Abstract

Relationships are central to the work of school leaders; however, little is currently known about how leadership preparation programs provide learning experiences for students which develop their relational abilities and orient them to adopt a relational stance in their work. The purpose of this paper is to fill this knowledge void by describing leadership preparation experiences provided through the IMPACT program. Specifically, we describe the IMPACT program and present the unique program features which exemplify how leadership preparation programs can create meaningful learning opportunities to achieve the following: (a) equipping students with the knowledge and skills needed to foster transformative relationships within their school communities; (b) nurturing students’ holistic development and well-being. Program features include university–school–community partnerships, student recruitment and selection, cohort model, leadership seminars, the curriculum and pedagogy, internship experiences, student mentoring and coaching, and post-graduation support. We use the literature on caring, compassionate school leadership, leader preparation, and mentorship to frame our discussion. Finally, we offer recommendations which enable leadership preparation programs to capitalize on the power of relationships in leaders’ development and, more broadly, school improvement processes.

1. Introduction

School leaders are called to cultivate caring, compassionate relationships within their school communities (Anderson et al., 2020; Hayes & Anderson, 2024; Lasater & LaVenia, 2024; Smylie et al., 2020). These types of relationships support student and teacher well-being, and they create school conditions which enable all members of the school community to flourish (Cherkowski & Walker, 2018). But cultivating caring, compassionate relationships in schools is neither easy nor intuitive. Rather, it requires leaders to utilize a variety of highly sophisticated intra- and interpersonal skills, such as active listening, emotional attunement, and reflexivity (Lasater, 2016; LaVenia et al., 2024). It also requires leaders to have competencies in managing the affective demands of the job and establishing school environments that are guided by an ethos of relational care and compassion for others.

Unfortunately, school reform efforts in the United States have created additional barriers to relationship development by prioritizing standardization, performance metrics, bureaucracy, and accountability over the humanistic aspects of schooling (Maxcy & Nguyễn, in press). These high-stakes, high-pressure reforms can steer leaders away from people and toward a dehumanized hyperfocus on student achievement data, student deficits, and school accountability measures (Lasater et al., 2021a). This type of environment makes it even more difficult for leaders to create the ethos of relational care and compassion needed for school flourishing (Cherkowski & Walker, 2018; Smylie et al., 2020).

Problematically, aspiring leaders are rarely provided with the types of learning experiences needed to practice and refine these intra- and interpersonal skills, nor are they provided explicit learning opportunities which build their emotional competencies, nourish their personal well-being, and reorient them toward the humanistic aspects of schooling. In fact, despite the centrality of relationships in leaders’ work, relationship development is seldom prioritized in leadership preparation programs (Duncan et al., 2011; Epstein, 2011; LaVenia et al., 2024). This results in leaders entering the field without the training, skills, or developmental experiences needed to navigate the complex relational aspects of their positions (Epstein & Sanders, 2006).

Leaders’ lack of preparation for relationship development is particularly problematic given that nearly every aspect of a leader’s work is relational (National Policy Board for Educational Administration, 2018). Even more, the relational aspects of the principalship contribute significantly to principal stress, burnout, and retention (DeMatthews et al., 2021; Friedman, 2002). Friedman (2002) investigated stressors contributing to principal burnout and found that relational issues with teachers and parents impacted burnout more than other work-related stressors, including workload. Similarly, leaders in Mahfouz (2020) reported that relationship-related stressors, such as managing personalities and unpredictable attitudes, depleted their emotional reserves and impacted their overall health and well-being; these leaders described encountering “overwhelming situations” with people which they felt “socially” and “emotionally unprepared” to address (p. 452). Relational challenges, such as distrust and lack of support from others, contribute to principal turnover and attrition (Heffernan et al., 2023; Richard, 2025). In fact, leaders around the world report experiencing such extreme relational stressors associated with their positions that they have decided to leave or are considering leaving the profession (Kidson et al., 2024; National Association of Secondary School Principals, 2022; Richard, 2025).

As such, we consider preparation and support for the relational aspects of the job essential to building and sustaining leadership capacity within schools. We also believe leadership preparation programs play a critical role in this process. Specifically, we see leadership preparation programs as ideally positioned to achieve the following: (a) providing aspiring leaders with the learning experiences necessary to practice and receive feedback on their relational skills; (b) fostering mentoring relationships which assist emerging leaders in confronting the challenges associated with the principalship while simultaneously fostering a sense of community and camaraderie within the work; (c) nurturing leaders’ well-being so that the work is fulfilling, rejuvenating, and, subsequently, sustainable.

1.1. Positive School Leadership and IMPACT

It was with these beliefs in mind that the IMPACT Arkansas Fellowship (IMPACT) was developed. IMPACT is an innovative leadership preparation program that was designed to build leadership capacity across Arkansas by leveraging the power of positive school leadership to nurture leaders’ development, well-being, and sustainability in the field. Positive school leadership is a values-driven approach to leadership that “considers leadership a function of human relationships, enacted largely through interpersonal interaction” (Smylie et al., 2020, p. 134). It is concerned with the moral and ethical aspects of leadership and emphasizes leaders’ character and virtues (Murphy & Seashore Louis, 2018; Smylie et al., 2020). Positive school leadership consists of four core dimensions—positive orientation, moral orientation, relational orientation, and spiritual stewardship orientation—with trust and context cutting across each orientation (Murphy & Seashore Louis, 2018). Positive orientation is asset-based; moral orientation is value- and virtue-based, transcendent, and spiritual; relational orientation is care-based, growth-based, and authentic; and spiritual stewardship orientation is spiritually-grounded and service-anchored (Murphy & Seashore Louis, 2018). Trust is considered an essential thread which weaves together each dimension of positive school leadership (Bryk & Schneider, 2002; Murphy & Seashore Louis, 2018), whereas context is conceptualized as a moderating condition upon which leaders must continuously adjust their behaviors (Murphy & Seashore Louis, 2018). IMPACT is guided by the four core dimensions of positive school leadership; however, for the purposes of this paper, we focus on learning experiences aligned with relational orientation. This is because leaders often struggle with the relational aspects of their work (DeMatthews et al., 2021; Friedman, 2002; Mahfouz, 2020), and this is an area where leadership preparation programs have historically fallen short (Duncan et al., 2011; Epstein, 2011; LaVenia et al., 2024).

Relationships can be conceptualized as human connection and intimacy with others (Hargreaves & Shirley, 2022), and they are vitally important to organizational outcomes. As Murphy and Seashore Louis (2018) state, “Authentic, relationship-based leadership promotes employee trust, a sense of organizational justice, and a willingness to contribute voice to promoting the collective good; each of these is important in itself, and a precursor to collective performance” (p. 37). The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate how IMPACT uses a two-pronged approach to relationship development across leaders’ pre-service, induction, and in-service experiences. The first prong involves explicit instruction on relational skills, compassion toward the self and others, and nurturing well-being. The second prong involves centering relationships in program structure and implementation, such as how university–school–community partnerships are created and maintained and the extensive mentoring and coaching students receive. This two-pronged approach builds fellows’ relational competency through intentionally crafted learning experiences and by modeling the value and feasibility of establishing learning environments which center care and compassion for others. It is worth noting that leaders must navigate varied relationships within their roles (e.g., with students, parents, teachers, staff, community members), and each of these relationships are uniquely navigated and negotiated based on the dyadic relationship between the leader and member (Murphy & Seashore Louis, 2018). However, the same underlying skills and competencies are used in each, and as such, we focus our discussion on leadership preparation experiences which develop these skills and competencies rather than role-specific relationships. Specifically, we describe the IMPACT program and present the unique program features which foster ongoing, meaningful relationships with aspiring and current school leaders. We also describe how these features support leaders’ development and sustainability in the field. We offer this paper in hopes that it may prompt program design considerations which foreground relationship development.

