Experiences and Perspectives of Children and Young People Living with Childhood-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus—An Integrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

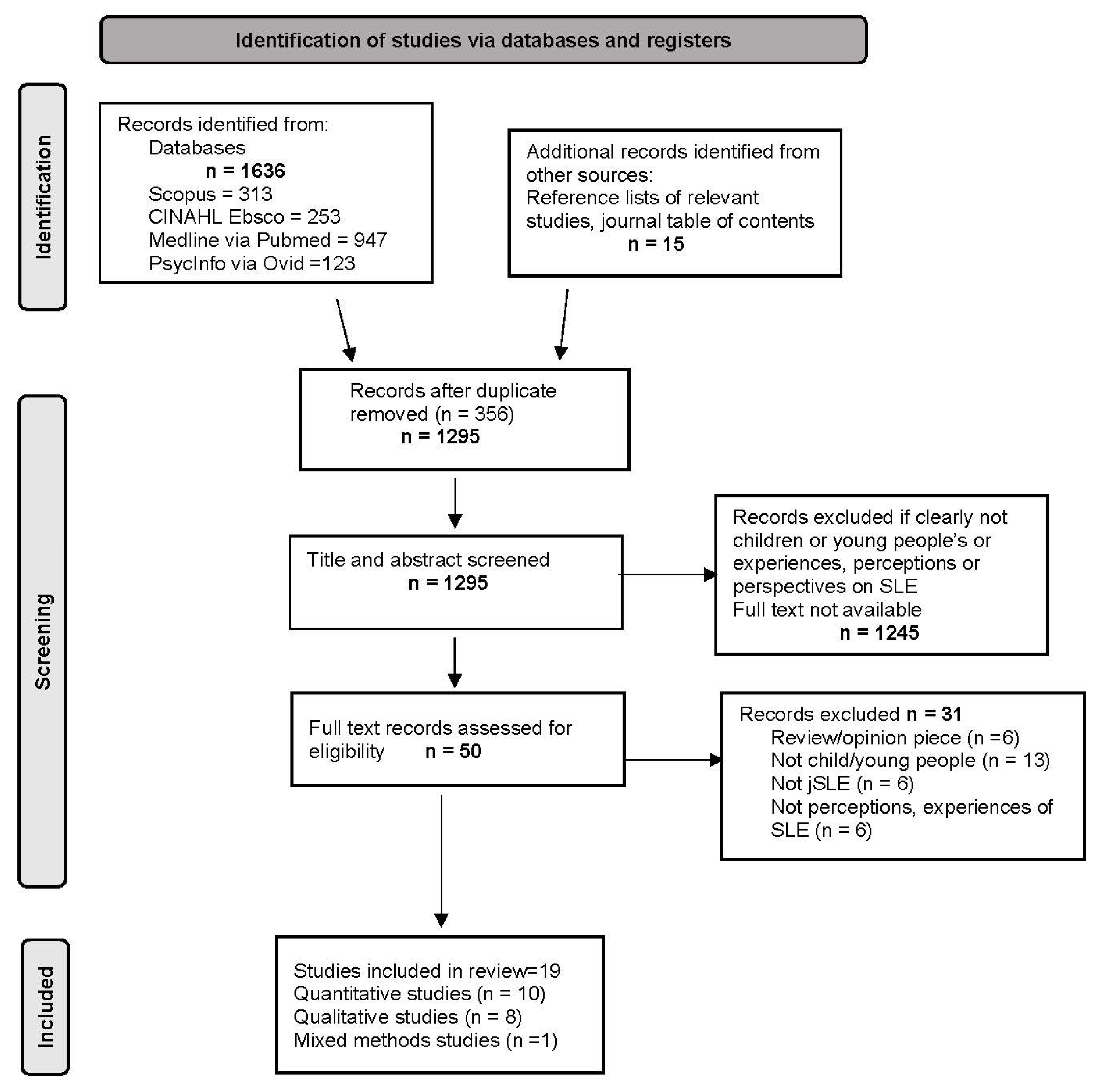

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Problem Identification and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Quality Appraisal

