Abstract

Effective communication between students and instructors is vital for student success. Traditionally, this communication has taken place in person within classroom settings. However, with technological advancements, online classes have become more common. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this shift, significantly disrupting traditional communication methods between students and instructors and transforming the educational landscape, particularly in higher education. We conducted a qualitative narrative literature review of the technological tools that emerged during the pandemic and explored how today’s instructors can effectively use them to enhance student engagement and motivation in online classrooms. The review utilized the SANRA (scale for the assessment of narrative reviews) guidelines to ensure the quality of the studies used. Twenty-two articles published within the last ten years were chosen based on their relevance to higher education and student–instructor communication. The articles were analyzed for effective and ineffective educational communication tools (e.g., Zoom or Google Classroom) utilized during the pandemic, focusing on what worked and what could be improved. The findings revealed that live video sessions were more effective than pre-recorded videos, voice-only sessions, or email/text communications in fostering student engagement and motivation.

1. Introduction

Higher education has been experiencing unparalleled turbulence, driven by technological advancements, shifting demographics, and evolving student needs (). Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated these changes, compelling educational institutions worldwide to convert traditional in-person classes to online classes to protect their employees and students (; ; ; ; ). Online learning has become increasingly prevalent in higher education, as many institutions, even previously resistant ones, now offer classes online (; ). Thus, e-learning has become a fundamental educational tool in the post-pandemic world (; ).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the lack of high-speed internet connections posed a significant barrier in the United States, especially for low-income families (). This issue was notably acute for students living in impoverished areas, many of whom are Black and Hispanic (). These students often had to use their cell phones for internet access, which severely limited their educational opportunities (). This highlights the technological disparities that affect online learning and the need for equitable access to resources in higher education, but it is hardly the only problem highlighted by the pandemic educational crisis.

1.1. The Link Between Effective Communication and Student Engagement/Motivation

In addition to the technological challenges, keeping students engaged and motivated in the online learning environment was also challenging (; ; ). Effective communication is one of the critical elements in education (). Whereas communication can simply be defined as transmitting information from one source to the intended recipients, () note that communication in an educational context is dynamic and interactive. Ideas, information, and values are all exchanged between instructors and students, and the aim of those exchanges is to foster understanding, enhance learning, and help students achieve their educational objectives. To do this effectively, communication must go beyond simple verbal exchanges, using non-verbal cues, teaching resources, and digital technologies, all of which help promote understanding and achieve learning outcomes (). Effective communication is especially essential for higher education, as it fosters positive learning experiences, enhances student motivation, and builds a rapport between instructors and learners from diverse backgrounds (). It makes students more confident, promotes greater student engagement, and helps them learn actively during class. Regular communication also helps instructors understand students’ needs, allowing them to support their students based on individual challenges (). Instructors and students communicate verbally and non-verbally in a classroom, and when an instructor communicates directly, students are motivated to work hard in class (). This interaction helps them remain motivated not only during the class but also after class. Communication also helps build motivation among students, which is very important for learning ().

Students can also significantly improve their skills by communicating effectively with other students (). If students can build positive relationships with motivated peers, they encourage each other to push to new heights. Communication in the classroom, thus, fosters understanding, empathy, and skill development (). A scholarly study by Chang and Hall points out that students can also achieve social goals by becoming more engaged in the classroom, a process that instructors can influence by keeping them motivated (). Furthermore, this study shows that students are more active in class and academic activities when communicating effectively with their instructors and can experience professional and personal growth ().

Unfortunately, while technology enabled the continuation of education during the pandemic, it did not always support effective instructor–student communication, raising challenges in building a strong rapport (; ). Establishing effective communication remains one of the primary challenges in online learning, particularly in higher education. This lack of effective communication was detrimental to the instructor–student relationship, negatively impacting students’ grades, motivation, academic progress, and overall learning (; ). Academic success was clearly affected by this lack of rapport and student engagement (). Additionally, face-to-face instruction allows the instructor to gauge student understanding based on body language cues, which are not always available online (). Furthermore, many factors, such as inadequate school support, a challenging social environment, low family income, and students’ limited learning levels, can hinder the effectiveness of online learning. Addressing these issues is important to ensure quality education (). COVID-19’s profound impact on instructor–student communication in higher education has forced instructors to rely heavily on online educational platforms (; ). However, research indicates that before the COVID-19 pandemic, only 16% of instructors had experience teaching classes online, and a substantial 94% required additional training in information and communication technology (ICT) ().

1.2. Other Factors Affecting Student Engagement and Motivation

The surge in online learning forced higher education instructors to seek out new educational tools that could enhance communication, motivation, and engagement (). They began to use digital tools such as gamification to create more engaging lessons, provide quick feedback to students, and encourage group activity (; ), thus working to establish a sense of community in the online platforms. However, motivation and engagement were not the only challenges instructors faced. Azmi et al. found that 79% of the students felt more fear about their examinations during the pandemic (), which was exacerbated by the fact that 75% reported experiencing symptoms of depression during the COVID-19 lockdown. This research also highlights that female students reported higher levels of stress compared to their male counterparts (). Students experiencing mental health challenges often have problems completing academic tasks in a satisfactory manner, which is why it is helpful to understand what they may be going through (). While instructors cannot take on the role of mental health counselor, they can reach out to students and encourage a dialogue about fearful events that may be impacting student motivation and engagement with course materials.