1.2. Positionality

As faculty in the Educational Leadership program at the University of Arkansas, we have been intimately involved in the design, inception, delivery, growth, and improvement of IMPACT. John is the creator and original PI of IMPACT and has been a professor of Educational Leadership at the University of Arkansas since 2007. He continues to take the lead role in generating funds to support the program, and he supervises the executive director and teaches IMPACT students. Kara regularly teaches in the IMPACT program; she teaches a course which focuses on leaders’ role in cultivating strong family–school–community relationships (see discussion in Section 3.5).

2. Examining the Relational Needs of Emerging School Leaders

Relationships are woven into nearly every aspect of school leadership. Each of the ten Professional Standards for Educational Leaders (National Policy Board for Educational Administration, 2015) requires the use of relational skills to facilitate student learning and school improvement, and many of the standards speak explicitly to leaders’ role in fostering collaborative, caring relationships within their school communities. Despite the prevalence of relationships in leaders’ work, they remain an aspect of the job that many leaders are ill-prepared to manage (Duncan et al., 2011; Epstein & Sanders, 2006; LaVenia et al., 2024). Novice principals, in particular, face relational challenges associated with evaluating the pedagogy of veteran teachers, mentoring for continuous instructional improvement, advocating up the chain with district leaders, and communicating school values and norms across a diverse community of parents and stakeholders. As such, it is important that leadership preparation programs carefully consider the relational needs of leaders and provide them with the learning experiences necessary to feel more efficacious with the relational demands of the job.

To help us understand how preparation programs might support aspiring school leaders in developing enhanced relational skills, we turn to the literature on caring and compassionate school leadership, leadership preparation, and mentorship. The literature on caring, compassionate school leadership offers explicit guidance on how leaders can demonstrate relational values in their work. The literature on leadership preparation provides guidance on the learning experiences aspiring leaders need to develop relational competencies. Finally, the literature on mentorship sheds light on how leaders’ relational growth and development can be supported across their career trajectories.

2.1. Cultivating Relationships Through Caring, Compassionate School Leadership

The need for leaders to (re)center compassion and care in their work has gained recent attention (Lasater & LaVenia, 2024; Smylie et al., 2020). Caring, compassionate school leadership involves benevolence toward others, taking actions to support and/or serve them, and creating a “culture of care” within schools (Hayes & Anderson, 2024, p. 119). It represents a way of “being in relationship with others” (Smylie et al., 2020, p. 17). To be a caring, compassionate school leader is to recognize the distress, suffering, and/or needs of others (i.e., noticing); feel empathy for these experiences (i.e., feeling); and take deliberate actions that aim to alleviate distress or suffering (i.e., responding; Frost et al., 2006). Importantly, it also involves establishing and fostering organizational conditions which enable collective noticing, feeling, and responding across all members of the organization (Kanov et al., 2004). In essence, caring, compassionate school leadership is not a simple matter of demonstrating care and compassion for others; it requires establishing environments where compassion and care are rooted in the culture and ethos of the school.

This type of leadership requires that leaders possess and utilize a range of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and organizational skills. At the intrapersonal level, leaders must be able to recognize their own emotions, thoughts, values, motives, and behaviors (Gilbert & Choden, 2014); regulate their emotions in healthy, prosocial ways (Smylie et al., 2020); remain cognitively, emotionally, physically, and spiritually engaged in the present moment (Murphy, 2016); routinely practice reflexivity (Ravitch & Carl, 2021; York-Barr et al., 2001); and practice compassion for self (Gilbert, 2013; Neff, 2011). This necessitates that leader preparation programs provide learning experiences which invite deep reflection, offer meaningful feedback, nurture students’ holistic development, create space for creativity and risk-taking, and attend to students’ vulnerabilities as they develop new ways of thinking and acting.

At the interpersonal level, compassionate school leaders must emotionally attune to the experiences of others, demonstrate a willingness to be authentically present in others’ experiences, and, subsequently, respond in ways which are personally meaningful to the individual (Frost et al., 2000). This process requires leaders to develop skills in attuning to others’ experiences, actively listening, and tolerating others’ distress (Frost et al., 2006). Within their preparation programs, aspiring school leaders need routine opportunities to practice and receive feedback on their interpersonal skills. Preparation programs should also offer support for leaders in managing the emotional and cognitive demands associated with interpersonal work.

Finally, leaders must create an “emotional ecology” (Frost et al., 2000, p. 25) in which compassion and care are “legitimized,” “propagated,” and “coordinated” throughout the organization (Kanov et al., 2004, p. 816). This requires establishing norms, practices, routines, systems, and policies which prompt organizational members to collectively notice, feel, and respond to the distress and pain of other organizational members (Dutton et al., 2002; Kanov et al., 2004). As such, leaders need to develop skills in practicing care and compassion, cultivating the relational capacities of other organizational members, and coordinating relational efforts across the organization (Frost et al., 2006).

Ultimately, we see the development of caring, compassionate school environments as critical to building leadership capacity and promoting educators’ sustainability in the field. When compassion and care are embedded within organizational culture, employees experience a sense of camaraderie, collective efficacy, and shared commitment within their work that is rejuvenating and sustaining (see Kanov et al., 2004; Shirley et al., 2020). They also feel more attached to their colleagues and organization (Dutton et al., 2002). Establishing a school culture of care, belonging, and compassion is especially important in low-income schools and communities where students, families, and community members are more likely to feel unwelcome, ostracized, devalued, and marginalized by school personnel (DeMatthews, 2018; Gorski, 2018; Olivos, 2012; Theoharis, 2009). Thus, leadership preparation programs should create opportunities for aspiring leaders which assist them in cultivating cultures of care and compassion that are responsive to the needs of their unique school communities.

2.2. Leadership Preparation

Leaders’ responsibility to create compassionate, caring relationships within their schools suggests leadership preparation programs should take an active role in designing learning experiences which achieve the following: (a) developing aspiring leaders’ relational skills; (b) equipping them to build the relational capacities of their staff; (c) teaching them to cultivate trusting, caring, and compassionate school cultures; (d) prompting them to nurture their own and others’ well-being; (e) modeling the value of caring relationships for students through program design and implementation. First, leadership preparation programs should provide aspiring leaders with academic and practice-based experiences which strengthen their intra- and interpersonal competencies (Cosner, 2010). To develop these competencies, aspiring leaders need opportunities to learn about and practice active listening, effective communication, rapport, emotional attunement, trust-building, perspective-taking, conflict resolution, and self-awareness (Lasater, 2016; LaVenia et al., 2024; Smylie et al., 2020; Tschannen-Moran, 2014). Several intellectual virtues are precursors to these skills and practices, and among them, IMPACT prioritizes intellectual humility throughout the program. Intellectual humility sits at the heart of openness to new ideas, perspective-taking, understanding the limits of one’s own ideas, and honoring the contributions of others (Pijanowski & Lasater, 2020). It is an essential disposition in the development of healthy, trusting relationships, as it enables leaders to remain open and responsive to the emotional experiences of students and families, which is essential for leaders serving in racially, ethnically, culturally, and socioeconomically diverse communities (Gorski, 2018; Wilson Cooper et al., 2010).

Pedagogical approaches to cultivate these skills can include reflective (e.g., journaling, reflective dialog; Cunningham et al., 2019) and practice-based approaches. Example prompts to guide critical reflection could include the following: How do others perceive my verbal and nonverbal communication? What implicit and explicit messages do I send others about their value? What are my greatest concerns about cultivating relationships within my school? How can I embrace vulnerability as a future school leader? Roleplay is a useful practice-based approach to relational skill development, particularly when paired with direct feedback and opportunities for self-reflection (Lasater, 2016). These experiences also help leaders build the relational capacities of their staff. As emerging leaders become more experienced and confident in their use of relational skills, they can create similar learning opportunities for teachers and other school personnel through on-site professional development. Further, they can build capacity for relationships by modeling care and compassion in their work and coaching teachers and other school personnel on relational practices (Smylie et al., 2020).

