Shame Regulation in Learning: A Double-Edged Sword

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Shame Regulation

2.1.1. Shame Regulation Prompts in the Present Study

2.1.2. Stages of Shame Regulation

2.2. Failure-Driven Learning Context

Shame Regulation and Learning

3. Method

3.1. Participants

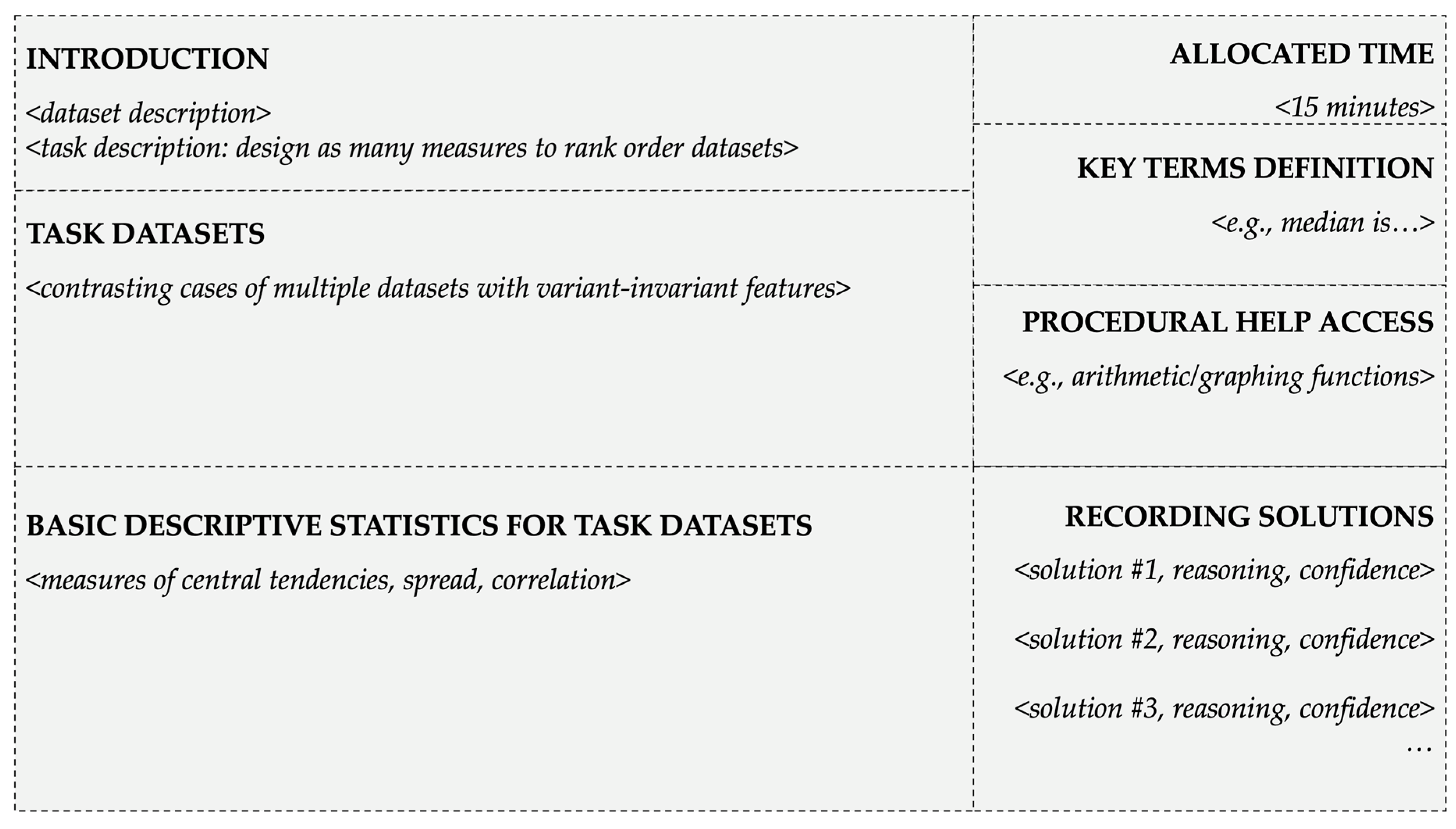

3.2. Learning Materials

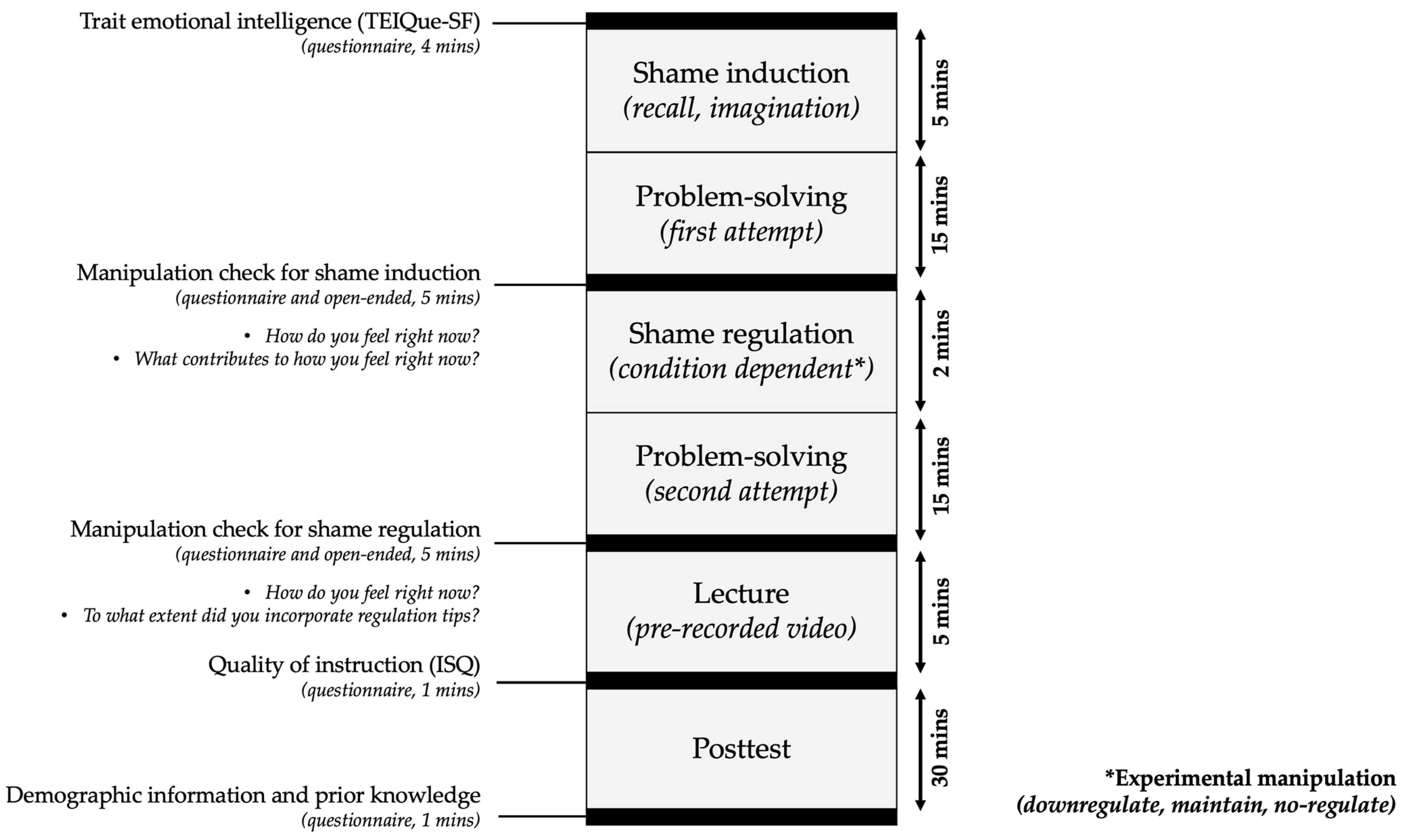

3.3. Study Design

3.4. Measures

3.4.1. Before the First Attempt of the Problem-Solving Phase

3.4.2. Before the Second Attempt of the Problem-Solving Phase

3.4.3. After the Second Attempt of the Problem-Solving Phase

3.4.4. After Instruction

3.4.5. After Post-Test

3.5. Analysis Plan

3.5.1. Facial Expression Data

3.5.2. Qualitative Data Coding

3.6. Hypotheses

- RQ1 (learning): How does emotion regulation impact learning in the post-test?

- H1a (accuracy): With respect to the accuracy of the post-test solutions (percentage aligning with the canonical answer), participants in the maintain condition will score (i) lower on the isomorphic conceptual understanding question, (ii) similar on the non-isomorphic conceptual understanding question, and (iii) higher on transfer questions, relative to the downregulate and no-regulate conditions.

- H1b (reasoning quality): With respect to the reasoning quality of the solutions developed at the post-test, participants in the maintain condition will score consistently higher in the completeness, accuracy, and integration dimensions of reasoning across all three post-test questions (relative to the downregulate and no-regulate condition).