Kanuka suggests that with these ongoing changes driven by technological advancements, educators must rethink online teaching methods to ensure that online learning meets students’ academic and emotional needs through effective communication (). Rudick and Golsan stress the crucial role of understanding the sociocultural and contextual dimensions of communication between students and instructors, as this understanding is essential for improving the online learning environment (). While higher education has the potential to be revolutionized by online learning, its success depends largely on the effectiveness of communication between students and instructors (). The present research explores the following topics: (1) the most effective communication methods for increasing student engagement and motivation in higher education online classes, (2) the key factors and platforms influencing student engagement in online learning, (3) effective communication and student engagement, (4) the key factors influencing student motivation in higher education, (5) the impact of design elements in online courses on student engagement and motivation, and (6) the strategies for improving online learning in higher education.

This study aims to highlight the best-practice strategies for addressing gaps in online course instruction to increase student engagement and motivation. This is critical for those students and instructors who continue to actively use online platforms as well as for creating an effective system that can be used in future crises, such as that presented by a pandemic.

2. Methodology

We conducted a narrative review by systematically searching two databases, JSTOR and Google Scholar, to identify relevant studies on the effectiveness of online teaching methods, student engagement, and motivation during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Boolean operators were used to refine the search process and identify relevant literature.

2.1. Search Strategy

The Boolean operators used in the search strategy are outlined below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search strategy using Boolean operators.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The studies included in this review were selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in Table 2. This approach ensured that only the most relevant and recent articles were considered for this research.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.3. Review Process

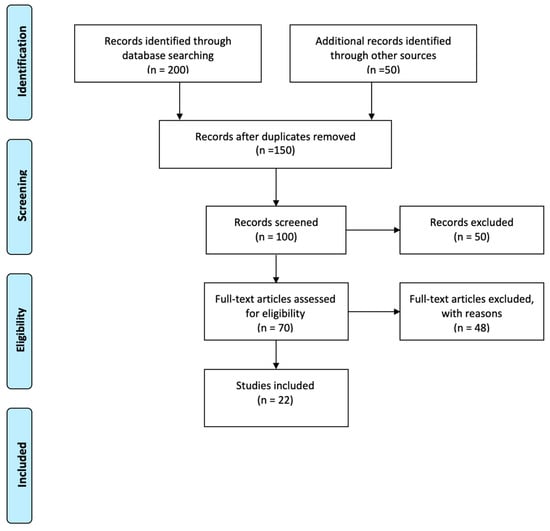

The initial screening of articles involved reviewing abstracts, introductions, and conclusions, which were used during the initial review to ensure relevancy and compliance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A further in-depth qualitative analysis was then conducted. Duplicate studies were removed during this phase. The review process followed the SANRA (scale for the assessment of narrative review articles) guidelines to ensure the quality of the selected studies (). A total of 22 studies were included in this review after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria and removing duplicates. The screening process was documented using a PRISMA-ScR diagram () to provide a clear overview of the study selection.

3. Results

Screening Results

Of the 250 articles retrieved, only 22 met the selection criteria. Figure 1 shows the study selection process for inclusion in this review.

Figure 1.

(PRISMA-ScR) Diagram of the included studies.

The 22 selected studies utilized a variety of methodologies, including review papers, quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. Table 3 summarizes each study’s country, aim, method type, and key findings.

Table 3.

Data charted from 22 articles.

The themes from this review were analyzed to understand their role in online education. Table 4 provides a summary of these critical areas.

Table 4.

Summary of key themes in online education.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effective Communication Methods in Higher Education Online Courses

Numerous research studies, including the work of (), have explored various factors that influence college students’ academic performance in online classes. This is important since instructors have become more dependent on digital technologies to communicate with students since the pandemic, and this trend shows no signs of slowing. Online higher education classes use two communication methods: synchronous or real-time () and asynchronous or pre-recorded (). Both methods have advantages and disadvantages regarding communication, but synchronous classes tend to be preferred in terms of effectiveness.

Some synchronous options include e-labs, e-lectures, discussion forums, and chat rooms (). These options allow students to feel a sense of community, which helps them reduce their feelings of isolation during online classes. Furthermore, a recent study found that synchronous classes are preferable for delivering lectures since students get real-time feedback, facilitating a clearer understanding of the subject matter. This real-time interaction helps students feel comfortable and relaxed, promoting active participation (). Research further suggests synchronous classes have better interaction and engagement because seeing the instructor’s face during an online video class can significantly increase student engagement. Thus, in university settings, where independent learning is essential, seeing the instructor’s face in synchronous courses facilitates the overall learning experience (). Synchronous online lectures are commonly conducted using Microsoft Teams, Google Classroom, Google Meet, and Zoom. These platforms offer advanced features, such as real-time polling and breakout rooms, which further enrich the classes ().

A notable school experiment was conducted in China with 1024 participants from two schools with similar conditions (). They used two different online teaching methods in the school: one was an asynchronous recorded video, and the other was a synchronous online live class. The students reported that the live online class helped them learn better than the pre-recorded videos. In online courses, instructors were the leaders of the class; they could talk and guide the students when required, which was missing in pre-recorded videos (). The study also found that pre-recorded videos negatively impacted student performance, especially for those who did poorly in exams and were already struggling with learning (). For example, the study found that the pre-recorded video significantly decreased academic achievement by 1.6 percentage points. The study also indicates that asynchronous classes are mainly self-guided, which is an obstacle for lower-ability students who struggle because there is no direct instructor feedback (). Furthermore, students struggle more in the first three weeks of the semester than in the middle and later weeks. Thus, early live sessions are crucial for a solid learning experience ().

