Do Educators’ Demographic Characteristics Drive Learner Academic Performance? Examining the Role of Gender, Qualifications, and Experience

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- i.

- Analyse the relationship between educator qualifications and learner academic performance.

- ii.

- Evaluate the effect of educator demographic factors (gender, age, and experience) on learner academic performance.

- iii.

- Compare the relative influence of demographic characteristics and professional qualifications on learner academic performance.

- iv.

- Assess the validity of Mincer’s Earnings Function in capturing diminishing returns to experience.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework and Model Specification

2.1.1. Theoretical Framework

2.1.2. Model Specification

2.2. Development of Hypotheses and Techniques of Estimation

2.2.1. Development of Hypotheses

2.2.2. Techniques of Estimation and Information About the Data

3. Presentation of Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

3.1.1. Frequency of Demographic Data

3.1.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.2. Regression Analysis

3.3. Ethical Considerations

4. Discussion of Results and Evaluation of Hypotheses

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Demographic Variables | Category | Number (N) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

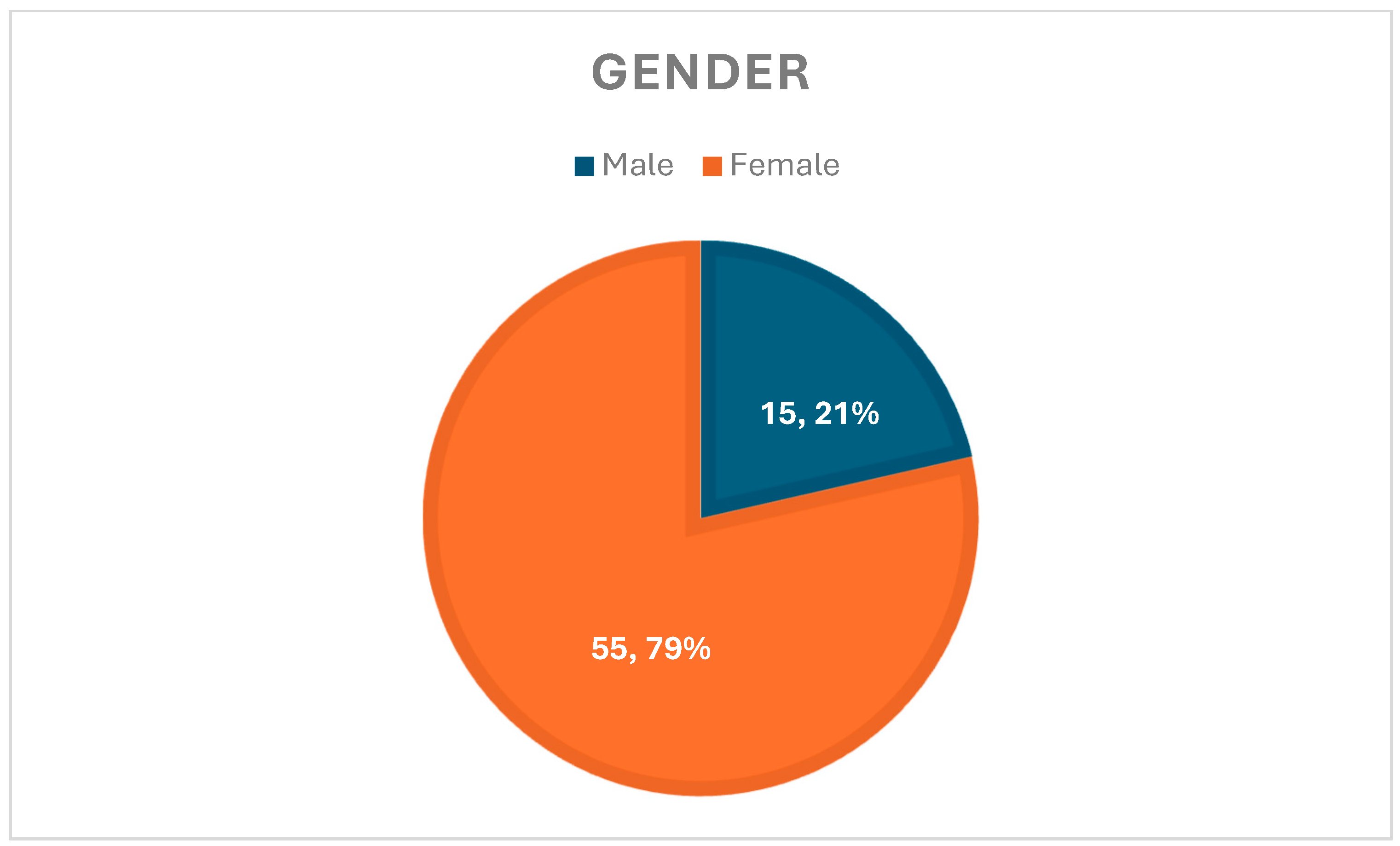

| Gender | Male | 15 | 21% |

| Female | 55 | 79% | |

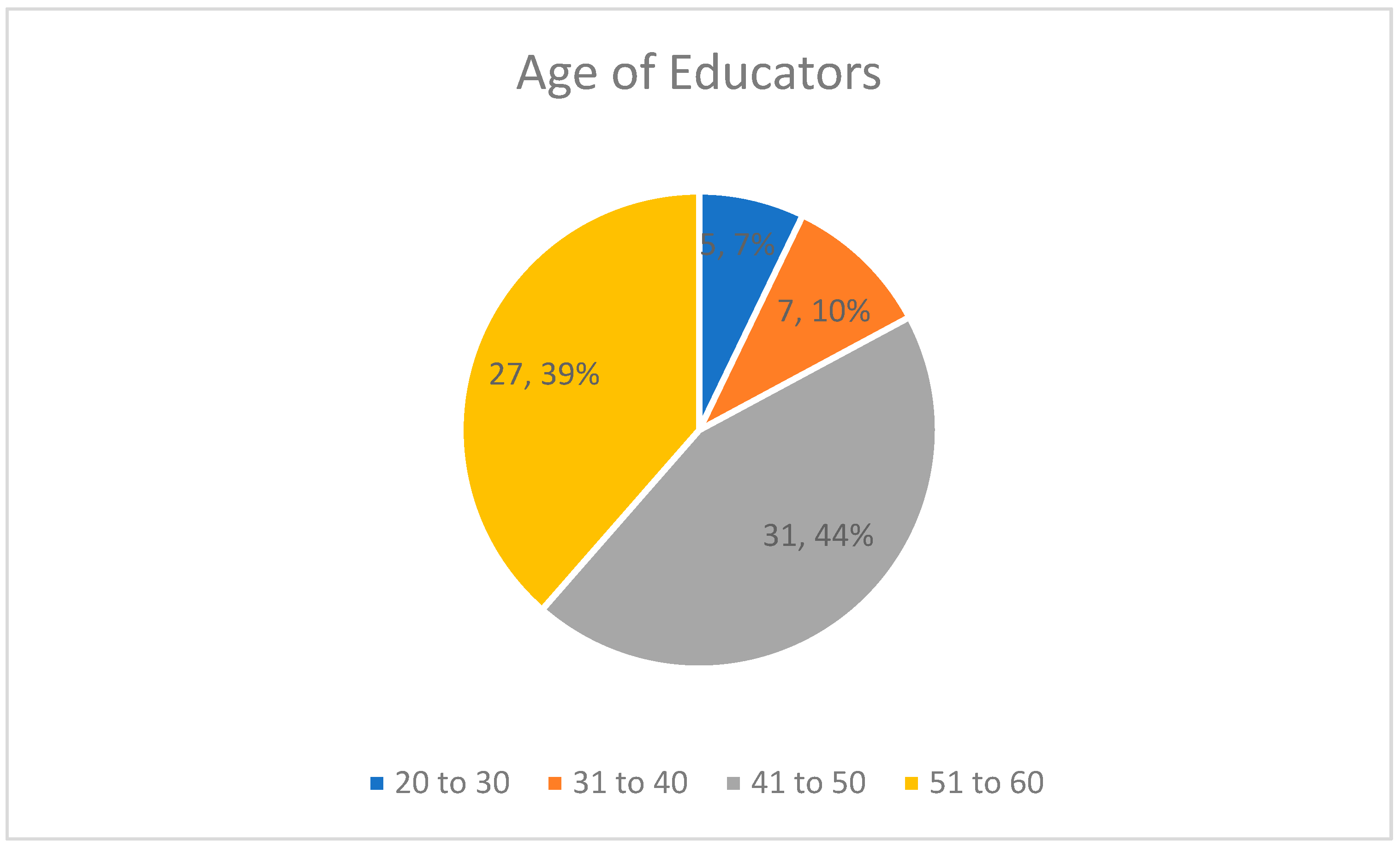

| Age of Educators | 20 to 30 | 5 | 7% |

| 31 to 40 | 7 | 10% | |

| 41 to 50 | 31 | 44% | |

| 51 to 60 | 27 | 39% | |

| Work Experience | 1 to 10 | 17 | 24% |

| 11 to 20 | 33 | 47% | |

| 21 to 30 | 12 | 17% | |

| 31 upwards | 8 | 12% | |

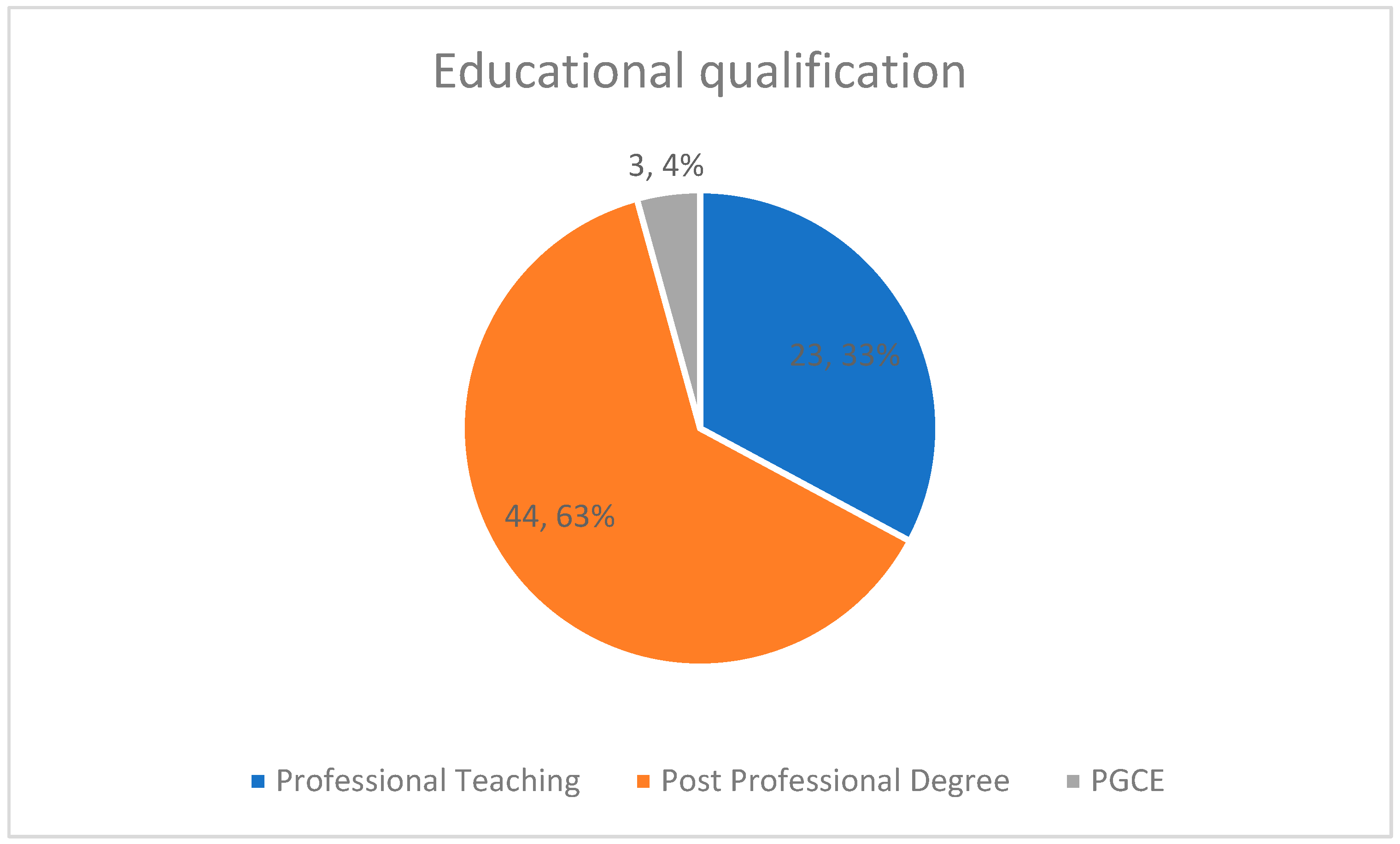

| Educational Qualification | Professional Teaching | 23 | 33% |

| Post-Professional Degree | 44 | 63% | |

| PGCE | 3 | 4% |

| Variance Inflation Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Included Observations: 70 | |||

