The Role of the Mind-Body Connection in Children with Food Reactions and Identified Adversity: Implications for Integrating Stress Management and Resilience Strategies in Clinical Practice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Setting

2.2. Patient Population

2.3. Stressors and Resilience

2.4. Integrative Medicine Use

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

3.2. Stressors

3.3. Resilience

3.4. Integrative Modalities

3.5. Asssociation between Stressors and Integrative Modalities

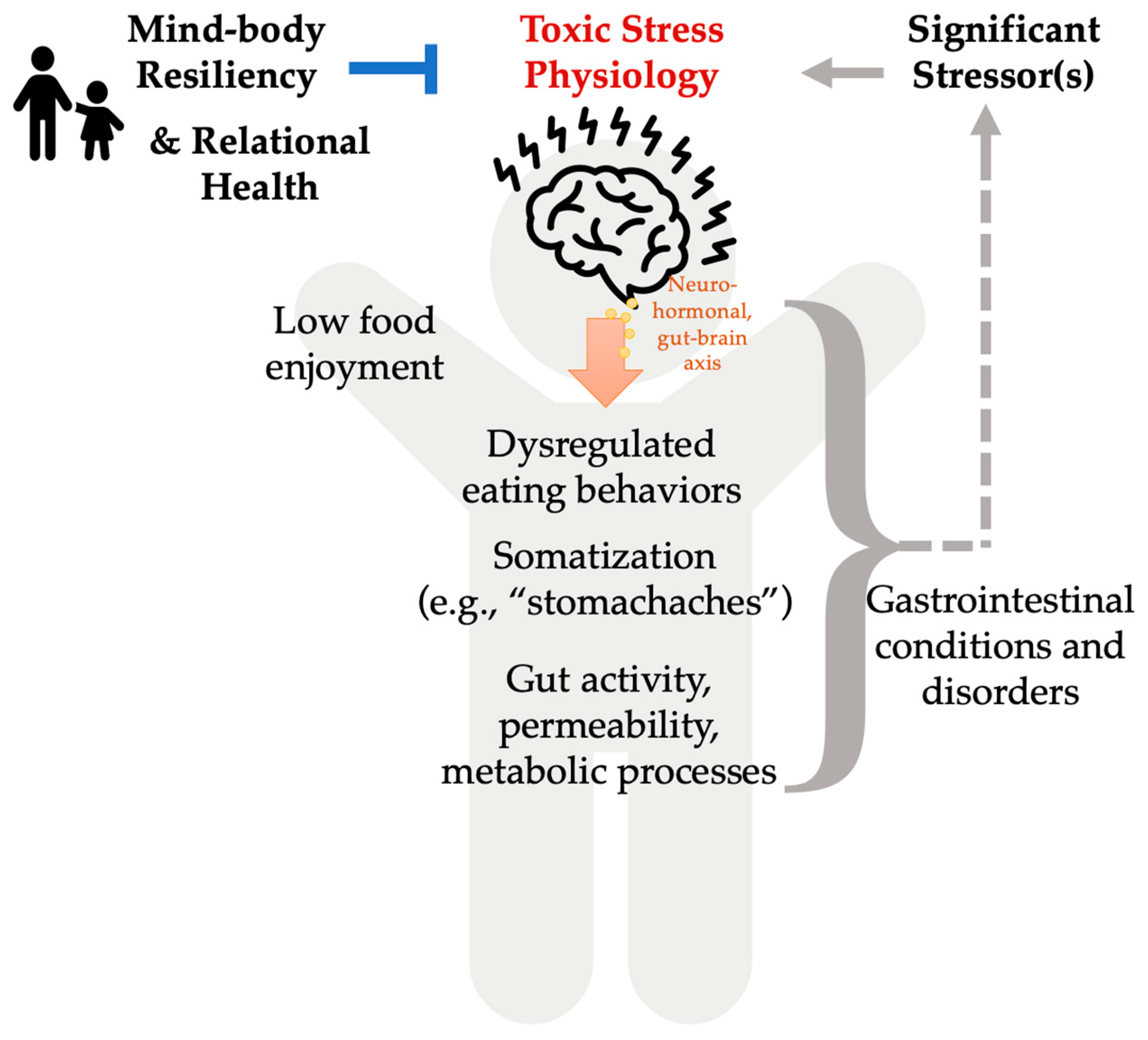

4. Discussion

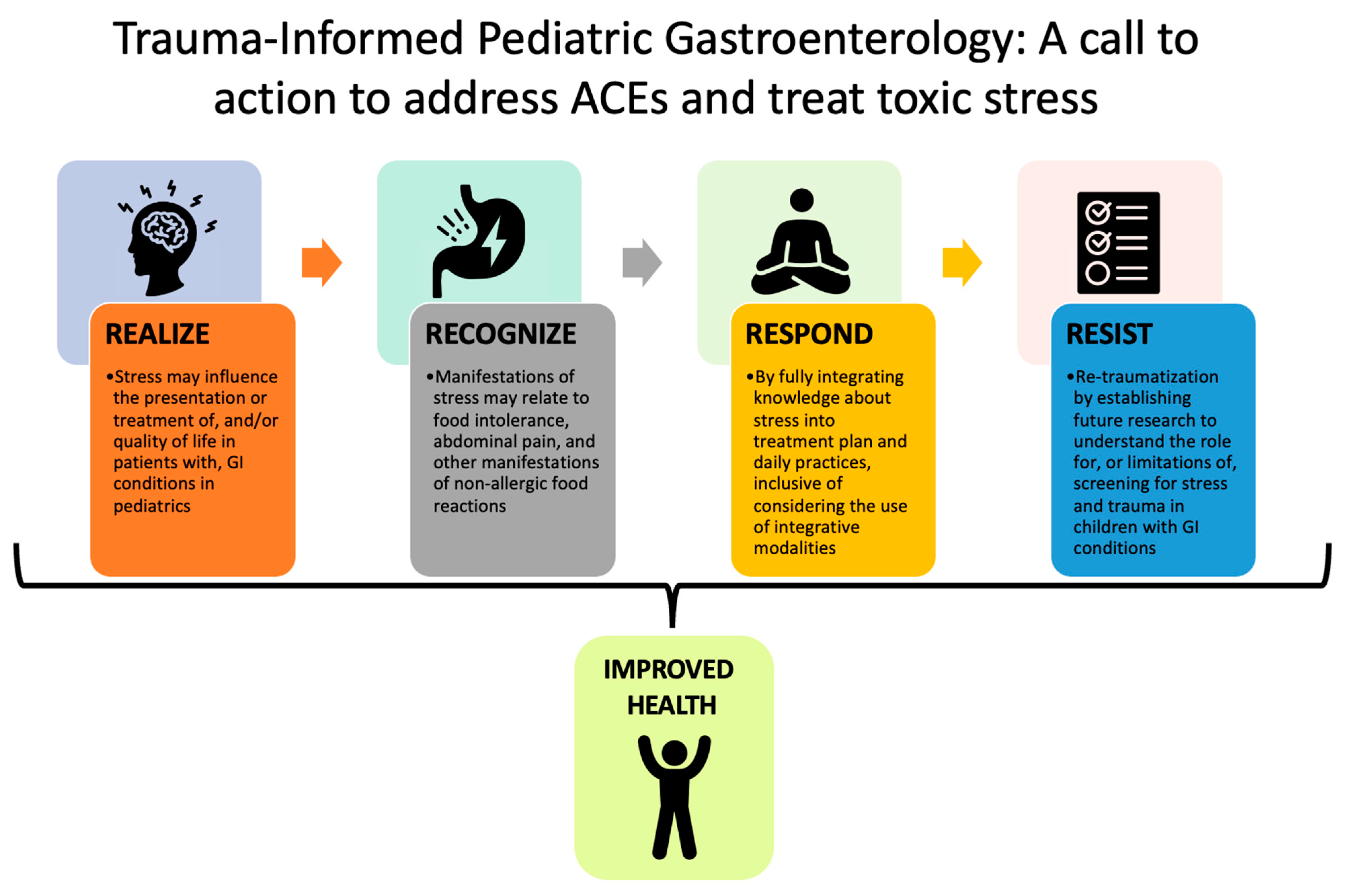

4.1. Literature, Gaps, and Opportunities

4.2. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lau, B.W. Stress in Chilren: Can Nurses Help? Pediatr. Nurs. 2002, 28, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, A.; Yogman, M. Preventing Childhood Toxic Stress: Partnering with Families and Communities to Promote Relational Health. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021052582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L. Review Article: Epidemiology and Quality of Life in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: REVIEW: EPIDEMIOLOGY AND QOL IN FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 20, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edman, J.S.; Greeson, J.M.; Roberts, R.S.; Kaufman, A.B.; Abrams, D.I.; Dolor, R.J.; Wolever, R.Q. Perceived Stress in Patients with Common Gastrointestinal Disorders: Associations with Quality of Life, Symptoms and Disease Management. Explore 2017, 13, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Hodgkinson, S.C.; Belcher, H.M.E.; Hyman, C.; Cooley-Strickland, M. Somatic Symptoms, Peer and School Stress, and Family and Community Violence Exposure among Urban Elementary