However, asynchronous online education methods, such as forum discussions, pre-recorded lectures, and email exchanges, have also become popular. Pre-recorded lectures and other study materials are now permanent resources for students (). Learners can revisit study materials at their convenience, enhancing the overall student learning experience. Therefore, although synchronous learning helps students engage more effectively in the online classroom, asynchronous methods can also motivate students, especially if structured appropriately. For example, instructors can use graded discussion posts, facilitate sessions for peer feedback, and allow students to check in with instructors occasionally. This approach will ensure active participation in asynchronous classes ().

For students who find learning more accessible and are more self-motivated, their learning outcome is not different between asynchronous and synchronous classes (). Additionally, Northey et al. found that if students actively participated in either a synchronous or asynchronous online learning forum, they demonstrated higher engagement and better academic outcomes than those students attending face-to-face classes only (). This suggests that student participation may play a more prominent role regardless of the type of online learning method and indicates that student participation is more critical than the manner in which the class was delivered. This emphasizes the value of student engagement regardless of the online class format ().

Students who are not proficient in technology can still feel demotivated in online classes (), even if they see the instructor’s face, and thus may feel they learn less. This highlights the need for higher education institutions to ensure that students have sufficient technical support in cases where they run into trouble. Students need adequate training and support to engage fully in the classroom. Institutions can facilitate this by offering regular workshops and video tutorials on using educational apps and websites. A 24/7 online help desk is also crucial to empower learners to effectively navigate online learning platforms ().

Educational institutions should also integrate student feedback for a better understanding. Case studies, for example, can provide a more comprehensive view. Students have different preferences; some like synchronous classes for their features, such as providing real-time feedback, while others like asynchronous learning, as this method allows for flexibility (). This indicates that educational institutions need to adopt mixed methods, and, in fact, many higher education institutions use the ’blended learning’ approach, combining live sessions with asynchronous features. This approach is helpful as it allows learners to advance in both formats (; ). Thus, higher educational institutions should take a multi-faceted approach to involve learners in online class participation and provide strong technological support to promote active communication between instructor and student in synchronous and asynchronous classes.

4.2. Key Factors and Platforms Influencing Student Engagement in Higher Education

According to (), there are three types of engagement in the context of online education. The first is behavioral engagement, in which students actively participate in online learning activities. A student’s participation, interaction, collaboration, achievement, skill development, and learning activity completion are all part of behavioral engagement (). The second type of engagement is known as cognitive engagement, which is when students show motivation for learning online and when they are able to demonstrate self-regulated learning. Cognitive engagement reflects a student’s ability to think critically and reflect on what they are learning, which ultimately leads to the ability to understand complex concepts (). Finally, emotional engagement refers to a student’s positive attitude about their online learning experience. Also known as affective engagement, this includes their attitude toward the instructor, their peers, and the course material, as well as the value they assign to the subject matter and the learning circumstances. Their emotional connection to the material, if positive, leads to feelings of satisfaction and well-being ().

With the rise of online learning in higher education, understanding the factors contributing to student engagement has become increasingly important. () noted that five variables are essential for differentiating between synchronous and asynchronous settings. These are (1) communication tools, (2) feedback types, (3) input methods, (4) collaboration modes, and (5) targeted skills (). When considering these variables, the authors note that researchers found that university students were more satisfied with asynchronous communication tools, such as discussion forums and email, but that they also appreciated the availability of direct instructor feedback that is present in the synchronous classroom (). In asynchronous classrooms, the quality of the learner–content interactions, such as watching videos, and the learner–instructor interactions, such as providing summative and formative assessments and documenting student progress, strongly affected learner satisfaction (). However, students tend to perceive certain activities, such as online discussions, as being more individualistic and less collaborative in the asynchronous setting, which is associated with negative learning outcomes and a decreased sense of belonging ().

In the synchronous university classroom, students felt that their participation was more focused, which resulted in a stronger sense of contribution (). They found that the live nature of the synchronous classroom increased their motivation, resulting in better course performance. By attending live online courses, college students can directly interact with their instructor and ask questions in real time, which is why most students prefer to join a live online class rather than an asynchronous class (). Moreover, the collaborative nature of these synchronous classes, where students work with their peers, can enhance the learning experience and increase the students’ sense of belonging, an essential factor for motivation and engagement ().

The requirement to attend the live online course also fosters a stronger sense of responsibility in university students, enhancing their motivation and making them feel more accountable for their learning (). With real-time instructor feedback, students tend to be more engaged and motivated. They are also more interested in classes where professors use visual aids and non-verbal communication. Asking questions during the class enhances student engagement, as does the integration of educational technology to support interaction and collaboration among students (). It is also crucial for instructors to provide frequent and direct feedback whenever possible, as this has a significant impact on learning outcomes in the synchronous classroom. In the asynchronous course, timely feedback is more challenging to deliver but remains equally important (). In short, instructors must carefully select appropriate technology and teaching methods to maintain student engagement in online classrooms, as well as choose the most suitable platform for delivering content effectively.

Microsoft Teams and Google Meet became essential online learning platforms during the pandemic (). One key advantage of Microsoft Teams is its seamless integration with the Microsoft Office suite, which enables collaborative work on various documents and supports real-time presentation. This fosters collaboration among instructors and students, promoting direct communication, enhancing productivity, and encouraging more active engagement in online learning. Similarly, Google Meet is well known for its user-friendly features for students. It is easy to navigate even for students with limited tech knowledge and helps them quickly join online classes ().

