Biochar: A Sustainable Alternative in the Development of Electrochemical Printed Platforms

Abstract

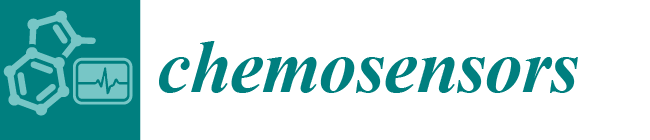

:1. Introduction

2. Chemical and Physical Characteristics of Biochar

2.1. Correlation between Biochar Characteristics and Its Production Processes

| Process | Treatment | Main Product | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermochemical | Slow pyrolysis | Biochar | [43] |

| Fast pyrolysis | Bio-oil | [44] | |

| Flash pyrolysis | Bio-oil | [45] | |

| Liquefaction | Bio-oil | [46] | |

| Gasification | Syngas | [47] | |

| Biochemical | Transesterification | Biodiesel | [48] |

| Photobiological H2 production | Hydrogen | [49] | |

| Alcoholic fermentation | Ethanol | [50] | |

| Anaerobic digestion | Methane | [51] |

2.2. Chemical Properties of Biochar

2.3. Activation Processes

2.4. Morphological and Physicochemical Properties of Biochar

2.5. Application of Biochar in Sensing

2.5.1. Carbon-Paste and Glassy-Carbon Electrodes

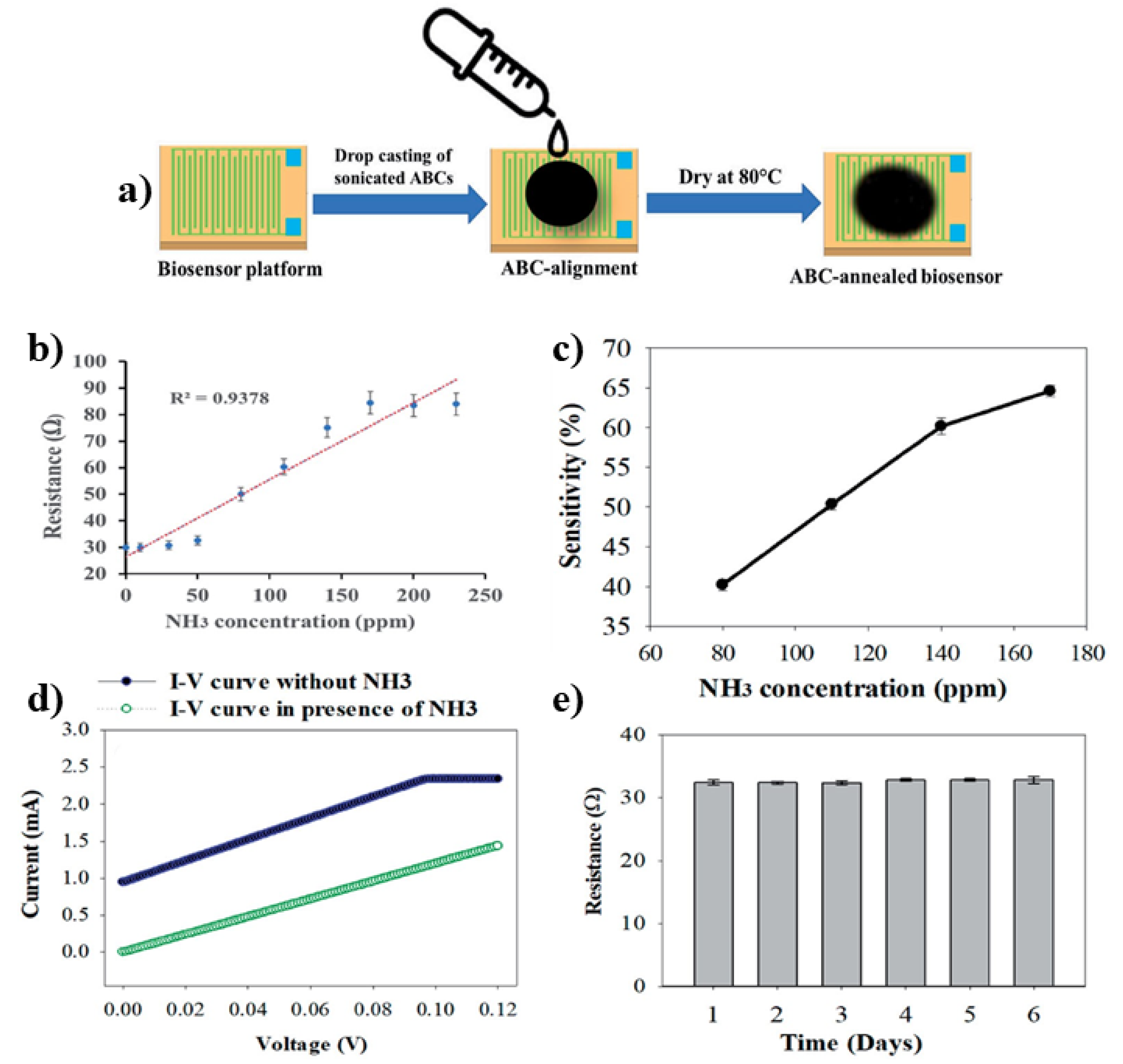

2.5.2. Biochar Application in Screen-Printed-Based Platforms

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baig, N.; Kammakakam, I.; Falath, W. Nanomaterials: A review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 1821–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahalam, L.A.; Kasi Viswanath, I.V.; Diwakar, B.S.; Govindh, B.; Reddy, V.; Murthy, Y.L.N. Review on nanomaterials: Synthesis and applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 18, 2182–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lee, H.; Ghaffari, R.; Hyeon, T.; Kim, D.-H. Recent Advances in Flexible and Stretchable Bio-Electronic Devices Integrated with Nanomaterials. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 4203–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay, J.; Srivastava, N. Application of Nanomaterials in Chemical Sensors and Biosensors, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-0-367-44073-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ur Rahim, H.; Qaswar, M.; Uddin, M.; Giannini, C.; Herrera, M.L.; Rea, G. Nano-Enable Materials Promoting Sustainability and Resilience in Modern Agriculture. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, L.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. Cellular Toxicity and Immunological Effects of Carbon-based Nanomaterials. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2019, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaytseva, O.; Neumann, G. Carbon nanomaterials: Production, impact on plant development, agricultural and environmental applications. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2016, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nsamba, H.K.; Hale, S.E.; Cornelissen, G.; Bachmann, R.T. Sustainable Technologies for Small-Scale Biochar Production—A Review. J. Sustain. Bioenergy Syst. 2015, 5, 10–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeyasubramanian, K.; Thangagiri, B.; Sakthivel, A.; Dhaveethu Raja, J.; Seenivasan, S.; Vallinayagam, P.; Madhavan, D.; Malathi Devi, S.; Rathika, B. A complete review on biochar: Production, property, multifaceted applications, interaction mechanism and computational approach. Fuel 2021, 292, 120243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.S.; Park, S.H.; Jung, S.-C.; Ryu, C.; Jeon, J.-K.; Shin, M.-C.; Park, Y.-K. Production and utilization of biochar: A review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2016, 40, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, N.L.; Pawar, A.; Salvi, B.L. Comprehensive review on production and utilization of biochar. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sohi, S.P.; Krull, E.; Lopez-Capel, E.; Bol, R. A Review of Biochar and Its Use and Function in Soil. In Advances in Agronomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 105, pp. 47–82. ISBN 978-0-12-381023-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S. Preparation, modification and environmental application of biochar: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 227, 1002–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.; Quicker, P. Properties of biochar. Fuel 2018, 217, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J. A handful of carbon. Nature 2007, 447, 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyà, J.J. Pyrolysis for Biochar Purposes: A Review to Establish Current Knowledge Gaps and Research Needs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 7939–7954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.Z.; Edvinsson, T.; Kwong, P. Biochar for electrochemical applications. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2020, 23, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfattani, R.; Shah, M.A.; Siddiqui, M.I.H.; Ali, M.A.; Alnaser, I.A. Bio-Char Characterization Produced from Walnut Shell Biomass through Slow Pyrolysis: Sustainable for Soil Amendment and an Alternate Bio-Fuel. Energies 2021, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, K.