2.4. Data Management and Extraction

2.5. Data Synthesis and Analysis

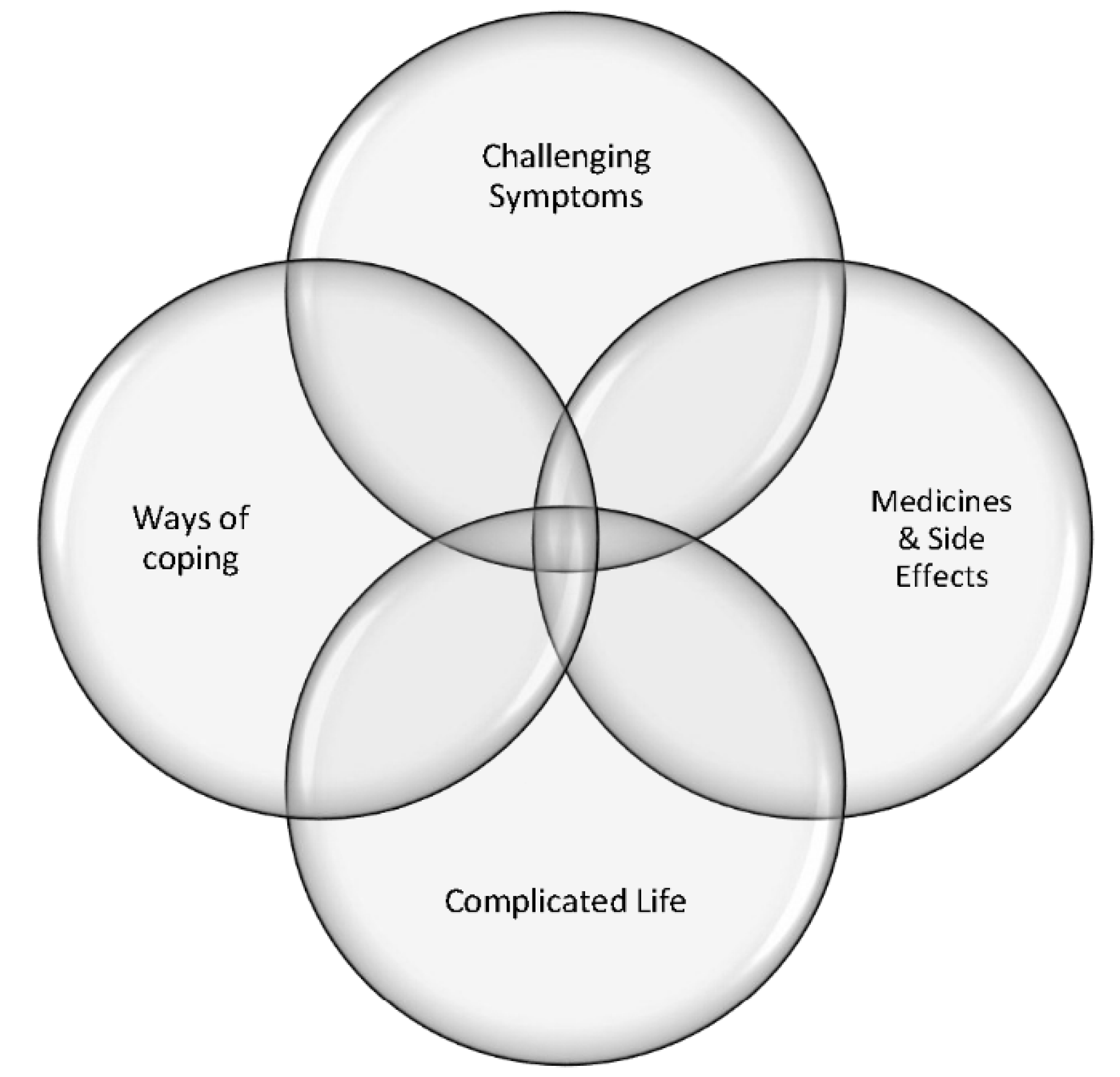

3. Results

4. Challenging Symptoms

5. Medicines and Side Effects

6. Complicated Life

7. Ways of Coping

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silva, C.A.; Avcin, T.; Brunner, H.I. Taxonomy for systemic lupus erythematosus with onset before adulthood. Arthritis Care Res. 2012, 64, 1787–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.M.D.; Lythgoe, H.; Midgley, A.; Beresford, M.W.; Hedrich, C.M. Juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: Update on clinical presentation, pathophysiology and treatment options. Clin. Immunol. 2019, 209, 108274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, D.; O’Connor, C.; Nertney, L.; MacDermott, E.J.; Mullane, D.; Franklin, O.; Killeen, O.G. Juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus presenting as pancarditis. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 2019, 17, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiraki, L.T.; Feldman, C.H.; Liu, J.; Alarcón, G.S.; Fischer, M.A.; Winkelmayer, W.C.; Costenbader, K.H. Prevalence, incidence, and demographics of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis from 2000 to 2004 among children in the US medicaid beneficiary population. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 64, 2669–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineles, D.; Valente, A.; Warren, B.; Peterson, M.; Lehman, T.; Moorthy, L. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of pediatric onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2011, 20, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huemer, C.; Huemer, M.; Dorner, T.; Falger, J.; Schacherl, H.; Bernecker, M.; Artacker, G.; Pilz, I. Incidence of pediatric rheumatic diseases in a regional population in Austria. J. Rheumatol. 2001, 28, 2116–2119. [Google Scholar]

- Concannon, A.; Rudge, S.; Yan, J.; Reed, P. The incidence, diagnostic clinical manifestations and severity of juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus in New Zealand Maori and Pacific Island children: The Starship experience (2000−2010). Lupus 2013, 22, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golder, V.; Tsang-A-Sjoe, M.W.P. Treatment targets in SLE: Remission and low disease activity state. Rheumatology 2020, 59 (Suppl. S5), v19–v28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, H.I.; Gladman, D.D.; Ibañez, D.; Urowitz, M.D.; Silverman, E.D. Difference in disease features between childhood-onset and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, L.B.; Uribe, A.G.; Fernández, M.; Vilá, L.M.; McGwin, G.; Apte, M.; Fessler, B.J.; Bastian, H.M.; Reveille, J.D.; Alarcón, G.S. Adolescent onset of lupus results in more aggressive disease and worse outcomes: Results of a nested matched case-control study within LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA LVII). Lupus 2008, 17, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, G.; Ambrose, N. The management of lupus in young people. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 68, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Sayyed, Z.; Ameer, M.A.; Arif, A.W.; Kiran, F.; Iftikhar, A.; Iftikhar, W.; Ahmad, M.Q.; Malik, M.B.; Kumar, V.; et al. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: An Overview of the Disease Pathology and Its Management. Cureus 2018, 10, e3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D., Jr.; Aguilar, D.; Schoenwetter, M.; Dubois, R.; Russak, S.; Ramsey-Goldman, R.; Navarra, S.; Hsu, B.; Revicki, D.; Cella, D.; et al. Impact of systemic lupus erythematosus on health, family, and work: The patient perspective. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelin, E.; Yazdany, J.; Trupin, L. Relationship Between Poverty and Mortality in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res. 2018, 70, 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatto, M.; Zen, M.; Iaccarino, L.; Doria, A. New therapeutic strategies in systemic lupus erythematosus management. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2019, 15, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farinha, F.; Freitas, F.; Águeda, A.; Cunha, I.; Barcelos, A. Concerns of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and adherence to therapy—A qualitative study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2017, 11, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesińska, M.; Saletra, A. Quality of life in systemic lupus erythematosus and its measurement. Reumatologia 2018, 56, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gomez, A.; Qiu, V.; Cederlund, A.; Borg, A.; Lindblom, J.; Emamikia, S.; Enman, Y.; Lampa, J.; Parodis, I. Adverse Health-Related Quality of Life Outcome Despite Adequate Clinical Response to Treatment in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 651249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugni, V.M.; Ozaki, L.S.; Okamoto, K.Y.; Barbosa, C.M.; Hilário, M.O.; Len, C.A.; Terreri, M.T. Factors associated with adherence to treatment in children and adolescents with chronic rheumatic diseases. J. Pediatr. 2012, 88, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costedoat-Chalumeau, N.; Pouchot, J.; Guettrot-Imbert, G.; Le Guern, V.; Leroux, G.; Marra, D.; Morel, N.; Piette, J.C. Adherence to treatment in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013, 27, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciosek, A.L.; Makris, U.E.; Kramer, J.; Bermas, B.L.; Solow, E.B.; Wright, T.; Bitencourt, N. Health Literacy and Patient Activation in the Pediatric to Adult Transition in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Patient and Health Care Team Perspectives. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2022, 4, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinstein, T.B.; Knight, A.M. Disparities in Childhood-Onset Lupus. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 46, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fair, D.C.; Rodriguez, M.; Knight, A.M.; Rubinstein, T.B. Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Current Insights and Impact on Quality of Life, A Systematic Review. Open Access Rheumatol. 2019, 11, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.M.; Rubinstein, T.B.; Rodriguez, M.; Knight, A.M. Mental health care for youth with rheumatologic diseases—Bridging the gap. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 2017, 15, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treemarcki, E.B.; Danguecan, A.N.; Cunningham, N.R.; Knight, A.M. Mental Health in Pediatric Rheumatology: An Opportunity to Improve Outcomes. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 48, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.M.D.; Egbivwie, N.; Cowan, K.; Ramanan, A.V.; Pain, C.E. Research priority setting for paediatric rheumatology in the UK. Lancet Rheumatol. 2022, 4, e517–e524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, N.; Shaikhani, D.; Teng, Y.K.O.; de Leeuw, K.; Bijl, M.; Dolhain, R.; Zirkzee, E.; Fritsch-Stork, R.; Bultink, I.E.M.; Kamphuis, S. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes in a Cohort of Adults With Childhood-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019, 71, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, S.; Fraser, C. Hospice support and the transition to adult services and adulthood for young people with life-limiting conditions and their families: A qualitative study. Palliat. Med. 2014, 28, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, S.; Napier, S.; Adams, J.; Wham, C.; Jackson, D. An integrative review of the factors related to building age-friendly rural communities. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 2402–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K.A. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Adolescence: A Period Needing Special Attention. Available online: http://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/section2/page1/recognizing-adolescence.html (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention (accessed on 5 August 2016).