During the pandemic, Google Classroom played a vital role in sustaining educational continuity for universities. In the post-pandemic world, it continues to support institutions by serving as an essential platform for hybrid and online courses. According to Gupta and Pathania, Google Classroom offers structured ongoing and continuous interactions that effectively support university students’ diverse academic needs (). By enhancing the virtual learning environment, Google Classroom positively impacts the instructor–student relationship. It also helps maintain consistent connections between instructors and students, which was very helpful for student satisfaction during the pandemic (). According to Inoue and Pengnate, both students and instructors find that Google Classroom requires less effort compared to other platforms (). Additionally, instructors and students can use Google Classroom entirely for free, and instructors can quickly create an online classroom and have live conversations with their students ().

Zoom has become a leading platform for communication between instructors and college students as higher education institutions transitioned to online learning environments during and after the pandemic. Although there are a variety of platforms for instructors to deliver lectures, Zoom remains one of the preferred choices for online teaching (). Like other online platforms, it supports real-time lessons and enables document sharing. Instructors and students can see each other’s facial expressions, which promotes active participation and rapport building. Using an open camera reinforces students’ engagement in the online class, as visual interaction is essential for a positive learning experience. Research shows that students who used cameras during the class were more engaged in the classroom, whereas those who turned the camera off were not. This indicates a strong association between the frequency of camera use during Zoom classrooms and student engagement levels (). Students, in general, found that Zoom facilitated communication with instructors and collaboration with classmates. Some popular features, like breakout rooms that support group study and a live chat, facilitate discussion during class, which greatly contributes to creating a collaborative learning environment ().

Although live classes on platforms like Zoom offer several motivational benefits, they also come with notable challenges (). Technical issues are one of the biggest challenges, such as poor internet connectivity, which may lead to feelings of inadequacy in students. Students experiencing these issues may encounter interruptions in their learning and a decline in motivation (). This is one of the main reasons why many students prefer face-to-face classes over online classes.

In addition to the method and platform used, many college students struggle to focus on online classes because of the distractions of their family and surroundings (). Furthermore, students with low online skills have trouble communicating effectively with their instructors. This difficulty in communication is one of the primary reasons students struggle to stay engaged, especially in hands-on fields like medicine (). These findings suggest that it is necessary to take a deeper dive into not just the form of course delivery but also the specific types of activation and interaction to promote student engagement in both the synchronous and asynchronous courses in higher education (). For example, according to Fabriz et al., the key feature of live classes is live sessions and support, which need to be added to pre-recorded videos. This personalized approach, tailored to each student’s needs, offers a considerable advantage in fostering engagement ().

4.3. Effective Communication and Student Engagement

Effective communication is pivotal in fostering student engagement, with timely and constructive feedback as a cornerstone. Belt and Lowenthal () emphasize that synchronous communication helps create an interactive and personalized learning environment. Synchronous online courses are taught in real time and mimic the face-to-face classroom with active instructor interaction with students and the ability for students to ask questions and receive immediate feedback (). This real-time exchange encourages students to stay engaged with the course content and feel supported in their learning journey. It also creates a sense of community. While asynchronous courses do not offer real-time interactions, prompt instructor feedback and strategies such as weekly summaries and one-on-one sessions with instructors can all help students stay engaged, even without real-time interactions (). Furthermore, feedback in group discussions and collaborative projects, as noted by Northey et al. (), fosters a sense of community and mutual accountability. These collaborative efforts allow students to take ownership of their learning, encouraging active participation and engagement throughout the course.

Moreover, weekly summaries and clarification sessions contribute significantly to student engagement by providing regular checkpoints that help students stay aligned with course objectives. They know they can not fall too far behind without the instructor’s help clarifying the content. It is also helpful for the instructor to keep track of students who may be struggling. () also highlight the importance of clarity in content delivery, noting that consistent updates and clear communication of expectations can significantly enhance student focus and participation. Moreover, digital platforms like Google Classroom and Zoom have become essential tools for promoting engagement, especially in online learning environments. These technologies enable real-time interaction between instructors and students and provide a space for students to collaborate with their peers, ensuring that communication remains active and that all learners stay involved (). Effective communication builds a strong foundation for student success through these methods, encouraging engagement and fostering a supportive learning atmosphere.

4.4. Key Factors Influencing Student Motivation in Higher Education

Motivation is considered to be the driving force that causes students to engage in the learning process (). It is critical in the online learning environment since students must engage in self-regulated learning. A student’s motivation to learn gives them the reason to engage in the learning activities presented in a particular course. Students who are more motivated will be more involved in the course content. They will more frequently engage in the course material and activities. Intrinsic motivation includes a zest for acquiring new knowledge, and those students with this important quality were more likely to report online courses to be motivating (). Several factors contribute to student motivation in online courses within higher education, with access to technology, learning environments, instructor communication styles, and psychological interventions playing significant roles. Bergdahl () highlights that students in underserved communities often face challenges, such as limited access to high-speed internet and digital devices, which can severely hinder their ability to engage in online courses. These technological barriers can lead to decreased motivation, as students may feel disconnected or unable to fully participate. Addressing these challenges is essential to fostering an inclusive learning environment where all students have the tools they need to succeed ().

In addition to technological access, the structure of the course and the quality of feedback are key to enhancing intrinsic motivation, as discussed by (). When courses are well structured, with clear objectives and regular feedback, students are more likely to stay motivated and engaged. Timely and constructive feedback helps students feel supported in their learning journey, fostering a sense of achievement and progress. () emphasizes the importance of instructor communication, particularly the role of empathy in motivating students. When instructors demonstrate empathy and create an emotionally supportive learning environment, students are more willing to participate and feel a deeper connection to the course, which enhances their overall motivation ().