-H.; Kwon, E.E. Biochar as a Catalyst. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 77, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Hale, L.; Kar, G.; Soolanayakanahally, R.; Adl, S. Phosphorus recovery and reuse by pyrolysis: Applications for agriculture and environment. Chemosphere 2018, 194, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, M.I.; Gao, B.; Yao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Zimmerman, A.; Mosa, A.; Pullammanappallil, P.; Ok, Y.S.; Cao, X. A review of biochar as a low-cost adsorbent for aqueous heavy metal removal. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 46, 406–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, M.; Giorcelli, M.; Jagdale, P.; Rovere, M.; Tagliaferro, A. A Review of Non-Soil Biochar Applications. Materials 2020, 13, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spanu, D.; Binda, G.; Dossi, C.; Monticelli, D. Biochar as an alternative sustainable platform for sensing applications: A review. Microchem. J. 2020, 159, 105506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, T.; Wang, H.; Kearns, J.; Jenkins, P.; Ren, Z.J. Biochar as a sustainable electrode material for electricity production in microbial fuel cells. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 157, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, S.; Ulrich, R.; Harrington, A.; Stadie, N.P.; Ryan, C. Physical and chemical mechanisms that influence the electrical conductivity of lignin-derived biochar. Carbon Trends 2021, 5, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-J.; Jiang, H.; Yu, H.-Q. Development of Biochar-Based Functional Materials: Toward a Sustainable Platform Carbon Material. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12251–12285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperandio, G.; Amoriello, T.; Carbone, K.; Fedrizzi, M.; Monteleone, A.; Tarangioli, S.; Pagano, M. Increasing the value of spent grains from craft microbreweries for energy purposes. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 58, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Husson, O.; Graber, E.; van Zwieten, L.; Taherymoosavi, S.; Thomas, T.; Nielsen, S.; Ye, J.; Pan, G.; Chia, C.; et al. The Electrochemical Properties of Biochars and How They Affect Soil Redox Properties and Processes. Agronomy 2015, 5, 322–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klüpfel, L.; Keiluweit, M.; Kleber, M.; Sander, M. Redox Properties of Plant Biomass-Derived Black Carbon (Biochar). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 5601–5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Cao, X.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Q.; Yang, F. Endogenous minerals have influences on surface electrochemistry and ion exchange properties of biochar. Chemosphere 2015, 136, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.A.; Backes, R.; Martins, C.A.; de Carvalho, C.T.; da Silva, R.A.B. Biochar: A Low-cost Electrode Modifier for Electrocatalytic, Sensitive and Selective Detection of Similar Organic Compounds. Electroanalysis 2018, 30, 2233–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinke, C.; Oliveira, P.R.; Oliveira, G.A.; Mangrich, A.S.; Marcolino-Junior, L.H.; Bergamini, M.F. Activated biochar: Preparation, characterization and electroanalytical application in an alternative strategy of nickel determination. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 983, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Zou, J.; Xiong, Q.; Peng, G.; Gao, F.; Fan, G.; Chen, S.; Lu, L. Electrochemical Sensor Based on Biochar Decorated with Gold Clusters for Sensitive Determination of Acetaminophen. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2022, 17, 220438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancelliere, R.; Carbone, K.; Pagano, M.; Cacciotti, I.; Micheli, L. Biochar from Brewers’ Spent Grain: A Green and Low-Cost Smart Material to Modify Screen-Printed Electrodes. Biosensors 2019, 9, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancelliere, R.; Di Tinno, A.; Di Lellis, A.M.; Contini, G.; Micheli, L.; Signori, E. Cost-effective and disposable label-free voltammetric immunosensor for sensitive detection of interleukin-6. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 213, 114467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancelliere, R.; Di Tinno, A.; Di Lellis, A.M.; Tedeschi, Y.; Bellucci, S.; Carbone, K.; Signori, E.; Contini, G.; Micheli, L. An inverse-designed electrochemical platform for analytical applications. Electrochem. Commun. 2020, 121, 106862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinke, C.; de Oliveira, P.R.; Bonacin, J.A.; Janegitz, B.C.; Mangrich, A.S.; Marcolino-Junior, L.H.; Bergamini, M.F. State-of-the-art and perspectives in the use of biochar for electrochemical and electroanalytical applications. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 5272–5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudicianni, P.; Ragucci, R.; Mašek, O. Controlling the conversion of biomass to biochar. In Biochar; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; pp. 2–33. ISBN 978-0-7503-2660-5. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, J.F.; Iribarren, D.; Dufour, J. Biomass Pyrolysis for Biochar or Energy Applications? A Life Cycle Assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 5195–5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.; Glaser, B.; Quicker, P. Technical, Economical, and Climate-Related Aspects of Biochar Production Technologies: A Literature Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9473–9483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashokkumar, V.; Flora, G.; Venkatkarthick, V.; Kannan, K.S.; Kuppam, C.; Stephy, G.M.; Kamyab, H.; Chen, W.-H.; Thomas, J.; Ngamcharussrivichai, C.A. dvanced technologies on the sustainable approaches for conversion of organic waste to valuable bioproducts: Emerging circular bioeconomy perspective. Fuel 2022, 324, 124313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adilla Rashidi, N.; Yusup, S.; Adilla Rashidi, N.; Yusup, S. A Mini Review of Biochar Synthesis, Characterization, and Related Standardization and Legislation. In Applications of Biochar for Environmental Safety; Abdelhafez, A.A., Abbas, M.H.H., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-78985-895-2. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Eum, P.-R.-B.; Ryu, C.; Park, Y.-K.; Jung, J.-H.; Hyun, S. Characteristics of biochar produced from slow pyrolysis of Geodae-Uksae 1. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 130, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruun, E.W.; Ambus, P.; Egsgaard, H.; Hauggaard-Nielsen, H. Effects of slow and fast pyrolysis biochar on soil C and N turnover dynamics. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 46, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, M.; Mathimani, T.; Alagumalai, A.; Chi, N.T.L.; Duc, P.A.; Bhatia, S.K.; Brindhadevi, K.; Pugazhendhi, A. A review on the pyrolysis of algal biomass for biochar and bio-oil—Bottlenecks and scope. Fuel 2021, 283, 119190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, V.; Kumar, P.S.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Sindhu, J.; Sneka, D.; Subhashini, B.; Saravanan, K.; Jeyanthi, J. Hydrothermal production of algal biochar for environmental and fertilizer applications: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1025–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, P.D.; Choi, S.W.; Igalavithana, A.D.; Yang, X.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Wang, C.-H.; Kua, H.W.; Lee, K.B.; Ok, Y.S. Sustainable gasification biochar as a high efficiency adsorbent for CO2 capture: A facile method to designer biochar fabrication. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 124, 109785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakros, J. Biochars and Their Use as Transesterification Catalysts for Biodiesel Production: A Short Review. Catalysts 2018, 8, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torri, C.; Samorì, C.; Adamiano, A.; Fabbri, D.; Faraloni, C.; Torzillo, G. Preliminary investigation on the production of fuels and bio-char from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii biomass residue after bio-hydrogen production. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 8707–8713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakou, M.; Patsalou, M.; Xiaris, N.; Tsevis, A.; Koutsokeras, L.; Constantinides, G.; Koutinas, M. Enhancing bioproduction and thermotolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via cell immobilization on biochar: Application in a citrus peel waste biorefinery. Renew. Energy 2020, 155, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavali, M.; Libardi Junior, N.; de Mohedano, R.A.; Belli Filho, P.; da Costa, R.H.R.; de Castilhos Junior, A.B. Biochar and hydrochar in the context of anaerobic digestion for a circular approach: An overview. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Rajapaksha, A.U.; Lim, J.E.; Zhang, M.; Bolan, N.; Mohan, D.; Vithanage, M.; Lee, S.S.; Ok, Y.S. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: A review. Chemosphere 2014, 99, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, F.-S.; Wu, J. Characterization and application of chars produced from pinewood pyrolysis and hydrothermal treatment. Fuel 2010, 89, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, A.; Sokołowska, Z.; Boguta, P. Biochar physicochemical properties: Pyrolysis temperature and feedstock kind effects. Rev. Environ. Sci Biotechnol 2020, 19, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demirbas, A.; Arin, G. An Overview of Biomass Pyrolysis. Energy Sources 2002, 24, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.; Pittman, C.U.; Steele, P.H. Pyrolysis of Wood/Biomass for Bio-oil: A Critical Review. Energy Fuels 2006, 20, 848–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. (Eds.) Biochar for Environmental Management; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-136-57121-3. [Google Scholar]

