Review on Sensing Applications of Perovskite Nanomaterials

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Structure, Stability and Properties of Perovskites

3. Factors Affecting Sensor Interrogations of Perovskite Nanomaterials

- A.

- Suitable nanostructure: Design and development of suitable nanostructure for a specified analyte/sensor utility is still a question to researchers. Since perovskites may form diverse nanostructures such as quantum dots, nanocrystals, nanowires/rods, nanoparticles, etc. It is still the most difficult challenge for scholars to identify the proper perovskite nanomaterials for their target sensor investigation. Another critical issue is that some synthetic path may lead to a mixture of nanostructures, hence an improved strategy or synthetic path is required to afford explicit nanostructured materials.

- B.

- Stability: perovskite nanomaterials has the major issue of stability, which might influence many sensor responses. For example, organometallic halide perovskites can be significantly affected by moisture and humid conditions. Likewise, both oxide and halide perovskites can become unstable by temperature, pressure and solvent environment [67]. However, this property may also direct the perovskite materials toward sensors for pressure, temperature, solvents, etc. [68,69,70]. These factors might disrupt their crystallinity, structure and morphology, hence sensory designs for other analytes require precautions. Due to the stability concern, recycle of perovskite nanomaterials is still an open question in electronic device-based sensors.

- C.

- Toxicity/environmental affordability: to authenticate the sensor efficacies of perovskite nanomaterials, elucidation of their toxicity or environmental affordability is much anticipated. Toxicity measurements may tell us the biocompatibility of those materials to be consumed in healthcare products. However, majority of halide perovskites are likely to be toxic, hence their use in biosamples are rather restricted. For example, CH3NH3PbX3 (X = Cl, Br and I) are well known candidates with good emissive nature but should be avoided to use in biosamples. Bio/environmental samples may be affected by the presence of toxic Pb ions, hence actions are needed to eliminate their harmfulness via suitable modifications with appropriate capping or cations [71].

- D.

- Quantum yield (Φ): consumption of luminescent perovskite nanomaterials-based analyte detection is becoming the modern research topic. However, developing such luminescent materials with analyte specificity is still a challenge. Since luminescent property may vary at diverse precursor dilution [72], it is very essential to develop materials with high quantum yield (Φ) values. For example, Zhu et al. publicized the CsPbBr3 perovskite nanocrystals with 87% quantum yield towards colorimetric sensing of peroxide number in edible oils [73]. Therefore, the development of luminescent perovskite nanomaterials with high quantum yield is expected for sensor studies.

4. Sensing Utilities of Metal Oxide Perovskite Nanomaterials

5. Metal Halide Perovskites in Analyte Detection

6. Perovskites Incorporated Nanocomposites as Sensors

7. Advantages and Limitations

- The excellent opto-electronic properties of both metal oxide and metal halide/organometallic halide perovskites allow their usage in device-based analyte detection, especially towards energetic/toxic gases and humidity quantitation.

- Luminescent characteristics of metal halide/organometallic halide quantum dots or nanocrystals have advantages over PL-based identification of specific target. Their metallic and crystalline nature further improve their sensitivity in comparison with carbon dots [210].

- Selectivity and sensitivity of both perovskites can be improved towards practical reliability with precision when modified or combined with nanostructured materials, such as MIPs.

- A suitable modification of operational electrodes with perovskite materials could extend their usage in diverse analyte assays.

- Majority of metal oxide perovskite-based devices operate at high temperatures in the assay of gases, which becomes a disadvantage in many cases. Likewise, thin film-based sensory performance is limited by film thickness, thereby careful optimization is necessary.

- Environment and solvent conditions are the major threats to the perovskite-facilitated sensory investigations, except in the humidity analysis.

- Cost-effectiveness in the design of perovskite-based devices is still a concern for the researchers.

- Due to the material toxicity and instability in certain circumstances, perovskite sensors have limits in reliability and toxicity. Therefore, unlike the carbon-based materials [211], it still remains an important challenge to apply them in biological and clinical diagnosis.

- For fluorescent-based assays, development of suitable perovskite material with high PLQY is limited by synthetic tactics, stabilizer ligands, temperature, etc.

8. Conclusions and Perspectives

- The underlying mechanisms in many sensory reports still require in-depth investigations with respect to theoretical concepts.

- There are only limited reports on the fluorescent-based analyte assays using metal oxide perovskites, thereby need more attention.

- The majority of the device-based sensory investigations are influenced by operational temperature, therefore, considerate optimization is needed to attain responses at room temperature.

- A cost-effective, reproducible and standardized procedure is required to produce “state of the art” materials towards specific target (toxic gases, VOCs, anions, cations and physical parameters) for commercialization.

- There are only limited reports on the studies of perovskite nanowire-based chemo-/biosensors, hence more efforts need to be devoted in this research area.

- Perovskite nanomaterial-mediated sensing of biologically important species must be promoted with real applications.

- Focus on lead free organometallic halide perovskites is desirable for research in biological imaging studies.

- Research in the development of stable perovskite nanomaterials for environmental and biological assays needs to be intensively stimulated and encouraged.

- Investigations on the incorporation of well-known matrixes in perovskite-composite sensors, such as metal organic frameworks, metal nanostructures, hybrid clusters and polymers, need more attention.

- Perovskite nanomaterial-based colorimetric/naked eye analyte determinations require further attention.

- Design and development of low toxic perovskite nanomaterial-based devices/probes towards sensing-drug delivery modules are required to be established in the future.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, A.; Chatterjee, S. Nanomaterials based electrochemical sensors for biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5425–5438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosposito, P.; Burratti, L.; Venditti, I. Silver Nanoparticles as Colorimetric Sensors for Water Pollutants. Chemosensors 2020, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- BelBruno, J.J. Nanomaterials in Sensors. Nanomaterials 2013, 3, 572–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shellaiah, M.; Sun, K.W. Review on Nanomaterial-Based Melamine Detection. Chemosensors 2019, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chansuvarn, W.; Tuntulani, T.; Imyim, A. Colorimetric detection of mercury (II) based on gold nanoparticles, fluorescent gold nanoclusters and other gold-based nanomaterials. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2015, 65, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Akiba, U.; Anzai, J.-I. Recent Progress in Nanomaterial-Based Electrochemical Biosensors for Cancer Biomarkers: A Review. Molecules 2017, 22, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shellaiah, M.; Sun, K.W. Luminescent Metal Nanoclusters for Potential Chemosensor Applications. Chemosensors 2017, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeng, S.; Baillargeat, D.; Ho, H.-P.; Yong, K.-T. Nanomaterials enhanced surface plasmon resonance for biological and chemical sensing applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 3426–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Eperon, G.E.; Snaith, H.J. Metal halide perovskites for energy applications. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Grätzel, M.; Nazeeruddin, M.K. Organohalide lead perovskites for photovoltaic applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2448–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.J.; Billinge, S.J.L. Perovskites at the nanoscale: From fundamentals to applications. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 6206–6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labhasetwar, N.; Saravanan, G.; Kumar Megarajan, S.; Manwar, N.; Khobragade, R.; Doggali, P.; Grasset, F. Perovskite-type catalytic materials for environmental applications. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2015, 16, 036002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhu, K. Organic–inorganic hybrid lead halide perovskites for optoelectronic and electronic applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 655–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adjokatse, S.; Fang, H.-H.; Loi, M.A. Broadly tunable metal halide perovskites for solid-state light-emission applications. Mater. Today 2017, 20, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, K.P.; Ellingson, R.J. 11—An Overview of Hybrid Organic–Inorganic Metal Halide Perovskite Solar Cells. In A Comprehensive Guide to Solar Energy Systems; Letcher, T.M., Fthenakis, V.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 233–254. [Google Scholar]

- Assirey, E.A.R. Perovskite synthesis, properties and their related biochemical and industrial application. Saudi Pharmaceut. J. 2019, 27, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, H.; Yan, H. Large-area perovskite solar cells—A review of recent progress and issues. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 10489–10508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hong, K.; Le, Q.V.; Kim, S.Y.; Jang, H.W. Low-dimensional halide perovskites: Review and issues. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 2189–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rørvik, P.M.; Grande, T.; Einarsrud, M.-A. One-Dimensional Nanostructures of Ferroelectric Perovskites. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 4007–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, K.; Khan, S.A.; Shabbir, B.; Zhang, Y.; Khan, Q.; Bao, Q. Synthesis and optical applications of low dimensional metal-halide perovskites. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 152002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, J.W. Perovskite oxides for semiconductor-based gas sensors. Sens. Actuators B 2007, 123, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; He, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, H. CH3NH3Br solution as a novel platform for the selective fluorescence detection of Pb2+ ions. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varignon, J.; Bibes, M.; Zunger, A. Origin of band gaps in 3d perovskite oxides. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; Qin, Z.; Zeng, D.; Xie, C. Metal-oxide-semiconductor based gas sensors: Screening, preparation, and integration. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 6313–6329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Qin, H.; Sun, L.; Hu, J. CO2 sensing properties and mechanism of nanocrystalline LaFeO3 sensor. Sens. Actuators B 2013, 188, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, J.; Xing, G.; Li, S.; Huang, X.; Huang, W. Metal halide perovskites: Stability and sensing-ability. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 10121–10137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, J.; Urban, A.S.; Imran, M.; De Trizio, L.; Manna, L. Metal Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals: Synthesis, Post-Synthesis Modifications, and Their Optical Properties. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 3296–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.C.; Cheacharoen, R.; Leijtens, T.; McGehee, M.D. Understanding Degradation Mechanisms and Improving Stability of Perovskite Photovoltaics. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 3418–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; De Marco, N.; Yang, Y.; Song, T.-B.; Chen, C.-C.; Zhao, H.; Hong, Z.; Zhou, H.; Yang, Y. Under the spotlight: The organic–inorganic hybrid halide perovskite for optoelectronic applications. Nano Today 2015, 10, 355–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moradi, Z.; Fallah, H.; Hajimahmoodzadeh, M. Nanocomposite perovskite based optical sensor with broadband absorption spectrum. Sens. Actuators A 2018, 280, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.-Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, I.-S.; Kim, E.-S.; Wang, Z.-J.; Kim, N.-Y.; Kim, S.-W.; Oh, J.-M. Perovskite-Induced Ultrasensitive and Highly Stable Humidity Sensor Systems Prepared by Aerosol Deposition at Room Temperature. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1907449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Fan, W.; Hills-Kimball, K.; Chen, O.; Wang, L.-Q. Introducing Manganese-Doped Lead Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots: A Simple Synthesis Illustrating Optoelectronic Properties of Semiconductors. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 2300–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Li, F.; Lai, Z.; Cai, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wolfbeis, O.S.; Chen, X. MnII-Doped Cesium Lead Chloride Perovskite Nanocrystals: Demonstration of Oxygen Sensing Capability Based on Luminescent Dopants and Host-Dopant Energy Transfer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 23335–23343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athayde, D.D.; Souza, D.F.; Silva, A.M.A.; Vasconcelos, D.; Nunes, E.H.M.; Diniz da Costa, J.C.; Vasconcelos, W.L. Review of perovskite ceramic synthesis and membrane preparation methods. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 6555–6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ananthakumar, S.; Kumar, J.R.; Babu, S.M. Cesium lead halide (CsPbX3, X=Cl, Br, I) perovskite quantum dots-synthesis, properties, and applications: A review of their present status. J. Photonics Energy 2016, 6, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Protesescu, L.; Yakunin, S.; Nazarenko, O.; Dirin, D.N.; Kovalenko, M.V. Low-Cost Synthesis of Highly Luminescent Colloidal Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals by Wet Ball Milling. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 1300–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chandra Dhal, G.; Dey, S.; Mohan, D.; Prasad, R. Solution Combustion Synthesis of Perovskite-type Catalysts for Diesel Engine Exhaust Gas Purification. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 10489–10493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecija, A.; Vidal, K.; Larrañaga, A.; Luis Ortega-San-Martín, L.; Arriortua, M.I. Synthetic Methods for Perovskite Materials—Structure and Morphology. In Advances in Crystallization Processes; Mastai, Y., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 485–506. [Google Scholar]