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: A modified e-Delphi study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 111, 49–59.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.; White, H.; Bath-Hextall, F.; Apostolo, J.; Salmond, S.; Kirkpatrick, P. Methodology for JBI mixed methods systematic reviews. Joanna Briggs Inst. Rev. Man. 2014, 1, 5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Uzuner, S.; Sahin, S.; Durcan, G.; Adrovic, A.; Barut, K.; Kilicoglu, A.G.; Bilgic, A.; Bahali, K.; Kasapcopur, O. The impact of peer victimization and psychological symptoms on quality of life in children and adolescents with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Rheumatol. 2017, 36, 1297–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckerman, N.; Sarracco, M. Listening to lupus patients and families: Fine tuning the assessment. Soc. Work Health Care 2012, 51, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, H.I.; Higgins, G.C.; Wiers, K.; Lapidus, S.K.; Olson, J.C.; Onel, K.; Punaro, M.; Ying, J.; Klein-Gitelman, M.S.; Seid, M. Health-related quality of life and its relationship to patient disease course in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Rheumatol. 2009, 36, 1536–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Case, S.; Sinnette, C.; Phillip, C.; Grosgogeat, C.; Costenbader, K.H.; Leatherwood, C.; Feldman, C.H.; Son, M.B. Patient experiences and strategies for coping with SLE: A qualitative study. Lupus 2021, 30, 1405–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceppas Resende, O.L.; Barbosa, M.T.; Simões, B.F.; Velasque, L.S. The representation of getting ill in adolescents with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rev. Bras. Reum. Engl. Ed. 2016, 56, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.M.; Graham, T.B.; Zhu, Y.; McPheeters, M.L. Depression and medication nonadherence in childhood-onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Lupus 2018, 27, 1532–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, C.; Cunningham, N.; Jones, L.T.; Ji, L.; Brunner, H.I.; Kashikar-Zuck, S. Fatigue and depression predict reduced health-related quality of life in childhood-onset lupus. Lupus 2018, 27, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harry, O.; Crosby, L.E.; Smith, A.W.; Favier, L.; Aljaberi, N.; Ting, T.V.; Huggins, J.L.; Modi, A.C. Self-management and adherence in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: What are we missing? Lupus 2019, 28, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández Zapata, L.J.; Alzate Vanegas, S.I.; Eraso, R.M.; Yepes Delgado, C.E. Lupus: “like a cancer but tinier”. Perceptions of systemic lupus erythematosus among adolescents nearing transition to adult care. Rev. Colomb. Reumatol. 2018, 25, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Lili, S.; Jing, W.; Yanyan, H.; Min, W.; Juan, X.; Hongmei, S. Appearance concern and depression in adolescent girls with systemic lupus erythematous. Clin. Rheumatol. 2012, 31, 1671–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.T.; Cunningham, N.; Kashikar-Zuck, S.; Brunner, H.I. Pain, Fatigue, and Psychological Impact on Health-Related Quality of Life in Childhood-Onset Lupus. Arthritis Care Res. 2016, 68, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohut, S.; Williams, T.S.; Jayanthikumar, J.; Landolt-Marticorena, C.; Lefebvre, A.; Silverman, E.; Levy, D.M. Depressive symptoms are prevalent in childhood-onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (cSLE). Lupus 2013, 22, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, L.N.; Baldino, M.E.; Kurra, V.; Puwar, D.; Llanos, A.; Peterson, M.G.E.; Hassett, A.L.; Lehman, T.J. Relationship between health-related quality of life, disease activity and disease damage in a prospective international multicenter cohort of childhood onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus patients. Lupus 2017, 26, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, L.N.; Peterson, M.G.; Hassett, A.; Baratelli, M.; Lehman, T.J. Impact of lupus on school attendance and performance. Lupus 2010, 19, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorthy, L.N.; Robbins, L.; Harrison, M.J.; Peterson, M.G.E.; Cox, N.; Onel, K.B.; Lehman, T.J.A. Quality of life in paediatric lupus. Lupus 2004, 13, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruperto, N.; Buratti, S.; Duarte-Salazar, C.; Pistorio, A.; Reiff, A.; Bernstein, B.; Maldonado-Velázquez, M.R.; Beristain-Manterola, R.; Maeno, N.; Takei, S.; et al. Health-related quality of life in juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus and its relationship to disease activity and damage. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 51, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.M.D.; Gorst, S.L.; Al-Abadi, E.; Hawley, D.P.; Leone, V.; Pilkington, C.; Ramanan, A.V.; Rangaraj, S.; Sridhar, A.; Beresford, M.W.; et al. “It is good to have a target in mind”: Qualitative views of patients and parents informing a treat to target clinical trial in JSLE. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 5630–5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.E.C.; Gao, X.; Ang, W.H.D.; Lau, Y. Medication adherence: A qualitative exploration of the experiences of adolescents with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 2717–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunnicliffe, D.J.; Singh-Grewal, D.; Chaitow, J.; MacKie, F.; Manolios, N.; Lin, M.W.; O’Neill, S.G.; Ralph, A.F.; Craig, J.C.; Tong, A. Lupus Means Sacrifices: Perspectives of Adolescents and Young Adults with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res. 2016, 68, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, A.; Tunnicliffe, D.J.; Thakkar, V.; Singh-Grewal, D.; O’Neill, S.; Craig, J.C.; Tong, A. Patients’ Perspectives and Experiences Living with Systemic Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. J. Rheumatol. 2016, 43, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawole, O.A.; Reed, M.V.; Harris, J.G.; Hersh, A.; Rodriguez, M.; Onel, K.; Lawson, E.; Rubinstein, T.; Ardalan, K.; Morgan, E.; et al. Engaging patients and parents to improve mental health intervention for youth with rheumatological disease. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 2021, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilter, M.C.; Hiraki, L.T.; Korczak, D.J. Depressive and anxiety symptom prevalence in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review. Lupus 2019, 28, 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, M.P.; Sage, A.M.; McKinnon, E.; Lee, S.J.; Tunbridge, D.; Larkins, N.G.; Murray, K.J. Childhood Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Presentation, management and long-term outcomes in an Australian cohort. Lupus 2022, 31, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, S.; Zhong, L.; Chen, C. Clinical and laboratory features, disease activity, and outcomes of juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus at diagnosis: A single-center study from southern China. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 4545–4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelrahman, N.; Beresford, M.W.; Leone, V. Challenges of achieving clinical remission in a national cohort of juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Lupus 2019, 28, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahar, D.N.; Nahar, P.N. A Children’s Tale: Unusual Presentation of Juvenile SLE. J. Rheum. Dis. Treat. 2022, 8, 96. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, A.; Maheshwari, M.V.; Khalid, N.; Patel, P.D.; Alghareeb, R. Diagnostic Delays and Psychosocial Outcomes of Childhood-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Cureus 2022, 14, e26244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felten, R.; Sagez, F.; Gavand, P.-E.; Martin, T.; Korganow, A.-S.; Sordet, C.; Javier, R.-M.; Soulas-Sprauel, P.; Rivière, M.; Scher, F.; et al. 10 most important contemporary challenges in the management of SLE. Lupus Sci. Med. 2019, 6, e000303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vollenhoven, R.F.; Mosca, M.; Bertsias, G.; Isenberg, D.; Kuhn, A.; Lerstrøm, K.; Aringer, M.; Bootsma, H.; Boumpas, D.; Bruce, I.N.; et al. Treat-to-target in systemic lupus erythematosus: Recommendations from an international task force. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathias, S.D.; Berry, P.; De Vries, J.; Askanase, A.; Pascoe, K.; Colwell, H.H.; Chang, D.J. Development of the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Steroid Questionnaire (SSQ): A novel patient-reported outcome tool to assess the impact of oral steroid treatment. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.L.; Foulkes, L.; Blakemore, S.J. Peer Influence in Adolescence: Public-Health Implications for COVID-19. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2020, 24, 585–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, A.; Weiss, P.; Morales, K.; Gerdes, M.; Gutstein, A.; Vickery, M.; Keren, R. Depression and anxiety and their association with healthcare utilization in pediatric lupus and mixed connective tissue disease patients: A cross-sectional study. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 2014, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, A.M.; Xie, M.; Mandell, D.S. Disparities in Psychiatric Diagnosis and Treatment for Youth with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Analysis of a National US Medicaid Sample. J. Rheumatol. 2016, 43, 1427–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.M.; Trupin, L.; Katz, P.; Yelin, E.; Lawson, E.F. Depression Risk in Young Adults With Juvenile- and Adult-Onset Lupus: Twelve Years of Followup. Arthritis Care Res. 2018, 70, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, M.S.; Bond, L.M.; Sawyer, S.M. Health risk screening in adolescents: Room for improvement in a tertiary inpatient setting. Med. J. Aust. 2005, 183, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Pinto, C.; García-Carrasco, M.; Campos-Rivera, S.; Munguía-Realpozo, P.; Etchegaray-Morales, I.; Ayón-Aguilar, J.; Alonso-García, N.E.; Méndez-Martínez, S. Medication adherence is influenced by resilience in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2021, 30, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, S.; Prothero, L.; D’Cruz, D.P. Physician-patient communication in rheumatology: A systematic review. Rheumatol. Int. 2018, 38, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Náfrádi, L.; Nakamoto, K.; Schulz, P.J. Is patient empowerment the key to promote adherence? A systematic review of the relationship between self-efficacy, health locus of control and medication adherence. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daleboudt, G.M.; Broadbent, E.; McQueen, F.; Kaptein, A.A. Intentional and unintentional treatment nonadherence in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63, 342–350. [Google Scholar]

