Coparenting in English-Speaking and Chinese Families: A Cross-Cultural Comparison Using the Survey Tool CoPAFS

Abstract

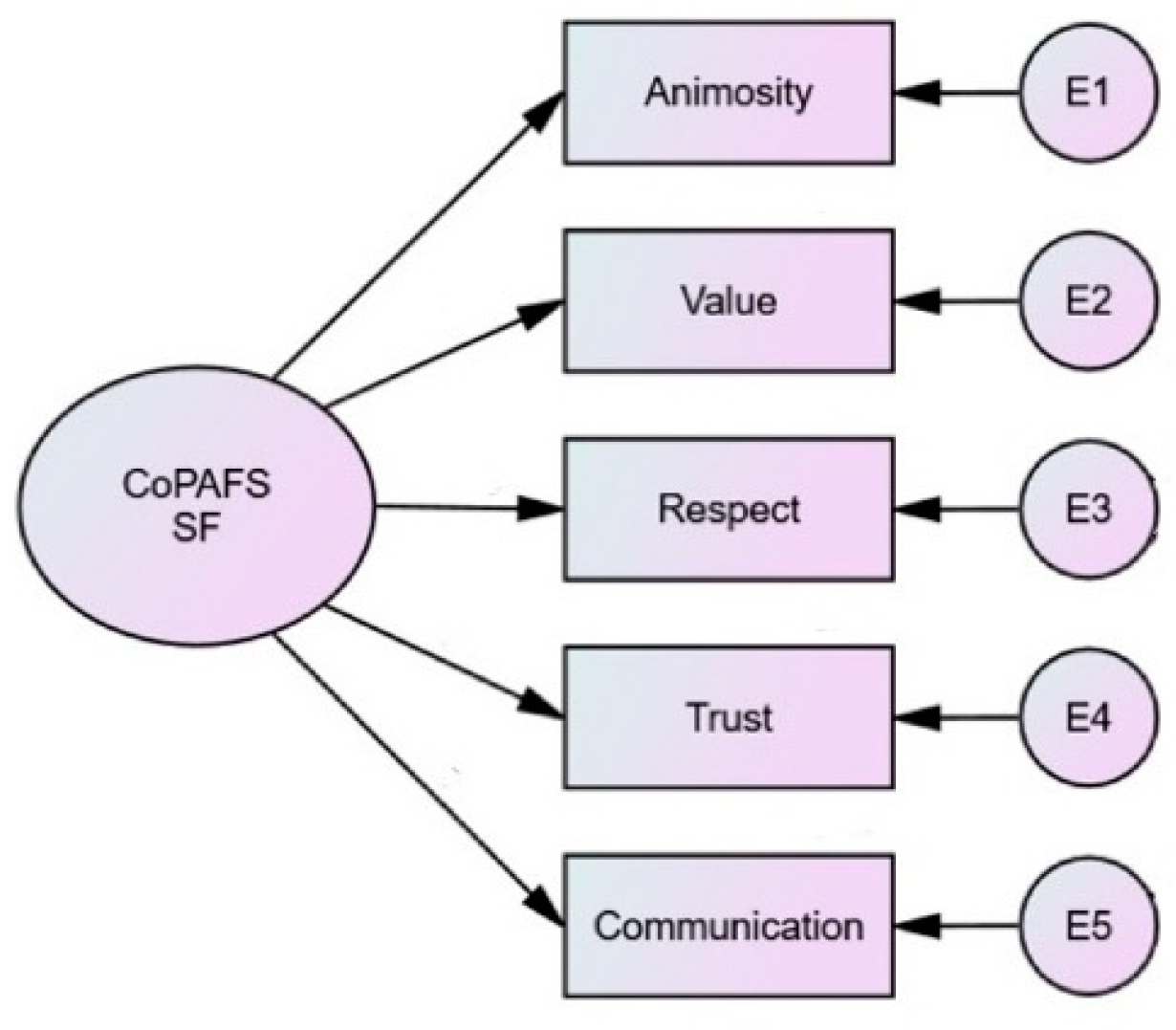

:1. Introduction

1.1. Definition and History of Coparenting Research

1.2. Assessing Coparenting

1.3. Five Factors

1.3.1. Trust

1.3.2. Valuing the Other Parent

1.3.3. Respect

1.3.4. Communication

1.3.5. Animosity

1.3.6. Studying Coparenting beyond the Western Scope

1.3.7. The Present Study and the Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

- Does the measurement model underlying the CoPAFS scale exhibit a good fit with the data gathered from Chinese parents?

