Immigrant Children and Youth in the USA: Facilitating Equity of Opportunity at School

Abstract

:1. Immigrant Children and Youth in the USA: Facilitating Equity of Opportunity at School

In just under three decades, the immigrant population has tripled in the United States. In 2007 the foreign born population of the US was 13%. (66% of all immigrants lived in six states: CA, NY, TX, FL, IL, and NJ). However, immigrant populations have grown rapidly in NC, GA, AR, SC and TN.[1]

The United States is being transformed by high, continuing levels of immigration. No American institution has felt the effect of these flows more forcefully than the nation’s public schools. And no set of American institutions is arguably more crucial to the future success of immigrant integration.[2]

2. Immigrants and Schools

- A large part of our dropout problem is that so many immigrant students leave early to go to work;

- Immigrant girls are leaving school because their families have arranged marriages for them as early as 14 years of age;

- The refugee organization in our community is bringing in many families whose children have never been in school;

- Our schools have families who speak many different languages, and we don’t have enough translators to facilitate communication;

- On campus, student groups establish their territory and newcomers not only aren’t invited in, they are stigmatized (e.g., labeled FOB—Fresh Off the Boat);

- Our ELL students aren’t doing well learning English and aren’t showing progress on the state achievement tests; this is having a serious negative impact on our average yearly progress;

- Many parent are unhappy because we are not helping their children maintain their home language;

- Unannounced immigration raids at the packing plants during the school day led to countless numbers of children coming home to find no adult there.

2.1. A Quick Look at the Numbers

2.2. What Does this Mean for Schooling?

Legally: “All children in the USA, are entitled to equal access to a public elementary and secondary education without regard to their or their parents’ actual or perceived national origin, citizenship, or immigration status. This includes recently arrived unaccompanied children, who are in immigration proceedings while residing in local communities with a parent, family member, or other appropriate adult sponsor. Under the law, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is required to care for unaccompanied children apprehended while crossing the border. While in care at a HHS shelter, such children are not enrolled in local schools but do receive educational services and other care from providers who run HHS shelters. Recently arrived unaccompanied children are later released from federal custody to an appropriate sponsor—usually a parent, relative, or family friend—who can safely and appropriately care for them while their immigration cases proceed. While residing with a sponsor, these children have a right under federal law to enroll in public elementary and secondary schools in their local communities and to benefit from educational services, as do all children in the U.S.”.[7]

3. Appreciating Differences in Why Families Migrate

3.1. Seeking Economic Opportunity

3.2. Seeking Family Reunification

3.3. Seeking Refuge

There are differences between first-generation immigrants who come as refugees and those coming through family reunion, as well as differences between those coming from war areas and those who do not have such experiences. This is partly a matter of having had any access to schooling before arriving in the host country, partly a matter of the extent to which one has experienced traumas or having or not having someone to relate to when arriving.[24]

4. Concerns about Immigrant Students

While the emphasis in this paper is on addressing concerns, we again want to stress that some immigrant youth display remarkable resilience and rise above their negative experiences. Schools need to understand and promote resilience [41]. For example, from a motivational perspective, research suggests that resilience is associated with experiences that enhance feelings of competence, relatedness, and connectedness with others.[18]

Successful adaptations among immigrant students appear to be linked to the quality of relationships that they forge in their school settings. ...Social relations provide a variety of protective functions—a sense of belonging, emotional support, tangible assistance and information, cognitive guidance, and positive feedback. ...Relationships with peers, for example, provide emotional sustenance that supports the development of significant psychosocial competencies in youth. ...In addition, connections with teachers, counselors, coaches, and other supportive adults in school are important in the academic and social adaptation of adolescents and appear to be particularly important to immigrant adolescents.[34]

5. Prevailing School Practices for Addressing Immigrant Concerns

6. A Sample of Current School and Neighborhood Programs in the USA

6.1. Examples of School-Based Supports in the USA that Have Relevance for Schools Elsewhere

6.1.1. Welcome Centers and Newcomer Programs

6.1.2. Family Involvement

When looking at the growing immigrant population, two-generation strategies often focus on parental involvement in education...engaging them more fully in the educational process in the home, school and community could bring academic returns for their children. For the most part, these efforts have targeted parental involvement through, for example, programs to help immigrant parents construct home literacy environments or to help teachers better communicate with immigrant parents. Yet, attempts to alter the barriers to involvement behavior through, for example, programs to help parents increase their education or their own English proficiency, have also gained traction.[50]

