle-aged managers. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2012, 15, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grier, J.M.; Johnston, C.C. STEM professionals entering teaching: Navigating multiple identities. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2012, 23, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, L.K.T.; Kushki, A. Exploring career change transitions through a dialogic conceptualization of science teacher identity. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2021, 32, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.; Deaney, R. Changing career and changing identity: How do teacher career changers exercise agency in identity construction? Soc. Psychol. Educ. Int. J. 2010, 13, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molander, B.-O.; Hamza, K. Transformation of professional identities from scientist to teacher in a short-track science teacher education program. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2018, 29, 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, E.A.C.; Smith, E.R.; Steadman, S.; Towers, E. Understanding teacher identity in teachers’ professional lives: A systematic review of the literature. Rev. Educ. 2023, 11, e3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y. Bibliometric review of teacher professional identity over two decades. Sage Open 2024, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermann, S.F.; Meijer, P.C. A dialogic approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2011, 27, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C.; Thomas, L. Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Camb. J. Educ. 2009, 39, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, R.; Olsen, B. Teacher identity in the current teacher education landscape. In Research on Teacher Identity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielewicz, J. Teaching Selves: Identity, Pedagogy, and Teacher Education; University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, M.A. Feeling like a student but thinking like a teacher: A study of the development of professional identity in initial teacher education. J. Educ. Teach. 2020, 46, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.A.; Day, C. Contexts which shape and reshape teacher identities: A multi-perspective study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2006, 22, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luehmann, A. Identity development as a lens to science teacher preparation. Sci. Educ. 2007, 91, 822–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D. Building Teacher Identities: Implications for Preservice Teacher Education. In Proceedings of the Global Issues and Local Effects: The Challenge for Educational Research, Proceedings of the Australian Association for Research in Education Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 29 November–2 December 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kolde, K.; Meristo, M. A second career teacher’s identity formation: An autoethnography study. Int. J. Adult Community Prof. Learn. 2020, 27, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grier, J.M.; Johnston, C.C. An inquiry into the development of teacher identities in STEM career changers. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2009, 20, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, A.; Cherry, M.G.; Dickson, R. (Eds.) Doing A Systematic Review: A Student’s Guide; Sage: Washington DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, P.A. Methodological guidance paper: The art and science of quality systematic reviews. Rev. Educ.Res. 2020, 90, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lai, C. Identity in ESL-CSL career transition: A narrative study of three second-career teachers. J. Lang. Identit. Educ. 2022, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyri, H.; Mostafa, N. From practicum to the second year of teaching: Examining novice teacher identity development. Camb. J. Educ. 2023, 53, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heijst, I.; Cornelissen, F.; Volman, M. Coping strategies used by second-career student teachers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 94, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, C.; Comber, C. ‘Elite’ career-changers in the teaching profession. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 41, 1010–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A. Second career teachers and (mis) recognitions of professional identities. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2016, 36, 221–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivkovic, P. Second-career teachers’ professional identity and imposter phenomenon: Nexus and correlates. J. Educ. Sci. Psychol. 2021, 11, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colliander, H. The experienced newcomer: The (trans) forming of professional teacher identity in a new landscape of practices. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 69, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Hallam, S. From leisure to work: Amateur musicians taking up instrumental or vocal teaching as a second career. Music Educ. Res. 2011, 13, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M.; Miguel, L.; Kwee, C.T.T. Second Career Teachers’ Identity through Schools and Supervisors: A Qualitative Study. In Proceedings of the Australian Teacher Education Association Conference 2023, Sydney, Australia, 12–14 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Sage: Washington DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tigchelaar, A.; Brouwer, N.; Korthagen, F. Crossing horizons: Continuity and change during second-career teachers’ entry into teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 1530–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, J.; Gao, X. “At least I’m the type of teacher I want to be”: Second-career English teachers’ identity formation in Hong Kong secondary schools. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2009, 37, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antink-Meyer, A.; Brown, R.A. Second-career science teachers’ classroom conceptions of science and engineering practices examined through the lens of their professional histories. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2017, 39, 1511–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A. Teacher induction, identity, and pedagogy: Hearing the voices of mature early career teachers from an industry background. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 43, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, J.J.; Diezmann, C.M. Challenges confronting career-changing beginning teachers: A qualitative study of professional scientists becoming science teachers. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2015, 26, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navy, S.L.; Jurkiewicz, M.A.; Kaya, F. Developmental journeys from teaching experiences to the teaching profession: Cases of new secondary science teachers. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2021, 33, 664–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwartz, G.; Dori, Y. Transition into teaching: Second career teachers’ professional identity. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2020, 16, em1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthagen, F. In search of the essence of a good teacher: Towards a more holistic approach in teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2004, 70, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. The recalcitrant self. In The Goffman Reader; Lemert, C., Branaman, A., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1997; pp. 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholtz, M.; Hall, K. Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Stud. 2005, 7, 585–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkington, J. Becoming a teacher: Encouraging development of teacher identity through reflective practice. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2005, 33, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Maanen, J.; Barley, S.R. Occupational communities: Culture and control in organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 1984, 6, 287–365. [Google Scholar]