- RQ2 (shame regulation): How are different stages of emotion regulation (Table 3) distributed across the downregulate, maintain, and no-regulate conditions?

- H2a (identification stage): Fewer participants will identify shame and other unpleasurable emotions as damaging their self-image in the maintain condition relative to the downregulate and no-regulate conditions (SDdownregulate and SDno-regulate > SDmaintain).

- H2b (selection stage): For participants who find the regulation tips sensible across all conditions, a relatively lower proportion of them will also acknowledge the helpfulness of the tip in their current problem-solving (A2) compared to those who agree with the reasoning presented in the tip (A1), that is, A2 < A1. Conversely, for participants across all conditions who do not find the regulation tips sensible in the first place, a similar proportion will disagree with the tips’ reasoning and find them hard to use in their problem-solving attempts (D1–D2).

- H2c (implementation stage): Relative to the downregulate condition, a higher proportion of participants will deploy their attention toward problem-solving (AD1) by reinterpreting it with an approach orientation (R1) in the maintain condition. A reverse trend will hold with respect to the relatively maladaptive strategies of deploying attention away from problem-solving (AD2) and focusing too much on how problem-solving performance may damage participants’ self-image (R2).

- H2d (monitoring stage): A higher proportion of participants in the downregulate condition would achieve their intended regulation results compared to those in the maintain condition (IRdownregulate > IRmaintain). Conversely, a higher proportion of participants in the maintain condition would be unable to achieve their intended regulation results relative to the downregulate condition (NRmaintain > NRdownregulate).

4. Results

4.1. Fidelity of Shame Regulation

4.2. Learning (RQ1)

- ∘

- The downregulate and no-regulate conditions performed similarly (Cohen’s d = 0.10) in the simplest isomorphic conceptual understanding question focusing on univariate data, while both these conditions outperformed the maintain condition (Cohen’s d = 0.45 and 0.35, respectively). The BFc corresponding to this overall observed trend in marginal means (maintain < downregulate = no-regulate) was 14.36, indicating strong odds in favor of this informative hypothesis relative to its complement. In simple words, the Bayes factor of a specific descriptive hypothesis being tested versus its complement (BFc) was obtained by running a Bayesian informative hypotheses evaluation ANCOVA (Hoijtink et al., 2019), which directly quantified the strength of evidence or odds in favor of the hypothesis.

- ∘

- The relative differences between the three conditions drastically reduced for the non-isomorphic conceptual understanding question with relatively higher intrinsic cognitive load, with the maintain condition performing similarly relative to the downregulate (Cohen’s d = 0.11) and no-regulate (Cohen’s d = 0.12) conditions. The BFc corresponding to this overall observed trend in marginal means (maintain = downregulate = no-regulate) was 53.32, indicating very strong odds in favor of this informative null hypothesis relative to its complement.

- ∘

- Finally, as expected, trends completely reversed when looking at the transfer post-test question introducing novel ideas about hypothesis testing into reasoning with the problem and requiring the highest level of mental effort and processing—where the maintain condition outperformed both the downregulate (Cohen’s d = 0.13) and no-regulate (Cohen’s d = 0.28) conditions. The BFc corresponding to this overall observed trend in marginal means (maintain > downregulate = no-regulate) was 10.99, indicating strong odds in favor of this informative hypothesis relative to its complement.

- ∘

- The downregulate and no-regulate conditions performed similarly (Cohen’s d = 0.04) in the simplest isomorphic conceptual understanding question, but contrary to the trends in post-test scores, both these conditions were actually outperformed by the maintain condition (Cohen’s d = 0.25 and 0.28, respectively).

- ∘

- The maintain condition scored similarly to the no-regulate condition (Cohen’s d = 0.10) and further outperformed the downregulate condition (Cohen’s d = 0.18) in the non-isomorphic conceptual understanding question.

- ∘

- For the transfer question, the maintain condition was still superior to the downregulate condition (Cohen’s d = 0.33) and the no-regulate condition (Cohen’s d = 0.32).

