Practice Variation among Pediatric Endocrinologists in the Dosing of Glucocorticoids in Young Children with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

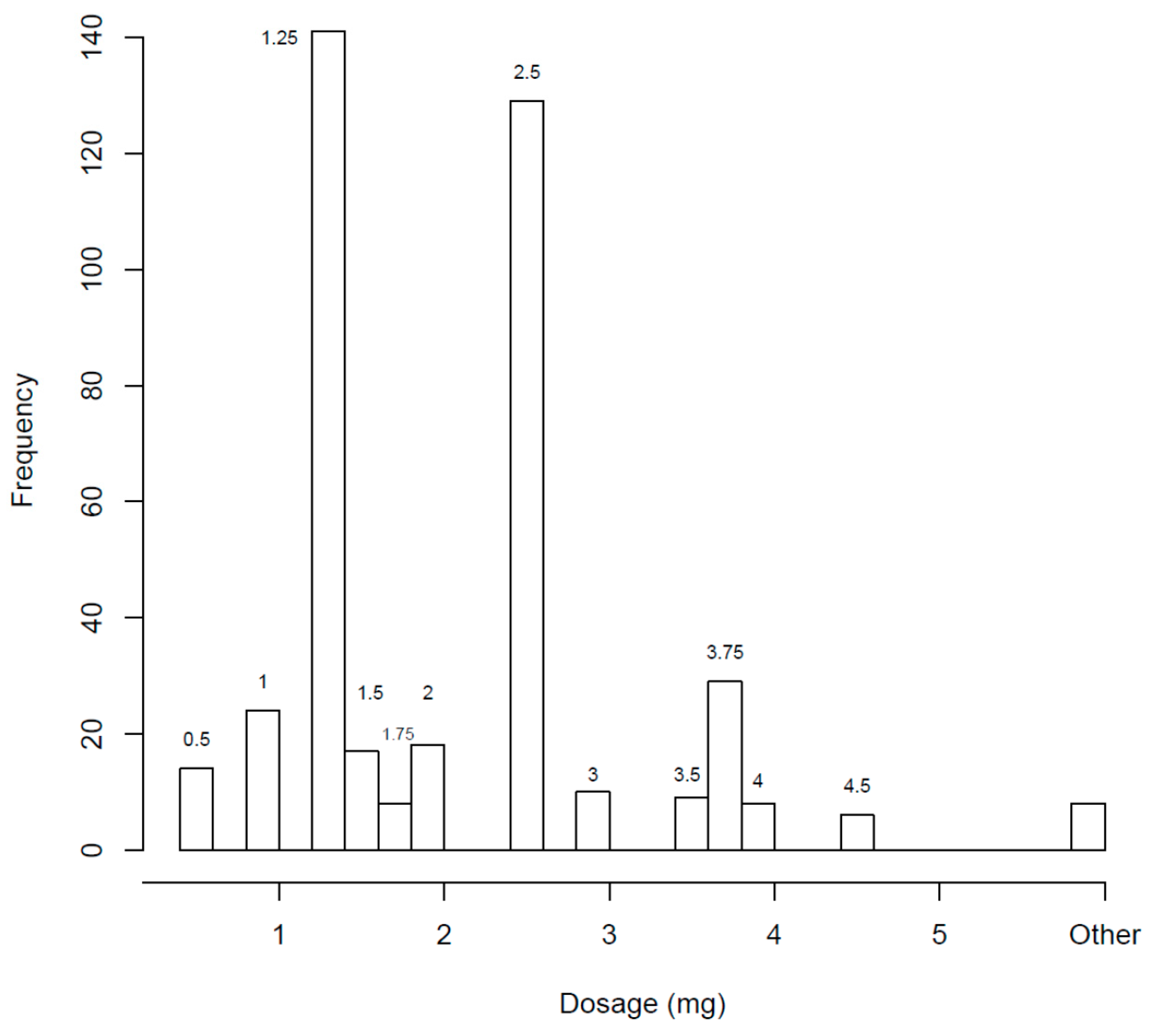

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Speiser, P.W.; Arlt, W.; Auchus, R.J.; Baskin, L.S.; Conway, G.S.; Merke, D.P.; Meyer-Bahlburg, H.F.L.; Miller, W.L.; Murad, M.H.; Oberfield, S.E.; et al. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 4043–4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, E.; Digweed, D.; Quirke, J.; Voet, B.; Ross, R.J.; Davies, M. Hydrocortisone granules are bioequivalent when sprinkled onto food or given directly on the tongue. J. Endocr. Soc. 2019, 3, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merke, D.P.; Cho, D.; Calis, K.A.; Keil, M.F.; Chrousos, G.P. Hydrocortisone suspension and hydrocortisone tablets are not bioequivalent in the treatment of children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Fawcett, J.P.; Boulton, D.W.; Jiang, R.; Woods, D.J. Stability of hydrocortisone oral suspensions prepared from tablets and powder. Ann. Pharmacother. 1995, 29, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.B.; Rogge, M.C.; Selen, A.; Goehl, T.J.; Shah, V.P.; Prasad, V.K.; Welling, P.G. Bioavailability of hydrocortisone from commercial 20-mg tablets. J. Pharm. Sci. 1984, 73, 