Leadership preparation programs can also provide explicit training for aspiring leaders on developing school cultures of trust, care, and compassion (Anast-May et al., 2011). An important aspect of culture development is establishing norms, practices, routines, structures, and policies which support the organization’s values and beliefs (Deal & Peterson, 2009); thus, leaders need authentic learning activities which allow them to interact and influence the cultural aspects of their schools (Anast-May et al., 2011; de Zulueta, 2016). As an example, aspiring leaders could establish a school culture committee and collaborate with the committee to improve the school’s culture (Cosner et al., 2018a), particularly in ways which strengthen relationships within the school community. As another example, aspiring leaders could engage with members of their school community to ensure that the school’s mission and vision are aligned with principles of caring, compassionate relationships (Smylie et al., 2020).

Relatedly, aspiring leaders need opportunities to develop the knowledge and skills necessary to cultivate organizational compassion within their schools. Organizational compassion “involves a set of social processes in which noticing, feeling, and responding to pain are shared among a set of organizational members” (Kanov et al., 2004, p. 816). Leaders influence these processes through the routines, practices, and structures they create (Frost et al., 2006; Kanov et al., 2004); if caring, compassionate relationships are to be central to the work of schools, then aspiring leaders must learn to facilitate collective noticing, feeling, and responding through the routines, practices, structures, and policies they establish (Frost et al., 2006; Kanov et al., 2004). Authentic learning activities which could support the development of organizational compassion could include the following: providing feedback to staff about their relational, compassion-based competencies (Dutton & Workman, 2011); initiating a communication system which alerts organizational members to others’ hardships (Kanov et al., 2004); co-designing a compassion-based training program for school personnel (Potvin et al., 2022); modeling the routine sharing of compassion narratives in staff meetings (Lasater, 2024); and designing intentional opportunities for student and staff interaction (Cosner, 2009; Worline & Dutton, 2021).

Leadership preparation programs also offer a unique opportunity to socialize aspiring leaders to prioritize personal health and well-being (Lasater et al., 2024). School leadership is a complex, demanding profession (Theoharis, 2009) and working to meet the demands of the job can leave leaders feeling depleted and unwell (Ray et al., 2020). Under these circumstances, leaders’ work is neither optimal nor sustainable (Mahfouz & Richardson, 2020). Preparation programs can help shift professional norms by incorporating wellness-related content into program design, course delivery, and student support systems. For example, preparation programs can attend to students’ well-being by connecting them with a network of supportive administrators. These types of networks provide opportunities for aspiring leaders to “share ideas, emotional support, encouragement, and assistance in problem solving” (Theoharis, 2009, p. 115). Preparation programs could also facilitate learning related to the practice of self-compassion. Self-compassion is “an emotionally positive self-attitude that should protect against the negative consequences of self-judgment, isolation, and rumination” (Neff, 2003, p. 85); as such, it offers a powerful mechanism to combat common barriers to leaders’ well-being. Ultimately, prioritizing leaders’ well-being in preparation programs exemplifies compassion and care for others. It also sends a strong message that, above all else, education is a human enterprise.

Finally, leadership preparation programs can support aspiring leaders in understanding how to cultivate relationships amid complex sociopolitical dynamics. For example, leaders working in low-socioeconomic-status schools and communities may experience relational challenges emanating from issues of mistrust and power. Students and families from low-socioeconomic-status and racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse backgrounds often experience schools as sites of institutionalized bias, discriminatory practices, deficit perspectives, and unequal opportunity (DeMatthews, 2018; Gorski, 2018; Lewis & Diamond, 2015)—all of which contribute to distrust and relational distancing. This distrust and relational distancing are further magnified by power imbalances which often privilege the voices of affluent students, families, and community members over those from historically marginalized backgrounds (Lewis & Diamond, 2015; McCarthy Foubert, 2023). Thus, as leaders enter the field, they must do so with the knowledge and skills necessary to rebuild trust and connection across racial, ethnic, linguistic, and socioeconomic differences. Preparation programs can support aspiring leaders in developing this knowledge and these skills by providing them with opportunities to engage in direct, authentic interaction with students and families from diverse backgrounds; this authentic interaction should decenter the perspectives of educators and schools and facilitate reciprocal learning between educators and diverse members of the school community (Wilson Cooper et al., 2010).

2.3. Mentorship for Leaders’ Development

Mentoring offers another opportunity for leadership preparation programs to support aspiring leaders’ preparation, development, and sustainability in the field (Rhodes, 2012). Mentorship builds leaders’ capacity to influence adult learning and development in their schools and, subsequently, to improve student learning outcomes (Hayes, 2019). Mentorship also offers the opportunity to nurture leaders’ intrapersonal growth and holistic well-being (Lasater et al., 2021b; Varney, 2009), and it could help prepare leaders for managing the relational components of their work.

Traditionally, the mentorship of school leaders occurs in three phases: during their formal preparation, early career experiences, and later career experiences (Rhodes, 2012). During leaders’ formal preparation, students often receive a form of co-mentorship in which they are mentored by a faculty member in their preparation program and a school leader within their internship placement sites. However, because mentorship is often conceptualized as existing within programmatic, organizational, and structural bounds (Briscoe, 2019), the mentoring relationship often ceases upon students’ completion of their degree. This leaves future leaders without the socialization experiences necessary to feel prepared for the principalship (Bush, 2018).

After graduating from their preparation programs, many future school leaders do not receive mentorship again until formally transitioning into their first leadership position. At this point, the quality of mentorship leaders receive varies dramatically, as many school districts lack the infrastructure and human capacity necessary to provide leaders with meaningful support and developmental opportunities (Rhodes, 2012). This results in mentorship experiences that are fragmented across leaders’ career trajectory and culminates in leaders stepping into complex, demanding positions without a continuous system of support at their disposal.

Mentorship can more meaningfully contribute to leaders’ development if it is intentionally maintained across career experiences (Briscoe, 2019), exposes leaders to mentors with diverse personal and professional experiences (Drago-Severson et al., 2013; Mullen et al., 2020; Sherman & Crum, 2009), offers leaders opportunities to collaboratively engage in a variety of professional activities (e.g., teacher observations, data meetings; Hayes, 2019), and reciprocally supports leaders’ holistic well-being and development (Lasater et al., 2021b; Varney, 2009). Currently, this type of integrated, multi-faceted approach to mentorship across leaders’ career trajectory is uncommon; thus, it is important for the field to consider how preparation and induction programs might provide future and current school leaders with the mentoring experiences necessary to foster individual development, build long-term systemic capacity, and cultivate school cultures of care and compassion.

2.4. Toward a Relational Approach to Leadership Development

The centrality of relationships in leaders’ work is routinely documented in the literature (Anderson et al., 2024; Cosner, 2009; Lasater, 2016; Theoharis, 2009); however, much less is known about how leadership preparation programs provide learning experiences for students which develop their relational abilities. Thus, we present the IMPACT program as an opportunity to consider how an integrated, multifaceted approach to relationship development across pre-service, induction, and in-service experiences might assist leaders in developing the relational skills needed to create compassionate, caring school environments which support well-being.

3. The IMPACT Arkansas Fellowship

The IMPACT Arkansas Fellowship Program is a selective, scholarship-based preparation program designed to increase leadership capacity within low-income Arkansas schools by providing aspiring leaders with high-quality learning experiences which center relationships, nurture well-being, and promote flourishing in schools. IMPACT provides fellows with the opportunity to earn their master’s degree in educational leadership from the University of Arkansas. Once admitted to the program, fellows commit to staying in their schools for two years post-graduation.

