The Effects of Financial Stress and Household Socio-Economic Deprivation on the Malnutrition Statuses of Children under Five during the COVID-19 Lockdown in a Marginalized Region of South Punjab, Pakistan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

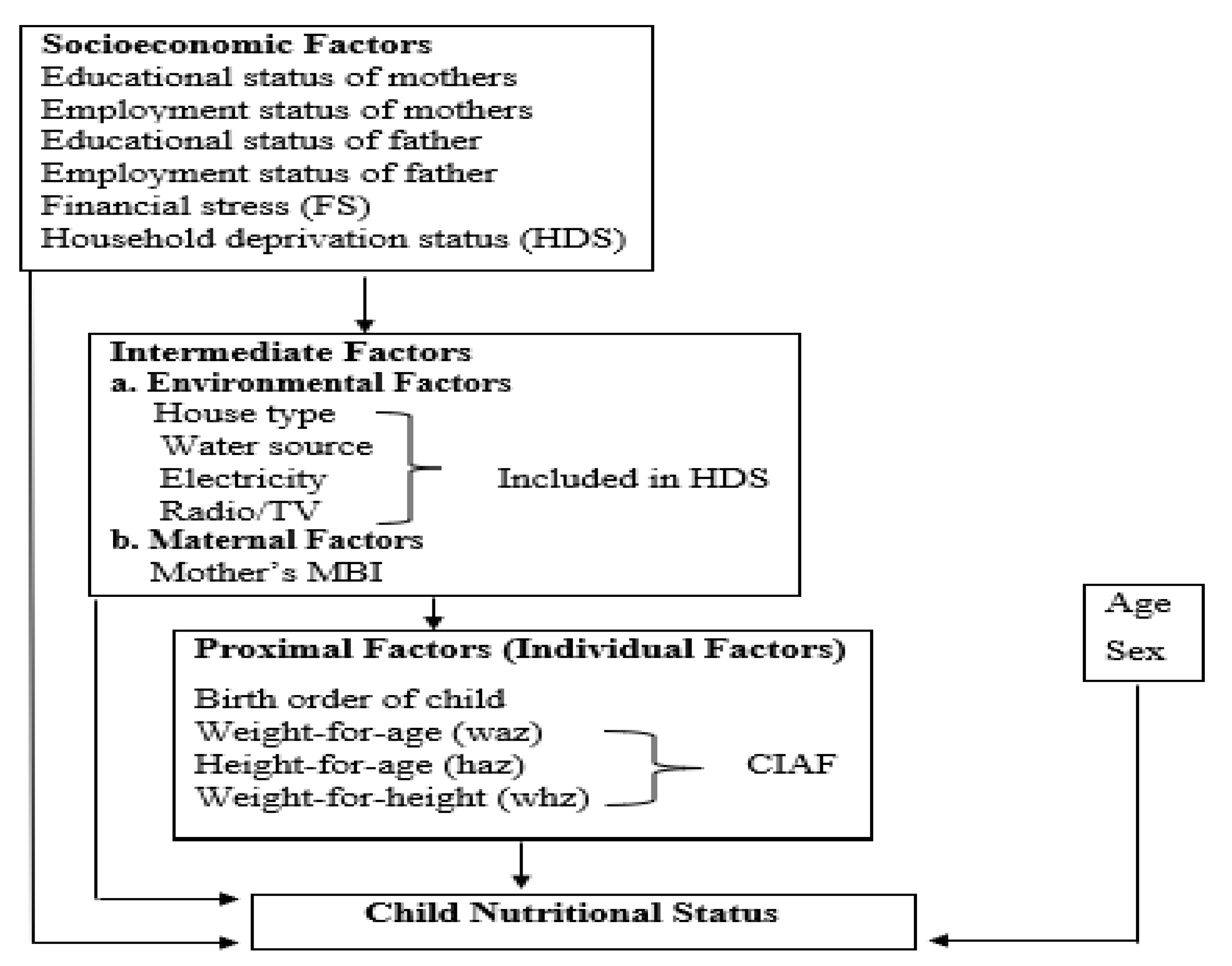

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

3. Methods