4.3. Shame Regulation (RQ2)

5. Discussion

5.1. Learning (RQ1)

5.2. Shame Regulation (RQ2)

5.3. Implications for Theory and Practice

5.4. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barrett, L. F., Adolphs, R., Marsella, S., Martinez, A. M., & Pollak, S. D. (2019). Emotional expressions reconsidered: Challenges to inferring emotion from human facial movements. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 20(1), 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belland, B. R., Kim, C., & Hannafin, M. J. (2013). A framework for designing scaffolds that improve motivation and cognition. Educational Psychologist, 48(4), 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, M. T. H. (1997). Quantifying qualitative analyses of verbal data: A practical guide. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 6(3), 271–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A., & Petrides, K. V. (2010). A psychometric analysis of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire–Short Form (TEIQue–SF) using item response theory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(5), 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordaro, D. T., Sun, R., Keltner, D., Kamble, S., Huddar, N., & McNeil, G. (2018). Universals and cultural variations in 22 emotional expressions across five cultures. Emotion, 18(1), 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowen, A. S., Keltner, D., Schroff, F., Jou, B., Adam, H., & Prasad, G. (2021). Sixteen facial expressions occur in similar contexts worldwide. Nature, 589(7841), 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B. Q., & Gross, J. J. (2019). Why beliefs about emotion matter: An emotion-regulation perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(1), 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B. Q., & Mauss, I. B. (2014). The paradoxical effects of pursuing positive emotion: When and why wanting to feel happy backfires. In J. Gruber, & J. T. Moskowitz (Eds.), Positive emotion: Integrating the light sides and dark sides (pp. 363–381). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2(2), 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. M., & Schwartz, B. (2011). Too much of a good thing: The challenge and opportunity of the inverted U. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutentag, T., Halperin, E., Porat, R., Bigman, Y. E., & Tamir, M. (2017). Successful emotion regulation requires both conviction and skill: Beliefs about the controllability of emotions, reappraisal, and regulation success. Cognition and Emotion, 31(6), 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanushek, E. A. (2011). Valuing teachers: How much is a good teacher worth. Education Next, 11(3), 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, J. M., Lajoie, S. P., Frasson, C., & Hall, N. C. (2017). Developing emotion-aware, advanced learning technologies: A taxonomy of approaches and features. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 27, 268–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoijtink, H., Mulder, J., van Lissa, C., & Gu, X. (2019). A tutorial on testing hypotheses using the Bayes factor. Psychological Methods, 24(5), 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holbert, N. (2020). Constructionism as a pedagogy of disrespect. In N. Holbert, M. Berland, & Y. B. Kafai (Eds.), Designing constructionist futures: The art, theory, and practice of learning designs (pp. 141–149). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, D. L., Chan, M. Y., Heintzelman, S. J., Tay, L., Diener, E., & Scotney, V. S. (2020). The manipulation of affect: A meta-analysis of affect induction procedures. Psychological Bulletin, 146(4), 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalokerinos, E. K., Greenaway, K. H., Pedder, D. J., & Margetts, E. A. (2014). Don’t grin when you win: The social costs of positive emotion expression in performance situations. Emotion, 14(1), 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, M., & Bielaczyc, K. (2012). Designing for Productive Failure. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 21(1), 45–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C., & Pekrun, R. (2014). Emotions and Motivation in Learning and Performance. In J. Spector, M. Merrill, J. Elen, & M. Bishop (Eds.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knol, M. H., Dolan, C. V., Mellenbergh, G. J., & van der Maas, H. L. (2016). Measuring the quality of university lectures: Development and validation of the instructional skills questionnaire (ISQ). PLoS ONE, 11(2), e0149163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koole, S. L. (2009). The psychology of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Cognition and Emotion, 23(1), 4–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamnina, M., & Chase, C. C. (2019). Developing a thirst for knowledge: How uncertainty in the classroom influences curiosity, affect, learning, and transfer. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 59, 101785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, C. W., & Cidam, A. (2015). When is shame linked to constructive approach orientation? A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(6), 983–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lench, H. C., Reed, N. T., George, T., Kaiser, K. A., & North, S. G. (2024). Anger has benefits for attaining goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 126(4), 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loibl, K., Roll, I., & Rummel, N. (2017). Towards a theory of when and how problem solving followed by instruction supports learning. Educational Psychology Review, 29(4), 693–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauss, I. B., Tamir, M., Anderson, C. L., & Savino, N. S. (2011). Can seeking happiness make people unhappy? Paradoxical effects of valuing happiness. Emotion, 11(4), 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D. K., & Turner, J. C. (2007). Scaffolding emotions in classrooms. In P. A. Schutz, & R. Pekrun (Eds.), Emotion in education (pp. 243–258). Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naismith, L. M., & Lajoie, S. P. (2018). Motivation and emotion predict medical students’ attention to computer-based feedback. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 23, 465–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naragon-Gainey, K., McMahon, T. P., & Chacko, T. P. (2017). The structure of common emotion regulation strategies: A meta-analytic examination. Psychological Bulletin, 143(4), 384–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoidbach, J., Mikolajczak, M., & Gross, J. J. (2015). Positive interventions: An emotion regulation perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 141(3), 655–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosiek, J. (2003). Emotional scaffolding: An exploration of the teacher knowledge at the intersection of student emotion and the subject matter. Journal of Teacher Education, 54(5), 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4(3), 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, M. E. P. (1991). Learned optimism: How to change your mind and your life. Pocket Books. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, T. (2022). Enriching problem-solving followed by instruction with explanatory accounts of emotions. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 31(2), 151–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, T. (2025). Emotion regulation during failure-driven learning. In Proceedings of the 19th international conference of the learning sciences—ICLS 2025. International Society of the Learning Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, T., & Dhandhania, S. (2022). Democratizing emotion research in learning sciences. In International conference on artificial intelligence in education (pp. 156–162). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, T., & Kapur, M. (2021a). Robust effects of the efficacy of explicit failure-driven scaffolding in problem-solving prior to instruction: A replication and extension. Learning and Instruction, 75, 101488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, T., & Kapur, M. (2021b). When problem solving followed by instruction works: Evidence for productive failure. Review of Educational Research, 91(5), 761–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, T., Kapur, M., West, R., Catasta, M., Hauswirth, M., & Trninic, D. (2021). Differential benefits of explicit failure-driven and success-driven scaffolding in problem-solving prior to instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(3), 530–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, M. (2016). Why do people regulate their emotions? A taxonomy of motives in emotion regulation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 20(3), 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, M., Bigman, Y. E., Rhodes, E., Salerno, J., & Schreier, J. (2015). An expectancy-value model of emotion regulation: Implications for motivation, emotional experience, and decision making. Emotion, 15(1), 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J. P., & Tracy, J. L. (2012). Self-conscious emotions. In M. R. Leary, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 446–478). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2006). Appraisal Antecedents of Shame and Guilt: Support for a Theoretical Model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(10), 1339–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, J., Kaszycki, A., Geden, M., & Bunde, J. (2020). Some stress is good stress: The challenge-hindrance framework, academic self-efficacy, and academic outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(8), 1632–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J. E., & Schallert, D. L. (2001). Expectancy–value relationships of shame reactions and shame resiliency. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(2), 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R. J., Chichekian, T., Verner-Filion, J., & Bélanger, J. J. (2023). The two faces of persistence: How harmonious and obsessive passion shape goal pursuit. Motivation Science, 9(3), 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Sinha, T., & Kapur, M. (2024). Which bright side to look at? Cultivating goal-oriented shame regulation under challenging problem-solving contexts. In Proceedings of the 18th international conference of the learning sciences—ICLS 2024 (pp. 226–233). International Society of the Learning Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidman, A. C., & Kross, E. (2021). Examining emotional tool use in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(5), 1344–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willroth, E. C., Young, G., Tamir, M., & Mauss, I. B. (2023). Judging emotions as good or bad: Individual differences and associations with psychological health. Emotion, 23(7), 1876–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Condition | Prompt |