- Cernea, M.; Vasiliu, F.; Plapcianu, C.; Bartha, C.; Mercioniu, I.; Pasuk, I.; Lowndes, R.; Trusca, R.; Aldica, G.V.; Pintilie, L. Preparation by sol–gel and solid state reaction methods and properties investigation of double perovskite Sr2FeMoO6. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 33, 2483–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Filho, J.M.C.; Ermakov, V.A.; Marques, F.C. Perovskite Thin Film Synthesised from Sputtered Lead Sulphide. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, M.A.; Fierro, J.L.G. Chemical Structures and Performance of Perovskite Oxides. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 1981–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trots, D.M.; Myagkota, S.V. High-temperature structural evolution of caesium and rubidium triiodoplumbates. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2008, 69, 2520–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plesko, S.; Kind, R.; Roos, J. Structural Phase Transitions in CsPbCl3 and RbCdCl3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1978, 45, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodová, M.; Brožek, J.; Knížek, K.; Nitsch, K. Phase transitions in ternary caesium lead bromide. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2003, 71, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hu, X.; Lu, W.; Chang, S.; Shi, L.; Li, L.; Zhong, H.; Han, J.-B. Elucidating the phase transitions and temperature-dependent photoluminescence of MAPbBr3 single crystal. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 045105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoumpos, C.C.; Malliakas, C.D.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Semiconducting Tin and Lead Iodide Perovskites with Organic Cations: Phase Transitions, High Mobilities, and Near-Infrared Photoluminescent Properties. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 9019–9038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baikie, T.; Fang, Y.; Kadro, J.M.; Schreyer, M.; Wei, F.; Mhaisalkar, S.G.; Graetzel, M.; White, T.J. Synthesis and crystal chemistry of the hybrid perovskite (CH3NH3)PbI3 for solid-state sensitised solar cell applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 5628–5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.-P.; Li, L.-C.; Shellaiah, M.; Sun, K.W. Structural, Photophysical, and Electronic Properties of CH3NH3PbCl3 Single Crystals. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, K.-H.; Li, L.-C.; Shellaiah, M.; Wen Sun, K. Structural and Photophysical Properties of Methylammonium Lead Tribromide (MAPbBr3) Single Crystals. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stoerzinger, K.A.; Hong, W.T.; Azimi, G.; Giordano, L.; Lee, Y.-L.; Crumlin, E.J.; Biegalski, M.D.; Bluhm, H.; Varanasi, K.K.; Shao-Horn, Y. Reactivity of Perovskites with Water: Role of Hydroxylation in Wetting and Implications for Oxygen Electrocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 18504–18512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frost, J.M.; Butler, K.T.; Brivio, F.; Hendon, C.H.; van Schilfgaarde, M.; Walsh, A. Atomistic Origins of High-Performance in Hybrid Halide Perovskite Solar Cells. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 2584–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bass, K.K.; McAnally, R.E.; Zhou, S.; Djurovich, P.I.; Thompson, M.E.; Melot, B.C. Influence of moisture on the preparation, crystal structure, and photophysical properties of organohalide perovskites. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 15819–15822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralaiarisoa, M.; Rodríguez, Y.; Salzmann, I.; Vaillant, L.; Koch, N. Impact of solvent exposure on the structure and electronic properties of CH3NH3PbI3−xClx mixed halide perovskite films. Appl. Phys. A 2019, 125, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlefeld, J.F.; Borland, W.J.; Maria, J.-P. Enhanced Dielectric and Crystalline Properties in Ferroelectric Barium Titanate Thin Films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 1199–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Bi, L.; Zhang, J.; Cao, H.; Zhao, X.S. The role of oxygen vacancies of ABO3 perovskite oxides in the oxygen reduction reaction. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 1408–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karppinen, M.; Matvejeff, M.; Salomäki, K.; Yamauchi, H. Oxygen content analysis of functional perovskite-derived cobalt oxides. J. Mater. Chem. 2002, 12, 1761–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, K. Glory of piezoelectric perovskites. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2015, 16, 046001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaldin, N.A.; Cheong, S.-W.; Ramesh, R. Multiferroics: Past, present, and future. Phys. Today 2010, 63, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arandiyan, H.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Rezaei, M.; Dai, H. Ordered meso- and macroporous perovskite oxide catalysts for emerging applications. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 6484–6502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, L.; Ghimire, S.; Subrahmanyam, C.; Miyasaka, T.; Biju, V. Synthesis, optoelectronic properties and applications of halide perovskites. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 2869–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manser, J.S.; Christians, J.A.; Kamat, P.V. Intriguing Optoelectronic Properties of Metal Halide Perovskites. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 12956–13008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldakov, D.; Reiss, P. Safer-by-Design Fluorescent Nanocrystals: Metal Halide Perovskites vs. Semiconductor Quantum Dots. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 12527–12541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shahrokhi, S.; Gao, W.; Wang, Y.; Anandan, P.R.; Rahaman, M.Z.; Singh, S.; Wang, D.; Cazorla, C.; Yuan, G.; Liu, J.-M.; et al. Emergence of Ferroelectricity in Halide Perovskites. In Small Methods; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; p. 2000149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, F.; Markov, S.; Wang, R.; Kwok, Y.; Zhou, W.; Liu, L.; Zheng, X.; Chen, G.; Yam, C. Enhanced Photovoltaic Properties Induced by Ferroelectric Domain Structures in Organometallic Halide Perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 11151–11158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Sun, K.; Wang, J. Perovskites for photovoltaics: A combined review of organic–inorganic halide perovskites and ferroelectric oxide perovskites. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 18809–18828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Han, K. Charge-Carrier Dynamics of Lead-Free Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 3188–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unni, K.; Manjot, K.; Manjeet, K.; Akshay, K. Factors affecting the stability of perovskite solar cells: A comprehensive review. J. Photonics Energy 2019, 9, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, D.; Aziz, A.; Dawson, J.A.; Walker, A.B.; Islam, M.S. Putting the Squeeze on Lead Iodide Perovskites: Pressure-Induced Effects To Tune Their Structural and Optoelectronic Behavior. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 4063–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shimada, K.; Takashima, H.; Wang, R.; Prijamboedi, B.; Miura, N.; Itoh, M. Capacitance Temperature Sensor Using Ferroelectric (Sr0.95Ca0.05)TiO3 Perovskite. Ferroelectrics 2006, 331, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.; Zhou, Y.-H.; Song, J.-L.; Zhang, C. An ABX3 organic–inorganic perovskite-type material with the formula (C5N2H9)CdCl3: Application for detection of volatile organic solvent molecules. Polyhedron 2017, 131, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jancik Prochazkova, A.; Demchyshyn, S.; Yumusak, C.; Másilko, J.; Brüggemann, O.; Weiter, M.; Kaltenbrunner, M.; Sariciftci, N.S.; Krajcovic, J.; Salinas, Y.; et al. Proteinogenic Amino Acid Assisted Preparation of Highly Luminescent Hybrid Perovskite Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 4267–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, B.; Shivkumar, A.; Charles, B.; Evans, R.C. Synthetic factors affecting the stability of methylammonium lead halide perovskite nanocrystals. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 11694–11702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, F.; Huang, Y.; Lin, F.; Chen, X. Wavelength-Shift-Based Colorimetric Sensing for Peroxide Number of Edible Oil Using CsPbBr3 Perovskite Nanocrystals. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 14183–14187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hahn, Y.-B.; Ahmad, R.; Tripathy, N. Chemical and biological sensors based on metal oxide nanostructures. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 10369–10385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahesh Kumar, M.; Post, M.L. Effect of grain boundaries on hydrocarbon sensing in Fe-doped p-type semiconducting perovskite SrTiO3 films. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 97, 114916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qin, J.; Cui, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhu, S.; Li, Z.; Liang, Y. Synthesis of three-dimensionally ordered macroporous LaFeO3 with enhanced methanol gas sensing properties. Sens. Actuators B 2015, 209, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemons, M.; Leifert, A.; Simon, U. Preparation and Gas Sensing Characteristics of Nanoparticulate p-Type Semiconducting LnFeO3 and LnCrO3 Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 2189–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalairajan, S.; Girija, K.; Mastelaro, V.R.; Ponpandian, N. Surface Morphology-Dependent Room-Temperature LaFeO3 Nanostructure Thin Films as Selective NO2 Gas Sensor Prepared by Radio Frequency Magnetron Sputtering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 13917–13927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

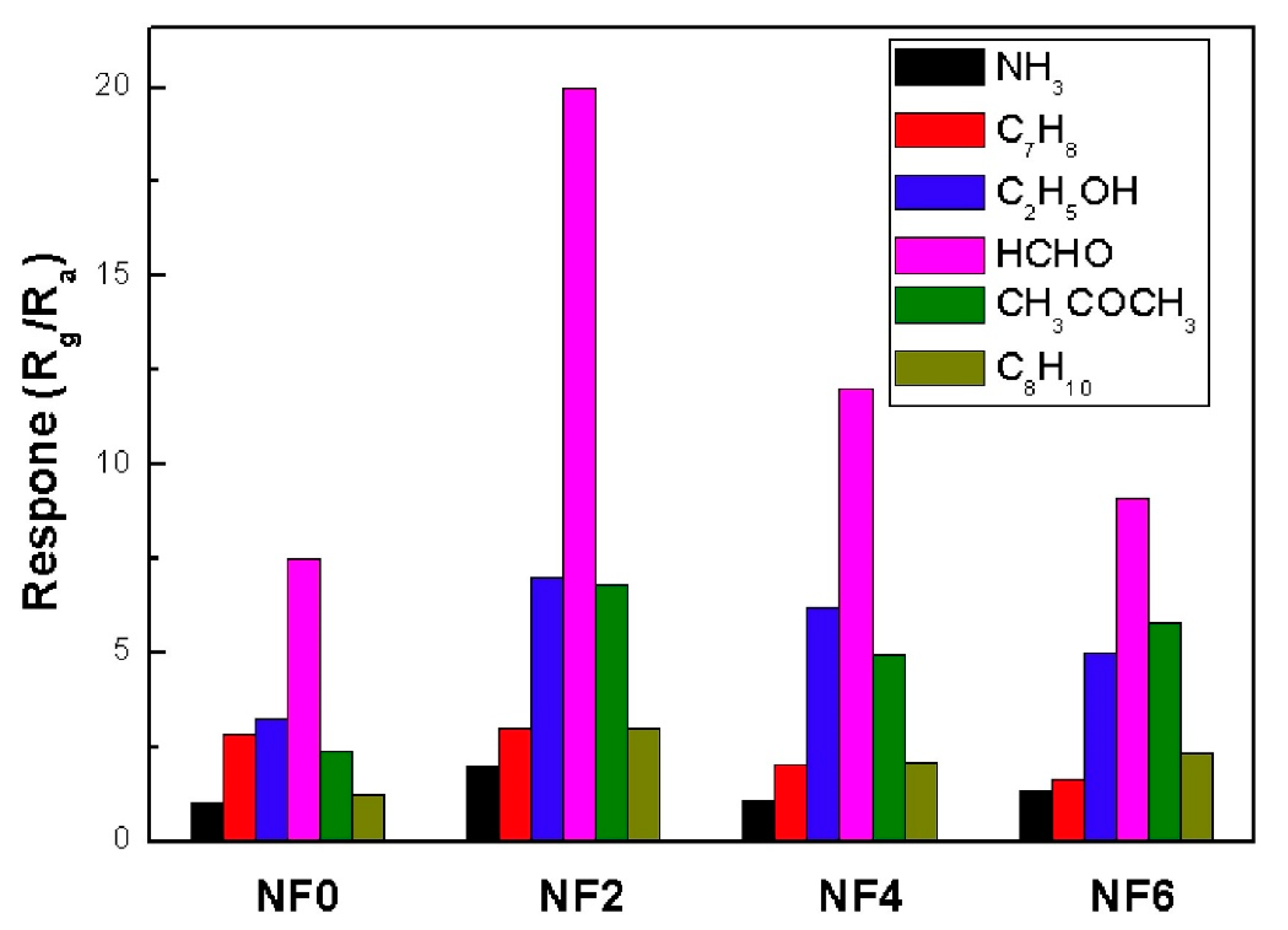

- Wang, Y.-Z.; Zhong, H.; Li, X.-M.; Jia, F.-F.; Shi, Y.-X.; Zhang, W.-G.; Cheng, Z.-P.; Zhang, L.-L.; Wang, J.-K. Perovskite LaTiO3–Ag0.2 nanomaterials for nonenzymatic glucose sensor with high performance. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 48, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giang, H.T.; Duy, H.T.; Ngan, P.Q.; Thai, G.H.; Thu, D.T.A.; Thu, D.T.; Toan, N.N. Hydrocarbon gas sensing of nano-crystalline perovskite oxides LnFeO3 (Ln=La, Nd and Sm). Sens. Actuators B 2011, 158, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itagaki, Y.; Fujihashi, K.; Aono, H.; Mori, M.; Sadaoka, Y. VOC sensing behavior of semiconducting Sm2O3/SmFeO3 mixtures. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2015, 123, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tasaki, T.; Takase, S.; Shimizu, Y. Impedancemetric acetylene gas sensing properties of Sm–Fe-based perovskite-type oxide-based thick-film device. Sens. Actuators B 2013, 187, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; Itagaki, Y.; Sadaoka, Y. Effect of VOC on ozone detection using semiconducting sensor with SmFe1−xCoxO3 perovskite-type oxides. Sens. Actuators B 2012, 163, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giang, H.T.; Duy, H.T.; Ngan, P.Q.; Thai, G.H.; Thu, D.T.A.; Thu, D.T.; Toan, N.N. High sensitivity and selectivity of mixed potential sensor based on Pt/YSZ/SmFeO3 to NO2 gas. Sens. Actuators B 2013, 183, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroftei, C.; Popa, P.D.; Iacomi, F.; Leontie, L. The influence of Zn2+ ions on the microstructure, electrical and gas sensing properties of La0.8Pb0.2FeO3 perovskite. Sens. Actuators B 2014, 191, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, G.; Wang, G.; Irvine, J.T.S. Synthesis and applications of nanoporous perovskite metal oxides. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 3623–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