3.1. Participants in the Study and the Eligibility Criteria

3.2. Research Area, Sample Design, and Data Collection

3.3. Outcome Variable

3.4. Measures

3.5. Statistical Analysis

3.6. Ethical Consideration

4. Results

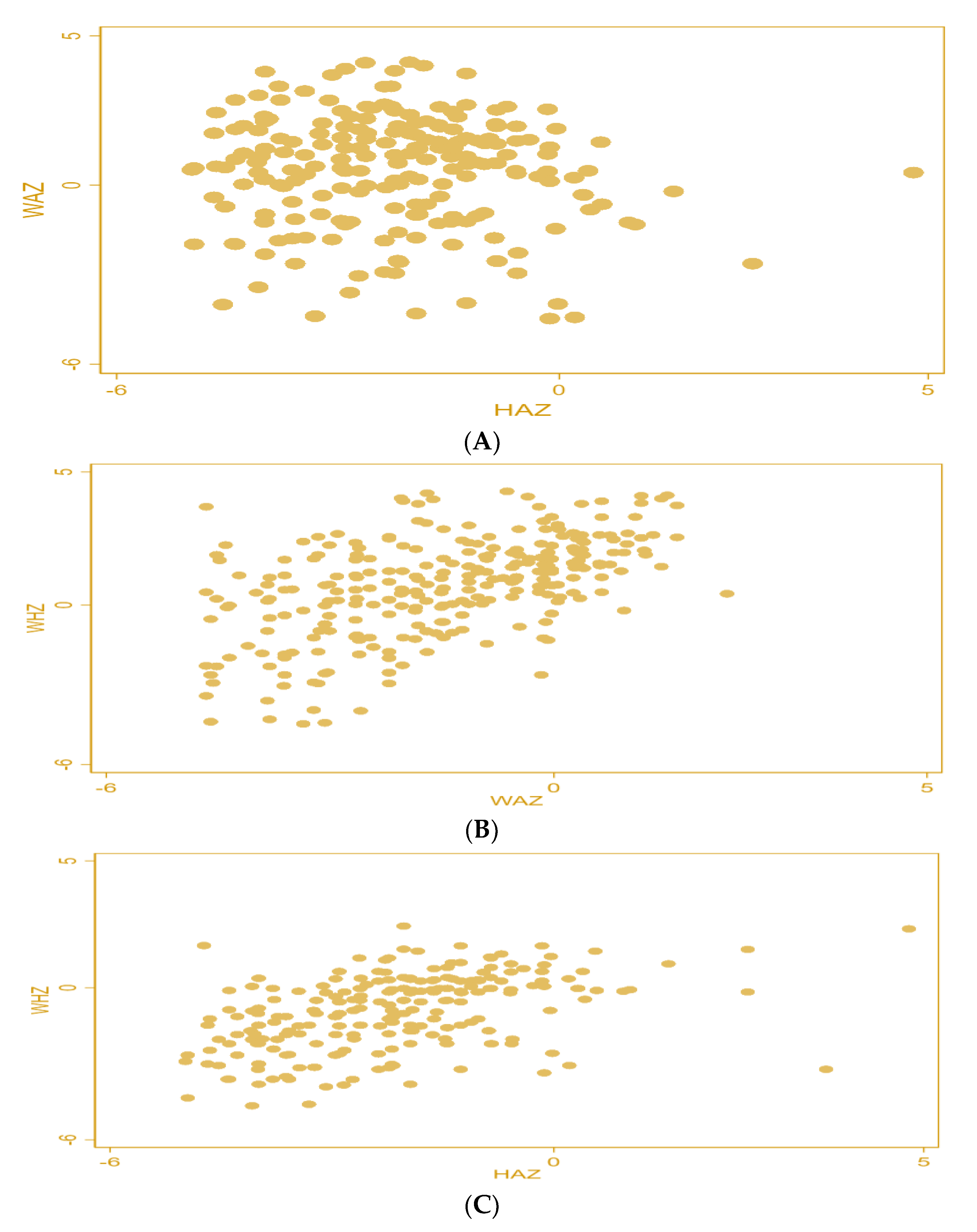

4.1. Distribution of Data

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Estimates of Logistic Regression

5. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qureshi, M.G.; Shahid, M.; Ahmed, F.; Rafiq, S.; Malik, N.I. Congregational Religious Prayers amid Covid-19 and Pandemic Spread—Evidence from Southern Punjab, Pakistan. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2021, 9, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, D.H.B.; Narayan, P.K. Country responses and the reaction of the stock market to COVID-19—A preliminary exposition. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 2020, 56, 2138–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Chen, X.; Shi, W. Impacts of social and economic factors on the transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. J. Popul. Econ. 2020, 33, 1127–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.; Silva, R.; Franco, M. COVID-19: Financial Stress and Well-Being in Families. J. Fam. Issues. 2021, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodeur, A.; Gray, D.; Islam, A.; Bhuiyan, S. A literature review of the economics of COVID-19. J. Econ. Surv. 2021, 35, 1007–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.; Gardiner, L. The initial impact of COVID-19 and policy responses on household incomes. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2020, 36, S187–S199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntambara, J.; Chu, M. The risk to child nutrition during and after COVID-19 pandemic: What to expect and how to respond. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 3530–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fore, H.H.; Dongyu, Q.; Beasley, D.M.; Ghebreyesus, T.A. Child malnutrition and COVID-19: The time to act is now. Lancet 2020, 396, 517–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akseer, N.; Kandru, G.; Keats, E.C.; Bhutta, Z.A. COVID-19 pandemic and mitigation strategies: Implications for maternal and child health and nutrition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayatissa, R.; Herath, H.P.; Perera, A.G.; Dayaratne, T.T.; De Alwis, N.D.; Nanayakkara, H.P.L.K. Impact of COVID-19 on child malnutrition, obesity in women and household food insecurity in underserved urban settlements in Sri Lanka: A prospective follow-up study. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 3233–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, E.; Peñalvo, J.L. The burden of malnutrition and fatal COVID-19: A global burden of disease analysis. Front. Nutr. 2021, 7, 619850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlejohn, P.; Finlay, B.B. When a pandemic and an epidemic collide: COVID-19, gut microbiota, and the double burden of malnutrition. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.V.; Chuang, R.J.; Rushing, M.; Naylor, B.; Ranjit, N.; Pomeroy, M.; Markham, C. Peer reviewed: Social determinants of health–related needs during COVID-19 among low-income households with children. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, E119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osendarp, S.; Akuoku, J.K.; Black, R.E.; Headey, D.; Ruel, M.; Scott, N.; Shekar, M.; Walker, N.; Flory, A.; Haddad, L.; et al. The COVID-19 crisis will exacerbate maternal and child undernutrition and child mortality in low-and middle-income countries. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loperfido, L.; Burgess, M.; Arlini, S.M. The Hidden Impact of COVID-19 on Child Poverty; Save the Children International: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition (FSN); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Niles, M.T.; Bertmann, F.; Belarmino, E.H.; Wentworth, T.; Biehl, E.; Neff, R. The Early Food Insecurity Impacts of COVID-19. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headey, D.; Heidkamp, R.; Osendarp, S.; Ruel, M.; Scott, N.; Black, R.; Shekar, M.; Bouis, H.; Flory, A.; Haddad, L.; et al. Impacts of COVID-19 on childhood malnutrition and nutrition-related mortality. Lancet 2020, 396, 519–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headey, D.D.; Ruel, M.T. The COVID-19 nutrition crisis: What to expect and how to protect. In COVID-19 and Global Food Security; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tester, J.M.; Rosas, L.G.; Leung, C.W. Food insecurity and pediatric obesity: A double whammy in the era of COVID-19. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2020, 9, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Pulse Survey on Continuity of Essential Health Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Interim Report. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-%20nCoV-EHS_continuity-survey-2020.1 (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- UNICEF & WFP. Nutrition Crisis Looms as More than 39 Billion In-School Meals Missed Since Start of Pandemic. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eap/press-releases/nutrition-crisis-looms-more-39-billion-school-meals-missed-start-pandemic-unicef-and#:~:text=NEW%20YORK%2FROME%2C%2028%20January,World%20Food%20Programme%20(WFP) (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Rasheed, R.; Rizwan, A.; Javed, H.; Sharif, F.; Zaidi, A. Socio-economic and environmental impacts of COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan—An integrated analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 19926–19943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, W.; Cho, S.H.; Lee, P. APR Financial Stress Scale: Development and validation of a multidimensional measurement. J. Financ. Ther. 2020, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, P.D.; Buklijas, T.; Hanson, M.A. The developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) concept: Past, present, and future. In The Epigenome and Developmental Origins of Health and Disease; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pooler, J.; Perry, D.F.; Ghandour, R.M. Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms among women enrolled in WIC. Matern. Child Health J. 2013, 17, 1969–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. A Theory of the Allocation of Time. Econ. J. 1965, 75, 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, J.; Thomas, D. Human Resources: Empirical Modeling of Household and Family Decisions. In Handbook of Development Economics; Behrman, J.B., Srinivasan, T.N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; Volume 3, pp. 1883–2023. [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C.G.; Huttly, S.R.; Fuchs, S.C.; Olinto, M.T. The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: A hierarchical approach. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 26, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Child Growth Standards and the Identification of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Infants and Children: A Joint Statement by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund, Geneva; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, K.; Mohanty, S.K. Household deprivation and its linkages with reproductive health utilisation. Econ. Political Wkly. 2008, 43, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M.; Cao, Y.; Ahmed, F.; Raza, S.; Guo, J.; Malik, N.I.; Rauf, U.; Qureshi, M.G.; Saheed, R.; Maryam, R. Does Mothers’ Awareness of Health and Nutrition Matter? A Case Study of Child Malnutrition in Marginalized Rural Community of Punjab, Pakistan. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 792164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawaregowda, S.K.; Angadi, M.M. Gender differences in nutritional status among under-five children in rural areas of Bijapur district, Karnataka, India. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2015, 2, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dhungana, G.P. Nutritional Status and the Associated Factors in Under Five Years Children of Lamjung, Gorkha and Tanahun Districts of Nepal. Nep. J. Stat. 2017, 1, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haq, I.; Hossain, M.I.; Parvin, M.M.; Saleheen, A.A.S.; Habib, M.J. Gender differences in child nutrition status of Bangladesh: A multinomial modeling approach. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 4, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Saheed, R.; Wang, J.; Qureshi, M.G.; Sun, X.; Bibi, A.; Zia, S.; Tang, K. Impact of Drinking Water Source and Sanitation Facility on Malnutrition Prevalence in Children under Three: A Gender-Disaggregated Analysis Using PDHS 2017–18. Children 2022, 9, 1674. [Google Scholar]