|---|---|

| Downregulate | When other students in the past have attempted this task and encountered difficulties, they also felt shame. However, they did not dwell too much on it and instead felt happy that they were at least getting paid for the study. TIP: So, you may also try to avoid acknowledging that you may be feeling shame and always put a positive spin on your experiences. You now have another opportunity to re-attempt the task and practice this tip. Please go ahead and revise your solutions. |

| Maintain | When other students in the past have attempted this task and encountered difficulties, they also felt shame. However, they found shame to be useful because this led them to self-reflection and approach the task with even more focused efforts to restore their self-image. TIP: So, you may try to cultivate and experience shame in pursuit of your task goals and not assume the worst. You now have another opportunity to re-attempt the task and practice this tip. Please go ahead and revise your solutions. |

| No-regulate | You now have another opportunity to re-attempt the task. Please go ahead and revise your solutions. |

| Level 1—Reasoning completeness | |||

| Name | General definition | Label | Examples from the data |

| Presentation (κ = 0.77) | Participants presented or computed numerical or graphical representations. | P | Calculating the variance of a dataset, Drawing a scatterplot or histogram |

| Elaboration (κ = 0.97) | Participants described the mathematical meaning and trends in the data evident from drawing the numerical or graphical representations in isolation. | E | “The index histogram is almost symmetric” “One dataset has larger variance in account balance which means it is not stable” |