964–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafoglou, K.; Gonzalez-Bolanos, M.T.; Zimmerman, C.L.; Boonstra, T.; Yaw Addo, O.; Brundage, R. Comparison of cortisol exposures and pharmacodynamic adrenal steroid responses to hydrocortisone suspension vs. Commercial tablets. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 55, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rayess, H.; Addo, O.Y.; Palzer, E.; Jaber, M.; Fleissner, K.; Hodges, J.; Brundage, R.; Miller, B.S.; Sarafoglou, K. Bone age maturation and growth outcomes in young children with cah treated with hydrocortisone suspension. J. Endocr. Soc. 2022, 6, bvab193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, G.; Decarie, D.; Ensom, M.H.H. Stability of hydrocortisone in extemporaneously compounded suspension. J. Inform. Pharmacother. 2003, 13, 100–110. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.V. Formulations: Hydrocortisone 2 mg/mL oral liquid. Int. J. Pharm. Compd. 2004, 8, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, V.D.P. Chemical stabilities of hydrocortisone in an oral liquid dosage form without suspending agents. Int. J. Pharm. Compd. 2007, 11, 259–261. [Google Scholar]

- Santovena, A.; Llabre’s, M.; Farina, J.B. Quality control and physical and chemical stability of hydrocortisone oral suspension: An interlaboratory study. Int. J. Pharm. Compd. 2010, 14, 430–435. [Google Scholar]