Since its inception in 2014, IMPACT has recruited 168 aspiring school leaders (i.e., IMPACT fellows) across nine cohorts. The racial composition of fellows is 73% white, 22% African American, and 5% other. Fellows represent 145 high-poverty schools in 97 Arkansas public school districts and 8 charter schools, with recruitment currently underway for the 10th cohort. IMPACT fellows serve in high-poverty schools located in both rural and urban environments across Arkansas. The demographic makeup of these schools varies dramatically by geographic location. Some schools are racially and linguistically homogenous, while others are racially, culturally, and linguistically diverse. Interestingly, many fellows grew up in the schools and communities where they now work. The program follows a cohort model and includes 18 months of coursework taught by the University of Arkansas’s Educational Leadership faculty. All coursework is completed online through synchronous class sessions supplemented by asynchronous learning activities (e.g., discussion board, Voice Thread).

IMPACT was designed to build leadership capacity in high-poverty schools across Arkansas. Underscoring this purpose was the belief that building sustainable school leadership capacity would only be possible if caring, trusting, and supportive relationships were prioritized in all aspects of program design. To this end, multiple program features exemplify how leadership preparation programs can create meaningful learning opportunities which achieve the following: (a) equipping students with the intra- and interpersonal skills needed to build trusting relationships in their schools; (b) developing students’ competency in managing the affective demands of the job; (c) modeling for students the power of relationships in creating healthy, productive learning environments which are guided by an ethos of care and compassion for others; (d) attending to and nurturing students’ holistic development and well-being. Program features include university–school–community partnerships, student recruitment and selection, cohort model, leadership seminars, the curriculum and pedagogy, internship experiences, student mentoring and coaching, and post-graduation support. Importantly, these program features are consistent with principles of adult learning which emphasize embedding learning in relevant practice; intentional succession planning from within the organization; diverse and rigorous internship experiences; mentoring support from coaches, on-site supervisors, faculty, and cohort peers; ongoing opportunities to engage in reflective practice; and leadership development that extends into the early years of practice (Drago-Severson, 2009; Drago-Severson et al., 2013; Rhodes, 2012; Sherman & Crum, 2009; York-Barr et al., 2001). In the following sections, we describe these program features and the ways in which they support fellows’ relational competencies and/or cultivate a relational ethos within the program that nurtures the fellows’ well-being.

3.1. University–School–Community Partnerships

IMPACT involves partnerships between the university’s Educational Leadership Program, IMPACT staff, Arkansas school districts, and other community-based agencies. These partnerships are critical to designing learning experiences for fellows that are contextually relevant and personally meaningful, and they help establish school cultures which authentically welcome, engage, and honor students, families, and community members from diverse racial, ethnic, linguistic, and socioeconomic backgrounds (Allen, 2007). The University of Arkansas Educational Leadership faculty are responsible for teaching courses, securing funds to sustain and advance the program, and providing university-based mentorship for students. IMPACT staff, which consist of four full-time personnel, are responsible for student recruitment, establishing district partners, coaching and mentoring students, and managing the daily operations of the program. Community partners work with fellows on course assignments and internship activities to situate learning within their local contexts. Finally, district partners identify emerging leaders in their schools, provide on-site mentoring to fellows, and collaborate with fellows to design, execute, and evaluate continuous improvement efforts situated within their school contexts. Importantly, all IMPACT partners are committed to the shared goals of supporting fellows’ development and building leadership capacity across the state, and they collaboratively guide efforts to continuously grow and improve the program. Partners also work together to ensure that fellows are cared for and supported as they learn to balance the complex demands of leadership; this is considered important in nourishing fellows’ well-being and ensuring that they have an established support system which can help them overcome leadership challenges they encounter.

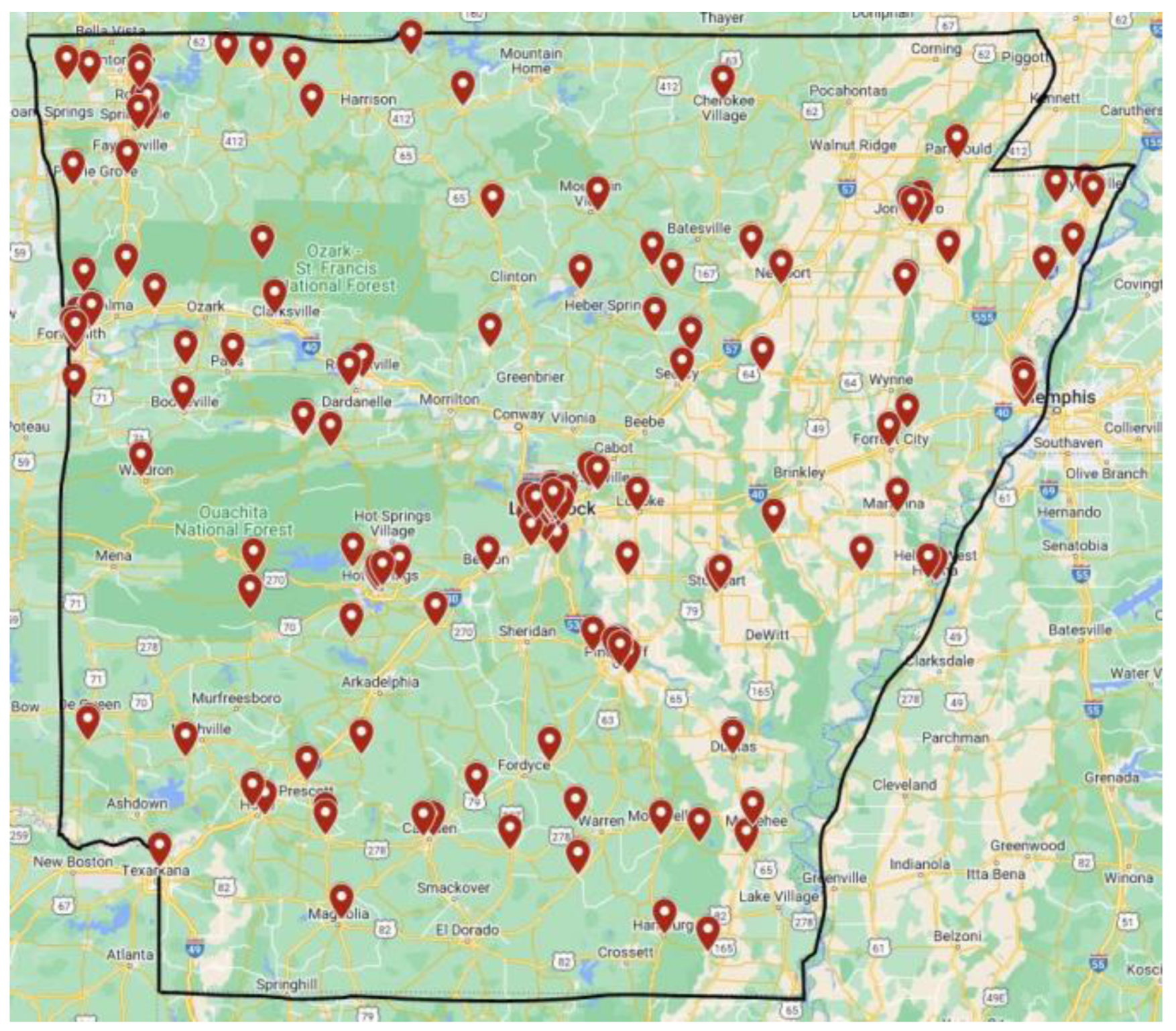

Since 2014, the program has developed partnerships with nearly two-thirds of high-poverty Arkansas school districts across every geographic region of the state (see Figure 1). Not only has IMPACT’s geographic reach and number of partner districts increased over time but so has the depth of partner engagement; now, ongoing knowledge sharing, problem-solving, and student support are routine, deliberate, and collaborative processes among IMPACT partners. Additionally, IMPACT fellows collaborate with members of their school community to develop service programs which meet students’ needs within the financial constraints they face. These partnerships allow fellows to make meaningful connections between theoretical concepts learned in courses, the authentic practice of school leaders, and the contextual and situational needs of their local schools and communities (Osworth et al., 2023). Furthermore, we believe IMPACT partnerships provide a valuable opportunity to demonstrate for fellows how trusting, collaborative, and caring relationships can be leveraged to build leadership capacity and guide school improvement efforts.