| Connection (κ = 0.90) | Participants explicitly connected the trends in the data with the problem-solving task. | C | “Dataset B has rounded values for the TimeSinceFirstAccount attribute, which leads me to think that they were aggregated into bins to anonymise them.” “The skewness information represents that air quality index might be distributed symmetrically” |

| Justification (κ = 0.73) | Participants supported the connection between their solutions and the problem-solving task with reasons for why the data trends can serve as plausible evidence. | J | “It is unnatural for data points with both lower TimeSinceFirstAccount and lower AccountBalance to have darker color (higher CreditScore)” “The wealth owned by the community means that the middle class should be large, which is supported by the small variance of the wealth because the distribution is more concentrated” |

| Level 2—Reasoning accuracy | |||

| Name | General definition | Label | Examples from the data |

| Graphical accuracy (κ = 0.95) | Participants were accurate in their connection or justification for the graphical representations used/generated (cf. level 1). | GA | “The graph distribution represents the assumption that the data is approximately distributed in a normal way” |

| Numerical accuracy (κ = 0.89) | Participants were accurate in their connection or justification for the numerical representations used/generated (cf. level 1). | NA | “If I understand the mayor’s ideology correctly, he wants wealth to be distributed as equally as possible. Since A has the lowest standard deviation, it should be the most representative scenario for the mayor’s ideology. According to the same criteria, scenario C is ranked second best and scenario B third best” |

| Level 3—Reasoning integration | |||

| Name | General definition | Label | Examples from the data |

| Graphical and numerical aggregation (κ = 1) | Participants combined both numerical and graphical representations that they used/generated in the final reasoning for the problem-solving task. | GN | “The credit score is predicted by calculation the linear regression using the time since first account and the account balance. A higher account balance and longer time since opening an account should lead to a higher credit score, which is only clearly the case in dataset B. I chose to construct the graphs as I did because of the tutorial for adding a third variable and because of the regression equation, showing that the credit score is dependent on the other two variables.” “p-value of 0.03 is less than alpha of 0.05, which indicates rejection of H0, hence not a normal distribution. Skewness of air quality 0.0 indicates equal distribution in the right tail of the distribution and in the left tail of the distribution. By plotting the dots into bar groups, the graph shows a distribution very close to normal distribution. Combining the evidence above, it is ok to conclude that the air quality index scores across the cities are approximately normally distributed” |

| Level 1—Identification | |||

| Name | General definition | Label | Examples from the data |

| Self-image damage-related emotions (κ = 0.67) | Participants explicitly stated negative feelings about themselves during the problem-solving. | SD | “While doing the first attempt, I felt a bit helpless and stupid” |

| No self-image damage-related emotions (κ = 0.80) | Participants explicitly stated non-negative (neutral/positive) feelings about themselves during the problem-solving. | ND | “I did not feel a fair amount of shame” |

| Level 2—Selection | |||

| Name | General definition | Label | Examples from the data |

| Agree with tip (tip_sensible = yes) (κavg = 0.68) | Participants acknowledged or agreed with the reasoning for the regulation strategy presented in the tip (κ = 0.53) | A1 | “I think it is important to see things in a positive way even if they are not going so well” “Being reminded of how this is just a study, and not an exam that evaluates my abilities made me less stressed and happy that I’m getting money after this experiment” |

| Participants found the information provided in the tip helpful for actually using it in their problem-solving task (κ = 0.84) | A2 | “I felt better since I knew that I was a beginner with this tool and I needed guidance to kickoff from where I am” “Knowing that other people may feel the same made me feel better. I shouldn’t think how the others are solving the problem in a better or worst way.” | |

| Disagree with tip (tip_sensible = no) (κavg = 0.82) | Participants did not acknowledge or agree with the reasoning for the regulation strategy presented in the tip (κ = 0.84) | D1 | “How other people performed does not change the fact that I performed badly” |

| Participants found the regulation strategy presented in the tip hard to achieve/use in their problem-solving task (κ = 0.71). | D2 | “I found it hard to acknowledge the positive aspect in the fact that I’m getting paid for the study. The negative feeling due to the unclear exercise was too strong …” “I didn’t quite understand how i should use my shame to achieve more satisfying results” | |

| Participants found the tip not applicable to them (e.g., because they did not feel shame) (κ = 0.92) | D3 | “…they also felt shame.” But I actually don’t. So it doesn’t really apply to me. I am actually happy to…” | |