Psychological well-being is also crucial in maintaining motivation, especially in online learning environments. () stress the significance of mental health support, noting that stress and anxiety can detract from a student’s motivation and academic performance. Providing access to counseling services and peer support forums helps alleviate these challenges, offering students the emotional support they need to stay engaged and motivated (). By addressing students’ academic and emotional needs, institutions can help ensure sustained motivation, enabling learners to overcome obstacles and remain committed to their studies (). Lastly, online courses fostering a sense of community can significantly enhance motivation. Social interaction, even in virtual settings, helps create a support network that encourages students to stay engaged (). Collaborative learning, such as group projects and peer discussions, strengthens this sense of community, making students feel less isolated. When students interact with their peers and feel part of a collective learning experience, their intrinsic motivation is often boosted, as they are more likely to persist in the course and take an active role in their learning process ().

4.5. The Impact of Design Elements in Online Courses on Student Engagement and Motivation

The design of online courses plays a critical role in shaping student engagement and motivation. A well-structured and user-friendly interface can significantly reduce cognitive load, allowing students to focus on learning rather than struggling to navigate complex platforms. Tools like Google Classroom and Microsoft Teams are widely praised for their ease of use and collaborative features, helping foster a more engaging learning experience (). These platforms facilitate communication and organization, enabling students to easily access resources, interact with peers, and stay on track with their coursework. In addition, incorporating multimedia elements, such as videos, infographics, and animations, makes learning more dynamic and interactive, essential for maintaining students’ attention and improving comprehension. Belt and Lowenthal () emphasize that multimedia content, particularly in synchronous learning environments, captures attention and boosts participation by providing diverse, stimulating learning experiences.

Another key aspect of course design is accessibility, which ensures that all students, regardless of their backgrounds or abilities, can engage with the material. Features like closed captions, adjustable font sizes, and screen readers help make the course content more inclusive, especially for students with visual or auditory impairments (). By providing these options, online courses can better support a diverse student body and ensure that everyone has the opportunity to succeed. Moreover, incorporating collaborative design elements, such as group assignments, peer reviews, and discussion forums, builds a sense of community and encourages active participation. Gupta and Pathania () note that these features, particularly when integrated into platforms like Google Classroom, can significantly enhance motivation by promoting student interaction and mutual support. Such collaborative environments create opportunities for peer learning, improving academic performance and engagement ().

Using gamification techniques is another powerful tool for enhancing student engagement and motivation in online courses (). Elements like points, badges, and challenges create an interactive and rewarding learning environment that motivates students to stay actively involved in their coursework. According to (), tools like Quizizz and Kahoot! offer immediate feedback and foster both individual and collaborative participation. These gamified elements make learning more enjoyable and reinforce a sense of accomplishment and progress, encouraging students to continue their efforts ().

Furthermore, integrating such tools with collaborative tasks, such as group projects and peer assessments, strengthens the sense of community within the course, fostering more profound engagement (; ). Beyond the interactive and collaborative aspects of course design, the ability for students to track their progress is another factor that boosts motivation. Tools that allow students to monitor their performance, such as progress bars, achievement trackers, and personalized feedback, help them visualize their success and areas for improvement (; ; ). This sense of control and visibility enhances intrinsic motivation, as students can see the tangible results of their efforts. Such tracking tools can also encourage goal setting, enabling students to stay focused on their learning objectives and maintain a steady pace throughout the course (; ).

Finally, course design that includes real-time interaction and instant feedback opportunities is critical for sustaining student motivation. Live sessions, virtual office hours, and synchronous discussions allow students to connect directly with instructors and peers, ensuring they feel supported and engaged (). These real-time interactions promote a dynamic learning environment where students can ask questions, clarify doubts, and build stronger relationships with their instructors and fellow learners. This continuous communication keeps students motivated and enhances their overall learning experience by providing timely guidance and support ().

4.6. Strategies for Improving Online Learning in Higher Education

Based on this literature review, there are several strategies for enhancing online learning in higher educational institutions. The educational community—including students, parents, instructors, and universities—should examine what works for them to make the e-learning experience more academically satisfying for university students. Possible areas for improvement are discussed below.

Firstly, proper professional development for instructors is crucial. Instructors’ beliefs, attitudes, and technological skills significantly impact student engagement (). Universities should provide information and communication technology (ICT) training to equip instructors with essential digital teaching skills. Universities should educate instructors on diverse online teaching methodologies, enabling them to discover which suits their students best and how to use them effectively (). Improving instructor–student collaboration and interaction is another area requiring attention. Instructors can ensure student motivation remains high with regular feedback sessions and check-ins.

Another critical aspect is ensuring equitable technology access for all students. Universities should ensure that each student has devices that support online classes and an uninterrupted internet connection. They should also implement programs to provide technological resources to students from low-income families (). This initiative may need to involve partnerships with local government agencies and businesses to support the necessary infrastructure. Moreover, educational institutions should explore private resources that offer discounted or free technological tools for students in need. Ensuring seamless access to IT support for both students and faculty is also crucial to addressing technical issues promptly ().

The structure of online classes and the overall learning environment play a significant role in student engagement, particularly in higher education settings. Instructors should create and implement structured plans for their online courses. Based on the self-determination theory, Cents-Boonstra et al. observed 120 lessons from 43 instructors (). Their study illustrated how crucial structured instruction and consistent support are for students during class. Their findings showed that structural instruction enhanced student engagement and motivation, whereas a lack of structural instruction resulted in lower engagement and participation. Furthermore, instructors need to be aware of the differences between online courses and in-person classes when administering tests and other types of assessment. Since students can readily access resources at home, instructors should design assessments differently to accurately assess student learning. Promoting a positive and supportive environment during online classes is also crucial, as it can help students navigate the challenges that may arise ().