6.1.3. Language Acquisition and Quality Instruction

English as a Second Language

In spite of their striking diversity, English learners in secondary schools have typically been lumped into the same English as a Second Language (ESL) classroom, with one teacher addressing the needs of students with dramatically varied English proficiency, reading, and writing skills. In elementary schools, a common practice is to pull out English learners across grades K-5 for thirty minutes of ESL instruction. For the remainder of the day these English learners attend regular classes in a sink‑or‑swim instructional situation, usually with teachers who are unprepared to teach them.[53]

Instruction in General

General Principles for Developing Effective Teaching and Learning Contexts for Immigrants Adolescents

6.1.4. Professional/Staff Development

6.2. Examples of Related Community Supports

6.2.1. Family Services and Resources

6.2.2. Mental Health Supports

6.2.3. Refugee Orientation

6.2.4. Immigration Raids Aftermath Support

7. Broadening What Schools and Communities Do

7.1. Needed: Language and Much More

7.2. Toward a Comprehensive System of Student and Learning Supports

7.2.1. Prototype Intervention Framework

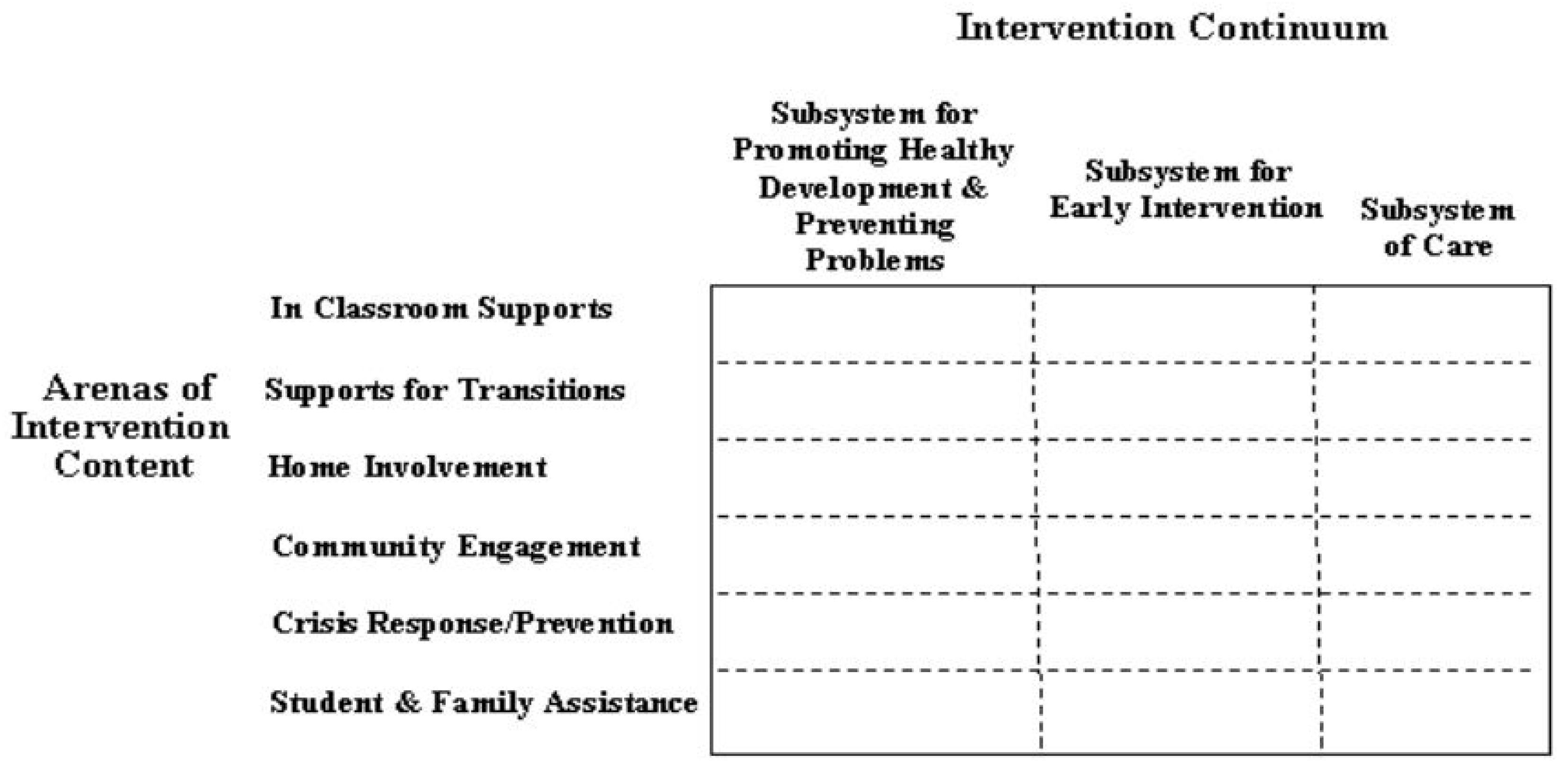

7.2.2. A Continuum of Unified and Interconnected Subsystems

- promoting healthy development and preventing problems;

- intervening early to address problems as soon after onset as is feasible; and

- assisting with chronic and severe problems.

7.2.3. Content Arenas of Activity

- Enhancing strategies in regular classrooms to enable learning. This arena emphasizes in classroom collaboration with other teachers and student support staff to (a) enable personalized instruction; (b) enhance intrinsic motivation for all students and especially those manifesting mild-moderate learning and behavior problems; (c) provide learning accommodations and supports as necessary; (d) address external barriers with a focus on prevention and early intervening; (e) use response to intervention in applying special assistance; and (f) re-engage those who have become disengaged from learning at school.

- Supporting transitions. This arena emphasizes assisting students and families as they negotiate the many hurdles related to school and grade changes, daily transitions, program transitions, accessing supports, and so forth. For example, it stresses welcoming and providing ongoing social support for students, families, and staff new to the school to provide both a motivational and a capacity building foundation for developing positive working relationships and a positive school climate. It focuses on facilitating school adjustment and early identification of adjustment problems. It provides a focus on transitions to and from special programs.