Figure 1.

IMPACT fellows’ locations in Arkansas.

3.2. Student Recruitment and Selection

IMPACT is a “grow-your-own” program. To be eligible for the fellowship, prospective students must have at least three years of teaching experience, and they must work in an Arkansas school where 70% or more of the student population qualifies for free or reduced-price lunch. To receive the fellowship, IMPACT fellows commit to staying in their district for at least two years post-graduation to support the program’s goals of developing leadership capacity and retention in high-poverty districts. Selection for IMPACT involves a rigorous, four-phase process. In Phase I, students submit a letter of recommendation from their school leader and evidence of their teaching effectiveness. As a result, student recruitment is an intentional process based on students’ proven abilities in their current school context and demonstrated potential around leading instruction, capacity building, collaboration with peers, and connection with the community. In Phase II, a phone interview and observation debrief are conducted with IMPACT staff. Phase III involves site visits to applicants’ schools and interviews with their administrators. Finally, in Phase IV, finalists are invited to participate in a culminating interview with the selection committee. This interview consists of a group problem-solving exercise, a group interview, and an individual interview. Following the interview, applicants receive feedback on their interactions with others, approach to problem-solving, and ability to collaboratively move the team toward productive action planning.

This multi-stage recruitment and selection process provides rich insights related to candidates’ leadership abilities, as well as their ability to connect with and relate to other people. It also facilitates intentional succession planning within the organization, strengthens the school’s leadership capacity, signals administrative support for fellow development, and creates opportunities for sustained support among IMPACT partners. Finally, this process provides early socialization experiences that orient fellows to the collaborative nature of the program and helps establish norms of vulnerability, trust, support, intellectual humility, and high expectations.

3.3. Cohort Model

IMPACT uses a cohort model of leadership development. This approach capitalizes on the social, relational aspects of learning which are central to IMPACT’s vision. Specifically, cohorts provide opportunities for collective reflection (Osworth et al., 2023), collaboration and interdependent work (Cunningham et al., 2019), and relationship-building between peers (Anderson et al., 2018). Social learning is such an integral part of IMPACT training that prospective students begin collaborating with their peers before they are even admitted to the program. During Phase IV of the interview process, candidates work in small groups to roleplay a leadership team working together to address a complex problem situated within their local school context while the IMPACT team plays the state department of education. This experience creates immediate opportunities for fellows to engage in collective risk-taking and problem-solving. Following the roleplay exercise, the IMPACT team provides feedback specific to candidates’ interactions within the group. These types of interdependent, social learning experiences continue throughout fellows’ programs of study.

Fellows are also encouraged by IMPACT staff to create a peer network of communication and support. Fellows use GroupMe to communicate about coursework, share ideas related to school-based activities, and support each other during times of personal struggle or need (e.g., family illness). They also establish smaller groups within GroupMe that allow for more specialized collaboration based on geographic region, shared interests, and/or developmental needs. This social network is invaluable in supporting fellows’ well-being as they complete coursework and transition into the principalship.

3.4. Leadership Seminar

Fellows participate in a leadership seminar which provides a hands-on, data-driven approach to addressing educational challenges and improving student outcomes. The seminar series consists of in-person symposiums and a combination of virtual and in-person meetings designed to empower leaders, promote flexibility and relevance to high-poverty schools, foster collaboration, and support continuous improvement. The in-person experiences bring fellows together with various leadership experts and program staff from across Arkansas to focus on action research projects. Action research projects engage fellows in an iterative, reflective process of collaborative problem-solving within their communities of practice. Specifically, fellows identify and address real-world problems within their schools (e.g., low student engagement, gaps in academic achievement) and use school-based data to design interventions aimed at improving educational outcomes. Interventions are subsequently implemented and evaluated in collaboration with IMPACT staff, cohort peers, and site-based colleagues and stakeholders. This transforms problem-solving and decision making into a community process that strengthens social bonds and promotes caring within the organization (Smylie et al., 2020). By engaging leaders in active learning that is situated within their professional contexts, fellows are provided with authentic, meaningful opportunities to practice their emerging leadership skills (Cosner et al., 2018a). Furthermore, by grounding their leadership practice in data and research, fellows learn to make informed decisions that are responsive to the needs of their schools and communities. This relational and evidence-based approach ensures that initiatives are both effective and sustainable.

The seminar series is important in shaping the relational ethos of IMPACT by providing fellows ongoing opportunities to collaborate with peers, mentors, and educational leaders across the state. Each experience is designed to engage fellows in deep reflection and collaborative learning that has practical application to leaders in high-poverty schools. Because the work is collaborative, it also allows leaders to practice intellectual humility, as they learn to hear others’ perspectives, honor their contributions, and incorporate their ideas into future decisions and actions. Seminar content is regularly adapted based on the expressed needs and interests of current fellows and alumni, and this provides a valuable opportunity to model for fellows how schools can share decision making power with stakeholders by including them in curricular and programming decisions. Furthermore, alumni often lead or participate in seminar experiences, and this is important in establishing a supportive professional network of leaders that extends across the state.

3.5. Curriculum and Pedagogy

Fellows’ relational skills are further developed through coursework. All courses in the program are taught from a stance of compassion and care for students. Faculty use a variety of instructional methods (e.g., VoiceThread, discussion boards, roleplay, case studies) to facilitate meaningful dialog among students, prompt self-reflection, and stimulate peer and faculty feedback. These methods foster the type of deep, reflective thinking that is necessary for leaders’ growth and development (Cunningham et al., 2019; Osworth et al., 2023). Moreover, faculty intentionally seek to care for fellows by inquiring about their well-being, remaining flexible and understanding of their evolving needs, and establishing class norms which welcome and value the open sharing of emotions (Lasater et al., 2021b). These practices socialize fellows to attend to and nurture their personal health and well-being, and they assist fellows in cultivating self-compassion as they navigate the complex realities of leadership.

Roleplay and reflective debriefs represent important pedagogical techniques used in fellows’ training experiences. Roleplay provides opportunities for fellows to practice their relational skills (e.g., active listening, emotional attunement), receive immediate feedback on their skills, and engage in reflective thinking and dialog around skill improvement. Roleplay is used in both coaching and class sessions. For example, fellows often roleplay intentional conversations with their coaches to prepare and receive feedback on specific questions, strategies, and conversational approaches they plan to use in their school contexts. While roleplay can be uncomfortable and intimidating at first, fellows have shared that they deeply value the opportunity roleplay provides to engage in relational skills practice in a safe, supportive environment. Roleplay is also advantageous in building fellows’ confidence and sense of efficacy in navigating tough conversations in their schools, and they offer fellows a safe space for creativity and risk-taking in their interpersonal interactions with others.

Fellows also engage in a series of reflective debriefs throughout their IMPACT experience. They are structured and sequenced so that fellows learn and practice the skills needed to coach and support teachers. The reflective debrief sessions allow fellows to practice the following: asking teachers questions which can guide their reflective practice and professional growth; giving meaningful, constructive feedback to teachers; navigating tough conversations with teachers; and supporting struggling teachers. These scenarios often involve the delivery of difficult feedback; thus, they provide a valuable opportunity for fellows to practice and receive feedback on resolving conflicts with others. They also help leaders emotionally attune to others, which is an essential first step to compassionate responding. Because reflective debriefs are roleplayed, fellows can practice their relational and conflict resolution skills without the fear of damaging real relationships. Following the reflective debriefs, fellows receive direct feedback from their coaches and peers on their communication and relational skills. Feedback often focuses on helping fellows think about and remain sensitive to the emotional experiences of teachers in the scenarios, consider compassionate actions to support teachers, and offer constructive feedback in a manner that builds teachers’ relational competencies.