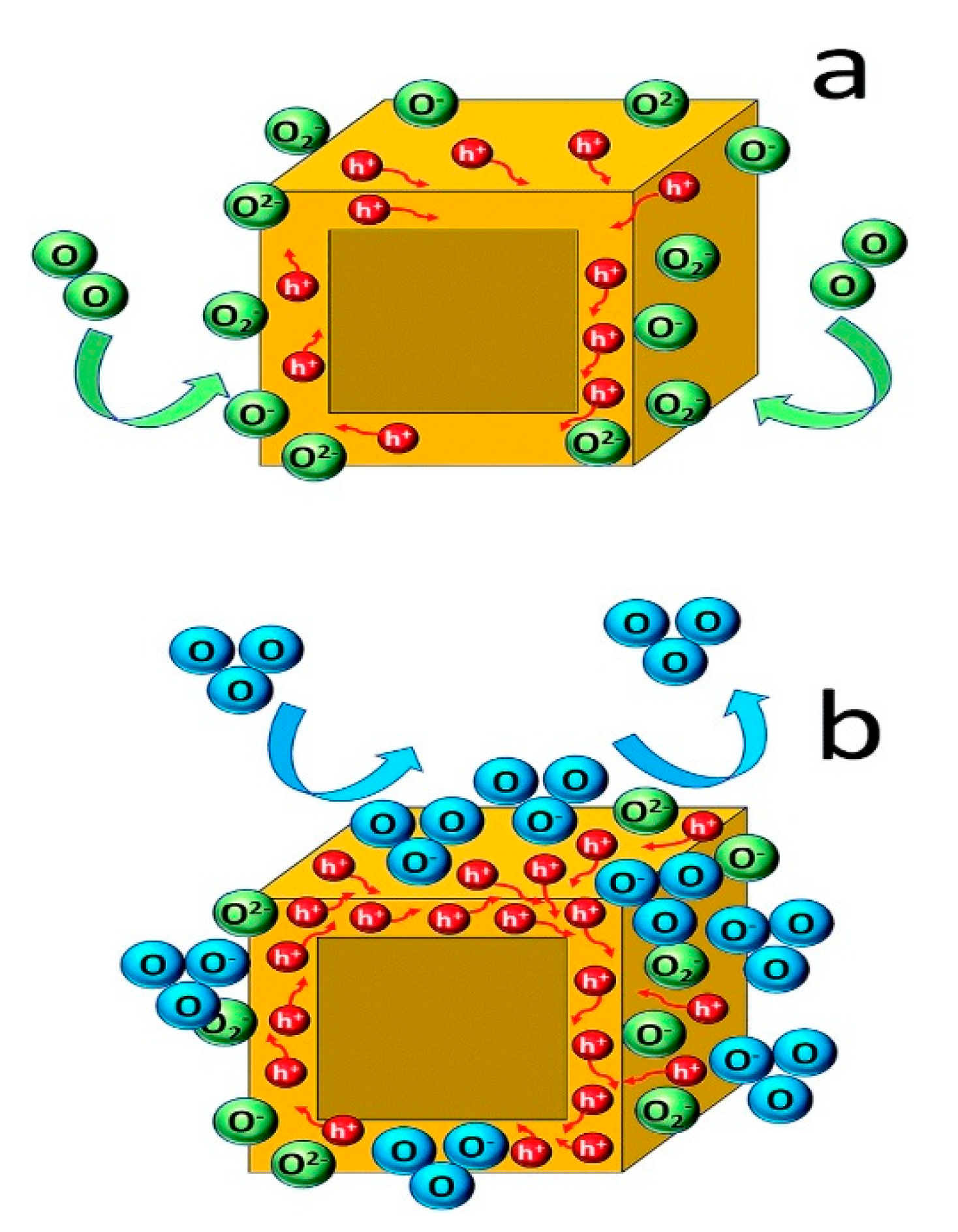

- Bulemo, P.M.; Kim, I.-D. Recent advances in ABO3 perovskites: Their gas-sensing performance as resistive-type gas sensors. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 2020, 57, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Enhessari, M.; Salehabadi, A. Perovskites-Based Nanomaterials for Chemical Sensors. In Progresses in Chemical Sensor; Wang, W., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2016; pp. 59–91. [Google Scholar]

- Degler, D. Trends and Advances in the Characterization of Gas Sensing Materials Based on Semiconducting Oxides. Sensors 2018, 18, 3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, B.; Gao, P.-X. Metal Oxide Nanoarrays for Chemical Sensing: A Review of Fabrication Methods, Sensing Modes, and Their Inter-correlations. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cao, E.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Hao, W.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y. Enhanced ethanol sensing performance for chlorine doped nanocrystalline LaFeO3-δ powders by citric sol-gel method. Sens. Actuators B 2017, 251, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yi, J. Enhanced ethanol gas sensing performance of ZnO nanoflowers decorated with LaMnO3 perovskite nanoparticles. Mater. Lett. 2018, 216, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Lv, X.; Hu, Z.; Xu, A.; Feng, C. Semiconductor Metal Oxides as Chemoresistive Sensors for Detecting Volatile Organic Compounds. Sensors 2019, 19, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, X.-H.; Li, H.-Y.; Kweon, S.-H.; Jeong, S.-Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Nahm, S. Highly Sensitive and Selective PbTiO3 Gas Sensors with Negligible Humidity Interference in Ambient Atmosphere. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 5240–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, E.; Wu, A.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, W.; Sun, L. Enhanced Ethanol Sensing Performance of Au and Cl Comodified LaFeO3 Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 1541–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Ma, S.Y.; Shen, X.F.; Wang, T.T.; Jiang, X.H.; Chen, Q.; Qiang, Z.; Yang, H.M.; Chen, H. PrFeO3 hollow nanofibers as a highly efficient gas sensor for acetone detection. Sens. Actuators B 2018, 255, 2546–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

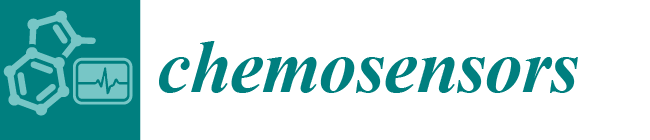

- Yin, Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, N.; Ruan, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y. Improved gas sensing properties of silver-functionalized ZnSnO3 hollow nanocubes. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2018, 5, 2123–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qin, H.; Zhang, P.; Hu, J. High Sensing Properties of 3 wt % Pd-Doped SmFe1–xMgxO3 Nanocrystalline Powders to Acetone Vapor with Ultralow Concentrations under Light Illumination. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 15558–15564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, K.; Xie, R.; Huang, H.; Peng, T.; Jia, R.; Huo, J. A novel and highly responsive acetone sensor based on La1−xYxMnO3+δ nanoparticles. Mater. Lett. 2019, 257, 126725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