| Level 3—Implementation | |||

| Name | General definition | Label | Examples from the data |

| Attentional deployment as an emotion regulation strategy (κavg = 0.78) | Participants deployed their attention toward problem-solving (e.g., intentionally accepting the triggered emotions to focus on the task) (κ = 0.80) | AD1 | “I gave myself time to complete the task without stressing out about it” “I just thought about doing my best without worrying too much about whether i am right or wrong” “I tried to be open-minded and think in new directions” “I do not know how to incorporate the tip into the assessment other than to remind myself that it is ok to be frustrated” |

| Participants deployed their attention away from problem-solving (e.g., toward other positive aspects of the situation) (κ = 0.76) | AD2 | “I acknowledge the positive aspect in the fact that I’m getting paid for the study” | |

| Re-appraisal as an emotion regulation strategy (κavg = 0.63) | Participants tried to change the way they interpreted the problem-solving situation (κ = 0.63). | R1 | “This is an open question without standard answers, so try without hesitation” “I struggled with knowledge rather than with execution or something else” “I focused on providing a better solution and perceived this as a challenge” |

| Participants tried to change the way they interpret the influence of the problem-solving experience on their self-image (κ = 0.63). | R2 | “Knowing that other people may feel the same made me feel better” “This also leads to a feeling of fulfillment even if the task did not turn out as though because I know I gave and did my best” “I don’t see the point being ashamed of something you have not done and tried before such as this case study” | |

| Level 4—Monitoring | |||

| Name | General definition | Label | Examples from the data |

| Ideal results | Participants explicitly reported a change in their emotions that was in accordance with their regulation efforts (κ = 0.90). | IR | “Knowing that other people may feel the same made me feel better” “Being reminded of how this is just a study, and not an exam that evaluates my abilities made me less stressed and happy that I’m getting money after this experiment.” |

| Non-ideal results | Participants explicitly reported attempting to regulate their emotions and did not achieve the intended outcomes (κ = 0.48). | NR | “The negative feeling due to the unclear exercise was too strong and I did not find the ideas very helpful either” “However it turns out I could not manage the emotions well” |

| Self-Reports (Min 1, Max 5) (Questionnaires) | Incidence (Min 0%, Max 100%) (Facial Expressions) | Betweenness Centrality (Min 0, Max 1) (Facial Expressions Network) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First problem-solving attempt (before experimental manipulation) | ||||