School Children. J. Behav. Med. 2013, 36, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.C.; Moss, R.H.; Sykes-Muskett, B.; Conner, M.; O’Connor, D.B. Stress and Eating Behaviors in Children and Adolescents: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Appetite 2018, 123, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsenbruch, S.; Enck, P. The Stress Concept in Gastroenterology: From Selye to Today. F1000Res 2017, 6, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melinder, C.; Hiyoshi, A.; Kasiga, T.; Halfvarson, J.; Fall, K.; Montgomery, S. Resilience to Stress and Risk of Gastrointestinal Infections. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, L.M.; Lammert, A.; Phelan, S.; Ventura, A.K. Associations between Parenting Stress, Parent Feeding Practices, and Perceptions of Child Eating Behaviors during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Appetite 2022, 177, 106148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomer, M.C.E. Review Article: The Aetiology, Diagnosis, Mechanisms and Clinical Evidence for Food Intolerance. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 41, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqui, F.; Poli, C.; Colecchia, A.; Marasco, G.; Festi, D. Adverse Food Reaction and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Role of the Dietetic Approach. JGLD 2015, 24, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehr, C.C.; Edenharter, G.; Reimann, S.; Ehlers, I.; Worm, M.; Zuberbier, T.; Niggemann, B. Food Allergy and Non-Allergic Food Hypersensitivity in Children and Adolescents. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2004, 34, 1534–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, C.; Patil, V.; Grundy, J.; Glasbey, G.; Twiselton, R.; Arshad, S.H.; Dean, T. Prevalence and Cumulative Incidence of Food Hyper-Sensitivity in the First 10 Years of Life. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2016, 27, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, M.; Ekström, S.; Protudjer, J.L.P.; Bergström, A.; Kull, I. Living with Food Hypersensitivity as an Adolescent Impairs Health Related Quality of Life Irrespective of Disease Severity: Results from a Population-Based Birth Cohort. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsburg, M.D. Building Resilience in Children and Teens: Giving Kids Roots and Wings, 4th ed.; American Academy of Pediatrics: Itasca, IL, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-61002-385-6. [Google Scholar]

- Danese, A.; McEwen, B.S. Adverse Childhood Experiences, Allostasis, Allostatic Load, and Age-Related Disease. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 106, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babic, R.; Babic, M.; Rastovic, P.; Curlin, M.; Simic, J.; Mandic, K.; Pavlovic, K. Resilience in Health and Illness. Pyschiatria Danub. 2020, 32, 226–232. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, S.J.; Murrough, J.W.; Han, M.-H.; Charney, D.S.; Nestler, E.J. Neurobiology of Resilience. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 1475–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagone, E.; De Caroli, M.E.; Falanga, R.; Indiana, M.L. Resilience and Perceived Self-Efficacy in Life Skills from Early to Late Adolescence. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronen, T. The Role of Coping Skills for Developing Resilience Among Children and Adolescents. In The Palgrave Handbook of Positive Education; Kern, M.L., Wehmeyer, M.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 345–368. ISBN 978-3-030-64536-6. [Google Scholar]