- What are the differences in the relative importance of each factor, in terms of each of the factor loadings on coparenting as the latent construct, compared between the English-speaking parents and the Chinese parents?

- Does gender significantly account for the variation on coparenting as well each of the five factors measured by the CoPAFS scale?

- Does culture significantly account for the variation on coparenting as well each of the five factors measured by the CoPAFS scale?

2.1. Participants

| English-Speaking Parents (1) | ||

| Economic Status | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| <USD 20,000 | 3 | 2.0 |

| USD 20,000–39,000 | 2 | 1.3 |

| USD 40,000–59,000 | 6 | 3.9 |

| USD 60,000$−79,000 | 15 | 9.8 |

| USD 80,000 or more | 120 | 78.4 |

| Missing | 7 | 4.6 |

| Total | 153 | 100 |

| Note: Because of slight inconsistency of income standards between the first wave of data and the subsequent two waves, the first sample is listed separately here. | ||

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Data Collection Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis Strategies

3. Results

3.1. Model Fit Examination of CoPAFS Scale Using the Data Collected from Chinese Parents

3.1.1. Cronbach Alpha Values and the Correlation Matrices for Five Factors

3.1.2. Model Fit Indices

3.2. The Relative Importance of Each Factor as Endorsed by English-Speaking Parents and Chinese Parents

3.3. Testing the Significance of Gender and Culture as Two Predictors That Account for the Variation in Coparenting and the Five Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Overview

4.2. Model Fit of CoPAFS under the Chinese Context

4.3. Different Views of Chinese and English-Speaking Parents on Elements of Parenting

4.4. Culture as the More Dominant Predictor than Gender

5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cox, M.J.; Paley, B.; Harter, K. Interparental Conflict and Parent–Child Relationships. In Interparental Conflict and Child Development: Theory, Research and Applications, 1st ed.; Fincham, F.D., Grych, J.H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg, M.E. The Internal Structure and Ecological Context of Coparenting: A Framework for Research and Intervention. Parenting 2002, 3, 95–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egeren, L.A.V.; Hawkins, D.P. Coming to Terms with Coparenting: Implications of Definition and Measurement. J. Adult Dev. 2004, 11, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, J.P. Coparenting and Triadic Interactions during Infancy: The Roles of Marital Distress and Child Gender. Dev. Psychol. 1995, 31, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J.; Crnic, K.; Gable, S. The Determinants of Coparenting in Families with Toddler Boys: Spousal Differences and Daily Hassles. Child Dev. 1995, 66, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolin, G.; Gordis, E.B.; John, R.S. Coparenting: A Link between Marital Conflict and Parenting in Two-Parent Families. J. Fam. Psychol. 2001, 15, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riina, E.M.; Feinberg, M.E. The Trajectory of Coparenting Relationship Quality across Early Adolescence: Family, Community, and Parent Gender Influences. J. Fam. Psychol. 2018, 32, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Cheng, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, R.; Zhu, D. Literature review on coparenting and related scales or questionnaires commonly used. Chin. J. Child Health Care 2021, 29, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.J.; Paley, B. Families as Systems. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1997, 48, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stright, A.D.; Bales, S.S. Coparenting Quality: Contributions of Child and Parent Characteristics. Fam. Relat. 2003, 52, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, S.; Chen, B. A Study on the “Red Face and White Face” under the Three-Dimensional Construct of Coparenting in Chinese Families. J. Soochow Univ. Educ. Sci. Ed. 2018, 6, 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Lin, X. From “Strict Father, Kind Mother” to “Strict Mother, Kind Father”: The Differences in Strictness towards Educating Children and an Analysis of the Causes. Educ. Res. Mon. 2018, 35, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.B.; Zou, S.Q.; Wu, X.C.; Liu, C. The Association between Father Coparenting Behavior and Adolescents’ Peer Attachment: The Mediating Role of Father-Child Attachment and the Moderating Role of Adolescents’ Neuroticism. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2019, 35, 176–183. [Google Scholar]

