The Role of a First Aid Training Program for Young Children: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What is the content of the first aid interventions at primary school?

- What are the standard practices and assessments of first aid interventions?

- What is the current evidence for the effectiveness of interventions?

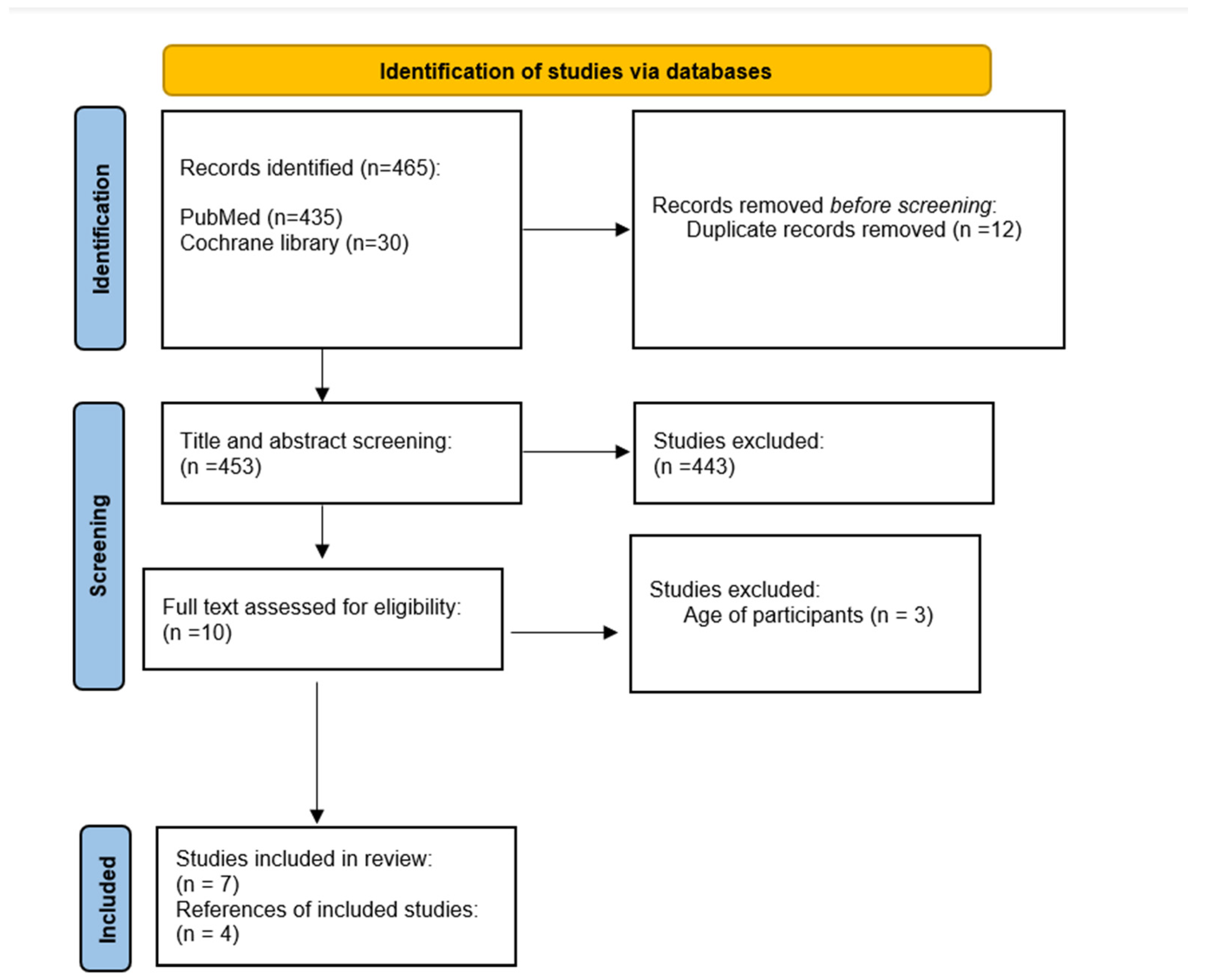

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Search Eligibility

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Study Quality Assessment

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Search Terms/Limits | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (First aid).m_titl. | 37,000 |

| 2 | (Primary school children).m_titl. | 139,309 |

| 3 | 1 and 2 | 532 |

| 4 | limit 3 to english language | 506 |

| 5 | limit 4 to yr = “1990–2021” | 435 |

| No. | Search Terms/Limits | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (First aid).m_titl. | 513 |