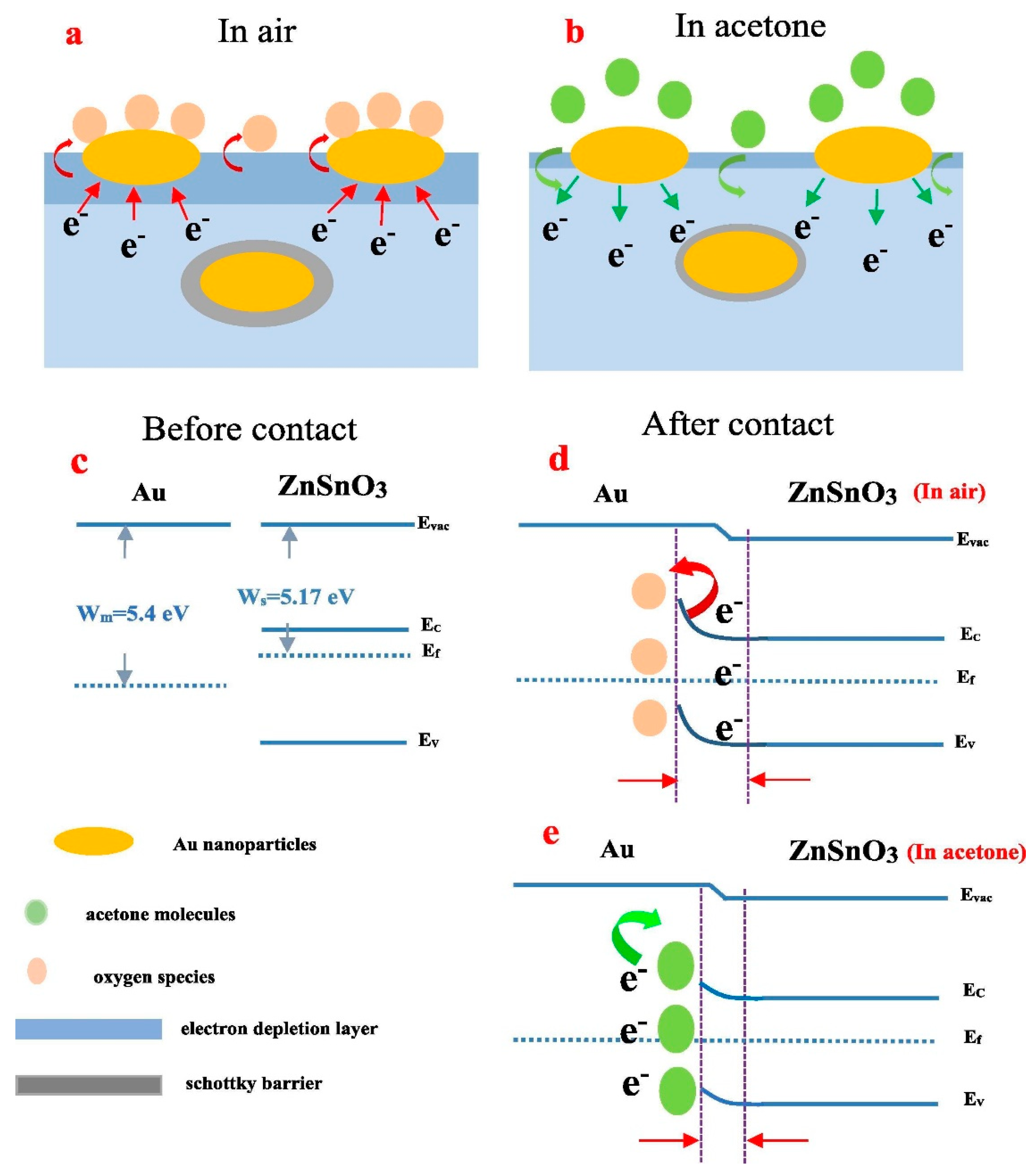

- Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Ma, S.; Wang, P.; Zhang, G.; Chen, W.; Jiao, H.; Liu, L.; Xu, X. Enhanced acetone sensor based on Au functionalized In-doped ZnSnO3 nanofibers synthesized by electrospinning method. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 543, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, K.; Lv, T.; Shen, K.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Q. Facile lotus-leaf-templated synthesis and enhanced xylene gas sensing properties of Ag-LaFeO3 nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 6138–6145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Ma, S.Y.; Xu, X.L.; Xu, X.H.; Pei, S.T.; Tie, Y.; Cao, P.F.; Liu, W.W.; Wang, B.J.; Zhang, R.; et al. Rough SmFeO3 nanofibers as an optimization ethylene glycol gas sensor prepared by electrospinning. Mater. Lett. 2020, 268, 127575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, P.; Lu, R.; Li, A.; Zhao, S.; Liu, W.; Wei, D.; Wei, K. Fabrication, characterization and n-propanol sensing properties of perovskite-type ZnSnO3 nanospheres based gas sensor. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 509, 145335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Guo, S.; Chen, C.; Sun, L.; Chen, Y.; Guo, W.; Ruan, S. High sensitive and fast formaldehyde gas sensor based on Ag-doped LaFeO3 nanofibers. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 695, 1122–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Ma, J.; Qiao, X.; Cui, Y.; Jia, L.; Wang, H. Hierarchical porous LaFeO3 nanostructure for efficient trace detection of formaldehyde. Sens. Actuators B 2020, 313, 128022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, A.; Majumder, S.B.; Dewan, M.; Roy Chaudhuri, A. Hydrogen sensing characteristics of perovskite based calcium doped BiFeO3 thin films. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 18648–18656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gildo-Ortiz, L.; Reyes-Gómez, J.; Flores-Álvarez, J.M.; Guillén-Bonilla, H.; Olvera, M.d.l.L.; Rodríguez Betancourtt, V.M.; Verde-Gómez, Y.; Guillén-Cervantes, A.; Santoyo-Salazar, J. Synthesis, characterization and sensitivity tests of perovskite-type LaFeO3 nanoparticles in CO and propane atmospheres. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 18821–18827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.-C.; Li, H.-Y.; Cao, T.-C.; Cai, Z.-X.; Wang, X.-X.; Guo, X. Characteristics and sensing properties of CO gas sensors based on LaCo1−xFexO3 nanoparticles. Solid State Ion. 2017, 303, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, C.R.; Martínez-Preciado, A.H.; López-Mena, E.R.; Elías-Zuñiga, A.; Cayetano-Castro, N.; Ceballos-Sanchez, O. Improvement of the gas sensing response of nanostructured LaCoO3 by the addition of Ag nanoparticles. Sens. Actuators B 2017, 246, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gildo-Ortiz, L.; Guillén-Bonilla, H.; Rodríguez-Betancourtt, V.M.; Blanco-Alonso, O.; Guillén-Bonilla, A.; Santoyo-Salazar, J.; Romero-Ibarra, I.C.; Reyes-Gómez, J. Key processing of porous and fibrous LaCoO3 nanostructures for successful CO and propane sensing. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 15402–15410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gildo-Ortiz, L.; Rodríguez-Betancourtt, V.M.; Blanco-Alonso, O.; Guillén-Bonilla, A.; Guillén-Bonilla, J.T.; Guillén-Cervantes, A.; Santoyo-Salazar, J.; Guillén-Bonilla, H. A simple route for the preparation of nanostructured GdCoO3 via the solution method, as well as its characterization and its response to certain gases. Results Phys. 2019, 12, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, S.B.; Hona, R.K.; Ramezanipour, F. Effect of Structure on Sensor Properties of Oxygen-Deficient Perovskites, A2BB′O5 (A = Ca, Sr; B = Fe; B′ = Fe, Mn) for Oxygen, Carbon Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide Sensing. J. Electron. Mater. 2020, 49, 1557–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Ma, L.; Meng, W.; Li, Y.; He, Z.; Wang, L. Impedancemetric NO2 sensor based on Pd doped perovskite oxide sensing electrode conjunction with phase angle response. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 265, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palimar, S.; Kaushik, S.D.; Siruguri, V.; Swain, D.; Viegas, A.E.; Narayana, C.; Sundaram, N.G. Investigation of Ca substitution on the gas sensing potential of LaFeO3 nanoparticles towards low concentration SO2 gas. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 13547–13555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Hao, X.; Yang, X.; Liang, X.; Liu, F.; Liu, T.; Yang, C.; Zhu, H.; Lu, G. Sub-ppb SO2 gas sensor based on NASICON and LaxSm1−xFeO3 sensing electrode. Sens. Actuators B 2018, 256, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queraltó, A.; Graf, D.; Frohnhoven, R.; Fischer, T.; Vanrompay, H.; Bals, S.; Bartasyte, A.; Mathur, S. LaFeO3 Nanofibers for High Detection of Sulfur-Containing Gases. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 6023–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresita, V.M.; Manikandan, A.; Josephine, B.A.; Sujatha, S.; Antony, S.A. Electromagnetic Properties and Humidity-Sensing Studies of Magnetically Recoverable LaMgxFe1−xO3−δ Perovskites Nano-photocatalysts by Sol-Gel Route. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2016, 29, 1691–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Xu, M.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, H. Super-fast response humidity sensor based on La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 nanocrystals prepared by PVP-assisted sol-gel method. Sens. Actuators B 2018, 258, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ads, E.H.; Galal, A.; Atta, N.F. The effect of A-site doping in a strontium palladium perovskite and its applications for non-enzymatic glucose sensing. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 16183–16196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Sunarso, J.; Miao, J.; Sun, H.; Dai, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, W.; Shao, Z. A highly sensitive perovskite oxide sensor for detection of p-phenylenediamine in hair dyes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 369, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atta, N.F.; Galal, A.; El-Ads, E.H. Effect of B-site doping on Sr2PdO3 perovskite catalyst activity for non-enzymatic determination of glucose in biological fluids. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 852, 113523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa Silva, E.; Nicolini, J.V.; Yamauchi, L.; Machado, T.M.; Curi, M.; Furtado, J.G.; Secchi, A.R.; Ferraz, H.C. Carbon-based electrode loaded with Y-doped SrTiO3 perovskite as support for enzyme immobilization in biosensors. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 3592–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayhomayun, Z.; Ghani, K.; Zargoosh, K. Surfactant-assisted synthesis of fluorescent SmCrO3 nanopowder and its application for fast detection of nitroaromatic and nitramine explosives in solution. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 247, 122899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Rodríguez, M.A.; Lozano-Gorrín, A.D.; Martín, I.R.; Rodríguez-Mendoza, U.R.; Lavín, V. Comparison of the sensitivity as optical temperature sensor of nano-perovskite doped with Nd3+ ions in the first and second biological windows. Sens. Actuators B 2018, 255, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, C.R.; López-Alvarez, M.A.; Martínez-Preciado, A.H.; Oleinikov, V. Ultraviolet Detection and Photocatalytic Activity of Nanostructured LaCoO3 Prepared by Solution-Polymerization. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, Q9–Q14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Chen, D.; Yao, X.; Zhang, K.; Qu, F.; Qin, L.; Huang, Y.; Li, J. Recent Progress and Development in Inorganic Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots for Photoelectrochemical Applications. Small 2020, 16, 1903398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, Z.; Luo, M.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, C.; Xu, J.; Huang, B.; Luo, F.; et al. Rare-earth-containing perovskite nanomaterials: Design, synthesis, properties and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 1109–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aamir, M.; Sher, M.; Malik, M.A.; Revaprasadu, N.; Akhtar, J. A facile approach for selective and sensitive detection of aqueous contamination in DMF by using perovskite material. Mater. Lett. 2016, 183, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Liao, J.-F.; Huang, Z.-G.; Wei, J.-H.; Wang, X.-D.; Li, W.-G.; Chen, H.-Y.; Kuang, D.-B.; Su, C.-Y. A Highly Red-Emissive Lead-Free Indium-Based Perovskite Single Crystal for Sensitive Water Detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5277–5281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Dai, Z.; Bao, J.; Xu, X. Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots as a Photoluminescence Probe for Metal Ions. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1700150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

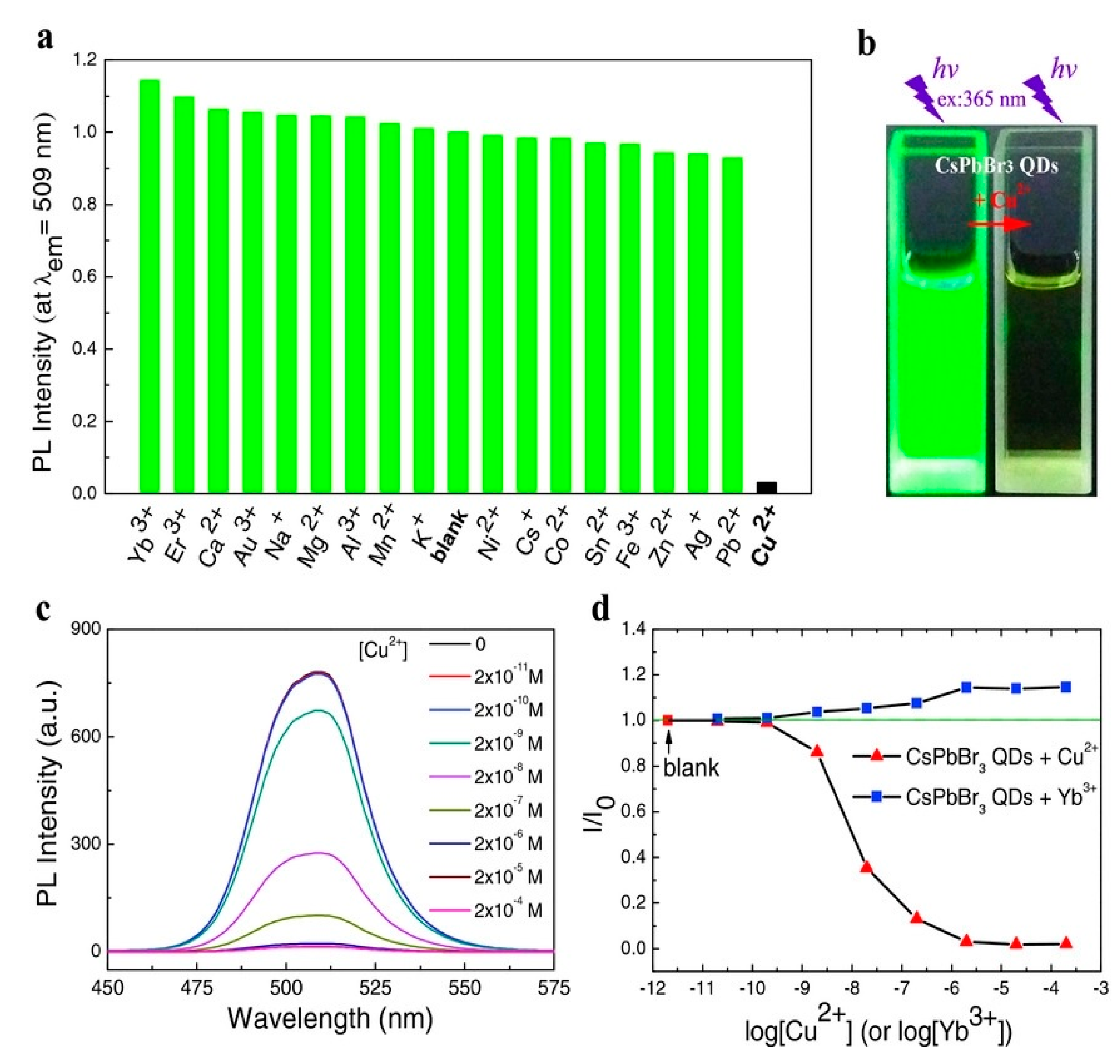

- Liu, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhu, T.; Deng, M.; Ikechukwu, I.P.; Huang, W.; Yin, G.; Bai, Y.; Qu, D.; Huang, X.; et al. All-inorganic CsPbBr3 perovskite quantum dots as a photoluminescent probe for ultrasensitive Cu2+ detection. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 4793–4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Zhou, D.; Pan, G.; Xu, W.; Chen, X.; Li, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, J.; Ji, Y.; Song, H. Europium-Doped Lead-Free Cs3Bi2Br9 Perovskite Quantum Dots and Ultrasensitive Cu2+ Detection. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 8397–8404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