While these themes run throughout the curriculum, one course in the program is specifically dedicated to relationship development, particularly between families, schools, and communities. This course is designed to (a) deepen students’ understanding of authentic family–school–community partnerships and the leader’s role in developing meaningful partnerships; (b) critically examine individual, institutional, and sociopolitical factors which influence family-school partnerships; and (c) build leaders’ capacity to personally connect with families and to cultivate partnership cultures within their schools. In-class and out-of-class activities are designed to engage students in critical self-reflection related to the following: their positionality and its impact on current relational efforts with students and families; their assumptions, biases, fears, and insecurities that inhibit authentic relationships with families; and the skills and experiences they need to improve their relational competencies. For example, students regularly engage in prompted journal reflections and discussions that require them to deeply reflect on their relationships with others. Examples of questions which guide this reflection include the following: What do you know about yourself that impacts how you work with families? What role does vulnerability and benevolence play in the development of trust? What messages do I send families about their value? How does social position influence the extent to which families are welcomed in schools? These types of questions “help us take stock of our relational commitments to economically marginalized students because they force us to reveal to ourselves the biases and presumptions we carry into interactions with them” (Gorski, 2018, p. 144).

Class readings, podcasts, and videos further challenge fellows to consider humanistic aspects of leadership, and class conversations intentionally incorporate language which is emotional and relational in nature (e.g., compassion, courage, vulnerability, shame, fear, love). Example readings from the course have included Dare to Lead by Brown (2018), Caring School Leadership by Smylie et al. (2020), and Compassion in Organizational Life by Kanov et al. (2004). Students are also encouraged to listen to compassion-centered, wellness-based podcasts, such as Hidden Brain’s Wellness 2.0: When It’s All Too Much, US 2.0: What We Have in Common, and Relationships 2.0: How to Keep Conflict from Spiraling. Discussion board prompts further encourage students to reflect on readings, podcasts, and videos to guide their compassion-based practice as emerging leaders. As an example, one discussion board prompt states the following:

Wellness is further promoted in the class through a session focused specifically on self-compassion, self-awareness, and well-being. In this session, students identify their core values and develop self-care strategies aligned with their values that can nourish their well-being. Ultimately, class experiences encourage fellows to embrace “wholeheartedness” in their future work as leaders (Brown, 2018, p. 72).Limited time and heavy workloads are often cited as obstacles to building authentic family-school partnerships. Fortunately, the literature on compassion, trust, and vulnerability offers us hope in this regard. As Brown (2018) states, “It turns out that trust is in fact earned in the smallest of moments. It is earned not through heroic deeds, or even highly visible actions, but through paying attention, listening, and gestures of genuine care and concern” (p. 32). Existing literature consistently points to the power of small acts of compassion and care—acts that may even seem invisible at times. Yet these small acts can have a profound, positive impact on the individual receiving them, and when embedded into organizational culture, they can have a profound, positive impact on the entire organization. Take a few moments to pause and think deeply about this. When I think about this, it says to me that compassion and care do not equate to grand gestures. Rather, they simply require doing our everyday work from an intentional stance of compassion and care. Imagine approaching your everyday work from an intentional stance of compassion and care. What would this look like? What small changes to your practice would you need to make? How might your interactions change with students, families, coworkers, etc.? What would it feel like to make these changes?

This course also provides students with explicit instruction and skill practice related to effective communication and relationship development. For example, one class session focuses on effective communication skills. During this class, students are taught how to engage in active listening, question appropriately, use reflection to verify the speaker’s affective message, and deescalate volatile situations. Students are then asked to roleplay having a “tough conversation” with a parent. Students are divided into groups of three. One student plays the role of school leader, one student plays the role of parent, and the third student plays the role of observer. During the roleplay, students are encouraged to refrain from problem-solving and, instead, to focus exclusively on ensuring the parent feels heard, cared for, and respected. Following the roleplay, the observer and parent provide feedback to the school leader specific to their relational skills. Group members then switch roles until each student acts as parent, leader, and observer. Following the roleplay, students are asked to journal about their relational strengths and opportunities for growth. The session concludes with a class debrief. A common sentiment expressed by students during the debrief is that the roleplay exercise helps them better recognize their natural tendency to respond defensively and/or immediately engage in problem-solving. Students have also shared that they believe a more intentional focus on attending, listening, and responding skills could help them cultivate compassionate responses to others’ experiences and more productively resolve conflicts, particularly as they develop habits around authentic listening and ensuring others’ perspectives are heard and valued.

Another important component of this course is the development of a community asset map and resource directory that can be used to support family–school partnerships. As part of this exercise, students are required to speak with diverse stakeholders (e.g., district leaders, business owners, civic leaders, school- and community-based mental health professionals, parents, community members) to identify the strengths of their communities. Identifying community assets is a powerful way to move away from deficit-based views of low-income communities and can help strengthen family–school–community partnerships (Gorski, 2018). Ultimately, this exercise requires students to engage in and with their communities, and it results in the development of a living resource which is used to support students, families, educators, and community members within fellows’ school communities.

Class readings and discussions also help students develop a deeper understanding of effective conflict resolution. Students are taught to engage in perspective-taking, appreciate difference, practice compromise and flexibility, listen with an open mind and heart, share decision making power with families, remain open to feedback, reframe conflict as an opportunity for deeper understanding, and consider how their approach to managing conflict influences the development of trusting relationships. Through these learning experiences, fellows are provided with opportunities to engage in the critical reflection necessary to improve their relational practices while also gaining authentic opportunities to communicate and connect with members of their school communities. Anonymous feedback provided via course evaluations suggests that students largely consider the course valuable in advancing their ideological understanding of partnership development and offering them practical knowledge which directly translates to their work as educators. As students have described, “I learned to analyze parent and leadership relationship more critically. I have even been able to share the knowledge I have gained from this course in a professional development in my school learning community”; “This course and the course readings allowed me to reflect and think critically about my growth as a leader in my school and the partnerships that are vital to the success of schools”; “I felt challenged and spent a lot of time reflecting on my interactions with others—personally and professionally”; and “I didn’t feel like the work was assigned for the sake of assigning it. Each assignment was meaningful, gave me a new perspective, and deepened my knowledge”.

Fellows further learn to navigate and deescalate conflicts through their school law course. One faculty member in the program is a Certified Mediator in Arkansas; he uses his expertise in mediation to help students approach conflicts from a communicative perspective (see discussions in Hendry, 2010; Msila, 2015). Specifically, fellows learn to consider how they might identify stakeholders involved in a dispute, articulate a shared goal that is in the best interests of students, bring stakeholders together to understand the root of their disagreement, and co-construct actions which move stakeholders toward their articulated end goal.

3.6. Internship

The internship serves as one of the primary mechanisms for equipping leaders with leadership skills, dispositions, and knowledge to work in high-poverty schools. This is accomplished by emphasizing support for students with different needs and backgrounds, community engagement, data-driven decision making, resilience and adaptability, and collaborative leadership in internship experiences. Aspiring leaders need opportunities to engage in a broad range of authentic internship experiences that allow them to effect change for their students, schools, and communities (Sherman & Crum, 2009). The IMPACT program addresses this need by embedding student internships within their coursework and engaging fellows in field-based practice-oriented learning experiences (Cosner et al., 2018a) which are aligned with course objectives. For example, one internship activity requires fellows to conduct a culture survey, present the survey data to the school’s leadership team, and collaborate with the team to develop a culture-based action plan. Internship activities allow students to apply course content to their professional practice, assume leadership roles within their schools, and engage in experiential learning over their entire program of study. This model requires ongoing collaboration between the university program and school site, as they partner to create meaningful learning experiences for fellows which support leaders in becoming change agents within their schools, districts, and communities (Drago-Severson, 2009; Sherman & Crum, 2009).