- Jayachandran, S.; Kuziemko, I. Why do mothers breastfeed girls less than boys? Evidence and implications for child health in India. Q. J. Econ. 2011, 126, 1485–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arif, G.M.; Nazir, S.; Satti, M.N.; Farooq, S. Child malnutrition in Pakistan: Trends and determinants. Pak. Inst. Dev. Econ. 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Heise, L.; Greene, M.E.; Opper, N.; Stavropoulou, M.; Harper, C.; Nascimento, M.; Zewdie, D.; Darmstadt, G.L.; Greene, M.E.; Hawkes, S. Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: Framing the challenges to health. Lancet 2019, 393, 2440–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, E.A.; Raza, M.A. Nutritional status of children in Bangladesh: Measuring composite index of anthropometric failure (CIAF) and its determinants. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2014, 8, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, P.; Headey, D.; Avula, R.; Nguyen, P.H. Understanding the geographical burden of stunting in India: A regression-decomposition analysis of district-level data from 2015–16. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14, e12620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.; Ohuma, E.; Ariana, P.; Webster, P.; Gray, R. Effect of the Mahatma Gandhi national rural employment guarantee act on malnutrition of children aged between 1 and 12 months in Rajasthan, India: A mixed methods study. Lancet 2012, 380, S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M. Interaction of Household Wealth and Women’s Working Status on Child Malnutrition: Evidence from PDHS-2013. Pak. Perspect. 2020, 25, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravana, N.K.; Piryani, S.; Chaurasiya, S.P.; Kawan, R.; Thapa, R.K.; Shrestha, S. Determinants of severe acute malnutrition among children under 5 years of age in Nepal: A community-based case–control study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tariq, J.; Sajjad, A.; Zakar, R.; Zakar, M.Z.; Fischer, F. Factors associated with undernutrition in children under the age of two years: Secondary data analysis based on the Pakistan demographic and health survey 2012–2013. Nutrients 2018, 10, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Srinivasan, K.; Mohanty, S.K. of Basic Amenities Deprivation and by Caste Religion Empirical. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2004, 39, 728–735. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton, R.J.; Elia, M. Deprivation linked to malnutrition risk and mortality in hospital. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 96, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rabbani, A.; Khan, A.; Yusuf, S.; Adams, A. Trends and determinants of inequities in childhood stunting in Bangladesh from 1996/7 to 2014. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ortiz, J.; Van Camp, J.; Wijaya, S.; Donoso, S.; Huybregts, L. Determinants of child malnutrition in rural and urban Ecuadorian highlands. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2122–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Armstrong, J.; Dorosty, A.R.; Reilly, J.J.; Emmett, P.M. Coexistence of social inequalities in undernutrition and obesity in preschool children: Population based cross sectional study. Arch. Dis. Childh. 2003, 88, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fotso, J.C.; Madise, N.; Baschieri, A.; Cleland, J.; Zulu, E.; Mutua, M.K.; Essendi, H. Child growth in urban deprived settings: Does household poverty status matter? At which stage of child development? Health Place 2012, 18, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lubna, N.; Kamalesh, K.P.; Ifeoma, E.U. The prevalence of undernutrition and associated factors among preschool children: Evidence from Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105579. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M.; Ahmed, F.; Ameer, W.; Guo, J.; Raza, S.; Fatima, S.; Qureshi, G.M. Prevalence of child malnutrition and household socioeconomic deprivation: A case study of marginalized district in Punjab, Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raviv, T.; Wadsworth, M.E. The efficacy of a pilot prevention program for children and caregivers coping with economic strain. Cognitive Ther. Res. 2010, 34, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemrani, B.; Gehri, M.; Masserey, E.; Knob, C.; Pellaton, R. A hidden side of the COVID-19 pandemic in children: The double burden of undernutrition and overnutrition. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, T.J.; MacGillivray, S.A.; Reid, I.C.; Cameron, I.M. Psychometric properties of the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 60, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L.M.; Litt, D.M.; Stewart, S.H. COVID-19 psychological and financial stress and their links to drinking: A dyadic analysis in romantic couples. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2021, 35, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robillard, R.; Saad, M.; Edwards, J.; Solomonova, E.; Pennestri, M.H.; Daros, A.; Kendzerska, T. Social, financial and psychological stress during an emerging pandemic: Observations from a population survey in the acute phase of COVID-19. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e043805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, N.; Sadowski, A.; Laila, A.; Hruska, V.; Nixon, M.; Ma, D.W.L.; Haines, J.; on behalf of the Guelph Family Health Study. The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Behavior, Stress, Financial and Food Security among Middle to High Income Canadian Families with Young Children. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamberi, E.; Martinovic, B.; Verkuyten, M. Life satisfaction and happiness among the Roma in Central and Southeastern Europe. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 124, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, W.J.; Xu, Z. Economic stress, quality of life, and mortality for the oldest old in China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 108, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, S.; Lim, H.; Montalto, C. Factors Related to Financial Stress among College Students. J. Financ. Ther. 2014, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thayer, Z.M.; Gildner, T.E. COVID-19-related financial stress associated with higher likelihood of depression among pregnant women living in the United States. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2021, 33, e23508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, L.; Cruz, V.; Frederick, D.; Herrera, S. Financial stress among Latino Adults in California during COVID-19. J. Econ. Race Policy 2022, 5, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Stevens, G.; Agho, K.; Raphael, B. The impacts of household financial stress, resilience, social support, and other adversities on the psychological distress of Western Sydney parents. Int. J. Popul. Res. 2017, 2017, 6310683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloud, T.; Bann, D. Financial stress and mental health among higher education students in the UK up to 2018: Rapid review of evidence. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2019, 73, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fox, J.; Bartholomae, S. Household finances, financial planning, and COVID-19. Financ. Plan. Rev. 2020, 3, e1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedline, T.; Chen, Z.; Morrow, S.P. Families’ financial stress & well-being: The importance of the economy and economic environments. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021, 42, 34–51. [Google Scholar]

