Autism and ADHD: A Literature Review Regarding Their Impacts on Parental Divorce

Abstract

1. Introduction

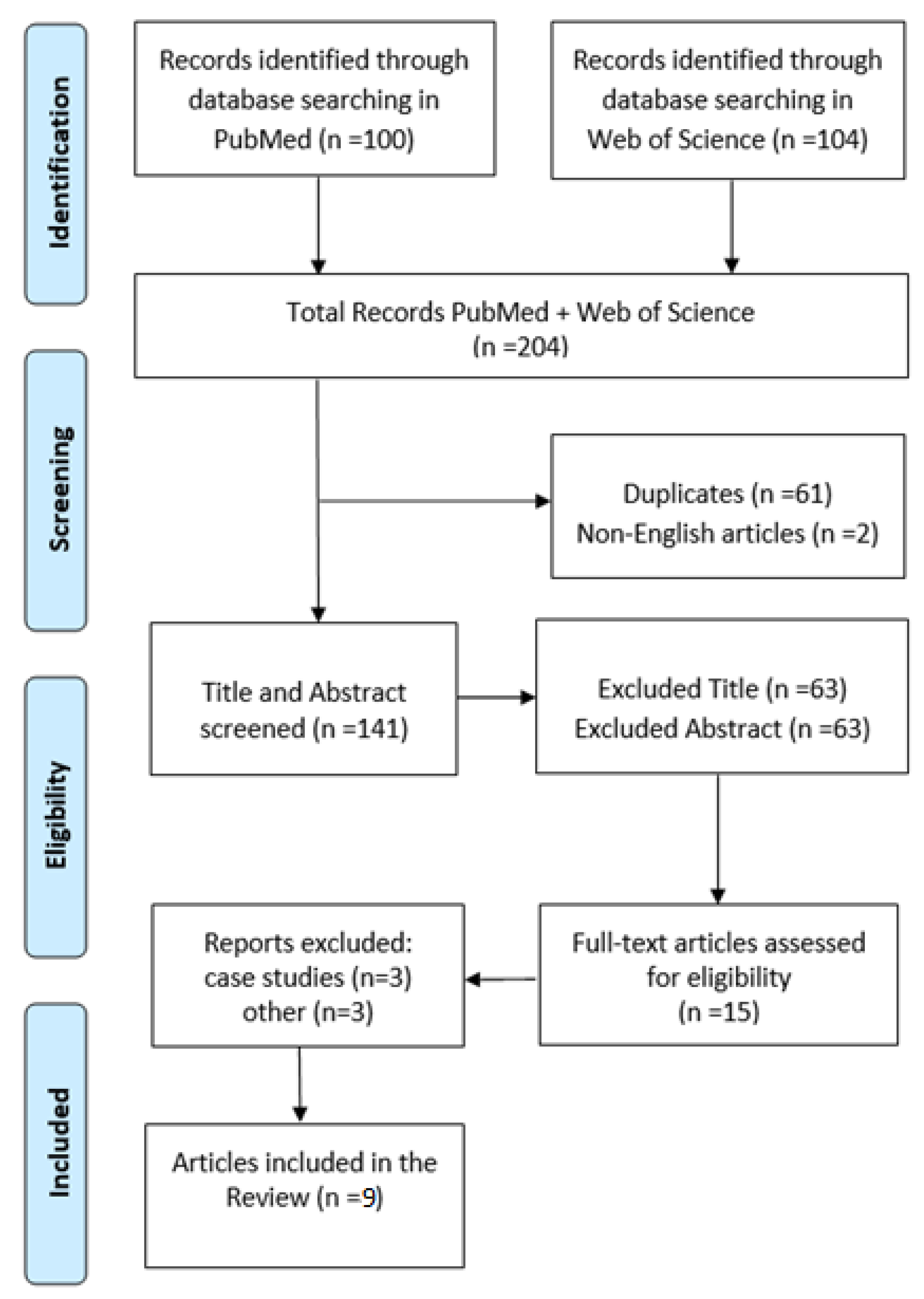

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. ADHD and Divorce

3.2. Autism and Divorce

4. Discussions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tabachnick, A.R.; He, Y.; Zajac, L.; Carlson, E.A.; Dozier, M. Secure attachment in infancy predicts context-dependent emotion expression in middle childhood. Emotion 2022, 22, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gewirtz, A.H.; Zamir, O. The impact of parental deployment to war on children: The crucial role of parenting. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 2014, 46, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posada, G.; Lü, T.; Trumbell, J.; Kaloustian, G.; Trudel, M.; Plata, S.J.; Peña, P.P.; Perez, J.; Tereno, S.; Dugravier, R.; et al. Is the Secure Base Phenomenon Evident Here, There, and Anywhere? A Cross-Cultural Study of Child Behavior and Experts’ Definitions. Child Dev. 2013, 84, 1896–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammes, P.S.; Crepaldi, M.A.; Bigras, M. Family Functioning and Socioaffective Competencies of Children in the Beginning of Schooling. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herke, M.; Knöchelmann, A.; Richter, M. Health and Well-Being of Adolescents in Different Family Structures in Germany and the Importance of Family Climate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, J.; Parke, R.D.; Butkovsky, L.; Braungart, J.M. Family-Peer Connections: The Roles of Emotional Expressiveness within the Family and Children’s Understanding of Emotions. Child Dev. 1992, 63, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litterbach, E.-K.V.; Campbell, K.J.; Spence, A.C. Family meals with young children: An online study of family mealtime characteristics, among Australian families with children aged six months to six years. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, S.; Olsen, S.O.; Honkanen, P. The role of family communication and parents’ feeding practices in children’s food preferences. Appetite 2015, 89, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakha, A.H.; Albahadel, D.M.; Saleh, H.A. Developing an active lifestyle for children considering the Saudi vision 2030: The family’s point of view. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, B.J.; Borduin, C.M.; Cone, L.T.; Borduin, B.J.; Sylvester, C.E. Children’s Concepts of the Family. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1992, 31, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, K.R.; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Communications; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds. Pediatrics 2007, 119, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, P.T.; Cummings, E.M. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinsorge, C.; Covitz, L.M. Impact of Divorce on Children: Developmental Considerations. Pediatr. Rev. 2012, 33, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, M. Schuld und Schuldgefühl im Zusammenhang mit Trennung und Scheidung [Guilt and subjective feelings of guilt in the context of separation and divorce]. Prax. Der Kinderpsychol. Und Kinderpsychiatr. 2001, 50, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, R.; van der Valk, I.E.; Deković, M.; Branje, S. Triangulation and child adjustment after parental divorce: Underlying mechanisms and risk factors. J. Fam. Psychol. 2022, 36, 1117–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spremo, M. Children and Divorce. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020, 32 (Suppl. 3), 353–359. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, A.K.; Robson, L.M. Children of Divorce. J. R. Soc. Health 1990, 110, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaksen, H. The effects of parental divorce on children. Psychiatriki 2021, 33, 81–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes-Costa, R.A.; Lamela, D.J.P.V.; Figueiredo, B.F.C. Psychosocial adjustment and physical health in children of divorce. J. Pediatr. 2009, 85, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, S.L.; Barker, E.T.; Seltzer, M.M.; Floyd, F.; Greenberg, J.; Orsmond, G.; Bolt, D. The relative risk and timing of divorce in families of children with an autism spectrum disorder. J. Fam. Psychol. 2010, 24, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, T.J. The Pathogenesis of Autism. Clin. Pathol. 2008, 1, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, C.; Elsabbagh, M.; Baird, G.; Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet 2018, 392, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodak, T.; Bergmann, S. Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 67, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happé, F.; Frith, U. The Weak Coherence Account: Detail-focused Cognitive Style in Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2006, 36, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fodstad, J.C.; Rojahn, J.; Matson, J.L. The Emergence of Challenging Behaviors in At-Risk Toddlers with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2012, 24, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludlow, A.; Skelly, C.; Rohleder, P. Challenges faced by parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 17, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearss, K.; Johnson, C.; Handen, B.; Smith, T.; Scahill, L. A Pilot Study of Parent Training in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Disruptive Behavior. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 43, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, B.J.; Mackintosh, V.H.; Goin-Kochel, R.P. My greatest joy and my greatest heartache: Parents’ own words on how having a child in the autism spectrum has affected their lives and their families’ lives. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2009, 3, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harold, G.T.; Leve, L.D.; Barrett, D.; Elam, K.; Neiderhiser, J.M.; Natsuaki, M.N.; Shaw, D.S.; Reiss, D.; Thapar, A. Biological and rearing mother influences on child ADHD symptoms: Revisiting the developmental interface between nature and nurture. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harold, G.T.; Leve, L.D.; Elam, K.K.; Thapar, A.; Neiderhiser, J.M.; Natsuaki, M.N.; Shaw, D.S.; Reiss, D. The nature of nurture: Disentangling passive genotype–environment correlation from family relationship influences on children’s externalizing problems. J. Fam. Psychol. 2013, 27, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, A.; DeMayo, M.M.; Glozier, N.; Guastella, A.J. An Overview of Autism Spectrum Disorder, Heterogeneity and Treatment Options. Neurosci. Bull. 2017, 33, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, C.; Mash, E.J. Families of Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Review and Recommendations for Future Research. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 4, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortese, S.; Coghill, D. Twenty years of research on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Looking back, looking forward. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2018, 21, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Couture, J. A Review of the Pathophysiology, Etiology, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Ann. Pharmacother. 2013, 48, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripp, G.; Wickens, J.R. Neurobiology of ADHD. Neuropharmacology 2009, 57, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.Q. A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychol. Rev. 1968, 75, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechtman, L. Families of Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Review. Can. J. Psychiatry 1996, 41, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinshaw, S.P. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Controversy, Developmental Mechanisms, and Multiple Levels of Analysis. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 14, 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coxe, S.; Sibley, M.H.; Becker, S.P. Presenting problem profiles for adolescents with ADHD: Differences by sex, age, race, and family adversity. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2020, 26, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, J.; Polanczyk, G.V.; Sonuga-Barke, E. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet 2020, 395, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermerhorn, A.C.; D’Onofrio, B.M.; Slutske, W.S.; Emery, R.E.; Turkheimer, E.; Harden, K.P.; Heath, A.C.; Martin, N.G. Offspring ADHD as a Risk Factor for Parental Marital Problems: Controls for Genetic and Environmental Confounds. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2012, 15, 700–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.R.; Farokhzadi, F.; Alipour, A.; Rostami, R.; Dehestani, M.; Salmanian, M. Marital Satisfaction amongst Parents of Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Normal Children. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2012, 7, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Neece, C.L.; Green, S.A.; Baker, B.L. Parenting Stress and Child Behavior Problems: A Transactional Relationship Across Time. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 117, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchaine, T.P.; McNulty, T. Comorbidities and continuities as ontogenic processes: Toward a developmental spectrum model of externalizing psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2013, 25, 1505–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, G.R. Coercive Family Process; Castalia: Eugene, OR, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.T.; Pacini, J.N. Perceived family functioning, marital status, and depression in parents of boys with at-tention deficit disorder. J. Learn. Disabil. 1989, 22, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymbs, B.T.; Pelham, W.E., Jr.; Molina, B.S.; Gnagy, E.M.; Wilson, T.K.; Greenhouse, J.B. Rate and predictors of divorce among parents of youths with ADHD. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvist, A.P.; Nielsen, H.S.; Simonsen, M. The importance of children’s ADHD for parents’ relationship stability and labor supply. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 88, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckel, L.; Clarke, A.; Barry, R.; McCarthy, R.; Selikowitz, M. The relationship between divorce and the psychological well-being of children with ADHD: Differences in age, gender, and subtype. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2009, 14, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalb, L.G.; Holingue, C.; Pfeiffer, D.; Reetzke, R.; Dillon, E.; Azad, G.; Freedman, B.; Landa, R. Parental relationship status and age at autism spectrum disorder diagnosis of their child. Autism 2021, 25, 2189–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, B.H.; Kalb, L.G.; Zablotsky, B.; Stuart, E. Relationship Status Among Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Population-Based Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2011, 42, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H. (Ed.) Parenting Infants. In Handbook of Parenting, Volume 1: Children and Parenting, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, N.; Frenn, M.; Feetham, S.; Simpson, P. Autism spectrum disorder: Parenting stress, family functioning and health-related quality of life. Fam. Syst. Health 2011, 29, 232–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, N.O.; Carter, A.S. Parenting Stress in Mothers and Fathers of Toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Associations with Child Characteristics. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2008, 38, 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecavalier, L.; Leone, S.; Wiltz, J. The impact of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2006, 50, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losada-Puente, L.; Baña, M.; Asorey, M.J.F. Family quality of life and autism spectrum disorder: Comparative diagnosis of needs and impact on family life. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 124, 104211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertule, D.; Vetra, A. The family needs of parents of preschool children with cerebral palsy: The impact of child’s gross motor and communications functions. Medicina 2014, 50, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.; Hastings, R.P.; Daley, D.; Stevenson, J. Pro-social behaviour and behaviour problems independently predict maternal stress. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2004, 29, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonis, S. Stress and Parents of Children with Autism: A Review of Literature. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 37, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, J.M.; Rodrigues, T.A.; Neta, M.M.R.; Damasceno, C.K.C.S.; Sousa, K.H.J.F.; Arisawa, E.L.S. Experiences of family members of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2021, 42, e20200437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadan, H.; Halle, J.W.; Ebata, A.T. Families with Children Who Have Autism Spectrum Disorders: Stress and Support. Except. Child. 2010, 77, 7–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.S.; Bordin, I.A.; Yazigi, L.; Mooney, J. Factors associated with stress in mothers of children with autism. Autism 2005, 9, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraone, S.V.; Asherson, P.; Banaschewski, T.; Biederman, J.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A.; Rohde, L.A.; Sonuga-Barke, E.J.; Tannock, R.; Franke, B. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrdp201520 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Montes, G.; Halterman, J.S. Psychological functioning and coping among mothers of children with autism: A pop-ulation-based study. Pediatrics 2007, 119, e1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva LM, T.; Schalock, M. Autism Parenting Stress Index: Initial psychometric evidence. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braddock, B.; Twyman, K. Access to Treatment for Toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Clin. Pediatr. 2014, 53, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowska, A.; Pisula, E. Parenting stress and coping styles in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism and Down syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2010, 54, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, E.L.; Gray, K.M.; Tonge, B.J. Early features of autism: Repetitive behaviors in young children. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 15, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moh, T.A.; Magiati, I. Factors associated with parental stress and satisfaction during the process of diagnosis of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altiere, M.J.; von Kluge, S. Searching for acceptance: Challenges encountered while raising a child with autism. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 34, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nealy, C.E.; O’Hare, L.; Powers, J.D.; Swick, D.C. The Impact of Autism Spectrum Disorders on the Family: A Qualitative Study of Mothers’ Perspectives. J. Fam. Soc. Work. 2012, 15, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, H.R.; Patterson, B.J.; Klein, J. Coping with Autism: A Journey Toward Adaptation. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2012, 27, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely-Barnes, S.L.; Hall, H.R.; Roberts, R.J.; Graff, J.C. Parenting a Child with an Autism Spectrum Disorder: Public Perceptions and Parental Conceptualizations. J. Fam. Soc. Work. 2011, 14, 208–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, M.E.; Burbine, T.; Bowers, C.A.; Tantleff-Dunn, S. Moderators of Stress in Parents of Children with Autism. Community Ment. Health J. 2001, 37, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koegel, L.K.; Koegel, R.L.; Hurley, C.; Frea, W.D. Improving social skills and disruptive behavior in children with autism through self-management. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1992, 25, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.; Totsika, V.; Hastings, R.P.; Petalas, M.A. Gender differences when parenting children with autism spec-trum disorders: A multilevel modeling approach. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 2090–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill-Chapman, C.R.; Herzog, T.K.; Maduro, R.S. Aligning over the child: Parenting alliance mediates the association of autism spectrum disorder atypicality with parenting stress. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 1498–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, B.; Hambrick, D.Z. The relationship between the broader autism phenotype, child severity, and stress and depression in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2011, 5, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holroyd, J.; McArthur, D. Mental retardation and stress on the parents: A contrast between Down’s syndrome and childhood autism. Am. J. Ment. Defic. 1976, 80, 431–436. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S.; Bremer, E.; Lloyd, M. Autism spectrum disorder: Family quality of life while waiting for intervention services. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 26, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, E.; Jahoda, A.; Knott, F. Mothers’ attributions following their child’s diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder: Exploring links with maternal levels of stress, depression, and expectations about their child’s future. Autism 2006, 10, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, S.; Gray, K.; Taffe, J.; Tonge, B.; Sweeney, D.; Einfeld, S. Behaviour and emotional problems in toddlers with pervasive developmental disorders and developmental delay: Associations with parental mental health and family functioning. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2006, 50, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, R.P.; Kovshoff, H.; Brown, T.; Ward, N.J.; Degli Espinosa, F.; Remington, B. Coping strategies in mothers and fathers of preschool and school-age children with autism. Autism 2005, 9, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, E.J.; Nix, R.L.; Hartley, S.L. Family Emotional Climate and Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 3244–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, I.; Koller, J.; Lebowitz, E.R.; Shulman, C.; Ben Itzchak, E.; Zachor, D.A. Family Accommodation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 3602–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottie, C.G.; Cohen, J.; Ingram, K.M. Parenting a Child with Autism: Contextual Factors Associated with Enhanced Daily Parental Mood. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2008, 34, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekhet, A.K.; Johnson, N.L.; Zauszniewski, J.A. Resilience in Family Members of Persons with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review of the Literature. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautakoski, P.; Ursin, P.A.; Carter, A.S.; Kaljonen, A.; Nylund, A.; Pihlaja, P. Communication Skills Predict Social-Emotional Competencies. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021992421000617 (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Gray, D.E. Coping over time: The parents of children with autism. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2006, 50, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, D.M.; Flory, J.D.; Miller, C.J.; Halperin, J.M. Maternal positive parenting style is associated with better functioning in hyperactive/inattentive preschool children. Infant Child Dev. 2011, 20, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinshaw, S.P.; Zupan, B.A.; Simmel, C.; Nigg, J.T.; Melnick, S.M. Peer status in boys with and without attention-deficit hyper-activity disorder: Predictions from overt and covert antisocial behavior, social isolation, and authoritative parenting beliefs. Child Dev. 1997, 64, 880–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtig, T.; Ebeling, H.; Taanila, A.; Miettunen, J.; Smalley, S.; McGough, J.; Loo, S.; Järvelin, M.-R.; Moilanen, I. ADHD and comorbid disorders in relation to family environment and symptom severity. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2007, 16, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deater-Deckard, K. Parents’ and Children’s ADHD in a Family System. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2017, 45, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mash, E.J.; Johnston, C. Parental perceptions of child behavior problems, parenting self-esteem, and mothers’ reported stress in younger and older hyperactive and normal children. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983, 51, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R.A. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 121, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Query Terms |