- Karpinski, N.; Popal, N.; Plück, J.; Petermann, F.; Lehmkuhl, G. Freizeitaktivitäten, Resilienz und psychische Gesundheit von Jugendlichen. Z. Für Kinder-Jugendpsychiatrie Psychother. 2017, 45, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, S.D.; Matthews, K.A.; Cohen, S.; Martire, L.M.; Scheier, M.; Baum, A.; Schulz, R. Association of Enjoyable Leisure Activities with Psychological and Physical Well-Being. Psychosom. Med. 2009, 71, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bethell, C.; Gombojav, N.; Solloway, M.; Wissow, L. Adverse Childhood Experiences, Resilience and Mindfulness-Based Approaches. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 25, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dossett, M.L.; Cohen, E.M.; Cohen, J. Integrative Medicine for Gastrointestinal Disease. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2017, 44, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwermer, M.; Fetz, K.; Längler, A.; Ostermann, T.; Zuzak, T.J. Complementary, Alternative, Integrative and Dietary Therapies for Children with Crohn’s Disease—A Systematic Review. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 52, 102493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, R.; Sibinga, E. The Role of Mindfulness in Reducing the Adverse Effects of Childhood Stress and Trauma. Children 2017, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s in a Name; National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Carlson, L.E.; Toivonen, K.; Subnis, U. Integrative Approaches to Stress Management. Cancer J. 2019, 25, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed-Knight, B.; Claar, R.L.; Schurman, J.V.; van Tilburg, M.A.L. Implementing Psychological Therapies for Functional GI Disorders in Children and Adults. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 10, 981–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M.A.; Severi, C. The Gut-Brain Axis: Interactions between Enteric Microbiota, Central and Enteric Nervous Systems. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chernyak, N.; Kushnir, T. The Influence of Understanding and Having Choice on Children’s Prosocial Behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 20, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronson, M. Self-Regulation in Early Childhood: Nature and Nurture; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-1-57230-532-8. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—A Metadata-Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, E.V.; Carlini, S.V.; Gonzalez, I.; St. Hubert, S.; Linder, J.A.; Rigotti, N.A.; Kontos, E.Z.; Park, E.R.; Marinacci, L.X.; Haas, J.S. Accuracy of Race, Ethnicity, and Language Preference in an Electronic Health Record. J. Gen. Intern Med. 2015, 30, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, R.; Farrell-Bryan, D.; Gutierrez, G.; Boen, C.; Tam, V.; Yun, K.; Venkataramani, A.S.; Montoya-Williams, D. A Content Analysis of US Sanctuary Immigration Policies: Implications for Research in Social Determinants of Health: Study Examines US Sanctuary Immigration Policies and Implications for Social Determinants of Health Research. Health Affairs 2021, 40, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronholm, P.F.; Forke, C.M.; Wade, R.; Bair-Merritt, M.H.; Davis, M.; Harkins-Schwarz, M.; Pachter, L.M.; Fein, J.A. Adverse Childhood Experiences. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.E.; Pollak, S.D. Early Life Stress and Development: Potential Mechanisms for Adverse Outcomes. J. Neurodevelop. Disord. 2020, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yogman, M.; Garner, A.; Hutchinson, J.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Golinkoff, R.M.; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Council on Communications and Media; Baum, R.; Gambon, T.; Lavin, A.; et al. The Power of Play: A Pediatric Role in Enhancing Development in Young Children. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20182058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, J.; Sochacka, N.W.; Kellam, N.N. Quality in Interpretive Engineering Education Research: Reflections on an Example Study. J. Eng. Educ. 2013, 102, 626–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, E.G.; Thompson, R.; Dubowitz, H.; Harvey, E.M.; English, D.J.; Proctor, L.J.; Runyan, D.K. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Child Health in Early Adolescence. JAMA Pediatr. 2013, 167, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Białek-Dratwa, A.; Szymańska, D.; Grajek, M.