- Adegboye, D.; Williams, F.; Collishaw, S.; Shelton, K.; Langley, K.; Hobson, C.; van Goozen, S. Understanding why the COVID-19 pandemic-related lockdown increases mental health difficulties in vulnerable young children. JCPP Adv. 2021, 1, e12005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Division /Region | Districts | Tehsils | Council Union Number | Proportionate Sample/HH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahawalpur | 1. Rahimyar Khan District Sample = 384 (100%) | Khanpur Sample = 96 | UC1 | 26 |

| UC2 | 34 | |||

| UC3 | 36 | |||

| Liaquatpur Sample = 81 | UC4 | 25 | ||

| UC5 | 26 | |||

| UC6 | 30 | |||

| Rahimyar Khan Sample = 115 | UC7 | 34 | ||

| UC8 | 46 | |||

| UC9 | 35 | |||

| Sadiqabad Sample = 92 | UC10 | 33 | ||

| UC11 | 32 | |||

| UC12 | 27 | |||

| 2. Bahawalpur District Sample = 384 (100%) | Bahawalpur Sample = 111 | UC13 | 29 | |

| UC14 | 39 | |||

| UC15 | 43 | |||

| Hasilpur Sample = 65 | UC16 | 27 | ||

| UC17 | 11 | |||

| UC18 | 27 | |||

| Khairpur Tamewali Sample = 54 | UC19 | 18 | ||

| UC20 | 23 | |||

| UC21 | 13 | |||

| Yazman Sample = 77 | UC22 | 10 | ||

| UC23 | 41 | |||

| UC24 | 26 | |||

| Ahmad Pur East Sample = 77 | UC25 | 36 | ||

| UC26 | 20 | |||

| UC27 | 21 | |||

| 3. Bahawalnagar District Sample = 384 (100%) | Bahawalnagar Sample = 100 | UC28 | 37 | |

| UC29 | 48 | |||

| UC30 | 15 | |||

| Chishtian Sample = 92 | UC31 | 20 | ||

| UC32 | 54 | |||

| UC33 | 14 | |||

| Fort Abbas Sample = 54 | UC34 | 7 | ||

| UC35 | 23 | |||

| UC36 | 26 | |||

| Haroonabad Sample = 73 | UC37 | 55 | ||

| UC38 | 12 | |||

| UC39 | 7 | |||

| Minchinabad Sample = 65 | UC40 | 10 | ||

| UC41 | 27 | |||

| UC42 | 29 | |||

| Districts = 3 | Tehsils = 14 | Total UCs = 42 | HH = 1152 |

| Indicators | Stunting (n = 948) | Underweight (n = 1368) | Wasting (n = 1221) | CIAF (n = 930) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Male | 264 | 47.31 | 300 | 52.36 | 57 | 57.58 | 279 | 47.45 |