|---|---|

| PubMed | “Autism” OR “autisms” OR “autistic disorder” OR “autistic” AND (“disorder” OR “autistic disorder” OR “autism”) AND (“divorce” OR “divorce” OR “divorced” OR “divorces” OR “divorcing”), AND (“attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity” OR (“attention” AND “deficit” AND “disorder” AND “hyperactivity”) OR (“attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity” OR “adhd”) AND (“divorce” OR “divorce” OR “divorced” OR “divorces” OR “divorcing”). |

| Web of Science |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anchesi, S.D.; Corallo, F.; Di Cara, M.; Quartarone, A.; Catalioto, R.; Cucinotta, F.; Cardile, D. Autism and ADHD: A Literature Review Regarding Their Impacts on Parental Divorce. Children 2023, 10, 438. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030438

Anchesi SD, Corallo F, Di Cara M, Quartarone A, Catalioto R, Cucinotta F, Cardile D. Autism and ADHD: A Literature Review Regarding Their Impacts on Parental Divorce. Children. 2023; 10(3):438. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030438

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnchesi, Smeralda Diandra, Francesco Corallo, Marcella Di Cara, Angelo Quartarone, Rino Catalioto, Francesca Cucinotta, and Davide Cardile. 2023. "Autism and ADHD: A Literature Review Regarding Their Impacts on Parental Divorce" Children 10, no. 3: 438. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030438

APA StyleAnchesi, S. D., Corallo, F., Di Cara, M., Quartarone, A., Catalioto, R., Cucinotta, F., & Cardile, D. (2023). Autism and ADHD: A Literature Review Regarding Their Impacts on Parental Divorce. Children, 10(3), 438. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030438