- Emamikia, S.; Gentline, C.; Enman, Y.; Parodis, I. How Can We Enhance Adherence to Medications in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus? Results from a Qualitative Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalzi, L.V.; Hollenbeak, C.S.; Mascuilli, E.; Olsen, N. Improvement of medication adherence in adolescents and young adults with SLE using web-based education with and without a social media intervention, a pilot study. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 2018, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, J.; Wilson, R.; Gill, N.; Yamada, J.; Holt, J. A systematic review of internet-based self-management interventions for youth with health conditions. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009, 34, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, T.S.; Aranow, C.; Ross, G.S.; Barsdorf, A.; Imundo, L.F.; Eichenfield, A.H.; Kahn, P.J.; Diamond, B.; Levy, D.M. Neurocognitive impairment in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: Measurement issues in diagnosis. Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frittoli, R.B.; de Oliveira Peliçari, K.; Bellini, B.S.; Marini, R.; Fernandes, P.T.; Appenzeller, S. Association between academic performance and cognitive dysfunction in patients with juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Rev. Bras. Reum. Engl. Ed. 2016, 56, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, S.; Thomson, W.; Cresswell, K.; Starling, B.; McDonagh, J.E.; On behalf of the Barbara Ansell National Network for Adolescent Rheumatology. What do young people with rheumatic disease believe to be important to research about their condition? A UK-wide study. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 2017, 15, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saez, C.; Nassi, L.; Wright, T.; Makris, U.E.; Kramer, J.; Bermas, B.L.; Solow, E.B.; Bitencourt, N. Therapeutic recreation camps for youth with childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: Perceived psychosocial benefits. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 2022, 20, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, N.; Ciosek, A.; Kramer, J.; Solow, E.B.; Bermas, B.; Wright, T.; Nassi, L.; Makris, U. “You Just Have to Keep Going, You Can’t Give Up”: Coping mechanisms among young adults with lupus transferring to adult care. Lupus 2021, 30, 2221–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.T.; Vivolo, M.A.; Madden, P.B. Are diabetes camps effective? Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2016, 114, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shani, M.; Kraft, L.; Müller, M.; Boehnke, K. The potential benefits of camps for children and adolescents with celiac disease on social support, illness acceptance, and health-related quality of life. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 27, 1635–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faith, M.A.; Boone, D.M.; Kalin, J.A.; Healy, A.S.; Rawlins, J.; Mayes, S. Improvements in Psychosocial Outcomes Following a Summer Camp for Youth with Bleeding Disorders and Their Siblings. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 61, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushner Weinstein, S.; Berl, M.; Salpekar, J.; Johnson, J.; Pearl, P.; Conry, J.; Kolodgie, M.; Scully, A.; Gaillard, W.; Weinstein, S. The benefits of a camp designed for children with epilepsy: Evaluating adaptive behaviors over 3 years. Epilepsy Behav. 2007, 10, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, B.D.; Silva, B.; Figueiredo-Braga, M. Specific coping strategies in JSLE depression and anxiety–the untold story of brave soldiers. J. Immunol. 2021, 206, 66.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratsidou-Gertsi, P. Transition of the patient with Childhood-onset SLE. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 2016, 27, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alain, C.; Jeanette, A.; Kirsi, M.; Angela, E.; Laurent, A. Living with systemic lupus erythematosus in 2020: A European patient survey. Lupus Sci. Med. 2021, 8, e000469. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, K.; Park, J.; Joshi, A.V.; White, M.K. Patient Experience With Fatigue and Qualitative Interview-Based Evidence of Content Validation of The FACIT-Fatigue in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Rheumatol. Ther. 2021, 8, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo-Braga, M.; Cornaby, C.; Cortez, A.; Bernardes, M.; Terroso, G.; Figueiredo, M.; Mesquita, C.D.S.; Costa, L.; Poole, B.D. Depression and anxiety in systemic lupus erythematosus: The crosstalk between immunological, clinical, and psychosocial factors. Medicine 2018, 97, e11376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fu, T.; Yin, R.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, B. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Question: What Are the Experiences and Perspectives of Children and Young People Living with SLE/Lupus/Juvenile Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Population: Children and young people and youth Exposure: Living with SLE or lupus Outcomes/themes: Experiences/perceptions/perspectives | ||

| Search terms | ||

| Population | Exposure | Outcomes/themes |

| Child* | Lupus | Perception* |

| Young people | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | Perspective* |

| Young person | SLE | Experience* |

| Young adult* | Juvenile onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | View* |