| Female | 294 | 52.69 | 273 | 47.64 | 42 | 42.42 | 309 | 52.55 |

| Total | 558 | 58.86 | 573 | 41.89 | 99 | 8.11 | 588 | 63.23 |

| Indicators | Stunting (n = 948) | Underweight (n = 1368) | Wasting (n = 1221) | CIAF (n = 930) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| 0–12 months | 51 | 9.14 | 105 | 18.32 | 18 | 18.18 | 57 | 9.69 |

| 13–24 months | 78 | 13.98 | 144 | 25.13 | 24 | 24.24 | 78 | 13.27 |

| 25–36 months | 171 | 30.65 | 165 | 28.80 | 18 | 18.18 | 180 | 30.61 |

| 37–48 months | 141 | 25.27 | 105 | 18.32 | 27 | 27.27 | 153 | 26.02 |

| 49–60 months | 117 | 20.97 | 54 | 9.42 | 12 | 12.12 | 120 | 20.41 |

| Total | 558 | 58.86 | 573 | 41.89 | 99 | 8.11 | 588 | 63.23 |

| Stunting | Underweight | Wasting | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan | 38% | 23% | 8% |

| Punjab | 31.5% | 21.2% | 7.5% |

| Bahawalpur Division Before COVID-19 | 41.6% | 29.6% | 8.3% |

| Bahawalpur Division During COVID-19 | 58.86% | 41.89% | 8.11% |

| Variables | Categories | F | % | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Gender | Male | 279 | 47.45 | 0.011 *** |

| Female | 309 | 52.55 | ||

| Child Age (Months) | 0 to 12 | 57 | 9.69 | 0.000 *** |

| 13–24 | 78 | 13.27 | ||

| 25–36 | 180 | 30.61 | ||

| 37–48 | 153 | 26.02 | ||

| 49–60 | 120 | 20.41 | ||

| Number of Order of Birth | Birth order 1 | 165 | 26.53 | 0.000 *** |

| 2 or 3 | 237 | 40.31 | ||

| 4 or 5 | 123 | 20.92 | ||

| 6 or above | 72 | 12.24 | ||

| Mother BMI | Less than 18.5 kg/m2 | 78 | 13.27 | 0.014 *** |

| Equal to or more than 18.5 kg/m2 | 510 | 86.73 | ||

| Education of Mother | No education | 450 | 76.53 | 0.000 *** |

| Primary | 66 | 11.22 | ||

| Middle | 42 | 7.14 | ||

| Matric | 18 | 3.06 | ||

| FA and higher | 12 | 2.04 | ||

| Education of Father | No education | 405 | 68.88 | 0.489 |

| Primary | 105 | 17.86 | ||

| Middle | 21 | 3.57 | ||

| Matric | 48 | 8.16 | ||

| FA and higher | 9 | 1.53 | ||

| Working Status of Mother | Working | 9 | 1.53 | 0.000 *** |

| Not working | 579 | 98.47 | ||

| Working Status of Father | Govt. job | 24 | 4.08 | 0.001 *** |

| Private job | 25 | 4.09 | ||

| Own business | 75 | 12.76 | ||

| Labor or daily wages and agriculture | 465 | 79.08 | ||

| Household Deprivation Status (HDS) | HDS-1 | 15 | 2.55 | 0.017 ** |

| HDS-2 | 552 | 88.78 | ||

| HDS-3 | 51 | 8.67 | ||

| Financial Stress | High-stress | 540 | 91.84 | 0.000 *** |

| Medium-stress | 33 | 5.61 | ||

| Low-stress | 15 | 2.55 |

| Variables | Categories | Odd. Ratios | p-Vales | CI: 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Gender (Female-reference) | Male | 0.72 | 0.04 ** | (0.52–0.98) |