- Orlu-Gul, M.; Fisco, G.; Parmar, D.; Gill, H.; Tuleu, C. A new reconstitutable oral paediatric hydrocortisone solution containing hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2013, 39, 1028–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappe, J.; Osman, N.; Cisternino, S.; Fontan, J.E.; Schlatter, J. Stability of hydrocortisone preservative-free oral solutions. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 20, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manchanda, A.; Laracy, M.; Savji, T.; Bogner, R.H. Stability of an alcohol-free, dye-free hydrocortisone (2 mg/mL) compounded oral suspension. Int. J. Pharm. Compd. 2018, 22, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Madathilethu, J.; Roberts, M.; Peak, M.; Blair, J.; Prescott, R.; Ford, J.L. Content uniformity of quartered hydrocortisone tablets in comparison with mini-tablets for paediatric dosing. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2018, 2, e000198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrue, C.; Mehuys, E.; Boussery, K.; Remon, J.P.; Petrovic, M. Tablet-splitting: A common yet not so innocent practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rayess, H.; Fleissner, K.; Jaber, M.; Brundage, R.C.; Sarafoglou, K. Manipulation of hydrocortisone tablets leads to iatrogenic cushing syndrome in a 6-year-old girl with cah. J. Endocr. Soc. 2020, 4, bvaa091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafoglou, K.; Merke, D.P.; Reisch, N.; Claahsen-van der Grinten, H.; Falhammar, H.; Auchus, R.J. Interpretation of steroid biomarkers in 21-hydroxylase deficiency and their use in disease management. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 2154–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, A.C.; Lindemalm, S.; Eksborg, S. Dividing the tablets for children-good or bad? Pharm. Methods 2016, 7, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkees, S.A. Dexamethasone therapy of congenital adrenal hyperplasia and the myth of the “growth toxic” glucocorticoid. Int. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2010, 2010, 569680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punthakee, Z.; Legault, L.; Polychronakos, C. Prednisolone in the treatment of adrenal insufficiency: A re-evaluation of relative potency. J. Pediatr. 2003, 143, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Geras, D.; Hadziomerovic, D.; Leau, A.; Khan, R.N.; Gudka, S.; Locher, C.; Razaghikashani, M.; Lim, L.Y. Accuracy of tablet splitting and liquid measurements: An examination of who, what and how. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2017, 69, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.; Webb, E.A.; Kerr, S.; Davies, J.H.; Stirling, H.; Batchelor, H. How close is the dose? Manipulation of 10mg hydrocortisone tablets to provide appropriate doses to children. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 545, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brustugun, J.; Notaker, N.; Paetz, L.H.; Tho, I.; Bjerknes, K. Adjusting the dose in paediatric care: Dispersing four different aspirin tablets and taking a proportion. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2021, 28, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barillas, J.E.; Eichner, D.; Van Wagoner, R.; Speiser, P.W. Iatrogenic cushing syndrome in a child with congenital adrenal hyperplasia: Erroneous compounding of hydrocortisone. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, E.; Whitaker, M.J.; Keevil, B.; Wales, J.; Ross, R.J. Accuracy of hydrocortisone dose administration via nasogastric tube. Clin. Endocrinol. 2019, 90, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.L.; Stogiannari, M.; Janeczko, S.; Khoshan, M.; Lin, Y.; Isreb, A.; Habashy, R.; Giebultowicz, J.; Peak, M.; Alhnan, M.A. Towards point-of-care manufacturing and analysis of immediate-release 3d printed hydrocortisone tablets for the treatment of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 642, 123072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayyoubi, S.; van Kampen, E.E.M.; Kocabas, L.I.; Parulski, C.; Lechanteur, A.; Evrard, B.; De Jager, K.; Muller, E.; Wilms, E.W.; Meulenhoff, P.W.C.; et al. 3d printed, personalized sustained release cortisol for patients with adrenal insufficiency. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 630, 122466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parulski, C.; Bya, L.A.; Goebel, J.; Servais, A.C.; Lechanteur, A.; Evrard, B. Development of 3d printed mini-waffle shapes containing hydrocortisone for children’s personalized medicine. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 642, 123131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| GC Formulations | Yes * | No |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrocortisone tablets | 184 | 3 |

| Hydrocortisone suspension | 58 | 129 |

| Dexamethasone tablets | 5 | 182 |

| Dexamethasone suspension | 3 | 184 |

| Prednisone tablets | 16 | 171 |

| Prednisone suspension | 12 | 175 |

| Prednisolone tablets | 5 | 182 |

| Prednisolone suspension | 22 | 165 |

| Methods to Achieve Doses of <2.5 mg | Count | Percent * |

|---|---|---|

| Cut by hand | 20 | 10.7 |

| Use a pill-cutter | 163 | 87.2 |

| Use a knife | 23 | 12.3 |

| Dissolve tablets in water | 48 | 25.7 |

| Does not apply to my practice | 4 | 2.14 |

| Don’t know | 3 | 1.6 |

| Other | 9 | 4.81 |

| Reason | Count | Percent * |

|---|---|---|

| Associated with overtreatment | 15 | 11.6 |

| Associated with undertreatment | 21 | 16.3 |

| Hydrocortisone suspension not available | 14 | 10.8 |

| No reliable compounding pharmacy | 50 | 38.7 |

| CAH consensus guidelines | 81 | 62.7 |

| Insurance won’t cover | 10 | 7.7 |

| My training | 87 | 67 |

| Other | 12 | 9.3 |

| Author, Year (Citation) | Suspension Components | Concentration | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fawcett 1995 [4] | Hydrocortisone 20 mg tablets or powder Polysorbate 80 Sodium carboxymethylcellulose syrup BP methyl- and propyl-hydroxybenzoate citric acid monohydrate water | 2.5 mg/mL |