| Youth* | cSLE | Opinion* |

| Teen* | cSLE | Attitude* |

| Adolescent* | Exposure | Reflection* |

| Pediatric | Lupus | Belief* |

| Pediatric | Qualitative | |

| Phenomenology* | ||

| Hermeneutic* | ||

| Citation | Country | Aim and Design | Sample | Data Collection | Findings | Strengths and/or Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [37] | USA | Aim: To gain insight into the emotional challenges posed by lupus. Qualitative study–narrative case study. | Family groups (n = 3) (only 1 family group met criteria), 18 years of age from 3 clinics. | Focus groups. | Body changes and uncertainty about progressions of disease most impactful. SLE impacts on daily life and relationships. Medication compliance is challenging. Feeling of responsibility for parents’ wellbeing. | Limitations include a small sample with only 1 of the three families meeting our age criteria and poorly reported methodology, and unconventional approach to reporting. Strengths include rich data from narratives. |

| [38] | USA | Aim: To estimate the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of children with childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) and compare it to that of normative cohorts; to assess the relationship of HRQOL with cSLE disease activity and damage; and to determine the effects of changes of disease activity on HRQOL. Quantitative study. | Patients with cSLE (n = 98) were followed every 3 months 60 Caucasian, 32 African American, 4 Asian, and 2 mixed-race patients (88 non-Hispanic, 10 Hispanic) from 7 centers. | Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core scale (PedsQL-GC), the Rheumatology Module (PedsQL-RM), the Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ), and the British Isles Lupus Activity Group Index (BILAG) was used to measure organ-system-specific disease activity. Physicians rated the course of cSLE between visits. | Active disease, the worsening of disease, and the presence of disease damage are all risk factors for poor HRQOL in cSLE. Children with cSLE have markedly lower CHQ-P50 scores than healthy children. Patients with cSLE have much lower scores on the PedsQL-GC. Control of disease is an important way to improve HRQOL in cSLE. Disease activity has a differential effect on HRQOL in cSLE, depending on the organ system involved. Lower HRQOL with the presence of Raynaud’s phenomenon. | Limitations include ratings of the change in cSLE patients’ health consistently from the patient were not collected. Thus, for the analysis, these ratings were simply combined. Most patients were adolescents, and findings, therefore, may not be applicable to younger children with cSLE. Numerous confounders of HRQOL, including socioeconomic status (SES), were not considered in the study. Strengths include a very thorough, rigorous study. |

| [39] | USA | Aim: To explore challenges that patients with SLE and cSLE face to identify modifiable influences and coping strategies in patient experiences. Qualitative study–phenomenology | Individuals (11–46 years) with SLE (n = 13), including cSLE (n = 7), mean age at diagnosis was 12 years, from 2 hospitals. | Focus groups. | Themes identified were challenges with SLE diagnosis and management; patient coping strategies, and modifiable factors of the SLE experience. Participants identified five primary challenges: diagnostic odyssey, public versus private face of SLE, SLE-related stresses, medication adherence, and transitioning from paediatric to adult care. Coping strategies and modifiable factors included social support, open communication about SLE, and strong patient–provider relationships. Several participants highlighted positive lessons learned through their experiences with SLE, including empathy, resilience, and self-care skills. | Strengths include the sample included individuals diagnosed with SLE at a variety of ages. Clear identification of data from the cSLE group. Findings section provides detailed analysis and is supported with appropriate quotes from participants. |

| [40] | Brazil | Aim: To analyze the social representations of chronic disease and its treatment from the perspective of adolescents and/or their caregivers. | Adolescents (n = 31), 11–21 years—4 boys and 27 girls from 1 hospital. | Free Association Words Test (FAWT), asked to associate five words to each one of the stimuli contained in the questions, “What comes to your mind when I say chronic disease?”; and then, “What comes to your mind when I say treatment of chronic disease?”. | Stimulus 1- (SLE) evoked sadness and pain (to a greater degree), medication, difficulty, learning, no cure, care, disease, limitation, faith, joy, and bad. Stimulus 2 (treatment)—medication and strength (to a greater degree), hope, improvement, consultation, discipline, joy, responsibility, health, needed, professional, help, care, cure, the word “no”, patience, bad, and affection. Differences noted between age and level of education treatment were seen positively (improvement, hope, help), with active participation of the patient (knowledge, obedience, schedule, medication). | Limitations include the use of an unconventional research methodology. Results differed between age groups and education, and this was acknowledged as a limitation. No collection of demographic characteristics which could influence social perception. No indication of disease severity and or medication use that would have influenced the response regarding disease. |

| [41] | USA | Aim: To estimate the prevalence of depression and medication non-adherence, describe demographic and disease characteristics associated with depression and medication non-adherence, and evaluate the correlation between depression and medication non-adherence and evaluate the association between depression and medication non-adherence in cSLE patients. Quantitative study. | cSLE (n = 51), 7–22 years, the subgroup analysis was limited to participants with ages between 12 to 18 years (n = 36) from 1 hospital. | The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) measured depression, the Medication Adherence Self-Report Inventory (MASRI) measured medication non-adherence, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI). | Positive depression screen in this study population of patients with cSLE was high (59%); the high rate of reported suicidal ideation- Nearly one-quarter (23%) of participants in this study who had a positive depression screen reported suicidal ideation at the time of the screen; patients who reported medication non-adherence in this study were more likely to have longer disease duration than those who reported medication adherence; prevalence of medication non-adherence in this study population of patients with cSLE was also notable with 20% of the participants reporting less than 80% adherence. | Limitations include a small sample from one hospital. The tools used to define the exposure and outcome (PHQ-9 and MASRI, respectively) each had inherent limitations. The study has demonstrated the feasibility of administering. depression and medication non-adherence screens within a clinical setting. |

| [42] | USA | Aim: To assess disease characteristics, fatigue, pain, psychological symptoms and HRQoL in patients with cSLE; to identify significant predictors of reduced HRQoL at follow-up and to use the most relevant predictors to create a risk stratification (High and Low Risk) for persistently poor HRQoL of adolescents with cSLE and describe the profile of disease and psychosocial characteristics for each of these groups. Quantitative study. | Children and adolescents with cSLE, 8 to 20 years, (n = 60) at first appointment; (n = 50) children at follow-up from 1 hospital; 84% female, with 23 (46%) African American and 23 (46%) Caucasian, 11–20 years, with mean age 16.2 SD +/−2.5 years. | The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Multi-dimensional Fatigue Scale (PedsQL-FS); the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI); the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS); Children’s Depression Inventory Version I (CDI-I); Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED); Pediatric Quality Of Life Inventory; Generic Core scale 4.0 (PedsQL-GC); PedsQL-RM; Functional Disability Inventory (FDI); the SLEDAI; measures of disease activity and patient-reported measures of health-related quality of life, pain, depressive symptoms, anxiety and disability were collected at each visit. | Using clinically relevant cut-offs for fatigue and depressive symptoms, patients were assigned to Low (n = 27) or High Risk (n = 23) groups. At visits 1 and 2, respectively, clinically relevant fatigue was present in 66% and 56% of patients. Clinically significant depressive symptoms in 26% and 24%; clinically significant anxiety in 34% and 28%. Poorer health-related quality of life at follow-up was significantly predicted by higher fatigue and depressive symptoms at the initial visit. | Limitations include that most participants were adolescents recruited from 1 hospital, which may limit generalizability of the findings for younger children, and correction for multiple comparisons in the data analysis was not undertaken. This was the first study to identify potentially modifiable predictors of impaired HRQoL in cSLE children/adolescents. |