- Karaosmanoǧlu, F.; Işıḡıgür-Ergüdenler, A.; Sever, A. Biochar from the Straw-Stalk of Rapeseed Plant. Energy Fuels 2000, 14, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchimiya, M.; Klasson, K.T.; Wartelle, L.H.; Lima, I.M. Influence of soil properties on heavy metal sequestration by biochar amendment: 1. Copper sorption isotherms and the release of cations. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Chen, Z. Sorption of naphthalene and 1-naphthol by biochars of orange peels with different pyrolytic temperatures. Chemosphere 2009, 76, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, F.; Huang, F.; Chen, W.; Xing, B.; Zhu, L. Sorption of apolar and polar organic contaminants by waste tire rubber and its chars in single- and bi-solute systems. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeschbacher, M.; Sander, M.; Schwarzenbach, R.P. Novel electrochemical approach to assess the redox properties of humic substances. Environ. Sci. Tech. 2010, 44, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifullah; Dahlawi, S.; Naeem, A.; Rengel, Z.; Naidu, R. Biochar application for the remediation of salt-affected soils: Challenges and opportunities. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, M.K.; Bachmann, R.T.; Rafiq, M.T.; Shang, Z.; Joseph, S.; Long, R. Influence of Pyrolysis Temperature on Physico-Chemical Properties of Corn Stover (Zea mays L.) Biochar and Feasibility for Carbon Capture and Energy Balance. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, L.; Andserson, B.; Zhao, X.; Wang, D.; Ding, A. Review on utilization of biochar for metal-contaminated soil and sediment remediation. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 63, 156–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Afxentiou, N.; Fokaides, P.A. The State of the Art Overview of the Biomass Gasification Technology. Curr. Sustain. Renew. Energy Rep. 2021, 8, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinar, J.M.; Beltrán, F.J.; Ramiro, A.; González, J.F. Pyrolysis/gasification of agricultural residues by carbon dioxide in the presence of different additives: Influence of variables. Fuel Processing Technol. 1998, 55, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usevičiūtė, L.; Baltrėnaitė-Gedienė, E. Dependence of pyrolysis temperature and ligno-cellulosic physical-chemical properties of biochar on its wettability. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2021, 11, 2775–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanarella, L.; Lugato, E. The Application of Biochar in the EU: Challenges and Opportunities. Agronomy 2013, 3, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fryda, L.; Visser, R. Biochar for Soil Improvement: Evaluation of Biochar from Gasification and Slow Pyrolysis. Agriculture 2015, 5, 1076–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akhil, D.; Lakshmi, D.; Kartik, A.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Arun, J.; Gopinath, K.P. Production, characterization, activation and environmental applications of engineered biochar: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 2261–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.; Tsubota, T.; Hassan, M.A.; Andou, Y. Surface Functionalization of Biochar from Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch through Hydrothermal Process. Processes 2021, 9, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, T.; Condron, L.; Kammann, C.; Müller, C. A Review of Biochar and Soil Nitrogen Dynamics. Agronomy 2013, 3, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sakhiya, A.K.; Anand, A.; Kaushal, P. Production, activation, and applications of biochar in recent times. Biochar 2020, 2, 253–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołtowski, M.; Charmas, B.; Skubiszewska-Zięba, J.; Oleszczuk, P. Effect of biochar activation by different methods on toxicity of soil contaminated by industrial activity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 136, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghdi, M.; Taheran, M.; Brar, S.K.; Rouissi, T.; Verma, M.; Surampalli, R.Y.; Valero, J.R. A green method for production of nanobiochar by ball milling- optimization and characterization. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 1394–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peterson, S.C.; Jackson, M.A.; Kim, S.; Palmquist, D.E. Increasing biochar surface area: Optimization of ball milling parameters. Powder Technol. 2012, 228, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, B.; Chen, W.-Y.; Mattern, D.L.; Hammer, N.; Dorris, A. Low-temperature acoustic-based activation of biochar for enhanced removal of heavy metals. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 34, 101166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buates, J.; Imai, T. Biochar functionalization with layered double hydroxides composites: Preparation, characterization, and application for effective phosphate removal. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 37, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosa, A.; El-Ghamry, A.; Tolba, M. Functionalized biochar derived from heavy metal rich feedstock: Phosphate recovery and reusing the exhausted biochar as an enriched soil amendment. Chemosphere 2018, 198, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalina, F.; Razak, A.S.A.; Krishnan, S.; Zularisam, A.W.; Nasrullah, M. A comprehensive assessment of the method for producing biochar, its characterization, stability, and potential applications in regenerative economic sustainability—A review. Clean. Mater. 2022, 3, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, B.; Broome, J.W.; Chen, W.Y.; Mattern, D.L.; Egiebor, N.O.; Hammer, N.; Smith, C.L. Urea functionalization of ultrasound-treated biochar: A feasible strategy for enhancing heavy metal adsorption capacity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 51, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saletnik, B.; Zaguła, G.; Bajcar, M.; Tarapatskyy, M.; Bobula, G.; Puchalski, C. Biochar as a Multifunctional Component of the Environment—A Review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joseph, S.D.; Camps-Arbestain, M.; Lin, Y.; Munroe, P.; Chia, C.H.; Hook, J.; van Zwieten, L.; Kimber, S.; Cowie, A.; Singh, B.P.; et al. An investigation into the reactions of biochar in soil. Aust. J. Soil Res. 2010, 48, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Graber, E.; Chia, C.; Munroe, P.; Donne, S.; Thomas, T.; Nielsen, S.; Marjo, C.; Rutlidge, H.; Pan, G.; et al. Shifting paradigms: Development of high-efficiency biochar fertilizers based on nano-structures and soluble components. Carbon Manag. 2013, 4, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cayuela, M.L.; van Zwieten, L.; Singh, B.P.; Jeffery, S.; Roig, A.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A. Biochar’s role in mitigating soil nitrous oxide emissions: A review and meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 191, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, F.J.; Cayuela, M.L.; Roig, A.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A. Understanding, measuring and tuning the electrochemical properties of biochar for environmental applications. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2017, 16, 695–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Rotaru, A.-E.; Shrestha, P.M.; Malvankar, N.S.; Liu, F.; Fan, W.; Nevin, K.P.; Lovley, D.R. Promoting Interspecies Electron Transfer with Biochar. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fang, G.; Liu, C.; Gao, J.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Zhou, D. Manipulation of Persistent Free Radicals in Biochar To Activate Persulfate for Contaminant Degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 5645–5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Yuan, Y.; Tang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, S. Biochar as an electron shuttle for reductive dechlorination of pentachlorophenol by Geobacter sulfurreducens. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, T.; Levin, B.D.A.; Guzman, J.J.L.; Enders, A.; Muller, D.A.; Angenent, L.T.; Lehmann, J. Rapid electron transfer by the carbon matrix in natural pyrogenic carbon. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, N.; Xiao, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D. Characterization of biochars derived from different materials and their effects on microbial dechlorination of pentachlorophenol in a consortium. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, B.T.; Dinh, G.D.; Dong, H.P.; Le, L.B. Sodium adsorption isotherm and characterization of biochars produced from various agricultural biomass wastes. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 346, 131250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduini, F.; Micheli, L.; Scognamiglio, V.; Mazzaracchio, V.; Moscone, D. Sustainable materials for the design of forefront printed (bio)sensors applied in agrifood sector. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 128, 115909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suguihiro, T.M.; de Oliveira, P.R.; de Rezende, E.I.P.; Mangrich, A.S.; Marcolino Junior, L.H.; Bergamini, M.F. An electroanalytical approach for evaluation of biochar adsorption characteristics and its application for Lead and Cadmium determination. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 143, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Oliveira, P.R.; Lamy-Mendes, A.C.; Gogola, J.L.; Mangrich, A.S.; Marcolino Junior, L.H.; Bergamini, M.F. Mercury nanodroplets supported at biochar for electrochemical determination of zinc ions using a carbon paste electrode. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 151, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustini, D.; Mangrich, A.S.; Bergamini, M.F.; Marcolino-Junior, L.H. Sensitive voltammetric determination of lead released from ceramic dishes by using of bismuth nanostructures anchored on biochar. Talanta 2015, 142, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.R.; Lamy-Mendes, A.C.; Rezende, E.I.P.; Mangrich, A.S.; Marcolino Junior, L.H.; Bergamini, M.F. Electrochemical determination of copper ions in spirit drinks using carbon paste electrode modified with biochar. Food Chem. 2015, 171, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalinke, C.; Mangrich, A.S.; Marcolino-Junior, L.H.; Bergamini, M.F. Carbon Paste Electrode Modified with Biochar for Sensitive Electrochemical Determination of Paraquat. Electroanalysis 2016, 28, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.R.; Kalinke, C.; Mangrich, A.S.; Marcolino-Junior, L.H.; Bergamini, M.F. Copper hexacyanoferrate nanoparticles supported on biochar for amperometric determination of isoniazid. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 285, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, P.R.; Kalinke, C.; Gogola, J.L.; Mangrich, A.S.; Junior, L.H.M.; Bergamini, M.F. The use of activated biochar for development of a sensitive electrochemical sensor for determination of methyl parathion. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017, 799, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; He, L.; Liu, Y.; Piao, Y. Preparation of highly conductive biochar nanoparticles for rapid and sensitive detection of 17β-estradiol in water. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 292, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Ma, H.; Ren, H.; Shi, Y.; Han, Y.; Ye, B.-C. Electrochemical sensing platform based on the biomass-derived microporous carbons for simultaneous determination of ascorbic acid, dopamine, and uric acid. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 121, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yan, Y.; Cao, D.; Wang, G. Nanoporous carbon derived from dandelion pappus as an enhanced electrode material with low cost for amperometric detection of tryptophan. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2018, 818, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, L.; Wen, Y.; Yang, G.; Liu, G.; Yi, Y.; Shang, Q.; Yang, X.; Cai, S. Voltammetric Analysis of Thiamethoxam Based on Inexpensive Thick-Walled Moso Bamboo Biochar Nanocomposites. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2019, 14, 10848–10861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’Anna, M.V.S.; Carvalho, S.W.M.M.; Gevaerd, A.; Silva, J.O.S.; Santos, E.; Carregosa, I.S.C.; Wisniewski, A.; Marcolino-Junior, L.H.; Bergamini, M.F.; Sussuchi, E.M. Electrochemical sensor based on biochar and reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite for carbendazim determination. Talanta 2020, 220, 121334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinke, C.; Zanicoski-Moscardi, A.P.; de Oliveira, P.R.; Mangrich, A.S.; Marcolino-Junior, L.H.; Bergamini, M.F. Simple and low-cost sensor based on activated biochar for the stripping voltammetric detection of caffeic acid. Microchem. J. 2020, 159, 105380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinke, C.; Wosgrau, V.; Oliveira, P.R.; Oliveira, G.A.; Martins, G.; Mangrich, A.S.; Bergamini, M.F.; Marcolino-Junior, L.H. Green method for glucose determination using microfluidic device with a non-enzymatic sensor based on nickel oxyhydroxide supported at activated biochar. Talanta 2019, 200, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalechume, C.; Mageswari, G.; Swamidoss, C.M.A. Determination of dopamine in the presence of ascorbic acid using polyaniline/carbon dot composites. Mater. Today Proc. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yao, L.; He, L.; Liu, N.; Piao, Y. Electrochemical Enzyme Biosensor Bearing Biochar Nanoparticle as Signal Enhancer for Bisphenol A Detection in Water. Sensors 2019, 19, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shan, R.; Shi, Y.; Gu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, H. Single and competitive adsorption affinity of heavy metals toward peanut shell-derived biochar and its mechanisms in aqueous systems. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, X.; Zhuang, X.; Li, B.; Xu, X.; Wei, Z.; Song, Y.; Jiang, E. Comparison of characterization and adsorption of biochars produced from hydrothermal carbonization and pyrolysis. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2018, 10, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shao, J.; Wang, X.; Deng, Y.; Yang, H.; Chen, H. Characterization of Modified Biochars Derived from Bamboo Pyrolysis and Their Utilization for Target Component (Furfural) Adsorption. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 5119–5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, A.Z.; Sudo, S.; Akiyama, H.; Win, K.T.; Shibata, A.; Yamamoto, A.; Sano, T.; Hirono, Y. Effect of dolomite and biochar addition on N2O and CO2 emissions from acidic tea field soil. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, L.; Yang, Y.; Kim, J.; Yao, L.; Dong, X.; Li, T.; Piao, Y. Multi-layered enzyme coating on highly conductive magnetic biochar nanoparticles for bisphenol A sensing in water. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 384, 123276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhan, A.; Muthukumarappan, K.; Wei, L.; Qiao, Q.; Rahman, M.T.; Ghimire, N. Development and characterization of a novel activated biochar-based polymer composite for biosensors. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2021, 26, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Guo, M.; Wu, S.; Fornara, D.; Sarkar, B.; Sun, L.; Wang, H. Electrochemical sensor based on corncob biochar layer supported chitosan-MIPs for determination of dibutyl phthalate (DBP). J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 897, 115549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinke, C.; Oliveira, P.R.; Bonet San Emeterio, M.; González-Calabuig, A.; Valle, M.; Salvio Mangrich, A.; Humberto Marcolino Junior, L.; Bergamini, M.F. Voltammetric Electronic Tongue Based on Carbon Paste Electrodes Modified with Biochar for Phenolic Compounds Stripping Detection. Electroanalysis 2019, 31, 2238–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, G.; Gogola, J.L.; Caetano, F.R.; Kalinke, C.; Jorge, T.R.; Santos, C.N.D.; Bergamini, M.F.; Marcolino-Junior, L.H. Quick electrochemical immunoassay for hantavirus detection based on biochar platform. Talanta 2019, 204, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Sun, M.; Bo, X.; Wang, H.-L.; Zhou, M. Amperometric ascorbic acid biosensor based on carbon nanoplatelets derived from ground cherry husks. Electrochem. Commun. 2017, 82, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, J.M.; Jeon, Y.; Lee, J.; Oh, J.; Hooch Antink, W.; Kim, D.; Piao, Y. Novel two-step activation of biomass-derived carbon for highly sensitive electrochemical determination of acetaminophen. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 259, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhu, R.; Karuppiah, C.; Chen, S.-M.; Veerakumar, P.; Liu, S.-B. Electrochemical detection of 4-nitrophenol based on biomass derived activated carbons. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 5274–5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeramani, V.; Sivakumar, M.; Chen, S.-M.; Madhu, R.; Alamri, H.R.; Alothman, Z.A.; Hossain, S.A.; Chen, C.-K.; Yamauchi, Y.; Miyamoto, N.; et al. Lignocellulosic biomass-derived, graphene sheet-like porous activated carbon for electrochemical supercapacitor and catechin sensing. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 45668–45675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veerakumar, P.; Sangili, A.; Chen, S.-M.; Pandikumar, A.; Lin, K.-C. Fabrication of Platinum–Rhenium Nanoparticle-Decorated Porous Carbons: Voltammetric Sensing of Furazolidone. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 3591–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeramani, V.; Madhu, R.; Chen, S.-M.; Veerakumar, P.; Syu, J.-J.; Liu, S.-B. Cajeput tree bark derived activated carbon for the practical electrochemical detection of vanillin. New J. Chem. 2015, 39, 9109–9115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, K.; Chen, L.; Huang, Z.; Liu, G.; Li, M.; Wen, Y. Mass preparation of micro/nano-powders of biochar with water-dispersibility and their potential application. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 9649–9657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Gao, S.; Lai, C.; He, H.; Han, F.; Pan, X. Biochar enhanced microbial degradation of 17β-estradiol. Environ. Sci. Processes Impacts 2019, 21, 1736–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadifiyine, S.; Haddam, M.; Mandli, J.; Chadel, S.; Blanchard, C.C.; Marty, J.L.; Amine, A. Amperometric Biosensor Based on Tyrosinase Immobilized on to a Carbon Black Paste Electrode for Phenol Determination in Olive Oil. Anal. Lett. 2013, 46, 2705–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfragano, P.S.; Laschi, S.; Renai, L.; Fichera, M.; Del Bubba, M.; Palchetti, I. Electrochemical sensors based on sewage sludge–derived biochar for the analysis of anthocyanins in berry fruits. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, E.; Alexander, R.; Francis, P.S.; Guijt, R.M.; Barbante, G.J.; Doeven, E.H. A Comparison of Commercially Available Screen-Printed Electrodes for Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence Applications. Front. Chem. 2021, 8, 628483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancelliere, R.; Tinno, A.D.; Cataldo, A.; Bellucci, S.; Micheli, L. Powerful Electron-Transfer Screen-Printed Platforms as Biosensing Tools: The Case of Uric Acid Biosensor. Biosensors 2021, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tinno, A.; Cancelliere, R.; Mantegazza, P.; Cataldo, A.; Paddubskaya, A.; Ferrigno, L.; Kuzhir, P.; Maksimenko, S.; Shuba, M.; Maffucci, A.; et al. Sensitive Detection of Industrial Pollutants Using Modified Electrochemical Platforms. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasirekha, N.; Chen, Y.W. Carbonaceous Nanomaterials for Environmental Remediation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, Q.U.A.; Silveri, F.; Della Pelle, F.; Scroccarello, A.; Zappi, D.; Cozzoni, E.; Compagnone, D. Water-Phase Exfoliated Biochar Nanofibers from Eucalyptus Scraps for Electrode Modification and Conductive Film Fabrication. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 13988–13998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagdale, P.; Ziegler, D.; Rovere, M.; Tulliani, J.; Tagliaferro, A. Waste Coffee Ground Biochar: A Material for Humidity Sensors. Sensors 2019, 19, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, X.; Lu, K.; Lin, D.; Li, Y.; Yin, S.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, M.; Chen, G. Hierarchical Porous Tubular Biochar Based Sensor for Detection of Trace Lead (II). Electroanalysis 2021, 33, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, D.; Palmero, P.; Giorcelli, M.; Tagliaferro, A.; Tulliani, J.-M. Biochars as Innovative Humidity Sensing Materials. Chemosensors 2017, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scroccarello, A.; Pelle, F.D.; Bukhari, Q.U.A.; Silveri, F.; Zappi, D.; Cozzoni, E.; Compagnone, D. Eucalyptus Biochar as a Sustainable Nanomaterial for Electrochemical Sensors. Chem. Proc. 2021, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S.; Sivam, S.; Elancheziyan, M.; Senthilkumar, S.; Ramakrishan, S.G.; Soundappan, T.; Ponnusamy, V.K. Novel delipidated chicken feather waste-derived carbon-based molybdenum oxide nanocomposite as efficient electrocatalyst for rapid detection of hydroquinone and catechol in environmental waters. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 293, 118556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappi, D.; Varani, G.; Cozzoni, E.; Iatsunskyi, I.; Laschi, S.; Giardi, M.T. Innovative Eco-Friendly Conductive Ink Based on Carbonized Lignin for the Production of Flexible and Stretchable Bio-Sensors. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Ge, Y.; He, S.; Ge, F.; Huang, Q.; Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wen, Y.; Wang, B. Development of New Electrochemical Sensor based on Kudzu Vine Biochar Modified Flexible Carbon Electrode for Portable Wireless Intelligent Analysis of Clenbuterol. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2020, 15, 7326–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikhil; Srivastava, S.K.; Srivastava, A.; Srivastava, M.; Prakash, R. Electrochemical Sensing of Roxarsone on Natural Biomass-Derived Two-Dimensional Carbon Material as Promising Electrode Material. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 2908–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahammad, A.J.S.; Pal, P.R.; Shah, S.S.; Islam, T.; Hasan, M.; Qasem, M.A.A.; Odhikari, N.; Sarker, S.; Kim, D.M.; Aziz, A. Activated jute carbon paste screen-printed FTO electrodes for nonenzymatic amperometric determination of nitrite. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 832, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, D.; Boschetto, F.; Marin, E.; Palmero, P.; Pezzotti, G.; Tulliani, J.-M. Rice husk ash as a new humidity sensing material and its aging behavior. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 328, 129049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espro, C.; Satira, A.; Mauriello, F.; Anajafi, Z.; Moulaee, K.; Iannazzo, D.; Neri, G. Orange peels-derived hydrochar for chemical sensing applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 341, 130016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangili, A.; Veerakumar, P.; Chen, S.-M.; Rajkumar, C.; Lin, K.-C. Voltammetric determination of vitamin B2 by using a highly porous carbon electrode modified with palladium-copper nanoparticles. Microchim. Acta 2019, 186, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elancheziyan, M.; Ganesan, S.; Theyagarajan, K.; Duraisamy, M.; Thenmozhi, K.; Weng, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-T.; Ponnusamy, V.K. Novel biomass-derived porous-graphitic carbon coated iron oxide nanocomposite as an efficient electrocatalyst for the sensitive detection of rutin (vitamin P) in food and environmental samples. Environ. Res. 2022, 211, 113012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, M.E.; Khalifa, M.A.; El Wakeel, Y.M.; Header, M.S.; El-Sharkawy, R.M.; Kumar, S.; Abdel-Fattah, T.M. A novel nanocomposite of Liquidambar styraciflua fruit biochar-crosslinked-nanosilica for uranyl removal from water. Bioresour Technol. 2019, 278, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afify, A.S.; Ahmad, S.; Khushnood, R.A.; Jagdale, P.; Tulliani, J.-M. Elaboration and characterization of novel humidity sensor based on micro-carbonized bamboo particles. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 239, 1251–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Process | Temperature | Time | Solid (Biochar) | Liquid (Bio-Oil) | Gas (Syngas) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast pyrolysis | Mild (≈500 °C) | <2 s | 12% | 75% (25% H2O) | 13% |