Internship activities also provide fellows authentic opportunities to navigate complex relational dynamics associated with leading school improvement efforts. For example, one internship activity involves the development and implementation of a family and community involvement night. This activity requires fellows to collaborate with internal and external stakeholders to create an event that is responsive to their community’s unique needs and interests. One fellow partnered with the local Boys and Girls Club to host an exhibit featuring students’ work. Initially, the fellow faced opposition from her district related to this event; however, she was able to work with community members to plan an event that complied with the district’s requirements and simultaneously met families’ needs. This event was so well received that community members lined up around the block to attend, and the superintendent vowed to continue the event in future academic years. Through this experience, the fellow learned to negotiate and respond to diverse interests, collaborate with community-based agencies to advance school functions, disrupt deficit-based perspectives of students and families, and advocate for practices which could strengthen family–school–community connections. Ultimately, internship activities, such as the family and community involvement night, provide fellows with the opportunity to engage in authentic dialog with community members, better understand their community’s interests and needs, and learn from and with students, families, and community members.

3.7. Mentoring and Coaching

Mentorship and coaching are cornerstones of the IMPACT experience. The IMPACT program utilizes a partnership-based approach to mentorship in which students have access to ongoing, collaborative support from multiple IMPACT partners. These partners include on-site mentors, IMPACT program administrators and leadership advisors, alumni ambassadors, and University of Arkansas educational leadership faculty members. This partnership-based approach to mentorship ensures students are provided with the following: (a) access to mentors with diverse personal and professional experiences (Drago-Severson et al., 2013; Mullen et al., 2020; Sherman & Crum, 2009); (b) continuous site-based coaching; (c) opportunities to collaborate in a variety of professional activities (Hayes, 2019); (d) care as people and professionals (Lasater et al., 2021b); (e) comprehensive support as they prepare to lead in diverse school contexts. These various partnerships also ensure that mentorship is maintained across fellows’ career trajectories (i.e., from preservice preparation to the principalship).

Leadership advisors play an especially important role in fellows’ development. Leadership advisors serve as full-time coaches in the program, and they are certified in the Cognitive Coaching model. Currently, there are two leadership advisors within the IMPACT program, and each fellow is assigned to one advisor. Leadership advisors provide intensive one-on-one support to fellows throughout their programs of study, which ensures that fellows receive feedback and support that spans the entirety of their preparation experience (Cosner & De Voto, 2023). Coaching support includes biweekly coaching sessions, one formal classroom observation, and one formal leader debrief observation. During coaching sessions, fellows and advisors collaboratively engage in problem-solving, decision making, and reflection related to site-specific issues. Coaching sessions also provide an opportunity for leadership advisors to support and prioritize fellows’ well-being. Whenever fellows are struggling, coaches often include action steps related to self-care on fellows’ developmental plans.

The Cognitive Coaching model is important in supporting leaders’ continuous professional growth. Cognitive Coaching facilitates deep reflection, reflective dialog, and thoughtful questioning between leadership advisors and fellows. Key components of this approach include self-directed learning, reflective practice, the contextual application of learning, and building leaders’ sense of self-efficacy. Fellows prepare for their biweekly coaching sessions by journaling about their experiences in relation to the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders (PSELs) and IMPACT’s disposition rubric. This process helps fellows develop a deeper understanding of their leadership practices and align them with national standards and program-specific expectations. Finally, Cognitive Coaching assists leaders in developing the knowledge and skills needed to facilitate adult learning in their schools. Specifically, fellows learn to plan meaningful professional development and to foster caring, compassionate school cultures.

Because fellows complete their coursework and internship simultaneously, fellows immediately receive support and feedback from their leadership advisor as they apply knowledge and skills learned in coursework. This also allows leadership advisors to tailor internship experiences and feedback to the specific needs of fellows, which can help ensure that aspiring leaders are exposed to learning experiences which are responsive to school-based needs (Cosner & De Voto, 2023). Leadership advisors also conduct two formal observations of fellows. First, advisors conduct a classroom teaching observation using Arkansas’s Teacher Excellence and Support System (TESS) formative evaluation model. This observation takes place prior to fellows’ admission to the program and offers the opportunity to observe fellows’ teaching practices, values, and skills, as well as their interactions with students. Second, advisors conduct a leader debrief observation. During this experience, fellows conduct an observation of a teacher within their building and provide post-observation feedback to the teacher. Leadership advisors observe this feedback session, and they subsequently engage in reflective dialog with fellows on their delivery of feedback and support of the teacher. These debrief sessions help fellows develop the skills, knowledge, and experiences necessary to impact adult development within their schools.

Fellows receive additional coaching and mentorship from their university instructors, university-based internship supervisor, and site-based internship supervisor. These multifarious opportunities for coaching and mentoring ensure that “practice experiences and the surrounding situational context” are “harnessed as learning resources during coaching interactions” (Cosner et al., 2018b, p. 377), particularly through the feedback, support, guidance, and resources they provide. Fellows also receive peer mentorship through the ambassador and alumni network (further described in Section 3.8).

3.8. Post-Graduation Support Through the Ambassador and Alumni Network

In June 2021, the ambassador and alumni network was established to strengthen the support fellows receive during coursework and post-graduation as they transition into leadership positions. The network consists of two alumni ambassadors (one currently serving as a teacher leader and one currently serving as a building-level leader) from the first seven IMPACT cohorts. Alumni ambassadors are chosen to represent their cohorts through a selective process involving nomination by their fellow cohort members and final selection by IMPACT staff. Selection is based on fellows’ demonstrated excellence within their coursework, coaching relationship, and professional setting.

The alumni and ambassador network plays an important role in fostering a community of care and establishing structural support to nourish this community (Smylie et al., 2020). Alumni ambassadors assume ownership of the network and are tasked with enacting the network in ways which meet fellows’ developmental needs. The ambassador and alumni network creates opportunities for fellows to plan, manage, and direct their learning across their career trajectories with a network of supportive peers (Cunningham et al., 2019). Currently, ambassadors provide professional development to fellows, they develop IMPACT promotional materials, and they assist with recruitment by nominating new fellows. Most importantly, ambassadors facilitate networks of support for leaders across the state, and these social networks decrease leaders’ feelings of isolation and enhance their sense of community—both of which are important to nurturing leaders’ professional growth, well-being, and sustainability in the field (Anderson et al., 2020; Kutsyuruba et al., 2024; Shirley et al., 2020; Theoharis, 2009).

3.9. IMPACT Achievements

Thus far, the IMPACT program has collected broad outcome data, such as graduation rates and pass rates on the state licensure exam. However, empirical data specific to fellows’ relational understandings and practices have not yet been collected. Moving forward, it would be advantageous to collect data related to fellows’ relational skills before and after program completion. Data could be collected by observing fellows’ relational practices via roleplay upon entry to and exit from the program. Qualitative data on fellows’ experiences in the program, sense of self-efficacy with navigating relational dynamics, and overall well-being would also provide valuable program insights.