| Coefficient | Uncentered | Centred | |

| Variable | Variance | VIF | VIF |

| AGE | 0.015351 | 941.0617 | 2.685725 |

| EXPERIENCE SQUARED | 0.002922 | 139.9551 | 4.79229 |

| EXPERIENCE | 0.010853 | 319.307 | 2.49493 |

| MALE = 1 | 0.000296 | 1.30058 | 1.040464 |

| MALE = 0 | 0.000678 | 5.202321 | 0.020103 |

| QUALIFICATION | 0.198539 | 5782.749 | 1.376684 |

| C | 0.273385 | 6004.058 | NA |

References

- Abou-Khalil, V., Helou, S., Khalifé, E., Chen, M. A., Majumdar, R., & Ogata, H. (2021). Emergency online learning in low-resource settings: Effective student engagement strategies. Education Sciences, 11(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimov, A., Malin, M., Sargsyan, Y., Suyunov, G., & Turdaliev, S. (2024). Student success in a university first-year statistics course: Do students’ characteristics affect their academic performance? Journal of Statistics and Data Science Education, 32(1), 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaleye, A. J., & Ncanywa, T. (2025). Complexity of Renewable energy and technological innovation on gender-specific labour market in South African economy. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 11, 100492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaleye, A. J., Ojo, A. P., & Olagunju, O. E. (2023). Asymmetric and shock effects of foreign AID on economic growth and employment generation. Research in Globalization, 6, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B., & Zang, X. (2025). Bilingual learning motivation and engagement among students in Chinese-English bilingual education programmes in Mainland China: Competing or coexistent? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baikady, R. (2025). Social Work Pedagogy. In Advancing global social work: A machine-generated literature overview (pp. 101–151). Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, A., Kohli, N., & Madyibi, S. (2024). Grade repetition, school drop-out and ineffective school policy. EDUCATIO: Journal of Education, 9(2), 81–93. Available online: https://ejournal.staimnglawak.ac.id/index.php/educatio/article/view/1514 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Beard, K. S., & Thomson, S. I. (2021). Breaking barriers: District and school administrators engaging family, and community as a key determinant of student success. Urban Education, 56(7), 1067–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capita. National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online: http://digamo.free.fr/becker1993.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Brink, H. W., Loomans, M. G., Mobach, M. P., & Kort, H. S. (2021). Classrooms’ indoor environmental conditions affecting the academic achievement of students and teachers in higher education: A systematic literature review. Indoor Air, 31(2), 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Careemdeen, J. D. (2024). Influence of Parental Income and Gender on Parental Involvement in the Education of Secondary School Children in Sri Lanka: A Comprehensive Investigation. e-BANGI Journal, 21(1), 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirowamhangu, R. (2024). Rights-based analysis of basic education in South Africa. Journal for Juridical Science, 49(3), 110–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J., McKenzie, S., Schweinsberg, A., & Mundy, M. E. (2022). Correlates of academic performance in online higher education: A systematic review. Frontiers in Education, 7, 820567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M. (2021). Exploring teacher quality: International perspectives. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3), 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantine, E., Mwinjuma, J. S., & Nemes, J. (2025). Assessing the influence of socio-demographic characteristics on teachers’ resilience in Tanzania: A study of selected secondary schools in Morogoro Municipality. Educational Dimension, 1–18. Available online: https://acnsci.org/journal/index.php/ed/article/view/842 (accessed on 19 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dahri, N. A., Yahaya, N., Al-Rahmi, W. M., Vighio, M. S., Alblehai, F., Soomro, R. B., & Shutaleva, A. (2024). Investigating AI-based academic support acceptance and its impact on students’ performance in Malaysian and Pakistani higher education institutions. Education and Information Technologies, 29, 18695–18744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilowicz-Gösele, K., Lerche, K., Meya, J., & Schwager, R. (2017). Determinants of students’ success at university. Education Economics, 25(5), 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Basic Education. (2025). 2020 national senior certificate examination report. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/2021NSCExamReports.aspx?utm_source (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2023). Expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: Reflections on the legacy of 40+ years of working together. Motivation Science, 9(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, D. W. (2012). Learning theories and historical events affecting instructional design in education: Recitation literacy toward extraction literacy practices. Sage Open, 2(4), 2158244012462707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Even, U., & BenDavid-Hadar, I. (2025). Teachers’ perceptions of their school principal’s leadership style and improvement in their students’ performance in specialised schools for students with conduct disorders. Management in Education, 39(1), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, A. R. S. (2020). Teachers’ personal and professional demographic characteristics as predictors of students’ academic performance in English. Online Submission, 5(2), 80–91. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED608431 (accessed on 19 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gentrup, S., Lorenz, G., Kristen, C., & Kogan, I. (2020). Self-fulfilling prophecies in the classroom: Teacher expectations, teacher feedback and student achievement. Learning and Instruction, 66, 101296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbatkin, E., Nguyen, T. D., Strunk, K. O., Burns, J., & Moran, A. J. (2025). Should I stay or should I go (later)? Teacher intentions and turnover in low-performing schools and districts before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Finance and Policy, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J. (2023). Visible learning: The sequel: A synthesis of over 2,100 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M., & Raza, A. (2024). Examining academic achievement of elementary school students: A gender-based study. International Journal of Contemporary Issues in Social Sciences, 3(1), 966–972. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, L. E., Dar-Nimrod, I., & MacCann, C. (2018). Teacher personality and teacher effectiveness in secondary school: Personality predicts teacher support and student self-efficacy but not academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(3), 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, N. (2023). Investigating school-level and out-of-school factors influencing the performance at selected secondary schools in the Eastern Cape Province, Amathole west district. Available online: https://uwcscholar.uwc.ac.za/items/582b7ead-1f0e-4c74-bfe4-e80a13b4b5a0 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Langer, S. (2025). Bridging the digital divide: Empowering seniorsand adults with low literacy through digital literacy. Revista DH/ED: Derechos Humanos y Educación, (11), 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Leech, N. L., & Haug, C. A. (2015). Teacher workforce: Understanding the relationship among teacher demographics, preparation programs, performance, and persistence. Research in the Schools, 22(1), 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lowther, D. L., Ross, S. M., & Morrison, G. M. (2003). When each one has one: The influences on teaching strategies and student achievement of using laptops in the classroom. Educational Technology Research and Development, 51, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucksnat, C., Richter, E., Henschel, S., Hoffmann, L., Schipolowski, S., & Richter, D. (2024). Comparing the teaching quality of alternatively certified teachers and traditionally certified teachers: Findings from a large-scale study. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 36(1), 75–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Alguacil, N., Avedillo, L., Mota-Blanco, R., & Gallego-Agundez, M. (2024). Student-Centered Learning: Some Issues and Recommendations for Its Implementation in a Traditional Curriculum Setting in Health Sciences. Education Sciences, 14(11), 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincer, J. A. (1974). The human capital earnings function. In schooling, experience, and earnings (pp. 83–96). NBER. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c1767/c1767.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Mosia, M., Egara, F. O., Nannim, F., & Basitere, M. (2025). Bayesian growth curve modelling of student academic trajectories: The impact of individual-level characteristics and implications for education policy. Applied Sciences, 15(3), 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulawarman, W. G., & Komariyah, L. (2021). Women and leadership style in school management: Study of gender perspective. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 16(2), 594–611. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1297011 (accessed on 19 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mullola, S., Jokela, M., Ravaja, N., Lipsanen, J., Hintsanen, M., Alatupa, S., & Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. (2011). Associations of student temperament and educational competence with academic achievement: The role of teacher age and teacher and student gender. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(5), 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtonen, M., Aldahdouh, T. Z., Vilppu, H., Trang, N. T. T., Riekkinen, J., & Vermunt, J. D. (2024). Importance of regulation and the quality of teacher learning in student-centred teaching. Teacher Development, 28, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R. A., & Smith, J. (2004). Chapter 11 Determinants of educational success in higher education. In International handbook on the economics of education (p. 415). Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncanywa, T., Lose, T., & Nguza-Mduba, B. (2022, September 14–16). Transformation in Institutions of higher education in South Africa: An entrepreneurial ecosystem perspective. International Conference on Public Administration and Development Alternatives (IPADA), Johannesburg, South Africa. Available online: https://univendspace.univen.ac.za/items/11cf03e4-d3fc-4673-bc47-fbd62207bd25 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Ngobeni, N. R., Chibambo, M. I., & Divala, J. J. (2023). Curriculum transformations in South Africa: Some discomforting truths on interminable poverty and inequalities in schools and society. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1132167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkepah, B. D. (2025). Gender-Based Variances in Student Interest and Commitment to Mathematical Tasks in Secondary Schools in Bamenda Municipality. International Journal of Mathematics and Mathematics Education, 3(1), 18–32. Available online: https://journals.eduped.org/index.php/IJMME/article/view/1238 (accessed on 19 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nnadozie, R. C. (2024). Monitoring and evaluation implications of the 2014 regulations for reporting by public higher education institutions in South Africa. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2302580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogujiuba, K., Maponya, L., & Stiegler, N. (2024). Determinants of human development index in South Africa: A comparative analysis of different time periods. World, 5(3), 527–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patfield, S., Gore, J., & Harris, J. (2023). Shifting the focus of research on effective professional development: Insights from a case study of implementation. Journal of Educational Change, 24(2), 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priadi, G., Umari, T., Donal, D., & Mansor, R. (2023). Gender Differences in Student Resistance towards Teachers: A Comparative Study Between Male and Female Students. Jurnal Psikologi Terapan (JPT), 6(1), 9–17. Available online: https://ojs.unimal.ac.id/jpt/article/view/11327 (accessed on 19 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Province of Eastern Cape Education. (2023). 2022 NSC grade 12 class report card. Available online: https://eceducation.gov.za/files/content/1674307706_iBWklBySEs_2022-RESULTS-ANYALSIS-FOR-2022_V1-.pdf?utm_source (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Redding, C. (2019). A teacher like me: A review of the effect of student-teacher racial/ethnic matching on teacher perceptions of students and student academic and behavioural outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 89(4), 499–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redding, C., & Carlo, S. M. (2025). Superintendent turnover and student achievement: A two-state analysis. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 01623737241310837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L. A., Nguyen, T. D., & Springer, M. G. (2025). Revisiting teaching quality gaps: Urbanicity and disparities in access to high-quality teachers across Tennessee. Urban Education, 60(2), 467–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, D. L., & Jak, S. (2024). Gender match in secondary education: The role of student gender and teacher gender in student-teacher relationships. Journal of School Psychology, 107, 101363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A., Gath, M. E., Gillon, G., McNeill, B., & Ghosh, D. (2024). Facilitators of success for teacher professional development in literacy teaching using a micro-credential model of delivery. Education Sciences, 14(6), 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, S., & Fletcher-Wood, H. (2021). Identifying the characteristics of effective teacher professional development: A critical review. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 32(1), 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C., & Gillespie, M. (2023). Research on professional development and teacher change: Implications for adult basic education. In Review of adult learning and literacy (Vol. 7, pp. 205–244). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Snoek, M. (2021). Educating quality teachers: How teacher quality is understood in the Netherlands and its implications for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3), 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sok, S., & Heng, K. (2024). Research on teacher education and implications for improving the quality of teacher education in Cambodia. International Journal of Professional Development, Learners and Learning, 6(1), ep2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaull, N. (2013). Poverty & privilege: Primary school inequality in South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 33(5), 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, A., Božić, R., & Radović, S. (2021). Higher education students’ experiences and opinion about distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(6), 1682–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolk, J. D., Gross, M. D., & Zastavker, Y. V. (2021). Motivation, pedagogy, and gender: Examining the multifaceted and dynamic situational responses of women and men in college STEM courses. International Journal of STEM Education, 8(1), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronge, J. H. (2018). Qualities of effective teachers. Ascd. [Google Scholar]