| Intermediate Pyrolysis | Mild | Moderate | 25% | 50% (50% H2O) | 25% |

| Slow Pyrolysis | Mild/low | Long | 35% | 30% (70% H2O) | 35% |

| Gasification | High (>800 °C) | Long | 10% | 5% (tar + H2O) | 85% |

| Parameter | European Biochar Certificate V4.8 | IBI Biochar Standards V2.0 |

|---|---|---|

| C content | Required (total C) Biochar ≥ 50% PCM < 50% | Required (organic C) 10% Minimum Class 1: ≥60% Class 2: ≥30% and <60% Class 3: ≥10% and <30% |

| Molar H/Corg ratio | Required 0.7 maximum (molar ratio) | Required 0.7 maximum (molar ratio) |

| Total Ash | Required | Required |

| Molar O/C ratio | Required 0.4 maximum | Not required |

| Macronutrients (NPK) | Required (Total N) Required (Total P, K, Mg, Ca) | Required (Total N) Optional (Total P and K) |

| Heavy metals, metalloids and other elements | Required Metals: Pb, Cd, Cu, Ni, Hg, Zn, Cr Basic grade: Pb < 150 mg kg−1 Cd < 1.5 mg kg−1 Cu < 100 mg kg−1 Ni < 50 mg kg−1 Hg < mg kg−1 Zn < 400 mg kg−1 Cr < 90 mg kg−1 Premium grade: Pb < 120 mg kg−1 Cd < 1 mg kg−1 Cu < 100 mg kg−1 Ni < 30 mg kg−1 Hg < 1 mg kg−1 Zn < 400 mg kg−1 Cr < 80 mg kg−1 | Required Metals: Pb, Cd, Cu, Ni, Hg, Zn, Cr, Co, Mo Metalloids: B, As, Se Others: Cl, Na Maximum Allowed Thresholds: As 12–100 mg kg−1 Cd 1.4–39 mg kg−1 Cr 64–1200 mg kg−1 Co 40–150 mg kg−1 Cu 63–1500 mg kg−1 Pb 70–500 mg kg−1 Hg 1–17 mg kg−1 Mo 5–20 mg kg−1 Ni 47–600 mg kg−1 Se 2–36 mg kg−1 Zn 200–7000 mg kg−1 B Declaration Cl Declaration Na Declaration |

| PAHs | Required Basic grade: <12 mg kg−1 Premium grade: <4 mg kg−1 | Required 6–300 mg kg−1 |

| PCBs | Required <0.2 mg kg−1 | Required 0.2–0.5 mg kg−1 |

| PCDD/Fs | Required <20 ng kg−1 | Required <17 ng kg−1 |

| Volatile Matter | Required (Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)) | Optional (Volatile matter) |

| Electrical conductivity | Required | Required |

| pH | Required | Required |

| Bulk density | Required | Not required |

| Particle size distribution | Not required | Required |

| Water content | Required (water content) | Required (Moisture content) |

| Surface area | Required (Specific surface area) | Optional (Total surface area and external surface area) |

| Germination inhibition | Not required | Required |

| Feedstock | Electrode | Analyte | LOD (nM) | Linear Range (M) | Real Sample Matrix | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castor oil cake | Biochar-CPE | Cd Pb | 69 (Cd) 9.8 (Pb) | (0.03–5.0) × 10−5 (0.001–5.0) × 10−5 | wastewater | [95] |

| Castor oil cake | HgND-Biochar-CPE | Zn | 170 | (0.07–3) × 10−5 | collyrium and ointment | [96] |

| Castor oil cake | Bi-nano-Biochar- CPE | Pb | 1.41 | (0.005–1) × 10−3 | Overglaze decorated ceramic dishes | [97] |

| Castor oil cake | Biochar-CPE | Cu | 400 | (0.1–3.1) × 10−5 | Vodka, cachaça, gin and tequila | [98] |

| Castor oil cake | Sbmicro-Biochar- CPE | Paraquat | 34 | (0.03–1.0) × 10−6 | natural water coconut water | [99] |

| Castor oil cake | Biochar-CPE | Isoniazid | 63 | (0.1–1.0) × 10−5 | Synthetic human urine | [100] |

| Castor oil cake | Biochar-CPE | Methyl Parathion | 39 | (0.01–170) × 10−6 | Drinking water and fruit juices | [101] |

| Sugarcane bagasse | BioNano-GCE | 17 β- estradiol | 11.3 | (0.05–20) × 10−6 | Groundwater | [102] |

| Kiwi skin | ZnCl2/Biochar GCE | AA Dopamine UA | 20 160 110 | (0.05–200) × 10−6 (2–2000) × 10−6 (1–2500) × 10−6 | Human urine | [103] |