| Shame | 2.83 (1.38) | 35.51 (28.37) | 0.09 | |

| Happiness | 1.98 (1.01) | 1.35 (3.35) | 0.01 | |

| Satisfaction | 1.91 (1.04) | - | - | |

| Anger | 2.08 (1.18) | 23.54 (24.33) | 0.06 | |

| Contempt | 2.06 (0.98) | 12.40 (14.14) | 0.03 | |

| Disgust | 1.77 (1.02) | 0.12 (0.55) | 0.01 | |

| Pride | 1.73 (0.89) | 17.04 (23.05) | 0.05 | |

| Boredom | 2.46 (1.17) | - | - | |

| Sadness | 2.40 (1.29) | - | - | |

| Fear | 1.93 (1.11) | 4.53 (7.88) | 0.01 | |

| Amusement | - | 1.35 (3.35) | 0.02 | |

| Awe | - | 1.18 (2.43) | 0.02 | |

| Surprise | - | 29.97 (28.56) | 0.05 | |

| Confusion | - | 23.54 (24.33) | 0.06 | |

| Embarrassment | - | 2.84 (7.67) | 0.01 | |

| Pain | - | 0.41 (1.16) | 0.00 | |

| Second problem-solving attempt (after experimental manipulation) | ||||

| Shame | Maintain | 2.70 (1.32) | 30.05 (29.62) | 0.03 |

| Downregulate | 2.39 (1.40) | 33.17 (32.14) | 0.01 | |

| No-regulate | 2.89 (1.30) | 29.15 (28.85) | 0 | |

| Happiness | Maintain | 1.98 (1.07) | 1.69 (5.52) | 0 |

| Downregulate | 2.34 (1.03) | 1.48 (4.86) | 0.06 | |

| No-regulate | 2.11 (1.04) | 1.65 (7.33) | 0.04 | |

| Satisfaction | Maintain | 2.02 (1.17) | - | - |

| Downregulate | 2.41 (1.21) | |||

| No-regulate | 1.91 (1.14) | |||

| Anger | Maintain | 2.02 (1.30) | 26.05 (28.97) | 0.06 |

| Downregulate | 1.50 (0.73) | 22.10 (26.71) | 0.04 | |

| No-regulate | 2.18 (1.33) | 20.65 (23.48) | 0.07 | |

| Contempt | Maintain | 2.04 (0.96) | 6.66 (9.90) | 0.01 |

| Downregulate | 1.89 (0.97) | 9.83 (15.31) | 0.13 | |

| No-regulate | 2.23 (1.18) | 8.57 (16.03) | 0.01 | |

| Disgust | Maintain | 1.80 (1.10) | 0.16 (0.89) | 0 |

| Downregulate | 1.41 (0.69) | 0.14 (0.46) | 0.01 | |

| No-regulate | 1.93 (1.13) | 0.44 (2.78) | 0 | |

| Pride | Maintain | 1.75 (1.04) | 20.36 (29.24) | 0.08 |

| Downregulate | 2.00 (1.01) | 22.21 (29.48) | 0.06 | |

| No-regulate | 1.80 (0.95) | 14.21 (23.43) | 0.07 | |

| Boredom | Maintain | 2.54 (1.17) | - | - |

| Downregulate | 2.45 (1.28) | |||

| No-regulate | 2.86 (1.27) | |||

| Sadness | Maintain | 2.07 (1.17) | - | - |

| Downregulate | 1.68 (1.05) | |||

| No-regulate | 2.43 (1.30) | |||

| Fear | Maintain | 1.68 (1.03) | 3.54 (6.93) | 0.01 |

| Downregulate | 1.39 (0.87) | 6.09 (13.83) | 0 | |

| No-regulate | 1.93 (1.06) | 4.58 (10.04) | 0 | |

| Amusement | Maintain | - | 1.69 (5.52) | 0 |

| Downregulate | 1.48 (4.86) | 0.07 | ||

| No-regulate | 1.65 (7.33) | 0.25 | ||

| Awe | Maintain | - | 1.23 (3.32) | 0 |

| Downregulate | 1.36 (3.33) | 0 | ||

| No-regulate | 1.09 (4.30) | 0 | ||

| Surprise | Maintain | - | 30.43 (32.62) | 0.15 |

| Downregulate | 30.37 (34.01) | 0 | ||

| No-regulate | 36.35 (35.95) | 0 | ||

| Confusion | Maintain | - | 26.05 (28.97) | 0.06 |

| Downregulate | 22.10 (26.71) | 0.03 | ||

| No-regulate | 20.65 (23.48) | 0.07 | ||

| Embarrassment | Maintain | - | 3.35 (9.57) | 0.01 |

| Downregulate | 2.44 (6.33) | 0.02 | ||

| No-regulate | 2.37 (7.80) | 0.03 | ||

| Pain | Maintain | - | 0.38 (0.97) | 0 |

| Downregulate | 0.45 (1.54) | 0 | ||

| No-regulate | 0.61 (2.98) | 0.01 | ||

| Isomorphic Conceptual Understanding | Non-Isomorphic Conceptual Understanding | Transfer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-test accuracy (percentage correct) (min 0, max 1) | |||

| Maintain | 0.62 (0.06) | 0.46 (0.08) | 0.66 (0.08) |

| Downregulate | 0.81 (0.07) | 0.51 (0.08) | 0.59 (0.08) |

| No-regulate | 0.77 (0.06) | 0.52 (0.08) | 0.52 (0.08) |

| Post-test reasoning quality (completeness) (min 0, max 1) | |||

| Maintain | 0.64 (0.04) | 0.55 (0.04) | 0.89 (0.08) |

| Downregulate | 0.58 (0.04) | 0.50 (0.04) | 0.72 (0.08) |

| No-regulate | 0.57 (0.04) | 0.58 (0.04) | 0.72 (0.08) |

| Post-test reasoning quality (accuracy) (min 0, max 1) | |||

| Maintain | 0.22 (0.04) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.13 (0.04) |

| Downregulate | 0.23 (0.04) | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.07 (0.04) |

| No-regulate | 0.21 (0.04) | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.10 (0.04) |

| Post-test reasoning quality (integration) (min 0, max 1) | |||

| Maintain | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.43 (0.07) |

| Downregulate | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.34 (0.07) |

| No-regulate | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.03) | 0.36 (0.07) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sinha, T.; Wang, F.; Kapur, M. Shame Regulation in Learning: A Double-Edged Sword. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040502

Sinha T, Wang F, Kapur M. Shame Regulation in Learning: A Double-Edged Sword. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(4):502. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040502

Chicago/Turabian StyleSinha, Tanmay, Fan Wang, and Manu Kapur. 2025. "Shame Regulation in Learning: A Double-Edged Sword" Education Sciences 15, no. 4: 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040502

APA StyleSinha, T., Wang, F., & Kapur, M. (2025). Shame Regulation in Learning: A Double-Edged Sword. Education Sciences, 15(4), 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040502