| [43] | USA | Aim: To characterize factors influencing self-management behaviors and quality of life in adolescent and young adult (AYA) patients with childhood- onset systemic lupus erythematosus and to identify barriers and facilitators of treatment adherence via focus groups. Mixed Methods study. | Adolescents with cSLE ages 12–17 (n = 10) years and young adults with cSLE ages 18–24 years (n = 12) from 1 hospital or from the hospital’s cSLE active clinic registry. | Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Pediatric Short Form v1.0–Fatigue; the Pain Intensity Visual Analog Scale; SLEDAI; Focus groups. | Adolescent (n = 10) insurance cover–public cover (n = 6), private cover (n = 4). Adolescent PROMIS fatigue score (range) 57.5 (30.3–74.4). Adolescent Child Pain VAS mean (range) 3 (0–8). Adolescent number of medications (SD) 4.6 (2.5). Young adult (n = 12) insurance cover–public cover (n = 6), private cover (n = 6). Young adult PROMIS fatigue score (range) 57.4 (33.1–72.4). Young adult number of medications (SD) 3.5 (1.3). Themes included knowledge deficits about cSLE, symptoms limiting daily function, specifically mood and cognition/learning, barriers, facilitators of adherence, worry about the future, symptoms limiting daily functioning, pain/fatigue, self-care and management, impact on personal relationships, and health care provider communication and relationship. | Limitations include the sample being one of convenience and from 1 hospital and being predominantly Caucasian, which does not capture the ethnic groups with the highest morbidity. Strengths include using a design that used a quantitative and qualitative approach. |

| [44] | Colombia | Aim: To describe how adolescents nearing transition perceive lupus. Qualitative study—grounded theory. | Adolescents with SLE ages 15–18 years (n = 9) (7 females and 2 males), from 1 hospital. | Semi-structured interviews. | Varied interpretation and understanding about what lupus is/does to the body. Lupus and cancer seen as having similar consequences. Sense of guilt and self-blame re: diagnosis, blaming external factors for SLE such stress or food, invisible and visible forms of lupus, and taking responsibility and action for looking after self. Healthcare staff minimized symptoms- interactions and information sharing is key to learning and taking responsibility. Life with lupus is complicated and limiting- differences from others- but creates growth and sense of responsibility. | Limitations include a small sample size, and methodological underpinnings were poorly described. Strengths include the results being clearly presented with good use of quotes. |

| [45] | China | Aim: To examine the relationship between physical appearance concern and psychological distress in female adolescent patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Quantitative study. | Female adolescents with SLE (n = 84), mean 15.3 SD +/−1.4 years of age from 1 hospital. | Appearance concern was assessed by the physical appearance domain of the multi-dimensional Self Perception Profile for Children (SPPC). The SLEDAI was used to assess disease activity. Depression–the CDI covers negative mood, interpersonal difficulties, negative self-esteem, ineffectiveness, and inability to experience pleasure. | CDI: Nearly all patients showed increased depressive symptoms, as indicated by the mean scores on the CDI. The total mean CDI was 18.5 ± 4.3, indicating that these patients were experiencing depressive symptoms. Furthermore, a total of 32 (38.1 %) patients had CDI larger than 19 points. Among the CDI subscales, negative mood, negative self-esteem, and anhedonia contributed to the total scores mostly. Physical Appearance: Regarding the concern about appearance, 77 (91.7 %) patients with SLE reported that they felt unattractive due to the disease, according to the questions from the SPPC. Among the SLE patients, the SPPC physical appearance score was 13 ± 2.8, indicating that the SLE adoles cents believe their appearances were severely impaired. Appearance concern was highly correlated with depression (r 0.758, p 0.001). Subsequently, age was moderately correlated with depression (r 0.468, p 0.001). Other variables, such as the number of admissions and disease duration, were partially correlated with depression. | Limitations include the use of a generic measure for physical appearance evaluation and is less robust than a more comprehensive one and less effective than a SLE-specific evaluation tool. The self-administered evaluation of depression through the CDI could have failed to capture the whole depressive disorders. The authors failed to evaluate appearance concerns and psychological conditions of the adolescents before the SLE onset because the patients who received these questionnaires had been treated with an average of 15.8 months, and male adolescents were excluded. |

| [46] | USA | Aim: To evaluate pain, fatigue, and psychological functioning of childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients and examine how these factors impact health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Quantitative study. | Children and adolescents with cSLE (n = 60), 8–20 years, mean 16.1 SD +/−2.5, years of age from 1 hospital. | The visual analog scale (VAS) of pain intensity (0–10), the Adolescent Sleep Wake Scale (ASWS), FDI, the PedsQL–FS, Pain Coping Questionnaire (PCQ), the PCS, SLEDAI, the CDI-I, the SCARED questionnaire, and the PedsQL–GC scale and PedsQL–RM module. | The PedsQL-GC, -RM, and -FS summary scores were significantly lower in the childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus population than in reference populations of healthy children, and those with arthritis. Although most of the childhood- onset SLE patients reported no more than minimal functional disability, 18% (11 of 60) reported moderate to high functional disability (FDI > 13). Of the childhood-onset SLE patients in the study sample, 65% (39 of 60) reported to have fatigue on the clinician-administered checklist, with 40% (24 of 60) reporting clinically relevant pain (pain-VAS of 3). Further, 30% (18 of 60) of the study participants reported clinically important depressive symptoms (CDI-I of 12), 37% (22 of 60) reported clinically relevant anxiety, and 22% (13 of 60) reported a high level of pain catastrophizing. On average, fatigue, anxiety, and depression were not found to be significantly greater among patients on steroid therapy compared to those not requiring steroid therapy (fatigue [PedsQL-FS] score: 55.0 versus 60.5, anxiety [SCARED] score: 24.1 versus 20.7, and depression [CDI-I] score: 9.6 versus 9.8; all p values were not significant). The scores of the fatigue (PedsQL-FS), anxiety (SCARED), and depressed mood (CDI-I) measures were all highly and sig nificantly correlated with HRQOL (PedsQL-GC and -RM). The BPI and pain-VAS were highly correlated and also featured similar correlations to the remaining variables. only. HRQOL measured by PedsQL-GC was significantly impacted by fatigue and pain (R2 5 0.75, p, 0.001), with fatigue predicting 42% and pain predicting 33% of the model variance, but pain coping, anxiety, pain catastrophizing, and depression did not significantly predict PedsQL-GC scores. The PedsQL-RM was significantly impacted by pain, fatigue, and anxiety (R2 5 0.71, p, 0.001), with pain predicting 33%, fatigue predicting 25%, and anxiety predicting 7% of model variance, but pain coping, pain catastrophizing, and depression did not significantly predict PedsQL-RM scores. Both support the notion that pain, fatigue, and to a lesser extent anxiety account for significantly diminished HRQOL observed in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus patients. | Limitations include the majority of the patients being teenagers, the sample size being small, and the design being cross-sectional. Strengths include the patients studied were well-phenotyped and are representative of those followed at the hospital. |