| 2 | (Primary school children).m_titl. | 108 |

| 3 | 1 and 2 | 31 |

| 4 | limit 3 to english language | 31 |

| 5 | limit 4 to yr = “1990–2021” | 30 |

References

- Kuvaki, B.; Özbilgin, Ş. School Children Save Lives. Turk. J. Anaesthesiol. Reanim. 2018, 46, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semeraro, F.; Wingen, S.; Schroeder, D.C.; Ecker, H.; Scapigliati, A.; Ristagno, G.; Cimpoesu, D.; Böttiger, B.W. KIDS SAVE LIVES-Three years of implementation in Europe. Resuscitation 2018, 131, e9–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bollig, G.; Wahl, H.A.; Svendsen, M.V. Primary school children are able to perform basic life-saving first aid measures. Resuscitation 2009, 80, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubrano, R.; Romero, S.; Scoppi, P.; Cocchi, G.; Baroncini, S.; Elli, M.; Turbacci, M.; Scateni, S.; Travasso, E.; Benedetti, R.; et al. How to become an under 11 rescuer: A practical method to teach first aid to primary schoolchildren. Resuscitation 2005, 64, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uray, T.; Lunzer, A.; Ochsenhofer, A.; Thanikkel, L.; Zingerle, R.; Lillie, P.; Brandl, E.; Sterz, F. Feasibility of life-supporting first-aid (LSFA) training as a mandatory subject in primary schools. Resuscitation 2003, 59, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfai, B.; Pek, E.; Pandur, A.; Csonka, H.; Betlehem, J. ‘The year of first aid’: Effectiveness of a 3-day first aid programme for 7–14-year-old primary school children. Emerg. Med. J. 2017, 34, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fleischhackl, R.; Nuernberger, A.; Sterz, F.; Schoenberg, C.; Urso, T.; Habart, T.; Mittlboeck, M.; Chandra-Strobos, N. School children sufficiently apply life supporting first aid: A prospective investigation. Crit. Care 2009, 13, R127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frederick, K.; Bixby, E.; Orzel, M.N.; Stewart-Brown, S.; Willett, K. An evaluation of the effectiveness of the Injury Minimization Programme for Schools (IMPS). Inj. Prev. 2000, 6, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, I.; Whitfield, R.; Colquhoun, M.; Chamberlain, D.; Vetter, N.; Newcombe, R. At what age can schoolchildren provide effective chest compressions? An observational study from the Heartstart UK schools training programme. BMJ 2007, 334, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Connolly, M.; Toner, P.; Connolly, D.; McCluskey, D.R. The ‘ABC for life’ programme—Teaching basic life support in schools. Resuscitation 2007, 72, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K.; Mohan, C.; Stevenson, M.; McCluskey, D. Objective assessment of cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills of 10–11-year-old schoolchildren using two different external chest compression to ventilation ratios. Resuscitation 2009, 80, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toner, P.; Connolly, M.; Laverty, L.; McGrath, P.; Connolly, D.; McCluskey, D.R. Teaching basic life support to school children using medical students and teachers in a ‘peer-training’ model—Results of the ‘ABC for life’ programme. Resuscitation 2007, 75, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthelot, S.; Plourde, M.; Bertrand, I.; Bourassa, A.; Couture, M.-M.; Berger-Pelletier, É.; St-Onge, M.; Leroux, R.; Le Sage, N.; Camden, S. Push hard, push fast: Quasi-experimental study on the capacity of elementary schoolchildren to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Scand J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2013, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tools; NHLBI: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Reveruzzi, B.; Buckley, L.; Sheehan, M. School-Based First Aid Training Programs: A Systematic Review. J. Sch. Health 2016, 86, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, E.; Khalemsky, A.; Khalemsky, M. Game-related injuries in schools: A retrospective nationwide 6-year evaluation and implications for prevention policy. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2021, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Wynn, P.; Kendrick, D. Non-resuscitative first-aid training for children and laypeople: A systematic review. Emerg. Med. J. 2014, 31, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tse, E.; Plakitsi, K.; Voulgaris, S.; Alexiou, G.A. First Aid Training for Children in Kindergarten: A Pilot Randomized Control Study. Children 2022, 9, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, E.; Plakitsi, K.; Voulgaris, S.; Alexiou, G.A. Teaching Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Defibrillation in Children. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2022, 38, e1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tse, E.; Alexiou, G. First Aid Training to School Students: Should Younger Children Be Trained? Indian Pediatr. 