Engagement in live online classes can be improved by establishing supportive norms and attitudes at both the individual and institutional levels. Universities should encourage the entire educational community to enhance engagement in live online courses (). Instructors are also encouraged to give proper instructions for assignments to keep students engaged, as online learning tends to be more independent (). It is also helpful to routinely record synchronous courses so students can replay the course later if needed. Additionally, instructors should provide timely feedback and track student progress to ensure an effective learning experience, regardless of the delivery format ().

Policy development is another crucial area for enhancing online learning in higher educational settings. Institutions should allocate sufficient funds to develop comprehensive policies tailored to online education needs. For example, policies promoting respectful online interactions are essential for students to feel safe expressing themselves (). Moreover, policies should require basic digital literacy for students and instructors so they feel comfortable using technology. It is also vital to have policies regulating technology use in the classroom, such as the use of AI tools and search engines like Google, and policies regarding plagiarism and student attendance. Such policies must align with the institutional values related to new technologies. Additionally, policies need to be in place to ensure online education quality, including established course assessment methods to ensure the learning objectives are met by the course material and techniques to evaluate instructor interactions with students and course materials ().

Lastly, providing emotional support for college students is a crucial factor in facilitating the transition to online learning (). Many college students experienced high levels of anxiety and stress during and after the pandemic, which negatively affected their motivation in online classes (). Universities should allocate funds specifically for mental health services and promote accessible online forums. This support system will allow students to share their experiences, fostering a sense of community and empathy. These measures can positively impact students’ motivation and promote academic performance. Universities should support their students emotionally through counseling and by creating online communities where students can share their experiences and provide emotional support to each other (). Instructors should encourage students to interact more with peers through these forums to enrich their learning experiences.

4.7. Recommendations for Future Research

More research needs to be conducted on the efficacy of various e-learning platforms. Additional studies could help identify more efficient and effective methods for training instructors in using e-technologies. While anecdotal evidence suggests that humanizing asynchronous courses helps keep students engaged, this needs to be supported by qualitative and quantitative research. This also emphasizes the importance of instructor training in effectively teaching online courses.

Moreover, investigating how institutional policies affect instructor and student motivation and engagement may clarify which approaches are successful and which are not. It is also essential for researchers to recognize that successful e-learning strategies may vary according to the level of education and the age of the students. For example, effective strategies in the university setting may be fundamentally different from those in the K-12 setting, and approaches for older students may not be as helpful for younger pupils. Examining differences in e-learning strategies could inform educational institutions’ decisions. Additionally, research on the influence of sociocultural factors on the success of online learning programs might help address the needs of diverse cultural settings. E-learning approaches may need to be adapted when working with students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds compared to those from middle or upper classes.

As part of this investigation, it would also be beneficial to research how instructors can adjust their communication strategies to support students prone to anxiety. Some of the research presented in this study indicates that students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to feel anxious when taking an online course. For effective e-learning, instructors should be prepared to address the unique needs of students from diverse backgrounds. A hybrid model may be one viable solution. This is an area where much research is still needed to determine the best communication and e-learning strategies. Another prime area of research is the use of AI technologies and how they can benefit the online classroom in terms of student engagement and motivation. It is vital to fully understand how students use AI and, in turn, how instructors in online courses can adapt their strategies to ensure student learning objectives are genuinely being achieved rather than simply reflecting the capabilities of AI technology.

More research must be conducted to understand how infrastructure limitations affect student engagement and motivation. When students experience connectivity issues, it may dampen their enthusiasm for learning, and research must assess the extent of this impact and explore potential solutions. Finally, research on establishing a quality review process for online courses is crucial to help universities monitor and improve their success in meeting learning objectives.

4.8. Limitations of the Current Review

One limitation of the current study is that the articles chosen for review were only those published in English. A more thorough review might consider publications in other languages as well. Furthermore, only articles published in the last ten years were considered. Although this time frame captures publications on much of the recent technology in online learning, some foundational principles of effective instruction may have yet to be identified. The inclusion criteria for the current study also did not consider articles that were not directly focused on online learning. Some of these studies, such as those on alternative learning methods, could offer valuable insights for enhancing e-learning strategies.

Moreover, the present study focused only on college students. Investigating other learning populations, such as K-12 students, might yield different results regarding their unique needs and challenges. It should also be acknowledged that the rapid implementation of online courses due to the pandemic may have introduced biases in the results. The pandemic also created stressors not typically experienced by students of all ages, which could have affected these findings. Another limitation of the present study is the disciplinary context of any particular online learning course. This may limit the generalizability of the findings, given that student motivation and engagement can vary significantly depending on the subject being taught. For example, STEM courses engage students differently than humanities courses, given the complexity of the content and the variation in teaching methods. Without examining specific disciplines, the conclusions of this review may not apply equally to all online courses. Finally, with the rapid evolution of online technology, some results may quickly become outdated.

5. Conclusions

With the increasing shift toward digital learning and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, online education has become widely popular. This paper examines its challenges, limitations, benefits, and potential areas for improvement. This study found that synchronous teaching methods were more effective than asynchronous methods for students, as they are better at promoting active participation, which in turn fostered student engagement and motivation. Synchronous classes also helped instructors serve as leaders and facilitators, enhancing student interaction. However, some asynchronous tools, such as forums and emails, were perceived as superior in certain aspects. Furthermore, many asynchronous teaching methods, such as pre-recorded lectures, have become indispensable for today’s students. It is essential to note that consistent access to technology was crucial for maintaining student motivation in both methods.