| [47] | USA | Aim: To assess emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents with SLE during the remission of disease activity. Quantitative study. | Cohort 1: children and adolescents with cSLE disease (n = 38), 10–18 years old from 1 clinic. Cohort 2: young adults with cSLE, (n = 16), 18–24 years from 1 clinic. | Cohort 1: CDI, Intelligence test, Pediatric Quality of Life Index, SLEDAI, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics Damage Index (SDI). Cohort 2: Intelligence test, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), Health Survey, SLEDAI, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics Damage Index (SDI). | In cohort 1 10 patients had elevated depression scores (26%), and three (8%) subjects had clinically significant depression scores (T score 65). No subject endorsed suicidality. In cohort 2, seven (44%) of the young adults had elevated depression scores (10), with two (12.5%) subjects scoring in the moderate to severe depressive symptoms range (>19). Similarly, no subject endorsed suicidality. Symptoms receiving the highest mean ratings by cohort one included fatigue, school problems, indecisiveness, despair, and sleep disturbances. The most severe individual depressive symptoms endorsed by cohort two included sleep disturbances, loss of energy, fatigue, changes in appetite, and indecisiveness. | Limitations include a small sample size, allowing for hypothesis generation and potentially limiting our ability to detect differences even if they were present and data collection was cross-sectional. |

| [48] | USA | Aim: To determine the relationship between HRQOL, disease activity, and damage in a large prospective international cohort of cSLE. Quantitative study. | Children and adolescents with SLE (n = 456), (384 females) from 39 centres across four continents (North America, South America, Europe, Asia). | SMILEY, PedsQL–GC scale and PedsQL–RM module, SLEDAI, Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA), Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index (SDI)–data collected across 6 collection points V1-V6). | The highest domain scores were: Social and Physical (PedsQL Generic), Daily Activities (PedsQL Rheumatology), and Social (SMILEY). Lowest domain scores were: Emotional (PedsQL Generic), Worry (PedsQL Rheumatology), Effect on Self, and Burden of SLE (SMILEY). Patients with higher disease activity (SLEDAI > 12, PGA > 2), higher damage (SDI > 2), and current/past cyclophosphamide and/or rituximab use had lower SMILEY Limitation domain scores at visits V1 (p < 0.05 for all values for SMILEY). Patients with higher disease duration did not have lower SMILEY Limitation domain scores except at V3. PGA, SLEDAI and SDI, and SMILEY scores did not differ between the two genders; however, child SMILEY scores were lower in girls. | Limitations include missed information on children who were excluded or the reason for attrition. The strengths include a large sample across four continents and the use of validated tools. |

| [49] | USA | Aim: to explore children’s (and adolescents’) perception of the impact of SLE on school, the relationship between child and parent reports on school-related issues, and the relationship between health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and school-related issues. Quantitative study. | Children and adolescents with SLE (n = 41) (73% girls), 9–18 years, mean age was 15 SD +/−3 years from two centers. | SLE-specific HRQOL scale, SLEDAI, Simple Measure of Impact of Lupus Erythematosus in Youngsters (SMILEY), PedsQL–GC scale, and PedsQL–RM module. | Mean school domain scores for children of the PedsQLTM generic report were lower compared with total and subscale scores. Patients reported difficulty with schoolwork, had problems with memory and concentration, and were sad about the effect of SLE on schoolwork and attendance. Eighty-three percent of patients felt that they would have done better in school if they did not have SLE. Moderate correlations (r = 0.3–0.4) were found between SMILEY_ total score and the following items: satisfaction with school performance, interest in schoolwork, remembering what was learned, and concentrating in class. Patients on intravenous chemotherapeutic medications missed more school days (p < 0.05) compared with patients on oral medications. | Limitations include potential recall bias among patients and the need for a larger sample so children’s responses could be stratified by age. The strengths include data collected across two centers and the use of validated tools. |

| [50] | USA | Aim: To identify domains that are critical in determining QOL in children with SLE. Qualitative study–grounded theory. | Children with SLE (n = 38), (30 females) 6–20 years from 1 center. | Interviews and written responses. | Limitations of SLE are physical, social, and psychological. Impact on daily life, on social and family relationships. Impact on self- related to medication side effects and disease effects. Sadness about diagnosis-rationalizing and normalizing as coping mechanisms. Stress and anxiety about the future. | Limitations include a small sample, poorly described methodology, and data were collected from 1 center. |

| [51] | Italy | Aim: To assess the health-related quality of life (HRQL) of patients with juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (CSLE) and its relationship with disease activity and accumulated damage. Quantitative study. | Children and adolescents with juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (CSLE), (n= 297), (252 female), mean 16.2 SD +/−4.9 years of age from 8 hospitals and groups across four countries (Europe, the US, Mexico, and Japan). | CHQ, SLEDAI, SDI | Most impaired CHQ subscales were global health, general health perceptions, and parent-impact emotional. Compared with healthy children, CSLE patients had lower values in all subscales of the CHQ. The progressive decline of HRQL with increasing disease activity and accumulated damage effect more pronounced in both instances on the physical than in the psychosocial health domain. Greater impairment of HRQL occurred in patients with active disease in the central nervous, renal, and musculoskeletal systems. Active nephritis and seizure most significantly affected family life (PE, PT, and FA). Lupus headache was the only disease manifestation that impaired Mental health. Pleurisy and fever had a more significant impact, respectively, on BP and CH. Marked reduction of self-esteem associated with renal disease. HRQL abnormalities were more associated with clinical features than with laboratory abnormalities. | Limitations include the use of a cross-sectional design where it is difficult to determine a causal relationship since there is doubt about the timing of when a child is in remission or in the middle of an exacerbation of SLE. |

| [52] | United Kingdom | Aim: To explore in depth the views of CSLE patients and parents on potential treatment targets (e.g., LLDAS), outcome measures (e.g., HRQOL and fatigue measures), and study designs being considered by TARGET LUPUS in light of their previous treatment and care. Qualitative study. | Children and adolescents with CSLE, (n= 12), (10 female), 9–18 years, mean age 14 years from eight centers. | Semi-structured interviews. | Variation in treatment response. Symptoms that represented lupus low disease activity state (LLAS) were variable and different from adults. Intolerable visible signs of lupus- steroids are undesirable-symptoms–medicine side effects- fatigue is a significant symptom—wanted to minimize disruption from CSLE in all aspects of the patient’s life and preferred treatment goals to include corticosteroid dose reduction, HRQOL, and fatigue in addition to the targeting of disease activity. | Strengths include the methods section being clear and concise. Good inclusion of quotes from participants and data collected from eight centers. |

| [53] | Singapore | Aim: To explore experiences in medication adherence among adolescents with SLE. Qualitative study. | Adolescents with SLE (n = 14), 11–19 years, mean age 15.4 SD 2.06 years from one hospital. | Semi-structured interviews. | Adjusting and creating a new normal that included medicines- contending with the side effects of medications was challenging- understanding the ‘why’ encouraged adherence. Participants felt that viewing a graphical model of their blood test results over their disease courses provided clearer representations of how medications or the lack of such influenced their conditions over time. Avoiding hospitalization and being sick were also goals that the participants strived toward, further increasing their medication-taking motivations. Participants resented doctors’ lack of transparency when they explained the medications’ side effects. Taking steroids was of the greatest concern because these medications made them gain weight. | Limitations include inconsistencies with reporting participant numbers. Strengths include a methodologically sound study that was well described. |