- Increasing home and school connections and engagement. This arena is concerned with (a) addressing barriers to home involvement; (b) helping those in the home enhance supports for their children; (c) strengthening home and school communication; and (d) increasing home support of the school. It emphasizes expanding the nature and scope of interventions and enhancing communication mechanisms for outreaching in ways that connect with the motivational differences manifested by parents and other student caretakers and developing intrinsically motivated school-home working relationships.

- Increasing community involvement and collaborative engagement. This arena is concerned with outreach to develop greater community connection and support from a wide range of entities to better address barriers to learning, promote child and youth development, and establish a sense of community that supports learning and focuses on hope for the future. It includes (a) enhanced use of volunteers and other community resources; (b) weaving together school and community efforts to enhance the range of options and choices for students, both at school and in the community; and (c) establishing a school‑community collaborative.

- Responding to, and where feasible, preventing school and personal crises. This arena includes preparing for emergencies, implementing plans when an event occurs, countering the impact of traumatic events, developing and implementing prevention strategies, and creating a caring and safe learning environment. Widely used school crisis teams can go beyond crisis response and provide proactive leadership in developing prevention programs to avoid or mitigate crises. Such programs can enhance protective buffers and student intrinsic motivation for preventing interpersonal and human relationship problems.

- Facilitating student and family access to special assistance (including specialized services on- and off-campus) as needed. This arena encompasses providing personalized support as soon as a need is recognized. The emphasis in doing so is on assisting in the least disruptive way using a shared and mutually respectful problem-solving approach. Special attention is given to minimizing threats to and enhancing intrinsic motivation for solving problems by strengthening feelings of competence, self-determination, and positive relationships.

8. Policy Implications

8.1. A Policy Paradigm Shift

- unifying the many separate organizational and operational infrastructure entities that have been built up around the piecemeal and ad hoc establishment of initiatives, programs, and practices;

- identifying dedicated leadership positions for the component;

- redefining job descriptions of student and learning support personnel;

- connecting relevant resources across families of schools;

- enhancing collaboration with community resources to weave together overlapping functions and related resources into a comprehensive system; and

- pursuing relevant professional and other stakeholder development and facilitating essential systemic changes.