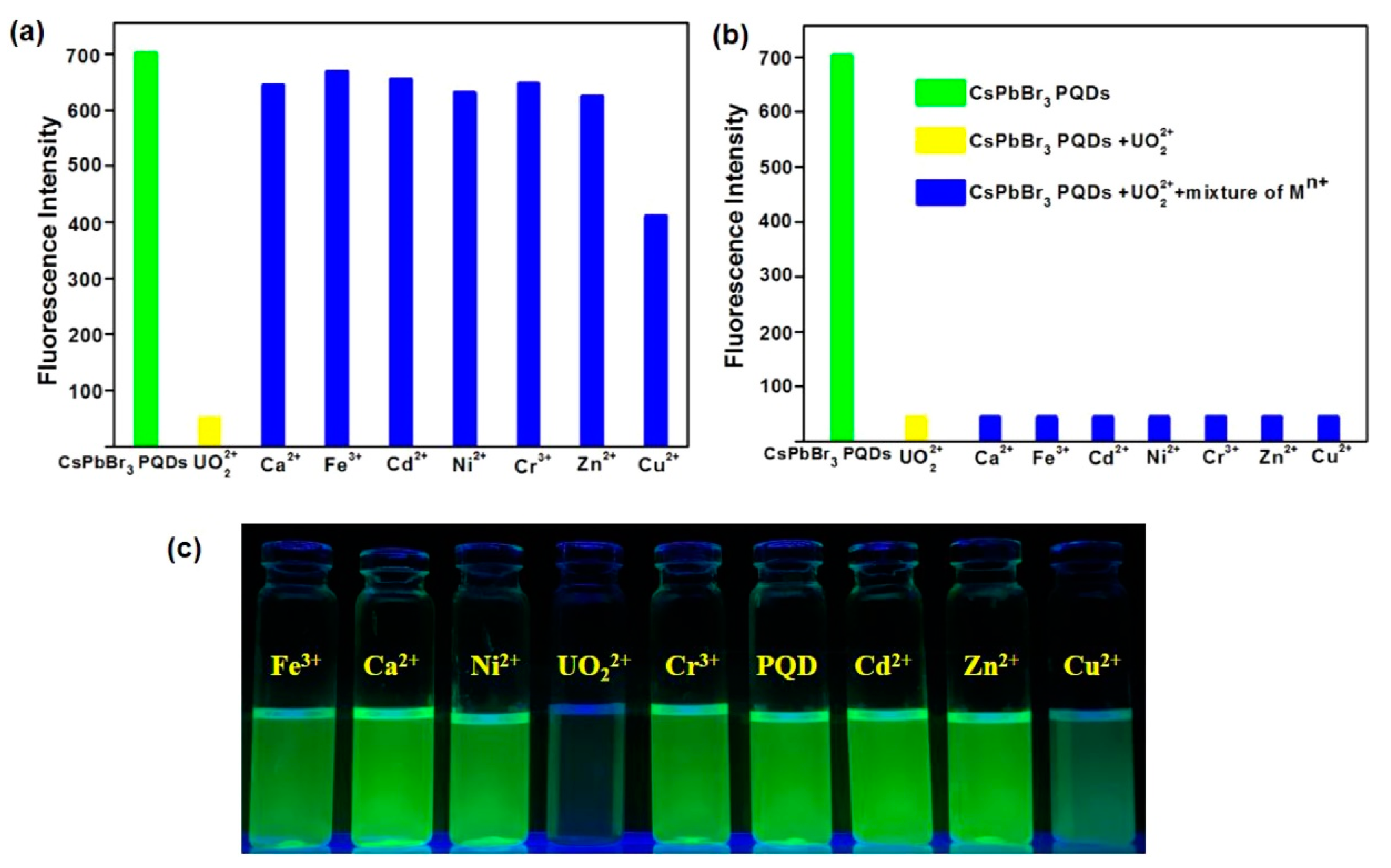

- Halali, V.V.; Shwetha Rani, R.; Geetha Balakrishna, R.; Budagumpi, S. Ultra-trace level chemosensing of uranyl ions; scuffle between electron and energy transfer from perovskite quantum dots to adsorbed uranyl ions. Microchem. J. 2020, 156, 104808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Qin, J.; Umar, A.A.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Cui, X.; Li, X.; Zheng, L.; Zhan, Y. Lead-Free Cs2BiAgBr6 Double Perovskite-Based Humidity Sensor with Superfast Recovery Time. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1902234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Fu, X.; Fusco, Z.; Bo, R.; Xing, B.; Nguyen, H.T.; Barugkin, C.; Zheng, J.; Lau, C.F.J.; et al. Light-activated inorganic CsPbBr2I perovskite for room-temperature self-powered chemical sensing. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 24187–24193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protesescu, L.; Yakunin, S.; Bodnarchuk, M.I.; Krieg, F.; Caputo, R.; Hendon, C.H.; Yang, R.X.; Walsh, A.; Kovalenko, M.V. Nanocrystals of Cesium Lead Halide Perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, and I): Novel Optoelectronic Materials Showing Bright Emission with Wide Color Gamut. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 3692–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Bo, R.; Barugkin, C.; Zheng, J.; Ma, Q.; Huang, S.; Ho-Baillie, A.W.Y.; Catchpole, K.R.; Tricoli, A. Superior Self-Powered Room-Temperature Chemical Sensing with Light-Activated Inorganic Halides Perovskites. Small 2018, 14, 1702571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hu, H.; Xia, Z.; Gao, W.; Gou, W.; Qu, Y.; Ma, Y. CsPbBr3 perovskite nanocrystals as highly selective and sensitive spectrochemical probes for gaseous HCl detection. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cai, Q.; Luo, F.; Dong, N.; Guo, L.; Qiu, B.; Lin, Z. Sensitive Fluorescent Sensor for Hydrogen Sulfide in Rat Brain Microdialysis via CsPbBr3 Quantum Dots. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 15915–15921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