2021, 58, 1099–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajervatan, A.; Raeisi, A.R.; Atighechian, G.; Tavakoli, N.; Muosavi, H. The Efficacy of Operational First Aid Training Course in Preschool Children. Health Emerg. Disasters Q 2020, 6, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katona, Z.; Tarkó, K.; Berki, T. First Aid Willingness Questionnaire for Schoolchildren: An Exploratory Factor Analysis and Correlation Study. Children 2022, 9, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reder, S.; Cummings, P.; Quan, L. Comparison of three instructional methods for teaching cardiopulmonary resuscitation and use of an automatic external defibrillator to high school students. Resuscitation 2006, 69, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minna, S.; Leena, H.; Tommi, K. How to evaluate first aid skills after training: A systematic review. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2022, 30, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böttiger, B.W.; Semeraro, F.; Altemeyer, K.H.; Breckwoldt, J.; Kreimeier, U.; Rücker, G.; Andres, J.; Lockey, A.; Lippert, F.K.; Georgiou, M.; et al. KIDS SAVE LIVES: School children education in resuscitation for Europe and the world. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2017, 34, 792–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S. Supporting mandatory first aid training in primary schools. Nurs. Stand. 2012, 27, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, A.; Van Aken, H.; Lukas, R.P.; Weber, T.; Breckwoldt, J. Schoolchildren as lifesavers in Europe–Training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation for children. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2013, 27, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, J.; Pendergast, D. Skills for life: First aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation in schools. Health Educ. J. 2017, 76, 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, E.; Alexiou, G. Letter to the Editor: Non-Resuscitative First Aid Training and Assessment for Junior Secondary School Students. Medicine Correspondence Blog. 2021. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/md-journal/Blog/MedicineCorrespondenceBlog/pages/post.aspx?PostID=161 (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Louis, C.J.; Beaumont, C.; Velilla, N.; Greif, R.; Fernandez, J.; Reyero, D. The “ABC SAVES LIVES”: A Schoolteacher-Led Basic Life Support Program in Navarra, Spain. SAGE Open 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metelmann, C.; Metelmann, B.; Schuffert, L.; Hahnenkamp, K.; Vollmer, M.; Brinkrolf, P. Smartphone apps to support laypersons in bystander CPR are of ambivalent benefit: A controlled trial using medical simulation. Scand J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2021, 29, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, L.; Sheehan, M.; Dingli, K.; Reveruzzi, B.; Horgan, V. Taking care of friends: The implementation evaluation of a peer-focused school program using first aid to reduce adolescent risk-taking and injury. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahal, G.; Vaidya, P. Knowledge of first aid in school students and teachers. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2022, 20, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Movahed, M.; Khaleghi-Nekou, M.; Alvani, E.; Sharif-Alhoseini, M. The Impact of Psychological First aid Training on the Providers: A Systematic Review. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 17, e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huy, L.D.; Tung, P.T.; Nhu, L.N.Q.; Linh, N.T.; Tra, D.T.; Thao, N.V.P.; Tien, T.X.; Hai, H.H.; Van Khoa, V.; Phuong, N.T.A.; et al. The willingness to perform first aid among high school students and associated factors in Hue, Vietnam. PloS ONE 2022, 17, e0271567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Yeung, C.Y.; Sharma, A.; So, K.Y.; Ko, H.F.; Wong, K.; Lam, P.; Lee, A. Non-resuscitative first aid training and assessment for junior secondary school students: A pre-post study. Medicine 2021, 100, e27051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plischewski, H.; Kucirkova, N.; Anda Haug, I.; Tanum, I.; Lea, S. Children save lives: Evaluation of a first aid training in Norwegian kindergartens. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2021, 29, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Buck, E.; Laermans, J.; Vanhove, A.-C.; Dockx, K.; Vandekerckhove, P.; Geduld, H. An educational pathway and teaching materials for first aid training of children in sub-Saharan Africa based on the best available evidence. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bánfai, B.; Pandur, A.; Schiszler, B.; Pék, E.; Radnai, B.; Bánfai-Csonka, H.; Betlehem, J. Little lifesavers: Can we start first aid education in kindergarten?—A longitudinal cohort study. Health Educ. J. 2018, 77, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Study Design | Number of Participants | Age | Continent | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bollig et al., 2009 [3] | Experimental study | 228 | 6–7 | Europe | Good |