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Szczepańska, E.; Kowalski, O. ARFID—Strategies for Dietary Management in Children. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEWEN, B.S. Stress, Adaptation, and Disease: Allostasis and Allostatic Load. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998, 840, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, M.; Marques, S.S.; Oh, D.; Harris, N.B. Toxic Stress in Children and Adolescents. Adv. Pediatr. 2016, 63, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suglia, S.F.; Koenen, K.C.; Boynton-Jarrett, R.; Chan, P.S.; Clark, C.J.; Danese, A.; Faith, M.S.; Goldstein, B.I.; Hayman, L.L.; Isasi, C.R.; et al. Childhood and Adolescent Adversity and Cardiometabolic Outcomes: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 137, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, R.; Zhao, S.; Kline, D.M.; Brock, G.; Carroll, J.E.; Seeman, T.E.; Jaffee, S.R.; Berger, J.S.; Golden, S.H.; Carnethon, M.R.; et al. Childhood Environment Early Life Stress, Caregiver Warmth, and Associations with the Cortisol Diurnal Curve in Adulthood: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2023, 149, 106008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stengel, A.; Taché, Y. Neuroendocrine Control of the Gut During Stress: Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Signaling Pathways in the Spotlight. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2009, 71, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilgoff, R.; Singh, L.; Koita, K.; Gentile, B.; Marques, S.S. Adverse Childhood Experiences, Outcomes, and Interventions. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 67, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, D.L.; Silver, E.J.; Stein, R.E.K. Effects of Yoga on Inner-City Children’s Well-Being: A Pilot Study. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2009, 15, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Johannesson, E.; Simrén, M.; Strid, H.; Bajor, A.; Sadik, R. Physical Activity Improves Symptoms in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultchen, D.; Reichenberger, J.; Mittl, T.; Weh, T.R.M.; Smyth, J.M.; Blechert, J.; Pollatos, O. Bidirectional Relationship of Stress and Affect with Physical Activity and Healthy Eating. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, K.; O’Neill, S.; Dockray, S. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Mindfulness Interventions on Cortisol. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 2108–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristori, M.V.; Quagliariello, A.; Reddel, S.; Ianiro, G.; Vicari, S.; Gasbarrini, A.; Putignani, L. Autism, Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Modulation of Gut Microbiota by Nutritional Interventions. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.; Lane, M.; Hockey, M.; Aslam, H.; Berk, M.; Walder, K.; Borsini, A.; Firth, J.; Pariante, C.M.; Berding, K.; et al. Diet and Depression: Exploring the Biological Mechanisms of Action. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethell, C.; Jones, J.; Gombojav, N.; Linkenbach, J.; Sege, R. Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Mental and Relational Health in a Statewide Sample: Associations Across Adverse Childhood Experiences Levels. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, e193007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgermeister, D. Childhood Adversity: A Review of Measurement Instruments. J. Nurs. Meas. 2007, 15, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, N.; Hessler, D.; Koita, K.; Ye, M.; Benson, M.; Gilgoff, R.; Bucci, M.; Long, D.; Burke Harris, N. Pediatrics Adverse Childhood Experiences and Related Life Events Screener (PEARLS) and Health in a Safety-Net Practice. Child. Abus. Negl. 2020, 108, 104685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Fink, L.; Handelsman, L.; Foote, J. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, J.R.; Caspi, A.; Meehan, A.J.; Ambler, A.; Arseneault, L.; Fisher, H.L.; Harrington, H.; Matthews, T.; Odgers, C.L.; Poulton, R.; et al. Population vs Individual Prediction of Poor Health from Results of Adverse Childhood Experiences Screening. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, T.L. Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in Primary Care: A Cautionary Note. JAMA 2020, 323, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach; SAMHSA: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014.