- McHale, J.P. Overt and Covert Coparenting Processes in the Family. Fam. Process 1997, 36, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, J.; Fivaz-Depeursinge, E.; Dickstein, S.; Robertson, J.; Daley, M. New Evidence for the Social Embeddedness of Infants’ Early Triangular Capacities. Fam. Process 2008, 47, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinberg, M.E.; Kan, M.L. Establishing Family Foundations: Intervention Effects on Coparenting, Parent/Infant Well-Being, and Parent–Child Relations. J. Fam. Psychol. 2008, 22, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, M.; Jones, D.; Kan, M.; Goslin, M. Effects of Family Foundations on Parents and Children: 3.5 Years After Baseline. J. Fam. Psychol. 2010, 24, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinberg, M.E.; Brown, L.D.; Kan, M.L. A Multi-Domain Self-Report Measure of Coparenting. Parenting 2012, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reader, J.M.; Teti, D.M.; Cleveland, M.J. Cognitions about Infant Sleep: Interparental Differences, Trajectories across the First Year, and Coparenting Quality. J. Fam. Psychol. 2017, 31, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Ye, P.; Bian, Y. Psychometric Properties of the Coparenting Relationship Scale in Chinese Parents. Fam. Relat. 2022, 72, 1694–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teubert, D.; Pinquart, M. The Coparenting Inventory for Parents and Adolescents (CI-PA). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2011, 27, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, G.; Antonietti, J.-P.; Sznitman, G.A.; Petegem, S.V.; Darwiche, J. The French Version of the Coparenting Inventory for Parents and Adolescents (CI-PA): Psychometric Properties and a Cluster Analytic Approach. J. Fam. Stud. 2022, 28, 652–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallette, J.K.; Futris, T.G.; Brown, G.L.; Oshri, A. Cooperative, Compromising, Conflictual, and Uninvolved Coparenting among Teenaged Parents. J. Fam. Issues 2019, 40, 1534–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni, A.; Donato, S.; Molgora, S. When “We” Are Stressed: A Dyadic Approach to Coping with Stressful Events, 1st ed.; Nova Science Pub Inc: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–228. [Google Scholar]

- Righetti, F.; Finkenauer, C. If You Are Able to Control Yourself, I Will Trust You: The Role of Perceived Self-Control in Interpersonal Trust. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 874–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L. Trust and Breach of the Psychological Contract. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 574–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, H.; Shaver, P. Intimacy as an Interpersonal Process. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 74, 1238–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M. Attachment Working Models and the Sense of Trust: An Exploration of Interaction Goals and Affect Regulation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1209–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, J.A. Adult romantic attachment and couple relationships. In Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications, 3rd ed.; Cassidy, J., Shaver, P.R., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 355–377. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Florian, V.; Cowan, P.A.; Cowan, C.P. Attachment security in couple relationships: A systemic model and its implications for family dynamics. Fam. Process 2002, 41, 405–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheftall, A.H.; Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J.; Futris, T.G. Adolescent Mothers’ Perceptions of the Coparenting Relationship with Their Child’s Father: A Function of Attachment Security and Trust. J. Fam. Issues 2010, 31, 884–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, J.; Lafontaine, M.-F. Attachment, Trust, and Satisfaction in Relationships: Investigating Actor, Partner, and Mediating Effects. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 24, 640–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, E.J.; Burnette, J.L.; Scissors, L.E. Vengefully Ever after: Destiny Beliefs, State Attachment Anxiety, and Forgiveness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, K. Partnership Parenting: How Men and Women Parent Differently-Why It Helps Your Kids and Can Strengthen Your Marriage, 1st ed.; Da Capo Lifelong Books: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–240. [Google Scholar]

- Giannotti, M.; Mazzoni, N.; Bentenuto, A.; Venuti, P.; de Falco, S. Family Adjustment to COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy: Parental Stress, Coparenting, and Child Externalizing Behavior. Fam. Process 2022, 61, 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, F. Strengthening Family Resilience, 3rd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–400. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, R.S.; Weissman, S.H. Parenthood: A Psychodynamic Perspective, 1st ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 1–426. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, J.; Liang, L.; Bian, Y. The Coparenting Relationship in Chinese Families: The Role of Parental Neuroticism and Depressive Symptoms. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2021, 38, 2587–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.M.; Esses, V.M.; Burris, C.T. Contemporary Sexism and Discrimination: The Importance of Respect for Men and Women. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrick, S.S.; Hendrick, C. Measuring Respect in Close Relationships. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2006, 23, 881–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, H.; Stanley, S.; Blumberg, S.L. Fighting for Your Marriage: Positive Steps for Preventing Divorce and Preserving a Lasting Love, 1st ed.; Jossey Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 1–374. [Google Scholar]