Anecdotal evidence currently suggests that alumni value the relational nature of IMPACT and believe that it is salient in their leadership development. According to Jenni Phomsithi, a Cohort 5 alumna and current principal at SC Tucker Elementary in the Danville School District, relationships are the cornerstone of the IMPACT experience:

Everything that is poured into the IMPACT Fellow experience is amazing—classes, coaches, virtual meetings—but the binding piece is the collaboration and relationships that develop. A lot of the magic of the IMPACT program is in the relationships...There were always tough, honest conversations with coaches and a lot of feedback. I loved how they changed the learning experience to adapt to my needs. I carry much of what I learned with me every day, including how I problem-solve with groups and have difficult conversations.(Magsam, 2023)

4. Implications for Leadership Preparation Programs

There are currently limited reports detailing leadership preparation program design, development, and subsequent pedagogical features (Cosner, 2020), especially with respect to how relationships are taught, nurtured, and prioritized in leadership development. Nevertheless, we believe that leadership preparation represents a critical time to develop leaders’ relational competencies, and we further believe that centering relationships in leader preparation has the potential to shift “conceptualizations of leadership” (Osworth et al., 2023, p. 692) in ways which signal the value of care, compassion, and connection in school improvement processes. The IMPACT program is designed with these beliefs in mind. While many of the program features described in this paper (e.g., authentic learning experiences, mentoring and coaching, peer networking) are routinely recognized as important aspects of effective leadership preparation (Cosner, 2020; Cunningham et al., 2019), it is our intentional centering of relationships within the features that contributes to existing scholarship and practice. For leadership preparation programs that wish to similarly capitalize on the power of relationships in leaders’ development and, more broadly, school improvement processes, we recommend careful attention to (a) program design and structure, (b) program faculty’s modeling of relational values, and (c) student learning experiences which promote relational skill development.

4.1. Program Design and Structure

As a starting point, preparation programs should articulate relational care, compassion, and intellectual humility as core program values (Smylie et al., 2020) and subsequently create norms, routines, practices, structures, and policies which reinforce these values (Deal & Peterson, 2009). This can be carried out by incorporating caring language in all program materials (e.g., website, handbook) and ensuring that program policies reflect a commitment to students’ well-being. Additionally, programs can incorporate relational objectives into coursework and create learning experiences (e.g., readings, assignments) which challenge students to consider the relational implications of course content. An example assignment might require aspiring leaders to collaborate with members of their communities to align school mission and vision statements to the principles of caring, compassionate relationships (Smylie et al., 2020).

Preparation programs could also create structures which prompt collective responding to students’ distress (Frost et al., 2006; Worline & Dutton, 2021). In the IMPACT program, this is carried out through the development of student support plans, which ensure that students receive additional support and resources during times of personal or professional struggle. This type of structure alerts organizational members to students’ hardships and facilitates an individualized, compassionate response designed to meet students’ needs (Kanov et al., 2004).

Finally, programs should be designed and structured in ways which maximize opportunities for collaboration and mentorship. For example, preparation programs can create social networks of current and aspiring leaders which nurture students’ development and well-being across career experiences (Briscoe, 2019; Theoharis, 2009). They can also create structures which expose aspiring leaders to diverse mentors with a wide range of personal and professional experiences (Drago-Severson et al., 2013; Mullen et al., 2020; Sherman & Crum, 2009). Opportunities for collaboration and mentorship not only nurture leaders’ development and well-being (Lasater et al., 2021b; Varney, 2009), but they also equip leaders with the knowledge and skills needed to facilitate adult development within their own school communities (Hayes, 2019).

4.2. Modeling Relational Values

Faculty in leadership preparation programs can further promote leaders’ relational development by modeling care, compassion, and intellectual humility in their interactions with students. Specifically, faculty can create intentional opportunities for interaction with students (Cosner, 2009; Worline & Dutton, 2021) and use these opportunities to emotionally attune to each other’s experiences, explicitly communicate relational values, and reciprocally support each other’s well-being (Lasater et al., 2021b). For example, faculty members could model interpersonal knowing and connection by greeting students by name, providing student feedback which acknowledges joy and suffering, sharing personal stories of success and hardship, and co-constructing class norms of respect, trust, compassion, and care for others (Worline & Dutton, 2021).

Faculty members can further model relational values by practicing healthy self-care practices and openly exhibiting compassion for the self. This involves openly pursuing wellness and engaging in self-care practices which are personally meaningful and restorative (Lasater, 2024). For example, John signals his prioritization of health and well-being by calendaring exercise into his daily routine and communicating this calendaring approach to students. Kara listens to wellness-related podcasts and intentionally shares what she learns with students.

Modeling relational values also necessitates that faculty openly express emotions, including setbacks and struggles, in ways which push conversations toward growth, hope, and future well-being (Lawrence & Maitlis, 2012). This open sharing not only humanizes faculty, but it also frees students to share the totality of their experiences too (Lasater et al., 2021b; Lawrence & Maitlis, 2012). By orienting conversations toward hope, growth, and well-being, even in the face of setbacks or personal failures, faculty model for students how to shift self-talk toward kinder, more compassionate ways of treating oneself (Neff, 2011).

4.3. Explicit Instruction on Relational Skill Development

Finally, leadership preparation programs can create learning experiences which explicitly cultivate students’ relational skills and competencies. Specifically, students need opportunities to practice active listening, effective communication, trust-building, emotional attunement, perspective-taking, and conflict resolution (Lasater, 2016; LaVenia et al., 2024; Smylie et al., 2020; Tschannen-Moran, 2014). Preparation programs can support students in developing these skills by embedding explicit instruction and skill development into coursework and internship experiences (Smylie et al., 2020). Effective pedagogical techniques for teaching these skills include journaling, reflective dialog, observing models, listening to model narratives, and roleplay (Cunningham et al., 2019; Smylie et al., 2020). Critical to any of these techniques are opportunities for faculty to provide direct feedback to students specific to their relational skills (Lasater, 2016). It is through clear, direct feedback that students can reflect on their relational skills, cultivate increased self-awareness around their verbal and nonverbal communication patterns, and continually refine their relational practices.

4.4. Concluding Thoughts

We are optimistic about the potential of leadership preparation programs to reorient the field toward more caring, compassionate, and nourishing educational experiences for all members of the school community, but we also recognize that the ability of leadership preparation to guide the field in this direction necessitates that programs, departments, colleges, and universities attend to their own academic cultures first. Future educators are likely to reproduce the educational environments provided for them (Bosetti et al., in press). If we desire educators to create school spaces that prioritize the holistic development and well-being of students, families, and community members, then we must create spaces where they see and benefit from that environment too. This can be difficult in high-pressure academic environments that incite performativity, individualism, and competition for resources and opportunities, rather than care and connection with others (Bosetti et al., in press). As such, we encourage faculty in educational programs, departments, and colleges to take seriously their role in establishing practices, policies, routines, and systems which legitimize, propagate, and coordinate compassion across their units (Kanov et al., 2004). They should further take seriously their role in socializing future leaders to cultivate “educational workplace cultures that promote and encourage human flourishing” (Bosetti et al., in press). Educational leadership faculty can engage in this work by actively sharing stories of relational care and compassion on their campuses and within their scholarship communities. They can also guide the development of a relational, compassionate ethos within the systems that support their work by engaging in shared governance and faculty campus leadership. When leadership preparation programs center relationships within their work, they unleash the generative power of compassion (Dutton & Workman, 2011) and set in motion the creation of educational spaces which are engaging, uplifting, and deeply connective. This type of environment not only sustains leaders in their work, but it allows them to flourish (Kutsyuruba et al., 2024).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L. and J.C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, K.L. and J.C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was not supported by external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This paper does not meet the definition of research involving human subjects in the federal regulations and, thus, does not require IRB approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

As described in the manuscript, Pijanowski created IMPACT and is the original and current PI of the program. Pijanowski and Lasater both teach in the IMPACT program.

References

- Allen, J. (2007). Creating welcoming schools: A practical guide to home-school partnerships with diverse families. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anast-May, L., Buckner, B., & Geer, G. (2011). Redesigning principal internships: Practicing principals’ perspectives. The International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E., Cunningham, K. M. W., & Eddy-Spicer, D. H. (2024). Leading continuous improvement in schools. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E., Hayes, S., & Carpenter, B. (2020). Principal as caregiver of all: Responding to needs of others and self. CPRE Policy Briefs, Consortium for Policy Research in Education. Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/8343 (accessed on 4 January 2025).