| Dandelion pappus | Npc/GCE | Try | 30 | (1–103) × 10−6 | Commercial amino acid injection and Fetal calf serum | [104] |

| Bamboo | BioNC-GCE | Tmx | 220 | (0.5–35) × 10−7 | Spinach, Rice, Pear, Red soil, Tap water, Farmland water, River water, Lake water | [105] |

| Water Hyacinth | Biochar-rGO- CPE | Cbz | 2.3 | (30–900) × 10−8 | Orange juice, Lettuce leaves, Drinking water, Wastewater | [106] |

| Castor oil cake | Ac-biochar-CPE | Caffeic acid | 30.9 | (1.0–3000) × 10−6 | White, Rose and Red wine | [107] |

| Castor oil cake | Ni/biochar-CPE | Glucose | 137 | (5–100) × 10−6 | Human saliva Blood serum | [108] |

| Pumpkin stems | Biochar-GCE | AA Dopamine UA | 2300 30 510 | (30–95) × 10−6 (1–65) × 10−6 (2–230) × 10−6 | SH and Human blood serum | [109] |

| Bamboo fungus | Biochar-GCE | Bis-A | 1068 | (0.02–10) × 10−6 | Groundwater | [110] |

| Kelp | Act-biochar-GCE | Acp | 4 | (2.5–2000) × 10−6 | Human serum And Medical tablet | [111] |

| Biosensor | Source | LOD (μM) | Analyte | Linear Range (M) | Real Samples | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biochar-GCE | Waste amla fruits | 100 | AA | (0.01–3.57) × 10−6 | MI dose and soft drink | [120] |

| ZnCl2 + KOH-Biochar-GCE | Kelp (algae) | 0.004 | Acp | (0.01–20) × 10−6 | Human urine | [121] |

| Biochar-GCE | Mango leaves | 0.16 | p-NP | (1–500) × 10−6 | Tap water and orange juice | [122] |

| Biochar-GCNS | BSF | 0.67 | Catechin | (4–368) × 10−6 | Green tea | [123] |

| Pt-Re NPs-BC/GCE | Cassia fistula fruit | 0.076 | FRZ | (0.1–300) × 10−6 | Human blood, serum and urine | [124] |

| Biochar-GCE | Cajeput tree bark | 0.68 | Vanillin | (5–1150) × 10−6 | Chocolate and Biscuit | |

| Biochar-CPE | Castor oil cake | 0.031 | Caffeic Acid | (1.0–3000) × 10−6 | White, Rose and Red wine | [125] |

| Nanop-Biochar-GCE | Pitch Pine | 0.007 | Pb2+ | (1.5–850) × 10−8 (5.0–850) × 10−8 | Chinese cabbage and Navel orange | [126] |

| Biochar NPs-GCE | Bagasse | 0.011 | 17-β-estradiol | (0.05–20) × 10−6 | Groundwater | [127] |

| MIP-DBP-CTS/F-CC3/GCE | Corncob | 0.003 | Dibutyl Phthalate | (0.5–1.8) × 10−6 | Rice and Wine | [128] |

| BCNP/Tyr/Nafion/GCE | Sugarcane | 0.003 | Bisphenol A | (0.02–10) × 10−6 | Groundwater | [115] |

| CBPE-Tyr/SP CBPE | Beer | 0.003 | Phenolic Compounds | (0.013–150) × 10−6 | Olive oil | [129] |

| Sensor | Source | Analyte | LOD (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nanoF-biochar-SPE | Eucalyptus scraps | o-diphenols m-phenols | 0.6 3.8 | [134] |

| PVB/biochar-SPE | Waste coffee ground | Humidity | 20 RH% | [135] |

| Tub-biochar-SPE | Peachwood | Lead ions | 0.02 | [136] |

| Ty-biochar-SPE | BSG | Catecholamine | 20 | [34] |

| PVP-biochar-SPE | Conifer and rapeseed pellets | Humidity | 5 RH% | [137] |

| Inverse-designed SPE | BSG | Potassium ferricyanide, AA, hexaammine ruthenium(III) chloride and NADH | 3 3 9 12 | [138] |

| Cnf-biochar-SPE | Eucalyptus scraps | Hydroxytyrosol (o-diphenol) and tyrosol (m-phenol) | ≤0.5 ≤3.8 | [139] |

| cMbOx-biochar-SPE | Chicken feather waste | HydroquinoneCatechol | 0.063 0.059 | [140] |

| Laccase-carboLign-SPE | Eucalyptus globulus | Catechol | 2.01 | [141] |

| Biochar-SPE | Kudzu vine | Clenbuterol | 0.75 | [142] |

| SPE/2D activated carbon | Desmostachya bipinnata | Roxarsone | 1.5 | [143] |

| Fdop-Ac-biochar-SPE | Corchorus genus (jute) | Nitrite | 0.05 | [144] |

| Biochar-SPE | Rice husk ash | Humidity | 15% RH | [145] |

| SPE/hydrochar | Orange peels waste | Dopamine | 0.2 | [146] |

| nanoPd-Cu-Ac-biochar-SPE | Pistachio nutshells | Riboflavin | 0.0008 | [147] |

| nanoGF-Ac-biochar-nanoFeOx-SPE | Tamarind fruit shells | Rutin | 0.027 | [148] |

| Biochar-SPE | Bamboo | Humidity | 10% RH | [149] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cancelliere, R.; Cianciaruso, M.; Carbone, K.; Micheli, L. Biochar: A Sustainable Alternative in the Development of Electrochemical Printed Platforms. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors10080344

Cancelliere R, Cianciaruso M, Carbone K, Micheli L. Biochar: A Sustainable Alternative in the Development of Electrochemical Printed Platforms. Chemosensors. 2022; 10(8):344. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors10080344

Chicago/Turabian StyleCancelliere, Rocco, Miriam Cianciaruso, Katya Carbone, and Laura Micheli. 2022. "Biochar: A Sustainable Alternative in the Development of Electrochemical Printed Platforms" Chemosensors 10, no. 8: 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors10080344

APA StyleCancelliere, R., Cianciaruso, M., Carbone, K., & Micheli, L. (2022). Biochar: A Sustainable Alternative in the Development of Electrochemical Printed Platforms. Chemosensors, 10(8), 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors10080344