- Frei, J.R.; Shaver, P.R. Respect in Close Relationships: Prototype Definition, Self-Report Assessment, and Initial Correlates. Pers. Relatsh. 2002, 9, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.; Quirk, K.; Manthos, M. I Get No Respect: The Relationship Between Betrayal Trauma and Romantic Relationship Functioning. J. Trauma Dissociation 2012, 13, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowen, L.K.; Catania, J.A.; Dolcini, M.M.; Harper, G.W. The Meaning of Respect in Romantic Relationships Among Low-Income African American Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Res. 2014, 29, 639–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iafrate, R.; Bertoni, A.; Donato, S.; Finkenauer, C. Perceived Similarity and Understanding in Dyadic Coping among Young and Mature Couples. Pers. Relatsh. 2012, 19, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdandžić, M.; Vente, W.; Feinberg, M.; Aktar, E.; Bögels, S. Bidirectional Associations Between Coparenting Relations and Family Member Anxiety: A Review and Conceptual Model. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 15, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gable, S.L.; Gonzaga, G.C.; Strachman, A. Will You Be There for Me When Things Go Right? Supportive Responses to Positive Event Disclosures. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F. Normal Family Processes: Growing Diversity and Complexity, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–592. [Google Scholar]

- Socha, T.J.; Stamp, G.H. Parents, Children, and Communication: Frontiers of Theory and Research, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 1–400. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona, C.E.; Shaffer, P.A.; Wesner, K.A.; Gardner, K.A. Optimally Matching Support and Perceived Spousal Sensitivity. J. Fam. Psychol. 2007, 21, 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottman, J.; Gottman, J.M.; Silver, N. Why Marriages Succeed or Fail: And How You Can Make Yours Last, 1st ed.; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 1–242. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, B.M.; Moloney, L.J. Entrenched Postseparation Parenting Disputes: The Role of Interparental Hatred? Fam. Court Rev. 2017, 55, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borievi, V. Coparenting within the Family System: Review of Literature. Coll. Antropol. 2013, 37, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.T. Parental Depression and Cooperative Coparenting: A Longitudinal and Dyadic Approach. Fam. Relat. 2018, 67, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, B.; Bullock, A.; Liu, J.; Coplan, R.J. The Longitudinal Links between Marital Conflict and Chinese Children’s Internalizing Problems in Mainland China: Mediating Role of Maternal Parenting Styles. Fam. Process 2021, 61, 1749–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.J.; Gamble, W.C. Pathways of Influence: Marital Relationships and Their Association with Parenting Styles and Sibling Relationship Quality. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2008, 17, 757–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Lansford, J.E.; Schwartz, D.; Farver, J.M. Marital Quality, Maternal Depressed Affect, Harsh Parenting, and Child Externalising in Hong Kong Chinese Families. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2004, 28, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. The Future of Coparenting. China Fam. Educ. 2022, 31, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Chen, M.; He, R.; Xu, T. Toward an Integrative Framework of Intergenerational Coparenting within Family Systems: A Scoping Review. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2023, 15, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L. Research on the Coparenting of Children by Grandparents and Parents in Three-Generational Families. Master’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2017. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.X. Interaction between Grandparent-Parent Co-Parenting Relationship and Young Children’s Temperament. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 29, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cheng, N. Co-Parenting and the Influence on Child Adjustment. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.; Cheung, P.C. Relations between Chinese Adolescents’ Perception of Parental Control and Organization and Their Perception of Parental Warmth. Dev. Psychol. 1987, 23, 726–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.-M.; Luster, T. Factors Related to Parenting Practices in Taiwan. Early Child Dev. Care 2002, 172, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Farver, J.A.M.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Yu, L.; Cai, B. Mainland Chinese Parenting Styles and Parent–Child Interaction. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2005, 29, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, R.K. Cultural explanations for the role of parenting in the school success of Asian-American children. In Resilience across Contexts: Family, Work, Culture, and Community, 1st ed.; Taylor, R.D., Wang, M.C., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 333–363. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind, D.; Black, A.E. Socialization Practices Associated with Dimensions of Competence in Preschool Boys and Girls. Child Dev. 1967, 38, 291–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Sun, P.; Yu, Z. A Comparative Study on Parenting of Preschool Children Between the Chinese in China and Chinese Immigrants in the United States. J. Fam. Issues 2017, 38, 1262–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Cuskelly, M.; Gilmore, L.; Sullivan, K. Authoritative Parenting of Chinese Mothers of Children with and without Intellectual Disability. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Cheah, C.S.L.; Hart, C.H.; Sun, S.; Olsen, J.A. Confirming the Multidimensionality of Psychologically Controlling Parenting among Chinese-American Mothers: Love Withdrawal, Guilt Induction, and Shaming. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2015, 39, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, M.; Pruett, M.K.; Alschech, J.; Sushchyk, A.R. A Pilot Study to Assess Coparenting Across Family Structures (CoPAFS). J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 1392–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–534. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, A.W.; Johnson, E.C.; Braddy, P.W. Power and Sensitivity of Alternative Fit Indices in Tests of Measurement Invariance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 568–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsey, E.W.; Caldera, Y.M. Mother–Father–Child Triadic Interaction and Mother–Child Dyadic Interaction: Gender Differences within and between Contexts. Sex Roles 2006, 55, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, P.; Folbre, N. Involving dads: Parental bargaining and family well-being. In Handbook of Father Involvement, 2nd ed.; Cabrera, N.J., Tamis-Lamonda, C.S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 1–504. [Google Scholar]