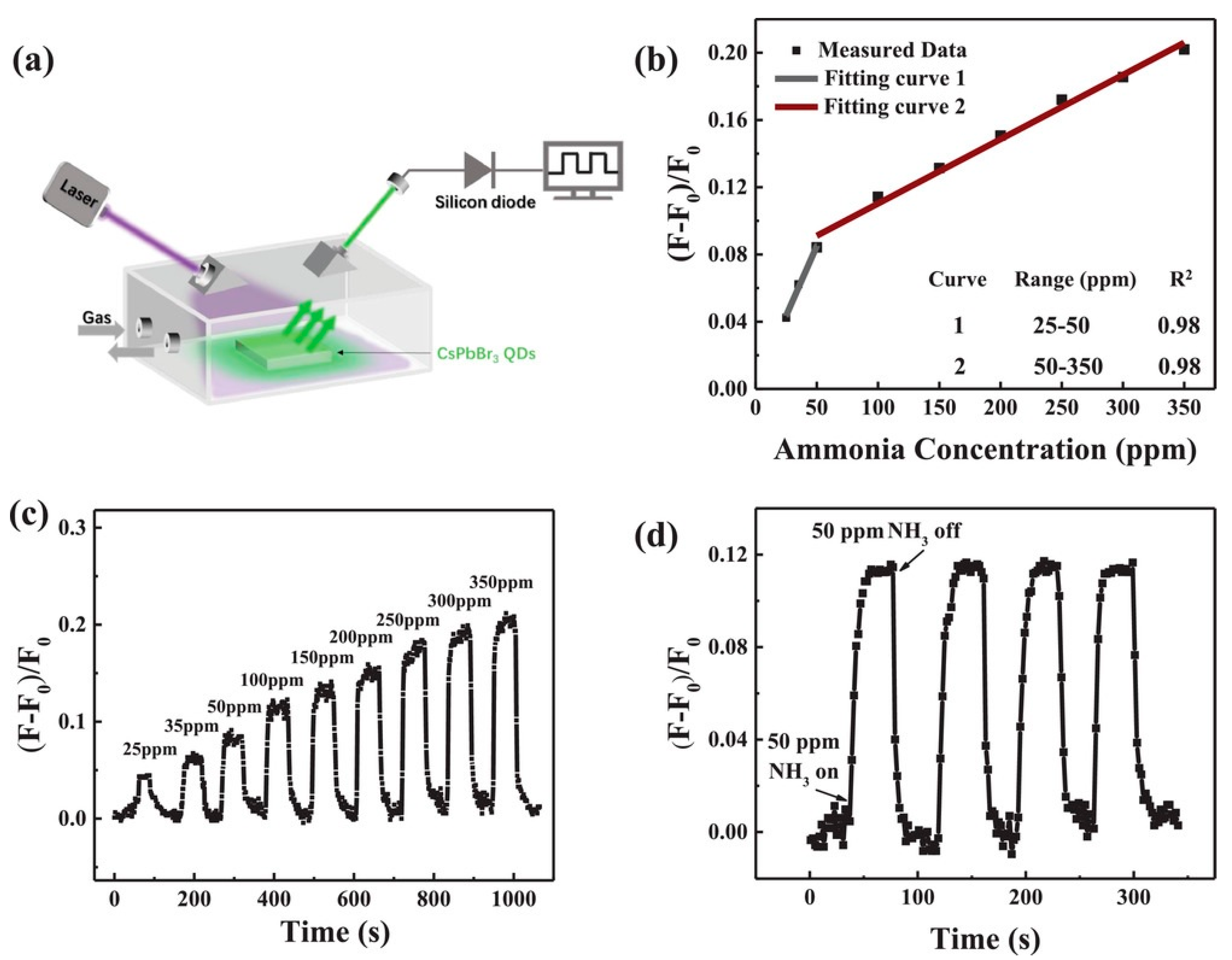

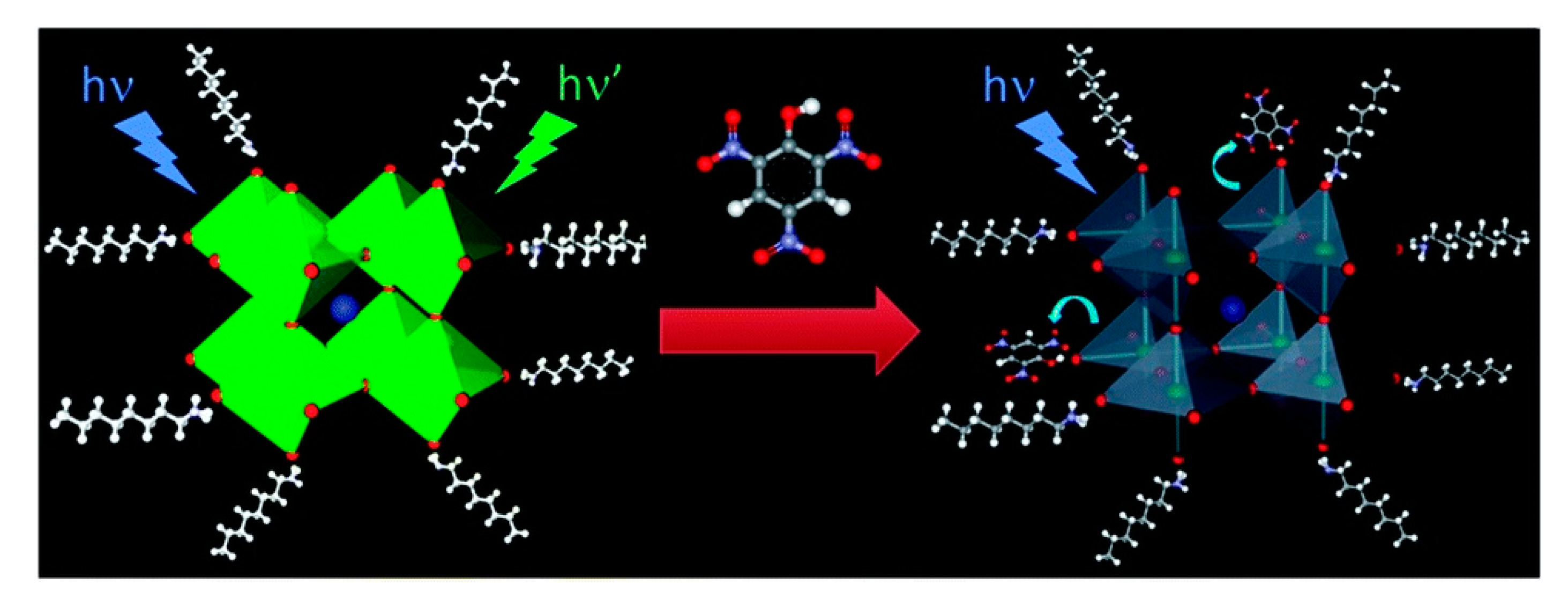

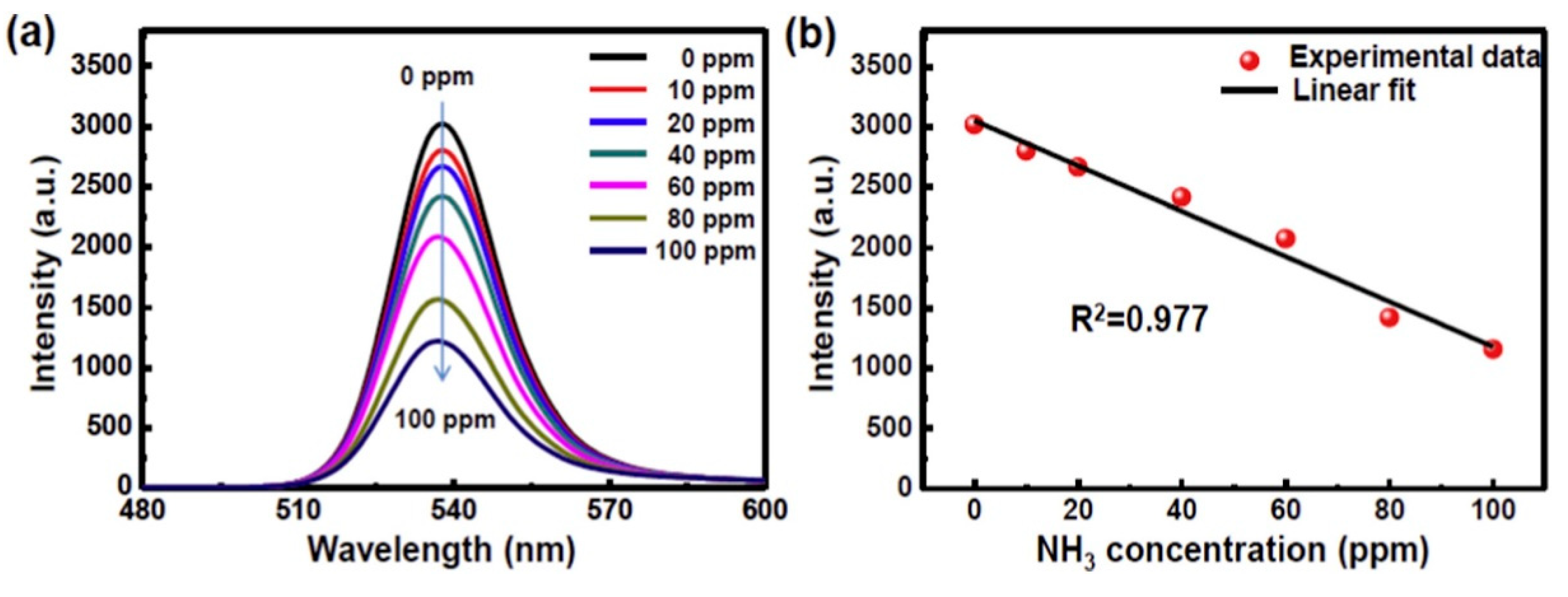

- Huang, H.; Hao, M.; Song, Y.; Dang, S.; Liu, X.; Dong, Q. Dynamic Passivation in Perovskite Quantum Dots for Specific Ammonia Detection at Room Temperature. Small 2020, 16, 1904462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brintakis, K.; Gagaoudakis, E.; Kostopoulou, A.; Faka, V.; Argyrou, A.; Binas, V.; Kiriakidis, G.; Stratakis, E. Ligand-free all-inorganic metal halide nanocubes for fast, ultra-sensitive and self-powered ozone sensors. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 2699–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

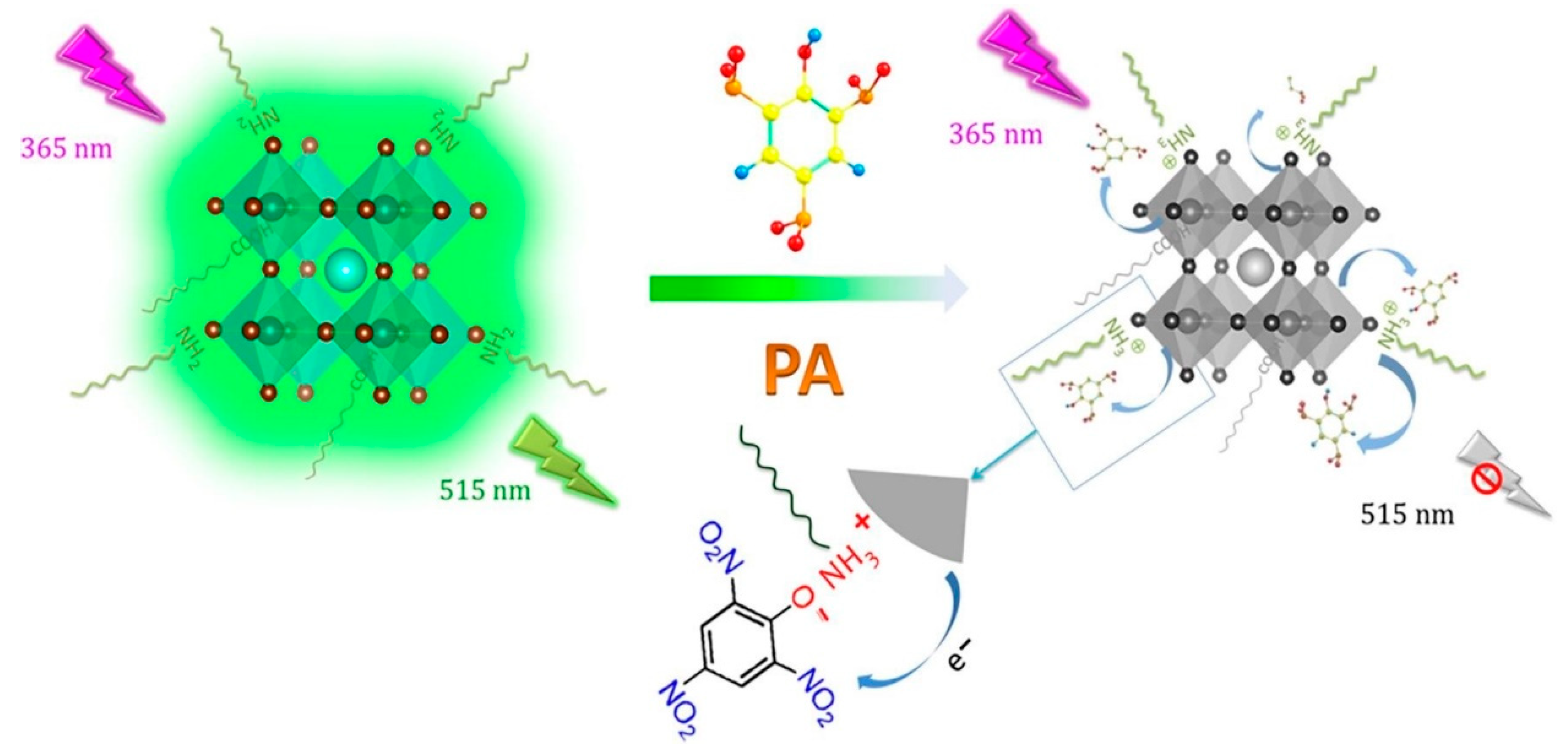

- Chen, X.; Sun, C.; Liu, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhang, K.; Asiri, A.M.; Marwani, H.M.; Tan, H.; Ai, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. All-inorganic perovskite quantum dots CsPbX3 (Br/I) for highly sensitive and selective detection of explosive picric acid. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 379, 122360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Bai, Z.; Dong, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, R.; Zou, B.; Li, J.; Zhong, H. Aggregation-Induced Emission Features of Organometal Halide Perovskites and Their Fluorescence Probe Applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2015, 3, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthu, C.; Nagamma, S.R.; Nair, V.C. Luminescent hybrid perovskite nanoparticles as a new platform for selective detection of 2,4,6-trinitrophenol. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 55908–55911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, F.; Cai, Z.; Wang, Y.; Luo, F.; Chen, X. An ultrasensitive and reversible fluorescence sensor of humidity using perovskite CH3NH3PbBr3. J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 9651–9655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Huang, L.; Yue, S.; Lu, S.; Liu, K.; Azam, M.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Qu, S.; Wang, Z. Turning a disadvantage into an advantage: Synthesizing high-quality organometallic halide perovskite nanosheet arrays for humidity sensors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 2504–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Leng, M.; Hu, Z.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Liu, H.; Gao, L.; Niu, G.; Tang, J. Reversible luminescent humidity chromism of organic–inorganic hybrid PEA2MnBr4 single crystals. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 5662–5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.-Q.; Tan, T.; Tian, X.-K.; Li, Y.; Deng, P. Visual and sensitive fluorescent sensing for ultratrace mercury ions by perovskite quantum dots. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 986, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Lo, M.-F.; Lee, C.-S. Stabilization of organometallic halide perovskite nanocrystals in aqueous solutions and their applications in copper ion detection. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 5784–5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-H.; Liao, M.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Chueh, C.-C. Recent progress of anion-based 2D perovskites with different halide substitutions. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 4294–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

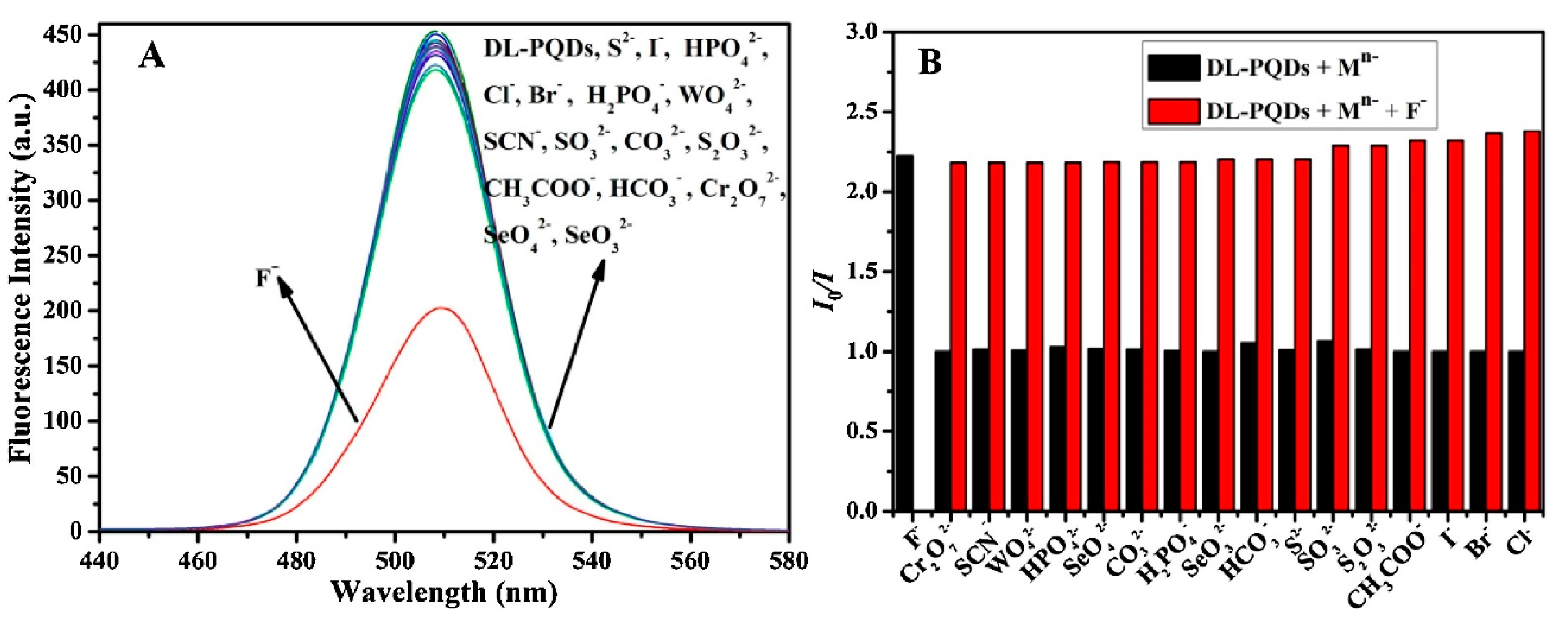

- Lu, L.-Q.; Ma, M.-Y.; Tan, T.; Tian, X.-K.; Zhou, Z.-X.; Yang, C.; Li, Y. Novel dual ligands capped perovskite quantum dots for fluoride detection. Sens. Actuators B 2018, 270, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Kirakosyan, A.; Choi, J.; Kim, J.H. Detection of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), aliphatic amines, using highly fluorescent organic-inorganic hybrid perovskite nanoparticles. Dyes Pigments 2017, 147, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhou, J.; Molokeev, M.S.; Jiang, X.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, J.; Xia, Z. Lead-Free Hybrid Metal Halides with a Green-Emissive [MnBr4] Unit as a Selective Turn-On Fluorescent Sensor for Acetone. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 13464–13470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.-Y.; Zhang, L.-X.; Yin, J.; Chen, J.-J.; Bie, L.-J. Ppt-level benzene detection and gas sensing mechanism using (C4H9NH3)2PbI2Br2 organic–inorganic layered perovskite. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2018, 5, 3046–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur’aini, A.; Oh, I. Volatile organic compound gas sensors based on methylammonium lead iodide perovskite operating at room temperature. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 12982–12987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bao, C.; Yang, J.; Zhu, W.; Zhou, X.; Gao, H.; Li, F.; Fu, G.; Yu, T.; Zou, Z. A resistance change effect in perovskite CH3NH3PbI3 films induced by ammonia. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 15426–15429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maity, A.; Raychaudhuri, A.K.; Ghosh, B. High sensitivity NH3 gas sensor with electrical readout made on paper with perovskite halide as sensor material. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sheikh, A.D.; Vhanalakar, V.; Katware, A.; Pawar, K.; Patil, P.S. Two-Step Antisolvent Precipitated MAPbI3-Pellet-Based Robust Room-Temperature Ammonia Sensor. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2019, 4, 1900251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; He, J.; Zhang, L. Synthesis and high ammonia gas sensitivity of (CH3NH3)PbBr3−xIx perovskite thin film at room temperature. Sens. Actuators B 2020, 309, 127786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, W.; She, C.; Jia, S.; Liu, S.; Yue, F.; Jing, C.; Cheng, Y.; Chu, J. Stable fluorescent NH3 sensor based on MAPbBr3 encapsulated by tetrabutylammonium cations. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 835, 155386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhou, S.; Tong, L.; Liao, Y.; Yi, J.; Qi, Y.; Yao, J. Large scale quantum dynamics investigations on the sensing mechanism of H2O, acetone, NO2 and O3 adsorption on the (MA)2Pb(SCN)2I2 surface. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 21223–21235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Yuan, W.; Qian, L.; Chen, S.; Shi, G. High-performance gas sensors based on a thiocyanate ion-doped organometal halide perovskite. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 12876–12881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