This paper also identified key factors that promote student engagement in online classes, such as interactive platforms and clear communication strategies, both of which are essential in synchronous and asynchronous methods. However, students still preferred synchronous classes as they tended to be more focused and felt a stronger sense of responsibility, participation, and contribution. The ability of professors to respond in real time to students’ visual and non-visual cues was also highly valued for students in live synchronous courses. In short, synchronous online courses significantly enhanced students’ engagement, rapport, and communication, all of which are critical to their academic success.

A personalized approach that combines both synchronous and asynchronous methods could further enhance student performance. Popular platforms for online classes, including Google Classroom, Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, and Zoom, enable this personalized approach. Instructors should familiarize themselves with these platforms to determine the most suitable options. The present research also identified key areas for improvement; training instructors in essential digital and online teaching skills is among the most critical. On the other hand, ensuring all students have access to the necessary technology and devices is vital to providing equitable education. Structured classes are also important for student engagement, a crucial factor in academic success. Engagement can also be enhanced with consistent feedback and open communication.

Policy development is another critical area to ensure safe online environments, appropriate evaluation tools, and technological proficiency. Lastly, though equally important, is to provide emotional support for students. By following these recommendations, educators can significantly enhance student engagement and motivation in online classrooms. These steps will also help establish a strong foundation for an educational system that can adapt to emergencies requiring remote learning.