- Kwok, S.Y.C.L.; Cheng, L.; Chow, B.W.Y.; Ling, C.C.Y. The Spillover Effect of Parenting on Marital Satisfaction Among Chinese Mothers. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, X. Dyadic Effects of Marital Satisfaction on Coparenting in Chinese Families: Based on the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. Int. J. Psychol. 2018, 53, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Lotz, A.; Alyousefi-van Dijk, K.; van IJzendoorn, M. Birth of a Father: Fathering in the First 1000 Days. Child Dev. Perspect. 2019, 13, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, R.W.H.; Kwok, S.Y.C.L.; Ling, C.C.Y. The Moderating Roles of Parenting Self-Efficacy and Co-Parenting Alliance on Marital Satisfaction among Chinese Fathers and Mothers. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 3506–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q. Trend, Source and Heterogeneity of the Change of Gender-Role Attitude in China: A Case Study of Two Indicators. J. Chin. Women’s Stud. 2016, 25, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, X.; Loke, A.Y. Experiences of Intergenerational Co-Parenting during the Postpartum Period in Modern China: A Qualitative Exploratory Study. Nurs. Inq. 2021, 28, e12403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y. Thoughts on the marriage outlook of the post-80s generation. Leg. Syst. Soc. 2012, 25, 175–176. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Sun, R.C.F. Parenting in Hong Kong: Traditional Chinese Cultural Roots and Contemporary Phenomena. In Parenting Across Cultures: Childrearing, Motherhood and Fatherhood in Non-Western Cultures; Selin, H., Ed.; Science Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Science; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L. Observation and educational thinking on the problem of the only child in the city. China Electr. Power Educ. 2009, 16, 5–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Cote, L.R.; Haynes, O.M.; Suwalsky, J.T.D.; Bakeman, R. Modalities of Infant–Mother Interaction in Japanese, Japanese American Immigrant, and European American Dyads. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 2073–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, M.H. Parenting science and practice. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Child Psychology in Practice, 4th ed.; Renninger, K.A., Sigel, I.E., Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 893–949. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, M.H. On the significance of social relationships in the development of children’s earliest symbolic play: An ecological perspective. In Play and Development, 1st ed.; Goncu, A., Gaskins, S., Eds.; Psychology Press: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 101–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama, S.; Cohen, D. Handbook of Cultural Psychology, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 1–930. [Google Scholar]

- van de Vijver, F.; Leung, K. Methods and Data Analysis for Cross-Cultural Research, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 1–200. [Google Scholar]