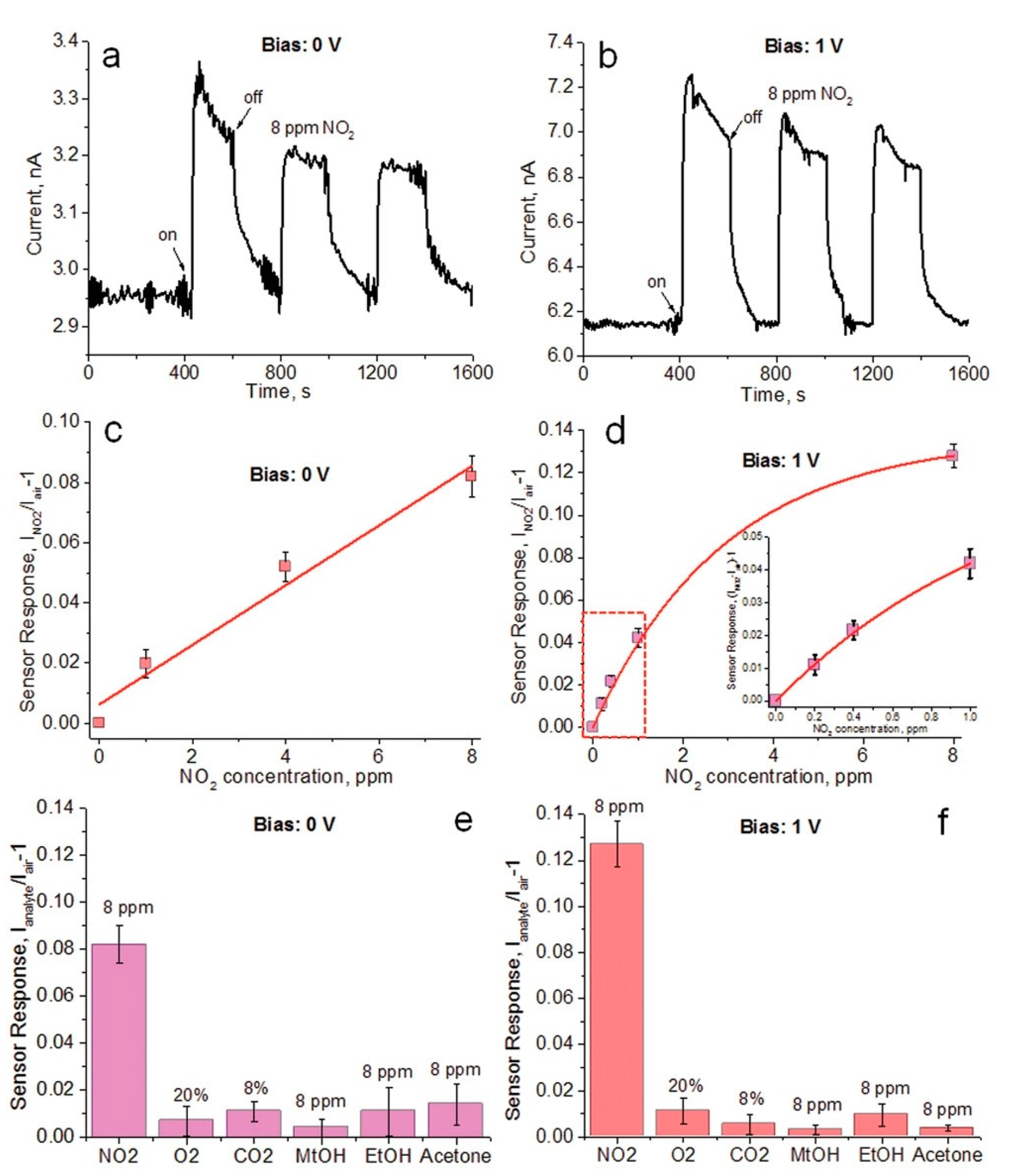

- Fu, X.; Jiao, S.; Dong, N.; Lian, G.; Zhao, T.; Lv, S.; Wang, Q.; Cui, D. A CH3NH3PbI3 film for a room-temperature NO2 gas sensor with quick response and high selectivity. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, H.; Wang, X.; Xiao, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, X. High-performance room-temperature NO2 sensors based on CH3NH3PbBr3 semiconducting films: Effect of surface capping by alkyl chain on sensor performance. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2019, 129, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, V.X.; Hung, P.T.; Han, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.-H.; Heo, Y.-W. Growth and gas sensing properties of methylammonium tin iodide thin film. Scr. Mater. 2020, 178, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Xing, B.; Fu, X.; Bo, R.; Mulmudi, H.K.; Huang, S.; Ho-Baillie, A.W.Y.; Catchpole, K.R.; Tricoli, A. Superior Self-Charged and -Powered Chemical Sensing with High Performance for NO2 Detection at Room Temperature. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2020, 8, 1901863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeckel, M.-A.; Gobbi, M.; Bonacchi, S.; Liscio, F.; Ferlauto, L.; Orgiu, E.; Samorì, P. Reversible, Fast, and Wide-Range Oxygen Sensor Based on Nanostructured Organometal Halide Perovskite. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1702469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kakavelakis, G.; Gagaoudakis, E.; Petridis, K.; Petromichelaki, V.; Binas, V.; Kiriakidis, G.; Kymakis, E. Solution Processed CH3NH3PbI3–xClx Perovskite Based Self-Powered Ozone Sensing Element Operated at Room Temperature. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gagaoudakis, E.; Panagiotopoulos, A.; Maksudov, T.; Moschogiannaki, M.; Katerinopoulou, D.; Kakavelakis, G.; Kiriakidis, G.; Binas, V.; Kymakis, E.; Petridis, K. Self-powered, flexible and room temperature operated solution processed hybrid metal halide p-type sensing element for efficient hydrogen detection. J. Phys. Mater. 2020, 3, 014010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansode, U.; Ogale, S. On-axis pulsed laser deposition of hybrid perovskite films for solar cell and broadband photo-sensor applications. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 121, 133107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Yuan, J.-H.; Luo, J.; Pan, W.; Wu, H.; Chen, Q.; Xue, K.-H.; Miao, X.; Niu, G.; Tang, J. Two-dimensional perovskites as sensitive strain sensors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 3814–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, R.; Pu, L.; Maheshwari, V. A Light Harvesting, Self-Powered Monolith Tactile Sensor Based on Electric Field Induced Effects in MAPbI3 Perovskite. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1705778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, R.; Tsui, T.; Maheshwari, V. Modulation of mechanical properties and stable light energy harvesting by poling in polymer integrated perovskite films: A wide range, linear and highly sensitive tactile sensor. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 14192–14198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yi, J. One-pot electrospinning and gas-sensing properties of LaMnO3 perovskite/SnO2 heterojunction nanofibers. J. Nanopart. Res. 2018, 20, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, R.; Lou, Z.; Deng, J.; Lu, G.; Wang, L. Constructing p–n heterostructures for efficient structure–driven ethanol sensing performance. Sens. Actuators B 2018, 255, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Q. Near-Room-Temperature Ethanol Gas Sensor Based on Mesoporous Ag/Zn–LaFeO3 Nanocomposite. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 6, 1801453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, N.; Ruan, S.; Yin, Y.; Li, F.; Wen, S.; Chen, Y. Self-Sacrificial Template-Driven LaFeO3/α-Fe2O3 Porous Nano-Octahedrons for Acetone Sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 4671–4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-Y.; Jang, J.-S.; Koo, W.-T.; Seo, J.; Choi, Y.; Kim, M.-H.; Kim, D.-H.; Cho, H.-J.; Jung, W.; Kim, I.-D. Perovskite La0.75Sr0.25Cr0.5Mn0.5O3−δ sensitized SnO2 fiber-in-tube scaffold: Highly selective and sensitive formaldehyde sensing. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 10543–10551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, M. Construction of flower-like ZnSnO3/Zn2SnO4 hybrids for enhanced phenylamine sensing performance. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 2311–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zou, H.; Peng, J.; Duan, Z.; Ma, M.; Xin, X.; Li, W.; Zheng, X. Enhanced humidity sensing properties of SmFeO3-modified MoS2 nanocomposites based on the synergistic effect. Sens. Actuators B 2018, 272, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-J.; Baltrus, J.P.; Gao, H.; Ding, Y.; Nam, C.-Y.; Ohodnicki, P.; Gao, P.-X. Perovskite Nanoparticle-Sensitized Ga2O3 Nanorod Arrays for CO Detection at High Temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 8880–8887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Ippolito, S.J.; Periasamy, S.; Sabri, Y.M.; Sunkara, M.V. Efficient Heterostructures of Ag@CuO/BaTiO3 for Low-Temperature CO2 Gas Detection: Assessing the Role of Nanointerfaces during Sensing by Operando DRIFTS Technique. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 27014–27026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Antolasic, F.; Sunkara, M.V.; Bhargava, S.K.; Ippolito, S.J. Highly Selective CO2 Gas Sensing Properties of CaO-BaTiO3 Heterostructures Effectuated through Discretely Created n-n Nanointerfaces. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4086–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Canjeevaram Balasubramanyam, R.K.; Ippolito, S.J.; Sabri, Y.M.; Kandjani, A.E.; Bhargava, S.K.; Sunkara, M.V. Straddled Band Aligned CuO/BaTiO3 Heterostructures: Role of Energetics at Nanointerface in Improving Photocatalytic and CO2 Sensing Performance. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 3375–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.-T.; Dastan, D.; Wu, F.-Y.; Li, J. Facile Synthesis of SnO2/LaFeO3−XNX Composite: Photocatalytic Activity and Gas Sensing Performance. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, B.; Lin, H.-J.; Gao, H.; Lu, X.; Nam, C.-Y.; Gao, P.-X. Perovskite-sensitized β-Ga2O3 nanorod arrays for highly selective and sensitive NO2 detection at high temperature. J. Mater.Chem. A 2020, 8, 10845–10854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ads, E.H.; Atta, N.F.; Galal, A.; El-Gohary, A.R.M. Nano-perovskite decorated carbon nanotubes composite for ultrasensitive determination of a cardio-stimulator drug. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2018, 816, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alluri, N.R.; Purusothaman, Y.; Chandrasekhar, A.; Kim, S.-J. Self-powered wire type UV sensor using in-situ radial growth of BaTiO3 and TiO2 nanostructures on human hair sized single Ti-wire. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 1729–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ding, G.; Mao, J.-Y.; Zhou, Y.; Han, S.-T. Recent advances in synthesis and application of perovskite quantum dot based composites for photonics, electronics and sensors. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2020, 21, 278–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, J.; Cai, J.; Zhu, J.; Yang, X.; Shen, J.; Li, C. Perovskite quantum dots encapsulated in electrospun fiber membranes as multifunctional supersensitive sensors for biomolecules, metal ions and pH. Nanoscale Horiz. 2017, 2, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Xia, Z. Encapsulation of CH3NH3PbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dots in MOF-5 Microcrystals as a Stable Platform for Temperature and Aqueous Heavy Metal Ion Detection. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 4613–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, M.; Geske, T.; Davis, M.; Hao, A.; Wang, H.; Yu, Z. Porous Halide Perovskite–Polymer Nanocomposites for Explosive Detection with a High Sensitivity. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 6, 1801686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova-Cháfer, J.; García-Aboal, R.; Atienzar, P.; Llobet, E. Gas Sensing Properties of Perovskite Decorated Graphene at Room Temperature. Sensors 2019, 19, 4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Zhao, H.; Wang, X.; Xu, J. Effects of organotin halide perovskite and Pt nanoparticles in SnO2-based sensing materials on the detection of formaldehyde. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 20624–20637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