- Tadese, M., Yeshaneh, A., & Mulu, G. B. (2022). Determinants of good academic performance among university students in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C. Y. (2024). Socioeconomic status and student learning: Insights from an umbrella review. Educational Psychology Review, 36(4), 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatto, M. T. (2021). Professionalism in teaching and the role of teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(1), 20–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timotheou, S., Miliou, O., Dimitriadis, Y., Sobrino, S. V., Giannoutsou, N., Cachia, R., Monés, A. M., & Ioannou, A. (2023). Impacts of digital technologies on education and factors influencing schools’ digital capacity and transformation: A literature review. Education and Information Technologies, 28(6), 6695–6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witter, M., & Hattie, J. (2024). Can teacher quality be profiled? A cluster analysis of teachers’ beliefs, practices and students’ perceptions of effectiveness. British Educational Research Journal, 50(2), 653–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldegiorgis, E. T., & Chiramba, O. (2024). Access and success in higher education: Fostering resilience in historically disadvantaged students in South Africa. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 17(2), 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xholo, N., Ncanywa, T., Garidzirai, R., & Asaleye, A. J. (2025). Promoting Economic Development Through Digitalisation: Impacts on Human Development, Economic Complexity, and Gross National Income. Administrative Sciences, 15(2), 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Carter, R. A., Jr., Zhang, J., Hunt, T. L., Emerling, C. R., Yang, S., & Xu, F. (2024). Teacher perceptions of effective professional development: Insights for design. Professional Development in Education, 50(4), 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Observation | Mean | Std. Error | Std. Deviation | Variance | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 70 | 3.14 | 0.104 | 0.873 | 0.762 | 0.150 | −1.000 |