- Lantz, B. The Large Sample Size Fallacy. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2013, 27, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Chinese Parents | English-Speaking Parents (1) | English-Speaking Parents (2) | English-Speaking Parents (3) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Frequency | Percent (%) | Frequency | Percent (%) | Significant (Y/N) | Frequency | Percent (%) | Significant (Y/N) | Frequency | Percent (%) | Significant (Y/N) |

| Under 20 | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | N p = 0.84 | 0 | 0 | N p = 0.84 | 0 | 0 | N p = 0.84 |

| 20–29 | 34 | 6.4 | 13 | 8.5 | N p = 0.19 | 12 | 9.5 | N p = 0.19 | 9 | 8.4 | N p = 0.24 |

| 30–39 | 238 | 44.6 | 64 | 41.8 | N p = 0.73 | 75 | 59.5 | Y p = 0.03 | 48 | 44.9 | N p = 0.48 |

| 40–49 | 240 | 44.9 | 54 | 35.3 | N p = 0.98 | 27 | 21.4 | N p = 1.00 | 43 | 40.2 | N p = 0.82 |

| 50 and older | 20 | 3.7 | 20 | 13.1 | Y p < 0.01 | 12 | 9.5 | Y p = 0.02 | 7 | 6.5 | N p = 0.13 |

| Missing | 1 | .2 | 2 | 1.3 | 13 | 9.4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Total | 533 | 100.0 | 153 | 100 | 139 | 100.0 | 107 | 100.0 | |||

| Chinese Parents | English-Speaking Parents (1) | English-Speaking Parents (2) | English-Speaking Parents (3) | ||||||||

| Education Level | Frequency | Percent (%) | Frequency | Percent (%) | Significant (Y/N) | Frequency | Percent (%) | Significant (Y/N) | Frequency | Percent (%) | Significant (Y/N) |

| Lower than high school | 7 | 1.3 | 3 | 2.0 | N p = 0.29 | 3 | 2.2 | N p = 0.26 | N/A | N/A | |

| High school/Post-Secondary | 38 | 7.1 | 8 | 5.2 | N p = 0.81 | 9 | 6.5 | N p = 0.60 | N/A | N/A | |

| Specialist | 49 | 9.2 | 30 | 19.6 | Y p < 0.01 | 9 | 6.5 | N p = 0.86 | N/A | N/A | |

| University | 324 | 60.7 | 103 | 67.3 | N p = 0.17 | 99 | 71.2 | Y p < 0.01 | N/A | N/A | |

| Others | 113 | 21.2 | 0 | 0 | N p = 1.00 | 0 | 0 | N p = 1.00 | N/A | N/A | |

| Missing | 3 | 0.6 | 9 | 5.9 | 19 | 13.7 | N/A | N/A | |||

| Total | 534 | 100.0 | 153 | 100 | 139 | 100 | N/A | N/A | |||

| Chinese Parents | English-Speaking Parents (2) | English-Speaking Parents (3) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Status | Frequency | Percent (%) | Frequency | Percent (%) | Significant (Y/N) | Frequency | Percent (%) | Significant (Y/N) |

| Poor | 19 | 21.2 | 9 | 6.5 | N p = 0.09 | 6 | 5.6 | N p = 0.09 |

| Working class | 272 | 1.3 | 15 | 10.8 | N p = 1.00 | 22 | 20.6 | N p = 1.00 |

| Lower middle class | 86 | 7.1 | 12 | 8.6 | N p = 0.99 | 26 | 24.3 | Y p = 0.03 |

| Upper middle class | 149 | 60.7 | 30 | 21.6 | N p = 0.94 | 22 | 20.6 | N p = 0.95 |

| Upper class | 5 | 9.2 | 20 | 14.4 | Y p < 0.01 | 31 | 29.0 | Y p < 0.01 |

| Missing | 3 | 0.6 | 53 | 38.1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 534 | 100.0 | 139 | 100 | 107 | 100 | ||

| V |

| R |

| A * |

| C |

| A * |

| C |

| A * |

| V * |

| C |

| A * |

| T * |

| C |

| V * |

| R |

| T * |

| V |

| A * |

| T * |

| C |

| T * |

| T |

| R * |

| R |

| T * |

| A * |

| V |

| T * |

| Cronbach Alpha | Number of Items per Factor | |

|---|---|---|

| Value | 0.50 | 5 |

| Trust | 0.86 | 7 |

| Respect | 0.30 | 4 |

| Animosity | 0.88 | 6 |

| Communication | 0.84 | 5 |

| Value | Trust | Respect | Animosity | Communication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 1 | ||||