| Age of Child (0 to 12 months-reference) | 13–24 months | 2.52 | 0.006 *** | (1.31–4.87) |

| 25–36 months | 8.43 | 0.000 *** | (4.45–16.03) | |

| 37–48 months | 1.16 | 0.57 | (0.69–1.91) | |

| 49–60 months | 0.94 | 0.82 | (0.56–1.58) | |

| Birth Order Number (Birth order 1-reference) | 2 or 3 | 0.80 | 0.29 | (0.54–1.21) |

| 4 or 5 | 0.47 | 0.000 *** | (0.31–0.71) | |

| 6 or above | 1.18 | 0.56 | (0.67–2.07) | |

| Mother’s BMI (less than 18.5 kg/m2-reference) | Equal to or more than18.5 kg/m2 | 1.45 | 0.08 ** | (0.95–2.21) |

| Education of mother (illiterate-reference) | Primary | 0.86 | 0.81 | (0.24–3.04) |

| Middle | 0.85 | 0.84 | (0.22–3.31) | |

| Matric and higher | 0.32 | 0.14 | (0.07–1.46) | |

| Education of father (illiterate-reference) | Primary | 0.67 | 0.54 | (0.19–2.35) |

| Middle | 2.03 | 0.32 | (0.51–8.11) | |

| Matric and higher | 5.99 | 0.31 | (0.61, 59.29) | |

| Mother’s Working Status (Working-reference) | Not working | 3.14 | 0.09 ** | (0.81–12.18) |

| Working Status of Father (Govt. Job-reference) | Daily wage or labor and agriculture | 0.52 | 0.46 | (0.09–2.95) |

| Private job | 0.18 | 0.05 ** | (0.04–0.96) | |

| Own business | 0.05 | 0.002 *** | (0.007–0.35) | |

| Household Deprivation Status (HDS-1-reference) | HDS-2 | 0.05 | 0.027 ** | (0. 005–0.879) |

| HDS-3 | 0.04 | 0.000 *** | (0.008–0.193) | |

| Financial Stress (High-reference) | Medium | 0.10 | 0.009 *** | (0.018–0.567) |

| Low | 0.006 | 0.000 *** | (0.005–0.061) | |

| The model’s overall significance | ||||

| Number of Observations = 930 | Prob > Chi2 = 0.0000 | |||

| LR Chi2 (26) = 231.56 | Pseudo R2 = 0.1910 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alam, M.B.; Shahid, M.; Alzghoul, B.I.; Yang, J.; Zakar, R.; Malik, N.I.; Bibi, A.; Tang, K. The Effects of Financial Stress and Household Socio-Economic Deprivation on the Malnutrition Statuses of Children under Five during the COVID-19 Lockdown in a Marginalized Region of South Punjab, Pakistan. Children 2023, 10, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10010012

Alam MB, Shahid M, Alzghoul BI, Yang J, Zakar R, Malik NI, Bibi A, Tang K. The Effects of Financial Stress and Household Socio-Economic Deprivation on the Malnutrition Statuses of Children under Five during the COVID-19 Lockdown in a Marginalized Region of South Punjab, Pakistan. Children. 2023; 10(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlam, Muhammad Babar, Muhammad Shahid, Bashar Isam Alzghoul, Juan Yang, Rubeena Zakar, Najma Iqbal Malik, Asma Bibi, and Kun Tang. 2023. "The Effects of Financial Stress and Household Socio-Economic Deprivation on the Malnutrition Statuses of Children under Five during the COVID-19 Lockdown in a Marginalized Region of South Punjab, Pakistan" Children 10, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10010012

APA StyleAlam, M. B., Shahid, M., Alzghoul, B. I., Yang, J., Zakar, R., Malik, N. I., Bibi, A., & Tang, K. (2023). The Effects of Financial Stress and Household Socio-Economic Deprivation on the Malnutrition Statuses of Children under Five during the COVID-19 Lockdown in a Marginalized Region of South Punjab, Pakistan. Children, 10(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10010012