| Experience | 70 | 2.16 | 0.111 | 0.927 | 0.859 | 0.250 | −0.800 |

| Qualification | 70 | 1.41 | 0.069 | 0.577 | 0.333 | 0.002 | −1.200 |

| Gender | 70 | 1.21 | 0.049 | 0.413 | 0.171 | 1.400 | 0.001 |

| Academic Performance | 70 | 2.53 | 0.139 | 1.164 | 1.354 | −0.350 | −0.500 |

| Academic Performance | Gender | Age | Experience | Qualification | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Performance | 1000 | ||||

| Gender | 0.002 (0.9868) | 1000 | |||

| Age | 0.124 (0.3664) | 0.155 (0.2001) | 1000 | ||

| Experience | −0.051 (0.6750) | 0.062 (0.6101) | 0.258 (0.0311) | 1000 | |

| Qualification | 0.317 (0.0075) | −0.135 (0.2652) | 0.025 (0.8372) | −0.015 (0.9019) | 1000 |

| Least Squares Estimate | ||||

| Included Observations: 70 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Learner Academic Performance | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| AGE | 0.193841 | 0.123898 | 1.564516 | 0.1226 |

| EXPERIENCE SQUARED | −0.14207 | 0.054054 | −2.628285 | 0.0107 |

| EXPERIENCE | 0.196921 | 0.104178 | 1.890246 | 0.0633 |

| QUALIFICATION | 0.183375 | 0.445577 | 0.411545 | 0.682 |

| MALE = 0 | 1.15718 | 0.522863 | 2.213164 | 0.0305 |

| MALE = 1 | 1.16328 | 0.525677 | 2.212915 | 0.0305 |

| R-squared | 0.51497 | Durbin–Watson stat | 2.199801 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.483367 | |||