8.2. A Caution about Limiting Policy to Integrating Services

8.3. Recommendations

- adopting a comprehensive intervention blueprint for student and learning supports and identifying which current strategies are worth keeping and what major gaps need to be filled;

- redeploying available resources in keeping with priorities for system development;

- revamping school‑community infrastructures to weave resources together to enhance and evolve the system and align interventions horizontally and vertically; and

- supporting the necessary systemic changes in ways called for by comprehensive transformation, scale‑up, and sustainability.

- (1)

- Move beyond the current marginalized and fragmented approaches to initiate development of a comprehensive pre‑K-16 system of student and learning supports. Specifically, we propose:

- Moving the current pre‑K-16 school policy framework to a three‑component blueprint so that the many fragmented efforts to address barriers to success at school and re-engage disconnecting/non‑persevering students are unified under one umbrella concept and developed into a comprehensive system of student and learning supports;

- Ensuring that this third component is treated as equal to the others in policy priority to end the marginalization of student and learning supports and to minimize piecemeal and ad hoc intervention planning and implementation;

- Expanding the school accountability framework to encompass the third component and drive development of a comprehensive system.

- (2)

- Revamp and interconnect operational infrastructures. Developing and institutionalizing a comprehensive system of student and learning supports requires a well‑designed and effective set of operational mechanisms. The existing ones must be modified in ways that guarantee new policy directions are implemented effectively and efficiently. How well these mechanisms are connected horizontally and vertically determines cohesiveness, cost efficiency, and equity.

- (3)

- Support transformative and sustainable systemic change. Systemic transformation to enhance equity of opportunity across pre-K-16 requires new collaborative arrangements and redistributing authority (power). Policymakers must provide support and guidance not only for implementing intervention prototypes, but also for adequately getting from here to there. This calls for well‑designed, compatible, and interconnected operational mechanisms at many levels and across agencies.

9. Concluding Comments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fortuny, K.; Chaudry, A.; Jargowsky, P. Immigration Trends in Metropolitan America, 1980–2007; The Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-De-Velasco, J.; Fix, M.; Clewell, B. Overlooked and Underserved: Immigrant Students in U.S. Secondary Schools; The Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Hispanic Center. A Nation of Immigrants; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Hispanic Center. Second‑Generation Americans: A Portrait of the Adult Children of Immigrants; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fortuny, K.; Hernandez, D.J.; Chaudry, A. Young Children of Immigrants: The Leading Edge of America’s Future. Brief 3; The Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nwosu, C.; Batalova, J.; Auclair, G. Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States; Migration Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Educational Services for Immigrant Children and Those Recently Arrived to the United States. 2015. Available online: http://www2.ed.gov/policy/rights/guid/unaccompanied‑children.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Bal, A.; Perzigian, A.B.T. Evidence‑based interventions for immigrant students experiencing behavioral and academic problems: A systematic review of the literature. Educ. Treat. Child. 2013, 36, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, M.; Doll, H.; Stein, A. A school-based mental health intervention for refugee children: An exploratory study. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2009, 14, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagelbaum, A.; Carlson, J. Working with Immigrant Families: A Practical Guide for Counselors. Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A.; Rumbaut, R.G. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A.; Zhou, M. The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1993, 530, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudry, A.; Fortuny, K. Children of Immigrants: Economic Well-Being; The Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Perreira, K.M.; Crosnoe, R.; Fortuny, K.; Pedroza, J.; Ulvestad, K.; Weiland, C.; Yoshikawa, H.; Chaudry, A. Barriers to Immigrants’ Access to Health and Human Services Programs; ASPE Issue Brief; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- American Community Survey. The Foreign‑Born Population in the United States: 2010; U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Capps, R.; Passel, J. Describing Immigrant Communities; Foundation for Child Development and the Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozoco, C.; Bang, H.J.; Kim, H.Y. I felt like my heart was staying behind: Psychological implications of family separations & reunifications for immigrant youth. J. Adolesc. Res. 2010, 26, 222–257. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Moller, A.C. The concept of competence: A starting place for understanding intrinsic motivation and self-determined extrinsic motivation. In Handbook of Competence and Motivation; Elliot, A.J., Dweck, C.J., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 579–597. [Google Scholar]