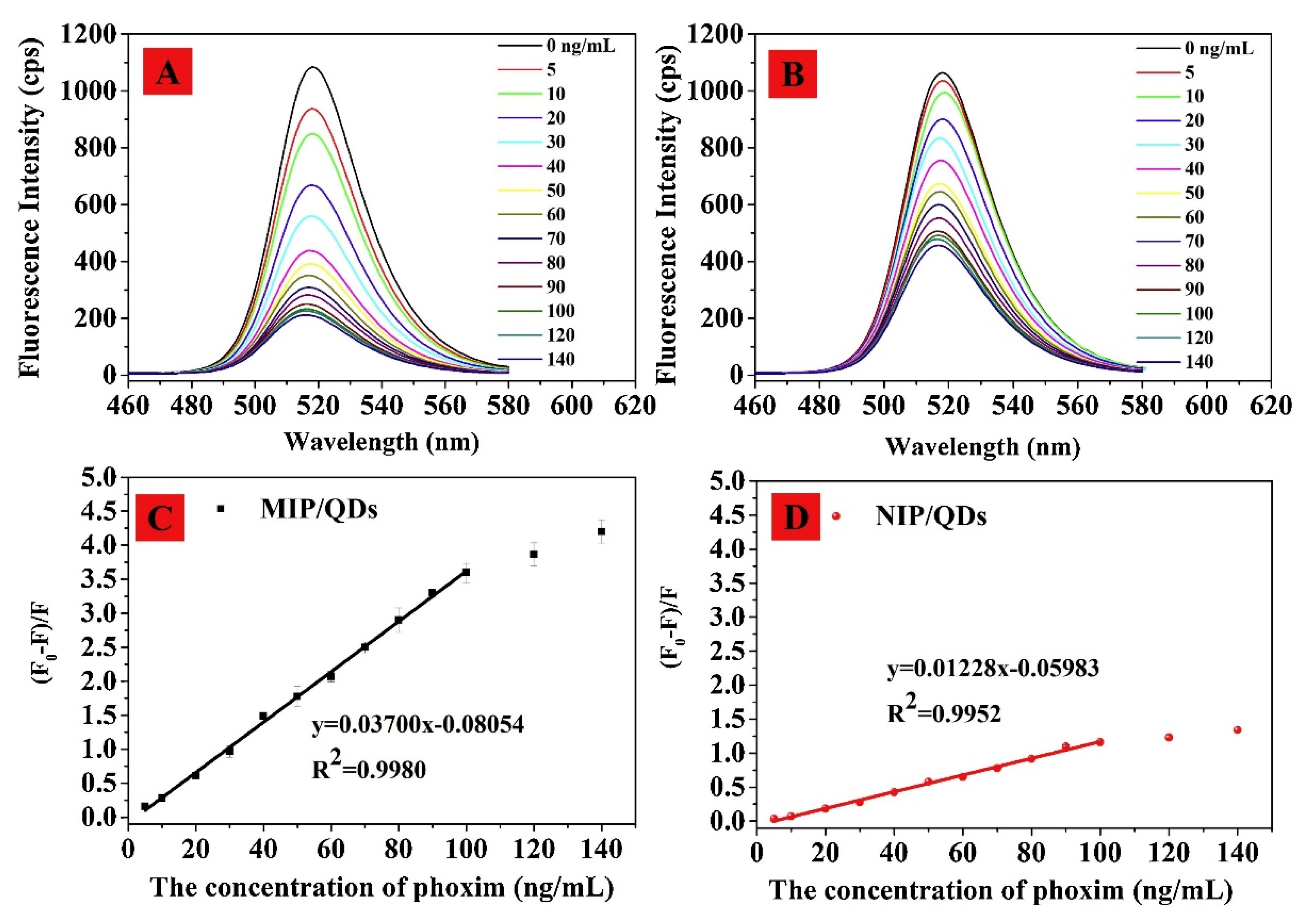

- Huang, S.; Guo, M.; Tan, J.; Geng, Y.; Wu, J.; Tang, Y.; Su, C.; Lin, C.C.; Liang, Y. Novel Fluorescence Sensor Based on All-Inorganic Perovskite Quantum Dots Coated with Molecularly Imprinted Polymers for Highly Selective and Sensitive Detection of Omethoate. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 39056–39063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Guo, M.; Tan, J.; Geng, Y.; Huang, S.; Tang, Y.; Su, C.; Lin, C.; Liang, Y. Development of high-luminescence perovskite quantum dots coated with molecularly imprinted polymers for pesticide detection by slowly hydrolysing the organosilicon monomers in situ. Sens. Actuators B 2019, 291, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, D.; Pan, G.; Zhou, D.; Xu, W.; Zhu, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, C.; Song, H. All-inorganic perovskite quantum dot/TiO2 inverse opal electrode platform: Stable and efficient photoelectrochemical sensing of dopamine under visible irradiation. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 10505–10513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaou, P.; Vassilakopoulou, A.; Papadatos, D.; Topoglidis, E.; Koutselas, I. A chemical sensor for CBr4 based on quasi-2D and 3D hybrid organic–inorganic perovskites immobilized on TiO2 films. Mater. Chem. Front. 2018, 2, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, L.; Xiong, X.; Shu, Y.; Jin, D.; Zang, Y.; Wang, W.; Xu, Q.; Hu, X.-Y. Molecularly imprinted polymers and PEG double engineered perovskite: An efficient platform for constructing aqueous solution feasible photoelectrochemical sensor. Sens. Actuators B 2020, 304, 127321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

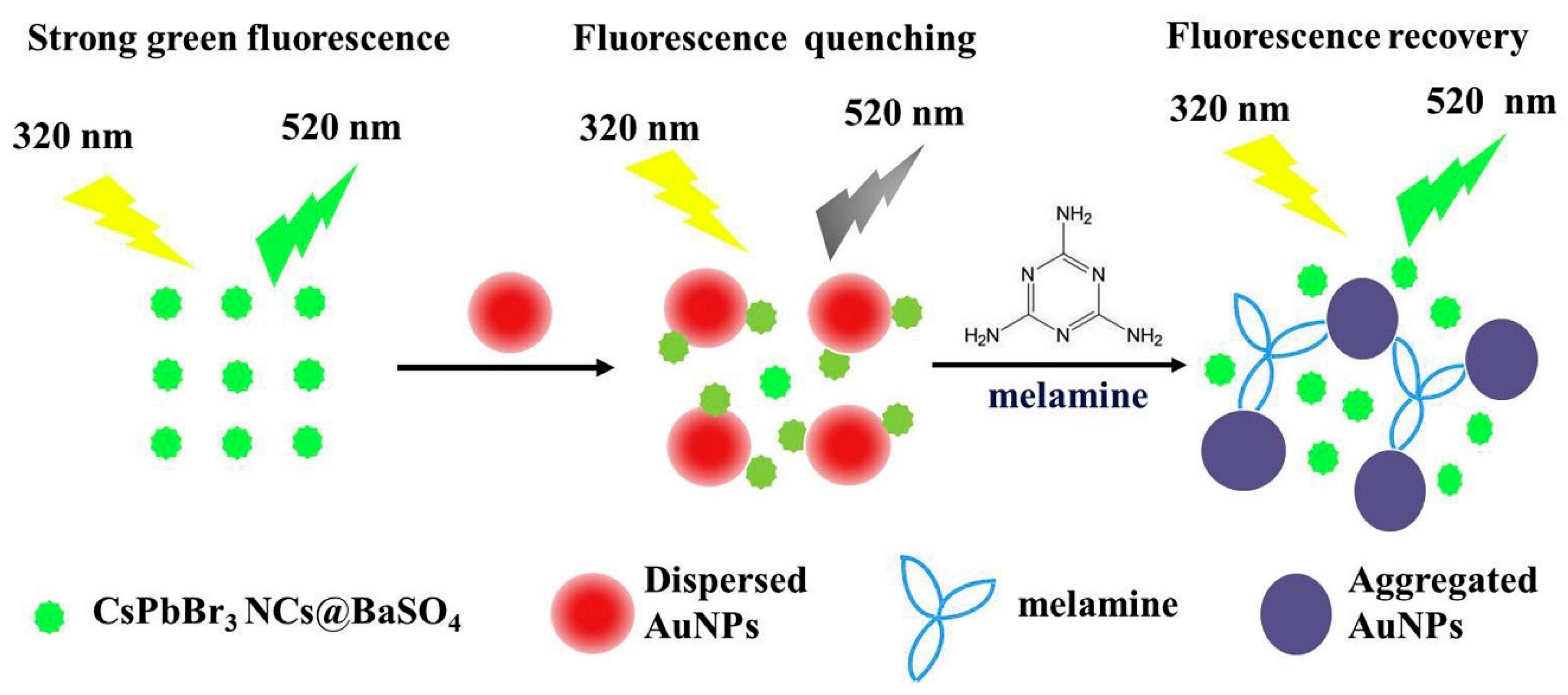

- Li, Q.; Wang, H.; Yue, X.; Du, J. Perovskite nanocrystals fluorescence nanosensor for ultrasensitive detection of trace melamine in dairy products by the manipulation of inner filter effect of gold nanoparticles. Talanta 2020, 211, 120705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zu, Z.; Zang, Z.; Hu, Z.; Hu, W.; Yao, Z.; Chen, W.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Zhou, M. CsPbBr3/Reduced Graphene Oxide nanocomposites and their enhanced photoelectric detection application. Sens. Actuators B 2017, 245, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; Zhou, Z.; Xuan, T.; Li, H.; Jiao, J.; Zhang, H.; Gautier, R.; Wang, J. Chemical Transformation of Lead Halide Perovskite into Insoluble, Less Cytotoxic, and Brightly Luminescent CsPbBr3/CsPb2Br5 Composite Nanocrystals for Cell Imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 24241–24246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, D.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Nalla, V.; Zeng, H.; Sun, H. Solution-Grown CsPbBr3/Cs4PbBr6 Perovskite Nanocomposites: Toward Temperature-Insensitive Optical Gain. Small 2017, 13, 1701587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Li, F.; Jin, J.; Dong, J.; Lin, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X. Dual-Mode of Fluorescence Turn-On and Wavelength-Shift for Methylamine Gas Sensing Based on Space-Confined Growth of Methylammonium Lead Tribromide Perovskite Nanocrystals. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 5661–5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jacky, E.; Soline, B.-R.; Marcelo, C.; Laurent, P.; Jean-Marc, J.; Claudine, K. Theoretical insights into hybrid perovskites for photovoltaic applications. Proc. SPIE 2016, 9742, 97421A. [Google Scholar]

- Brakkee, R.; Williams, R.M. Minimizing Defect States in Lead Halide Perovskite Solar Cell Materials. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dan, Y.; Dong, R.; Cao, Z.; Niu, C.; Song, Y.; Li, S.; Hu, J. Computational Screening of New Perovskite Materials Using Transfer Learning and Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tripathi, K.M.; Kim, T.; Losic, D.; Tung, T.T. Recent advances in engineered graphene and composites for detection of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and non-invasive diseases diagnosis. Carbon 2016, 110, 97–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, K.M.; Sachan, A.; Castro, M.; Choudhary, V.; Sonkar, S.K.; Feller, J.F. Green carbon nanostructured quantum resistive sensors to detect volatile biomarkers. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2018, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G.S.; Shim, J.P.; Bhatnagar, A.; Tripathi, K.M.; Kim, T. Biomass-derived Carbon Quantum Dots for Visible-Light-Induced Photocatalysis and Label-Free Detection of Fe(III) and Ascorbic acid. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, N.; Kumari, A.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, T.; Tripathi, K.M. Nano-carbon based sensors for bacterial detection and discrimination in clinical diagnosis: A junction between material science and biology. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 18, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shellaiah, M.; Sun, K.W. Review on Sensing Applications of Perovskite Nanomaterials. Chemosensors 2020, 8, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors8030055

Shellaiah M, Sun KW. Review on Sensing Applications of Perovskite Nanomaterials. Chemosensors. 2020; 8(3):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors8030055

Chicago/Turabian StyleShellaiah, Muthaiah, and Kien Wen Sun. 2020. "Review on Sensing Applications of Perovskite Nanomaterials" Chemosensors 8, no. 3: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors8030055

APA StyleShellaiah, M., & Sun, K. W. (2020). Review on Sensing Applications of Perovskite Nanomaterials. Chemosensors, 8(3), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors8030055