| Variable | Variable Category | Participants by Category, n (%, N = 130) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | N = 130 | |

| Gender | Male, n (%) Female, n (%) | 74 (57%) 56 (43%) |

| Average Age * | 10.36 years | |

| Race | White, n (%) Asian, n (%) Black or African American, n (%) Unknown or Not Reported, n (%) | 98 (75%) 10 (8%) 5 (4%) 17 (13%) |

| Ethnicity | Not Hispanic or Latino, n (%) Hispanic or Latino, n (%) Unknown or Not Reported, n (%) | 125 (96%) 3 (2%) 2 (2%) |

| Stress, Resilience, and Integrative Modality Use | Participants with Stressors, n (%) 1 stressor, n 2 stressors, n 3 stressors, n Participants with Resilience Strategies, n (%) Participants with Integrative Modalities Upon Intake, n (%) Participants with Integrative Modalities Prescribed, n (%) | 98 (75%) 58 34 6 98 (75%) 69 (52%) 110 (85%) |

| Code | n (%, N = 98) | Chart Example |

|---|---|---|

| Medical | 50 (51%) | “Doctors’ visits and tests” “GI symptoms” “Medical problems (limited diet and being sick often)” |

| Mental Health | 20 (20%) | “After school tends to be tough emotionally (weekends differ)” “Reports difficulty relaxing—stressors are his anxiety and OCD” |

| School—Other | 19 (19%) | “Change of school” “School does not see as an important health issue that needs accommodation” |

| Family—Other | 14 (14%) | “Hates to be separated from mom” “Conflict with sister and aggression; noncompliance” |

| School—Learning | 11 (11%) | “Poor performance in school [is causing stress]” “Learning disability, anxiety, lack of focus, hyperactivity, self-stimulatory activities [while in school]” |

| Family—Parents | 11 (11%) | “Parenting differences—dad is in a lot of denial about the symptoms they’ve had to deal with for the past 6–7 years, mom is actively trying to recover her own health, they are in counseling to work through issues and asked for guidance to get their daughter to the next stages” “Volatile relationship with father” |

| Behavioral | 9 (9%) | Mom reports “impulsive, hyperactive, eating issues, wet bed, emotion control, attention issues” |

| School—Bullying | 5 (5%) | “Bullying at school a little” “Change of school, bullying” |

| Financial | 2 (2%) | “College and lack of a job” |

| Recent Move | 2 (2%) | “Stressors: change of school, recent family move” “Recent family move” |

| Stressors—Y (n = 98) | Stressors—N (n = 32) | |

|---|---|---|

| Integrative Methods—Y | 59 (60%) | 10 (31%) |

| Integrative Methods—N | 39 (40%) | 22 (69%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, O.; Mascarenhas, M.; Miccio, R.; Brown-Whitehorn, T.; Dean, A.; Erlichman, J.; Ortiz, R. The Role of the Mind-Body Connection in Children with Food Reactions and Identified Adversity: Implications for Integrating Stress Management and Resilience Strategies in Clinical Practice. Children 2023, 10, 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030563

Lee O, Mascarenhas M, Miccio R, Brown-Whitehorn T, Dean A, Erlichman J, Ortiz R. The Role of the Mind-Body Connection in Children with Food Reactions and Identified Adversity: Implications for Integrating Stress Management and Resilience Strategies in Clinical Practice. Children. 2023; 10(3):563. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030563

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Olivia, Maria Mascarenhas, Robin Miccio, Terri Brown-Whitehorn, Amy Dean, Jessi Erlichman, and Robin Ortiz. 2023. "The Role of the Mind-Body Connection in Children with Food Reactions and Identified Adversity: Implications for Integrating Stress Management and Resilience Strategies in Clinical Practice" Children 10, no. 3: 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030563

APA StyleLee, O., Mascarenhas, M., Miccio, R., Brown-Whitehorn, T., Dean, A., Erlichman, J., & Ortiz, R. (2023). The Role of the Mind-Body Connection in Children with Food Reactions and Identified Adversity: Implications for Integrating Stress Management and Resilience Strategies in Clinical Practice. Children, 10(3), 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030563