- Britzman, D. Practice Makes Practice: A Critical Study of Learning to Teach; University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.; Demetriou, H. New teacher learning: Substantive knowledge and contextual factors. Curric. J. 2007, 18, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, C.R.; Scott, K.H. The development of the personal self and professional identity in learning to teach. In Handbook of Research on Teacher Education: Enduring Questions and Changing Contexts; Cochrane-Smith, M., Fieman-Nemser, S., McIntyre, D.J., Demers, K.E., Eds.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 732–755. [Google Scholar]

- Taijfel, H.; Turner, J. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 2nd ed.; Worchel, S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Nelson-Hall: Newton, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.; Kreiner, G.; Fugate, M. All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro-transitions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 25, 472–491. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/259305 (accessed on 1 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oysermann, D. Identity-based motivation and consumer behavior: Response to commentary. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, T. Self and identity. In Handbook of Social Psychology; DeLamater, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 205–233. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker, P.; Burke, P. The past, present and future of an identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2006, 63, 284–297. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2695840 (accessed on 1 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative learning as discourse. J. Transform. Educ. 2003, 1, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. A motivational approach to self: Integration in personality. In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Perspectives on Motivation; Dienstbier, R., Ed.; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1991; Volume 38, pp. 237–288. [Google Scholar]