| [54] | Australia | Aim: To describe the experiences, perspectives, and health care needs of adolescents and young adults diagnosed with SLE prior to age 18 years. Qualitative study–grounded theory. | Adolescents and young adults (n = 26), (24 female), 14–26 years, mean age 18 years from five hospitals. | Focus groups and interviews. | Being treated differently, reluctance to disclose. Poor self-image felt different from peers. Physical manifestations of disease and medication side effects impacted negatively on the image of self. Isolation and stigma. Symptoms impacted future aspirations (jobs, parenthood, study). Lack of age-appropriate information- uncertainty about the future- Knowledge of SLE was mixed. Desire for autonomy and developing self-reliance. Positive side to SLE: greater confidence and strength of character. Successful management relied on family and friends. Relationship with clinicians- important to have trusted relationships- some talked about being ‘judged’. | Limitations include some methodological confusion in the description of the analysis approach undertaken. |

| [36] | Turkey | Aim: To assess the peer victimization, depression, anxiety, self-esteem, and QOL levels and compare them with those of the control group; to evaluate the association between QOL, psychological symptoms, and peer victimization; and to examine the determinants of QOL in these patients. Quantitative study. | Children (n = 9) and adolescents (n = 32) with SLE, 32 females), 9–18 years, mean 14.7 SD +/−2.6 from 1 hospital. | SLEDAI, Peer victimization scale (PVS), CDI, State-trait anxiety inventories for children (STAIc), PedsQL, Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale (RSS). | Peer victimization, self-esteem, depression, anxiety, and QOL levels of the patients with SLE were not worsened than those of the control group. Peer victimization and trait anxiety levels have roles in determining the QOL impairment of children and adolescents with SLE. The difference in levels of peer victimization between the patients and controls was not statistically significant. SLE patients with lower disease activity may have lower depression and anxiety levels compared with those with higher disease activity. | Limitations include data collection being from 1 hospital, a structured psychiatric interview was not performed, and a disease-specific questionnaire for measuring QOL was not used. |

| Illustrative Quotation Reflecting Each Theme | ||

|---|---|---|

| Participants Quotations and/or Authors Explanations | Contributing References | |

| Challenging Symptoms Disruption to life and altered self | I can’t go outside to play with my own friends. I lost my old friends. I can’t do the stuff that kids of my age do. Cause sometimes I feel tired and boring. Cause when I got lupus, I change cause now I can’t do the stuff I could do before. Everything in my life changed [44] Feeling isolated, even though you are with the people you care about, you just still feel isolated, because you can’t do what they are doing [50] I don’t really tell all of my friends. I was actually ashamed to tell anyone at first when I was diagnosed [39] | [37,39,43,44,45,50,52,54] |

| Severity | I believe that there are several types of lupus, but mine is like… I don’t know… tougher [44] | [38,39,50,52,54] |

| Depression and anxiety | The prevalence of a positive depression screen in this study population of patients with cSLE was high (59%) * [41] Nearly one-quarter (23%) of participants in this study who had a positive depression screen reported suicidal ideation at the time of the screen * [41] | [41,45,46,47,48] |

| Fatigue | Fatigue is the most difficult part of having lupus. Lupus is an evil disease that makes you sleep a lot. [43] The fatigue I feel isn’t like the flu, it’s like I’ve been knocked over by a bus [37] Fatigue, joint symptoms, and headaches had a markedly detrimental effect on the HRQOL of children with cSLE * [52] | [37,38,41,43,46,52] |

| Medicines and Side Effects Dreaded steroids | It was really hard getting to school. I was on prednisone and got pretty fat, so I was getting bullied a lot. It was hard [54] It was just so defeating. No matter how hard I try now, I can’t take off weight and I have this fat face. Who’s going to want to date me? [37] I just wanted to come off them. Even when I was only on half a tablet, I didn’t feel happy with being on them [52] | [39,44,52,53,54] |

| Conflicting feelings | All the medicine I have to take, I don’t see results right then and there... What’s the purpose of taking it? I’m going to feel the same regardless. (Young adult) [43] …Having lupus doesn’t make me feel happy. But it doesn’t make me feel sad. I wouldn’t say how lonely do you feel because of lupus. Like, I’m not sad, I’m not lonely, but I’m not happy [52] | [40,43,49,50,52,53] |

| Medication adherence | So sometimes if I’m busy one day and I just forget. If I forget one dose, I just start forgetting it for a couple of days [39] The prevalence of medication non-adherence in this study population of patients with cSLE was also notable with 20% of the participants reporting less than 80% adherence with SLE medications * [41] | [37,39,41,43,44,52,53,54] |

| Complicated Life School, sports and social activities | I’d like to go back to school and pursue my education, but I just don’t know if it’s realistic. I keep trying to get it under control, but I don’t know if there’s such a thing [37] Being sick makes others impose limitations on me [44] I couldn’t be like the rest of them [44] | [37,44,49,50] |

| Giving things up | You can’t be a kid in the moment, you have to think weeks and months...I know if I do this, I can’t do this the next night. And a lot of kids don’t have to do that [43] Having lupus prevents you from doing things you like a lot [44] For me lupus means sacrifices. I can’t actually do what I want to [54] | [43,44,50,54] |

| Quality of life | Living with lupus is complicated because of the medicines and the medical appointments [44] Patients with jSLE have poorer HRQL as compared with healthy controls in both physical and psychosocial domains, with physical health being more affected [51] | [36,38,42,44,46,48,50,51] |

| Lack of understanding | My teacher decided to tell all of them I had lupus, and they thought they could catch it. So, they wiped the seats off with cleaning wipes... trying not to catch the lupus [43] I was told I had lupus and my mother… well she didn’t want to tell me anything [44] When I was younger, I could have had someone explain it to me… that it wasn’t something that wasn’t going to go away [54] | [39,43,44,50,54] |

| Ways of Coping Family and friends | This is a great comfort to me. Talking to other SLE patients has been so helpful. Only they know what it’s like to have the disease, to feel too tired to get out of bed, to feel pain in your joints [37] What helped me the most, I had a really big group of friends, and they didn’t really care what I looked like [54] | [37,39,40,53,54] |

| Relationships with health providers | It’s really all about the connection with your doctor… I think it’s just the relationship that you have with your doctor [39] I will still just take medicine cos I mean it’s prescribed by the doctor…I trust that my doctor would know some of the side effects…make informed decision on dosage [54] | [37,39,40,50,52,53,54] |

| Maintaining positivity | I try to be optimistic and hope that if I make plans, I’ll be healthy enough when that day comes. If I’m not, I hope others will understand [37] Having lupus helps you in many ways: makes you more responsible [44] | [37,44,54] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blamires, J.; Foster, M.; Napier, S.; Dickinson, A. Experiences and Perspectives of Children and Young People Living with Childhood-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus—An Integrative Review. Children 2023, 10, 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061006

Blamires J, Foster M, Napier S, Dickinson A. Experiences and Perspectives of Children and Young People Living with Childhood-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus—An Integrative Review. Children. 2023; 10(6):1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061006

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlamires, Julie, Mandie Foster, Sara Napier, and Annette Dickinson. 2023. "Experiences and Perspectives of Children and Young People Living with Childhood-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus—An Integrative Review" Children 10, no. 6: 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061006

APA StyleBlamires, J., Foster, M., Napier, S., & Dickinson, A. (2023). Experiences and Perspectives of Children and Young People Living with Childhood-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus—An Integrative Review. Children, 10(6), 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061006