- Hagger, M.S.; Sultan, S.; Hardcastle, S.J.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D. Perceived autonomy support and autonomous motivation toward mathematics activities in educational and out-of-school contexts is related to mathematics homework behavior and attainment. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, P.M. Applying developmental psychology to bridge cultures in the classroom. In Applied Psychology: New Frontiers and Rewarding Careers; Donaldson, S.I., Berger, D.E., Pezdek, K., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Annual Flow Report: Refugees and Asylees: 2013. 2014. Available online: http://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ois_rfa_fr_2013.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2015). [Google Scholar]

- American Immigration Council. Refugees: A Fact Sheet; American Immigration Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McBrien, J. Educational needs and barriers for refugee students in the United States: A review of the literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 2005, 75, 329–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fangen, K. Social exclusion and inclusion of young immigrants: Presentation of an analytical framework. Nord. J. Youth Res. 2010, 18, 33–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, K.E.; Davidson, G.R.; Schweitzer, R.D. Review of refugee mental health interventions following resettlement: Best practices and recommendations. Am. J. Orthopsychiatr. 2010, 80, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Feliciano, C. Beyond the family: The influence of premigration group status on the educational expectations of immigrants’ children. Soc. Educ. 2006, 79, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosnoe, R.; Turley, R.N.L. Educational outcomes of immigrant youth. Future Child. 2011, 21, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, L.; Perreira, K. It turned my world upside down: Latino youth’s perspectives on immigration. J. Adolesc. Res. 2010, 25, 465–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sluzki, C. Migration and family conflict. Fam. Process 1979, 18, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perreira, K.M.; Ornelas, I.J. The physical and psychological well‑being of immigrant children. Future Child. 2011, 21, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelman, H.S.; Taylor, L. The Implementation Guide to Student Learning Supports in the Classroom and Schoolwide: New Directions for Addressing Barriers to Learning; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, D. Being ‘good’ or being ‘popular’: Gender and ethnic identity negotiations of Chinese immigrant adolescents. J. Adolesc. Res. 2009, 24, 37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez‑Orozco, M.M.; Darbes, T.; Dias, S.I.; Sutin, M. Migrations and schooling. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 2011, 40, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Orozco, C.; Rhodes, J.; Milburn, M. Unraveling the immigrant paradox: Academic engagement and disengagement among recently arrived immigrant youth. Youth Soc. 2009, 41, 151–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peguero, A.; Bondy, J. Immigration and students’ relationship with teachers. Educ. Urban Soc. 2011, 43, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, A. “The ESL kids are over there”: Opportunities for social interactions between immigrant Latino and White high school students. J. Hisp. Higher Educ. 2003, 2, 292–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peguero, A. Victimizing the children of immigrants: Latino and Asian American student victimization. Youth Soc. 2009, 41, 186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreon, G.P.; Drake, C.; Barton, A.C. The importance of presence: Immigrant parents’ school engagement experiences. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2005, 42, 465–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capps, R.; Castaneda, R.M.; Chaudry, A.; Santos, R. Paying the Price: The Impact of Immigration Raids on America’s Children; The Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- American Immigration Council. Unauthorized Immigrants Today: A Demographic Profile; American Immigration Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hooberman, J.; Rosenfeld, B.; Rasmussen, A.; Keller, A. Resilience in trauma-exposed refugees: The moderating effect of coping style on resilience variables. Am. J. Orthopsychiatr. 2010, 80, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leos, K.; Saavedra, L. A New Vision to Increase the Academic Achievement for English Language Learners and Immigrant Students; The Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tienda, M.; Haskins, R. Immigrant children: Introducing the issue. Future Child. 2011, 21, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, A. A Look at Immigrant Youth: Prospects and Promising Practices; National Conference of State Legislatures: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Short, D. Newcomer programs: An educational alternative for secondary immigrant students. Educ. Urban Soc. 2002, 34, 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, R. Newcomer schools: Salvation or segregated oblivion for immigrant students? Theory Pract. 2000, 39, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, D.J.; Rivera, M.; Lesaux, N.; Kieffer, M.; Rivera, H. Research‑Based Recommendations for Serving Adolescent Newcomers; Center on Instruction: Houston, TX, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Student Intake Center. Available online: http://www.dallasisd.org/Page/1078 (accessed on 9 August 2015).

- The ESL Newcomer Academy. Available online: http://jcps.jefferson.k12.ky.us/eslnewcomeracademy/ (accessed on 9 August 2015).