Higher education institutions must continue to explore and implement innovative communication strategies and teaching approaches to ensure online learning is both engaging and effective. Academic institutions need to equip instructors and students with the comprehensive resources and support necessary to cultivate a positive online learning environment. Instructors can significantly improve student engagement and motivation in online classes by actively addressing student concerns, fostering clear communication, and humanizing their courses. They should reach out to students regularly to solicit feedback rather than waiting for issues to arise. This proactive approach will help students feel more supported and valued, positively affecting academic outcomes and contributing to more inclusive educational experiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D.D.; methodology, P.D.D.; software, P.D.D.; validation, P.D.D. and Y.C.; formal analysis, P.D.D.; investigation, P.D.D.; resources, P.D.D., Y.C. and M.S.R.; data curation, N.G.; writing—original draft preparation, P.D.D.; writing—review and editing, Y.C., N.G. and M.S.R.; visualization, P.D.D.; supervision, Y.C. and M.S.R.; project administration, P.D.D., Y.C. and M.S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Akargöl, İ., Karadağ, İ., & Gürcan, Ö. F. (2024). Selecting the optimal e-learning platform for universities: A pythagorean fuzzy AHP/TOPSIS evaluation. The European Journal of Research and Development, 4, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M., Al-Mamun, M., Pramanik, M. N. H., Jahan, I., Khan, M. R., Dishi, T. T., Akter, S. H., Jothi, Y. M., Shanta, T. A., & Hossain, M. J. (2022). Paradigm shifting of education system during COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study on education components. Heliyon, 8, e11927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, M., Alharbi, M., & Alodwani, A. (2019). The effect of social-emotional competence on children academic achievement and behavioral development. International Education Studies, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, F. M., Khan, H. N., & Azmi, A. M. (2022). The impact of virtual learning on students’ educational behavior and pervasiveness of depression among university students due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Health, 18, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C., Goldbeck-Wood, S., & Mertens, S. (2019). SANRA—A scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrot, J. S., Llenares, I. I., & del Rosario, L. S. (2021). Students’ online learning challenges during the pandemic and how they cope with them: The case of the Philippines. Education and Information Technologies, 26, 7321–7338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belt, E. S., & Lowenthal, P. R. (2023). Synchronous video-based communication and online learning: An exploration of instructors’ perceptions and experiences. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 4941–4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergdahl, N. (2022). Engagement and disengagement in online learning. Computers & Education, 188, 104561. [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent, J., & Lodge, J. (2021). Use of live chat in higher education to support self-regulated help seeking behaviours: A comparison of online and blended learner perspectives. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmi, G. (2024). E-Learning using zoom: A study of students’ attitude and learning effectiveness in higher education. Heliyon, 10, e30229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cents-Boonstra, M., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., Denessen, E., Aelterman, N., & Haerens, L. (2021). Fostering student engagement with motivating teaching: An observation study of teacher and student behaviours. Research Papers in Education, 36, 754–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. -F., & Hall, N. C. (2022). Differentiating teachers’ social goals: Implications for teacher–student relationships and perceived classroom engagement. AERA Open, 8, 23328584211064916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankseliani, M., Qoraboyev, I., & Gimranova, D. (2021). Higher education contributing to local, national, and global development: New empirical and conceptual insights. Higher Education, 81, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S. Y., & Ng, K. Y. (2021). Application of the educational game to enhance student learning. Frontiers in Education, 6, 623793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayal, S. (2023). Online education and its effect on teachers during COVID-19—A case study from India. PLoS ONE, 18, e0282287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deep, P. D., Ghosh, N., Gaither, C., & Koptelov, A. V. (2024). Gamification techniques and the impact on motivation, engagement, and learning outcomes in ESL students. RAIS Journal for Social Sciences, 8, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- del Rio, C., & Malani, P. N. (2020). COVID-19—New insights on a rapidly changing epidemic. JAMA, 323, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabriz, S., Mendzheritskaya, J., & Stehle, S. (2021). Impact of synchronous and asynchronous settings of online teaching and learning in higher education on students’ learning experience during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 733554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S., Shafi Malik, M., Jabeen, F., & Nabeel, S. A. (2024). Social science review archives communication barriers between teachers-students during teaching learning process at secondary school level. Social Science Review Archives, 2, 1435–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopika, J. S., & Rekha, R. V. (2023). Awareness and use of digital learning before and during COVID-19. International Journal of Educational Reform, 105, 67879231173389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A., & Pathania, P. (2021). To study the impact of google classroom as a platform of learning and collaboration at the teacher education level. Education and Information Technologies, 26, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Händel, M., Stephan, M., Gläser-Zikuda, M., Kopp, B., Bedenlier, S., & Ziegler, A. (2022). Digital readiness and its effects on higher education students’ socio-emotional perceptions in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J. E., & Carr, B. G. (2020). Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19. New England Journal of Medicine, 382, 1679–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollister, B., Nair, P., Hill-Lindsay, S., & Chukoskie, L. (2022). Engagement in online learning: Student attitudes and behavior during COVID-19. Frontiers in Education, 7, 851019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M., & Pengnate, W. (2018, May 17–18). Belief in foreign language learning and satisfaction with using Google classroom to submit online homework of undergraduate students. 2018 5th International Conference on Business and Industrial Research (ICBIR) (pp. 618–621), Bangkok, Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- Kanuka, H. (2022). Trends in higher education. Trends in Higher Education, 1, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K. (2022). Pre-recorded lectures, live online lectures, and student academic achievement. Sustainability, 14, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemay, D. J., Bazelais, P., & Doleck, T. (2021). Transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 4, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, H. (2020). Best practices for implementing remote learning during a pandemic. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 93, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray-Garcia, J., Ngo, V., & Garcia, E. F. (2023). COVID-19’s still-urgent lessons of structural inequality and child health in the United States. Journal of the National Medical Association, 115, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimavat, N., Singh, S., Fichadiya, N., Sharma, P., Patel, N., Kumar, M., Chauhan, G., & Pandit, N. (2021). Online medical education in India—Different challenges and probable solutions in the age of COVID-19. Online medical education in India–different challenges and probable solutions in the age of COVID-19. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 12, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northey, G., Bucic, T., Chylinski, M., & Govind, R. (2015). Increasing student engagement using asynchronous learning. Journal of Marketing Education, 37, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuryana, Z., Xu, W., Kurniawan, L., Sutanti, N., Makruf, S. A., & Nurcahyati, I. (2023). Student stress and mental health during online learning: Potential for post-COVID-19 school curriculum development. Comprehensive Psychoneuroendocrinology, 14, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Doherty, D., Dromey, M., Lougheed, J., Hannigan, A., Last, J., & McGrath, D. (2018). Barriers and solutions to online learning in medical education—An integrative review. BMC Medical Education, 18, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, S. Z. M. (2022). Combining synchronous and asynchronous learning: Student satisfaction with online learning using learning management systems. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 9, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., & Jefferson, F. (2019). A comparative analysis of student performance in an online vs. face-to-face environmental science course from 2009 to 2016. Frontiers in Computer Science, 1, 472525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Photopoulos, P., Tsonos, C., Stavrakas, I., & Triantis, D. (2022). Remote and in-person learning: Utility versus social experience. SN Computer Science, 4, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plakhotnik, M. S., Volkova, N. V., Jiang, C., Yahiaoui, D., Pheiffer, G., McKay, K., Newman, S., & Reißig-Thust, S. (2021). The perceived impact of COVID-19 on student well-being and the mediating role of the university support: Evidence from France, Germany, Russia, and the UK. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 642689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. (2023). The post COVID-19 pandemic era: Changes in teaching and learning methods for management educators. The International Journal of Management Education, 21, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudick, C. K., & Golsan, K. B. (2014). Revisiting the relational communication perspective: Drawing upon relational dialectics theory to map an expanded research agenda for communication and instruction scholarship. Western Journal of Communication, 78, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusakova, O., Tamozhska, I., Tsoi, T., Vyshotravka, L., Shvay, R., & Kapelista, I. (2023). The changes in teacher-student interaction and communication in higher education institutions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Pilco, S. Z., Yang, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2022). Student engagement in online learning in Latin American higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53, 593–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanmugam, M., Mohd Zaid, N., Mohamed, H., Abdullah, Z., Aris, B., & Md Suhadi, S. (2015). Gamification as an educational technology tool in engaging and motivating students; An analyses review. Advanced Science Letters, 21, 3337–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. (2022). Conceptual framework on smart learning environment—An Indian perspective. Revista de Educación y Derecho, (25). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skochelak, S. E., & Stack, S. J. (2017). Creating the medical schools of the future. Academic Medicine, 92, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobaih, A. E. E., Palla, I. A., & Baquee, A. (2022). Social media use in e-learning amid COVID 19 pandemic: Indian students’ perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., & Hempel, S. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagino, W., Maksum, H., Purwanto, W., Simatupang, W., Lapisa, R., & Indrawan, E. (2024). Enhancing learning outcomes and student engagement: Integrating e-learning innovations into problem-based higher education. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (iJIM), 18, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y., Hu, Y., Wu, C., Yang, L., & Lei, M. (2022). Challenges of online learning amid the COVID-19: College students’ perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1037311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F. (2022). Fostering students’ well-being: The mediating role of teacher interpersonal behavior and student-teacher relationships. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 796728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).