| Lubrano et al., 2005 [4] | Experimental study | 469 | 8–11 | Europe | Good |

| Uray et al., 2003 [5] | Observational study | 47 | 6–7 | Europe | Good |

| Banfai et al., 2017 [6] | Observational study | 582 | 7–14 | Europe | Good |

| Fleischhackl et al., 2009 [7] | Observational study | 151 | 9–18 | Europe | Good |

| Frederick et al., 2000 [8] | Experimental study | 1200 | 10–11 | Europe | Good |

| Jones et al., 2007 [9] | Observational study | 157 | 9–14 | America | Good |

| Connolly et al., 2007 [10] | Experimental study | 79 | 10–12 | Europe | Good |

| Hill et al., 2009 [11] | Experimental study | 85 | 10–11 | Europe | Good |

| Toner et al., 2007 [12] | Observational study | 190 | 10–12 | Europe | Good |

| Berthelot et al., 2013 [13] | Experimental study | 80 | 10–12 | America | Good |

| Author, Year | Instructor | Lessons | Duration per Session (min) | Content of Program | Evaluation Tool | Educational Material |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bollig et al., 2009 [3] | First Aid Professional | 5 | 45 | B, F, C, B, WT, BL, U, OA, RP, BIES, EC | Test scenario | Glove puppet |

| Lubrano et al., 2005 [4] | First Aid Professional | 3 | 45 | BT, NB, PBLS | Multiple- choice & semi- structured test | slide projector & two pediatric simulators |

| Uray et al., 2003 [5] | First Aid Professional & teachers | 5 | 120 | EC, CPR, AED, RP, BL, BU | Questionnaire s & videotapes of the training | Game & manikins |

| Banfai et al., 2017 [6] | First Aid Professional | 3 | 45 | BLS, AED, U, BL, EC | questionnaire & observation | Scenario |

| Fleischhackl et al., 2009 [7] | Teachers | Not Provided | 360 | EC, CFVS, RP, CPR AED | Practice in Manikin | Manikins |

| Frederick et al., 2000 [8] | Teachers & first aid professionals | Not Provided | Not Provided | BLS, CPR BU, CU, E, FAR | Quiz & scenario | Video, tour of an accident & emergency department |

| Jones et al., 2007 [9] | First Aid Professional | 1 | 20 | BLS, CPR | Practice in Manikin | Manikin |

| Connolly et al., 2007 [10] | Teachers | 1 | <120 | BLS, CPR | multiple choice questionnaire | Video & manikin |

| Hill et al., 2009 [11] | Not provided | 1 | 120 | CPR | Practice in manikin | Manikin |

| Toner et al., 2007 [12] | Teachers | 1 | 120 | BLS, CPR | multiple choice questionnaire | Video & manikin |

| Berthelot et al., 2013 [13] | First Aid Professional | 3 | 120 | CPR | questionnaire & Practice in manikin | Manikin |

| First Author, Year | Effect | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Bollig, 2009 [3] | C, B, OA, RP, ECR, ECI (p < 0.001) | Trained children have significantly better knowledge than children without training. |

| Lubrano, 2005 [4] | PBLS (p < 0.001) | Trained children with practical training to have a considerably better understanding than trained children without suitable training. |

| Uray, 2003 [5] | CO, CPR, T, RP, BU, D (rose 20–25%) | Trained children have significantly better knowledge than before training. |

| Banfai, 2017 [6] | BLS, AED, U, BL, EC (p < 0.01) | Trained children have significantly better knowledge and skills than before training. There was a significant correlation between chest compression depth and children’s age, weight, height, and body mass index. Ventilation depended on the same factors. |

| Fleischhackl, 2009 [7] | EC (95% success rate), CFVS (85% success rate), RP (70% success rate), CPR (86% success rate), AED (93% success rate) | Trained children can successfully and effectively learn BLS skills. Age did not influence the depth of chest compressions or tidal volume of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. The student’s BMI mostly controlled the depth of chest compressions or tidal volume during mouth-to-mouth ventilation. |

| Frederick, 2000 [8] | BLS, CPR, BU, CU, E, FAR (p < 0.01) | Trained children have a piece of significantly better knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behavior than children without training. |

| Jones, 2007 [9] | CCD (0% success rate) | Children (<11 years) were not strong enough to compress the chest to an adequate depth in simulated cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The compression depth is significantly associated with the pupils’ age, weight, and height. |

| Connolly, 2007 [10] | BLS, CPR (p < 0.001) | Trained children have significantly better knowledge than before training. |

| Hill, 2009 [11] | 15:2 vs. 30:2 (p < 0.001) | Children achieve greater depth of chest compressions when using a ratio of 15:2 rather than 30:2 |

| Toner, 2007 [12] | BLS, CPR (p < 0.001) | Trained children have substantially better ability than before training. |

| Berthelot, 2013 [13] | CCD (5% success rate) | Children (10–12 years) were not strong enough to compress the chest to an adequate depth in simulated cardiopulmonary resuscitation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tse, E.; Plakitsi, K.; Voulgaris, S.; Alexiou, G.A. The Role of a First Aid Training Program for Young Children: A Systematic Review. Children 2023, 10, 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030431

Tse E, Plakitsi K, Voulgaris S, Alexiou GA. The Role of a First Aid Training Program for Young Children: A Systematic Review. Children. 2023; 10(3):431. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030431

Chicago/Turabian StyleTse, Eleana, Katerina Plakitsi, Spyridon Voulgaris, and George A. Alexiou. 2023. "The Role of a First Aid Training Program for Young Children: A Systematic Review" Children 10, no. 3: 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030431