|

| Chong et al., 2003 [8] | 1:1 mixture of Ora-Sweet and Ora-Plus | 1 mg/mL and 2 mg/mL | Physically and chemically stable for up to 91 days at 4 °C and 25 °C |

| Allen 2004 [9] | 100-mg hydrocortisone powder (5 crushed 20 mg tablets) Ora-Plus Plus (suspending agent) 45 mL Ora-Sweet or Ora-Sweet SF (flavoring agent) 100 mL Glycerin 5 mL | 2 mg/mL | No outcomes studied |

| Gupta 2007 [10] | Ethyl alcohol Hydrocortisone Glycerin Ora-Sweet Humco simple syrup Water | 2 mg/mL | Stable for at least 60 days when stored in amber-colored glass bottles at room temperature |

| Santovena 2010 [11] | Hydrocortisone Carboxymethylcellulose Polysorbate-80 Methyl-p-hydroxybenzoate Propyl-p-hydroxybenzoate Sucrose Citric acid Purified water Syrup | 1 mg/mL | Stability confirmed for 90 days at 5 °C |

| Orlu-Gul 2013 [12] | Citric acid buffer (pH 4.2) Hydroxypropyl B-cyclodextrin Orange tangerine (flavoring) Methyl paraben sodium salt/potassium sorbate (preservative) Neotame 0.075% sweetener | 5 mg/mL | Stable for 28 days in refrigerator or at room temperature |

| Chappe 2015 [13] | Hydrocortisone succinate powder in citrate buffers or with sterile water | 1 mg/mL | Stable for 14 days only with refrigeration |

| Manchanda 2018 [14] | 10-mg tablets in a dye-free oral vehicle (Oral Mix, Medisca). | 2 mg/mL | Solubility 230 mcg/mL Stable for 90 days at 4 °C and 25 °C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Rayess, H.; Lahoti, A.; Simpson, L.L.; Palzer, E.; Thornton, P.; Heksch, R.; Kamboj, M.; Stanley, T.; Regelmann, M.O.; Gupta, A.; et al. Practice Variation among Pediatric Endocrinologists in the Dosing of Glucocorticoids in Young Children with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. Children 2023, 10, 1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121871

Al-Rayess H, Lahoti A, Simpson LL, Palzer E, Thornton P, Heksch R, Kamboj M, Stanley T, Regelmann MO, Gupta A, et al. Practice Variation among Pediatric Endocrinologists in the Dosing of Glucocorticoids in Young Children with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. Children. 2023; 10(12):1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121871

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Rayess, Heba, Amit Lahoti, Leslie Long Simpson, Elise Palzer, Paul Thornton, Ryan Heksch, Manmohan Kamboj, Takara Stanley, Molly O. Regelmann, Anshu Gupta, and et al. 2023. "Practice Variation among Pediatric Endocrinologists in the Dosing of Glucocorticoids in Young Children with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia" Children 10, no. 12: 1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121871

APA StyleAl-Rayess, H., Lahoti, A., Simpson, L. L., Palzer, E., Thornton, P., Heksch, R., Kamboj, M., Stanley, T., Regelmann, M. O., Gupta, A., Raman, V., Mehta, S., Geffner, M. E., & Sarafoglou, K., on behalf of the Pediatric Endocrine Society Drug & Therapeutics Committee. (2023). Practice Variation among Pediatric Endocrinologists in the Dosing of Glucocorticoids in Young Children with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. Children, 10(12), 1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121871