| Trust | 0.704 ** | 1 | |||

| Respect | 0.743 ** | 0.522 ** | 1 | ||

| Animosity | 0.748 ** | 0.866 ** | 0.553 ** | 1 | |

| Communication | 0.354 ** | 0.081 | 0.513 ** | −0.013 | 1 |

| Animosity | Value | Respect | Trust | Communication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese Married Mothers | 0.98 *** (96.7%) | 0.75 *** (57.2%) | 0.57 *** (32.7%) | 0.86 *** (74.4%) | 0.00 (0.0%) |

| Chinese Married Fathers | 0.97 *** (94.5%) | 0.72 *** (53.1%) | 0.52 *** (27.1%) | 0.90 *** (82.1%) | −0.03 (0.0%) |

| English-speaking Married Mothers | 0.87 *** (77.2%) | 0.71 *** (50.6%) | 0.89 *** (80.3%) | 0.89 *** (80.3%) | 0.86 *** (74.7%) |

| English-speaking Married Fathers | 0.82 *** (76.2%) | 0.81 *** (66.5%) | 0.87 *** (76.9%) | 0.97 *** (87.0%) | 0.83 *** (70.4%) |

| Model | Chi-Square (p Value) | DF | CFI | RMSEA | ΔChi-Square | Δdf | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1-configural | 19.86 | 4 | 0.99 | 0.05 | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P |

| M2-metric | 20.27 | 9 | 0.99 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 5 | 0 | 0.01 | Accept (p = 0.66) |

| M3-scalar | 30.86 | 17 | 0.99 | 0.03 | 10.59 | 8 | 0 | 0.01 | Accept (p = 0.22) |

| Model | Chi-Square (p Value) | DF | CFI | RMSEA | ΔChi-Square | Δdf | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1-configural | 132.81 | 14 | 0.93 | 0.14 | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P |

| M2-metric | 132.82 | 15 | 0.93 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Accept (p = 0.38) |

| M3-scalar | 146.17 | 20 | 0.92 | 0.12 | 13.35 | 6 | −0.01 | −0.02 | Accept (p = 0.02) |

| Model | Chi-Square (p VALUE) | DF | CFI | RMSEA | ΔChi-Square | Δdf | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1-configural | 43.86 | 4 | 0.84 | 0.27 | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P |

| M2-metric | 479.95 | 9 | 0.84 | 0.25 | 436.09 | 5 | 0 | 0.02 | Reject (p < 0.01) |

| M3-scalar | 735.28 | 17 | 0.76 | 0.23 | 255.33 | 8 | 0.08 | 0.02 | Reject (p < 0.01) |

| Model | Chi-Square (p Value) | DF | CFI | RMSEA | ΔChi-Square | Δdf | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1-configural | 12.73 | 4 | 0.87 | 0.25 | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P |

| M2-metric | 81.41 | 9 | 0.87 | 0.23 | 68.68 | 5 | 0 | 0.02 | Accept (p = 0.47) |

| M3-scalar | 166.34 | 17 | 0.73 | 0.24 | 84.93 | 8 | 0.01 | 0.01 | Reject (p < 0.01) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, T.; Pruett, M.K.; Alschech, J. Coparenting in English-Speaking and Chinese Families: A Cross-Cultural Comparison Using the Survey Tool CoPAFS. Children 2023, 10, 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121884

Zhu T, Pruett MK, Alschech J. Coparenting in English-Speaking and Chinese Families: A Cross-Cultural Comparison Using the Survey Tool CoPAFS. Children. 2023; 10(12):1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121884

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Tianmei, Marsha Kline Pruett, and Jonathan Alschech. 2023. "Coparenting in English-Speaking and Chinese Families: A Cross-Cultural Comparison Using the Survey Tool CoPAFS" Children 10, no. 12: 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121884

APA StyleZhu, T., Pruett, M. K., & Alschech, J. (2023). Coparenting in English-Speaking and Chinese Families: A Cross-Cultural Comparison Using the Survey Tool CoPAFS. Children, 10(12), 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121884