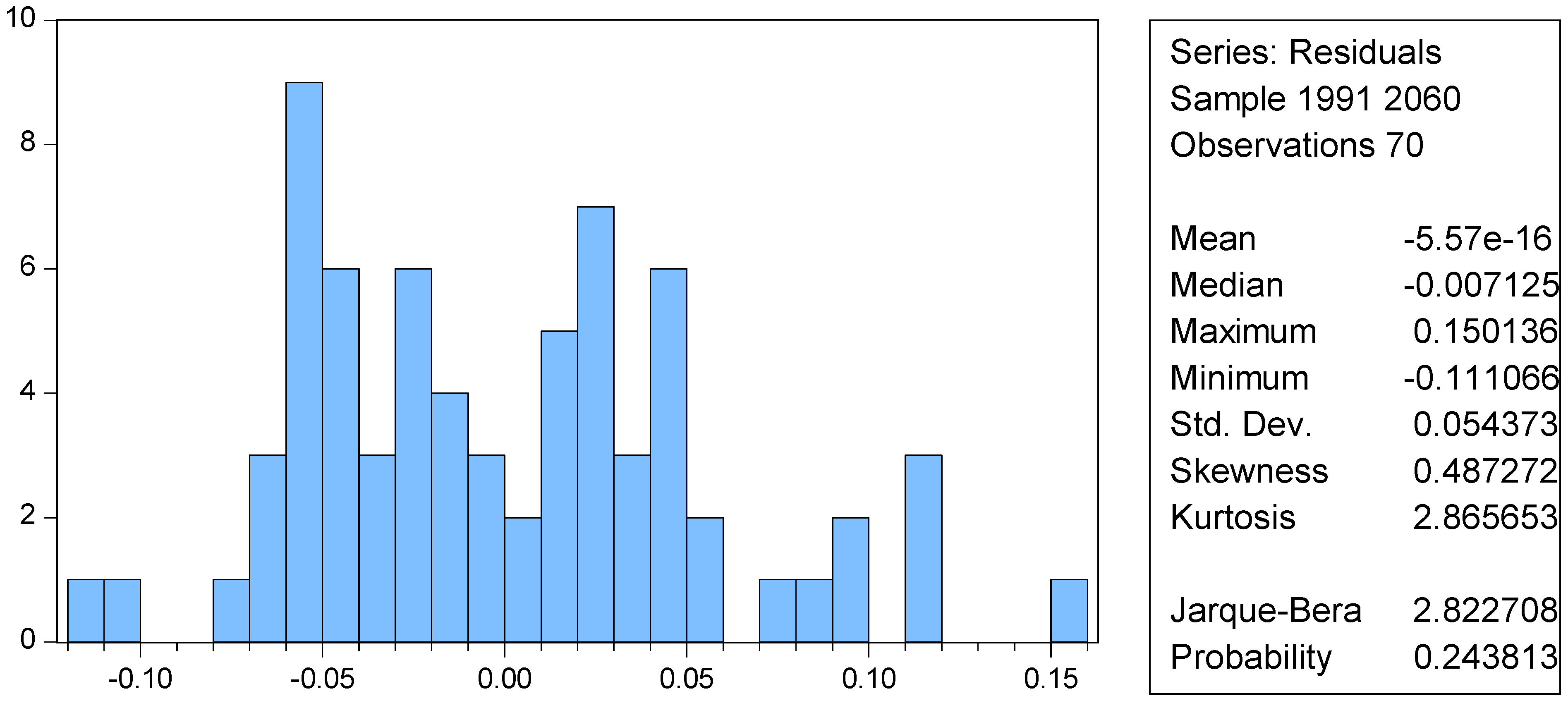

| Normality Test | Jarque–Bera | 2.822708 | Prob. | 0.243813 |

| Robust Least Squares Estimate | ||||

| Included Observations: 70 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Learner Academic Performance | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | z-Statistic | Prob. |

| AGE | 0.193731 | 0.127379 | 1.520906 | 0.1283 |

| EXPERIENCE SQUARED | −0.136903 | 0.055573 | −2.463492 | 0.0138 |

| EXPERIENCE | 0.184297 | 0.107104 | 1.720726 | 0.0853 |

| QUALIFICATION | 0.240479 | 0.458094 | 0.524955 | 0.5996 |

| MALE = 0 | 1.096236 | 0.53755 | 2.039318 | 0.0414 |

| MALE = 1 | 1.103899 | 0.540444 | 2.042577 | 0.0411 |

| R-squared | 5.126931 | Rw-squared | 5.16527 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 4.058723 | Prob. | 0.0000 | |

| Normality Test | Jarque–Bera | 2.89868 | Prob. | 0.234725 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mpiti, V.S.; Ncanywa, T.; Asaleye, A.J. Do Educators’ Demographic Characteristics Drive Learner Academic Performance? Examining the Role of Gender, Qualifications, and Experience. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040487

Mpiti VS, Ncanywa T, Asaleye AJ. Do Educators’ Demographic Characteristics Drive Learner Academic Performance? Examining the Role of Gender, Qualifications, and Experience. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(4):487. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040487

Chicago/Turabian StyleMpiti, Vuyelwa Signoria, Thobeka Ncanywa, and Abiola John Asaleye. 2025. "Do Educators’ Demographic Characteristics Drive Learner Academic Performance? Examining the Role of Gender, Qualifications, and Experience" Education Sciences 15, no. 4: 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040487

APA StyleMpiti, V. S., Ncanywa, T., & Asaleye, A. J. (2025). Do Educators’ Demographic Characteristics Drive Learner Academic Performance? Examining the Role of Gender, Qualifications, and Experience. Education Sciences, 15(4), 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040487