- Billett, S. Learning in the Workplace: Strategies for Effective Practice; Crows Nest: Sydney, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Billett, S. Subjectivity, self and personal agency in learning through and for work. In The Sage Handbook of Workplace Learning; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.G.; Carter, G. Science teacher attitudes and beliefs. In Handbook of Research on Science Education; Abell, S.K., Lederman, N.G., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 1067–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, N. Science teachers’ beliefs and practices: Issues, implications and research agenda. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2009, 4, 25–48. Available online: https://www.ijese.com/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Varghese, M.; Morgan, B.; Johnston, B.; Johnson, K. Theorizing language teacher identity: Three perspectives and beyond. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 2005, 4, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weedon, C. Feminist Practice and Poststructuralist Theory, 2nd ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Barkhuizen, G. Language teacher identity research: An introduction. In Reflections on Language Teacher Identity Research; Barkhuizen, G., Ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Laclau, E.; Mouffe, C. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics; Verso: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lampert, M. Learning teaching in, from, and for practice: What do we mean? J. Teach. Educ. 2010, 61, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization 2000, 7, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, J.P. Identity as an analytic lens for research in education. Rev. Res. Educ. 2000, 25, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, W.-M.; Tobin, K. (Eds.) Science, Learning, Identity: Sociocultural and Cultural-Historical Perspectives; Sense: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saka, Y.; Sutherland, S.A.; Kittleson, J.; Hutner, T. Understanding the induction of a science teacher: The interaction of identity and context. Res. Sci. Educ. 2013, 43, 1221–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, B. Teaching for Success: Developing Your Teacher Identity in Today’s Classroom; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zembylas, M. Emotions and teacher: A poststructural perspective. Teach. Teach. 2003, 9, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, C.; Busher, H.; Kakos, M.; Mohamed, C.; Smith, J. Crossing borders: New teachers co-constructing professional identity in performative times. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2011, 38, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, Y.; Stuart, C. Learning to become a second language teacher: Identities-in-practice. Mod. Lang. J. 2011, 95, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, R.A. “I’ve not got a job, sir; I’m only teaching”: Dynamics of teacher identity in an era of globalization. CICE Ser. 2011, 4, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C. New lives of teachers. Teach. Educ. Q. 2012, 39, 7–26. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23479560 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Avraamidou, L. Studying science teacher identity: Current insights and future research directions. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2014, 50, 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, B. How reasons for entry into the profession illuminate teacher identity development. Teach. Educ. Q. 2008, 35, 23–40. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23478979 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Beijaard, D.; Meijer, P.C.; Verloop, N. Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2004, 20, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, R.W. The BSCS 5E Instructional Model: Creating Teachable Moments; NSTA Press: Arlington, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schuck, S. Foreword. In Career Change Teachers: Bringing Work and Life Experience to the Classroom; Varadharajan, M., Buchanan, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Grier-Reed, T.L.; Skaar, N.R.; Conkel-Ziebell, J.L. Constructivist career development as a paradigm of empowerment for at-risk culturally diverse college students. J. Career Dev. 2009, 35, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. Career construction: A developmental theory of vocational behavior. In Career Choice and Development, 4th ed.; Brown, D., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 149–205. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M.L.; Nota, L.; Rossier JDauwalder, J.; Duarte, M.E.; Guichard, J.; Soresi, S.; Van Esbroeck, R.; van Vianen, A.E.M. Life-changing: A paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 75, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.A.; Collin, A. Introduction: Constructivism and social constructivism in the career field. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiman-Nemser, S. From preparation to practice: Designing a continuum to strengthen and sustain teaching. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2001, 103, 1013–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERO. Ready, Set, Teach: How Well Prepared and Supported Are New Teachers? Te Ihuwaka Education Evaluation Centre: Wellington, New Zealand, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- den Hertog, G.; Louws, M.; van Rijswijk, M.; van Tartwijk, J. Utilising previous professional expertise by second-career teachers: Analysing case studies using the lens of transfer and adaptive expertise. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 133, 104290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fütterer, T.; van Waveren, L.; Hübner, N.; Fischer, C. I can’t get no (job) satisfaction? Differences in teachers’ job satisfaction from a career pathways perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 121, 103942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucksnat, C.; Richter, E.; Schipolowski, S.; Hoffmann, L.; Richter, D. How do traditionally and alternatively certified teachers differ? A comparison of their motives for teaching, their well-being, and their intention to stay in the profession. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 177, 103784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsdottir, S.; Shulman, L. Pedagogical content knowledge for Social Studies. Scandanavian J. Educ. Res. 1987, 31, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Gobbo, G. Afterword. In Teaching as a Second Career: Non-Traditional Pathways and Professional Development Strategies for Teachers; Frison, D., Dawkins, D.J., André, B., Eds.; Pensa: Lecce, Italy, 2023; pp. 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Tigchelaar, A.; Brouwer, N.; Vermunt, J. Tailor-made: Towards a pedagogy for educating second-career teachers. Educ. Res. Rev. 2010, 5, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Guitart, M. Funds of identity. In Encyclopaedia of Critical Psychology; Teo, T., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charteris, J.; Thomas, E.; Masters, Y. Funds of identity in education: Acknowledging the life experiences of first year tertiary students. Teach. Educ. 2018, 53, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlossberg, N.K. A model for analysing human adaption to transition. Couns. Psychol. 1981, 9, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlossberg, N.K. Counselling Adults in Transition: Linking Practice with Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Baeten, M.; Meeus, W. Training second-career teachers: A different student profile, a different training approach? Educ. Process Int. J. 2016, 5, 173–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterich, C.A.; Panton, C.L. Motivations of post-baccalaureate students seeking teacher certification: A context for appropriate advising strategies. J. Career Dev. 1996, 22, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martinez, I.; Tadeu, P. The influence of pedagogical leadership on the construction of professional identity: Systematic review. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 2018, 9, 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Coppe, T.; Sarazin, M.; März, V.; Dupriez, V.; Raemdonck, I. (Second career) teachers’ work socialization as a networked process: New empirical and methodological insights. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 116, 103766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppe, T.; März, V.; Raemdonck, I. Second career teachers’ work socialization process in TVET: A mixed-method social network perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 121, 103914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, H. Working Identity: Unconventional Strategies for Reinventing Your Career, 2nd ed.; Harvard Business School Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Caspari-Gnann, I.; Sevian, H. Teacher dilemmas as a source of change and development. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 112, 103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Morrison, C. Teacher identity and early career resilience: Exploring the links. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2011, 36, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Robb, A. An exploration of the role of creative industries experience in the pedagogical practice of second-career teachers. Creat. Ind. J. 2024, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: Westport, CT, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D. Organizational Learning: A Theory in Action Perspective; Addison-Westley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Eraut, M. Teacher education designed or framed. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2000, 33, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werler, T.C.; Tahirsylaj, A. Differences in teacher education programmes and their outcomes across Didatik and curriculum traditions. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2022, 45, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theoretical Frameworks | Citing Study | Research Questions of Citing Study |