- Crosnoe, R. Two-Generation Strategies and Involving Immigrant Parents in Children’s Education; The Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Golan, S.; Petersen, D. Promoting Involvement of Recent Immigrant Families in Their Children’s Education; Harvard Family Research Project: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Education Sciences. What works clearinghouse. Available online: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Topics.aspx (accessed on 9 August 2015).

- Calderon, M.; Slavin, R.; Sanchez, M. Effective instruction for English learners. Future Child. 2011, 21, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walqui, A. Strategies for Success: Engaging Immigrant Student in Secondary Schools; WestEd: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding, S.; Carolino, B.; Amen, K. Immigrant Student and Secondary Reform: Compendium of Best Practices; Council of Chief State School Officers: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- WestEd. Bridging Cultures Project. Available online: http://www.wested.org/project/bridging‑cultures‑project/ (accessed on 9 August 2015).

- NYC Department of Youth and Community Development. Immigrant Family Services. Available online: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dycd/html/immigration/family.shtml (accessed on 9 August 2015).

- Caring Across Communities. Available online: http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/articles‑and‑news/2010/05/caring‑across‑communities.html (accessed on 9 August 2015).

- Birman, D.; Beehler, S.; Harris, E.; Everson, M.; Batia, K.; Liautaud, J.; Frazier, S.; Atkins, M.; Blanton, S.; Buwalda, J.; Fogg, L.; Cappella, E. International Family, Adult, and Child Enhancement Services (FACES): A Community-Based Comprehensive Services Model for Refugee Children in Resettlement. Am. J. Orthopsychiatr 2008, 78, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Applied Linguistics. Available online: http://www.cal.org (accessed on 9 August 2015).

- American Immigration Council. Protecting Children in the Aftermath of Immigration Raids; American Immigration Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Batalova, J.; McHugh, M. Number and Growth of Students in U.S. Schools in Need of English Instruction; Migration Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Results in Brief: National Evaluation of Title III Implementation: Report on State and Local Implementation. 2012. Available online: http://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/title-iii/state-local-implementation-report.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Hall, H. NCLB’s High-Stakes Testing Worries Districts as ELL Numbers Rise; The Tennessean: Nashville, TN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Karoly, L.A.; Gonzales, G.C. Early care and education for children in immigrant families. Future Child. 2011, 21, 71–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelman, H.S.; Taylor, L. Turning around, transforming, and continuously improving schools: Policy proposals are still based on a two rather than a three component blueprint. Int. J. Sch. Disaffection 2011, 8, 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Adelman, H.S.; Taylor, L. Embedding school health into school improvement policy. Int. J. Sch. Health 2014, 1, e24546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, H.S.; Taylor, L. Not another special initiative! Every Child J. 2014, 4, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Adelman, H.S.; Taylor, L. Integrated Student Supports and Equity: What’s Not Being Discussed? Center for Mental Health in Schools: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Mental Health in School. Transforming Student and Learning Supports: Trailblazing Initiatives! UCLA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Adelman, H.S.; Taylor, L. Transforming Student and Learning Supports: Developing a Unified, Comprehensive, and Equitable System; Center for Mental Health in Schools: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Mental Health in School. Moving Beyond the Three Tier Intervention Pyramid toward a Comprehensive Framework for Student and Learning Supports; UCLA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Mental Health in School. About Short‑Term Outcome Indicators for School Use and the Need for an Expanded Policy Framework; UCLA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Mental Health in School. For Consideration in Reauthorizing the No Child Left Behind Act. Promoting a Systematic Focus on Learning Supports to Address Barriers to Learning and Teaching; UCLA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Mental Health in School. System Change Toolkit; UCLA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adelman, H.S.; Taylor, L. Immigrant Children and Youth in the USA: Facilitating Equity of Opportunity at School. Educ. Sci. 2015, 5, 323-344. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci5040323

Adelman HS, Taylor L. Immigrant Children and Youth in the USA: Facilitating Equity of Opportunity at School. Education Sciences. 2015; 5(4):323-344. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci5040323

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdelman, Howard S., and Linda Taylor. 2015. "Immigrant Children and Youth in the USA: Facilitating Equity of Opportunity at School" Education Sciences 5, no. 4: 323-344. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci5040323

APA StyleAdelman, H. S., & Taylor, L. (2015). Immigrant Children and Youth in the USA: Facilitating Equity of Opportunity at School. Education Sciences, 5(4), 323-344. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci5040323