|---|---|---|

| Onion model of teacher ID [53]. | Tigchelaar et al. [46] | What are the characteristic differences between CCSTs and FCSTs, when they enter ITE? What are the characteristics in which CCSTs differ from each other? Which experiences of continuity and change do CCTs report during their transition to teaching? In what respects do CCTs experience their ITE as supportive for the transition to teaching? |

| ID through identification (engagement, imagination, alignment) and negotiability [54]; Typology of responses to conflict and/or marginalization [55]; Discursive identity construction [27]; Indexicality and relationality in discourse [56]. | Trent and Gao [47] | How is teacher identity constructed by English language CCTs in secondary schools in Hong Kong? |

| Teacher identity and functional role as not mutually exclusive [57]; Identity is demonstrated through the use of professional vocabulary, demonstrating skills, and taking responsibility [58]; Teacher ID through engagement, imagination, and alignment [54]. | Grier and Johnston [33] | What professional teaching goals and identities do CCSTs bring with them into ITE? What are the common elements or traits math and science CCSTs possess? What is the process by which math and science CCSTs develop their teacher identity? |

| ITE as teacher ID [59]; ID through reflection and discursive practice in authentic teaching situations (e.g., [60]); Teacher identity as assigned by self and others [27]; Sociocultural influences on dynamic, non-linear ID in ITE [61]; Teacher identity both doing teaching work and being a teacher [31]; Teacher ID includes aligning oneself with groups that support [62], and validate chosen identity [63]; Self-concept and agency in ID [64,65]; Self-concept [66]; Resolving multiple identities in ID [67]. | Wilson and Deaney [20] | How do CCTs exercise agency in identity construction? |

| Identity trajectories into, within, and out of communities of practice [54]. | Grier and Johnston [18] | What do CCSTs express as their needs in the learning-to-teach process as they transition between careers? In what ways do CCSTs’ previous multiple identities influence their beliefs about teaching during the learning-to-teach process? |

| Transformative learning theory [68]. | Synder et al. [14] | What cognitive and emotional transformations do STEM CCTs experience when transitioning into secondary science teaching? |

| Self-determination theory [69]; Career engagement theory [70]. | Watters and Diezmann [50] | What early career experiences contribute to or hinder the development of a sense of professional identity as science CCTs with subject-matter expertise? In what ways do these experiences influence the CCTs’ decisions to remain in teaching? |

| Workplace learning [71,72]. | Green [49] | How do CCTs form their identity as new teachers? How do CCTs adapt to their role as new teachers? What are CCTs’ own thoughts in relation to their new careers? |

| Sociocultural conceptualizations of teacher knowledge and beliefs [73]; Complex, and sometimes conflicting, beliefs as a framework to sort and prioritize knowledge [74]. | Antink-Meyer and Brown [48] | What do science CCTs perceive as best practice in science teaching? How do science CCTs perceive professional science and engineering, and how do they perceive the relationship between their former STEM-related work practices and the science and engineering practices in their classrooms? |

| Language teacher ID through identity-in-discourse and identity-in-practice [75]; Identity-in-discourse impacts on positioning, interpretation, and decisions [76]; Teacher ID characterized by what people do, in terms of engagement, imagination, and alignment [54]; ID informed by multiple, possibly contested identities (e.g., [77]); Fluidity of discourses and identities [78]. | Trent [15] | How do CCTs in Hong Kong construct their identities in discourse and in practice? |

| Professional teacher ID within ITE focuses on being a teacher, rather than doing the work of a teacher [79]; ID as belonging and participating within a community of practice, developed in social interaction [54,80,81]; ID as tied to historical, institutional, and sociocultural forces [82], applied to language teacher identity development [30]; ID as dynamic and resulting from interaction within social practices [83] and discursive activities, and from recognition and acceptance by others [84]. | Molander and Hamza [21] | What, regarding teaching and coursework, is highlighted and talked about by CCSTs with a science background throughout their ITE? Does CCSTs’ focus of attention concerning aspects of their ITE change over time, and if so how? Can these changes be related to the design of the ITE program? |

| ID via reconciliation of personal and professional factors [85]; ID influenced by both personal and contextual factors [82,85]. | Shwartz and Dori [52] | Which identity resources (practices, norms, and professional standards) implemented in their ITE did chemistry CCTs perceive as supportive in (a) shaping their professional identity as novice teachers; and (b) providing tools to integrate their knowledge and skills into teaching chemistry? |

| Teacher self-formation related to (1) the teaching role/tasks and (2) the teaching identity (related to core beliefs) [31]; Role of emotions in teachers’ ID [86]; Teacher ID within school communities [87]; Teacher ID through classroom practice [88]; Teacher ID as product of sociocultural context and dominant ideology [89]. | Kolde and Meristo [32] | How did a novice CCT experience her teaching self? |

| “The part the person plays within the professional” (p. 15) [90]; Identity as a process (not product) (e.g., [91,92]): dynamic and emergent, and situated within contexts [93]; Dialogical approach to teacher identity conceptualization [24]. | Smetana and Kushki [19] | What aspects of identity were revealed as two CCTs decided to change careers? What moments of disequilibrium did these CCTs experience during the transition from one career to another? How did these CCTs restore equilibrium? |

| Career transitions as sites of teacher ID and learning [16]; Constructivist orientations of learning and development [94,95]; Constructivist career development theories [96,97]; Role of valued meaning and benefits [98,99]; Linear progression within teacher development [100]. | Navy et al. [51] | How do CCSTs draw upon their prior science-related and teaching-related career experiences as they develop as teachers during ITE? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hogg, L.M.; Elvira, Q.; Yates, A.S. Identity Development of Career-Change Secondary Teachers: A Systematic Review of Theoretical Lenses, Emerging Identities, and Implications for Supporting Transition into Teaching. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080857

Hogg LM, Elvira Q, Yates AS. Identity Development of Career-Change Secondary Teachers: A Systematic Review of Theoretical Lenses, Emerging Identities, and Implications for Supporting Transition into Teaching. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(8):857. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080857

Chicago/Turabian StyleHogg, Linda Mary, Quincy Elvira, and Anne Spiers Yates. 2024. "Identity Development of Career-Change Secondary Teachers: A Systematic Review of Theoretical Lenses, Emerging Identities, and Implications for Supporting Transition into Teaching" Education Sciences 14, no. 8: 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14080857